A Comparative Study of User Behaviors on Unimproved and Improved Street Spaces in Da Nang, Vietnam

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Theoretical Background and Previous Studies

1.3. Objective and Research Questions

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Da Nang and Street Space Improvement Overview

2.2. Street Sampling

2.3. Outline of Investigation

2.4. Data Processing

2.4.1 User Behavior Findings and Street Environment Division

2.4.2. Statistical Analysis and Comparative Study

3. Results

3.1. User Behavior Finding

3.2. Quantities of User Behavior Units

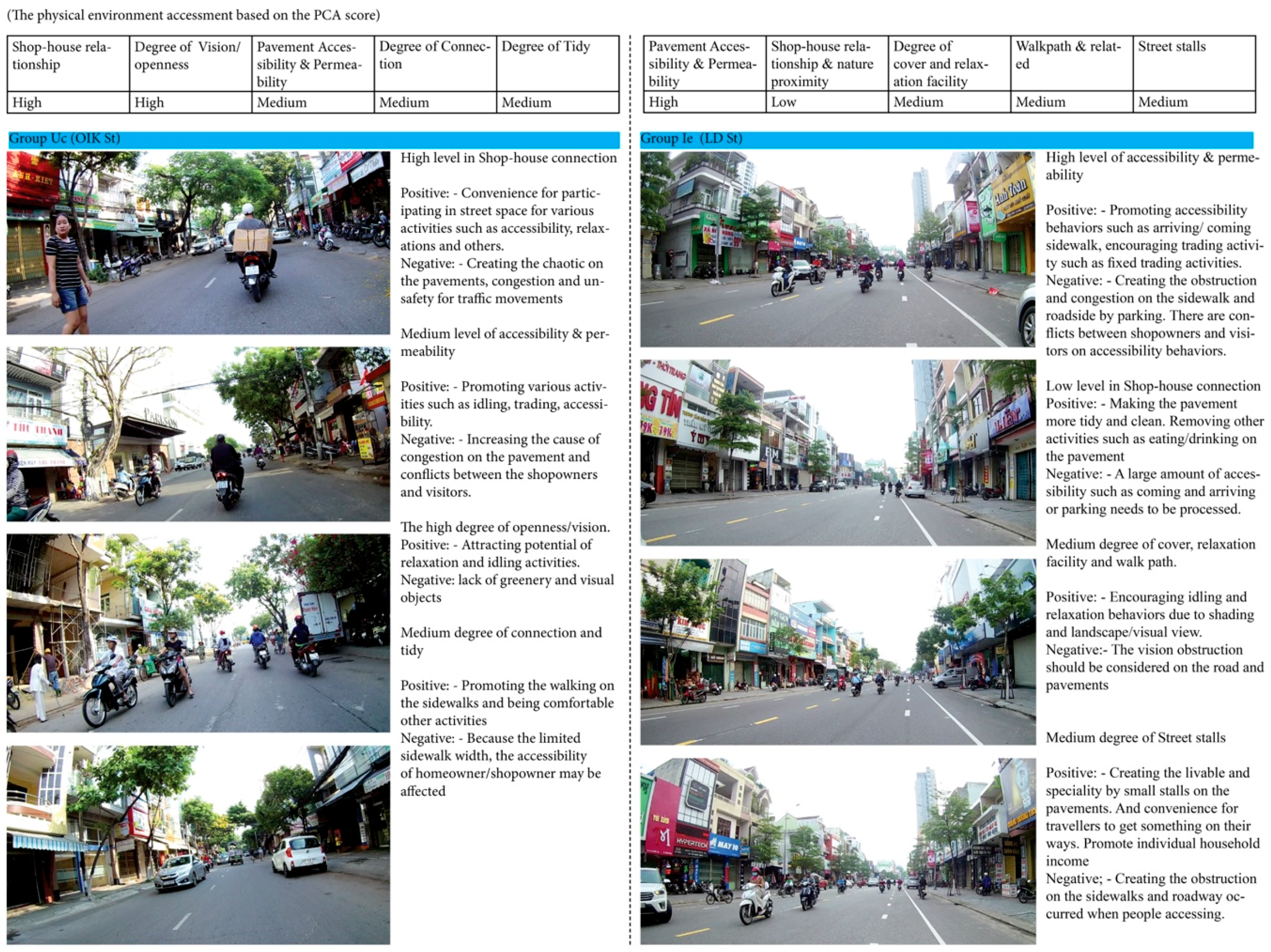

3.3. Environment Characteristics Analysis

3.4. The Correlation between User Behaviors and Street Environment between Two Streets

4. Discussion

4.1. The Difference between Three Environment-Behavior Patterns on Two Kinds of Street

4.1.1. The Environmental Behavior Pattern Attracting the Highest Frequency of User Behaviors (the 1st Pattern)

4.1.2. Environmental Behavior Pattern Discouraging User Behaviors (the 2nd Pattern)

4.1.3. Neutral Environmental Behavior Pattern that Is Neither Frequent nor Infrequent (the 3rd Pattern)

4.1.4. Suggestions for Each Environment-behavior Pattern

5. Further Discussion, The Implication of Street Improvement and Management

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bedimo-Rung, A.L.; Mowen, A.J.; Cohen, D.A. The significance of parks to physical activity and public health: A conceptual model. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2005, 28, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasi, A.; Alalouch, C.; Bramley, G. Open space quality in deprived urban areas: User perspective and use pattern. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 216, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, J.; Wolch, J. Nature, race, and parks: Past research and future directions for geographic research. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2009, 33, 743–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.A.; McKenzie, T.L.; Sehgal, A.; Williamson, S.; Golinelli, D.; Lurie, N. Contribution of public parks to physical activity. Am. J. Public Health 2007, 97, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, H. Linking the quality of public spaces to quality of life. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2009, 2, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, C.A.; Andres, L.; Perera, U.; Roji, A. Enhancing quality of life through the lens of green spaces: A systematic review approach. Int. J. Wellbeing 2016, 6, 142–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consultants, L.U. Making the Links: Greenspace and Quality of Life; Scottish Natural Heritage: Inverness, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bolitzer, B.; Netusil, N.R. The impact of open spaces on property values in Portland, Oregon. J. Environ. Manag. 2000, 59, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, J.; Wolch, J.; Zhang, J. Planning for environmental justice in an urban national park. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2009, 52, 365–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geoghegan, J. The value of open spaces in residential land use. Land Use Policy 2002, 19, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of American Cities; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Donald, A.; Gerson, M.S.; Lintell, M. Livable Streets; University of California Press: Berkely, CA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, M. Urban open spaces. Adv. Environ. Behav. Des. 1987, 1, 71. [Google Scholar]

- Whyte, W.H. The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces; The Conservation Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, J. Making a city: Urbanity, vitality and urban design. J. Urban Des. 1998, 3, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, P. What city? A plea for place in the public realm. Archit. Rev. 1988, 184, 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Faria, P.A.; Ferreira, F.A.; Jalali, M.S.; Bento, P.; António, N.J. Combining cognitive mapping and MCDA for improving quality of life in urban areas. Cities 2018, 78, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Ayllon, S. Urban transformations as indicators of economic change in post-communist Eastern Europe: Territorial diagnosis through five case studies. Habitat Int. 2018, 71, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1960; Volume 11. [Google Scholar]

- Hassen, N.; Kaufman, P. Examining the role of urban street design in enhancing community engagement: A literature review. Health Place 2016, 41, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gehl, J. Life between Buildings: Using Public Space; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona, M.; Heath, T.; Oc, T.; Tiesdell, S. Public Places-Urban Spaces; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, V. Lively streets: Determining environmental characteristics to support social behavior. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2007, 27, 165–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M. London’s local high streets: The problems, potential and complexities of mixed street corridors. Prog. Plan. 2015, 100, 1–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, H. Land use planning and health and well-being. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, S115–S123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, L.B. Street scenes: Practices of public and private space in urban Vietnam. Urban Stud. 2000, 37, 2377–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, P.N. Challenges for sustainable environment in urbanisation in Vietnam. In Proceedings of the Third International Workshop Council Subscription: Natural Resources, Environment and Sustainable Development, Hanoi, Vietnam, 5 December 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Do, T.D.; Mori, S.; Nomura, R. Passenger’s Attention Behaviors along Street Space: A Case Study of Da Nang City. J. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2018, 12, 245–261. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin, K. Defining the ‘field at a given time’. Psychol. Rev. 1943, 50, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, B.; Hanson, J. The Social Logic of Space; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, R.G. Ecological Psychology: Concepts and Methods for Studying the Environment of Human Behavior; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Bechtel, R.B.; Marans, R.W.; Michelson, W.E. Methods in Environmental and Behavioral Research; Van Nostrand Reinhold Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, J. The behavior setting: A unit for Environmental Analysis and Design. Creat. Archit. Theory Role Behav. Sci. Environ. Des. 1987, 113–125. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Brown, G.; Liu, Y.; Mateo-Babiano, I. A comparison of perceived and geographic access to predict urban park use. Cities 2015, 42, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Brown, G.; Zhong, G.; Liu, Y.; Mateo-Babiano, I. Factors influencing perceived access to urban parks: A comparative study of Brisbane (Australia) and Zhongshan (China). Habitat Int. 2015, 50, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Brown, G.; Liu, Y. The physical and non-physical factors that influence perceived access to urban parks. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 133, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.D.; Pham, H.H. Notes on ecological urban development in Vietnam. Vietnam Architecture Magazine, 3 April 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Do, D.; Huang, J.; Cheng, Y.; Truong, T. Da Nang Green Space System Planning: An Ecology Landscape Approach. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, D.T.; Mori, S.; Nomura, R. An Analysis of Relationship between the Environment and User’s Behavior on Unimproved Streets: A Case Study of Da Nang City, Vietnam. Sustainability 2018, 11, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hùng, T. Tái Diễn Lấn Chiếm Vỉa Hè Làm Nơi Buôn Bán; Báo Đà Nẵng: Danang, Vietnam, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Giang, L.A. Kinh tế vỉa hè—Kinh tế đô thị (Pavement Economic—Urban Economic). Vietnam Archit. J. 2016, 200, 23–26. Available online: http://kientrucvietnam.org.vn/paper/tap-chi-ktvn-so-200-2016/ (accessed on 23 December 2018).

- Loan, P.T. Đường phố—Hè phố: Cơ sở khoa học cho nghiên cứu thiết kế đô thị. Archit. J. Vietnam 2016, 200. [Google Scholar]

- Nhi, L.T.H. vỉa hè, không gian của cộng đồng (Pavement-community space). Vietnam Archit. J. 2017, 6, 58–61. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, C.; Kuhnen, A.; Felippe, M.L.; Silveira, B.B. Place-Centered or Person-Centered? Considerations about the Behavioral Mapping Approach. Trends Psychol. 2018, 26, 593–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, H.W.; Christman, S.P. Field techniques for herpetofaunal community analysis. Herpetol. Communities 1982, 13, 193–200. [Google Scholar]

- Da Nang People’s Committee. Location and Natural Conditions. 2018. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20181009042731/https://danang.gov.vn/web/en/detail?id=26029&_c=16407111 (accessed on 10 June 2019).

- Vietnam Institute for Building Science and Technology. Vietnam Building Code Natural Physical & Climatic Data for Construction; Vietnam Institute for Building Science and Technology: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2009; pp. 188–192. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, E.T. Proxemics: The Study of Man’s Spatial Relations; International Universities Press: New York, NY, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Heft, H. Ecological Psychology in Context: James Gibson, Roger Barker, and the Legacy of William James’s Radical Empiricism; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Schoggen, P. Behavior Settings: A Revision and Extension of Roger G. Barker’s Ecological Psychology; Stanford University Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Jolliffe, I. Principal Component Analysis; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, P.J. Multivariate Statistics for the Environmental Sciences; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Eisen, M.B.; Spellman, P.T.; Brown, P.O.; Botstein, D. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 14863–14868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredline, E.; Faulkner, B. Host community reactions: A cluster analysis. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 763–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehaffy, M.W.; Porta, S.; Romice, O. The “neighborhood unit” on trial: A case study in the impacts of urban morphology. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2015, 8, 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, C. A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, C. The Nature of Order: The Phenomenon of Life; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, C. The Nature of Order: The Process of Creating Life; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, S.A.; Guide, R.; Schmid, T.L.; Moore, L.V.; Barradas, D.T.; Fulton, J.E. Public support for street-scale urban design practices and policies to increase physical activity. J. Phys. Act. Health 2011, 8, S125–S134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateo-Babiano, I.B.; Ieda, H. Street space sustainability in Asia: The role of the Asian pedestrian and street culture. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference of Eastern Asia Society for Transportation Studies, Beijing, China, 9–13 October 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Munemoto, J.; Yoshida, T. Analysis of Behaviors along the Waterside in a Chinese Residential Quarter. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2011, 10, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pánek, J.; Benediktsson, K. Emotional mapping and its participatory potential: Opinions about cycling conditions in Reykjavík, Iceland. Cities 2017, 61, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Rhodes, J.; Dade, M. An evaluation of participatory mapping methods to assess urban park benefits. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 178, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Street Name | Ong Ich Khiem | Le Duan |

|---|---|---|

| Street Type | Collector Streets | Collector Streets |

| Street Classification | Unimproved | Improved (launch in 1998) |

| Length | 2.22 km | 2.17 km |

| District | Hai Chau | Hai Chau |

| Width | 10.5 m | 15 m |

| Pavement Width | 1–4 m | 4–6 m |

| Landuse along the street | Residences, Commercial Buildings, Greenspace, Markets, School, Shop house, Administration Agency, Public building | Residences, Commercial Buildings, Greenspace, Markets, School, Shop house, Administration Agency, Public building |

| Setback | 1.2 m | 1.2 m |

| Behavioral Category | Specific Behaviors | Behavior Frequency in Ong Ich Khiem St | Behavior Frequency in Tran Phu St | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accessibility | crossing road | 62 | 63 | 125 |

| leaving/coming with motorcycle | 421 | 549 | 970 | |

| leaving/coming without motorcycle | 146 | 173 | 319 | |

| walking for destination | 204 | 209 | 413 | |

| Trading | food transaction fixed | 66 | 5 | 71 |

| goods transaction fixed | 25 | 11 | 36 | |

| food transaction mobility | 78 | 17 | 95 | |

| goods transaction mobility | 51 | 35 | 86 | |

| Idling | waiting for crossing road | 46 | 23 | 69 |

| waiting for others | 225 | 150 | 375 | |

| waiting for the bus | 4 | 25 | 29 | |

| waiting for customers | 70 | 36 | 106 | |

| Service/ Maintenance | cleaning | 73 | 50 | 123 |

| commercial preparation | 57 | 26 | 83 | |

| guarding | 46 | 196 | 242 | |

| public maintenance | 20 | 14 | 34 | |

| repairing | 51 | 26 | 77 | |

| Relaxation | playing | 21 | 27 | 48 |

| reading | 75 | 67 | 142 | |

| strolling | 72 | 86 | 158 | |

| looking others | 210 | 180 | 390 | |

| resting | 29 | 39 | 68 | |

| chatting | 50 | 66 | 116 | |

| Others | eating | 89 | 21 | 110 |

| inquiring | 76 | 47 | 123 | |

| drinking | 122 | 36 | 158 |

| Section | Commercial/Private Component | Public Component | Street Functions Component | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retail + Service | Food Spots | Recreational Facilities | Offices/Public Agency | Vacancies | Greenspace | Residence | Sidewalk | Amenities | Obstructions | Landscape | Width | Signs | Transportation | ||||||||||||||

| Width > 6m (Ld); > 4m (Oik) * | Curb Cuts | Bench | Trash Cans | Fence | Electric Poles/Infra. | Sign Poles | Motorcycle Parking Line | Trees | Awning | Balcony | Setback > 1.2 m * | >15m (Ld st); > 10.5 m (Oik st) * | Official Signs | Unofficial Signs | Store Sign | Bus Stop | Car Parking Area | Crossing Lane | |||||||||

| Ong ich khiem Street | A1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| B1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | |

| B14 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| A15 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Le duan Street | C1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| D1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | |

| D9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| C10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| * according to Da Nang Urban Planning Institute. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Component | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axis 1 | Axis 2 | Axis 3 | Axis 4 | Axis 5 | |

| Store sign | 00.959 | 0.003 | 0.036 | −0.012 | 0.117 |

| Retail service | 00.959 | 0.003 | 0.036 | −0.012 | 0.117 |

| Residence | 00.818 | 0.159 | −0.051 | −0.076 | −0.337 |

| Awning | 00.747 | 0.084 | 0.042 | −0.246 | 0.169 |

| Balcony | 00.324 | 0.843 | 0.100 | −0.244 | 0.051 |

| Greenspace | 00.114 | −0.840 | −0.266 | 0.164 | 0.138 |

| Vacancies | −00.246 | −0.800 | −0.233 | −0.280 | 0.166 |

| Official signs | −00.113 | 0.589 | −0.314 | 0.019 | 0.129 |

| Public agency | 00.169 | −0.059 | 0.840 | −0.065 | 0.058 |

| Setback | −00.231 | 0.086 | 0.797 | 0.014 | −0.067 |

| Bus stop | 00.085 | 0.319 | 0.618 | −0.155 | −0.048 |

| Street width | −00.095 | −0.121 | 0.076 | 0.860 | −0.005 |

| Crossing/ pedestrian way | −00.151 | 0.040 | −0.358 | 0.785 | 0.137 |

| Trash cans | −00.039 | 0.055 | −0.238 | 0.001 | 0.864 |

| Unofficial signs | 00.280 | −0.158 | 0.297 | 0.130 | 0.628 |

| Eigenvalue | 3.954 | 2.671 | 1.972 | 1.478 | 1.254 |

| Variance % | 26.361 | 17.810 | 13.146 | 9.850 | 8.363 |

| Cumulative % | 26.361 | 44.170 | 57.316 | 67.166 | 75.529 |

| Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis. Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization. | |||||

| a. Rotation converged in 6 iterations. | |||||

| Component | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axis 1 | Axis 2 | Axis 3 | Axis 4 | Axis 5 | |

| Setback | 0.834 | −0.178 | 0.083 | −0.135 | −0.060 |

| Fence | 0.798 | 0.003 | 0.033 | 0.181 | −0.041 |

| Sign poles | 0.685 | −0.039 | 0.047 | −0.373 | 0.330 |

| Public agency | 0.555 | −0.450 | 0.238 | 0.398 | 0.084 |

| Retail service | −0.006 | 0.860 | 0.204 | −0.049 | 0.139 |

| Residence | −0.173 | 0.844 | −0.052 | 0.248 | −0.005 |

| Greenspace | 0.167 | −0.531 | 0.116 | −0.495 | −0.273 |

| Trees | −0.040 | −0.148 | 0.849 | 0.057 | 0.174 |

| Bus stop | 0.173 | 0.181 | 0.812 | 0.064 | −0.096 |

| Recreational facilities | 0.106 | 0.083 | 0.582 | −0.476 | 0.051 |

| Sidewalk | 0.053 | 0.182 | 0.051 | 0.881 | 0.064 |

| Food spots | 0.239 | 0.186 | 0.023 | −0.127 | 0.815 |

| Awning | −0.147 | 0.008 | 0.079 | 0.240 | 0.789 |

| Eigenvalue | 3.009 | 2.318 | 1.656 | 1.376 | 1.173 |

| Variance % | 23.149 | 17.833 | 12.739 | 10.585 | 9.024 |

| Cumulative % | 23.149 | 40.982 | 53.721 | 64.306 | 73.330 |

| Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis. Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization. | |||||

| a. Rotation converged in 6 iterations. | |||||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Do, D.T.; Mori, S.; Nomura, R. A Comparative Study of User Behaviors on Unimproved and Improved Street Spaces in Da Nang, Vietnam. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3457. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123457

Do DT, Mori S, Nomura R. A Comparative Study of User Behaviors on Unimproved and Improved Street Spaces in Da Nang, Vietnam. Sustainability. 2019; 11(12):3457. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123457

Chicago/Turabian StyleDo, Duy Thinh, Suguru Mori, and Rie Nomura. 2019. "A Comparative Study of User Behaviors on Unimproved and Improved Street Spaces in Da Nang, Vietnam" Sustainability 11, no. 12: 3457. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123457

APA StyleDo, D. T., Mori, S., & Nomura, R. (2019). A Comparative Study of User Behaviors on Unimproved and Improved Street Spaces in Da Nang, Vietnam. Sustainability, 11(12), 3457. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123457