The Role of Relationships at Work and Happiness: A Moderated Moderated Mediation Study of New Zealand Managers

Abstract

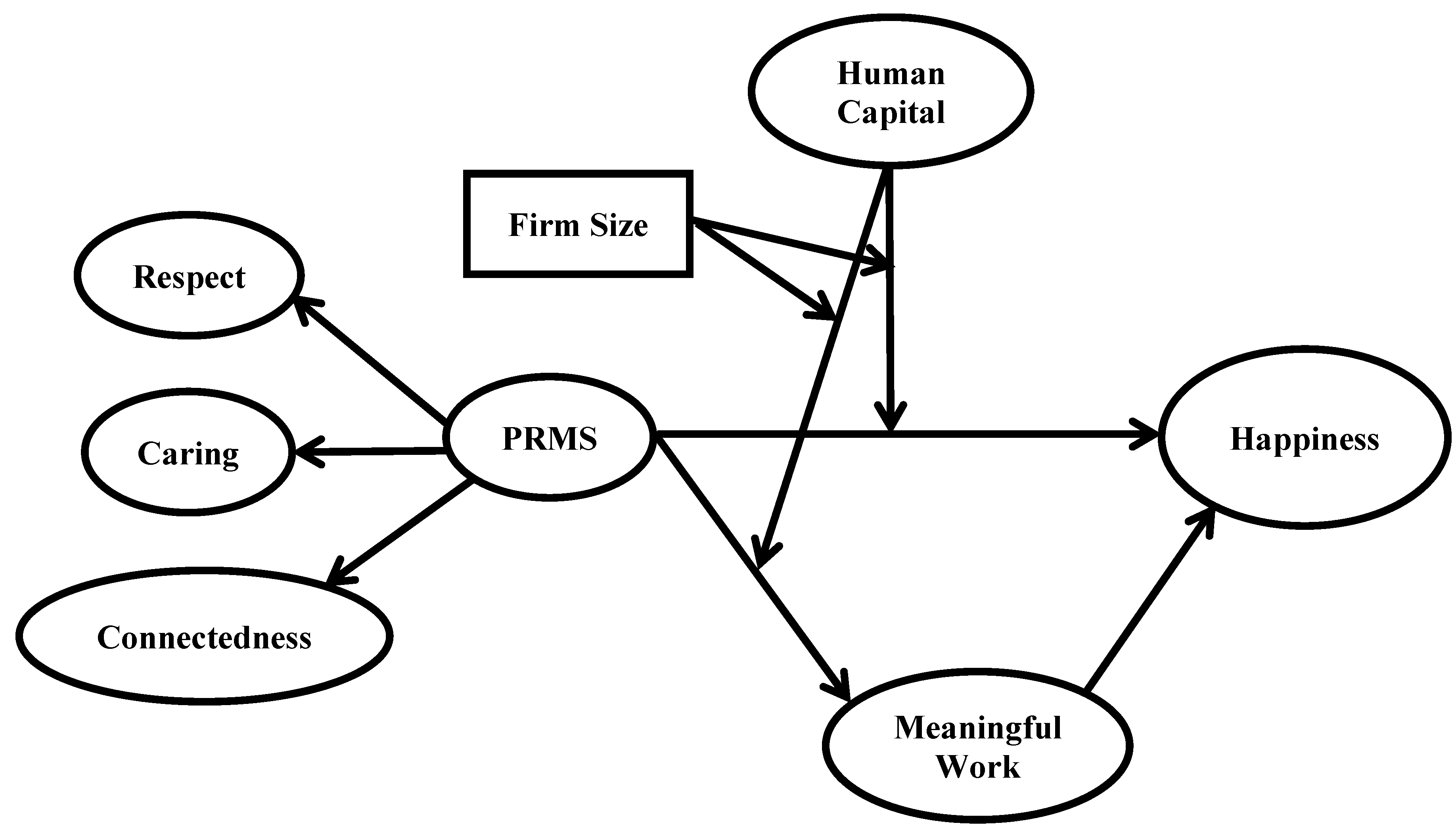

1. Introduction

2. Happiness

3. Positive Relational Management

4. Meaningful Work

5. Firm Level Moderators

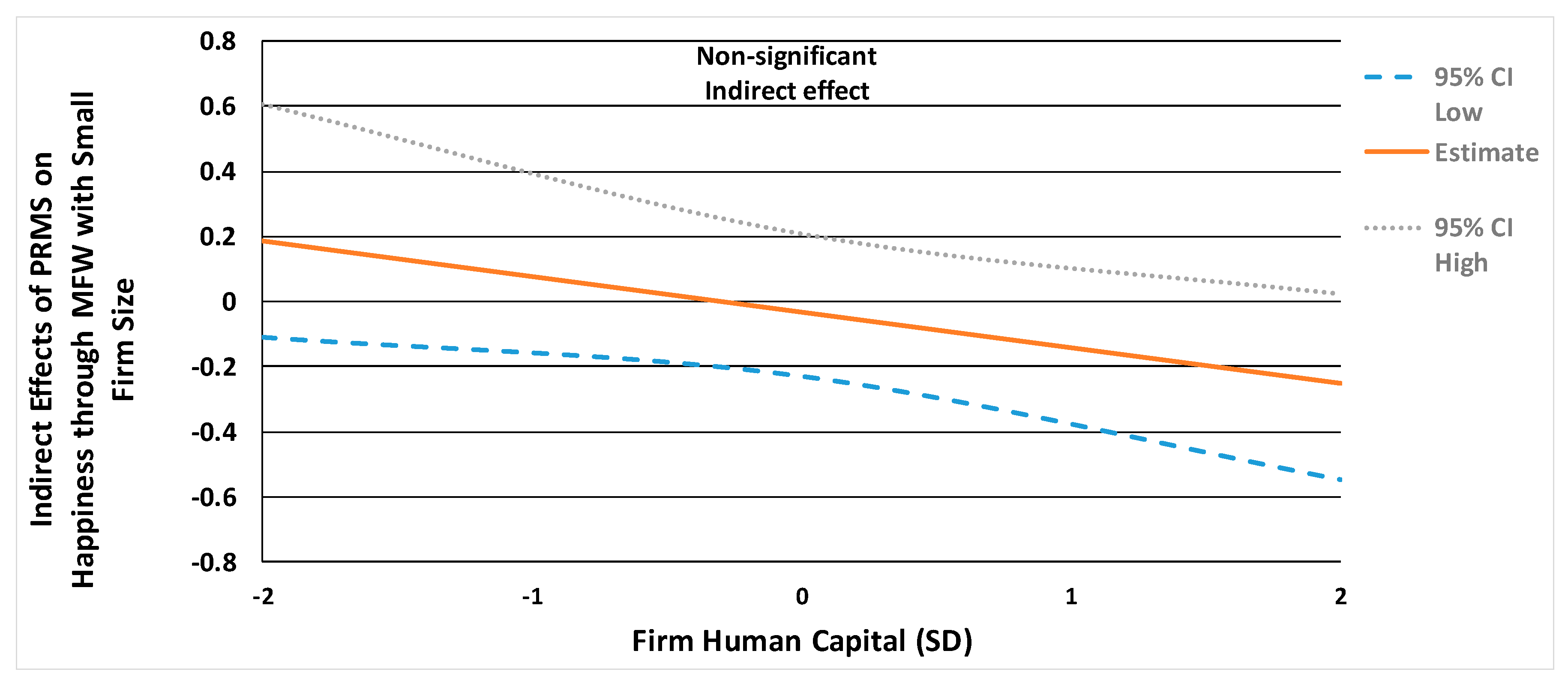

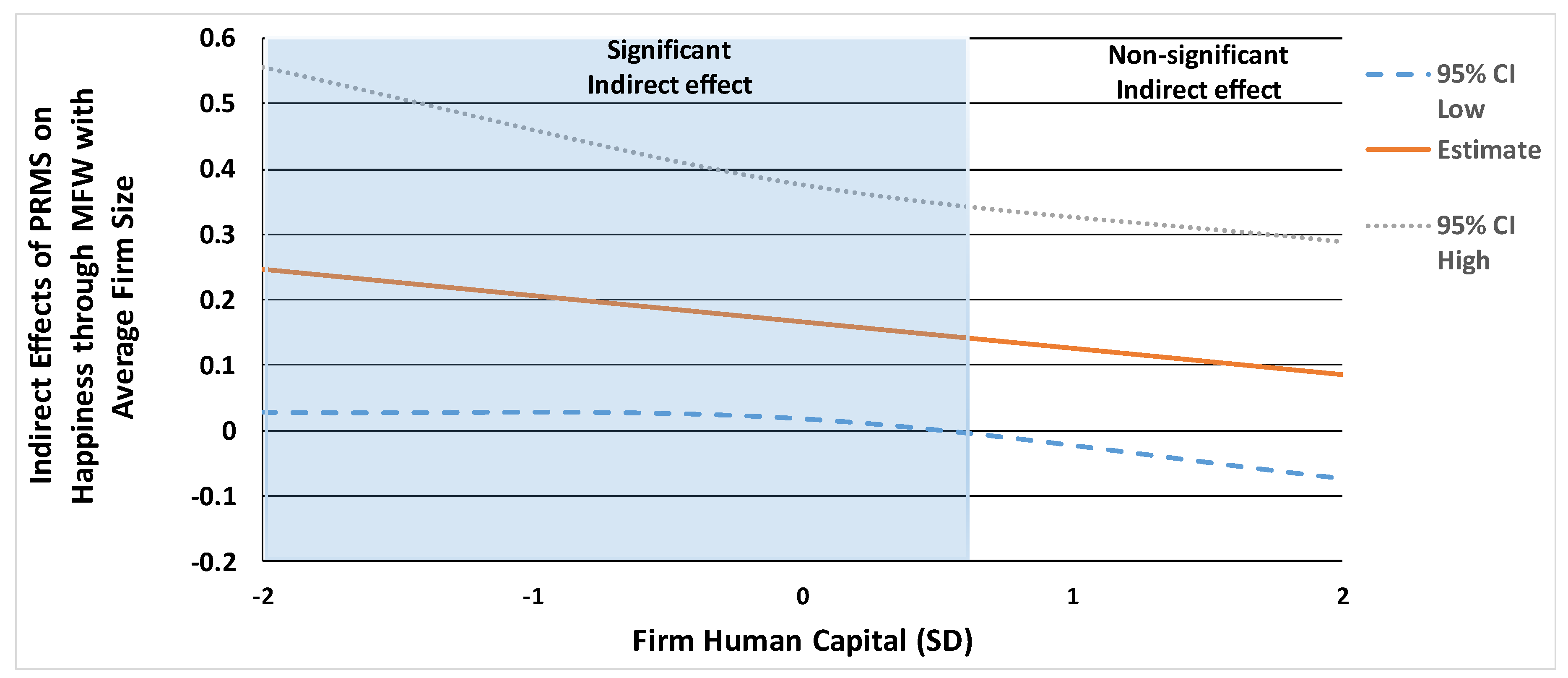

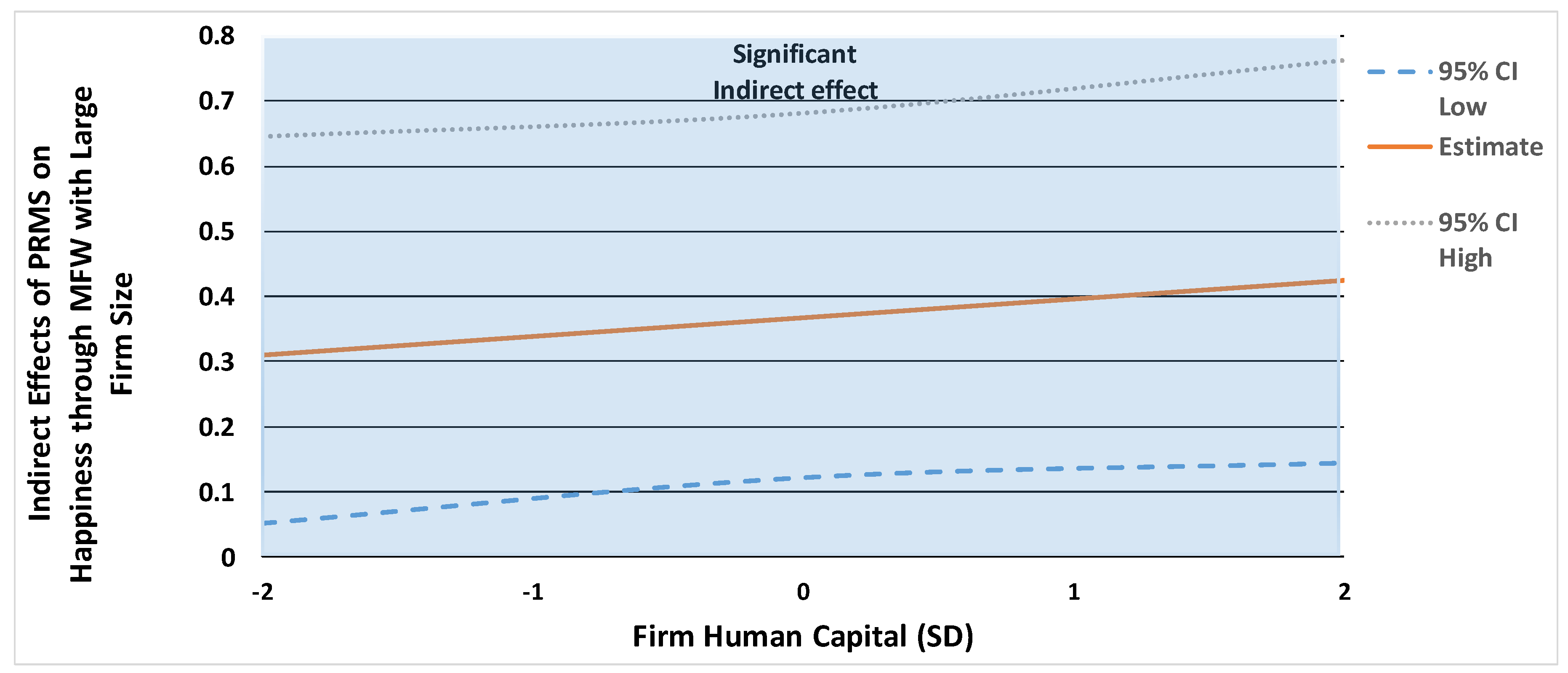

5.1. Human Capital

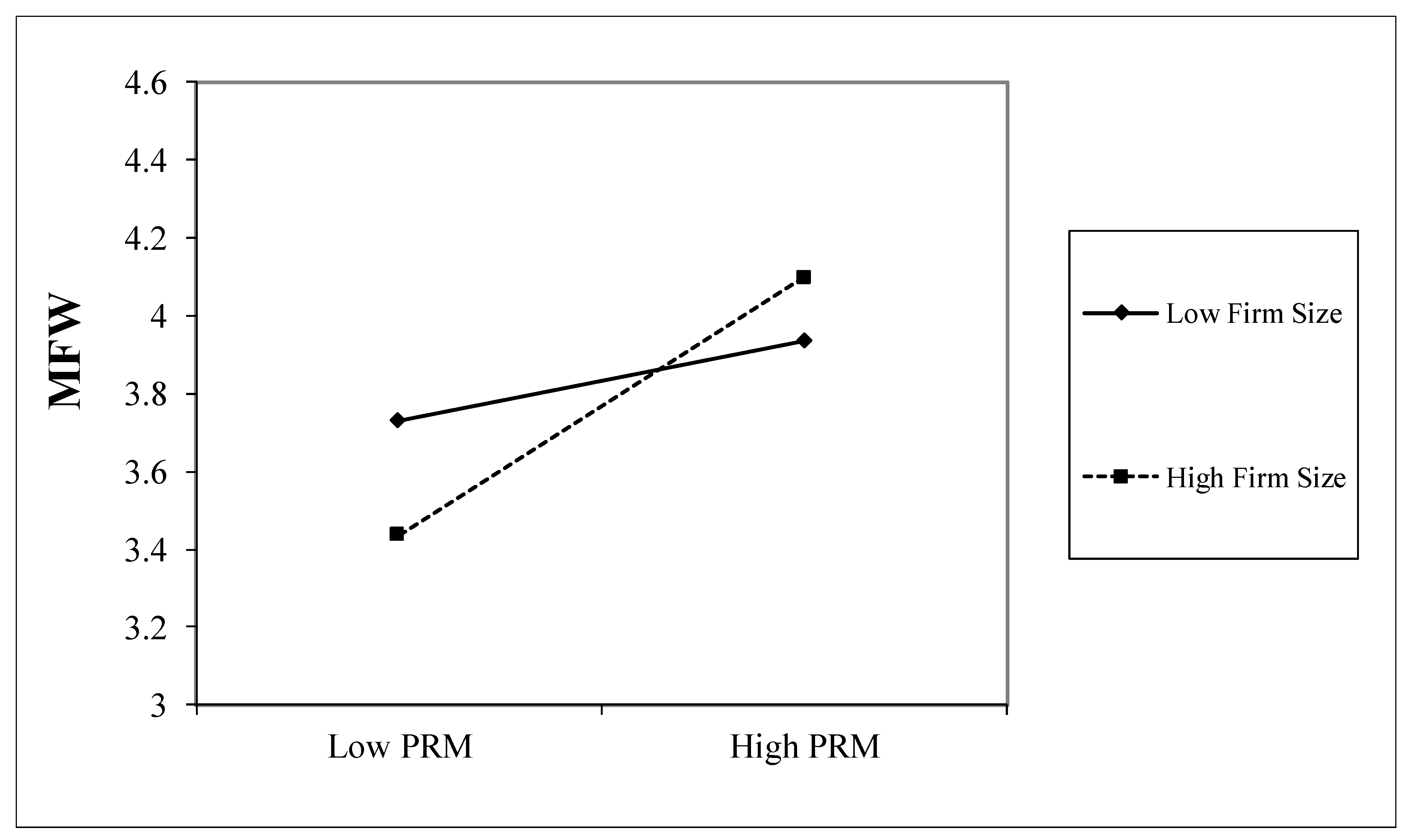

5.2. Firm Size

6. Methods

6.1. Participants and Sample

6.2. Measures

6.3. Measurement Models.

6.4. Analysis

7. Results

8. Discussion

8.1. Implications and Future Research

8.2. Limitations

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Di Fabio, A. The psychology of sustainability and sustainable development for well-being in organizations. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Fabio, A. Positive Healthy Organizations: Promoting well-being, meaningfulness, and sustainability in organizations. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, C.D. Happiness at work. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 384–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, M.; Haar, J.M.; Luthans, F. Mindfulness, psychological capital and leader wellbeing. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2014, 19, 476–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ten Brummelhuis, L.L.; Haar, J.; Roche, M. Does family life help to be a better leader? A closer look at cross-over processes from leaders to followers. Pers. Psychol. 2014, 67, 917–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Positive Psychology: An Introduction; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabio, A. Positive relational management for healthy organizations: Psychometric properties of a new scale for prevention for workers. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A.; Saklofske, D.H. Positive relational management for sustainable development: Beyond personality traits—The contribution of emotional intelligence. Sustainability 2019, 11, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A.; Kenny, M.E. Resources for enhancing employee and organizational well-being beyond personality traits: The promise of Emotional Intelligence and Positive Relational Management. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Commun. Monogr. 2018, 85, 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treasury New Zealand. The Wellbeing Budget 30 May 2019; Treasury New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand, 2019.

- Cooper, C.L. The happiness agenda. Stress Health 2010, 26, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Waal, A. Increasing organisational attractiveness. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2018, 5, 124–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubomirsky, S.; King, L.; Diener, E. The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychol. Bull. 2005, 131, 803–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.B.; Oerlemans, W. Subjective well-being in organizations. In The Oxford Handbook of Positive Organizational Scholarship; Cameron, K.S., Spreitzer, G.M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 178–189. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Sandvik, E.; Pavot, W. Happiness is the frequency, not the intensity, of positive versus negative affect. In Subjective Well-Being: An Interdisciplinary Perspective; Strack, F., Argyle, M., Schwarz, N., Eds.; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1991; pp. 119–139. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Oerlemans, W.; Sonnentag, S. Workaholism and daily recovery: A day reconstruction study of leisure activities. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Shimazu, A.; Bakker, A.B.; Shimada, K.; Kawakami, N. Work-self balance: A longitudinal study on the effects of job demands and resources on personal functioning in Japanese working parents. Work Stress 2013, 27, 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isen, A.M. Success, failure, attention and reaction to others: The warm glow of success. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1970, 15, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, M.R. Does happiness mean friendliness? Induced mood and heterosexual self-disclosure. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 14, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, M.R. What do you do when you’re happy or blue? Mood, expectancies, and behavioral interest. Motiv. Emot. 1988, 12, 309–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenhoven, R. The utility of happiness. Soc. Indic. Res. 1988, 20, 333–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Leary, M.R. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 497–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A. Career counselling and positive psychology in the 21st century: New constructs and measures for evaluating the effectiveness of intervention. J. Couns. 2014, 1, 193–213. [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabio, A.; Kenny, M.E. From decent work to decent lives: Positive self and relational management (PS & RM) in the twenty-first century. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 361. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Di Fabio, A. Positive Relational Management Scale to detect positivity and complexity. Counseling. Ital. J. Res. Appl. 2015, 8, 112–125. [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabio, A.; Bucci, O. Affective profiles in Italian high school students: Life satisfaction, psychological well-being, self-esteem, and optimism. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobfoll, S.E. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 2001, 50, 337–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of Resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnoux-Nicolas, C.; Sovet, L.; Lhotellier, L.; Di Fabio, A.; Bernaud, J.-L. Perceived work conditions and turnover intentions: The mediating role of meaning of life and meaning of work. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, J.E. Energize Your Workplace: How to Create and Sustain High-Quality Connections at Work; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton, J.E.; Ragins, B.R. Exploring Positive Relationships at Work; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rath, T. Vital Friends: The People You Can’t Afford to Live Without; Gallup Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Spreitzer, G.M. Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 1442–1465. [Google Scholar]

- Tummers, L.G.; Knies, E. Leadership and meaningful work in the public sector. Public Adm. Rev. 2013, 73, 859–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.M.; Kizilos, M.; Nason, S. A dimensional analysis of the relationship between psychological empowerment and effectiveness, satisfaction, and strain. J. Manag. 1997, 23, 679–704. [Google Scholar]

- Steger, M.F.; Dik, B.J.; Duffy, R.D. Measuring meaningful work: The work and meaning inventory (WAMI). J. Career Assess. 2012, 20, 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Rao, M.K. Effect of intellectual capital on dynamic capabilities. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2016, 29, 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Schuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, L.C.; Wang, C.H. Clarifying the effect of intellectual capital on performance: The mediating role of dynamic capability. Br. J. Manag. 2012, 23, 179–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakhli, M.; De Clercq, D. Human capital, social capital, and innovation: A multi-country study. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2004, 16, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youndt, M.A.; Snell, S.A. Human resource configurations, intellectual capital, and organizational performance. J. Manag. Issues 2004, 16, 337–360. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment. Small Businesses in New Zealand: How Do They Compare with Larger Firms; MBIE: Wellington, New Zealand, 2017.

- Haar, J.; White, B. Corporate entrepreneurship and employee retention in New Zealand: The moderating effects of information technology. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2013, 23, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, J.; Haar, J. Risk taking, innovativeness and competitive rivalry: A three-way interaction towards firm performance. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2010, 14, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haar, J.; Taylor, A.; Wilson, K. Owner passion, entrepreneurial culture, and financial performance: A study of New Zealand entrepreneurs. N. Z. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 2009, 7, 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Haar, J.M.; Spell, C.S. Factors affecting employer adoption of drug testing in New Zealand. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2007, 45, 200–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haar, J.M.; Spell, C.S. Predicting total quality management in New Zealand: The moderating effect of organizational size. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2008, 21, 162–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haar, J.; Carr, S.; Parker, J.; Arrowsmith, J.; Hodgetts, D. Alefaio-Tugia, S. Escape from working poverty: Steps toward sustainable livelihood. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegall, M.; Gardner, S. Contextual factors of psychological empowerment. Pers. Rev. 2000, 29, 703–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.C.; Lin, C.Y.Y. Does intellectual capital mediate the relationship between HRM and organizational performance? Perspective of a healthcare industry in Taiwan. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2009, 20, 1965–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W.; Feldman, D.C. The relationships of age with job attitudes: A meta-analysis. Pers. Psychol. 2010, 63, 677–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.J.; Vandenberg, R.J.; Edwards, J.R. 12 Structural equation modeling in management research: A guide for improved analysis. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2009, 3, 543–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Analyses, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wayne, S.J.; Lemmon, G.; Hoobler, J.M.; Cheung, G.W.; Wilson, M.S. The ripple effect: A spillover model of the detrimental impact of work–family conflict on job success. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 876–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnavita, N. Productive aging, work engagement and participation of older workers. A triadic approach to health and safety in the workplace. Epidemiol. Biostat. Public Health 2017, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Oerlemans, W.G. Momentary work happiness as a function of enduring burnout and work engagement. J. Psychol. 2016, 150, 755–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harolds, J.A. Quality and safety in health care, Part L: Positive psychology and burnout. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, M.S.; Garza, A.S.; Slaughter, J.E. Work engagement: A quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 89–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böckerman, P.; Ilmakunnas, P. The job satisfaction-productivity nexus: A study using matched survey and register data. Ind. Labor Relat. Rev. 2012, 65, 244–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosey, D. Are happy employees healthy employees? Researching the effects of employee engagement on absenteeism. Can. Public Adm. 2010, 53, 551–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blustein, D.L. The Psychology of Working: A New Perspective for Counseling, Career Development, and Public Policy; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahway, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Blustein, D.L. A relational theory of working. J. Vocat. Behav. 2011, 79, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A.; Kenny, M.E. Decent work in Italy: Context, conceptualization, and assessment. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 110, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blustein, D.L.; Kenny, M.E.; Di Fabio, A.; Guichard, J. Expanding the impact of the psychology of working: Engaging psychology in the struggle for decent work and human rights. J. Career Assess. 2019, 27, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, B.A.; Batz-Barbarich, C.; Sterling, H.M.; Tay, L. Outcomes of meaningful work: A meta-analysis. J. Manag. Stud. 2019, 56, 500–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogelberg, S.G. Why your meetings stink-and what to do about IT Strategies for engagement. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2019, 97, 140–143. [Google Scholar]

- Shore, L.M.; Randel, A.E.; Chung, B.G.; Dean, M.A.; Ehrhart, K.E.; Singh, G. Inclusion and diversity in work groups: A review and model for future research. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1262–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haar, J.M.; Russo, M.; Sune, A.; Ollier-Malaterre, A. Outcomes of work-life balance on job satisfaction, life satisfaction and mental health: A study across seven cultures. J. Vocat. Behav. 2014, 85, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M. A Monte Carlo study of the effects of correlated method variance in moderated multiple regression analysis. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1985, 36, 305–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Montoya, A.K.; Rockwood, N.J. The analysis of mechanisms and their contingencies: PROCESS versus structural equation modeling. AMJ 2017, 25, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being. Psychol. Bull. 1984, 95, 542–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanous, J.P.; Reichers, A.E.; Hudy, M.J. Overall job satisfaction: How good are single-item measures? J. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 82, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Khalek, A.M. Measuring happiness with a single-item scale. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2006, 34, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, N.; Joseph, S. Big 5 correlates of three measures of subjective well-being. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2003, 34, 723–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model Fit Indices | Model Differences | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | χ2 | df | CFI | RMSEA | SRMR | Δχ2 | Δdf | p | Details |

| Model 1 | 143.1 | 90 | 0.97 | 0.04 | 0.04 | ||||

| Model 2 | 194.2 | 95 | 0.95 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 51.1 | 5 | 0.001 | Model 2 to 1 |

| Model 3 | 183.0 | 95 | 0.96 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 39.9 | 4 | 0.001 | Model 3 to 1 |

| Model 4 | 194.1 | 95 | 0.95 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 51.0 | 4 | 0.001 | Model 4 to 1 |

| Model 5 | 230.0 | 99 | 0.93 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 86.9 | 9 | 0.001 | Model 5 to 1 |

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 42.7 | 12.8 | -- | |||||||

| 2. Education | 2.7 | 0.94 | −0.18 ** | -- | ||||||

| 3. Job Tenure | 8.7 | 6.2 | 0.50 ** | −0.07 | -- | |||||

| 4. PRMS | 3.9 | 0.60 | 0.04 | –0.08 | 0.05 | -- | ||||

| 5. MFW | 3.8 | 0.82 | 0.19 ** | –0.06 | 0.01 | 0.34 ** | -- | |||

| 6. Human Capital | 3.6 | 0.75 | –0.03 | 0.06 | –0.00 | 0.46 ** | 0.40 ** | -- | ||

| 7. Firm Size | 3.4 | 2.3 | –0.38 ** | 0.18** | –0.23 ** | –0.10 | –0.17 ** | –0.08 | -- | |

| 8. Happiness | 7.0 | 2.2 | 0.18 ** | –0.10 | 0.01 | 0.21 ** | 0.37 ** | 0.24 ** | –0.15 ** | -- |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haar, J.; Schmitz, A.; Di Fabio, A.; Daellenbach, U. The Role of Relationships at Work and Happiness: A Moderated Moderated Mediation Study of New Zealand Managers. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3443. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123443

Haar J, Schmitz A, Di Fabio A, Daellenbach U. The Role of Relationships at Work and Happiness: A Moderated Moderated Mediation Study of New Zealand Managers. Sustainability. 2019; 11(12):3443. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123443

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaar, Jarrod, Anja Schmitz, Annamaria Di Fabio, and Urs Daellenbach. 2019. "The Role of Relationships at Work and Happiness: A Moderated Moderated Mediation Study of New Zealand Managers" Sustainability 11, no. 12: 3443. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123443

APA StyleHaar, J., Schmitz, A., Di Fabio, A., & Daellenbach, U. (2019). The Role of Relationships at Work and Happiness: A Moderated Moderated Mediation Study of New Zealand Managers. Sustainability, 11(12), 3443. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123443