1. Introduction

The sustainable development of any organization is closely related to the culture of that organization [

1,

2,

3]. Employees like to work in professional environments which resonate with their own values [

4]. Knowing that the human factor is the key to high performance and profit, successful organizations value and invest in employees who identify with the values of the organization. At the same time, the creation of a strong, coherent, and sustainable organizational culture represents an important priority for good organizational leadership [

5].

Organizational culture is an important concept in the field of management [

1,

2,

6,

7,

8,

9]. The interest for this concept was first developed in the private sector, but public institutions gradually discovered for themselves the value of this notion. The notion of ‘corporate culture’ is itself a witness to this reality.

1.1. Organizational Culture and the “Competing Values Framework”

The concept of culture was developed mainly in the fields of sociology, anthropology, and social psychology through studies which dealt with the ethnic or national characteristics of various groups [

10]. In general terms, culture represents the sum of all the differences that distinguish existence in a social group from that in another group or community [

11]. Culture is not hereditary, but it is acquired through learning. It is shared, it is not specific to single individuals but is transferred from generation to generation. It develops over time and is based on human adaptability [

12].

According to Reisyan [

13], culture has the capacity to shape the collective interpretations of events, as it includes collective memory and social practices. Consequently, culture is a societal element whose influences will also penetrate into organizations, with the implication that differences in organizations in different countries are often attributed, partially at least, to cultural differences [

14].

Edgar Schein [

15] defines the culture of a group as a pattern of common underlying assumptions which in the past have solved the group’s problems in terms of external adaptation and internal integration, assumptions which have functioned and are considered valid, thus being passed on to new members as the right way to perceive and address such problems.

Geert Hofstede et al. [

16] characterize organizational culture by referring to several characteristics: It is holistic (it is more than the sum of the parts), it is historically determined (representing the evolution of the organization over time), it is connected to elements of anthropological nature (symbols, rituals), is socially based (created by the human resource of the organization), and is difficult to modify.

The study of organizational culture has produced valuable theoretical and practical results in a wide range of fields [

17,

18,

19] among many others. Specialized literature contains a variety of models for describing organizational culture, based on existing research. Thus, in order to explain human behavior in a comparative manner, several cultural taxonomies have been developed over time, leading to the representation of general cultural profiles [

11]. What has been particularly influential has been a model which was developed by Kim Cameron and Robert Quinn, known as the “competing values framework” [

20]. Cameron and Quinn identified four types of culture, taking into account two factors: (i) Flexibility and discretion vs. stability and control; and (ii) internal focus and integration vs. external focus and differentiation. By representing these two dimensions in a matrix (

Scheme 1), the competing values framework appeared. The four quadrants correspond to four types of organizational culture that differ according to these two dimensions (and four values):

The clan archetype is considered to be representative of a family-type organization where members are involved in the decision-making process and teamwork is an important aspect of the work. Instead of rules and procedures, the typical features of organizations with a clan culture are teamwork and the organization’s commitment to employees. Customers are considered to be partners, the organization seeks to develop a pleasant work environment, and the major task of management is to facilitate participation, engagement, and loyalty.

Adhocracy is defined by flexibility and external interest, relying on innovation as a means of organizational functioning. Emphasis is placed on specialization and rapid changes within the organization whereby employees will cooperate on specific projects and then the group will divide. Zlate [

21] argues that the characteristics of adhocracy are opposed to those of bureaucracy: Stability is replaced by mobility and by temporary work groups, whereas in bureaucracy the employee avoids taking risks, respects hierarchy, looks for prestige, and refrains from creativity, and in adhocracy the individual is loyal to the profession, is not afraid of change, being determined to innovate in order to meet new challenges.

The hierarchy culture is characterized by stability and focuses on internal matters, being concerned with how the organization should address various tasks. One finds here a vertical approach to the organizational hierarchy, with an emphasis on efficiency. Procedures govern the work of people. Efficient leaders are good organizers and employees are expected to maintain a smooth organization. The long-term concerns are stability, predictability, and efficiency [

20].

Finally, market culture is characterized by focus and stability, along with external aspects. Competitiveness is valued and the transactions with external bodies are expected. Such an organization functions as a market, focusing mainly on external transactions and therefore on suppliers, customers, contractors, and regulators. Unlike the hierarchy culture, in which internal control is maintained by rules, by specialized jobs, and by centralized decisions, market culture functions primarily through economic mechanisms [

20].

The competing values framework allows for the fact that all organizations are likely to reflect all four types of culture to some extent. There is a dominant culture which is visible in the opinions of employees at all levels of the organization, however, frequently the cultural elements belonging to the other three typologies will also manifest themselves. Furthermore, a certain cultural pattern is not necessarily regarded as better than others.

The competing values framework makes use of the organizational culture assessment instrument (OCAI), in order to help interpret the organizational phenomena. The OCAI consists of six questions, with each question containing four options. Respondents share 100 points between these four options, depending on the extent to which they regard each option as reflecting the organization they are part of. The first round of answers to the six questions is labeled “Currently.” This refers to the culture of the organization at the time of completion. The questions are then repeated under the “Preferred” title.

The OCAI analyzes six dimensions that reflect major organizational aspects and thus reveal a certain cultural typology: Dominant characteristics (the overall organization, for example, a family-like place or a structured environment); organizational leadership (the leadership style, referring to characteristics like mentoring or smooth coordination); management of employees (the working environment, how employees are treated in the organization); organizational glue (bonding mechanisms between employees); strategic emphases (the areas that drive strategic goals); and criteria of success (what is rewarded within the organization).

Some examples of various items from the OCAI questionnaire include: “The organization is a very personal place. It is like an extended family. People seem to share a lot of themselves”; “The leadership in the organization is generally considered to exemplify coordinating, organizing, or smooth-running efficiency”; “The management style in the organization is characterized by teamwork, consensus, and participation”; “The organization emphasizes acquiring new resources and creating new challenges. Trying new things and prospecting for opportunities are valued”; “The organization defines success on the basis of the development of human resources, teamwork, employee commitment, and concern for people” [

20].

The answers given by the organization’s employees create a cultural profile that includes the dominant culture, its strength (the number of points awarded), as well as the discrepancy between the present situation and the preferred culture. The four options from the OCAI correspond to a cultural typology developed within the model of competitive values: The answers in the A options are related to clan culture, responses from the B options are related to adhocracy, options C refer to market culture, and options D refer to hierarchy culture.

The validity and usefulness of the OCAI has been investigated and demonstrated in a wide range of national and cultural backgrounds [

22,

23,

24]. Its application in various organizational settings has brought about valuable results both for the academic world and for different professional fields, ranging from business administration [

2,

24] to education [

1,

25,

26], healthcare [

9,

27,

28], construction industry [

3,

29], banking [

4], sport [

23], etc. It is expected, therefore, that its application will bring useful results in the field of social work.

1.2. The Organizational Culture of Social Service Organizations

Several recent studies have offered valuable contributions which are particularly relevant to the analysis of organizational culture in social service organizations. One such study is that of Patterson-Silver Wolf, Dulmus, Maguin, and Cristalli [

30], who have analyzed the relationship between workplace conditions and their impact on employees, services provided, and beneficiaries. Poor organizational culture not only negatively affects the workforce and prevents the implementation of new interventions, but also has a negative impact on the beneficiaries. The authors argue that, given the clear scientific evidence linking positive organizational culture to better outcomes for beneficiaries, organizations should make substantial efforts to improve poor working conditions.

Robbins and Coulter [

31] have advocated the creation of a culture that is receptive to the service user and this approach is all the more important in social services. The authors propose a number of specific actions which are regarded as suitable for creating a customer-focused culture: (i) Employment of people with personalities and attitudes which are compatible with the nature of the job, people who are friendly, attentive, tolerant, with good communication, and listening skills; (ii) creating opportunities so that the employees have a high level of control in their intervention with beneficiaries and in their decisions about workplace activities; and (iii) providing consistent encouragement to support the service users.

Lohmann and Lohmann [

32] have argued that social workers typically express their interest in a warm organizational culture, where service users feel welcome and employees are valued [

33].

Sawyer and Woodlock [

34] analyzed the issue of organizational culture in a residential institution. The strength of the culture in this kind of organization depends on several factors. The first is the size of the organization. Small organizations tend to have stronger cultures than large organizations that operate in multiple locations. The second consideration is the age of the organization. Culture evolves over time and an organization with a long history simply has a larger foundation on which to build culture. Finally, the way an organization is founded or developed influences the power of its culture.

It is thus possible to state that organizations operating in the field of social services or social work which have a strong culture will generally have greater consistency, while organizations with weaker cultures tend to be fragmented, have a low morale, and are prone to poor or inefficient communication. The effective support for service users must therefore be based on solutions-oriented interventions, which will, in turn, support the development of a healthy organizational culture.

Starting from these observations, the main contribution of the present study refers to the application of a well-known research instrument (the OCAI), whose value has been widely demonstrated at an international level (as indicated above), to a new geographical and professional field, a major social work organization in the South West of Romania. While the subject of organizational culture has been addressed in several recent studies focusing on Romania [

35,

36,

37], the relevance and usefulness of the OCAI is still widely under-researched in connection to Romanian organizations in the field of social work. Given the key role which a major social work organization (such as the General Directorate for Social Work and Child Protection) can have in the development of a sustainable society, it is our hope and contention that our study will provide significant theoretical and practical results.

2. Method

The purpose of this research is to identify the cultural profile within the General Directorate for Social Work and Child Protection (DGASPC) in the Gorj county, Romania, by analyzing the existing situation as well as the culture that is preferred by the institution’s employees. Identifying what the employees would perceive as the preferred (ideal) culture can be a starting point for cultural changes, if there are significant discrepancies between the culture that really exists and what the employees want.

The objectives of the present research are:

Identifying the dominant organizational culture type within the DGASPC Gorj, Romania;

Identify the strength of the dominant culture, as compared to other cultural typologies;

Observing the differences between the existing culture in the organization and the culture which the employees would prefer;

Observing the congruence between the cultural dimensions, according to the selected framework of analysis (competing values framework).

The research questions that guided this study relate to the real and the preferred cultural type and also the cultural typology: Is there a significant statistical difference between what people prefer and what actually exists, and what is the dominant cultural type in the organization?

At the time of data collection, DGASPC Gorj had 1266 employees, including 159 foster carers. Once foster carers were excluded from this lot (due to the fact that their work takes place outside of the organization), the total number of employees at DGASPC Gorj remained at 1107. Given the complexity of the institutions participating in the research, a non-probability sampling method was adopted through rational construction. The selection of the respondents was conducted on a voluntary basis through a public research announcement within the organizations participating in the study. Thus, the study includes a sample of 286 employees from DGASPC Gorj.

The average age of the respondents in DGASPC Gorj is M = 43.95 (SD = 8.18), the age being between 25 and 65 years. As for length of their employment in the organization, this is M = 13.47 (SD = 6.46)—between 1 month and 29 years. The gender distribution of the respondents is the following: 237 women and 49 men.

The OCAI questionnaire, which was described above, was used as the research instrument. The statistical data was then processed and analyzed with the help of the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 20, and the Excel program of the Microsoft Office 365 ProPlus package. Graphics generation was done with the help of the Excel program.

In regards to the ethics of the research, before filling in the surveys, the respondents were familiarized with the research objectives and with the subsequent presentation of the results. They were also assured about the confidentiality of any data that could lead to the identification of the respondents. All the surveys were filled in anonymously.

The analyzes carried out at the organization level took into account both the organizational culture dimensions found in the OCAI (i.e., the dominant characteristics of the organization, the leadership model, the management of employees, the elements that hold the organization, strategic emphases, the success criteria) as well as the dominant type of organizational culture. Concerning the dominant organizational culture, we also identified its strength in relation to the other three cultural typologies, and the congruence between the previously mentioned dimensions. An analysis of gender-based organizational culture was also carried out. The reference data consisted of the perceived values at the time of research and of the preferred values.

The limitations of our study should also be specified at this stage. First, the study is limited by the fact that only one organization has been analyzed (albeit a large and complex one). Secondly, the disproportionate number of women versus men in the sample could not be avoided given the very high percentage of female employees in Romanian social work services. The paucity of similar studies in the social work sector in Romania has not afforded us the possibility of providing relevant comparisons.

3. Results

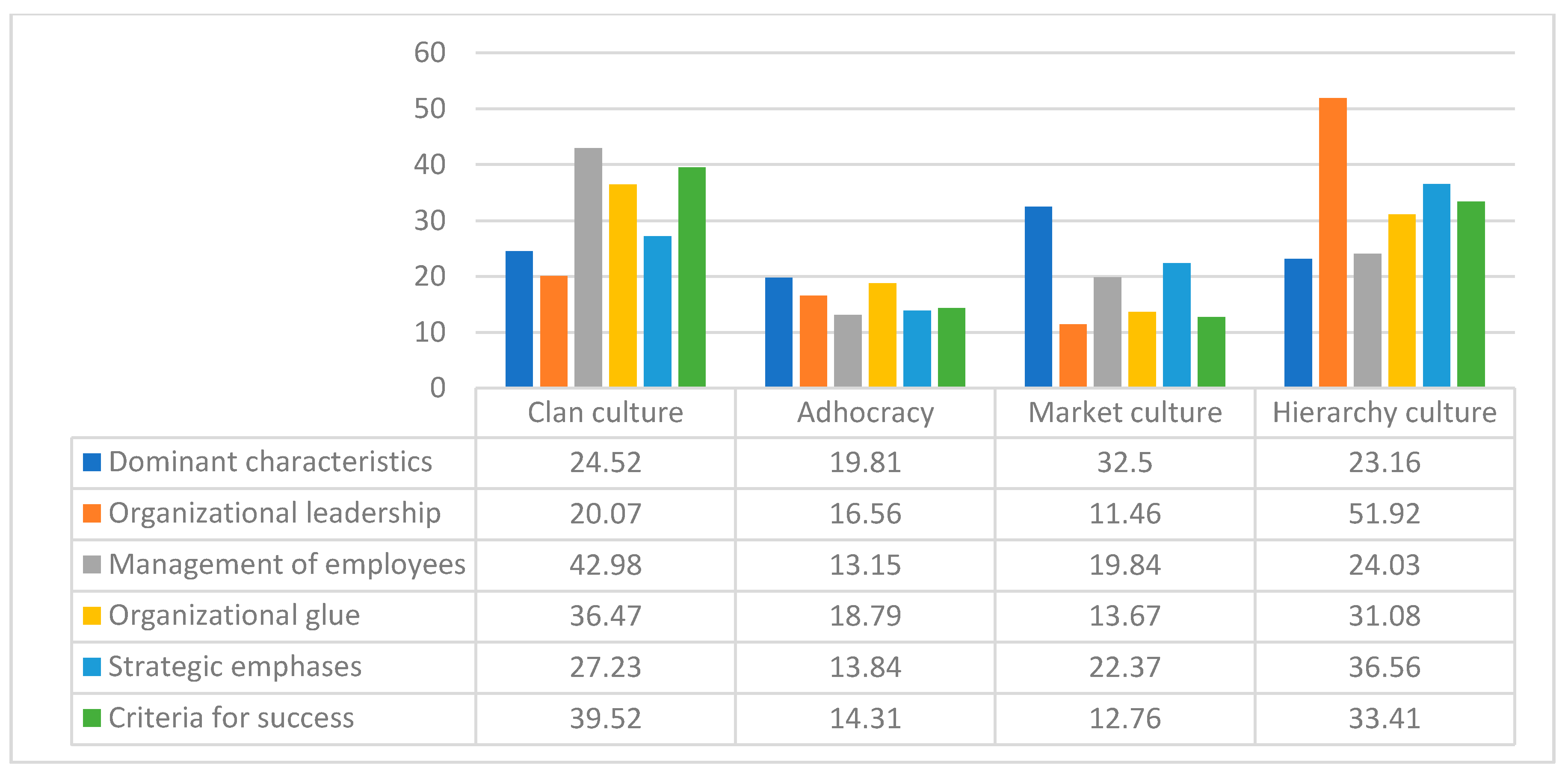

The figures in this section are a visual representation of the cultural typologies and the tables contain the corresponding statistical data.

3.1. Dominant Characteristics

The t test for pair samples was used to establish the differences between the perceived values at the time of the research and the preferred values for the dominant features at the DGASPC Gorj.

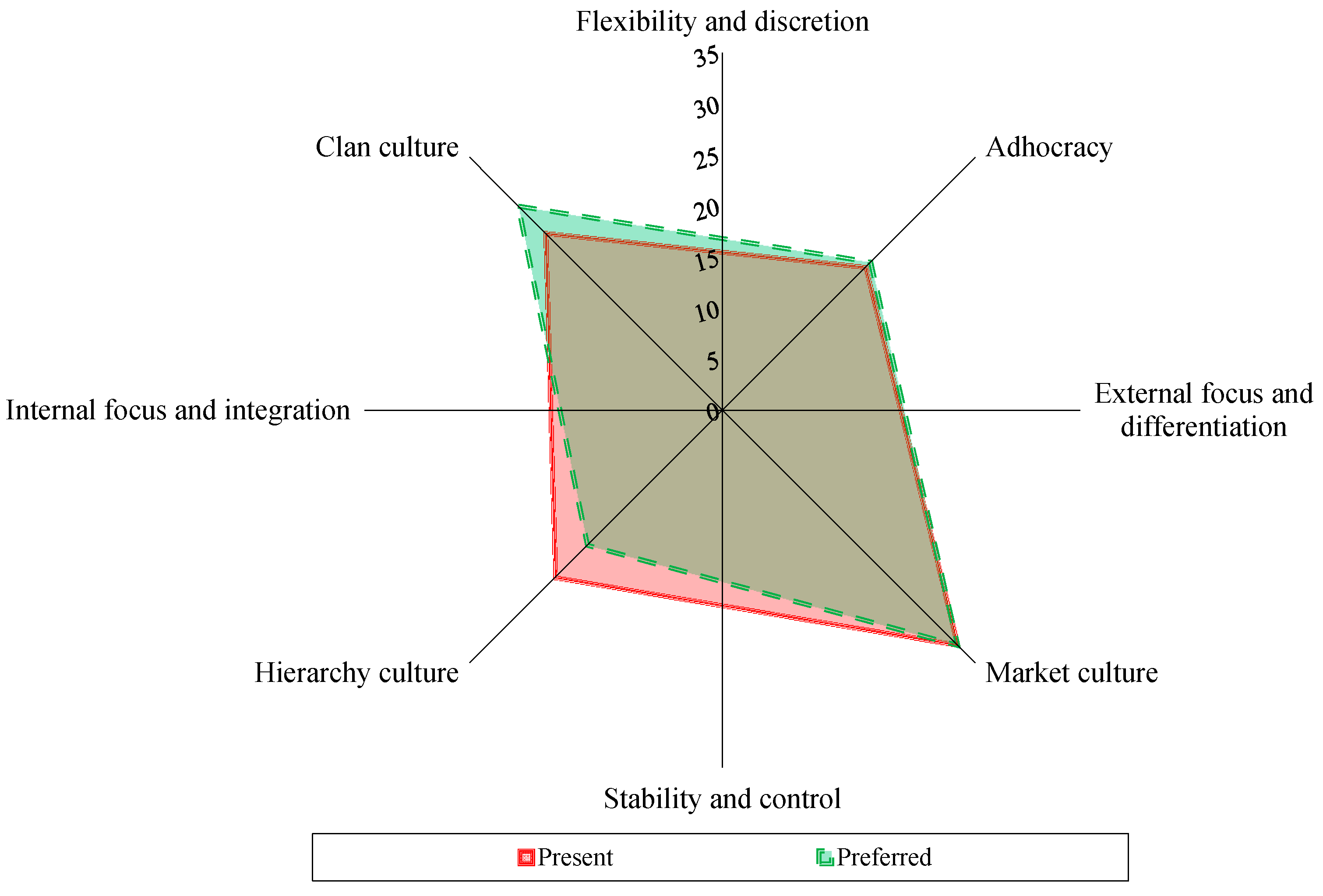

A statistically significant difference was found between the present score (

M = 24.52,

SD = 19.049) and the preferred score (

M = 28.26,

SD = 18.324) with respect to the dominant characteristics of the clan culture

t (285) = −4.058,

p = 0.000 (

Table 1 and

Figure 1).

Significant differences were also found in the dominant hierarchy characteristics

t (285) = 5.035,

p = 0.000 between the present score (

M = 23.16,

SD = 16.358) and the preferred score (

M = 18.70,

SD = 12.448,

Table 1 and

Figure 1).

Regarding the dominant organizational characteristics, we found a high score for market culture both in the case of the real and in the case of the preferred culture. Generally, this is not a typical feature of a public organization but rather of a private company. However, in this context, the choices of the employees may be due to a strong commitment to achieving goals, to satisfying service users, and to the desire for performance, which are typical characteristics of the market culture.

The results show that although the differences are statistically insignificant in the adhocracy and market-type cultures, employees would like the hierarchical model to be reduced in favor of the clan-type culture. This highlights the interest of employees for a family-like, personal environment.

3.2. Organizational Leadership: DGASPC Gorj

In order to highlight the characteristics of the leadership at DGASPC Gorj, the t test for pair samples was applied in order to determine the differences between the currently perceived values and the preferred values.

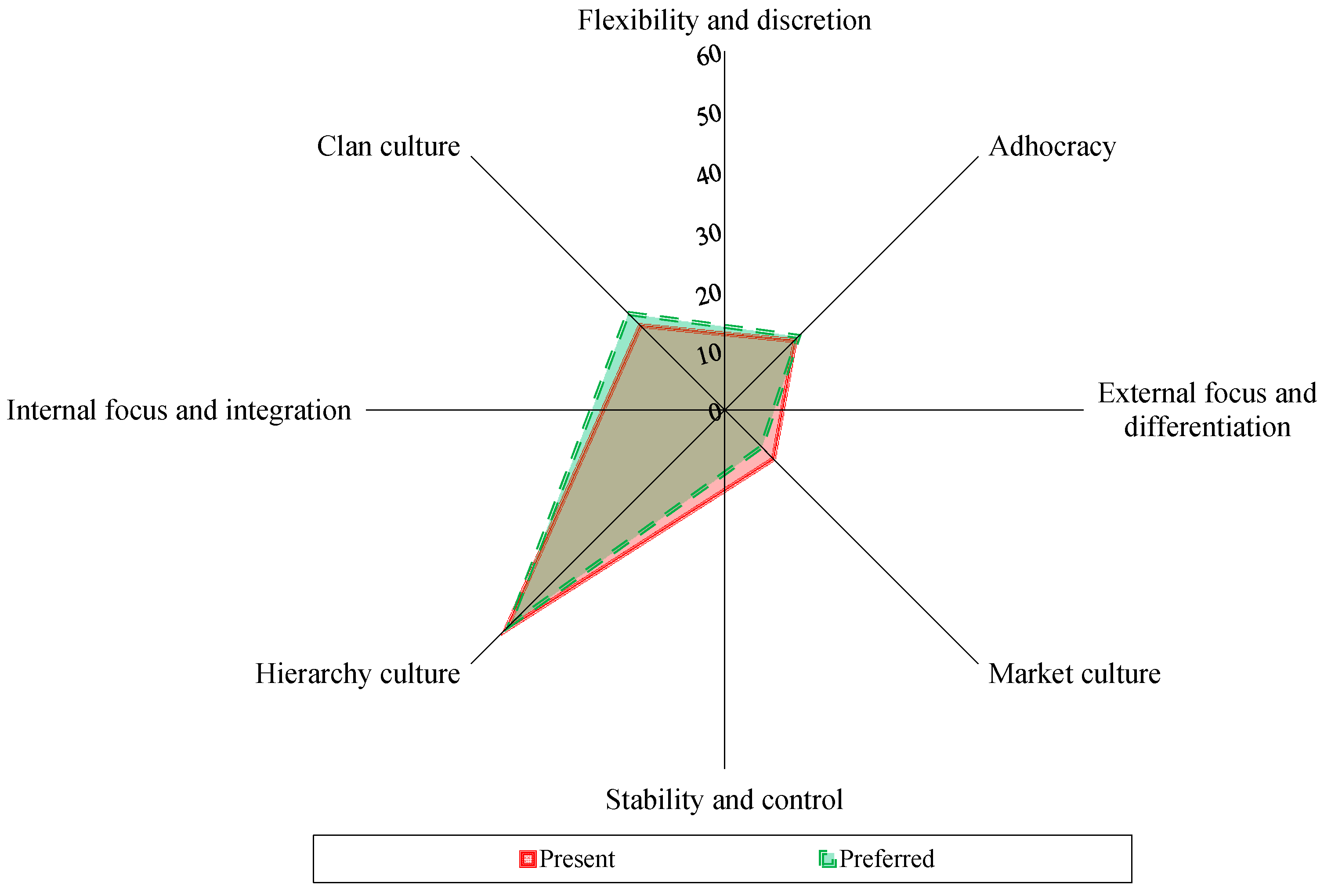

There was a statistically significant difference between the present score (

M = 20.07,

SD = 11.014) and preferred (

M = 22.92,

SD = 15.785) with respect to the clan leader

t (285) = −4.071,

p = 0.000 (

Table 2 and

Figure 2).

Significant differences were also found for the market leader

t (285) = 6.010,

p = 0.000 between the present score (M = 11.46,

SD = 9.999) and the preferred score (M = 8.72;

SD = 7.587,

Table 2 and

Figure 2).

Regarding the leader model, the respondents indicated the existence of values which are specific to the hierarchy culture (coordination, efficiency, thorough organization) both on the real culture component and on the preferred culture, meaning that the employees want a control-oriented leader. At the same time, there is a desire for a decrease in the values of the market culture, in favor of clan culture values. This indicates their desire to be coordinated by a person who is a mentor. This means creating the optimal environment for free discussions about professional and personal goals and concerns, honest feedback, and professional development.

3.3. Management of Employees

In order to establish the differences between the perceived values at the time of the research and the preferred values for the management style at DGASPC Gorj, the t test for the pair samples was applied.

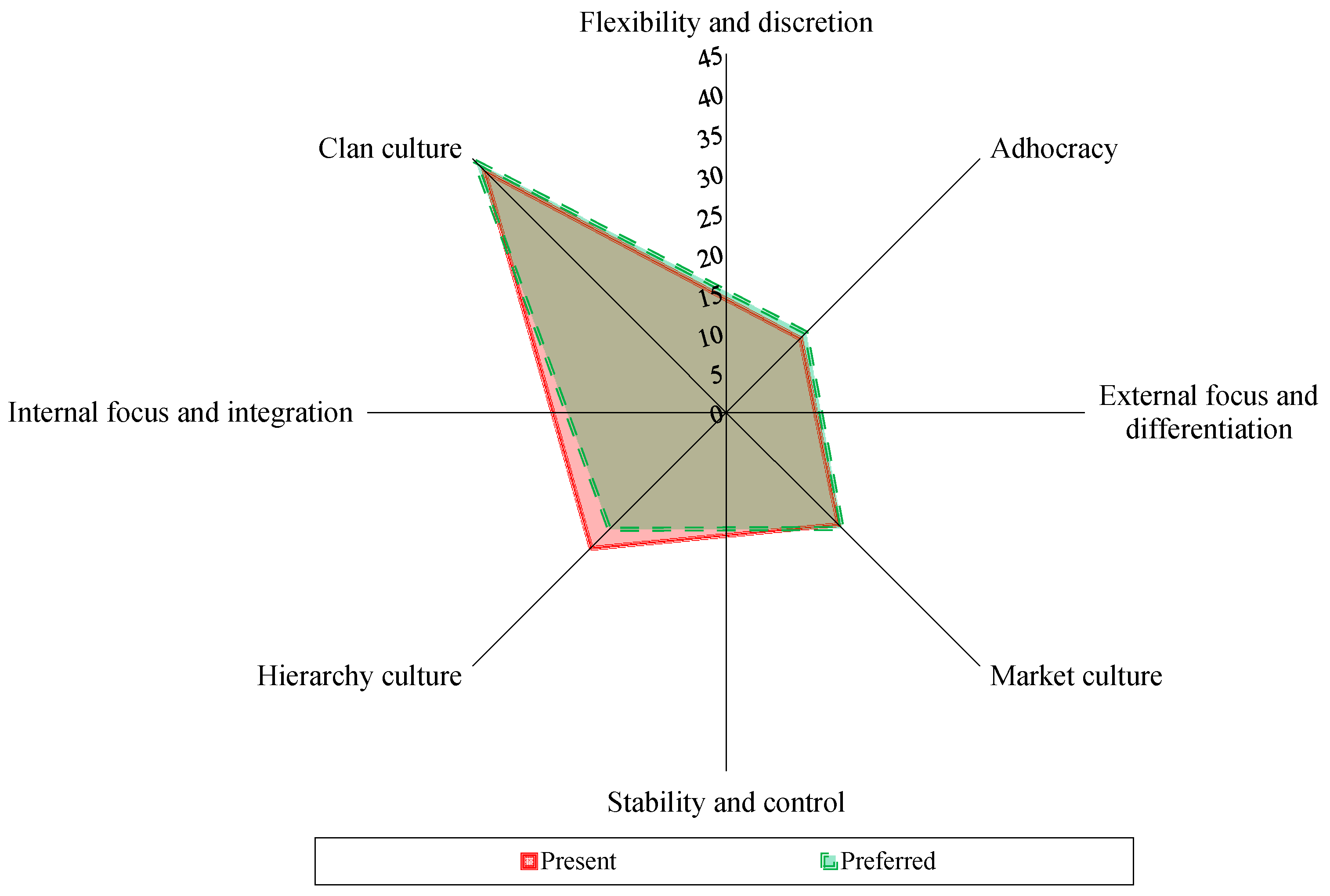

There was a statistically significant difference between the present score (

M = 13.15,

SD = 7.933) and preferred (

M = 14.16,

SD = 9.122) regarding the adhocracy culture

t (285) = −2.753,

p = 0.006. (

Table 3 and

Figure 3). Significant differences are also found in the hierarchy style management

t (285) = 4.407,

p = 0.000 between the present score (

M = 24.03,

SD = 13.748) and the preferred score (

M = 20.73,

SD = 11.783,

Table 3 and

Figure 3).

The results show that in terms of management of employees, the organization has a high score for a clan management style (where the staff is consulted in decision making and the organizational climate is family-friendly) both in the case of real culture and in the case of preferred culture.

3.4. Organizational Glue

The t test for pair samples was applied to establish the differences between the perceived values at the time of the research and the preferred values regarding the organizational glue at DGASPC Gorj.

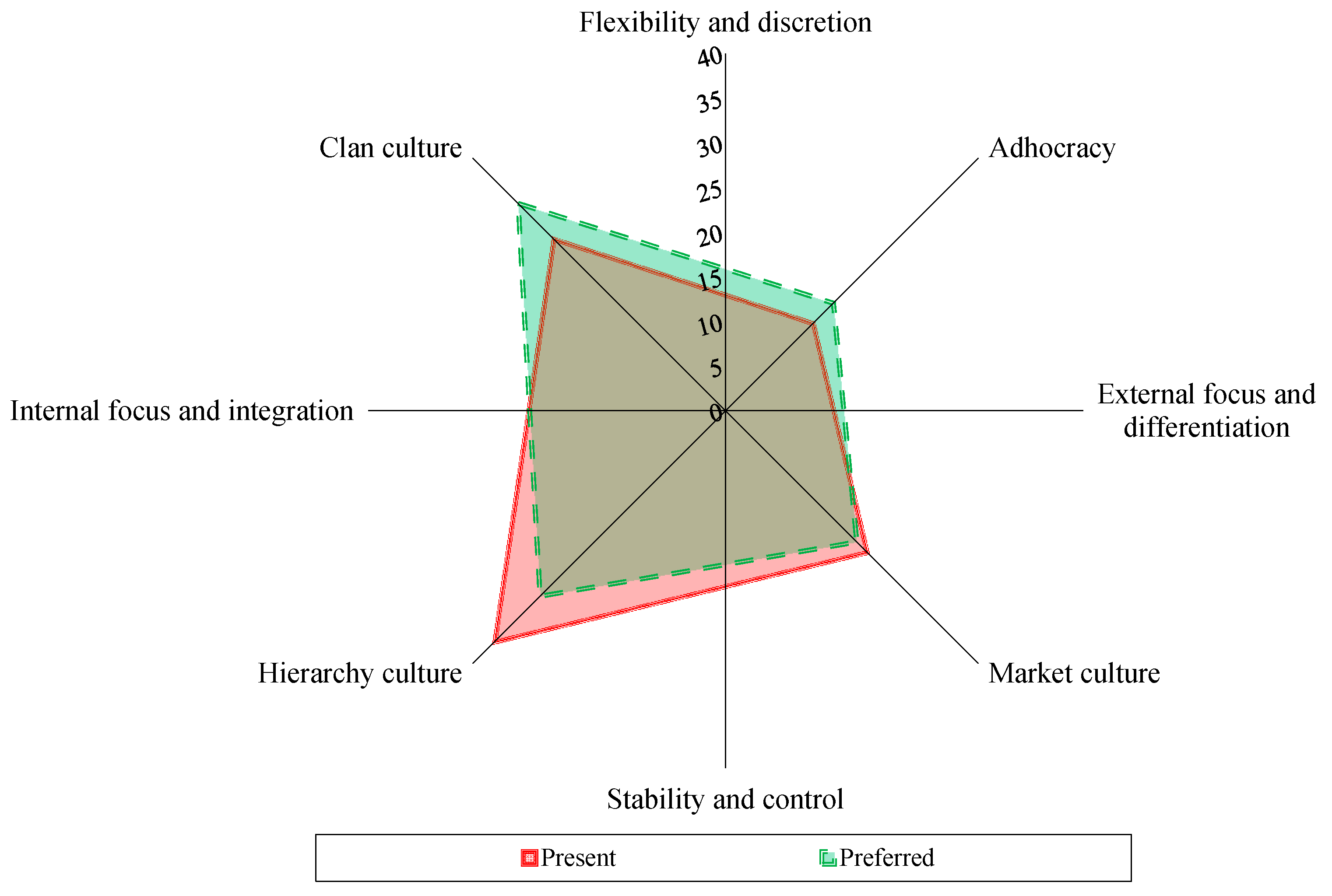

The most statistically significant difference was highlighted with regard to the elements of organizational glue relating to the hierarchy culture

t (284) = 7.368,

p = 0.000 between the present score (

M = 31.08,

SD = 17.567) and the preferred score (

M = 22.79;

SD = 15.422,

Table 4 and

Figure 4).

Significant differences were found both for the adhocracy culture elements

t (284) = −6.529,

p = 0.000 between the present score (

M = 18.79,

SD = 10.394) and preferred (

M = 21.90,

SD = 11.660), as well as for the clan elements

t (284) = −5.380,

p = 0.000 between the present score (

M = 36.47,

SD = 19.616) and preferred (

M = 42.65,

SD = 17.0,

Table 4 and

Figure 4).

The organizational glue relates to what is important to the organization and to the mechanisms that bring employees closer to it. The data shows that employees want to reduce their hierarchy orientation (emphasis on regulations, procedures, unfolding of activities without problems or disturbance) and an increase in clan culture values (mutual loyalty, trust, cooperation). Cooperation and trust among employees is a good way to promote positive multidisciplinary teamwork versus fragmented work where each employee is merely interested in performing their own tasks and filling in the required documents.

3.5. Strategic Emphases

In order to highlight the characteristics of the strategic emphases at DGASPC Gorj, the t test for the pair samples was applied in order to determine the differences between the currently perceived values and the preferred values.

The data indicates statistically significant differences in present vs. preferred scores, with regard to the strategic emphases of the clan culture

t (284) = −7.536,

p = 0.000, adhocracy culture

t (284) = −7.125,

p = 0.000, and hierarchy culture

t (284) = 5.927,

p = 0.000 (

Table 5 and

Figure 5).

Differences of medium significance are also found regarding the strategic implications of the market type culture

t (284) = 1.944,

p = 0.053 between the present score (

M = 22.37,

SD = 13.482) and the preferred score (

M = 20.75,

SD = 12.627,

Table 5 and

Figure 5). The results show that in terms of strategic implications, namely the directions and goals pursued by the organization, employees have indicated high scores for hierarchy culture, which means that the organization’s strategy is to maintain stability and have uninterrupted activities. For the preference component, employees want more values and behaviors which are specific to the clan culture (personal development, openness, and employee trust).

3.6. Criteria for Success

The t test for pair samples was used to determine the differences between the perceived values at the time of the research and the preferred values for the success criteria at DGASPC Gorj. The data indicates statistically significant differences in the present vs. preferred values, regarding the success criteria of the hierarchy culture

t (282) = 6.844,

p = 0.000, adhocracy culture

t (282) = −6.658,

p = 0.000, clan culture

t (282) = −6.206,

p = 0.000, but also with respect to the success criteria of market culture

t (282) = 2.642,

p = 0.009 (

Table 6 and

Figure 6).

In this organization, success criteria are primarily defined by results based on teamwork, cooperation, personal development, concern for people (all of which are typical of a clan culture), followed by efficiency-related positive results, as is the case in a hierarchy culture.

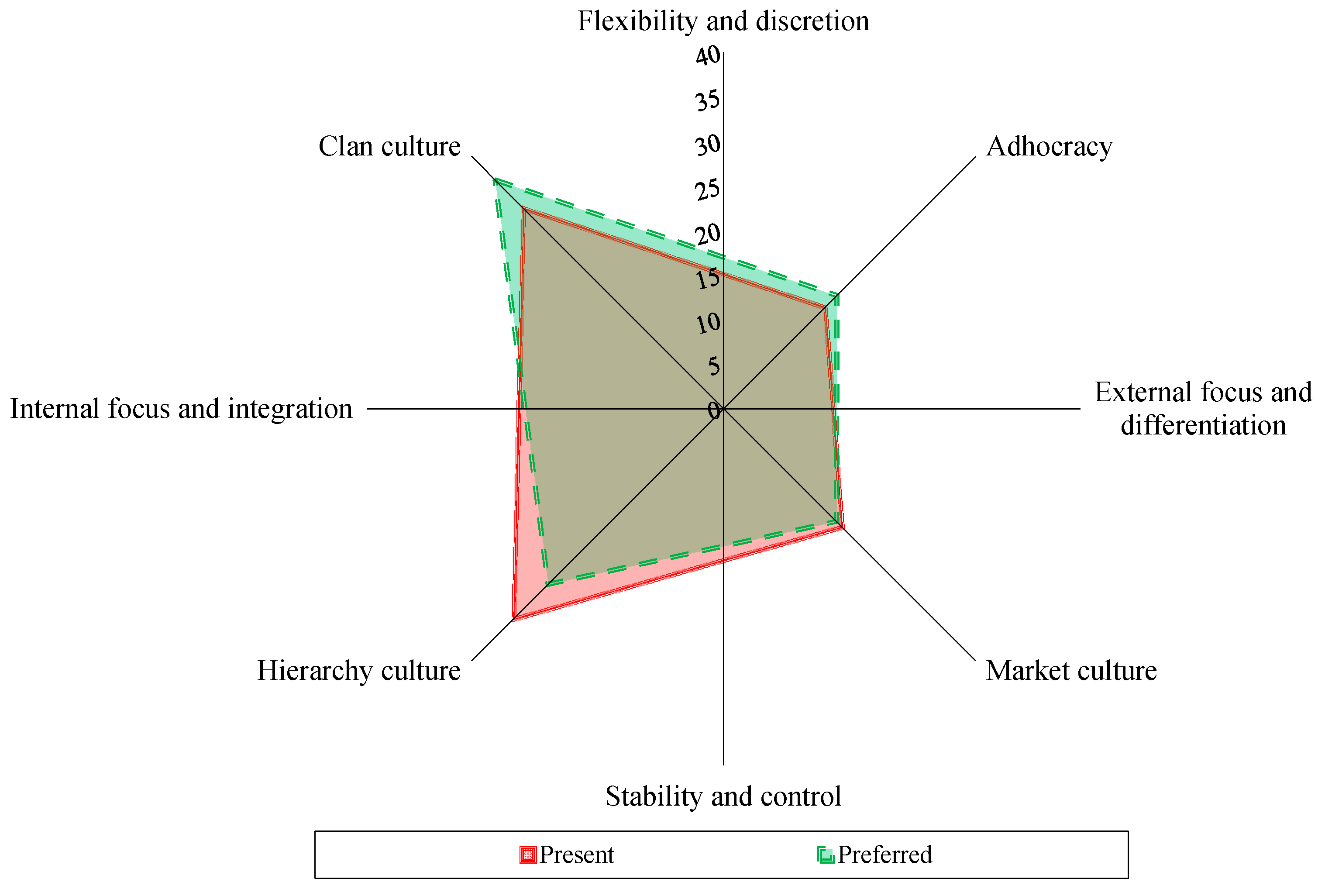

3.7. The Dominant Type of Organizational Culture

In order to highlight the statistical differences between the perceived values at the time of the research and the preferred values regarding the dominant organizational culture type at DGASPC Gorj, the t test for the pair samples was applied. The data indicates that there were no differences with a strong statistical significance (

Table 7 and

Figure 7). Nonetheless, there were differences with a slight to medium significance that revealed a desire for change in the future (according to authors Cameron and Quinn [

20], a significant number is in the case of a 10-point difference). The results show that the dominant type of culture was hierarchical, followed by clan type, market culture, and finally adhocracy culture. The change which would be expected refers to the employees’ desire to reverse the weight of the first two types of culture by a slight decrease in the adhocracy pattern and an increase in the market pattern.

3.8. Cultural Congruence

For DGASPC Gorj, the present situation indicates, in the case of the clan culture, an incongruence between dominant characteristics, management style, the organizational glue, and the criteria for success. Values for adhocracy culture are congruent. For the market culture, one can see a higher score for the dominant features of the organization. The hierarchy presents a discrepancy between the dominant characteristics of the organization, the leadership model and the management style. This indicates the existence of a leader who is generally authoritarian in the role of an administrator and coordinator, but who, when it comes to the general management of employees, are involved in discussions and decisions (

Figure 8).

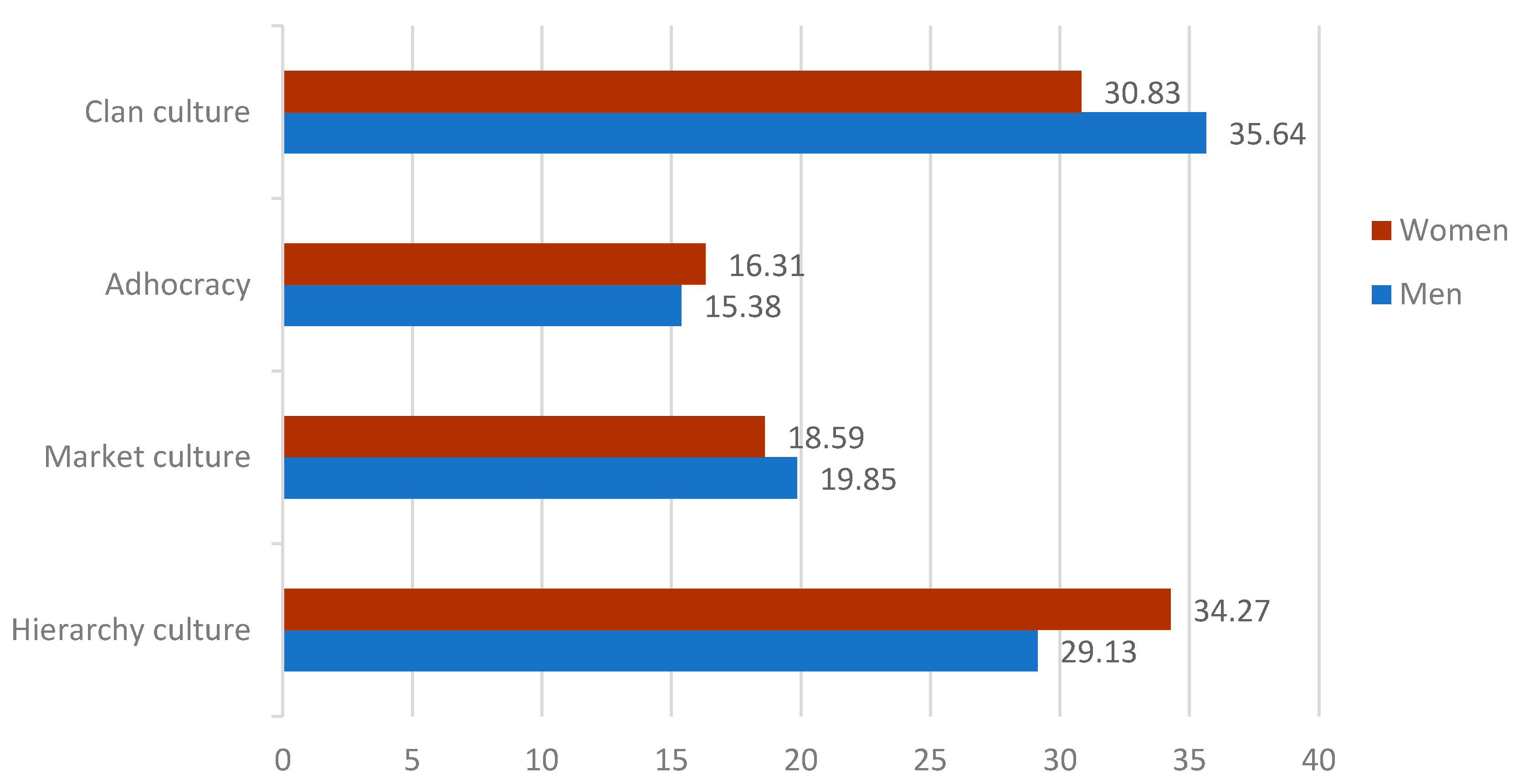

3.9. The Perception of the Organizational Culture, Based on Gender

For an analysis of organizational culture representations, based on gender, the Levene test for variance equality and the t test for independent samples (with a confidence interval of 95%) have been performed. The mean scores for the real organizational culture representations, according to gender, are shown below (

Figure 9).

The test value t (281) = 3.099, p = 0.002 (p < 0.05) shows that differences are significant for the clan culture (male, M = 35.64; female, M = 30.83). For the adhocracy culture (male, M = 15.38; feminine, M = 16.31), the test value t (281) = −1.217; p = 0.225 (p > 0.05) does not reveal significant gender differences. Similarly, for the market culture the test value t (281) = 1.535, p = 0.126 (p > 0.05) does not show differences in men’s representation (M = 19.85) vs. women (M = 18.59). Regarding the hierarchy culture, the value of the test t (281) = −3.528, p = 0.001 (p < 0.05) shows that the differences are significant on the level of gender representation (male, M = 29.13, feminine, M = 34.27).

With a higher clan culture rating, men perceived the organizational atmosphere as a more familial environment than women did. Women, on the other hand, regarded hierarchy as having a stronger presence within the organization.

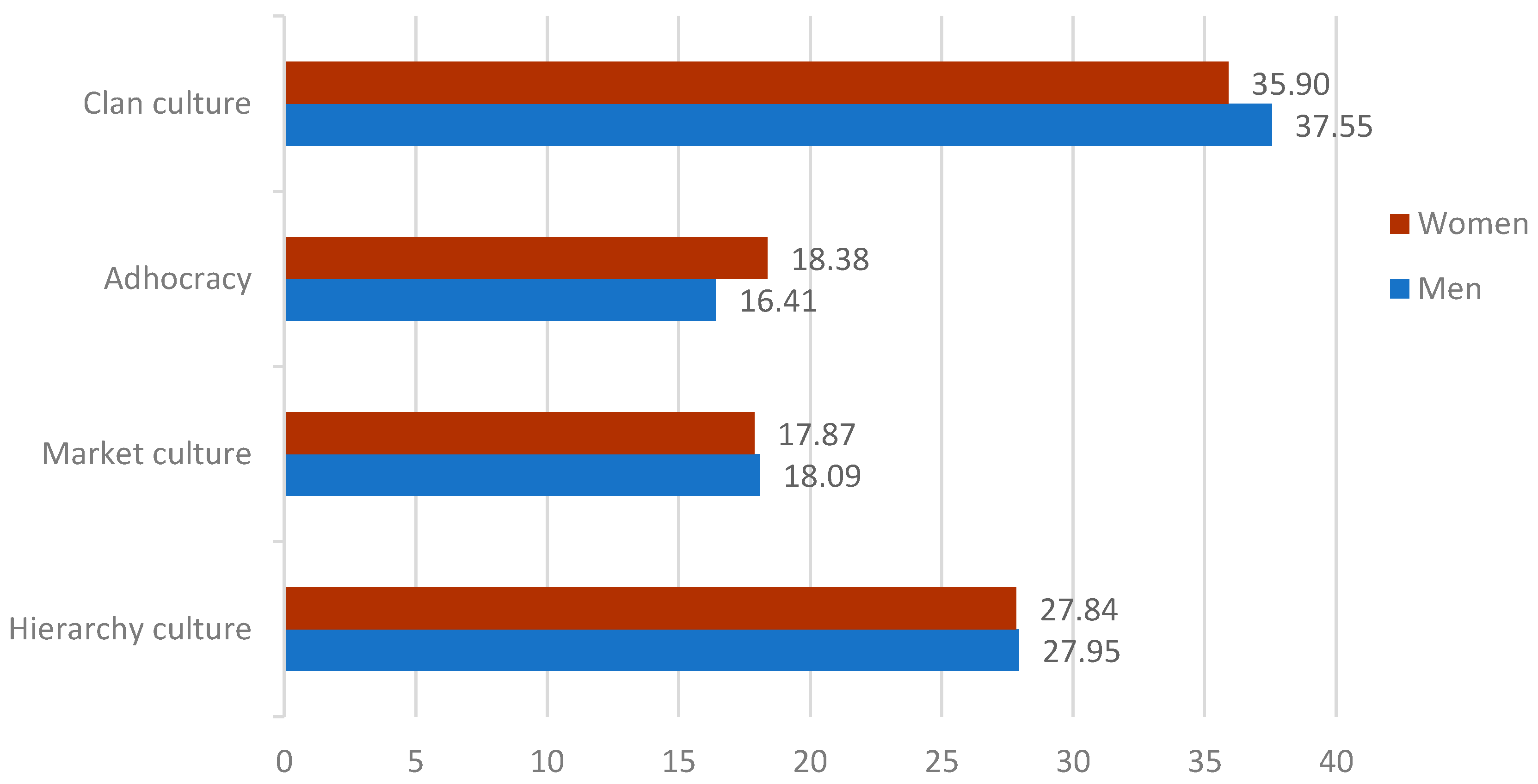

After testing the differences between the representations of women and men about the preferred organizational culture of DGASPC Gorj, it is evident that they are representative only for adhocracy

t (87.906) = −2.632,

p = 0.010, (

p < 0.01,

Figure 10). In the case of clan culture, the value of the t test (58.919) = 1.001,

p = 0.321, (

p >0.05) indicated the absence of significant differences between the two genders. The market type culture values [

t (281) = 0.263,

p = 0.793 (

p > 0.05)] and the hierarchy culture [

t (281) = 0.071,

p = 0.923 (

p > 0.05)] indicate the same recognition of the characteristics of the two types of culture at DGASPC Gorj by men (

M = 18.09,

M = 27.95 respectively) and by women (

M = 17.87,

M = 27.84 respectively). Regarding the hierarchy, women and men want a similar level of hierarchy as well as an increase in the values of clan culture, although men gave a higher score for this orientation.

4. Discussion

The existence of hierarchical culture as a dominant culture highlights the well-known realities of a large public institution, such as that of a DGASPC [

38,

39].

Cameron and Quinn [

20] characterize the organization with a hierarchy culture as a structured professional environment where procedures govern activity. In a social work organization, an excessive emphasis on regulations and standardized procedures leads to a situation where the primary concern in relation to service users is not so much about making good progress in reality but that their evolution looks good in documentation.

In a bureaucracy-oriented organization, the leaders boast their quality of good administrators. Yet, for a social work organization, a leader must also perform informal functions, must be able to motivate, to inspire, to be a model, all the more so given the fact that the employees of such organizations generally lack a supervisor who is a more experienced specialist and who can guide the employee when faced with professional difficulties. However, the results of our study show that the DGASPC Gorj employees are mainly looking for leaders who can exercise a stricter control, thus offering perhaps a stronger sense of security.

The organizational glue relates to what is important to the organization. In this case, procedures, formal rules, and predetermined intervention methods are important, as well as the assumption of institutional and professional identity [

40]. In a field like social work, where the main activity consists of working with people, it is no wonder that employees want a reduction in hierarchical orientation and an increase in clan culture values (mutual loyalty, trust, and cooperation). Cameron and Quinn [

20] state that maintaining a predictable, trouble-free organization is the most important strategic direction in a hierarchical culture. The results have shown that employees want to maintain stability, being likely to show resistance to change, even if they would aspire for greater personal development in the future.

In this organization, success is defined in terms of teamwork, of cooperation, and concern for people, a tendency which is typical of a clan culture but even more so, it is typical for good quality social work.

Concerning the dominant culture type, the results did not indicate strong statistical significance. However, the desire for change at a medium level (preservation of interior orientation and integration) was noticed, thus reversing the emphasis of prominent values within the organization (the values of a clan culture being preferred over those of a hierarchy culture).

Although the dominant culture in DGASPC Gorj is the hierarchy culture, the strength of this type of culture was not very high when compared to the other cultural typologies, since the score of the hierarchy culture is M = 33.36 and it was closely followed by the clan culture—M = 31.80. We can conclude that although the organization has a clear bureaucratic tendency, there is cooperation, trust, and mutual support among employees. Concerning the congruence of the cultural dimensions, they have not obtained completely uniform scores, but this may be due to the fact that DGASPC services operate in separate units, and employees can report, for example, to the Executive Director on issues such as dominant characteristics and to an office manager when thinking about a leadership model.

Differences between women and men do not pose problems for the organization, because although there is a certain gap between the scores, this gap is not a very significant one, given the fact that both genders have similar preferences. We cannot, therefore, speculate the existence of men/women subcultures. Nevertheless, an in-depth study focusing on differences between men and women regarding workplace culture could be a relevant aspect to explore in future research.

When discussing the conceptualization of various values in relation to cultural typologies, we can consider the following: the values that can be promoted in a clan culture (especially in the case of social services) are loyalty, communication, commitment, and interpersonal relationships; values corresponding to a social services adhocracy are medium and long term orientations, managerial innovation, and service development; within the market culture, social work organizations promote a focus on efficiency, goal orientation, and transformation in line with the social and economic contexts; the hierarchy culture values refer to strict guidelines for procedures and rules, efficiency, and uniformity.

This study has focused on analyzing organizational culture in a social work institution and although the perspective of the beneficiary regarding a positive organizational culture is of paramount importance, this has not been a focus in our present study. Once again, this could provide a venue for future research in the field.

Regarding the way our study compared to similar research in Romania, given the complexity and specific features of social service organizations, we have not been able to identify research conducted in the same type of organizations. Furthermore, we considered that comparing this study with organizations that are also part of public administration (city hall, county council, etc.) would not have been entirely relevant as social work institutions have a special objective, that of directly supporting vulnerable groups, managing child protection/adoption/foster care, activities which are unique to DGASPCs.

As for the practical implications of this study, we propose that managers in the organization nurture the interest for a clan-oriented culture. This can be achieved by informal gatherings, teambuilding activities, and an emphasis on teamwork and collaboration. Reducing bureaucracy does not depend entirely on the organization’s leaders but also on requirements established by higher institutions or legislation. We also recommend that managers continue to monitor the evolution of cultural typologies because changes or a need for change can occur over time, as culture can be flexible.

Public institutions in Romania are in a process of increased organizational change. The national and international social and economic contexts require that organizations be ready for constant and sustainable change. The analysis of the organizational culture captures the internal reality of the public institution and ensures the commitment to sustainable development and changes.

The reason why the study of organizational culture is important in the field of social work refers to improving communication in the organization [

41], developing appropriate managerial policies, and conducting organizational change, where appropriate. The culture of an organization inevitably evolves and changes over time, as a result of changes generated by various influences. Sometimes, however, changes in the organizational culture should be sought in a deliberate and purposeful way, especially if the existing culture negatively influences the organization. Thus, when the leadership of an organization considers the possibility of deliberate changes in the organizational culture, a healthy way of defining and enforcing those changes is to first evaluate the existing culture, and then explore the preferences of the employees. Simply deciding that things need to change, without careful planning and development may lead to resistance to change, and to the hampering of progress. An efficient approach to sustainable organizational change should be based on a detailed assessment of the organizational culture.