Abstract

With the increase in urbanization, intraurban residential mobility, which underlies urban growth and spatial restructuring, is gradually becoming an integral part of migration in China. However, little is known about the differences in residential mobility between locals and migrants, especially in urban areas in Northwest China. In this study, we aimed to fill this void by investigating the residential mobility patterns among Urumqi’s locals and migrants based on data from a survey and face-to-face interviews that were conducted in 2018. The results first show that the migrants with low homeownership rates relocated more frequently, but had less intentions to move within Urumqi, compared with the locals. A larger proportion of migrants than locals was forced to migrate. Evidence also suggests that the migration directions of locals and migrants differ: both locals and migrants tended to relocate from the southern areas, like Tianshan and Saybark Districts, to northern areas, like Xinshi and Midong Districts, which show the northward migration process of the urban population center in Urumqi. In contrast to the locals, whose net migration direction was from marginal areas to the central area, the net migration direction of migrants was from the central area to the marginal areas, contributing to the formation of migrant communities in the suburbs and spatial segregation between locals and migrants. Lastly, the locals’ intentions to move were widely influenced by age, ethnic group, type of employment, family population, housing area, and residential satisfaction; the migrants’ mobility intentions were mainly influenced by housing type and residential satisfaction. To attract more migrants to the urban areas in Northwest China, a more relaxed migrants’ household registration policy should be implemented, and the inequalities of the social security system and housing system between migrants and locals should be reduced to bridge the gap between migrants and locals.

1. Introduction

China has witnessed large-scale and high-intensity rural-urban and interregional population mobility since 1978, which has resulted in rapidly growing migrants in China’s metropolises [1]. Unlike other countries, China’s urban population mainly consists of two parts: the locals with local household registration (hukou) and the migrants without it, as specified by the specific household registration system [2]. The household registration system is a legal system through which the state collects, confirms, and registers the basic information of citizens, such as birth, death, kinship, and legal address in China. The household registration population refers to the person whose permanent residence has been registered by the public security household registration administration organ in their habitual residence. Compared with the locals, migrants in China’s cities, especially rural migrants, are faced with many disadvantages, including institutional barriers (no local hukou), social discrimination, low level of education (usually primary and junior middle schools), low income, poor social security, lack of legal protection, and low access to education, social security housing, and basic public health services [3]. The unequal urban-rural relationship in the pre-reform period has shifted into urban areas in the form of unequal intraurban relationships between residents with local hukou and migrants without local hukou in China [4]. With the continuing housing reform, intraurban residential mobility is increasing in China [5]. Residential mobility is the adjustment process of family housing consumption. It underlies much of urban growth and change [6], and is central to understanding urban dynamics and changing social and spatial stratification in cities [7]. The different choices regarding residential locations and spatial preferences between locals and migrants have reshaped population distribution patterns and sociospatial structures in urban China [8], and may lead to the segregation of social spaces to some extent. With the rise of housing mobility in urban China, urban studies and urban development must examine the residential mobility of locals and migrants in urban areas in Northwest China [9].

Based on a questionnaire survey and face-to-face interviews conducted in Urumqi, the capital of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region of the People’s Republic of China, in 2018, this paper describes the different residential mobility characteristics between locals and migrants, provides an analysis of the spatial segregation and population distribution arising from residential mobility based on the spatial assimilation theory, and identifies the critical factors that affect the mobility intentions of locals and migrants in the urban areas in Northwest China.

2. Literature Review

Intraurban residential mobility first emerged as a research topic during the late decades of the 19th century [10]. Studies in western literature can be summarized into five stages. Early western scholars, represented by the Chicago School, thought that the residential place in a city was determined by individual social status, family situation and economic income, and proposed the classical intraurban residential mobility theory, including invasion and succession theory, and filtering theory [11]. The second stage began in 1950s, which was the rise of the Behavior Study School. From the perspective of migration behavior, Rosie introduced the theory of family life cycle, and argued that the family life cycle could lead to changes in family structure and demand, and a family responds to these demands by adjusting family housing and relocating [12]. The third stage, which began in the 1960s, mainly involved the study of the spatial and quantitative characteristics of residential relocation, such as the distance and direction of relocation, residential mobility rate, etc. [13]. The fourth stage started in the mid-1970s and extended until the late 20th century, with the development of the Marxism School, focusing on the effect of social structure, economic development, and political factors on residential mobility. The fifth stage was from 2000 to the present (2019). With the trend in diversified development, the research on residential mobility is becoming more abundant, and the research methods are becoming more diversified.

Compared with the studies in western literature, the study on residential mobility in urban China started in the 1990s, and is significantly different in content given China’s unique political and economic development. With the development of new types of urbanization and the excessive growth of the urban population in China, intraurban migration is having an increasingly significant impact on the characteristics of urban spaces, such as residential forms, neighborhood communications, community cultures, etc. As a result, studies on intraurban residential mobility in China have been increasing [9]. Previous studies of intraurban residential mobility have primarily focused on four major concerns in urban China. The first concern is the temporal dynamics of the residential mobility rates and the spatial characteristics of the relocation direction and distance. Given the strong planned economic system in the pre-reform period, various management systems in Chinese cities largely restricted intraurban residential mobility, which resulted in remarkably low mobility. Since the implementation of economic reforms and opening-up policies, large-scale urban renewal, the construction of new development zones, and the urban housing system reform have prompted Chinese cities to develop into modern cities with active economies and high population mobility [14]. Using housing mobility data from a questionnaire survey, Liu and Yan [6] found that the residential mobility rates slowly started increasing in 1980 in Guangzhou, China. In terms of the spatial characteristics of intraurban mobility, the residential relocation was mainly short distance migration in China (for example, more than 80% of the relocations were within seven kilometers in Tianjin) [14,15,16]. The directions of residential mobility are various in different Chinese cities. There were two main relocation directions in Tianjin, the megacity in Eastern China: one from the old downtown to the new development urban areas, which is the process of population suburbanization; and another from the new development urban areas to the old downtown, which is the process of population agglomeration [14]. Residential mobility mainly occurred in the inner urban area in Shenzhen, which is located in Southeast China [17].

The second concern involves the factors or mechanisms influencing intraurban residential movements. The main factors influencing intraurban residential relocation in China can be analyzed on three levels: macro-sized government management and housing market level, the medium-sized work unit and community level, and the micro-sized level, which includes the family level and individual level. The government influences residential relocation behavior through various system reforms, urban planning, old city reconstruction, and housing demolition measures [18,19]. With the continuous improvement in the housing sales market and rental market, housing location choice has been increasingly diversified [20]. Work units affect residential mobility through work place relocation and welfare housing allocation measures [18,21], and residents relocate to pursue a better community living environment [22]. At the micro level, family life cycles, individual life courses [23,24], job changes, housing property [25,26], housing consumption [17], income levels, membership in the Chinese Communist Party [27], commuting distances [28], information channels on moving [29], and residential satisfaction [30] affect relocation behavior. Li et al. [27] analyzed retrospective historical residential information using a survey in Guangzhou from 1980 to 2001, and found that education and membership in the Chinese Communist Party increase mobility and gender is an important differentiator of residential mobility. Work units dominated the direction and process of urban population migration during the planned economy period (1949–1978). However, residential mobility has gradually been dominated by market demand and affordability migration in the market economy transition period since 1979. Based on in-metro travel times before and after job and/or home moves, Huang et al. [28] found that commuters whose travel time exceeds 45 min prefer to shorten their commutes via moves, whereas others with shorter commutes tend to increase their travel time for better jobs and/or residences.

The third concern focuses on the effect of intraurban relocation. The process and consequences of relocation have different effects on individuals, families and urban spaces. The new living spaces of residents after relocation are separated from their original social network spaces [31], and their daily behavioral spaces [32], cognitive functions [33], and physical and mental health [34] subsequently changed or were influenced. Relocation is usually accompanied by the improvement in residential satisfaction [35]. Intraurban residential mobility has a significant impact on the urban spaces’ expansion and restructuring, such as suburbanization [36], and socio-spatial restructuring [37].

The fourth concern focuses on relocation intentions and its determinants. Extant studies focused on the factors influencing different groups’ and communities’ relocation intentions. The determinants of these intentions to move include demographic characteristics and residential satisfaction [38]. Drawing on the survey data from three different types of residential neighborhoods in Guangzhou, China, He and Qi [5] found that relocation intentions vary in different residential neighborhoods; male respondents are more likely to have relocation intentions than women, and residents who have higher education tend to relocate. Yang et al. [9] investigated the residential mobility intentions of urban residents in Zhongguancun, one of the typical areas in Beijing, and found that most of the residents who have intentions to move have weak community identities. Using data from the historical blocks in Chinese cities, Jiang et al. [38] suggested that intentions to move are negatively affected by residential satisfaction and that older inhabitants have less intent to move than younger inhabitants in urban China.

Migrants have now become the main driver of urban population growth and change in China’s mega cities. Beijing’s migrants, for example, accounting for 62.61% of the total population growth, had an increase at an average annual rate of 11.47% (4.5 times faster than for the total population) in 1978–2010 [39]. Within the constraints of employment opportunities and the housing supply, most of the migrants live in the suburbs [40], ultimately forming migrant communities and influencing the urban socio-spatial structure. Given the new type of urbanization in China, studies on the intraurban relocation of locals and migrants will be key to understanding the socio-spatial restructuring and the residential segregation of locals and migrants [7]. Wu empirically assessed the intraurban migrant mobility in two of China’s largest cities: Beijing and Shanghai. Wu proved that demographic factors such as age and education are significant predictors of both actual moves and prospective mobility, and longer-term migrants seem to gain some degree of residential stability, thus making residential duration the single most influential factor of the mobility rate [41]. Liu and Yan used survey data that were collected in Guangzhou in 2005 to analyze the determinants of the residential mobility of the local and nonlocal population based on the life cycle theory. Liu and Yan argued that the household registration system had an important influence on individual’s intentions to move in urban China, and huge differences existed in the intraurban relocation behaviors of the local and nonlocal populations [6]. Drawing on data from two household surveys that were conducted in Guangzhou in 2005 and 2010, Li and Zhu [42] argued that locals moved mainly in the search for a better residence, and the single most important factor in the moves of migrants was job change. Studies on the intraurban residential mobility of locals and migrants focused on the factors influencing locals’ and migrants’ relocation. However, the spatial consequences of locals’ and migrants’ relocation are unknown, as are the similarities of the determinants of relocation intentions between locals and migrants. Although there is substantial literature on residential mobility in metropolises in Eastern China, such as Beijing, Guangzhou, and Shanghai, relatively little is known about intraurban relocation in Northwest China. This paper provides this information and extends the body of literature to the cities in Northwest China.

We aimed to answer the following questions: What are the differences in residential mobility between locals and migrants in Urumqi, a city in Northwest China? How does the residential mobility of the different groups affect the population distribution and the restructuring of the social and spatial stratification in Urumqi? We first used survey data with detailed personal relocation information from Urumqi in 2018, to compare and analyze the characteristics and the spatial consequences of locals’ and migrants’ intraurban relocation based on spatial assimilation theory. Then, we applied the binary logistic regression to understand the factors influencing locals’ and migrants’ intentions to move.

3. Methodology, Study Area and Data

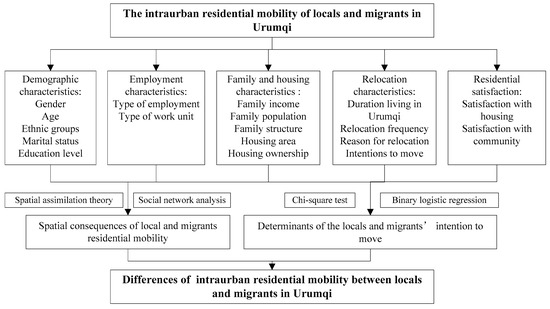

3.1. Research Framework and Methodology

The study’s framework incorporates spatial assimilation theory, which argues that the residential behavior of migrants proffers information regarding their levels of acculturation and socioeconomic mobility within the host community, and is one of the most widely used theories for explaining the spatial behavior of different groups’ relocation. Two opposite spatial forces, concentration and dispersion, are emphasized. The former induces residential segregation among groups and the latter leads to spatial assimilation of groups of locals and migrants [43]. Spatial assimilation refers to the latter situation in which migrants have similar spatial relocation patterns as the locals. Spatial segregation refers to the former situation in which migrants choose concentrated settlements, and have different relocation patterns from locals.

We used both social network analysis and binary logistic regression analysis in this study. First, we analyzed the characteristics of the relocatees and determined the differences between locals and migrants. Second, we used social network analysis to analyze the characteristics of interdistrict relocation to explain the social spatial segregation between local residents and migrants based on spatial assimilation theory. Social network analysis mainly uses matrix algebra theory from mathematics to analyze the characteristics and structures of social networks [44]. We established a matrix database for the collected relocation data in which a kind of “social relationship” was formed between addresses before moving and addresses after moving. The relocation matrix reflected migration flows and directions, and was mapped to display the spatial characteristics of relocation. According to the flows and directions of residential mobility, we analyzed the change in the spatial distribution patterns of the population. According to the differences in the spatial characteristics of relocation between locals and migrants, we analyzed the spatial residential segregation of locals and migrants. Third, we used chi-square tests (p-value < 0.05) to examine the interactions between the dependent and the independent variables. The independent variables that were statistically significant were included in the binary logistic regression model for further analysis to determine the factors influencing the mobility intentions of locals and migrants.

Take the following binary logistic regression [45]:

where denotes the p-value of the dependent variable (the value is between 0 and 1). In addition, denote the independent variables; denotes the intercept parameters; and denotes the coefficient of . If the p-value of is < 0.05, the independent variable is an influential factor. The analysis framework is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Analytical framework.

3.2. Study Area and Data Collection

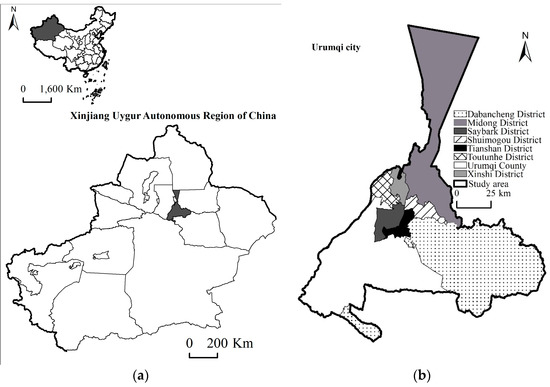

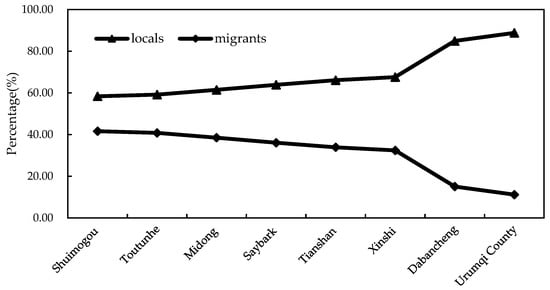

As the capital of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, Urumqi, which is located in the north piedmont of the middle Tianshan Mountains and the southern marginal zone of the Junggar Basin, is perhaps the westernmost metropolis among Chinese cities with a population of about 3.52 million in 2016 (Figure 2). The administrative area of Urumqi is 13,788 km2, which is divided into seven districts and one county. Tianshan District, Saybark District, Xinshi District, and Shuimogou District are located in the densely populated central area of the city. Toutunhe District, Midong District, Dabancheng District, and Urumqi County are located in the sparsely populated marginal area of the city. Of Urumqi’s population, 76.11% is local, and there are approximately 840,000 migrants from other provinces in China or other counties of Xinjiang according to the 2016 national economy and society developed statistical bulletin of Urumqi. With regard to the population distribution in Urumqi, the migrants appeared to have different distribution patterns from locals according to the sampling survey data of 1% of the population of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region in 2015 (Figure 3). The population of Dabancheng District and Urumqi County is dominated by the local population (over 84%). The proportion of locals remained stable at about 64% in Tianshan District, Saybark District, and Xinshi District. For migrants, Shuimogou District, Toutunhe District, and Midong District are the migrant agglomeration areas, where the migrant proportions exceed 38%.

Figure 2.

Location of Urumqi in China and the districts of Urumqi. (a) location of Urumqi in China; (b) the districts of Urumqi.

Figure 3.

The population distribution of locals and migrants in Urumqi according to the sampling survey data of 1% of the population of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region in 2015.

To empirically determine the different residential trajectories and mobility patterns between locals and migrants, we used a questionnaire survey and face-to-face interviews that were conducted in Urumqi in late 2018. The questionnaire survey and interviews that we designed included three parts. The first part requested the basic information about residents, such as gender, age, marital status, education background, occupation type, work unit type, family monthly income, family population, housing area, household registration type, etc. The second part was a relocation table about the retrospective residential trajectories of respondents, such as the frequency of intraurban relocations, the time of previous relocations, all historical residential places, dwelling types, reasons for relocation, and the important life events of the year of relocation the time of relocation. In this part, the respondents could also provide detailed reasons for relocation on the questionnaires, or answer the investigators’ questions about the reasons during face-to-face interviews. We determined the major reasons for relocation from simple statistical comparison. The third part asked about the residential satisfaction with existing housing and community and residents’ intentions to move. The respondents were residents who were no less than 18 years of age and had relocated within Urumqi.

Regarding the scope of investigation, the survey covered the seven urban districts and one county of Urumqi. Spatial stratified sampling and simple random sampling procedures were used in combination for the investigation. First, we determined the sample size in proportion to the total number of households in each district (Table 1). Then, we adopted the simple random sampling method for conducting the questionnaire survey and interviews in each district. Specifically, the survey took three forms. We conducted interviews and filled the questionnaires in the main business circles, large parks, or community service centers (such as Tieluju business circle, Youhao shopping mall, Hongshan park, Liyushan park, Xiaolvgu park, Kebei community service center, etc.), through which we completed 530 face-to-face interviews and finished 530 questionnaires simultaneously from 15 July to 31 August 2018. We issued the electronic questionnaires on the Internet with the help of the wjx.cn website, and received about 170 questionnaires from 1–15 August 2018. Because the number of questionnaires obtained by the above two methods did not cover the whole Urumqi city, we then conducted a large-scale questionnaire survey in one to three middle schools in each district/county in Urumqi, such as Urumqi No. 1 senior high school, No. 16 middle school, and No. 39 middle school, etc. With the help of school teachers, we sent out 1300 questionnaires from 20 September to 20 November 2018 to parents of students who had relocated. We sent out 2000 questionnaires through the above three methods. The incomplete and unanswered questionnaires were eliminated, and we finally collected 1515 valid questionnaires with detailed relocation information that met the requirements of this research (Table 1). The valid questionnaires included 986 locals’ questionnaires and 529 migrants’ questionnaires.

Table 1.

The statistical results of relocation survey in Urumqi.

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of Locals and Migrants in Urumqi Based on Sample Data

Locals and migrants were compared and analyzed in terms of demographic characteristics, employment characteristics, family and housing characteristics, relocation characteristics, and residential satisfaction. We checked whether the differences between locals and migrants were statistically significant using chi-square tests in the descriptive Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5. The results showed that most of the differences between locals and migrants were significant at the 0.05 level, such as age, ethnic groups, marital status, educational level, type of employment, type of work unit, family monthly income, family population, family structure, housing area, dwelling type, and intentions to move.

Table 2.

The sample demographic characteristics of locals and migrants in Urumqi.

Table 3.

The sample employment characteristics of locals and migrants in Urumqi.

Table 4.

The sample family and housing characteristics of locals and migrants in Urumqi.

Table 5.

The sample relocation characteristics of locals and migrants in Urumqi.

4.1.1. Demographic Characteristics

We compared and analyzed the demographic characteristics of the locals and migrants from five aspects: gender, age, ethnic groups, marital status, and education level. Table 2 shows that females accounted for nearly 57.0% of the local and migrant samples. The migrants in the sample, of which 58.37% were under 40 years of age, were markedly younger than the local population, of which 40.87% were younger than 40. The majority of the locals and migrants were Han population. The proportion of ethnic minorities in the local population (27.69%) was higher than that of migrants (11.72%). Regarding the marital status, there were more unmarried migrants (11.15%) than in the local population (6.49%). The overall education level of migrants in Urumqi was considerably lower compared with the local population. The education levels of the local population were mostly senior high school or higher (84.79%), whereas the education levels of the migrants predominantly were senior high school or lower (79.20%).

4.1.2. Employment Characteristics

We compared and analyzed the employment characteristics of the locals and migrants from two aspects: type of employment and type of work unit. Table 3 shows that more than 85.0% of the locals and migrants were employed. Employed migrants were primarily in the business and service industry (47.64%). Almost half of the migrants (48.58%) were self-employed. However, the local population was mainly employed as professional technicians (24.34%), in business and services (22.92%), or as enterprise managers (14.91%). Most of the local population worked in institutions (40.26%) and enterprises (19.27%), which are more stable and offer more decent salaries than being self-employed.

4.1.3. Family and Housing Characteristics

We compared and analyzed the family and housing characteristics of the locals and migrants from five aspects: family monthly income, family population, family structure, housing area, and dwelling type (Table 4). Regarding the family monthly income, the proportion of migrants incomes less than 6000 yuan (44.75%) was higher than that in the local population (38.44%). The proportion of migrants with family monthly income more than 16,000 yuan (3.78%), which is defined as high income, was lower than that in the local population (5.89%). Thus, the average family income of migrants was obviously less than that of the local population. In terms of family population, the average family population of both locals and migrants was approximately 3.1. The proportion of single residences for migrants (9.45%) was higher than that of the local population (5.88%). Most local and migrant families were core families of couples and children. In term of housing area, the average housing area of migrants was 81.4 m2, which is much less than that of the local population (99.3 m2). Regarding dwelling type, the majority of the local population had purchased housing, self-built housing, or lived in free housing (91.28%). However, nearly half of the migrants (43.86%) rented housing in Urumqi. Therefore, we conclude that the economic and housing conditions of migrants were worse compared with the locals.

4.1.4. Relocation Characteristics

We compared and analyzed the relocation characteristics of the locals and migrants from three aspects: relocation frequency, reasons for relocation, and intentions to move (Table 5). We defined relocation frequency as the average annual number of times that residents relocate within Urumqi. The duration of time living in Urumqi for the local population (average 28.8 years) was much longer than that for migrants (average 13.9 years). The average intraurban relocation times of migrants (1.55) was slightly higher than that of the local population (1.53). According to the average living time and relocation times of locals and migrants in Urumqi, we calculated their average annual relocation probability (average relocation times/average living time × 100%). The average annual relocation probability of migrants (11.15%) was two times as high as that of locals (5.31%). Thus, the migrants relocated more frequently than the local population in Urumqi.

In terms of reasons for moving, most of the migrants relocated due to job change (25.9%), housing demolition (20.42%), or improving residential environment (17.96%). The local population relocated mainly because of marriage (15.31%), job change (14.00%), or the replacement of larger-area housing (10.85%). We found that job change was the most important factor influencing migrants’ relocation. However, the most important factors influencing locals’ moving was marriage. Therefore, migrants’ relocation behavior had a closer relationship with job change, and the locals’ relocation behavior had a closer relation with family changes. The proportion of forced relocation in migrants, such as due to housing demolition, was higher than that of the local population. According to our face-to-face interviews, many rural migrants that did not own housing relocated several times due to housing demolition. The housing conditions were deplorable in the low-rent shanty towns in which they lived. Since the municipal government implemented the large-scale shanty towns renovation project in 2016, rural migrants have been evicted from the shanty towns that were going to be demolished. With the increase in of the renewal area, they began to frequently relocate from one shanty town to another, since they were in a vulnerable position and unable to successfully navigate the challenges of forced relocation. In the sample study area, 47.83% of migrants indicated a willingness to move, which was lower than that of local population at 54.44%.

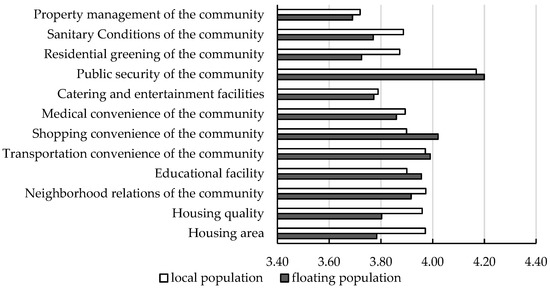

4.1.5. Residential Satisfaction

Residential satisfaction with housing and community was determined using a five-level scale, with one to five representing very dissatisfied, slightly dissatisfied, neutral, slightly satisfied, and very satisfied, respectively. We compared and analyzed migrants and locals in Urumqi in terms of the average residential satisfaction from 12 aspects, as shown in Figure 4. The average residential satisfaction of the local population with their housing and community (3.92) was slightly higher than that of the migrants (3.87). Both the locals and migrants were most satisfied and dissatisfied with the public security of the community and property management of the community, respectively. The locals were more satisfied with their housing area, housing quality, residential greening, and sanitary conditions of their community than migrants. Migrants were more satisfied with their educational facilities and shopping convenience of community than the local population.

Figure 4.

The sample average residential satisfaction of locals and migrants with housing and community in Urumqi.

4.2. Spatial Consequence of Residential Relocation

To describe the spatial consequences of the relocation process, we compared and analyzed the interdistrict relocation flows and net interdistrict relocation direction between locals and migrants in Urumqi.

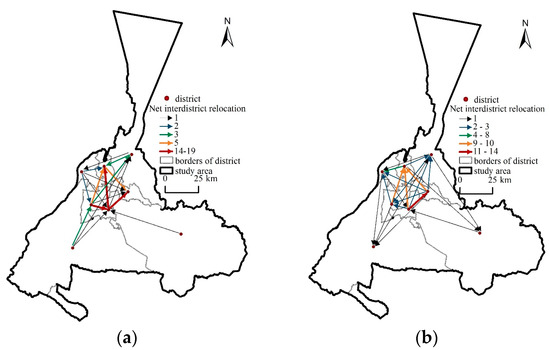

4.2.1. Relocation Flows and Directions of Locals

Regarding locals, most locals (82.07%) relocated within the central urban area, such as the Tianshan District, Saybark District, Xinshi District, and Shuimogou District (Table 6). The proportion of locals moving from the marginal areas to the central area (10.08%) outweighed that of the locals moving from the central area to the marginal area (7.28%), which shows the centralization of the locals. We analyzed the net interdistrict relocation network of locals. Figure 5 shows lines of different colors and numbers that refer to the net flow of the inter-district relocation. Red represents the highest net relocation flow and black represents the lowest net relocation flow. The arrows of the line represent the direction of net interdistrict relocation. Figure 5a shows the net interdistrict relocation network of locals. There are two main net migration flows directions of locals: one from the southern areas, such as Tianshan and Saybark Districts, to the northern area’s Xinshi District, and another from the western area to the eastern area, which is from Saybark District to Tianshan District, and from Tianshan District to Shuimogou District. Some locals relocated from the marginal areas, such as Urumqi County, Dabancheng District, and Toutunhe District, to the central area.

Table 6.

The sample flow matrix of locals’ interdistrict relocation in Urumqi.

Figure 5.

The net interdistrict relocation flows based on social network analysis in Urumqi: (a) locals; (b) migrants.

4.2.2. Relocation Flows and Directions of Migrants

Regarding migrants, 68.57% relocated among the central urban area (Table 7). The proportion of migrants relocating from the central area to the marginal area (17.96%) exceeded that of migrants relocating from the marginal area to the central area (10.20%), which shows the suburbanization of the migrants. Figure 5b shows the net interdistrict relocation network of migrants, and the two main migration directions of migrants: one from the southern areas, such as Tianshan District, Saybark District, and Shuimogou District, to the northern area’s Xinshi District; and another from the central areas, such as Tianshan District, Xinshi District, and Saybark District, to the marginal areas, such as Toutunhe District, Midong District, Dabancheng District, and Urumqi County.

Table 7.

The sample flow matrix of migrants’ interdistrict relocation in Urumqi.

4.2.3. Spatial Consequence of Relocation

We compared the relocation flows and directions of locals and migrants. First, both the locals and migrants relocated mainly within the central area, which was a highly active area of residential relocation. Second, most locals and migrants relocated from the southern area to the northern area in Urumqi. Tianshan and Saybark Districts, which are the old towns in the south urban area and mainly developed in the pre-reform period, were net outflow areas of both locals and migrants. However, Xinshi and Midong Districts, which are in the north urban area and mainly developed in the post-reform period, were net inflow areas of both locals and migrants. As corroborated by the statistical data from the Urumqi census in 2000 and 2010 and the sampling survey data of 1% of the population of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region in 2015, the proportion of locals and migrants in the Tianshan District and Saybark District gradually declined, and the percent of locals and migrants in Midong District significantly increased from 2000 to 2015 (Table 8), which is consistent with our survey. Limited by the topography of Urumqi (mountains surround the east, south, and west of the city), the direction of urban expansion has been dominated by south-north zonal expansion and supplemented by east–west axial expansion since the founding of the People’s Republic of China [42]. Therefore, the population outflow of old towns and the population inflow to the new development district show the northward migration process of the population center in Urumqi.

Table 8.

The distribution proportion of locals and migrants in Urumqi from 2000 to 2015(%). (a) locals; (b) migrants.

Some differences in relocation flows and directions were observed between locals and migrants. First, the net inflow direction of migrants was from the central area to the marginal area, which could lead to the loss of locals in the marginal areas. However, the net inflow direction of locals was from the marginal areas to the central areas, which could lead to an increase in migrants in the marginal areas. Since the introduction of urban land use system and housing system reforms in the 1990s, the housing prices of the central area have been rising [46], becoming unaffordable for most migrants and promoting the relocation of migrants to the suburban areas. The higher proportion of migrants who move to the marginal areas could in part explain the suburbanization and the increase of the migrants’ proportion in the marginal areas. As corroborated by the statistical data from Urumqi census in 2000 and 2010 and the sampling survey data of 1% population of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region in 2015, the proportion of migrants in the urban marginal areas rose steadily from 2000 to 2015 (Table 8). Shuimogou District, which is in the east urban area, was a net inflow area of locals but a net outflow area of migrants. Toutunhe District, Dabancheng District and Urumqi County, which are in the urban marginal area, were net outflow areas of locals but the net inflow areas of migrants. These different results of relocation between locals and migrants among Shuimogou District, Toutunhe District, Dabancheng District, and Urumqi County represent a spatial segregation of locals and migrants.

4.3. Determinants of Locals and Migrants’ Mobility Intention in Urumqi

4.3.1. Chi-Square Test

To determine whether an interaction existed between each variable and the intentions for intraurban relocation, we used the chi-square test in crosstab for the analysis. We identified the factors influencing moving intentions with respects to the demographic factors, employment factors, family and housing factors, and residential satisfaction. The p-values of the selected variables were less than 0.05 (Table 9) in the chi-square test; thus, statistically significant interactions existed between the independent and dependent variables. To better understand the complex mechanisms underlying the mobility propensities of locals and migrants, we then performed binary logistic regressions for the two different groups.

Table 9.

Chi-Square Test Results of migrants and locals.

4.3.2. Determinants of Locals’ Relocation Intentions

Regarding the binary logistic regression analysis of locals’ intentions to move, we used 13 variables of locals that passed the chi-square test as the independent variables (Table 9). We used the following question to determine if residents were willing to relocate: “Do you intend to move in the future?” The answer to this question (Yes or No) served as our dependent variable. From the results of the binary logistic regression of locals (Table 10), we found that the p-values for age, ethnic group, type of employment, family population, housing area, and satisfaction with convenience of catering and entertainment facilities were statistically significant, which were determined to be the important factors influencing the local population’s intentions to move in Urumqi.

Table 10.

Binary logistic regression results of locals.

For age, using “older than 60” as a reference, the intention to move for the local population that was aged between 18 and 30 years old was 2.772 times higher than those of locals aged older than 60. For those between 31 and 40, 41 and 50, and 51 and 60 years old, their mobility intentions were 3.142, 1.960, and 1.659 times higher than that of the reference group, respectively. Therefore, the intentions to move were high for the local population between 31 and 40 years old, and low for those between 18 and 30, 41 and 50, 51 and 60, and older than 60 years old, which is basically consistent with the results of previous studies that reported that aging inhibits residential mobility [47]. The higher mobility intentions of locals between 31 and 40 years old suggest that the potential improvement in living standards through relocation outweighed their attachment to their original residence, as well as their status as high income and the birth of a child. For ethnic groups, using minorities as a reference, the mobility intentions of the Han population with local hukou was 2.178 times higher than that of minorities with local hukou. That is, the local Han population was more likely to move than local ethnic minorities. With respect to the type of employment, using “other” as a reference, the residential mobility intentions of government staff, enterprise managers, professional technicians, business and service personnel, production and transportation personnel, farmers/herders, clerks, retirees, and the unemployed, were 0.494, 0.462, 0.535, 0.399, 0.411, 0.532, 0.391, 0.263 and 0.284 times higher than that of the reference, respectively. Therefore, the mobility intentions of different types of employment can be ranked high for professional technicians, farmers/herders, government staff, and enterprise managers, and low for business and service personnel, production and transportation personnel, and clerks. The intentions to move for retirees and the unemployed were the lowest, potentially because people with jobs like professional technicians and government staff tend to earn more better salaries than people who are production and transportation personnel or service workers. Marital status and education level were not factors affecting the mobility intentions of the local population in Urumqi. With respect to family population, families with more than six members were more likely to move than families with less than six members. Housing area was also a significant factor influencing mobility intentions. Using “more than 150 m2” as a reference, we found that those living in 0–50 m2, 51–70 m2, 71–100 m2, 101–120 m2 and 121–150 m2 were approximately 2.82, 1.891, 1.688, 1.249, and 0.597 times more likely to move than those with housing areas of more than 150 m2, respectively. Thus, the mobility intentions of those with different housing areas can be ranked as high for those with housing areas of 0–50 m2 and 50–70 m2, and low for those with housing areas of 71–100 m2, 101–120 m2, 121–150 m2, and more than 150 m2, the housing area of <50 square meters is extremely small for families or individuals. Local people living in small spaces were more likely to move, compared with those living in spacious housing. With respect to the satisfaction with the convenience of catering and entertainment, using “very satisfied” as a reference, the very dissatisfied, the slightly dissatisfied, the neutral, and the slightly satisfied were 1.235, 1.109, 1.103, and 0.938 times more likely to relocate than the very satisfied, respectively. Therefore, the mobility intentions can be ranked high for very dissatisfied with catering and entertainment and low for slightly dissatisfied, neutral, very satisfied, and slightly satisfied.

4.3.3. Determinants of Migrants’ Relocation Intentions

Regarding the binary logistic analysis of migrants’ mobility intention, we used the 12 variables of migrants that passed the chi-square test as the independent variables (Table 9), and the intention to move of migrants was used as the dependent variable. From the results of the chi-square test and the binary logistic regression (Table 11), we found that housing type, satisfaction with housing area and satisfaction with the residential greening of the community were the important factors influencing migrants’ intentions to move in Urumqi.

Table 11.

Binary logistic regression results of migrants.

With respect to housing type, using self-built housing as a reference, the ratio was one. The relocation intentions of those who purchased and rented housing were 0.539 and 1.186 times those of the reference group, respectively. Therefore, the mobility intentions can be ranked as high for those who rented housing and low for those who purchased housing and self-built housing. The migrant homeowners, such as those with self-built housing and who purchased housing, were less willing to move. For satisfaction with housing area, we found that migrants who were very satisfied with housing area were the least likely persons to move. Regarding the satisfaction with the residential greening of the community, the higher the satisfaction of the floating population, the lower the relocation intention.

5. Discussion and Suggestions

The aim of this study was primarily to investigate the differences in residential mobility between locals and migrants in Urumqi, a city in Northwest China, and the impact of the residential mobility of different groups on the population distribution and the restructuring of the social and spatial stratification in Urumqi.

In the above analyses, we confirmed significant differences among the characteristics of locals and migrants in terms of their demographic characteristics, employment, family and housing characteristics, relocation characteristics, and residential satisfaction. For example, the overall education level of migrants in Urumqi was low compared with the local population. The locals have more access to the stable and decent jobs in institutes and companies. The homeownership rate and average housing area of migrants were significantly lower than those of locals. The results of this study are consistent with the results of prior studies [6,41,42,48] with respect to the residential mobility of locals and migrants in China in that migrants have evidently higher mobility frequency than locals, and job change is the most important factor influencing moving. The housing demolition due to the urban renewal policy has had unintended effects on the displacement of residents’, which has been worse in urban China, as consistent with the study of western cities [49], and we found that housing demolition could result in the frequent relocation of non-homeowner rural migrants. The municipal government should pay more attention to the problem and reduce the social conflicts and disharmony caused by urban redevelopment and relocation.

Regarding the spatial consequence of relocation, the main relocation directions of both locals and migrants was from the south to the north, which reflected the northward shift of population center in Urumqi. As Yang and Lei found [50], the urban population distribution has gradually evolved from a single-center distribution pattern in the southern area, Tianshan and Saybark Districts, to a dual-center distribution pattern with the southern center in Tianshan district and Saybark district and the northern center in Xinshi district from 1982 to 2010. Our results are basically consistent with the previous research on the spatial-temporal distribution of the population in Urumqi, and we further analyzed the evolution of urban population distribution patterns from the micro-perspective of residential mobility. From the perspective of suburbanization and spatial segregation, we found an obvious relocation of migrants from the central area to the marginal area. However, the locals did not show a significant trend of suburbanization. The dispersion of locals and the agglomeration of migrants in the suburbs contributed to the formation of migrant communities and the spatial segregation of locals and migrants in Urumqi. Compared with the eastern cities in China, such as Shanghai, we found that the residential differentiation of locals and migrants was apparent, and residential spaces of migrants were further marginalized with urban expansion in Shanghai [51]. Therefore, Urumqi is similar in suburbanization and spatial differentiation of locals and migrants to the eastern cities in China. The many migrants moving from the central areas to the marginal areas may aggravate the spatial inequality because the spatial distribution of employment is mainly concentrated in the central area [52], and public service facilities, such as public transport and primary and secondary schools [53], are not relatively complete and convenient in the suburbs. These results have important ramifications for urban migrant management and control. Governments should acknowledge the spatial consequences of relocation. More attention should be paid to alleviating the spatial differentiation and segregation of locals and migrants and reducing the emergence of disadvantaged migrant communities.

Regarding the mobility intention of locals and migrants, we found that locals were significantly more willing to move than migrants. More than half of migrants were willing to stay, which reflects their demand for permanent residence and their lower ability to move. As evidenced by the binary logistic regression analysis, the factors influencing locals’ intentions to move appear to be different from those of migrants. As expected, age, ethnic group, type of employment, family population, housing area, and residential satisfaction were the factors influencing locals’ relocation intentions, which is consistent with the literature about residents’ mobility intentions in urban China [54] and western cities [55]. However, the migrants’ mobility intentions were mainly influenced by housing type and residential satisfaction. The type of employment and other demographic factors did not have a significant influence on migrants’ intentions to move, which was contrary to the locals in Urumqi.

As a city in Northwest China, Urumqi is located in the core area of the Silk Road Economic Zone. According to the latest urban planning guidance of Urumqi in 2014, future urban development should further attract migrants from other provinces and other counties in Xinjiang to Urumqi, to expand urban population scale. To achieve this, a more relaxed migrant household registration policy should be implemented, and the unfairness in the social security system and housing system between migrants and locals should be reduced to improve the city’s tolerance, to promote the citizenization of floating population, and to bridge the gap between migrants and locals.

Our study complements the prior research on residential mobility rates and reasons for relocation, and contributes to the literature by further providing evidence of the differences in relocation between locals and migrants in urban areas in Northwest China. Although this study provides some insights into the spatial differentiation that is caused by the relocation of locals and migrants, there is still room for improvement and extension. We have not conducted a survey about the formation of typical migrant communities, which could better support the study. We plan to further extend this study in the future.

6. Conclusions

The social segregation and spatial differentiation caused by residential moves of locals and migrants in Chinese cities are becoming increasingly obvious and require more research. Regarding the residential mobility of locals and migrants in urban China, studies have mainly focused on the factors influencing intraurban relocation and the residential mobility rate in Eastern China, without considering the differences in relocation between locals and migrants, especially in the urban areas of Northwest urban China. Thus, we first compared the basic characteristics of the locals and migrants in Urumqi based on the data from the intraurban relocation investigation in 2018, and then analyzed the spatial consequences of intraurban relocation of locals and migrants based on the spatial assimilation theory. Finally, we explored the factors influencing the relocation intention. Our results show the following:

- (1)

- Regarding the characteristics of locals and migrants who had relocated in Urumqi, overall, the migrants were younger than the locals, and the education level of migrants was significantly lower than that of the local population. Most locals have more stable jobs and higher family monthly incomes than migrants. The locals’ homeownership rate was obviously higher than that of migrants. In terms of the characteristics of residential relocation, the migrants relocated more frequently than the locals in Urumqi. The proportion of migrants’ forced relocation was higher than that of locals. The overall average residential satisfaction of the local population with housing and community was higher than that of migrants.

- (2)

- We revealed the spatial consequences of the different relocation flows and directions between migrants and locals. The common feature of locals and migrants was that their main relocation direction was from southern urban areas, like Tianshan and Saybark Districts, to the northern urban areas, like Xinshi and Midong Districts. This phenomenon contributes to the northward shift of the urban population center. In contrast with the locals whose net migration direction was from the marginal to the central area, the net migration direction of migrants was from the central to the marginal area, which contributed to the concentration of locals and the suburbanization of migrants. The spatial segregation between locals and migrants increased due to the different directions between locals and migrants based on spatial assimilation theory.With regard to the home-moving patterns of migrants and locals, similar to what is depicted by the spatial assimilation theory, migrants had noticeably different housing behaviors from those of locals. The results of the social network analysis indicated that the migration directions of locals and migrants were partly different, which can be regarded as a sign of segregation based on spatial assimilation theory.

- (3)

- Although the locals and migrants live together in Urumqi, the determinants of intentions to move of these two groups were different. As expected, demographic factors, employment factors, family and housing factors, and residential satisfaction were the factors influencing the locals’ relocation intention. The locals’ intentions to move were influenced by age, ethnic group, type of employment, family population, housing area, and residential satisfaction. For residential satisfaction of locals, the satisfaction with convenience of catering and entertainment facilities was most important among all the attributes of housing and community. The type of employment and other demographic factors did not have a significant influence on the mobility intention of migrants. The migrants’ intentions to move were mainly influenced by housing type, satisfaction with housing area and the residential greening of the community.We focused on the residential mobility of locals and migrants in urban areas in Northwest China using comparative analysis. The findings suggest areas of future research relating to both residential mobility itself and to the impact of residential mobility on individuals, communities, urban society, and space. With respect to residential mobility, the patterns of different groups’ relocation and the determinants of decisions to move in urban China need to be recognized. With respect to the impact of residential mobility, future research could consider the interplay between urban social space and residential mobility. A sensitivity analysis of the impact of different groups’ residential mobility on social segregation and spatial differentiation is a possible direction for future research of urban China.

Author Contributions

X.J. and J.L. designed the research; X.J. analyzed the data; X.J. wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 41671168).

Acknowledgments

We owe thanks to Zuliang Duan, Zhen Yang, Jiangang Li and Jinping Li for helping to implement the questionnaire survey which constitutes the database of the present study. We are also grateful to the three anonymous reviewers who provided comments on the paper—the paper is much improved as a result.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zhao, M.; Qi, W.; Liu, S. Spatial differentiation and formation mechanism of floating population communities in Beijing. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2018, 73, 1494–1512. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.F. Counting urban population in Chinese censuses 1953–2000: Changing definitions, problems and solutions. Popul. Space Place 2005, 11, 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Project Team of the Research Institute of the State Council. Survey Report on Peasant Workers in China; Yanshi Press: Beijing, China, 2006. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J. Migration, floating population and urbanization in China: Realities, theories, and strategies. Geogr. Res. 2019, 38, 33–44. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- He, S.; Qi, X. Determinants of Relocation Satisfaction and Relocation Intention in Chinese Cities: An Empirical Investigation on Three Types of Residential Neighborhood in Guangzhou. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2014, 34, 1327–1336. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Yan, X. Comparison of influencing factors for residential mobility between different household register types in transitional urban China: A case study of Guangzhou. Geogr. Res. 2007, 26, 1055–1066. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.M.; Wu, F.L. Contextualizing residential mobility and housing choice: Evidence from urban China. Environ. Plan. A 2004, 36, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Shi, Z.; Song, X.; Deng, W. Space trade-offs analysis in the urban floating population residential self-selection: Acase study of Chengdu. Geogr. Res. 2018, 12, 2554–2566. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Wu, D.; Yang, D. Willingness to move, place dependence and community identity: An investigation of residential choice in the Zhongguancun area in Beijing. Prog. Geogr. 2019, 38, 417–427. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Song, W.; Chen, P.; Hu, Y. A review of research on residential mobility from the perspective of urban geography. Urban Plan. Forum 2015, 5, 45–49. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Xu, X. A summary of research progresson residential mobility in western cities. Hum. Geogr. 1996, 11, 23–27. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Mcleod, P.B.; Ellis, J.R. Housing Consumption Over the Family Life Cycle: An Empirical Analysis. Urban Stud. 1982, 19, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C. Introduction of theoretical studies of migration of urban population. Urban Plan. Forum 1996, 3, 34–40. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chai, Y.; Hu, Z.; Wu, Z. On characteastics and mechanism of intra-urban residents’ migration in Tianjin City, China. Geogr. Res. 2000, 19, 391–399. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Y.; Zhou, S. The character and mechanism of former staff-living community residents migration—A case study in Jiannan Zhong Street, Guangzhou, China. Hum. Geogr. 2010, 25, 36–40. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.M.; Siu, Y.M. Residential mobility and urban restructuring under market transition: A study of Guangzhou, China. Prof. Geogr. 2001, 53, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Chai, Y.; Liu, Z. The time-space analysis of citizen mobility characteristics of Shenzhen city. Hum. Geogr. 2000, 15, 37–42. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C. Analysis on characteristics, Causes and Influential aspects of urban population migration in China. Urban Plan. Forum 1996, 4, 17–21. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J.; Zhou, Y. Intra-urban migration and correlative spatial behavior in Beijing in the process of suburbanization based on 1000 questionnaires. Geogr. Res. 2004, 23, 227–242. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Cheng, H. The spatial characteristics and its impact mechanism of urban residential mobility: Based on micro survey data of Tianjin. Urban Dev. Stud. 2018, 25, 107–115. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chai, Y.; Chen, L. The residential mobility of Urban Danwei Residents: A Life Course Approach. Urban Plan. Int. 2009, 24, 7–14. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, N. Research on the Behavior of the Intra-Urban Migration in Hefei. Master’s Thesis, Anhui Normal University, Hefei, China, 2014. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Gu, J.; Zhou, S.; Yan, X. The space-time paths of residential mobility in Guangzhou from a perspective of life course. Geogr. Res. 2013, 32, 157–165. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.; Cheng, Y. Willingness to relocation of the older people within Beijing. Geogr. Res. 2018, 37, 119–132. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Yan, X.; Cao, X. The spatial characteristics and determinants of intra-urban residential mobility in Guangzhou. Hum. Geogr. 2007, 4, 27–32. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.M. Life course and residential mobility in Beijing, China. Environ. Plan. A-Econ. Space 2004, 36, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.-M.; Wang, D.; Law, F.Y.-T. Residential mobility in a changing housing system: Guangzhou, China, 1980–2001. Urban Geogr. 2005, 26, 627–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Levinson, D.; Wang, J.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Z.J. Tracking job and housing dynamics with smartcard data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 12710–12715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Zhen, F. The impacts of information channels on moving space: A case study on Nanjing. Geogr. Res. 2016, 35, 1846–1856. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Y. Residential satisfaction, moving intention and moving behaviours: A study of redeveloped neighbourhoods in inner-city Beijing. Hous. Stud. 2006, 21, 671–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Chai, Y. The influence of housing mobility of daily life social network of the elderly in Danwei. Hum. Geogr. 2013, 28, 78–84. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chai, H.; Feng, J. Behavior space of suburban residents in Beijing based on family life course. Prog. Geogr. 2016, 35, 1506–1516. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Dupre, M.E.; Ostbye, T.; Vorderstrasse, A.A.; Wu, B. Residential Mobility and Cognitive Function Among Middle-Aged and Older Adults in China. Res. Aging 2019, 41, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, J. The impact of intra-urban residential mobility on residents’ health: A case study in Guangzhou City. Prog. Geogr. 2018, 37, 801–810. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hou, M. A Study on Community Satisfaction of Low-Income Population from the Prospective of Residential Mobility in Beijing. Master’s Thesis, Capital Normal University, Beijing, China, 2014. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Chai, Y.; Zhou, Y. The Characteristics, Mechanisms and Tendency of Suburbanization of Residence in Dalian City. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2000, 20, 121–132. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Yan, X.; Xie, L. Employment and residential mobility and its spatial structure change based on the 3 years’ survey analysis. Geogr. Res. 2012, 31, 1685–1696. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, W.; Feng, T.; Timmermans, H.; Li, H. A gap-theoretical path model of residential satisfaction and intention to move house applied to renovated historical blocks in two Chinese cities. Cities 2017, 71, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Liu, S.; Qi, W. Exploring the differential impacts of urban transit system on the spatial distribution of local and floating population in Beijing. J. Geogr. Sci. 2017, 27, 731–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Liu, S.; Qi, W. Comparison on foreign and domestic migrant communities: Characteristics and effects. City Plan. Rev. 2015, 39, 19–27. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W. Migrant Intra-Urban Residential Mobility in Urban China. Hous. Stud. 2007, 21, 745–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.M.; Zhu, Y. Residential Mobility within Guangzhou City, China, 1990–2010: Local Residents Versus Migrants. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2014, 55, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, E.C.M.; Li, S.M.; Wong, F.K.W.; Yi, Z.; Yu, K.H. Ethnicity, cultural disparity and residential mobility: Empirical analysis of Hong Kong. Habitat Int. 2012, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Lu, D. Structure and Flow Mechanism of the Floating Population in New Towns of Beijing. Urban Dev. Stud. 2012, 19, 16–21. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- You, Z.; Yang, H.; Fu, M. Settlement intention characteristics and determinants in floating populations in Chinese border cities. Sust. Cities Soc. 2018, 39, 476–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P. Research on the Spatial Distribution Characters of Residence Price in Urumqi City. Master’s Thesis, Xinjiang Agricultural University, Urumqi, China, 2014. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.-M.; Mao, S. Exploring residential mobility in Chinese cities: An empirical analysis of Guangzhou. Urban Stud. 2016, 54, 3718–3737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Dong, G.; Zhang, W.; Li, J. Study on the synergy between intra-urban resident’s migration and job change in Beijing. J. Geogr. Sci. 2015, 25, 978–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lopez, E.; Greenlee, A. An ex-ante analysis of housing location choices due to housing displacement: The case of Bristol Place. Appl. Geogr. 2016, 75, 156–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Lei, J. Spatial-temporal distribution characteristics and simulation of popualtion in the main urban area of Urumqi City from 1982 to 2010. J. Univ. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2018, 35, 506–514. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Yan, S.; He, J.; Liu, L. On the social space evolution of Shanghai: In dual dimensions of the Hukou and the occupation. Geogr. Res. 2018, 37, 2236–2248. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ying, C.; Lei, J.; Duan, Z.; Yang, Z. Characteristics of jobs-housing spatial organization in Urumqi City and influencing factors. Prog. Geogr. 2016, 35, 462–475. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shi, T. Research on Facilities Service Ability Equalization of Primary, Secondary and High Schools in Urumqi. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Urumqi, China, 2015. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; He, S.; Webster, C.; Zhang, X. Unravelling residential satisfaction and relocation intention in three urban neighborhood types in Guangzhou, China. Habitat Int. 2019, 85, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M. Analyzing migration decisionmaking: Relationships between residential satisfaction, mobility intentions, and moving behavior. Environ. Plan. A 1998, 30, 1473–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).