1. Introduction

The basic premise of sustainable employment is to pursue the sustainability of human survival and development ability, which aims at promoting sustainable and effective employment creation of the whole society, continuously improving the quality of labor force and employment, and fully satisfying the employment development of workers. The fundamental goal is to achieve the effective allocation of labor elements in the sustainable development system. With the development of international trade and investment, the allocation of production factors on a global scale will inevitably have an important impact on employment in various countries. China is a country with a large population, and employment has always been an important issue in Chinese social and economic development. From the perspective of the development process of international investment, a big foreign direct investment (FDI) absorber will gradually become a big source of foreign investment. China is a big country that has absorbed FDI for a long time. With the acceleration of China’s opening up process, more and more Chinese capital has entered the international market, and the proportion of China’s outward foreign direct investment (OFDI) in global foreign investment market is also growing. According to data in the 〈〈Statistical communique of China’s OFDI in 2017〉〉, China’s OFDI in 2017 was $158.29 billion, which ranked third in the world behind the United States ($342.27 billion) and Japan ($160.45 billion). The influence of China’s OFDI in global FDI (foreign direct investment) is constantly expanding.

Existing literature studies have focused on the impact of OFDI on home employment in developed countries such as Europe and the United States. However, there is not only a lack of relevant research on China, but also a controversy. The effect of OFDI on home country employment is influenced by many factors, among which regional marketization plays an extremely important role. Since China itself is the largest developing country, with China’s opening to the outside world, there are also significant differences in the development of regional marketization. In some areas of China, the process of marketization is faster, while in others, the process of marketization is slow.

However, there existing obvious difference not only in the investment scale in various areas of China, but also in regional marketization, according to Wang Xiaolu ’s [

1] reports. Then, with the gradual deepening of opening-up and market-oriented reform, what impact will China’s OFDI have on domestic sustainable employment? Is it a facilitation effect or a substitution effect? Are there significant differences in the effects of FDI on domestic sustainable employment in different regions of the marketization process? How can local governments further develop OFDI to expand the domestic employment scale and optimize the employment structure so as to realize the optimal allocation of domestic resources? Thinking about these issues is an important topic in current academic research and policy practice, which has certain theoretical and practical significance. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to theoretically analyze the transmission channels of market-oriented factors in the effect of OFDI on employment in home countries, and to empirically analyze the significant differences in the impact of OFDI on sustainable employment in different regions with different market-oriented processes. Finally, on the basis of theoretical and empirical analysis, the paper will find out the corresponding countermeasures for local governments to make use of OFDI to expand the scale of domestic employment, optimize the employment structure, and realize the optimal allocation of domestic resources. The research process and conclusions of this paper are not only suitable for China, but also valuable for other developing countries, such as India, Brazil, and South Africa, which have the same marketization process as China.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Researches on the Effect of OFDI on Employment in Home Country

Early research on the effect of OFDI on employment in the mother country mainly focused on the debate of the employment substitution effect or the employment supplement effect. Jasay [

2] supported the employment substitution effect; he thought that foreign direct investment would replace part of domestic investment and consumption in the home country of capital under the condition of limited resources if the money outflow did not decrease with the growth of exports or import, because the motherland employment can produce negative effects or the substitution effect. Following Jasay’s research, Hawkins [

3] put forward an opinion on the basis of employment in effect (complementary effects) theory that foreign investment will supplement or promote domestic investment and consumption. This is particularly so in the case of defensive investment, in which the intention of enterprise investment abroad is to develop domestic resources or—due to tariff barriers—hinder its export transverse to foreign investment. Then, this type of investment—which is often produced upon the homeland capital equipment—can increase foreign subsidiaries, intermediate products, or auxiliary products demand, so as to produce positive effects on domestic employment. Hamill [

4] believed that the employment effect of FDI in a multinational company’s home country is uncertain and unstable due to the different effects of its adoption of standalone strategies, simplex integration strategies, and complex integration strategies on its employment in its home country. Campbell [

5] and UNCTAD [

6] argued that the potential effects of transnational corporations’ FDI on employment in their home countries included direct positive and negative effects as well as indirect positive and negative effects.

In recent years, scholars’ studies on OFDI’s employment effect in China generally believe that the differences in investment motivation or type, host country type, factor intensity, industry distribution of OFDI, and income level between host country and investment country should be taken into account. Braconier and Ekholm [

7] believed that vertical OFDI locates the labor-intensive production stage in countries with low labor cost, while locating the capital and technology-intensive production stages in high-income countries. Vertical OFDI will promote the improvement of employment levels in home countries. However, in the current period, the migration of domestic production capital abroad may have a substitution effect on employment in home countries. Horizontal OFDI is where multinational companies take full advantage of their monopoly advantage to arrange production in many countries in order to get more opportunities for overseas markets and economies of scale effects. If the production of goods is tradable, the substitution effect of employment may occur between parent companies and overseas branches because domestic exports will be replaced by foreign production. If the production of goods is non-tradable, such a substitution effect of employment could not be produced.

Blomstrom et al. [

8] studied the OFDI of the American manufacturing industry and showed that American multinational companies arranged labor-intensive production in subsidiaries of developing countries, which had a substitution effect or negative effect on domestic employment. The research on Sweden’s manufacturing OFDI suggests that Sweden has more overseas capital-intensive production arrangements, especially in the high-income countries. A complementary effect or positive effect on domestic employment may occur because the domestic parent company provides necessary ancillary services for foreign subsidiary production, in cases where the parent company maintains stable production. Other research results show that OFDI in countries with different factor endowments (income levels) has different substitution effects on employment in the mother country. In other words, investment in low-income countries is more likely to produce substitution effects on employment in the mother country than investment in high-income countries. For example, Brainard and Riker’s [

9] study on the manufacturing industry in the United States showed that the establishment of subsidiaries in low-wage countries by multinational companies would have a strong substitution effect on domestic employment in the United States, while the establishment of subsidiaries in other income-level countries would only have a moderate substitution effect on domestic employment in the United States.

Due to the late start of China’s outward FDI, some domestic scholars, such as Luo Liangwen [

10] have made a qualitative analysis of the domestic employment effect of China’s OFDI on the basis of foreign theories. Basically, they believe that China’s outward FDI is at the initial stage, the degree of international integration is not high, and many investments are defensive. The current-period employment stimulation effect of investment is obviously greater than the employment substitution effect. For example, Jiang Yapeng and Wang Fei [

11] used the time series data from 1981 to 2010 to perform a cointegration analysis, and concluded that the employment effect of China’s home country of OFDI was generally positive. Zhang Jiangang et al. [

12] used the panel data of 30 provinces (cities and districts) from 2003 to 2010, and the Sys-GMM method to empirically examine the impact of China’s OFDI on domestic employment. Regional differences show that nationwide, OFDI has a greater effect on employment creation than substitution. The effect of OFDI on employment creation in the eastern region is greater than that of substitution, while the effect of FDI in the western region is mainly substitution due to its late start. Zhang Haibo and Peng Xinmin [

13] empirically studied the employment effect of OFDI in different regions with different levels of economic development and education in China by using the panel data of 29 provinces (cities and districts) from 2003 to 2010. The results show that in general, OFDI has an alternative effect on domestic employment, while in high-income areas, OFDI has an alternative effect on domestic employment. OFDI in middle-income areas has an alternative effect on domestic employment. In low-income areas, OFDI has no significant effect on domestic employment. In high-education areas, OFDI has a supplementary effect on domestic employment, while in middle-education and low-education areas, OFDI has an alternative effect on domestic employment.

2.2. Research on Marketization Process and China’s Economic Development

At present, relevant research studies on the marketization process and China’s economic development mainly cover three aspects. (1) The first is the marketization process index. Fan et al., [

14], Zhao Wenjun, and Yu Jinping [

15] traced the relative process of China’s regional marketization and comprehensively evaluated the progress of marketization from aspects of the relationship between the government and the market, the development of the product market, the factor market, and the organizational and legal system environment in the market. (2) The second is marketization process and economic growth. By referring to Wurgler’s capital allocation efficiency estimation model, Zhang Haiyang [

16] made an empirical analysis of the impact of China’s marketization process on capital allocation efficiency. Zhang Haibo and Peng Xinmin quantitatively investigated the contribution of marketization reform to total factor productivity and economic growth by using the relative index of the marketization process in various provinces of China.

Jiang Yapeng and Wang Fei empirically analyzed the relationship between the marketization process and the mode of economic growth based on the panel data of provinces in China. Most scholars believe that China’s market-oriented reform has improved its total factor productivity and thus economic growth by improving the incentive mechanisms, enhancing product market competition, improving the factor markets, promoting technological progress, and promoting the development of the non-state economy. (3) The third aspect involves the marketization process, FDI inflow or trade export, and domestic technological innovation. Scholars such as Jiang dianchun and Zhang yu [

17] introduced the marketization process into the empirical model and applied different empirical methods to reveal the impact of institutional changes on the process of China’s economic transition on domestic technological innovation brought by FDI inflow or trade export.

The above literatures laid a premise and foundation for an in-depth study of the domestic employment effect of OFDI in the marketization process of countries in transition. However, it is a pity that few scholars have paid attention to the impact of institutional factors on the employment rate within the home country of OFDI. As a country in transition, China has a different institutional environment from those of developed countries. The impact of institutional factors alongside the effect that OFDI has on employment within its home country cannot be ignored. The perfect market institutional environment is related to the specific relationship between OFDI and employment in its home country. However, it is worth noting that few scholars have paid attention to the impact of a country’s institutional factors on the employment effect in the home country of OFDI. As a large developing country, China has 31 provincial-level administrative regions of considerable scale.

Although the macro-environment and political system are basically the same, there is an obvious imbalance in the marketization degree of each province and urban area. On the one hand, the expansion of OFDI in developing countries is conducive to accelerating the domestic marketization process and improving the total factor productivity and the allocation efficiency of resources so as to increase domestic employment and output. On the other hand, a perfect market institutional environment is a necessary prerequisite for the effective performance of OFDI’s domestic employment effect. For countries or regions with different degrees of marketization, the effects that OFDI has on employment in each home country are quite different.

Therefore, based on endogenous economic growth theory and from the perspective of macro supply, this paper first clarifies the impact mechanism of OFDI on domestic employment in the marketization process of countries in transition, especially the relationship between the marketization process, OFDI development, and OFDI’s domestic employment effect. Secondly, by referring to the analysis methods of Greenaway et al. [

18] and Milner et al. [

19], an analysis framework of OFDI’s impact on domestic employment was constructed from the perspective of the C–D production function, and the overall effect of China’s OFDI on domestic employment was empirically tested. In addition, the mean value of the marketization relative index of Fan Gang and Wang Xiaolu et al. [

20] was used to classify 31 provinces and cities in China so as to further empirically test the difference of OFDI’s domestic employment effect in different regions of China’s marketization process. It is expected to bring some enlightenment to the formulation and implementation of relevant policies.

3. Mechanism, Model, and Data

3.1. The Transmission Mechanism of Marketization Process and OFDI Domestic Employment Effect

The source of economic growth comes from the growth of factor input and the improvement of total factor productivity (TFP). Based on the theory of endogenous economic growth [

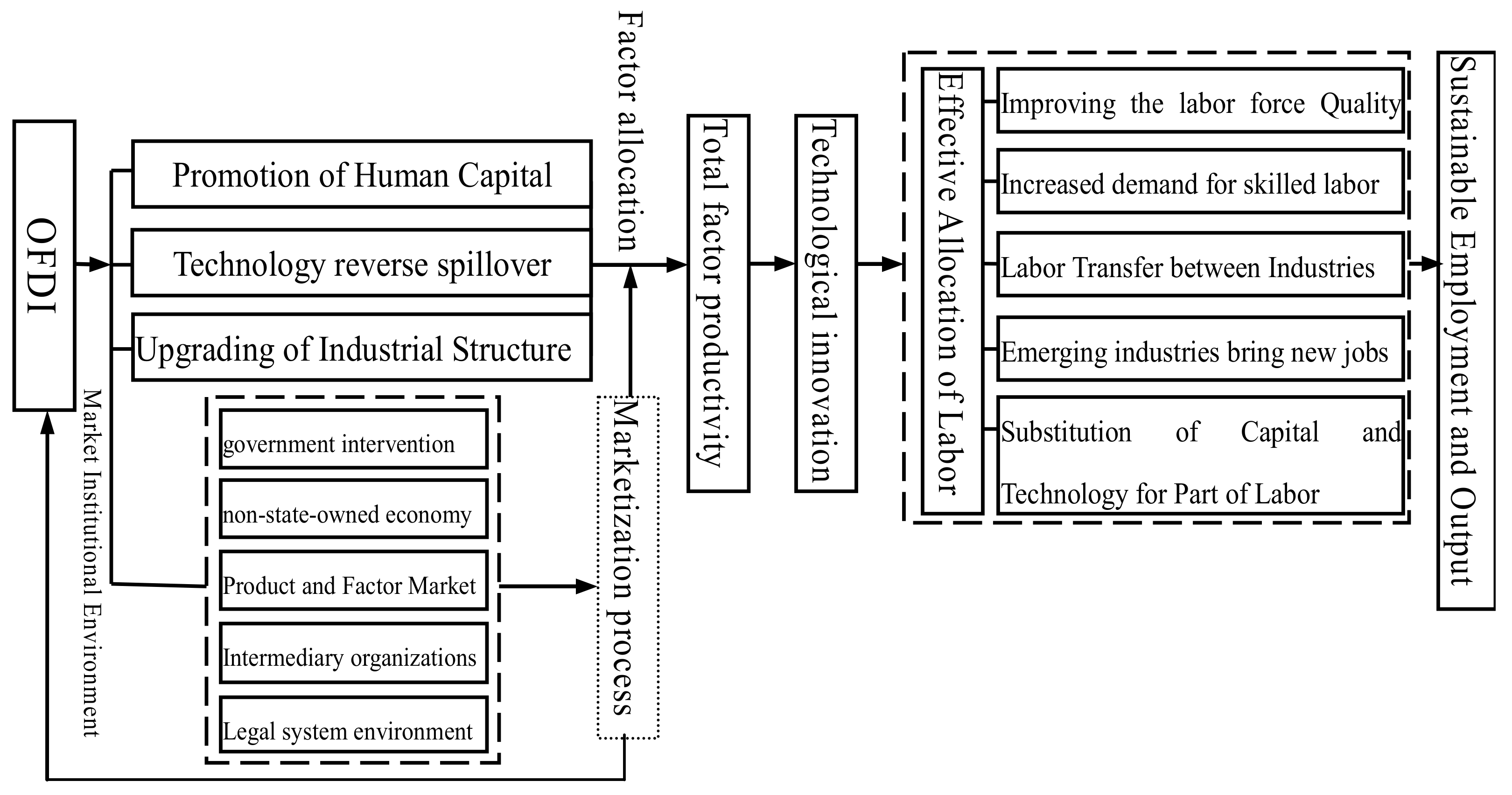

21], this article argues that from the perspective of macro supply, the impact of OFDI on the employment and output of the mother country is not only reflected in the impact on the input quantity of factors (labor and capital, etc.), but more importantly on the total factor productivity, technological progress and innovation, and then on the efficiency of resource allocation. Foreign direct investment in developing countries can accelerate the home country’s total factor productivity through (i) increasing human capital, (ii) the international technology reverse spillover effect, (iii) upgrading the industrial structure, and (iv) the role of accelerated marketization channels to promote technological progress and improve the allocation efficiency of labor resources and ultimately affect domestic employment and output, as shown in

Figure 1.

(1) Channel of human capital promotion. At present, in the process of economic globalization, developing countries need lots of high-level professional talents that master international laws and regulations with an international perspective in their foreign direct investment cooperation, which encouraged developing countries and enterprises to increase their human capital investment, develop domestic education and vocational skills training, and cultivate international professional and technical personnel so as to meet the human capital needs of multinational companies. The improvement of human capital means improving the quality of the labor force, which further improves the production efficiency or labor productivity of the whole society and promotes the increase of employment and output. At the same time, the improvement of labor skills also makes their employability continuously enhanced, and the industrial structure and employment structure of the whole society are optimized.

(2) Channel of international technology reverse spillover. OFDI, especially technology-seeking OFDI, is an important way for developing countries to obtain international technology reverse spillover. The OFDI enterprises of developing countries obtain foreign advanced research and development (R&D) resources and achievement by the use of a technology cluster absorption mechanism, an overseas competition mechanism, an R&D resources-sharing mechanism, and a two-way communication of technology mechanism. Then, the foreign advanced R&D resources spread to other relevant domestic enterprises and finally promote the domestic technology level of ascension, which affects the domestic employment and output in developing countries [

22]. In addition, since the technological progress and labor productivity of various industries and departments are unbalanced, the labor force will transfer among different industries and departments, and the employment trend of various industries and departments will change accordingly. It has been proved practically that employment in the primary industries was in decline, while those in the secondary and tertiary industries were in the upward trend since 1978’s reform and opening up.

(3) Channel of industrial structure’s upgrading. Under open economic conditions, the extraversion of a country’s industrial structure is increasingly obvious and evolves with the international flow of goods and capital. Developing countries’ OFDI cannot only expand the international market and participate in international competition, it can also obtain scarce and strategic resources, and advance foreign technology. Thus, it will change the allocation of resources and enhance production efficiency in the home country, which leads to the reorganization of factors among industries in the home country and the improvement of total factor productivity. With the upgrading of industrial infrastructure and the improvement of total factor productivity, capital and technology will have a certain substitution effect on labor, which will reduce the percentage of labor employment. The evolution of industrial infrastructure will lead to older industries obtaining technological upgrades and improvements to their processes, thus increasing the demand for highly skilled labor. Meanwhile, the strengthening of the tertiary industry and the emergence of new industries will also provide more new jobs.

(4) The role of the marketization process. Marketization plays a particularly important role in the process in which OFDI acts on total factor productivity through the above channels, which includes promoting technological progress and innovation, improving the efficiency of labor resource allocation, and thus changing the transmission process of domestic employment and output. On the one hand, developing countries’ OFDI will accelerate the domestic market-oriented process in several ways. These include coordinating the relationship between the government and the market, promoting the development of the non-state economy, increasing the degree of marketization of the home country factor market and product market openness, speeding up cultivating market intermediary organizations, and promoting the construction of a domestic legal system. On the other hand, the improvement of marketization means that the market institutional environment required by open economic development has been improved, and the improvement of the market institutional environment will further promote the enterprises of developing countries to carry out foreign direct investment and improve open economic development.

At the same time, a good market environment will greatly benefit from the OFDI to improve the total factor productivity and promote technological innovation, thus improving the efficient allocation of domestic labor resources through increasing human capital, reversing the spillover of international technology, and upgrading the industrial infrastructure. Finally, the quality of the labor force and employees’ abilities are enhanced, and the demands for skilled labor will be enlarged. The growth of the tertiary industry and new industries bring more new jobs, while there is a labor force transfer between industries and departments, in which some parts of the labor force are replaced by capital and technology.

Therefore, the market-oriented institutional environment is not only one of the important channels by which the OFDI promote domestic employment through promoting domestic technological innovation and improving the allocation efficiency of labor resources, but also an important precondition for the development of OFDI and the effective exertion of OFDI on domestic employment [

23]. The impact of OFDI on domestic employment varies according to the degree of marketization.

3.2. Model

In order to empirically investigate the overall effect of China’s OFDI on domestic employment and the differences in the effect of OFDI on domestic employment in various regions with different marketization processes, this article uses the analytical method of Greenaway et al. [

24] and Islam [

25] for reference and establishes an extended dynamic regression model of labor demand on the basis of C–D production function.

Let the C–D production function be:

Among them, i denotes the cross-section units (province, city, district), t denotes period (years), Q denotes real output, K denotes capital stock, L denotes labor input, α, β respectively denote the capital and labor output elastic coefficients, A denotes the technical efficiency affecting output growth, and γ denotes the percentage of determinants of technical efficiency. Under perfect competition conditions, the manufacturer that pursues profit maximization will make its marginal output of labor (MP)

L) equal to wages (w) and the marginal output of capital (MP

K) equal to the corresponding use cost (c), so the production function can be further expressed as:

The labor demand equation of the manufacturer (or industry) can be obtained by rearranging the logarithm of Equation (2):

Among them, ,

, , and .

Assuming that the technical efficiency parameter A in the production function changes with time and is related to the development level of OFDI and the penetration degree of inward foreign direct investment (IFDI), the technical efficiency parameter A in the production function can be expressed as:

, δ

0, δ

1, δ

2 >0, in which T denotes the time trend, OFDI denotes outward foreign direct investment, and IFDI denotes inward foreign direct investment. So, the labor demand equation is expanded as:

For simplicity, let’s assume that capital price c is constant. Considering the dynamic adjustment process of labor demand in reality and the time delay of OFDI’s influence on technical efficiency, the labor demand regression equation needs to be added to the lagging variables of labor demand and OFDI. Therefore, this article establishes a dynamic panel data regression model to investigate the overall effect and regional difference of China’s OFDI on domestic employment. The specific regression equation is:

In Equation (5), β0 is a constant, βi denotes the regression coefficient, λi denotes the individual effect, and μit denotes a random perturbation term. The lag period of the OFDI variable is determined according to the significance of t statistics in the specific calculation process using actual data.

The variables involved in the regression in Equation (5) include: scale of employment (L), OFDI, IFDI, total output (Q), wage level (w), and time trend item (T). Among them, the unit employment in cities and towns (10,000 people) stands for employment scale (L). Real GDP (100 million yuan) stands for output (Q), and wages (w) are measured by average wage (RMB) per employee in cities and towns. To test the regression model robustness, OFDI and IFDI are substituted by OFDI flow (

$10,000) and IFDI flow (

$10,000), which are converted at the current exchange rates (average) into renminbi yuan, and the provincial urban fixed asset investment price index is used for the deflator (2004 = 100). Considering the availability of data, this article selects panel data of China’s 30 provinces from 2005 to 2017 (except for Tibet) to carry out the empirical research. All the data comes from China’s foreign direct investment statistical bulletin, China’s national statistics website (including the provincial city bureau of statistics website), China’s economic and social development statistical database, CEInet statistics database, etc. All of the above variables and indicators of statistical descriptions are shown in

Table 1. In order to reduce heteroskedasticity, all the variables in the regression of the model are expressed in the form of a natural logarithm except for OFDI and IFDI, which are due to the different selection of measurement indexes (see note in

Table 2).

4. Empirical Estimation and Result Analysis

4.1. The Overall Effect of China’s OFDI on Domestic Employment

This article uses the relative and absolute values of the main explanatory variables OFDI and IFDI respectively for the regression estimation. The two methods used in the empirical research were the Sys-GMM method in the dynamic panel regression model estimation proposed by Blundell [

26], and the dynamic fixed effects method proposed by Datta and Agarwal. The regression estimation results of all the models are shown in

Table 2.

From the test indicators of Sys-GMM estimation, all the Sys-GMM estimation results have passed Sargan and Arelano-Bond tests, indicating that the selection of tool variables for the model is reasonable, the residual sequence does not have a second-order autocorrelation, and the setting of the model is reasonable. Even though different measure indexes of OFDI and IFDI are adopted in models I and II, the regression results from the Sys-GMM and their dynamic fixed effects are very similar. Overall, the model is robust and reliable.

The estimation results of the model I Sys-GMM for the country as a whole show that:

(1) The previous employment had a positive effect on the current employment at the significance level of 1%, and the regression coefficient was about 0.6. The current output has a positive effect on the current employment at a significance level of 1%, and the regression coefficient is around 0.3. The current wage has a negative effect on the current employment at the significance level of 1%, and the regression coefficient is about –0.1. The regression coefficient of T is positive at the significance level of 1%. The above results basically accord with the general law of the market economy.

(2) From the perspective of the regression coefficient of IFDI, current IFDI has negative effects on the current employment at the 1% significance level, and the regression coefficient is about 0.01, which suggests that China’s FDI inflow has a certain crowding-out effect on domestic employment. According to the regression coefficient of IFDI and its lagging term, both IFDIi t-1 and IFDIi t-2 have a negative effect on current domestic employment at the significance levels of 5% and 1%, respectively. This result is related to the transformation of China’s economic growth mode in recent years and the lagging development of the domestic labor market. With the development of China’s open economy entering an advanced stage, technological progress and innovation are becoming a new driving force for economic development. More and more labor-intensive IFDI are replaced by capital-intensive and technology-intensive IFDI. In addition to the structural rigidity of the domestic labor market, the inflow of capital-intensive and technology-intensive IFDI will inevitably have a certain impact on the employment of the low-skilled labor force in the current period.

(3) According to the regression coefficient of OFDI and its lagging term, the current OFDI has a negative effect on domestic employment in the current period at the significance level of 1%, and the regression coefficient is about –0.01. Both OFDIi t-1 and OFDIi t-2 have a positive effect on current domestic employment at the significance levels of 5% and 1%, respectively. This estimation result shows that China’s OFDI has an obvious hysteresis on the promotion effect of domestic employment; that is, in the current period, OFDI has a certain degree of the substitution effect on domestic employment, but in the lagged period, OFDI has a relatively obvious promotion effect on domestic employment.

The possible explanation is that the promotion effect of China’s OFDI on domestic employment has an obvious lag, and the lag effect of one year has changed significantly from being a negative effect to a positive effect. The most direct explanation is that the response of employees is lagging behind. Generally, the training for employees in Chinese enterprises is mainly within a short period of one year. In order to adapt to new jobs, most employees receive short-term training to improve their employability in industrial infrastructure optimization. Thus, the effect of OFDI on employment has changed from the substitution effect in the current period to the promotion effect in the lagging period.

With the implementation of China’s “one belt and one way” strategy, most of the outward direct investment of Chinese enterprises has gone to developing countries with abundant resources, wide markets, and low labor costs. In the current period, this “horizontal investment” mode will have a certain degree of substitution effect on domestic employment. More importantly, it is a lagged-period process for OFDI to accelerate the process of marketization and act on total factor productivity, and ultimately form the promotion effect on domestic employment through the channels such as capital upgrading, the reverse spillover of international technology, and the upgrading of industrial infrastructure. In this process, a perfect market system environment is the necessary prerequisite to determine whether the promotion effect of OFDI on domestic employment can be effectively exerted. In the past 40 years of reform and opening up, the degree of marketization in China has been increasing, but there is still a big gap between China and the developed market economy. Especially due to the restrictions of the household registration system, housing, medical treatment, and children’s education, the structural rigidity of China’s labor market is still relatively large. Therefore, it hinders the rational flow and effective allocation of domestic labor resources to a certain extent in the current period.

4.2. Different Effects of OFDI on Domestic Employment in China’s Various Regions with Different Marketization Processes

(1) Areas classified according to their marketization process in China

The above-mentioned estimation of the overall employment effect of China’s OFDI based on inter-provincial panel data assumes that market institutional factors are a unified variable, and temporarily ignores the impact of the different market institutional factors in different regions on the domestic employment effect of OFDI.

Institutional factors are the core of development economics. To study the domestic employment effect of OFDI in developing economies, the vertical changes and horizontal differences of the system cannot be ignored, and the process of marketization is particularly critical among all the institutional factors. Since the reform and opening up, the degree of marketization in China has been continuously improving, which had established the basic premise for the effective exertion of the employment promotion effect of OFDI to a certain extent. However, as a large country with a vast territory and covering 31 provincial administrative regions, China’s regional economic development is obviously unbalanced. There are also great differences in the marketization processes of different regions. The low degree of marketization in some provinces has seriously hampered the role of OFDI in promoting domestic technological progress and innovation, and hindered the effective exertion of the employment promotion effect of OFDI. Source allocation efficiency is relatively low.

For a long time, Chinese scholars Fan Gang and Wang Xiaolu have tracked and synthetically evaluated the relative process of regional marketization in China. They regard the construction of various aspects of the market system as a process of systematic development and gradual improvement. They established the index system of China’s provincial marketization process by taking the relationships between the government and markets, the development of the non-state economy, the development of product markets, the development of factor markets, and the development of organization and law in the market into consideration. This index system not only compares the marketization process of each province horizontally, but also achieves the basic comparability along the time series, thus providing a relatively complete set of panel data to measure the marketization process in different aspects. Based on the research results of Fan Gang et al. (2011) and Wang Xiaolu et al. (2016), this paper ranks the market-oriented process of 31 provinces and municipalities by calculating the average of the relative index of the market-oriented process of each province and municipality in China from 2004 to 2015. The first 15 provinces and municipalities were designated as regions with faster market-oriented processes, and the last 15 (excluding Tibet) were designated as regions with slower market-oriented processes, as shown in

Table 3.

(2) Analysis of the impact of OFDI on employment in China’s various regions with different marketization processes

In the following part, the Sys-GMM method is used to empirically estimate the different domestic employment effects that OFDI has had in regions in different stages of China’s marketization process. In the dynamic regression process of the overall effect of OFDI on domestic employment, the absolute and relative variables of OFDI and IFDI have had little influence on the regression results, but if we want to further study the regional differences of the employment effect of OFDI, the regression results will be different. The empirical results of this paper show that the estimation results of OFDI and IFDI variables using their respective relative quantities as measurement indicators will be more significant, because China has a vast territory, the regional economic scale of provinces and cities varies greatly, the adoption of relative quantities can better reflect the development level and penetration degree of regional international direct investment, and the comparability is stronger. For this reason, in the following empirical analysis, both OFDI and IFDI variables adopt their respective relative quantities as measurement indicators. The theoretical relationship between marketization and OFDI is potentially endogenous; OFDI may enhance the process of marketization, but those regions with greater marketization may also be more likely to be the source of OFDI. In order to eliminate this endogeneity, the lag variable tool of dependent variable is adopted in this study. The empirical estimates and test results are shown in

Table 4. The

p values of the Sargan and Allano-Bond estimates are tested, and the regression model is reasonable and reliable.

(3) Robustness test of model

This paper uses Sys-GMM model to test the dynamic effects of OFDI on employment in regions in different stages of the marketization process in China, but the conclusion of the model needs to be further tested by robustness. For this reason, this study uses national GDP instead of the local output variable GDP in the robustness test of the model. The regression analysis of the key influence coefficient in the model is carried out with the same form and regression method. The test results are shown in

Table 5.

The results of the robustness test show that all the influence coefficients of the model are not only close to the original values, but also pass the significance test after the local output variable GDP is replaced by the national GDP. The test results are consistent with the previous analysis conclusions, which verifies that the test conclusions of the model are robust and reliable.

4.3. Discussion

From the regression coefficient of IFDI, there are also significant differences in the impact of IFDI on domestic employment in different regions of the marketization process: FDI has a certain crowding-out effect on domestic employment in regions with higher marketization degrees, while in regions with lower marketization degrees, the crowding-out effect of FDI on domestic employment is not obvious or has a certain promotion effect. This is because labor-intensive IFDI has been replaced by capital-intensive and technology-intensive IFDI in relatively high degree of marketization, while labor-intensive IFDI still accounts for a considerable proportion in relatively backward areas, which has played a positive role in promoting local economic growth and employment.

From the regression coefficient of w, the effect of wage on employment is negative. The effect of wage on employment is not significant in the regions with a fast marketization process, but the effect of wage on employment is significant in the regions with a slow marketization process. Since abundant labor resources and low wage levels are the main advantages of developing labor-intensive industries in provinces and cities with lower marketization, and lower wage cost is the basic prerequisite for enterprises to maintain production and employment; while in provinces and cities with higher marketization level, talents, technology and innovation are the foundation of enterprises. A higher wage level is an important guarantee to promote human capital, production, and employment.

The regression results of OFDI and its lagged items show that the dynamic effects of OFDI on domestic employment are obviously different in various regions with different marketization processes. For the regions with a relatively faster marketization process, the current OFDI had a negative effect on employment at the 1% significance level, and the regression coefficient was around 0.04; OFDIi t-1 had a positive effect on employment at the 1% significance level, and the regression coefficient was about 0.12; and OFDIi t-2 had no significant impact on the current employment. For the regions with a relatively slower marketization process, the influence of OFDI on current employment is not significant. OFDIi t-1 has a positive effect on current employment at the significance level of 5% at most, and the regression coefficient is about 0.03. OFDIi t-2 has a positive effect on current employment at the significance level of 1%, and the regression coefficient is about 0.03. This means that OFDI has an obvious substitution effect in the current period and a promotion effect in the lagged period on employment in regions where the marketization processes are faster. However, OFDI has no significant impact in the current period, and a certain promoting effect in the lagged period on domestic employment in regions with slower marketization processes. This result further indicates that the marketization process is an important factor affecting the development of China’s OFDI and the realization of OFDI’s domestic employment promotion effect. A good market institutional environment can effectively improve the efficiency of resource allocation, thus promoting domestic employment and output.

Realistic data show that the development scale of OFDI in provinces and municipalities with faster marketization processes is also larger. According to the data in the Statistical Bulletin of China’s Foreign Direct Investment in 2017, the total OFDI traffic in regions with relatively fast marketization processes in 2017 was 87.294 billion US dollars, accounting for 69.6% of China’s total OFDI traffic. Meanwhile, in regions with relatively slow marketization processes (excluding Tibet), the total OFDI traffic in regions was 16.321 billion US dollars, accounting for only 14.4% of China’s total OFDI traffic. The acceleration of market-oriented processes is conducive to the vigorous development of OFDI, especially for private enterprises to “go out”, and the expansion of OFDI scale will in turn accelerate the domestic market-oriented process, thus forming a virtuous circle. With the deepening of China’s market-oriented reform and the transformation and upgrading of the open economy, the effects of OFDI on promoting domestic total factor productivity, promoting technological progress and innovation, and effectively promoting domestic employment through various channels will gradually be reflected.

This further illustrates that a good market environment promotes technological innovation, so as to improve the effective allocation of domestic labor resources by increasing human capital and reversing international technology spillover. A good market environment can also optimize the industrial structure, improve the quality of the labor force and employee capacity, expand the demand for a skilled labor force, and ultimately promote the sustainable development of employment.

5. Conclusions and Suggestions

Large-scale OFDI in developing countries will have an important impact on their employment. Starting from the C–D production function, this article uses the Sys-GMM method to empirically test the overall effect of China’s OFDI on domestic employment and the dynamic effect of OFDI on domestic employment in regions with different marketization processes based on the panel data of 30 provinces and cities in China from 2005 to 2017. The main conclusions are as follows.

From the perspective of the whole country, the promotion effect of China’s OFDI on domestic employment is obviously lagging behind. OFDI has a certain degree of substitution effect in the current period, but there is a relatively obvious promotion effect on domestic employment in the lagged period. Whether the domestic promotion effect of OFDI can be effectively exerted is closely related to the domestic marketization process. The institutional environment of China’s domestic market has been gradually improved since the reform and opening-up time, but there is still a big gap between China and developed market economies, especially in the rigid structure of the labor market, which hinders the reasonable flow and effective allocation of domestic labor resources to some extent.

From the perspective of different regions, the domestic employment effect of China’s OFDI is obviously different. In regions where the marketization process is faster, OFDI has an obvious substitution effect in the current period and an obvious promotion effect in the lagged period on domestic employment. In regions with slower marketization processes, OFDI has no significant impact in the current period, but a relatively small promoting effect in the lagged period on domestic employment. This result further indicates that the marketization process is an important factor affecting both the development of OFDI and the effect of OFDI on domestic employment. A good market institutional environment can effectively improve the allocation efficiency of labor resources, thus playing a positive role in domestic employment. China is a large developing country and the development of regional marketization is uneven. Therefore, the Chinese government needs to improve the market mechanisms and related systems in different regions.

Comparing with the existing literature, we find the following. Firstly, this paper verifies that China’s OFDI has an alternative and complementary effect on employment. At the same time, the conclusions in high-income areas are consistent. At the same time, this paper also draws a distinct conclusion that the effect of China’s OFDI on employment is not a substitute or supplementary effect with easy answers, but rather one that involves lag and regional differences. It is only through considering this lag and difference that we can better understand the significance of China’s OFDI for the sustainable development of domestic employment, and grasp the practical value of marketization for China’s OFDI and sustainable employment.

In order for China’s OFDI to better promote domestic employment, the following suggestions are put forward in the light of the above conclusions:

Firstly, China should accelerate the improvement of its market mechanisms and related infrastructure construction. While promoting Chinese enterprises to “go abroad” and expand foreign direct investment, China should further reform the domestic market economic system, reduce excessive government intervention in the economy, foster the development of the non-state economy, expand the openness of product markets, improve the liquidity of factor markets, cultivate and build a complete intermediary service network, and improve the legal environment of market operation. As soon as possible, China should create a good market system environment for the effective exertion of the employment promotion effect of OFDI.

Second, there needs to be more support for the government’s public service function. The government should give more financial support in relation to affordable housing, urban and rural medical care, basic education, etc., to help people choose jobs and reduce the structural rigidity of the labor market. The government should also increase investment in vocational education, strengthen the vocational skills training of workers, improve the quality of human capital, while also meeting the high expectations of multinational enterprises in the current period. In the long run, the demand for skilled labor and international talents can improve the ability of domestic technology absorption and transformation. At the same time, the government should create a public platform for scientific research services, and guide and promote enterprises to increase investment in scientific research and development, so as to enhance the ability of domestic independent innovation.

Third, in order to promote the coordinated development of OFDI and IFDI in all regions, local governments should formulate relevant incentive policies according to their own economic structure characteristics, and combine OFDI with IFDI appropriately. For regions with high levels of economic development and high degrees of marketization, more efforts can be made to encourage large-scale foreign direct investment by enterprises. In particular, powerful multinational enterprises should be encouraged to integrate the global industrial chain and guide more capital and technology-intensive OFDI to develop vertical investment in developed countries in order to speed up the absorption and feedback of advanced technology and enhance their R&D and innovation capabilities. At the same time, attention should be paid to the introduction of capital and technology-intensive FDI in order to accelerate the adjustment of the domestic economic structure. For regions with low levels of economic development and low degrees of marketization, enterprises should not go abroad too fast. On the contrary, there is still great potential to develop local superior industries by reasonably introducing foreign capital. In addition, the government should also give more support and development space to domestic small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in policy to help them absorb more labor and employment.