1. Introduction

The wide range of understandings of governance has been already demonstrated (see e.g., [

1]) and its context alongside environment and sustainable development is widely recognized [

2,

3,

4,

5]. This section considers global environmental governance broadly as a continuous worldwide complex of procedures and results in a multi-level interplay among different institutions and actors including organizations in space and time concerning natural assets. Organizations and individual actors are understood in this context as “players of the game” while institutions such as law constitute the “rules of the game” [

6,

7]. In terms of organizations as actors, UN Environment (former United Nations Environmental Program—UNEP), the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) are particularly relevant in the biodiversity context [

8,

9,

10]. Similar is valid for the—under their aegis adopted and administered—Multilateral Environmental Agreements—MEAs [

11,

12,

13].

When it comes to biodiversity, these relevant institutions are in particular:

the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora—CITES opened for signature in 1973 [

14,

15],

the Convention on Biological Diversity—CBD [

16,

17,

18,

19] opened for signature 1992, and

the Convention on Migratory Species—CMS opened for signature [

9,

20,

21,

22],

all administered by (nowadays) UN Environment (on the particular relationship see—e.g., on the example of the CBD—in the COP 10 Decision X/45 (titled “X/45.Administration of the Convention and budget for the program of work for the biennium 2011-2012) the Annex I titled “Revised Administrative Arrangements between the United Nationa Environment Program (UNEP) and the Secretariat of the Convention on Biologiscal Deversits (CBD)” available at

https://www.cbd.int/decision/cop/?id=12311 (19 March 2019)).

Furthermore:

the Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage opened for signature 1972 and administered by UNESCO [

23], and

the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture adopted 2001 and administered by the FAO [

24,

25].

Further non-UN organizations and global environment related normative complexes such as:

the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) administering e.g., the Ramsar Convention on wetlands of international importance adopted in 1971 [

26,

27,

28,

29],

Other agreements without environmental focus and without UN-context such as the WTO-agreements (but often with much influence on the environment; see e.g., [

30,

31,

32,

33] are also worth mentioning in this context.

While the organizations overall administer these institutions which were concluded under their aegis, the concrete administrative units are usually laid down in the institutions and, thus, created by these institutions.

They are usually called “secretariats” and these MEA-secretariats are widely seen as significant players in this global environmental governance [

34,

35,

36]. Their scope of work is in particular determined by the conventions themselves.

The grade of detailedness of these documents and the extent to which they are formulated in a binding way circumscribe the frame of freedom and discretion for the work of these secretariats.

2. Overview and Hypotheses

Naturally, the goal, nature, structure and tasks of these administrative units also vary according to the (UN-)organizations under whose aegis they were launched as the organizations involved show different membership of Parties. But apparently also among MEAs concluded under the aegis of one and the same (UN-)organization, the characteristics of the secretariats vary considerably. This can be shown by a short look at the wording of three articles of three conventions, all launched under the aegis of the former United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP), now UN Environment (

Table 1, text in bold highlighted by the author).

Parts that particularly address functions are highlighted in bold in

Table 1. All the three Articles cited have not been amended since their indicated year of opening for signature. An initial look seems to indicate huge differences among these three “UNEP”-conventions. Overall in quantitative terms, the total length of their respective norms is by far the shortest with the youngest one (CBD).

This impression is a bit misleading in several ways:

Each of the articles lists in the final sub-paragraph the different function an – in each case quite differently formulated (unlike CITES and CMS, the CBD formulates the extension of the functions solely as a possibility by using “may be”; CITES simply refers to “Parties” but the newer CMS and CBD-texts clarify the COP as the unique decision-making organ of conventions. ART. I/h CITES defines “Party” which “means a State for which the present Convention has entered into force”)—extension of the functions (it is worth mentioning that this extension possibility within CITES and CMS covers “any” functions while the CBD seems to reflect “such functions” to the preceding norm) of the Secretariat, where the CITES norm provides the most potential and the CBD norm the least.

The article of the CITES refers to two of its other articles where further functions of the Secretariat are stipulated. Art. XII/2/b refers to Art. XV (Article XV CITES has the title “Amendments to Appendices I and II” and provides the procedure therefore; see

Appendix A, derived therefrom) and XVI (Art. XVI CITES has the title “Appendix III and Amendments thereto” and provides substantial and procedural norms (see

Appendix B).

The article of the CMS refers more generally to other functions trusted to the Secretariat under this Convention (Art. IX/4/k. The Secretariat is—outside of Art. IX CMS—mentioned in this convention another 22 times, reaching from purely passive behavior such as receiving information by the Parties (Art. III/7; IV/5, VI/1,VII/9, VIII/3, 20/3 and 20/4 CMS) or—assumed upon (discretional)—requesting scientific advice by the Scientific Council (VIII/5/a CMS) to very active functions such as keeping the list of range states up to date (Art. VI/1 CMS) and forwarding information in connection with convening meetings (Art. VII/2, VII/3, VIII/3 CMS) and with amendments to the Convention or its Appendices (Art. X/3 and XI/3 CMS).

The article of the CBD adds functions assigned by any—unique to the CBD out of the three conventions—Protocol (Art. 24/2/b) whereby currently two Protocols are in force (see the information about the Cartagena Protocol and the Nagoya Protocol provided at

https://www.cbd.int/ (accessed 19 March 2019); see also the Nagoya—Kuala Lumpur Supplementary Protocol on Liability and Redress to the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety (

https://bch.cbd.int/protocol/supplementary/, 19 March 2019). See Art. IX/4/b, g and h CMS and for an overview on the current seven AGREEMENTS (

http://www.cms.int/en/cms-instruments/agreements, accessed 19 March 2019).

The article of the CMS already explicitly relates functions to a unique instrument among the three compared conventions, namely its AGREEMENTS (see Art. IX/4/b, g and h CMS and for an overview on the current seven AGREEMENTS (

http://www.cms.int/en/cms-instruments/agreements, accessed 19 March 2019).

Each of these four normative complexes adds at least theoretical, but often practical and current functions to the work of the respective Secretariat which can again contain functions that provide discretion to the Secretariat.

The full assessment of this potential and factual extension through these four normative complexes cannot be covered by the intentional length of this article and therefore lies outside of its scope. For example, an assessment of the extension indicated under point 1 above would require at least an analysis of all the resolutions released by all the three Conferences of Parties (CITES simply refers to “Parties” but the newer CMS and CBD-texts clarify the COP as unique decision-making organ of conventions). Similarly, the assessment of the extension indicated under point 4 above would require additionally assessing the entire Protocols to the CBD.

Instead, the assessment in this paper concentrates on the above cited text of the conventions and its references to the text of the conventions itself.

An initial overall view indicates in this regard a quite broad range of norms in Art. XII CITES which are capable of providing discretion to the Secretariat under this convention. While Art. IX CMS (subject to a closer assessment of its wider reference to the other norms of this convention) and in particular Art. 24 CBD contain much fewer norms that are capable of providing discretion to their respective Secretariats.

Thus, the hypothesis to be assessed in the further detailed analysis are firstly, that the CBD as the youngest of the three “UNEP”-conventions selected a lesser extent of norms providing discretion to its respective Secretariat compared with CITES. Secondly, a similar hypothesis is analysed for the CMS as the second youngest convention assessed.

These hypotheses will be assessed in detail in the following through the research question in how far the norms defining Secretariats’ functions differ qualitatively and even semi-quantitatively. Furthermore the research assesses based on the literature in how far these functions laid down are also reflecting actual functions implemented by the respective Secretariat within these three MEAs. The analysis will start with a detailed qualitative comparison—by means of literal interpretation of eleven “normative clusters”—of the norms already highlighted in

Table 1. The order of the clusters assessed follows the chronological order of occurrence of these normative cluster topics within the text of the Conventions. Afterwards qualitative results are summarized in a semi-quantitative and comparative evaluation of the number of functions and the extent of discretion provided therein. These summarized results are further discussed from general, formal and informal points of views. Furthermore for differences among the three conventions, a search for and discussion of potential explanations is implemented also based on the literature. Conclusions about the main findings and main discussion points follow at the end of this paper.

3. Detailed Qualitative Comparison

The convention norms outlined in

Table 1 will now be comparatively and qualitative assessed in a descriptive way regarding their extent of discretion and the results are presented in eleven “normative clusters”.

3.1. Discretion Regarding Meeting Arrangements and Services

Within this first normative cluster, the norms in all three conventions read generally similar. The CITES norm uses “meetings of the Parties” which sounds as if also covering for bi- and trilateral meetings and therefore wider than the other two rules that refer to the “Conference of the Parties” (see Art. XII/2/a CITES in comparison to Art. IX/4/a/I CMS and Art. 24/1/a CBD). This is backed up by the finding that CITES uses the terms “meetings of the Parties” (Art. XII/2/a and Art. XII/2/f CITES), “Conference of the Parties” (Art. XII/2/c), “the Parties” (five times in Art. XII/2/e, f, g and i) as well as “Parties” (two times in Art. XII/2/d) in separate and parallel ways, even within one paragraph of one Article and unlike the other two conventions. The CBD only uses in Art. 24/1 the term “Conference of the Parties” (in total three times) and the CMS in Art. IX/4 too (in total 6 times), except in one case—naturally—related in connection with the promotion of liaison between “the Parties”(Art. IX/4/b CMS) and in one case regarding the function to make available a list of AGREEMENTS (Art. IX/4/h). Latter case shows that the CMS uses “Conference of the Parties” and “the Parties” even in one sub-paragraph together (Art. IX/4/h CMS), but intentionally due to different contexts in a distinguished way (only “the Conference of the Parties”—but not “the Parties”—can request the information—beyond the sole list—is provided by the Secretariat. This wider formulation of the CITES is, in comparison, somehow mitigated by the additional references in the CMS to meetings of the Scientific Council (see Art. IX/4/b CMS; and see also the already mentioned duties of the Secretariat to forward information in connection with convening meetings (Art. VII/2, VII/3, VIII/3 CMS backed up by Art. IX/4/b CMS) and in the CBD to the Protocols (the Secretariat receives in the CBD similar duties—like in the CMS-Secretariat for its scientific body—for its Subsidiary body on scientific, technical and technological advice (SBSTTA) in particular via Art. 25/3 CBD for further information see e.g., [

37] who refer at page 508 to the modus operandi of the SBSTTA; [

38] (p. 268) also indicates that “…the secretariat has to serve….SBSTTA”), respectively. All three norms of all three conventions assessed predetermine significant discretion on behalf of the respective secretariat by using in particular the verb “to service”. Thus, at the first stage it is up to the respective secretariat to estimate and decide whether a specific activity (or inactivity) fulfils this criterion.

3.2. Discretion Regarding the Procedures for Amendments

The procedures for amendments in Art. XV and XVI CITES are rather prescribing straight-forward duties of the Secretariat. The largest opportunity of the Secretariat to execute discretion seems to lay in the interpretation of the term “immediately” with regard to the communication of amendment proposals that it received from the Parties (Art. XV/2/b and c CITES). This extent of discretion is rather negligible. As already mentioned, the CMS also contains duties of the Secretariat to forward information in connection with amendments to the Convention or its Appendices (Art. IX/4/k in conjunction with Art. X/3 and XI/3 CMS). Also here, no significant extent of discretion is visible.

3.3. Discretion Regarding Undertaking Scientific and Technical Studies

3.3.1. CITES Secretariat

The CITES Secretariat has the explicit function to undertake scientific and technical studies (Art. XII/2/c). This Secretariat’s discretion in doing so is limited in several ways. A first precondition is that this function has to comply with at least one program authorized by the COP. Apparently the program need not be explicitly released by the COP for this function. Furthermore, the program does not need to require or request a certain action under this specific function. Thus, the CITES Secretariat has first to check whether there is an official and related program of the COP out there. A draft would be insufficient. Without any program, studies cannot be undertaken. Furthermore, the Secretariat has to ensure that its studies are in accordance with this program. That would be for example the case if a study itself constitutes an implementation measure of that program or supports other such implementation measures of that program. The accordance has to be ensured during the whole execution of the study. If the initial accordance with the program falls away at a later stage during the execution of the study, for example because the program is cancelled or finished, the study would lack a legal requirement to be continued. The CITES Secretariat definitely has in this whole context certain discretion to assume whether the study is implemented in accordance with the COP-program but the COP can execute its supervision function for controlling this discretion.

This whole decision making complex, according to the CITES is also subject to the clause “as will contribute to the implementation of the present Convention” (Art. XII/2/c CITES). One could ask whether this clause refers to the studies alone or the program alone. But from the logic of the structure of the convention it should be clear that both instruments are covered. The hierarchical order needs to be secured, namely that no study be undertaken that disaccords with programs authorized by the COP and that both instruments, the studies and the authorized programs, need to contribute as implementation tools to CITES. Thus, the discretion of the Secretariat regarding its studies undertaken is double-bounded: on one end by the accordance with the COP-program and on the other end by the requirement to implement CITES.

Which studies as such are undertaken, lays quite widely within the discretion of the Secretariat. The kind of studies can be either scientific or technical, or both. They are not limited to the ones explicitly mentioned in the Art. XII/2/c CITES, namely “studies concerning standards for appropriate preparation and shipment of living specimens and the means of identifying specimens”. This is made clear through the use of the word “including” in this norm. As these are solely examples, the Secretariat is also not obliged to undertake these exemplified studies if there is no clear—explicit or implicit—instruction or program by the COP indicating to do so. Moreover, the CITES Secretariat can by means of imaginative interpretation of the COP programs and the convention justify by inventive arguments a wide range of such studies. Not only existing scientific and technical themes can be covered but also studies with an exploratory direction to find new solutions.

At the first sight, the term “the function of the Secretariat shall be to c) undertake….studies” might literally indicate that the CITES-Secretariat has to implement these studies itself. Given the limited staff number and wide range of potential topics, this literal interpretation is not realistic. An understanding that the Secretariat has to be finally responsible for each study implemented under its auspices appears to be more appropriate.

3.3.2. CMS Secretariat

In comparison with CITES, the CMS and the CBD do not show such an explicit function related to reports.

Art. IX/4/c CMS comes near, and could be even understood more widely in comparison to CITES. It stipulates the function of the CMS-Secretariat “to obtain from any appropriate source reports and other information which will further the objectives and implementation of this Convention and to arrange for the appropriate dissemination of such information”.

Whether this function can be understood more widely in comparison to CITES, depends on the interpretation of the verb “to obtain”. If it has to be understood solely in the sense of “to receive”, it would primarily lay down a rather passive function of the CMS-Secretariat. No justified reasons are visible why the activities should be restricted to a solely passive position in this way. Thus, rather—and in addition to a passive function—an active understanding of “to obtain” in the sense of “to acquire” and even “to procure” should be given preference.

Such an interpretation grants to the CMS Secretariat the usage of the same channels of info-collection such as the CITES Secretariat.

With regard to the kind of information, the formulation of the CMS is even wider and gives to the CMS Secretariat a broad range of discretion. Unlike the CITES Secretariat, the CMS Secretariat is not—at least literallylimited to “studies”. But all kinds of information are covered whereby “reports” are simply exemplified. Similarly wide discretion is granted with regard to the source of the information (namely, “any appropriate source is allowed”; an issue which CITES does not approach at all). The source could even be a report executed by the CMS-Secretariat itself if it is adequately equipped to implement such a report. One restriction might be that the information obtained is “new” although it was produced inside and through the capacity of the CMS Secretariat.

This goes hand in hand with the overall condition that limits all the discretion of the CMS Secretariat with regard to obtaining information. The information has explicitly to further the objectives and implementation of the CMS. Information which is not new within the Secretariat does not fulfil this criterion as it is already there and, thus, ongoing and benign to the CMS.

This overall condition is determined in a final way and does not involve a second actor and/or any procedural step and/or a further instrument. The CMS Secretariat enjoys much further discretion in comparison to the CITES Secretariat which is—such as shown—bound to the precondition of “accordance with programs authorized by the COP”.

However, one of the explicit functions of the CMS Secretariat is to “arrange for the appropriate dissemination of such information”. Also therein, the word “appropriate” grants discretion. The Secretariat can execute this discretion with regard to the means and the time of dissemination. There might also be cases where it is appropriate not to provide the information to all Parties and other stakeholders. This could be the case if information is solely relevant for the Range States of a species.

3.3.3. CBD Secretariat

Art. 24 CBD does not contain any explicit expressions in terms of information gathering. The norm only stipulates as one function of the Secretariat to “(c) to prepare reports on the execution of its functions under this Convention and present them to the Conference of the Parties;” (Art. 24/1/c CBD). However, this duty communicates with similar reporting duties also laid down in the other two conventions (see below). The CBD also only mentions the Secretariat—besides in Art. 23 (cited in Art. 24/1/a)—in connection with the adoption of Protocols (Art. 28/3 CBD “3. The text of any proposed Protocol shall be communicated to the Contracting Parties by the Secretariat at least six months before such a meeting”), with the amendment of the Convention or Protocols (Art. 29/3 CBD), and with some interim arrangements from the initial time of the CBD (Art. 40 CBD) arbitration (ANNEX II in connection with Art. 27/3/a and 27/4 CBD). Thus, these and not others are the functions to be reported upon in addition to the ones stipulated in Art. 24 CBD.

3.3.4. Additional Aspects Regarding the Relationship among Secretariats and Scientific Bodies

The explicit and broadly formulated function of the CITES secretariat described above to undertake scientific and technical studies should also be seen in another context. Unlike the CMS and the CBD, no scientific body has been included within the conventions’ original text itself. CITES’ scientific Animal and Plant Committees were not established earlier than 14 years after the conventions’ opening for signature (see also

https://www.cites.org/eng/disc/ac_pc.php, accessed 19 March 2019). The sixth meeting of the Conference of the Parties in Ottawa in 1987 laid down in an own resolution the details for these expert groups and their tasks to provide technical support to decision-making about certain species that are (or might become) subject to CITES trade controls (Resolution Conf. 11.1 (Rev. CoP17) with details in

Appendix B of this Resolution). Thus, the CITES Secretariat was already obliged to play an active scientific function for more than one decade prior to the establishment of expert groups within the convention. Even after the establishment of these groups, this explicitly laid out task of the Secretariat was not withdrawn from CITES.

While the CMS and CBD Secretariats were both from the very beginning of their establishment confident in their entrustment of additional scientific bodies and the further organizational and functional development of these bodies to deliver scientific expertise in the frame of their respective conventions.

3.4. Discretion Regarding Inviting Attention of the Parties/COPs

The Secretariats of CITES and CMS share similar discretion regarding inviting attention to any matter pertaining to the aims (CITES)/objectives (CMS) of their respective conventions. A significant difference contains the formulation of the addresses of such invitations. While CITES refers to “the Parties”, the CMS stipulates “the Conference of the Parties”.

Again, if this is understood in a way that also single Parties or a group of Parties are to be covered besides all Parties together, even outside of the COPs, this equips the CITES Secretariat with much more flexibility and affords a much higher degree of discretion in comparison to the CMS Secretariat.

Neither Art. 24 CBD, nor any other Article of the CBD contains such an explicit permit. Nevertheless, the arrangement of the COPs as an explicit task of the CBD-Secretariat may enshrine opportunities to raise similar attention among the Parties, but limited to this connection with the COPs.

3.5. Discretion Regarding Publications

3.5.1. CITES

Art. XII/2/f CITES formulates this function of the Secretariat “to publish periodically and distribute to the Parties current editions of Appendices I, II and III together with any information which will facilitate identification of specimens of species included in those Appendices”. Discretion is therefore provided regarding the means of publishing where the discretion will be restricted—if at all—by terms such as “adequate” and/or “appropriate” publication tool. A similar extent of discretion is also granted concerning the time interval. Because any occasion regularly coming back can be— theoretically—considered “periodically”. Even the understanding what a period is can change over time and does not realistically have to stay the same. The term “current” in this clause cited can be seen corresponding to “periodically” (and therefore provide discretion) or as something independent from it (and therefore providing no discretion).

The former understanding is supported by the fact that modifications of the Appendices enter into effect after a certain duration following their conclusion at the COPs (Art. XV/1/c CITES speaks about “….entering into force 90 days after….”; Art. XVI/3 CITES refers to “….shall take effect 30 days after ….”, whereas “entering into force” and “shall take effect” can be synonymously understood here). Thus, a publication is no precondition and current information can be still considered “current” if it is published some while after the start of its legal relevance (notwithstanding the impression that this mode is also somehow critical in terms of (a potential lack of) publicity to let affected third parties know about modifications of norms that might directly affect their business).

The latter understanding is supported by the argument that, actually, a list that is not up to date cannot be considered “current”. Additionally, the Appendices might not change periodically but occasionally and therefore irregularly.

A middle way of interpretation is that the Secretariat has discretion to publish a modification of Appendices and related information after the conclusion of the modification but before these modifications enter into force and, ideally as early as technically possible within this period in order to allow anyone potentially affected by the changes to adapt early.

Some further discretion could be argued in this clause cited as it refers to “the Parties” and not to “the Conference of the Parties”. Thus, the Secretariat can decide to address the Parties also individually or without context to the Conference of the Parties. But it seems to be obvious that no discretion exists whether all Parties or only a few of them should be included in the distribution. The editions of the Appendices as well as the related information are—as a matter of global trade— relevant to all Parties, even if the species does not yet occur in the wild in the country or is not yet traded in the country (an analogous understanding could be found in transnational environmental law e.g., in early judgements on the EU-Birds Directive (from 8. July 1987,

Commission v Belgium, 247/85 (1987) ECR 3029, para. 22; from 27. April 1988,

Commission v France, 252/85 (1988) ECR 2243, para. 5; from 8. February 1996,

Vergy, C-149/94, (1996) ECR I-299, paras. 17 und 18 and from 12. July 2007, C-507/04,

Commission v Austria (2007) ECR I-5939, para. 99), to be found in

http://curia.europa.eu/juris/recherche.jsf?language=en; 19 March 2019).

3.5.2. CMS and CBD

Art. IX CMS and Art. 24 CBD do not literally refer to publications, but the CMS contains a very general and broad reference to the “general public” (Art. IX/4/j CMS) which should be provided information concerning this Convention and its objectives by the Secretariat. Written publications are not necessarily the (only) means, although often useful or at least appropriate. The Secretariat also has the discretion to select any other means to do so, such as audio-services.

However, explicit functions of the CMS-Secretariat to publish are laid down in the CMS in Art. IX/4/f (regarding the list of Range States) and Art. IX/4/i (regarding certain recommendations and decisions of the COP). The earlier provision could include some discretion of the Secretariat as the definitions of the CMS about “range state” contains some legal terms which can be subject to interpretation (see e.g., “normal migration route” in Art. 1/f CMS in combination with Art. 1/h CMS). The latter provision does provide discretion to the Secretariat only insofar as there is no clear time indication laid down regarding when and how often such a publication should take place.

3.6. Discretion Regarding Active Reporting

The functions of the Secretariats in connection with the gathering of scientific reports and related information has already been assessed above related to discretion. What remains, is to analyze the Secretariat’s reporting on its own work to the Parties/COPs.

3.6.1. CITES

CITES obliges the Secretariat to prepare annual reports to “the Parties” (Art. XII/2/g, see above also the discussion of the addressees of the Secretariat’s work in CITES) while COPs take place “…at least once every two years…” (see Art. XI/1 CITES “

…, unless the Conference decides otherwise, and extraordinary meetings at any time on the written request of at least one-third of the Parties.” In fact, meetings of the COPs took place about every three years; for a list of dates and venues see

https://www.cites.org/eng/disc/cop.php; accessed 19 March 2019). There is no explicit reference to the COP in terms of time when to prepare and how to let “the Parties” know about the annual report. This would in theory provide discretion to the Secretariat. However, a time cycle related to the COP definitely makes sense in particular as the reports can be discussed there all together in the plenum. Similar is valid for the annual reports on the implementation of this convention also foreseen by this Article. In any way, some discretion for the Secretariat remains in both cases about what content it includes regarding “its own work” and “implementation” in terms of structure, topics and degree of detailedness.

Finally, only the CITES-Secretariat explicitly has the duty to prepare other reports as meetings of the Parties may request (see last part of Art. XII/2/g). If subject and timeline of these (no limited to annual) reports are clearly determined by the Parties in their meeting (not just the COPs), then only some discretion remains on the contents—but subject to supervision by the requesting meeting of the Parties.

3.6.2. CMS

The reports to be prepared by the CMS-Secretariat also contain regarding general content both the work of the Secretariat as well as work on the implementation of CMS (Art. IX/4/e CMS). All work of the Secretariat (should be and) is regularly also related to the conventions’ implementation in the widest sense. Thus, the term “on the implementation of the Convention” is to be understood as other implementation issues not related to the work of the Secretariat (e.g., work of third Parties which the Secretariat became—not within its active or passive functions but—unexpectedly aware of).

3.6.3. CBD

Art. 24/1/c CBD formulates the functions of its Secretariat regarding active reporting twofold slightly differently in comparison to CITES and CMs. Firstly, it does not generally refer to any implementation of the convention but to the “execution” of the Secretariats’ functions under this convention. This seems—at least literally—here to exclude implementing contributions of third parties outside of the active and passive functions of the Secretariat (and the discretion of the Secretariat to select such contributions for the report). Secondly, the Article adds to the preparation function also—unlike CITES and CMS—a presentation function. Both are—only—owed to the Conference of the Parties. When preparing the presentation, the Secretariat also has again some discretion with regard to the selection of the different elements of the content including style and structure, but subject to the supervision executed by the COP. Thus, for example if questions regarding this report’s presentation pop up during a committee meeting or in the plenary session, the General Secretary of the Secretariat might—be called in if not present and—need to provide explanations and/or justifications.

3.7. Discretion Regarding “Passive” Reporting

Only CITES stipulates explicit “passive” functions with regard to reporting, but in combination with further “active functions” (Art. XII/2/d CITES) which provide additional discretion to the Secretariat. The—passive—function there “to study the reports of Parties” follows the—active—function “to request from Parties such further information with respect thereto as it deems necessary to ensure implementation of the present Convention”. Both, and in particular the second function explicitly allow the Secretariat to interact with the Parties whenever it considers it to be required. Furthermore these functions are related to any or all Parties.

3.8. Discretion Regarding Making Recommendations

Only CITES also lays down explicitly the Secretariat’s function to make recommendations in a quite far-reaching sense (see Art. XII/2/h CITES). They can concern not only the aims of CITES, but also any of its provisions. The exchange of information of a scientific or technical nature is simply indicated as an example for such a recommendation. Moreover, the provision does not restrict the Secretariat in any way to whom the recommendations are proposed. Thus, no limitations to Parties are in particular foreseen, which provides an almost unlimited range of potential addressees as discretion to the CITES-Secretariat.

The CMS Secretariat has among its functions—such as already mentioned in connection with publications—solely a very passive one without much discretion regarding recommendations (see Art. IX/4/i CMS). No own recommendations are foreseen on behalf of the Secretariat, but only the maintenance and publication of certain recommendation by the COPs. Art. 24 CBD does not refer itself to recommendations at all.

3.9. Discretion Regarding Internal and/or External Relations

Only the two conventions later opened for signature (CMS, CBD) contain norms explicitly pointing at internal and/or external relations through the Secretariat. The earlier signed one among these two conventions, the CMS, seems to provide more discretion to its Secretariat—in comparison to the CBD—in particular regarding the manner and addressees of these relations (see in detail Art. IX/4/b CMS in comparison with Art. 24/1/d CBD).

Concerning the manner of relations, the CMS uses the verbs “to maintain liaison and to promote liaison”. This indicates any form of connection, relation, contact, cooperation, and coordination. While the CBD restricts the Secretariat to “coordination” which can be reduced to a purely formal and procedural function. This correlates well also with the simple “postbox” function laid down for the CBD Secretariat when it comes to contacting executive bodies of other conventions through the COP (see Art 23/4/h CBD according to which “the Conference of Parties….shall ….(h) contact, through the Secretariat, the executive bodies of conventions dealing with matters covered by this Convention with a view to establishing appropriate forms of cooperation with them; and…” which seems to partly pre-determine the work of the Secretariat and reduces its discretion). Another difference is that that the CMS norm covers two more stakeholder groups which provides a wider mandate to the CMS-Secretariat.

3.10. Discretion Regarding Activities in Connection with AGREEMENTS (Only CMS)

The CMS is the only one of the three conventions compared which foresees the establishment of AGREEMENTS (Art. I/1/j: ““AGREEMENT” means an international agreement relating to the conservation of one or more migratory species as provided for in Articles IV and V of this Convention; and…”) under its aegis concluded by Parties (Art. II/3/c CMS and Art. IV/3 CMS) or non-Parties whereas the latter are at least range states of the species covered by the respective AGREEMENT (Art. V/2 CMS).

It lays down one particular function of the CMS-Secretariat related to these AGREEMENTS (the other two functions also mentioning AGREEMENTS (Art. IX/ b CMS and Art. IX/4/h CMS) could be more related to other types of function (internal/external relations and information provision) and have been already described above) which is the instruction to promote the conclusion of AGREEMENTS; the therein enshrined wide discretion of the Secretariat regarding means, space and time is in the same norm restricted, because it is put under the direction of the COP (see Art. IX/4/h CMS).

3.11. Discretion Regarding Activities in Connection with Protocols (Only CBD)

The CBD, is the only one of the three conventions compared which foresees the adoption of Protocols (Art. I/1/j: ““AGREEMENT” means an international agreement relating to the conservation of one or more migratory species as provided for in Articles IV and V of this Convention; and…”) through the COP (Art. 23/4/c CBD in connection with Art. 28 CBD). As mentioned, Art. 24/1/b CBD extends the functions of its Secretariat to performing the functions assigned to it by any Protocol.

The Cartagena Protocol and the Nagoya Protocol are the only protocols enforced, yet apply

mutatis mutandis the function of the Secretariat laid down in Art. 24/1 CBD (Art. 31/2 Cartagena Protocol; Art. 28/2 Nagoya Protocol; but see also the NagoyaKuala Lumpur Supplementary Protocol on Liability and Redress to the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety that entered into force on 5

th March 2018). Additionally, both Protocols provide for a rather passive function of the Secretariat (see for the Cartagena Protocol: Articles 11/1, 19/1, 19/2, 29/8 (with the exemption of Art. 19/3, Art. 29/6 and Art. 29/7, where some procedural, more active functions of the Secretariat are laid down) (available from

http://bch.cbd.int/protocol/text/; accessed 19 March 2019); see for the Nagoya Protocol: Articles 13/1, 13/4, 26/8 (with the exemption of Art. 13/5, Art. 26/6, Art. 26/7 where some information provision and meeting convening functions are laid down) (available from

https://www.cbd.int/abs/ text/default.shtml; accessed 19 March 2019).

4. Discussion

The following discussion starts with a semi-quantitative evaluation of the qualitative results obtained in the previous part. Afterwards some overall critical view points on the legislative techniques with regard to the formulation of the convention norms referring to functions are introduced. Afterwards some potential explanations of the formal differences among the conferences are discussed, while particularly referring to existing literature.

4.1. Comparison and Evaluation

This part offers a summarized semi-quantitative comparison and evaluation of the extent of discretion within the above prescribed Secretariats’ functions of the three conventions (

Table 2).

In formal terms, the number of explicitly prescribed functions as well as the extent of discretion is in summary largest within CITES, followed by CMS. The first impression formulated by the hypothesis above is therefore not only confirmed quantitatively, but also qualitatively. However, it was also already indicated that the function of the CBD secretariat could be—and obviously is, as will be shown later—more extensively interpreted.

4.2. Overall Viewpoints

Overall, CITES and CBD are not very precise in legal terms within their main Article when starting to lay down the functions of each respective Secretariat. Each of them begins the list expressing that the “functions shall be”. Thus, an enumerative and concluding list is expected from the norm in legal terms. But CITES as well as the CBD contain in other Articles further functions of the Secretariat. This kind of legislative technique does not make the task of comparison easier. However, the previous analyses of the functional clusters also tried to take into consideration other Articles of the respective Convention as such. Differently, Art. IX/4/k CMS refers in a legally more precise way to “any other function entrusted to it [the Secretariat] under this Convention or by the Conference of the Parties” and explicitly opens in this way the list of functions to be performed.

CITES demonstrates another particular rule-making technique in comparison to the other two conventions. It refers in the above mentioned list of functions to two other articles of the convention where functions are mentioned (Art. XII/2/b CITES refers to Art. XV and XVI). This would lead (again) to the assumption that the list of functions in Art. XII/2 CITES is complete and that other articles do not contain functions. This assumption is supported by the fact that a similar clause such as in Art. IX/4/k CMS –wherein a general reference is made to other functions laid down in the convention - does not exist in CITES. Nevertheless, a closer look into CITES proves different. Article XIII/1 and 2 CITES titled “International Measures” contains for example one active function of the Secretariat to inform Parties and one passive function of the Secretariat to receive information from one Party (and to obviously inform the other Parties) (Article XIII/1 and 2 CITES read such as following: “1. When the Secretariat in the light of information received is satisfied that any species included in Appendix I or II is being affected adversely by trade in specimens of that species or that the provisions of the present Convention are not being effectively implemented, it shall communicate such information to the authorized Management Authority of the Party or Parties concerned. 2. When any Party receives a communication as indicated in paragraph 1 of this Article, it shall, as soon as possible, inform the Secretariat of any relevant facts insofar as its laws permit and, where appropriate, propose remedial action. Where the Party considers that an inquiry is desirable, such inquiry may be carried out by one or more persons expressly authorized by the Party”).

In the cases of information sent to Parties, these functions might be also covered by the already cited Secretariats’ function “to invite the attention of the Parties to any matter pertaining to the aims of the present Convention.” (Art. XII/2/e CITES). Further active and passive functions are similarly laid down in additional articles of CITES (see Art. VIII/4/c: the possibility of a Management Authority to consult the Secretariat in order to facilitate certain decisions; Art. VIII/7: the right of the Secretariat to receive certain reports from the Parties; Article IX/3: receive information about Management and Scientific Authorities; Art. IX/4: the right to request information from the Management Authorities. Art. XI/1: the duty to call a meeting of the Conference of the Parties; Art. XI/7: the right to be informed by certain bodies and agencies (and—subject to certain conditions—to admit them to the COP as observers); Art. XVII/1: the duty to convene under certain conditions an extraordinary meeting of the Conference of Parties; Art. XVII/1: the duty to send out proposed amendments of the convention). Their coverage by the Art. XII CITES seems at least in some cases questionable.

4.3. Potential Explanations of the Formal Differences

Notwithstanding a further potential development of the functions of the CBD-Secretariat within the COP-Resolutions and Protocols (which to assess was not subject to this paper), the CBD-Secretariat shows itself to have been initially equipped with the least number of functions in comparison to CITES and CMS in the norms assessed (except regarding international cooperation).

This whole situation could be explained—but not justified—in particular with experience that the Parties acquired with earlier conventions.

Another reason adequate to explain the differences can be seen in the varying political origins and focuses of the different conventions. Thus, CITES was the product of a particular problem (illegal trade) and less politically negotiated prior to its opening for signature [

14,

39]. While in particular the CBD with its broader and less focused direction on specific problems can be seen as the result of a much more intensive political discussion forum where the fewer functions remaining in the CBD were the outcome of a long term search for compromises. The focus of the CMS is considerably broader, as well (in comparison to CITES). The CMS with its centering on future to be agreed upon AGREEMENTS—also indicated by three functions within the CMS referring to these instruments—is also a much more “evolutionary convention” than the straight-forward and single-pressure oriented CITES.

A further explanation for the lower number of formal functions laid down in the CBD (and also to lesser extent the CMS) in comparison to CITES can be derived from the number and content of the obligations to be implemented within these conventions. For the CBD it is indicated that it has only one concrete, three general and seven soft obligations (with CMS having 2/2/5 and CITES 6/1/2 respectively) (see [

11]], also on this differentiation of obligations). From the three conventions assessed it can be demonstrated that more and concrete secretariat functions correlate with a higher qualitative (and also to a lesser degree quantitative) extent of convention obligations for Parties to be dealt with by secretariats with higher active requirements.

4.4. Formal and Informal Viewpoints

Within a broader framework of policy mix analysis [

40] the current work summarized in

Table 2 can be considered to comparatively assess mixes of instruments and their consistency, their coherence and comprehensiveness as well as on policy making and its implementation.

The formal mandate, and therefore the content of the convention as instrument, of all the three convention secretariats assessed is limited in many regards and it is natural that it is limited. The comparative differences among these formal limitations and informal aspects of functions are the issues of high interest and are worthwhile to be further assessed.

Biermann and Bauer [

35] (p. 152) indicate the first of several structural variables for comparatively assessing the effectiveness of intergovernmental organizations in international environmental politics the formal competences as the following:

“(a) Formal competencies: The transfer in authority that states concede to an international organization varies considerably and might help explain variation in the effectiveness of the agency. For instance, some organizations are formally entitled to actively monitor regime compliance in member states while others depend on national reports of limited significance and reliability or, worse, have no means of monitoring at all. Such formal competencies matter significantly, and our research seems to indicate that an organization equipped with far-reaching formal competencies is likely to be more effective than an organization with little or no formal competencies.”

This statement is only partly supported by the results of this research. On the one hand, the CITES Secretariat with the most extended and substantial description of functions can execute for example particular influence through its given function to make recommendations (see on this quite effective function e.g., in [

41] and particular with regard to CITES [

34] (p. 8)) and to interact with all Parties. Thus, the allocation of functions of the three conventions do differ considerably and, thus are e.g., not in overall consistence with findings of [

38,

42]) who demonstrates large similarities in the allocation of mandates of the vast majority of treaty secretariats (however, even the formulations of [

38,

42] leave space for exemptions of this assumed large similarity and he might derive at this conclusion from a wider scope of assessment, including in particular the further functions contained in COP-resolutions).

On the other hand, activities are set by secretariats which are not formally mentioned in the legal framework such as to collect and disseminate scientific information (explicitly indicated by [

42] (p. 269) for the CBD-Secretariat as a main task while he points out the lack of the means and the mandate for scientific research). The collection and dissemination of such information could be interpreted as a preparatory part of “to service meetings of the Conference of the Parties” (Art. 24/1/a CBD) and the dissemination of SBSTTA-knowledge as part of the task to serve also SBSTTA.

This author also indicated “monitoring” as one function of this Secretariat [

38] (p. 260), [

6] (p. 266) while also citing one member of the Secretariat indicating that “governments do not want to be controlled….” [

38] (p. 269). Furthermore, although according to the wording of Art. 24/1/c CBD the Secretariat has to report to the COP on the execution of

its functions under this convention, but definitely reports also about malfunctions of Parties such as pledges not paid in time.

The CBD-Secretariat does not have explicit functional Articles on information sharing in the convention text contrary to CITES and CMS such as shown above and it was not primarily a capacity-building bureaucracy in the past [

42]. This changed considerably with the establishment of the Japanese Biodiversity Fund (on this fund see in particular

https://www.cbd.int/jbf/; accessed 19 March 2019) as an independent (non GEF-dependent) large-scale financial instrument enhancing the CBD-Secretariat’s efforts to support the Parties. This Fund allocates to the CBD-Secretariat funding to be used for numerous capacity-building events in particular on the National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans (on these activities see in particular

https://www.cbd.int/jbf/activities/nbsap/default.shtml, accessed 19 March 2019).

Despite the comparative difference of initial functions laid down in the initial mandate to the three conventions such as found in this study, this variety can be flattened or exaggerated depending in particular on extensions of the functions through resolutions of the COP.

One example of a function determined by the COP based on Art. 24/1/e CBD is that “the Secretariat has commissioned the drafting and publication of the Global Biodiversity Outlook (GBO), a report on the status and the policy measures to achieve the goals of the Convention.” [

38] (p. 264).

Thereby another correlation becomes pretty obvious. The more restrictive the functions are formulated, the more interpretative elbowroom needs to be searched for and be applied in order to allow a secretariat to execute basic functions assumed to be executed by each secretariat established by a multilateral environmental agreement. This correlates well with the findings by [

38] (p. 269); [

42] (p. 273) of considerable leeway given to the operations of the CBD-Secretariat due to a “very flexible” COP.

5. Conclusions

The paper concludes for the assessed main functional norms of the three conventions’ in formal terms that the number of explicitly prescribed functions as well as the extent of discretion is in summary largest within CITES, followed by CMS, and smallest within the CBD.

Some potential explanations for these formal differences could be located in the history of the creation of these conferences, their different focuses and the experiences of the Parties with conventions created earlier. Additionally, it seems that more and concrete secretariat functions correlate with a higher qualitative (and to a lesser degree also quantitative) extent of convention obligations for Parties to be dealt with by secretariats with higher activity requirements.

Another apparent correlation indicates that the more restrictively the functions are formulated in a qualitative and/or quantitative manner, the more interpretative elbowroom is searched for and applied if otherwise basic functions usually allocated to a Secretariat established by a MEA have not been clearly granted. However, the current study must be considered incomplete as it did not take into account a potential “big black box” (namely all the COP resolutions and in case of the CBD also the Protocols) potentially filled up with additional functions. Issues of any influence of the conventions analysed including their causality for potential improved implementation [

43] have neither been assessed regarding the functions.

However, such a snapshot comparing the initially laid down secretariats’ functions within three UN Environment-administered conventions can also (and hopefully does) shed scientific light on an interdisciplinary setting on the distribution of competences and power in international environmental politics and governance around multilateral environmental agreements.

Besides the structural variable of formal competences, the contextual variable of in how far formal competences of Secretariats are (very) widely interpreted by UN Environment and/or “flexible” COPs appears occasionally to be even more crucial.

The more the extensions of formal functions are not considered useful but influencing and even restricting the domain of the Parties, the less it is likely that a Secretariat can initiate or even uphold this extension of its formal competences in an informal manner.

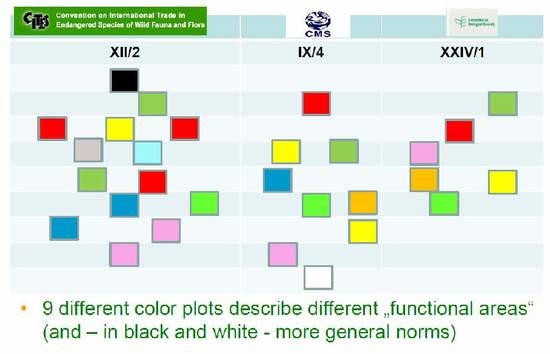

In summary, the results for the three conventions assessed are divided into nine functional areas and show an unexpected wide range of different functions in quality and quantity laid down in the conventions as well as extensive variety in the discretion for many of these functional areas. Some potential explanations for these formal differences are provided. The paper further finds that actually executed functions may not be fully covered by the underlying legal norms but by rather “flexible” highest governing bodies of MEAs and concludes that occasionally an unusual legislative style was chosen, and shows potential solutions and future research directions.