Personality Effects on the Endorsement of Ethically Questionable Negotiation Strategies: Business Ethics in Canada and China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Background and Hypothesis

2.1. Big Five Personality Traits and EQNS

2.2. Cultural Context and EQNS

3. Research Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Variablesand Procedure

4. Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 1. Promise that good things will happen to your opponent if he/she gives you what you want, even if you know that you cannot (or won’t) deliver these things when the other’s cooperation is obtained. |

| 2. Intentionally misrepresent information to your opponent in order to strengthen your arguments or position. |

| 3. Attempt to get your opponent fired from his/her position so that a new person will take his/her place. |

| 4. Intentionally misrepresent the nature of negotiations to your company in order to protect delicate discussions that have occurred. |

| 5. Gain information about an opponent’s negotiating position by paying your friends, associates, and contacts to get this information for you. |

| 6. Make an opening demand that is far greater than what you really hope to settle for. |

| 7. Convey a false impression that you are in absolutely no hurry to come to an agreement, thereby trying to put time pressure on your opponent to concede quickly. |

| 8. In order to get concessions from your opponent now, offer to make future concessions which you know you will not follow through on. |

| 9. Threaten to make your opponent look weak or foolish in front of a boss or others to whom he/she is accountable, even if you know that you won’t actually carry out the threat. |

| 10. Deny the validity of your opponent’s information that weakens your negotiating position, even though that information is true and valid. |

| 11. Intentionally misrepresent the progress of negotiations to your company in order to make your own position appear stronger. |

| 12. Talk directly to the people who your opponent reports to, or is accountable to, and tell them things that will undermine their confidence in your opponent as a negotiator. |

| 13. Gain information about an opponent’s negotiating position by cultivating his/her friendship through expensive gifts, entertaining or “personal favors.” |

| 14. Make an opening demand so high or so low that it seriously undermines your opponent’s confidence in his/her ability to negotiate a satisfactory agreement. |

| 15. Guarantee that your company will uphold the settlement reached, although you know that they will likely violate the agreement later. |

| 16. Gain information about an opponent’s negotiating position by trying to hire one of your opponent’s teammates (on the condition that the teammate will bring you confidential information with him/her). |

- I am the life of the party.

- I feel little concern for others.

- I am always prepared.

- I get stressed out easily.

- I have a rich vocabulary.

- I don’t talk a lot.

- I am interested in people.

- I leave my belongings around.

- I am relaxed most of the time.

- I have difficulty understanding abstract ideas.

- I feel comfortable around people.

- I insult people.

- I pay attention to details.

- I worry about things.

- I have a vivid imagination.

- I stay in the background.

- I sympathize with others’ feelings.

- I make a mess of things.

- I seldom feel blue.

- I am not interested in abstract ideas.

- I start conversations.

- I am not interested in other people’s problems.

- I get chores done right away.

- I am easily disturbed.

- I have excellent ideas.

- I have little to say.

- I have a soft heart.

- I often forget to put things back in their proper place.

- I get upset easily.

- I do not have a good imagination.

- I talk to a lot of different people at parties.

- I am not really interested in others.

- I like order.

- I change my mood a lot.

- I am quick to understand things.

- I don’t like to draw attention to myself.

- I take time out for others.

- I shirk my duties.

- I have frequent mood swings.

- I use difficult words.

- I don’t mind being the center of attention.

- I feel others’ emotions.

- I follow a schedule.

- I get irritated easily.

- I spend time reflecting on things.

- I am quiet around strangers.

- I make people feel at ease.

- I am exacting in my work.

- I often feel blue.

- I am full of ideas.

References

- Ma, Z. The SINS in Business Negotiations: Explore the Cross-Cultural Differences in Business Ethics Between Canada and China. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 91 (Suppl. 1), 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivers, C.; Lytle, A.L. Lying, cheating Foreigners!! Negotiation Ethics across Cultures. Int. Negot. 2007, 12, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, R.J.; Lewicki, R.J.; Donahue, E.M. Extending and testing a Five-Factor Model of ethical and unethical bargaining tactics: Introducing the SINS scale. J. Organ. Behav. 2000, 21, 649–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkema, R.J. Demographic, cultural, and economic predictors of perceived ethicality of negotiation behavior: A nine-country analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, B.; Friedman, R.A. Bargainer characteristics in distributive and integrative negotiation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, L. Negotiation Behavior and Outcomes: Empirical Evidence and Theoretical Issues. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 108, 515–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, R.S. Negotiating with Liars. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2007, 48, 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Volkema, R.J. A comparison of perceptions of ethical negotiation behavior in Mexico and the United States. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 1998, 9, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkema, R.J. Ethicality in negotiations: An analysis of perceptual similarities and differences between Brazil and the United States. J. Bus. Res. 1999, 45, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkema, R.J.; Fleury, M.T.L. Alternative negotiating conditions and the choice of negotiation tactics: A cross-cultural comparison. J. Bus. Ethics 2002, 36, 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Fallon, M.J.; Butterfield, K.D. A review of the empirical ethical decision-making literature. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 59, 375–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicki, R.J.; Robinson, R. Ethical and Unethical Bargaining Tactics: An Empirical Study. J. Bus. Ethics 1998, 17, 665–682. [Google Scholar]

- Lewicki, R.J.; Saunders, D.M.; Barry, B. Essentials of Negotiation, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill/Irwin: Boston, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, N.; Gundersen, A. International Dimensions of Organizational Behavior, 5th ed.; South-Western College Pub.: Boston, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z. The status of contemporary business ethics research: Present and future. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 90, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ip, P.K. Is Confucianism Good for Business Ethics in China? J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 88, 463–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, K.; Shi, G. Factors affecting ethical attitudes in mainland China and Hong Kong. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 77, 463–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, G.; Ma, Z.; Cao, J.; Zhang, H. A comparison of personal values of Chinese accounting practitioners and students. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 88 (Suppl. 1), 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghauri, P.; Fang, T. Negotiating with the Chinese: A social-cultural analysis. J. World Bus. 2001, 36, 303–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, E.T. Beyond Culture; Anchor: Garden City, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Kittler, M.G.; Rygl, D.; Mackinnon, A. Beyond culture or beyond control? Reviewing the use of Hall’s High-/Low-context concept. Int. J. Cross-Cult. Manag. 2011, 11, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banai, M.; Stefanidis, A.; Shetach, A.; Ozbek, M.F. Attitudes toward ethically questionable negotiation tactics: A two-country study. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 123, 669–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanidis, A.; Banai, M.; Richter, U. Attitudes towards questionable negotiation tactics in Peru. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 826–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alas, R. Ethics in countries with different cultural dimensions. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 69, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z. Conflict management styles as indicators of behavioral pattern in business negotiation: The impact of contextualism in two countries. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2007, 18, 260–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenbrunsel, A.; Smith-Crowe, K. Ethical decision making: Where we’ve been and where we’re going. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2008, 2, 545–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khatib, J.; Rawwas, M.; Swaidan, Z.; Rexeisen, R.J. The ethical challenges of global business-to-business negotiations: An empirical investigation of developing countries’ marketing managers’. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2005, 13, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banas, J.; Parks, M. Lambs among lions: The impact of ethical ideology on negotiation behaviors and outcomes. Int. Negot. 2002, 7, 235–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrick, M.R.; Mount, M.K. The Big Five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta-analysis’. Pers. Psychol. 1991, 44, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrick, M.R.; Mount, M.K.; Gupta, R. Meta-analysis of the relationship between the five-factor model of personality and Holland’s occupational types. Pers. Psychol. 2003, 56, 45–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digman, J.M.; Shmelyov, A.G. The structure of temperament and personality in Russian children. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 71, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G.; McCrae, R.R. Personality and culture revisited: Linking traits and dimensions of culture. Cross-Cult. Res. 2004, 38, 52–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R.R.; Coates, P.T. The structure of interpersonal traits: Wiggins’s circumflex and the Five-Factor Model. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 56, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.T., Jr.; McCrae, R.R. Solid ground in the wetland: A reply to Block. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, L.R. An alternative “description of personality”: The Big Five factor structure. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 59, 1216–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, J.J. Longitudinal stability of personality traits: A multitrait-multimethod-multioccasion analysis. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 49, 1266–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R.R. Why I advocate the Five-Factor Model: Joint factor analyses of the NEO-PI with other instruments. In Personality Psychology: Recent Trends and Emerging Directions; Buss, D.M., Cantor, N., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1989; pp. 237–245. [Google Scholar]

- Noller, P.; Law, H.; Comrey, A.L. Cattell, Comrey, and Eysenck personality factors compared: More evidence for the five robust factors. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 53, 775–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digman, J.M.; Inouye, J. Further specification of the five robust factors of personality. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 50, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waston, D. Stranger’s ratings of the five robust personality factors: Evidence of a surprising convergence with self-report. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 120–128. [Google Scholar]

- Aslam, M.S.; Mian, S.N. The impact of personality traits on academic dishonesty among Pakistan students. J. Commer. 2011, 3, 50–61. [Google Scholar]

- Kalshoven, K.; Den Hartog, D.N.; De Hoogh, A.H. Ethical leader behavior and big five factors of personality. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 100, 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moberg, D.J. The big five and organizational virtue. Bus. Ethics Q. 1999, 9, 245–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Jaeger, A. Getting to yes in China: Exploring individual differences in Chinese negotiation styles. Group Decis. Negot. 2005, 14, 415–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, J.; Burrill, D.; Gahagan, J. Social desirability, manifest anxiety, and social power. J. Soc. Psychol. 1969, 77, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.D.; Steele, M.W.; Tedeschi, J.J. Motivational correlates of strategy choices in the Prisoner’s Dilemma game. J. Soc. Psychol. 1969, 79, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, J.F.; Schul, P.L.; McCorkle, D. An assessment of selected relationships in a model of the industrial marketing negotiation process. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 1994, 14, 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z. Dispositional determinants of the endorsement of ethically questionable negotiation strategies: Evidence from West and East. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference for Promoting Business Ethics, London, UK, 4–16 August 2012. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, K.M.; Carnevale, P.J. A nasty but effective negotiation strategy: Misrepresentation of a common-value issue. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1997, 23, 504–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z.; Liang, D.; Chen, H. Negotiating with the Chinese: Are they more likely to use unethical strategies? Group Decis. Negot. 2013, 22, 641–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkbride, P.S.; Tang, F.Y.; Westwood, R.I. Chinese conflict preferences and pp. negotiating behavior: Cultural and psychological influence. Organ. Stud. 1991, 12, 365–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. The wording and translation of research instruments. In Field Methods in Cross-Cultural Research; Lonner, W.J., Berry, J.W., Eds.; Sage Publication: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1986; pp. 137–164. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z.; Wang, X.; Jaeger, A.; Anderson, T.; Wang, Y.; Saunders, D. Individual perception, bargaining behavior, and negotiation outcomes: A comparison across two countries. Int. J. Cross-Cult. Manag. 2002, 2, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Mean | s.d. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 1.44 | 0.50 | |||||||||||||

| 2. Age | 23.8 | 5.11 | 0.05 | ||||||||||||

| 3. Experience | 3.49 | 4.59 | −0.00 | 0.76 *** | - | ||||||||||

| 4. Emotional stability | 3.19 | 0.70 | −0.25 *** | 0.02 | 0.00 | (0.85) | |||||||||

| 5. Extraversion | 3.24 | 0.74 | −0.00 | 0.04 | −0.07 | 0.09 | (0.86) | ||||||||

| 6. Agreeableness | 3.74 | 0.59 | 0.21 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.23 * | 0.05 | 0.27 *** | (0.80) | |||||||

| 7. Conscientiousness | 3.49 | 0.56 | 0.20 ** | 0.30 *** | 0.29 ** | −0.06 | −0.04 | 0.27 *** | (0.76) | ||||||

| 8. Openness to experience | 3.61 | 0.54 | −0.13 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.16 * | 0.28 *** | 0.32 *** | 0.21 * | (0.75) | |||||

| 9. Traditional Competitive Bargaining | 2.78 | 0.88 | −0.12 | −0.15 ** | −0.19 * | 0.06 | −0.03 | −0.16 * | 0.11 | 0.18 * | (0.71) | ||||

| 10. Attacking the Opponent’s Network | 1.82 | 0.84 | −0.16 * | −0.05 | −0.21 * | −0.14 * | −0.00 | −0.37 *** | −0.14 * | −0.16 * | 0.25 *** | (0.73) | |||

| 11. False Promises | 1.96 | 0.91 | −0.13 | −0.15 * | −0.20 * | −0.09 | 0.02 | −0.36 *** | −0.14 * | −0.19 * | 0.25 *** | 0.66 *** | (0.74) | ||

| 12. Misrepresentation | 2.11 | 0.85 | −0.14 * | −0.15 * | −0.28 ** | −0.13 | −0.01 | −0.34 *** | −0.08 | −0.11 | 0.47 *** | 0.70 *** | 0.67 *** | (0.79) | |

| 13. Inappropriate Information Gathering | 2.41 | 1.07 | −0.24 *** | −0.07 | −0.22 * | −0.08 | −0.00 | −0.31 *** | −0.12 | −0.04 | 0.48 *** | 0.63 *** | 0.59 *** | 0.68 *** | (0.79) |

| Variables | Mean | s.d. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 1.54 | 0.50 | - | ||||||||||||

| 2. Age | 29.2 | 6.00 | −0.21 ** | - | |||||||||||

| 3. Experience | 5.44 | 5.76 | −0.10 | 0.90 *** | - | ||||||||||

| 4. Emotional stability | 3.11 | 0.63 | −0.06 | −0.02 | −0.02 | (0.72) | |||||||||

| 5. Extraversion | 3.21 | 0.52 | 0.12 | −0.23 ** | −0.14 | 0.14 | (0.65) | ||||||||

| 6. Agreeableness | 3.55 | 0.48 | 0.09 | −0.14 | −0.05 | 0.06 | 0.30 *** | (0.62) | |||||||

| 7. Conscientiousness | 3.50 | 0.55 | −0.06 | 0.23 ** | 0.26 *** | 0.19 * | 0.02 | 0.21 ** | (0.68) | ||||||

| 8. Openness to experience | 3.44 | 0.57 | −0.03 | −0.07 | −0.00 | −0.21 ** | 0.31 *** | 0.19 * | 0.20 * | (0.64) | |||||

| 9. Traditional Competitive Bargaining | 2.87 | 0.85 | −0.18 * | −0.11 | −0.19 * | −0.14 | −0.03 | −0.05 | −0.02 | 0.04 | (0.61) | ||||

| 10. Attacking the Opponent’s Network | 2.49 | 0.80 | −0.21 ** | 0.07 | 0.01 | −0.22 ** | −0.19 * | −0.33 *** | −0.13 | −0.08 | 0.45 *** | (0.61) | |||

| 11. False Promises | 2.40 | 0.90 | −0.07 | −0.21 ** | −0.21 ** | −0.21 ** | −0.09 | −0.15 | −0.06 | −0.06 | 0.45 *** | 0.48 *** | (0.72) | ||

| 12. Misrepresentation | 2.42 | 0.74 | −0.08 | −0.17 * | −0.20 ** | −0.18 * | −0.06 | −0.22 ** | −0.16 * | −0.11 | 0.53 *** | 0.64 *** | 0.66 *** | (0.61) | |

| 13. Inappropriate Information Gathering | 2.95 | 0.99 | −0.11 | −0.15 | −0.17 * | −0.18 * | −0.03 | −0.08 | −0.08 | 0.02 | 0.63 *** | 0.42 *** | 0.56 *** | 0.56 *** | (0.74) |

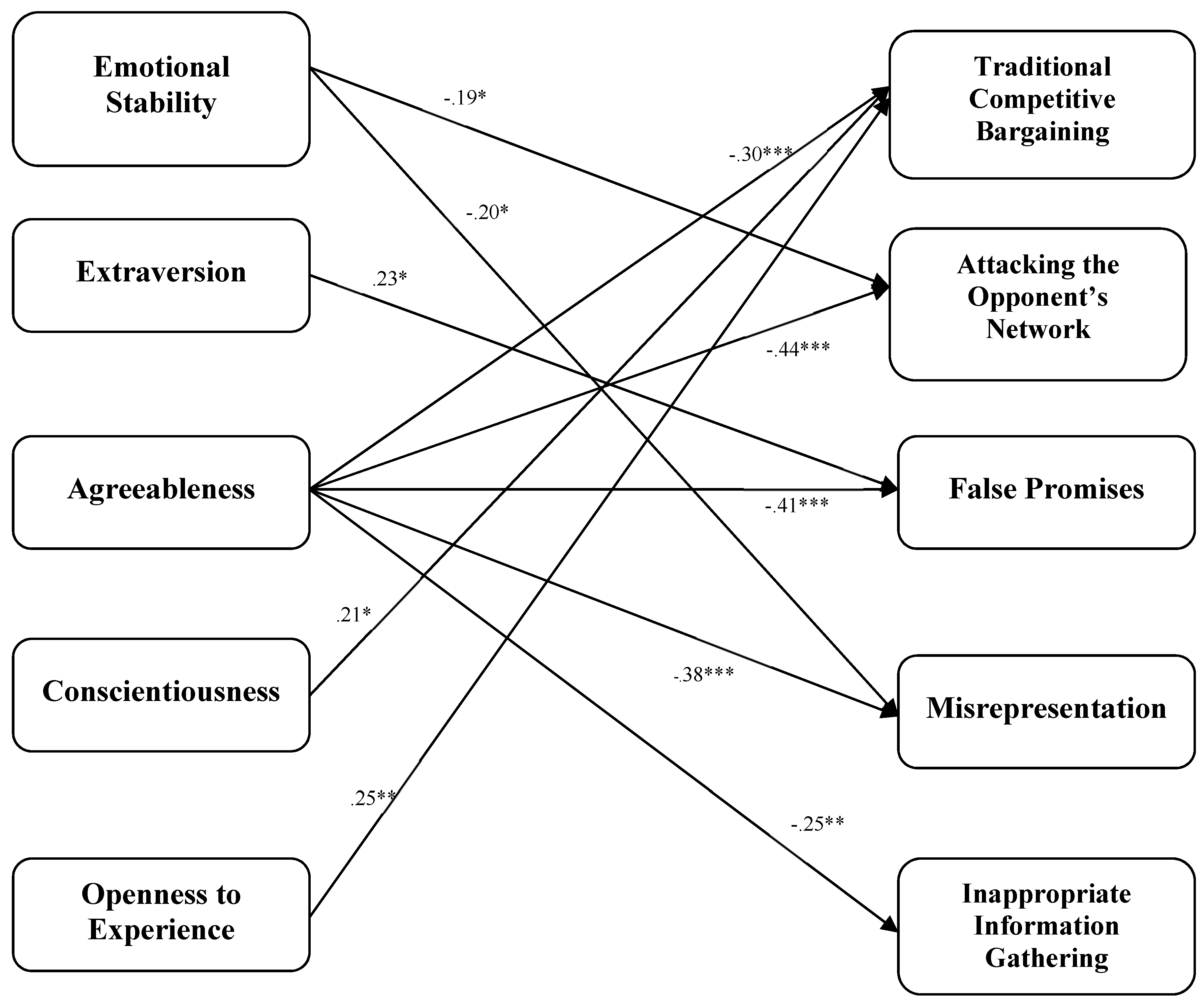

| Traditional Competitive Bargaining | Attacking the Opponent’s Network | False Promises | Misrepresentation | Inappropriate Info Gathering | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.37 *** | 0.13 | 0.07 | −0.18 | 0.04 |

| Gender | −0.11 | −0.16 | −0.12 | −0.12 | −0.29 *** |

| Education | 0.13 | −0.13 | −0.21 * | 0.08 | 0.03 |

| Experience | 0.05 | −0.17 | −0.15 | −0.06 | −0.18 |

| Emotional Stability | −0.08 | −0.19 * | −0.13 | −0.20 * | −0.13 |

| Extraversion | −0.06 | 0.10 | 0.23 * | 0.09 | 0.07 |

| Agreeableness | −0.30 *** | −0.44 *** | −0.41 *** | −0.38 *** | −0.25 ** |

| Conscientiousness | 0.21 * | −0.07 | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.12 |

| Openness to Experience | 0.25 ** | −0.05 | −0.10 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| R2 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.22 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.19 |

| F Value | 6.76 *** | 7.93 *** | 6.71 *** | 6.88 *** | 6.17 *** |

| Standard Errors | 0.87 | 0.71 | 0.80 | 0.76 | 0.99 |

| Traditional Competitive Bargaining | Attacking the Opponent’s Network | False Promises | Misrepresentation | Inappropriate Info Gathering | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.22 | 0.21 | −0.21 | −0.01 | −0.04 |

| Gender | −0.17 * | −0.16 | −0.10 | −0.06 | −0.12 |

| Education | 0.03 | −0.10 | −0.02 | −0.05 | 0.03 |

| Experience | −0.36 * | −0.20 | −0.01 | −0.18 | −0.14 |

| Emotional Stability | −0.18 * | −0.19 * | −0.21 ** | −0.17 * | −0.23 ** |

| Extraversion | 0.03 | −0.05 | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.02 |

| Agreeableness | −0.04 | −0.31 *** | −0.19 * | −0.24 ** | −0.11 |

| Conscientiousness | 0.03 | −0.04 | 0.06 | −0.08 | −0.06 |

| Openness to Experience | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.03 |

| R2 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.08 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.05 |

| F Value | 3.16 ** | 6.10 *** | 3.59 *** | 3.45 ** | 2.67 * |

| Standard Errors | 0.81 | 0.73 | 0.85 | 0.70 | 0.97 |

| Traditional Competitive Bargaining | Attacking the Opponent’s Network | False Promises | Misrepresentation | Inappropriate Info Gathering | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.21 * | 0.15 | −0.09 | −0.15 | −0.05 |

| Gender | −0.18 ** | −0.15 ** | −0.13 * | −0.09 | −0.21 *** |

| Education | 0.16 * | −0.11 | −0.10 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Experience | 0.02 | −0.16 * | −0.11 | −0.07 | −0.14 |

| Country (dummy) | 0.10 | −0.29 *** | −0.25 *** | −0.22 ** | −0.29 *** |

| Emotional Stability | −0.15 * | −0.18 *** | −0.17 ** | −0.18 *** | −0.16 ** |

| Extraversion | 0.05 | 0.02 | −0.10 | 0.08 | 0.05 |

| Agreeableness | −0.19 *** | −0.35 *** | −0.25 *** | −0.33 *** | −0.19 ** |

| Conscientiousness | 0.09 | −0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.20 |

| Openness to Experience | 0.15 * | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.06 |

| R2 | 0.20 | 0.38 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.19 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.17 | 0.36 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.17 |

| F Value | 8.06 *** | 22.62 *** | 11.49 *** | 10.91 ** | 8.93 * |

| Standard Errors | 0.86 | 0.72 | 0.83 | 0.72 | 0.98 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, X.; Ma, Z.; Liang, D. Personality Effects on the Endorsement of Ethically Questionable Negotiation Strategies: Business Ethics in Canada and China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3097. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113097

Liu X, Ma Z, Liang D. Personality Effects on the Endorsement of Ethically Questionable Negotiation Strategies: Business Ethics in Canada and China. Sustainability. 2019; 11(11):3097. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113097

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Xiaoyi, Zhenzhong Ma, and Dapeng Liang. 2019. "Personality Effects on the Endorsement of Ethically Questionable Negotiation Strategies: Business Ethics in Canada and China" Sustainability 11, no. 11: 3097. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113097

APA StyleLiu, X., Ma, Z., & Liang, D. (2019). Personality Effects on the Endorsement of Ethically Questionable Negotiation Strategies: Business Ethics in Canada and China. Sustainability, 11(11), 3097. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113097