Exploring Coordinative Mechanisms for Environmental Governance in Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area: An Ecology of Games Framework

Abstract

:1. Introduction

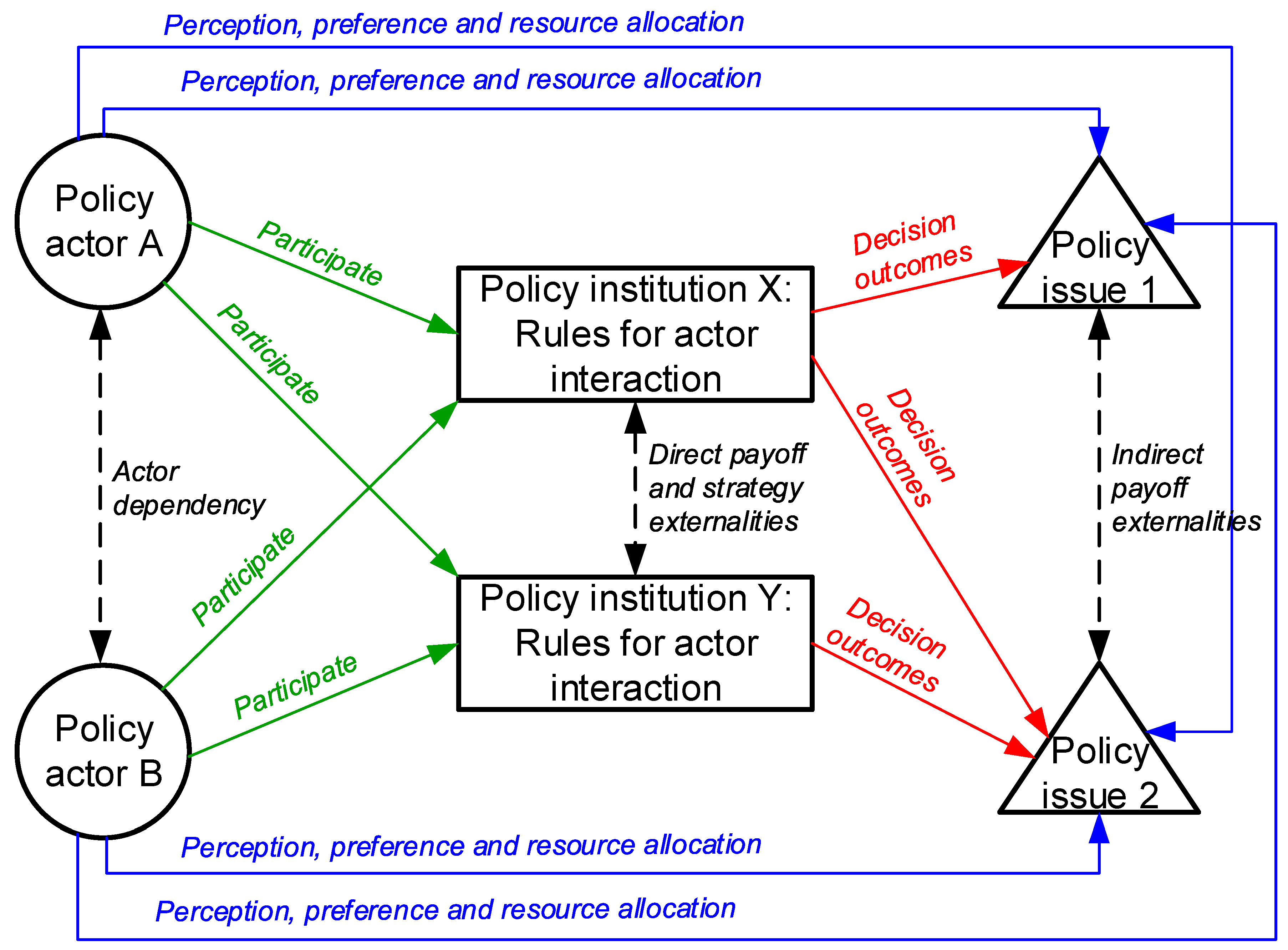

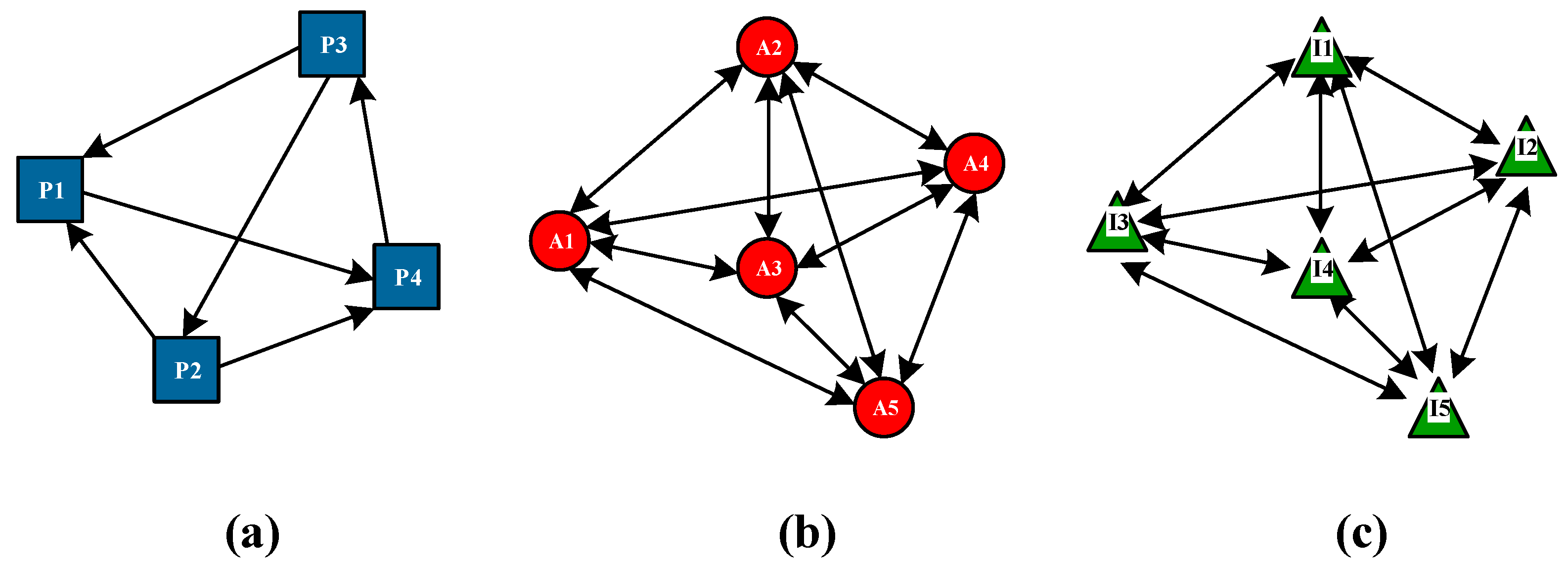

2. The Ecology of Games Framework

2.1. Structural Elements in the EGF

2.2. Coordinative Functions in the EGF

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Case Introduction

3.2. Research Design and Methods

3.3. Data Collection

4. Empirical Findings

4.1. Introduction on the Policy Institutions in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao GBA

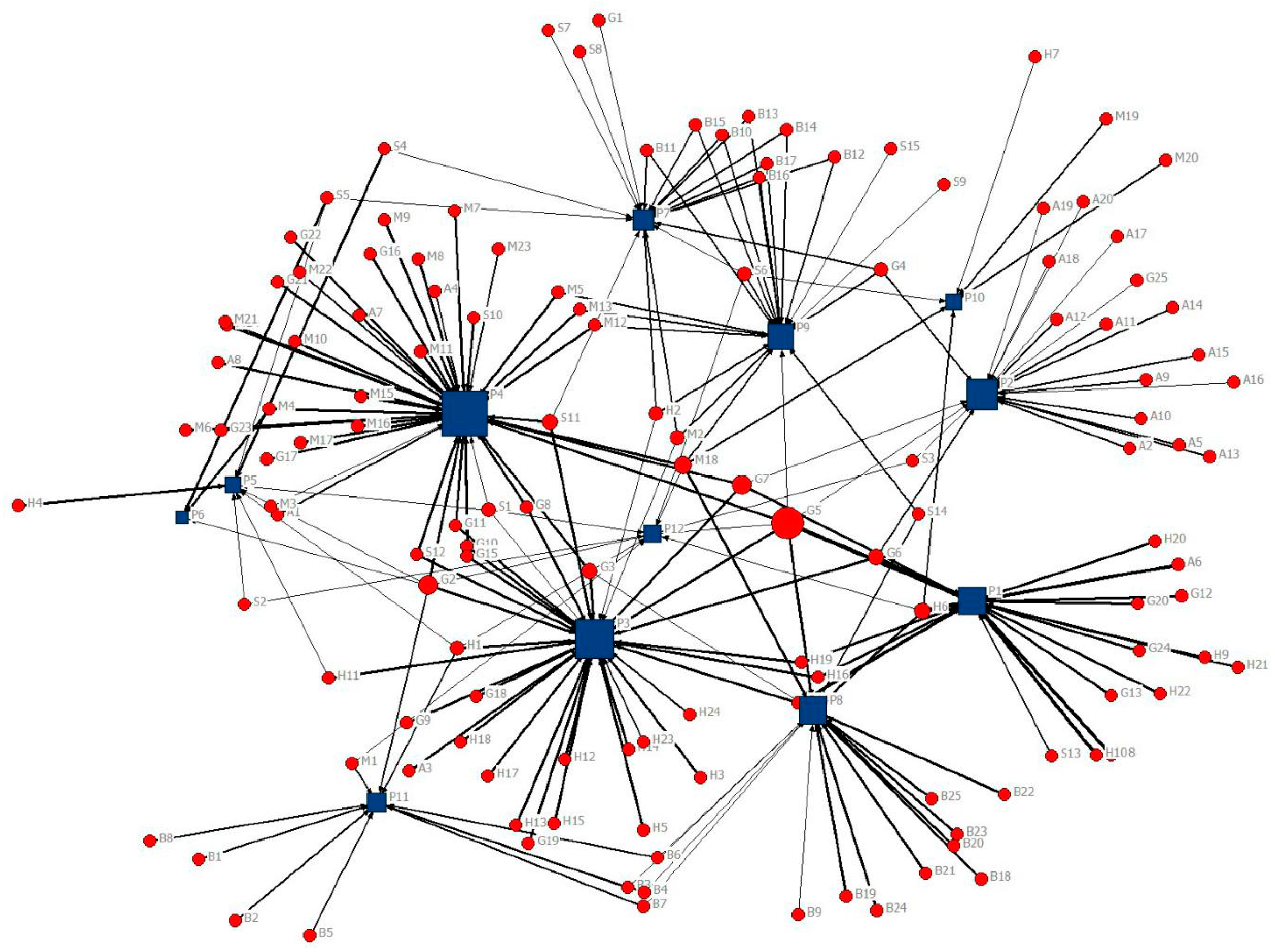

4.2. Actor Participation in Policy Institutions

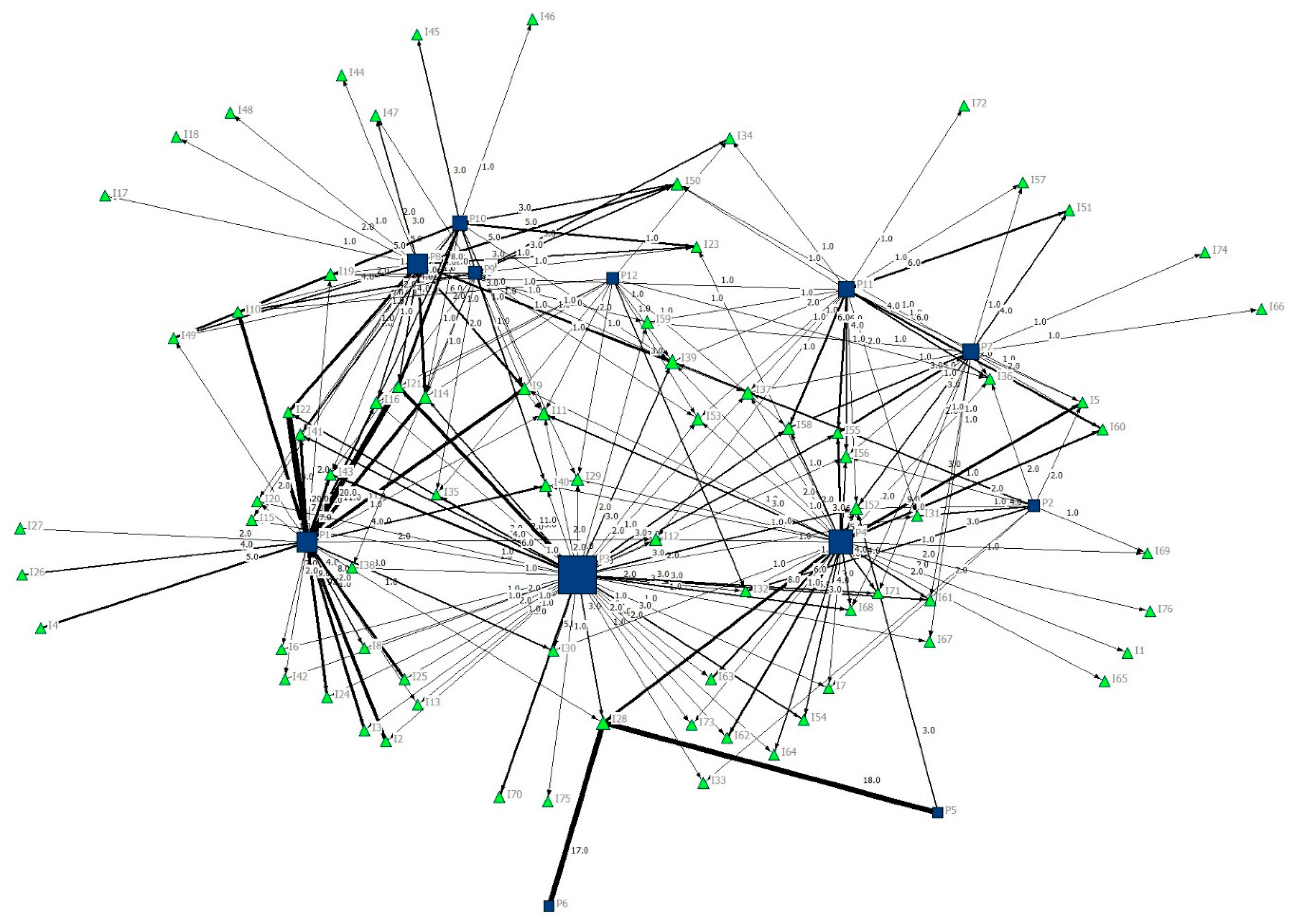

4.3. Issue Affiliation with Policy Institutions

4.4. Actor Interdependencies

4.5. Direct Payoff and Strategy Externalities of Policy Institutions

4.6. Indirect Payoff Externalities Between Policy Issues

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Label | Actor Full Name |

|---|---|

| H1 | Hong Kong Chief Executive |

| H2 | Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government |

| H3 | Hong Kong Chief Secretary for Administration |

| H4 | Hong Kong Financial Secretary |

| H5 | Hong Kong Environment Bureau |

| H6 | Hong Kong Environmental Protection Department |

| H7 | Hong Kong Air Science Group |

| H8 | Hong Kong Planning Department |

| H9 | Hong Kong Development Bureau |

| H10 | Hong Kong Agriculture Fisheries and Conservation Department |

| H11 | Hong Kong Innovation and Technology Bureau |

| H12 | Hong Kong Hone Affairs Bureau |

| H13 | Hong Kong Financial Services and the Treasury Bureau |

| H14 | Hong Kong Labor and Welfare Bureau |

| H15 | Hong Kong Transport and Housing Bureau |

| H16 | Hong Kong Transportation Department |

| H17 | Hong Kong Food and Health Bureau |

| H18 | Hong Kong Commerce and Economic Development Bureau |

| H19 | Hong Kong Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Bureau |

| H20 | Hong Kong Lands Department |

| H21 | Hong Kong Water Supplies Department |

| H22 | Hong Kong Food and Environmental Hygiene Department |

| H23 | Hong Kong Education Bureau |

| H24 | Hong Kong Security Bureau |

| G1 | Guangdong Party Secretary |

| G2 | Guangdong Governor |

| G3 | Guangdong Vice Governor |

| G4 | Guangdong Provincial Government |

| G5 | Guangdong Department of Ecology and Environment |

| G6 | Guangdong Department of Housing and Urban-Rural Construction |

| G7 | Guangdong Development and Reform Commission |

| G8 | Guangdong Department of Commerce |

| G9 | Guangdong Department of Civil Affairs |

| G10 | Guangdong Department of Science and Technology |

| G11 | Guangdong Department of Transportation |

| G12 | Guangdong Department of Water Conservancy |

| G13 | Guangdong Department of Forestry |

| G14 | Guangdong Department of Marine and Fisheries |

| G15 | Guangdong Department of Culture and Tourism |

| G16 | Guangdong Department of Public Security |

| G17 | Guangdong Department of Education |

| G18 | Guangdong Health Commission |

| G19 | Guangdong Drug Administration |

| G20 | Guangdong Meteorological Bureau |

| G21 | Guangdong Sports Bureau |

| G22 | Guangdong Information Office |

| G23 | Guangdong Traditional Chinese Medicine Bureau |

| G24 | Guangdong Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office |

| G25 | Standing Committee of Guangdong Provincial People’s Congress |

| A1 | Guangzhou Mayor |

| A2 | Guangzhou Municipal Government |

| A3 | Guangzhou Customs District |

| A4 | Shenzhen Mayor |

| A5 | Shenzhen Municipal Government |

| A6 | Shenzhen Bureau of Ecology and Environment |

| A7 | Zhuhai Mayor |

| A8 | Gongbei Customs |

| A9 | Foshan Municipal Government |

| A10 | Dongguan Municipal Government |

| A11 | Zhongshan Municipal Government |

| A12 | Zhuhai Municipal Government |

| A13 | Jiangmen Municipal Government |

| A14 | Zhaoqing Municipal Government |

| A15 | Huizhou Municipal Government |

| A16 | Qingyuan Municipal Government |

| A17 | Yunfu Municipal Government |

| A18 | Yangjiang Municipal Government |

| A19 | Shanwei Municipal Government |

| A20 | Heyuan Municipal Government |

| M1 | Macao Chief Executive |

| M2 | Macao Special Administrative Region Government |

| M3 | Macao Chief Executive Office |

| M4 | Macao Economic and Financial Secretary |

| M5 | Macao Economic Bureau |

| M6 | Macao Fire Bureau |

| M7 | Macao News Bureau |

| M8 | Macao Culture Bureau |

| M9 | Macao Health Bureau |

| M10 | Macao Sports Bureau |

| M11 | Macao Education and Youth Affairs Bureau |

| M12 | Macao Trade and Investment Promotion Institute |

| M13 | Macao Tourist Office |

| M14 | Macao Land, Public Work and Transport Bureau |

| M15 | Macao Science and Technology Commission |

| M16 | Macao Customs |

| M17 | Macao Security Department |

| M18 | Macao Environmental Protection Bureau |

| M19 | Macao Maritime and Water Bureau |

| M20 | Macao Geophysical and Meteorological Bureau |

| M21 | Macao Energy Development Office |

| M22 | Macao Transport Bureau |

| M23 | Macao Construction and Development Office |

| B1 | Fujian Governor |

| B2 | Jiangxi Governor |

| B3 | Hunan Governor |

| B4 | Guangxi Governor |

| B5 | Hainan Governor |

| B6 | Sichuan Governor |

| B7 | Guizhou Governor |

| B8 | Yunnan Governor |

| B9 | Yunnan Vice Governor |

| B10 | Fujian Provincial Government |

| B11 | Jiangxi Provincial Government |

| B12 | Hunan Provincial Government |

| B13 | Guangxi Provincial Government |

| B14 | Hainan Provincial Government |

| B15 | Sichuan Provincial Government |

| B16 | Guizhou Provincial Government |

| B17 | Yunnan Provincial Government |

| B18 | Fujian Department of Ecology and Environment |

| B19 | Jiangxi Department of Ecology and Environment |

| B20 | Hunan Department of Ecology and Environment |

| B21 | Guangxi Department of Ecology and Environment |

| B22 | Hainan Department of Ecology and Environment |

| B23 | Sichuan Department of Ecology and Environment |

| B24 | Guizhou Department of Ecology and Environment |

| B25 | Yunnan Department of Ecology and Environment |

| S1 | President |

| S2 | Premier |

| S3 | State Council |

| S4 | State Council Development Research Center |

| S5 | Ministry of Commerce |

| S6 | National Development and Reform Commission |

| S7 | Ministry of Transport |

| S8 | Ministry of Culture and Tourism |

| S9 | Ministry of Industry and Information Technology |

| S10 | General Administration of Customs |

| S11 | State Council Hong Kong and Macao Office |

| S12 | State Council Liaison Office in Hong Kong |

| S13 | South China Sea Branch State Ocean Administration |

| S14 | Ministry of Ecology and Environment |

| S15 | Ministry of Science and Technology |

Appendix B

| Label | Policy Issue |

|---|---|

| I1 | Cuiheng New Area |

| I2 | Shenzhen Bay |

| I3 | Mirs Bay |

| I4 | Fast River |

| I5 | Hengqin Island |

| I6 | Pearl River Estuary |

| I7 | Nansha New Area |

| I8 | Information disclosure |

| I9 | Information sharing |

| I10 | Technology exchange |

| I11 | Organizational coordination |

| I12 | Setting common goal |

| I13 | Formulating common plan |

| I14 | Joint monitoring |

| I15 | Joint enforcement |

| I16 | Monitoring network |

| I17 | Division of responsibilities |

| I18 | Pollution dispute settlement |

| I19 | Environmental emergency |

| I20 | Pollution warning |

| I21 | Air |

| I22 | Water |

| I23 | Solid waste |

| I24 | Marine resources nursing |

| I25 | Forest wetland protection |

| I26 | Wildlife conservation |

| I27 | Marine fish protection |

| I28 | CEPA |

| I29 | Quality life circle |

| I30 | Urban planning |

| I31 | Urban system planning |

| I32 | Urban agglomeration |

| I33 | Urban-rural integration |

| I34 | Low-carbon city |

| I35 | Circular economy |

| I36 | Industrial layout |

| I37 | Industrial upgrading |

| I38 | Collaboration industry-University-Research Institute |

| I39 | Environmental protection |

| I40 | Motor vehicle management |

| I41 | Total amount control |

| I42 | Emission trading |

| I43 | Clean production |

| I44 | Ecological compensation |

| I45 | Environmental impact assessment |

| I46 | Environmentally friendly procurement |

| I47 | Environmental protection research |

| I48 | Public participation |

| I49 | Environmental education |

| I50 | Environmental industry |

| I51 | Regional cooperation |

| I52 | Economy and trade |

| I53 | Finance |

| I54 | Port |

| I55 | Tourism |

| I56 | Infrastructure |

| I57 | Energy |

| I58 | Transportation |

| I59 | Information technology |

| I60 | Social livelihood |

| I61 | Education |

| I62 | Medical care |

| I63 | Medicine |

| I64 | Culture |

| I65 | Fire control |

| I66 | Media |

| I67 | Agriculture |

| I68 | Modern service |

| I69 | Fundamental public service |

| I70 | Property right |

| I71 | Food security |

| I72 | Irrigation works |

| I73 | Maritime search and rescue |

| I74 | Credit system |

| I75 | Weather forecast |

| I76 | Youth innovation and entrepreneurship |

References

- Hartley, K. Environmental resilience and intergovernmental collaboration in the Pearl River Delta. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2017, 34, 525–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Chan, C.K.; Dong, G.H.; Yim, S.H.L. Impacts of transboundary air pollution and local emissions on PM2.5 pollution in the Pearl River Delta region of China and the public health, and the policy implications. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 034005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Peng, S.; Liao, Y.; Long, W. The causes and impacts of water resources crises in the Pearl River Delta. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 177, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.F. Tackling cross-border environmental problems in Hong Kong: Initial responses and institutional constraints. China Q. 2002, 172, 986–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, A.; Xu, J. China’s Pan Pearl River Delta: Regional Cooperation and Development; Hong Kong University Press: Hong Kong, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Yeh, A. Governance and Planning of Mega-City Regions: An International Comparative Perspective; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J. Governing city regions in China: Theoretical discourses and perspectives for regional strategic planning. Town Plan. Rev. 2008, 79, 157–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C. Multilevel governance in the cross-boundary region of Hong Kong-Pearl River Delta, China. Environ. Plan. A 2005, 37, 2147–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C. The geopolitics of cross-boundary governance in the Greater Pearl River Delta, China: A case study of the proposed Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao Bridge. Political Geogr. 2006, 25, 817–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.M.; Bodin, O. Participation in multiple decision-making water governance forums in brazil enhances actors’ perceived level of influence. Policy Stud. J. 2018, 47, 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, T.A.; Greer, R.A. Polycentricity and the hollow state: Exploring shared personnel as a source of connectivity in fragmented urban systems. Policy Stud. J. 2018, 47, 52–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M.; Maag, S. What are cross-sectoral forums important to actors? Forum contributions to cooperation, learning and resource distribution. Policy Stud. J. 2019, 47, 114–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, N.E. The local community as an ecology of games. Am. J. Sociol. 1958, 64, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardo, R.; Lubell, M. The ecology of games as a theory of polycentricity: Recent advances and future challenges. Policy Stud. J. 2019, 47, 6–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubell, M. Governing institutional complexity: The ecology of games framework. Policy Stud. J. 2013, 41, 537–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubell, M.; Henry, A.D.; McCoy, M. Collaborative institutions in an ecology of games. Am. J. Political Sci. 2010, 54, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contractor, N.S.; Wasserman, S.; Faust, K. Testing multitheoretical, multilevel hypotheses about organizational networks: An analytic framework and empirical example. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 681–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharpf, F.W. Games Real Actors Play: Actor-Centred Institutionalism in Policy Research; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Purdy, J.M. A framework for assessing power in collaborative governance processes. Public Adm. Rev. 2012, 72, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braybrooke, D.; Lindblom, C.E. A Strategy of Decision: Policy Evaluation as a Social Process; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Saabatier, P.A.; Jenkins-Smith, H.C. Policy Change and Learning: An Advocacy Coalition Approach; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, S.; White, P.E. Exchange as a conceptual framework for the study of interorganizational relationships. Adm. Sci. Q. 1961, 5, 583–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kickert, W.J.M.; Klijn, E.H.; Koppenjan, J.F.M. Managing Complex Networks: Strategies for the Public Sector; Sage: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole, L.J. Strategies for intergovernmental management: Implementing programs in interorganizational networks. J. Public Adm. 1988, 11, 417–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teisman, G.R.; Klijn, E.H. Partnership arrangements: Governmental rhetoric or governance scheme? Public Adm. Rev. 2002, 62, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppenjan, J.; Klijn, E.H. Managing Uncertainties in Networks; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Klijn, E.H.; Koppenjan, J. Governance Networks in the Public Sector; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bednar, J.; Page, S. Can games theory explain culture? The emergence of cultural behavior within multiple games. Ration. Soc. 2007, 19, 65–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mewhirter, J.; Berardo, R. The impact of forum interdependence and network structure on actor performance in complex governance systems. Policy Stud. J. 2019, 47, 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative platforms as a governance strategy. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2018, 28, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spekkink, W.A.H.; Boons, F.A.A. The emergence of collaborations. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2016, 26, 613–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boons, F.A.A.; Berends, M. Stretching the boundary: The possibilities of flexibility as an organizational capability in industrial ecology. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2001, 10, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Jin, R.; Ning, X.; Skitmore, M.; Zhang, T. Prioritizing the sustainability objectives of major public projects in the Guangdong-Kong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, E.C.M.; Li, X.; Chen, T.; Lang, W. Deciphering the spatial structure of China’s megacity region: A new bay area—The Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area in the making. Cities 2018, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F. Developing a competitive Pearl River Delta in south China under one country-two systems. China J. 2007, 57, 160–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, A.G.; Sit, V.F.; Chen, G.; Zhou, Y. Developing a Competitive Pearl River Delta in South China Under One Country-Two Systems; Hong Kong University Press: Hong Kong, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hanneman, R.A.; Riddle, M. Introduction to Social Network Analysis; University of California: Riverside, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, R.; Spekkink, W. A running start or a clean slate? How a history of cooperation affects the ability of cities to cooperate on environmental governance. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, R. Role of law, position of actor and linkage of policy in China’s national environmental governance system, 1972–2016. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, M.S.; van de Ven, A.H.; Dooley, K.; Holmes, M.E. Organizational Change and Innovation Processes: Theory and Methods for Research; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative governance in theory and practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daley, D.M. Interdisciplinary problems and agency boundaries: Exploring effective cross-agency collaboration. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2009, 19, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, J.M.; Crosby, B.C.; Stone, M.M. The design and implementation of cross-sector collaborations: Propositions from the literature. Public Adm. Rev. 2006, 66 (Suppl. 1), 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, R.; de Jong, M.; Koppenjan, J. Assessing and explaining interagency collaboration performance: A comparative case study of local governments in China. Public Manag. Rev. 2019, 21, 581–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | City | Area (km2) | GDP (Billion USD) | Population (Million) | Industrial SO2 Emission (Thousand Ton) | Industrial Wastewater Discharge (Million Ton) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Guangzhou | 7436 | 285 | 14 | 63.3 | 225.6 |

| 2 | Shenzhen | 2007 | 283 | 11.9 | 8.2 | 120.1 |

| 3 | Foshan | 3875 | 125 | 7.5 | 79.4 | 148.2 |

| 4 | Dongguan | 2512 | 99 | 8.3 | 112.1 | 234.6 |

| 5 | Zhongshan | 1770 | 46 | 3.2 | 224.9 | 89.1 |

| 6 | Zhuhai | 1696 | 32 | 1.7 | 226.5 | 55.4 |

| 7 | Jiangmen | 9554 | 35 | 4.5 | 578.6 | 117.5 |

| 8 | Zhaoqing | 15,006 | 30 | 4.1 | 296.5 | 101.5 |

| 9 | Huizhou | 11,159 | 50 | 4.8 | 300.3 | 83.2 |

| 10 | Hong Kong | 1104 | 319 | 7.4 | 25.3 | n.a. |

| 11 | Macao | 29 | 45 | 0.6 | n.a. | 58.6 |

| Research Questions | Analytical Approaches | Measurement Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| (1) Which actors participate in which policy institutions? | Two-mode network: policy institution–actor network | Directed edge; weight of an edge; two-mode betweenness centrality. |

| (2) Which policy institutions deal with what issues? | Two-mode network: policy institution–issue network | Directed edge; weight of an edge; two-mode betweenness centrality. |

| (3) What is the pattern of actor interactions, and how are they interdependent? | One-mode network: actor network | Undirected edge; betweenness centrality. |

| (4) What are the direct payoff and strategy externalities between policy institutions? | One-mode network: policy institution network | Directed edge; betweenness centrality. |

| (5) What are the indirect payoff externalities between policy issues? | One-mode network: issue network | Undirected edge; betweenness centrality. |

| Policy Institution | Label | Initial Occurrence Time | Summary Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Guangdong–Hong Kong Liaison Group on Sustainable Development and Environmental Protection | P1 | 05/01/1983 | In response to the invitation of Hong Kong Environmental Protection (EP) Department, Guangdong’s and Hong Kong’s EP departments formally established regular communication mechanisms for mutual visits, exchanges, and notifications of EP status, especially in monitoring air and water quality. Seven years later, more governmental departments from the two places joined and built up a liaison group on EP to share and exchange EP experience and technologies. This liaison group mainly dealt with EP in the Mirs Bay Area. After ten years, the liaison group was upgraded into the Guangdong–Hong Kong liaison group on sustainable development and EP, and the EP issues have been expanded from air and water in the Mirs Bay Area to a broader range of EP issues in the whole geographical area. |

| Urban Planning of the Pearl River Delta | P2 | 26/06/1989 | Nine major cities (Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Foshan, Dongguan, Zhongshan, Zhuhai, Jiangmen, Zhaoqing, and Huizhou) in Guangdong Province, i.e., the Pearl River Delta (PRD), started to think about integrated urban planning at the regional scale. This policy institution emphasizes inter-local coordination on major infrastructure layouts and promotes integrated economic development. |

| Joint Meeting System of Guangdong–Hong Kong Cooperation | P3 | 30/03/1998 | This policy institution was established with the involvement of the top leaders in the two places to expand cooperation on EP between Guangdong and Hong Kong to other policy fields, including cooperation on port, infrastructure construction, urban planning, economy and trade, and public services. |

| Joint Meeting System of Guangdong–Macao Cooperation | P4 | 25/05/2001 | The policy institution of high-level meeting between Guangdong’s and Macao’s major leaders has become the main mechanism of coordinating important affairs between Guangdong and Macao. There are several special groups addressing cooperation on economic, trade, tourism, infrastructure, transportation, and EP. A liaison group on cooperation between Guangdong and Macao has also been established as a permanent body, holding at least one plenary meeting annually in Guangdong and Macao in turn. |

| Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement (CEPA) between the Mainland and Hong Kong | P5 | 19/12/2001 | The Ministry of Commerce of Mainland China and Hong Kong Financial Secretary built up this policy institution to promote closer economic and trade cooperation with special arrangements of removing administrative barriers. |

| Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement (CEPA) between the Mainland China and Macao | P6 | 20/06/2003 | The Ministry of Commerce of Mainland China and Macao Economic and Financial Secretary built up this policy institution to promote closer economic and trade cooperation with special arrangements of removing administrative barriers. |

| Pan Pearl River Delta Forum on Regional Cooperation and Development | P7 | 01/06/2004 | This policy institution was established to promote economic cooperation, not only within the PRD, but also between the PRD and its surrounding provinces including Fujian, Hunan, Guangxi, Hainan, Sichuan, Guizhou, and Yunnan, as well as the two special administrative regions, Hong Kong and Macao. |

| Pan Pearl River Delta Joint Meeting System of Cooperation on Environmental Protection | P8 | 16/07/2004 | This policy institution was established to promote cooperation on EP, not only within the PRD, but also between the PRD and its surrounding provinces including Fujian, Hunan, Guangxi, Hainan, Sichuan, Guizhou, and Yunnan, as well as the two special administrative regions, Hong Kong and Macao. |

| Macao International Environmental Cooperation Forum | P9 | 23/04/2008 | This policy institution was established to promote transfer of experience with EP, and exhibition and exchange of EP technologies. |

| Hong Kong-Macao Forum on Environmental Protection | P10 | 06/07/2008 | This policy institution was established to promote cooperation on EP between Hong Kong and Macao, and to facilitate exchange of experience and technology on EP. |

| Pan Pearl River Delta Joint Meeting System of Major Leaders | P11 | 25/07/2005 | This policy institution was set up to promote communication and coordination on regional cooperation in Pan PRD at a high authoritative level between governors of provinces (Fujian, Hunan, Guangxi, Hainan, Sichuan, Guizhou, and Yunnan) in the mainland and the two chief administrators of Hong Kong and Macao. |

| State-led Greater Bay Area Plan | P12 | 03/09/2014 | This policy institution was set up to facilitate the formulation of the Guangdong–Hong Kong-Macao GBA Plan. This GBA plan has been regarded as a national strategic plan to develop a globally competitive urban agglomeration. |

| Actors that are active in ≥4 policy institutions | Actors | Number of participating policy institutions |

| Guangdong Department of Ecology and Environment (G5) | 7 | |

| Guangdong Governor (G2) | 6 | |

| Macao Environmental Protection Bureau (M18) | 5 | |

| Guangdong Development and Reform Commission (G7) | 4 | |

| Hong Kong Chief Executive (H1) | 4 | |

| Hong Kong Environmental Protection Department (H6) | 4 | |

| President (S1) | 4 | |

| National Development and Reform Commission (S6) | 4 | |

| Top 10 actors that participate in policy games most | Actors | Number of participating games |

| Guangdong Department of Ecology and Environment (G5) | 87 | |

| Hong Kong Environmental Protection Department (H6) | 60 | |

| Guangdong Department of Housing and Urban-Rural Construction (G6) | 55 | |

| Guangdong Development and Reform Commission (G7) | 55 | |

| Macao Environmental Protection Bureau (M18) | 52 | |

| Guangdong Governor (G2) | 49 | |

| Guangdong Department of Marine and Fisheries (G14) | 46 | |

| Hong Kong Transportation Department (H16) | 38 | |

| Hong Kong Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Bureau (H19) | 38 | |

| Guangdong Vice Governor (G3) | 36 |

| Policy Institution | Number of Total Participating Actors | Number of Actors with the Same Frequency | Frequency of Participation |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 19 | 2 | 34 |

| 5 | 26 | ||

| 10 | 18 | ||

| 2 | 8 | ||

| P2 | 20 | 10 | 10 |

| 1 | 8 | ||

| 5 | 3 | ||

| 3 | 2 | ||

| 1 | 1 | ||

| P3 | 33 | 1 | 21 |

| 23 | 20 | ||

| 2 | 16 | ||

| 2 | 15 | ||

| 2 | 13 | ||

| 3 | 1 | ||

| P4 | 40 | 1 | 16 |

| 31 | 15 | ||

| 1 | 12 | ||

| 5 | 10 | ||

| 1 | 3 | ||

| 1 | 1 | ||

| P5 | 8 | 2 | 19 |

| 1 | 2 | ||

| 5 | 1 | ||

| P6 | 3 | 2 | 17 |

| 1 | 1 | ||

| P7 | 18 | 11 | 13 |

| 7 | 1 | ||

| P8 | 18 | 11 | 14 |

| 1 | 13 | ||

| 6 | 1 | ||

| P9 | 20 | 16 | 11 |

| 1 | 10 | ||

| 1 | 5 | ||

| 1 | 2 | ||

| 1 | 1 | ||

| P10 | 6 | 2 | 11 |

| 2 | 10 | ||

| 2 | 1 | ||

| P11 | 11 | 11 | 13 |

| P12 | 10 | 1 | 4 |

| 1 | 3 | ||

| 4 | 2 | ||

| 4 | 1 |

| Top 10 most central actors in bridging policy institutions | Actors | Two-mode betweenness centrality |

| Guangdong Department of Ecology and Environment (G5) | 0.248 | |

| Guangdong Development and Reform Commission (G7) | 0.092 | |

| Guangdong Governor (G2) | 0.081 | |

| Macao Environmental Protection Bureau (M18) | 0.072 | |

| Hong Kong Transportation Department (H6) | 0.039 | |

| Guangdong Vice Governor (G3) | 0.038 | |

| State Council Hong Kong and Macao Office (S11) | 0.036 | |

| Guangdong Department of Housing and Urban-Rural Construction (G6) | 0.033 | |

| Guangdong Provincial Government (G4) | 0.031 | |

| Hong Kong Chief Executive (H1) | 0.029 | |

| Ranking of importance of policy institutions in linking actors | Policy institutions | Two-mode betweenness centrality |

| Joint Meeting System of Guangdong–Macao Cooperation (P4) | 0.380 | |

| Joint Meeting System of Guangdong–Hong Kong Cooperation (P3) | 0.301 | |

| Urban Planning Pearl River Delta (P2) | 0.210 | |

| Guangdong–Hong Kong Liaison Group on Sustainable Development and Environmental Protection (P1) | 0.177 | |

| Pan Pearl River Delta Joint Meeting System of Cooperation on Environmental Protection (P8) | 0.177 | |

| Macao International Environmental Cooperation Forum (P9) | 0.146 | |

| Pan Pearl River Delta Forum on Regional Cooperation and Development (P7) | 0.091 | |

| Pan Pearl River Delta Joint Meeting System of Major Leaders (P11) | 0.072 | |

| Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement between the Mainland and Hong Kong (P5) | 0.063 | |

| Hong Kong-Macao Forum on Environmental Protection (P10) | 0.044 | |

| State-led Greater Bay Area Plan (P12) | 0.032 | |

| Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement between the Mainland and Macao (P6) | 0.004 |

| Issues that are affiliated with ≥4 policy institutions | Issues | Number of affiliated policy institutions |

| Environmental Protection (I39) | 8 | |

| Setting Common Goal (I12), Joint Monitoring (I14), Industrial Upgrading (I37), and Economy and Trade (I52) | 6 | |

| Organizational Coordination (I11), Monitoring Network(I16), Air (I21), CEPA (I28), Quality Life Circle (I29), Industrial Layout (I36), Motor Vehicle Management (I40), Environmental Industrial (I50), Finance (I53), Infrastructure (I56), and Transportation (I58) | 5 | |

| Hengqin Island (I5), Technology Exchange (I10), Environmental Emergency (I19), Water (I22), Solid Waste (I23), Urban Agglomeration (I32), Total Amount Control (I41), Clean Production (I43), Environmental Education (I49), Tourism (I55), and Information Technology (I59) | 4 | |

| Top 10 issues that are addressed in policy games most | Issues | Number of games addressing the issue |

| CEPA (I28) | 47 | |

| Air (I21) | 44 | |

| Water (I22) | 31 | |

| Joint Monitoring (I14) | 25 | |

| Technology Exchange (I10) | 22 | |

| Tourism (I55) | 20 | |

| Information Sharing (I9) | 19 | |

| Environmental Protection (I39) | 18 | |

| Monitoring Network (I16) | 16 | |

| Total Amount Control (I41) | 16 |

| Policy Institution | Number of total Affiliated Issues | Number of Issues with the Same Frequency | Frequency of Issue Involvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 56 | 3 | 11 |

| 2 | 9 | ||

| 1 | 8 | ||

| 2 | 7 | ||

| 2 | 6 | ||

| 1 | 5 | ||

| 3 | 4 | ||

| 1 | 3 | ||

| 9 | 2 | ||

| 4 | 1 | ||

| P2 | 11 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | 3 | ||

| 1 | 2 | ||

| 2 | 1 | ||

| P3 | 47 | 1 | 11 |

| 1 | 6 | ||

| 1 | 5 | ||

| 1 | 4 | ||

| 10 | 3 | ||

| 15 | 2 | ||

| 18 | 1 | ||

| P4 | 32 | 1 | 9 |

| 1 | 8 | ||

| 3 | 6 | ||

| 2 | 5 | ||

| 4 | 4 | ||

| 4 | 3 | ||

| 8 | 2 | ||

| 9 | 1 | ||

| P5 | 2 | 1 | 18 |

| 1 | 3 | ||

| P6 | 1 | 1 | 17 |

| P7 | 18 | 1 | 5 |

| 1 | 4 | ||

| 2 | 3 | ||

| 3 | 2 | ||

| 11 | 1 | ||

| P8 | 22 | 2 | 7 |

| 1 | 6 | ||

| 2 | 5 | ||

| 2 | 4 | ||

| 3 | 3 | ||

| 4 | 2 | ||

| 8 | 1 | ||

| P9 | 15 | 1 | 4 |

| 2 | 3 | ||

| 2 | 2 | ||

| 10 | 1 | ||

| P10 | 15 | 1 | 8 |

| 3 | 5 | ||

| 2 | 4 | ||

| 3 | 3 | ||

| 2 | 2 | ||

| 4 | 1 | ||

| P11 | 19 | 4 | 6 |

| 2 | 4 | ||

| 2 | 2 | ||

| 11 | 1 | ||

| P12 | 13 | 1 | 3 |

| 1 | 2 | ||

| 11 | 1 |

| Top 10 most central issues in bridging policy institutions | Label of issues | Two-mode betweenness centrality |

| CEPA (I28) | 0.042 | |

| Environmental Protection (I39) | 0.042 | |

| Industrial Upgrading (I37) | 0.030 | |

| Economy and Trade (I52) | 0.027 | |

| Organizational Coordination (I11) | 0.026 | |

| Environmental Industry (I50) | 0.021 | |

| Joint Monitoring (I14) | 0.018 | |

| Motor Vehicle Management (I40) | 0.017 | |

| Information Technology (I59) | 0.017 | |

| Quality Life Circle (I29) | 0.015 | |

| Ranking of importance of policy institutions in linking issues | Label of policy institutions | Two-mode betweenness centrality |

| Joint Meeting System of Guangdong–Hong Kong Cooperation (P3) | 0.409 | |

| Joint Meeting System of Guangdong–Macao Cooperation (P4) | 0.206 | |

| Guangdong–Hong Kong Liaison Group on Sustainable Development and Environmental Protection (P1) | 0.152 | |

| Pan Pearl River Delta Joint Meeting System of Cooperation on Environmental Protection (P8) | 0.145 | |

| Pan Pearl River Delta Joint Meeting System of Major Leaders (P11) | 0.089 | |

| Pan Pearl River Delta Forum on Regional Cooperation and Development (P7) | 0.086 | |

| Hong Kong–Macao Forum on Environmental Protection (P10) | 0.063 | |

| Macao International Environmental Cooperation Forum (P9) | 0.039 | |

| State-led Greater Bay Area Plan (P12) | 0.026 | |

| Urban Planning of the Pearl River Delta (P2) | 0.017 | |

| Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement between the Mainland and Hong Kong (P5) | 0.000 | |

| Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement between the Mainland and Macao (P6) | 0.000 |

| Label | One-Mode betweenness Centrality | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | P8 | P9 | P10 | P11 | P12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G5 | 8.658 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| G7 | 4.022 | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| G2 | 2.921 | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| M18 | 2.800 | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| G6 | 2.434 | x | x | x | |||||||||

| S11 | 2.380 | x | x | x | |||||||||

| G4 | 1.628 | x | x | x | |||||||||

| G3 | 1.387 | x | x | x | |||||||||

| H6 | 1.331 | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| G24 | 1.329 | x | x |

| Policy Institution | One-Mode betweenness Centrality |

|---|---|

| P7 | 22.152 |

| P12 | 21.485 |

| P3 | 11.939 |

| P8 | 9.606 |

| P11 | 8.303 |

| P4 | 7.424 |

| P9 | 3.636 |

| P2 | 2.424 |

| P1 | 0.909 |

| P5 | 0.606 |

| P6 | 0.606 |

| P10 | 0.000 |

| Label | One-Mode betweenness Centrality | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | P8 | P9 | P10 | P11 | P12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I21 | 8.880 | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| I9 | 5.842 | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| I55 | 5.165 | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| I58 | 4.566 | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| I39 | 4.051 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| I43 | 3.957 | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| I14 | 3.641 | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| I22 | 3.339 | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| I71 | 2.873 | x | x | x | |||||||||

| I40 | 2.631 | x | x | x | x | x |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, W.; Mu, R. Exploring Coordinative Mechanisms for Environmental Governance in Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area: An Ecology of Games Framework. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3119. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113119

Zhou W, Mu R. Exploring Coordinative Mechanisms for Environmental Governance in Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area: An Ecology of Games Framework. Sustainability. 2019; 11(11):3119. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113119

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Wenjie, and Rui Mu. 2019. "Exploring Coordinative Mechanisms for Environmental Governance in Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area: An Ecology of Games Framework" Sustainability 11, no. 11: 3119. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113119

APA StyleZhou, W., & Mu, R. (2019). Exploring Coordinative Mechanisms for Environmental Governance in Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area: An Ecology of Games Framework. Sustainability, 11(11), 3119. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113119