How to Make an Industry Sustainable during an Industry Product Harm Crisis: The Role of a Consumer’s Sense of Control

Abstract

:1. Introduction

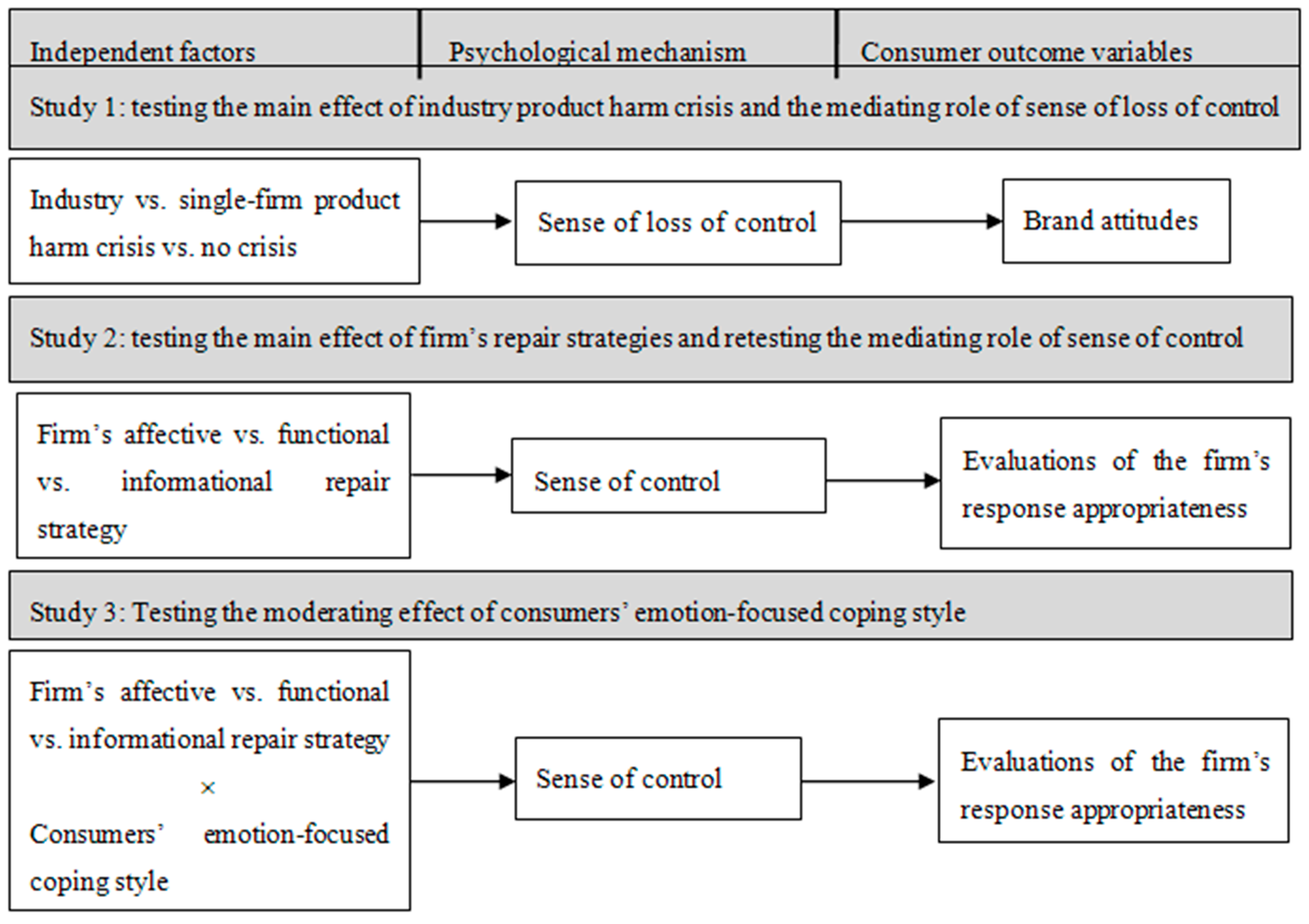

2. Conceptualization and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Industry Product Harm Crisis And Sense of Control

2.2. Repair Strategies and Restoring a Consumer’s Sense of Control

2.3. The Moderating Effect of Consumers’ Emotion-Focused Coping Style

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Study 1

3.1.1. Method

3.1.2. Results

3.2. Study 2

3.2.1. Pretest

3.2.2. Method

3.2.3. Results

3.3. Study 3

3.3.1. Method

3.3.2. Results

4. Discussions and Conclusions

4.1. Conclusions

4.2. Contributions

4.3. Research Limitations and Future Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Topaloglu, O.; Gokalp, O.N. How brand concept affects consumer response to product recalls: A longitudinal study in the US auto industry. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 88, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleeren, K.; Dekimpe, M.G.; van Heerde, H.J. Marketing research on product-harm crises: A review, managerial implications, and an agenda for future research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 593–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, C.A.; Rossi, C.A. Consumer reaction to product recalls: Factors influencing product judgement and behavioral intentions. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2007, 31, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Knight, J.G.; Zhang, H.; Mather, D.; Tan, L.P. Consumer scapegoating during a systemic product-harm crisis. J. Mark. Manag. 2012, 28, 1270–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. An Institutional Perspective of Consumer Behaviour in Industry-wide Crises. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, J.A.; Weary, G. Antecedents of causal uncertainty and perceived control: A prospective study. Eur. J. Pers. 1998, 12, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, E.A. A guide to constructs of control. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 71, 549–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutright, K.M.; Samper, A. Doing it the hard way: How low control drives preferences for high-effort products and services. J. Consum. Res. 2014, 41, 730–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, W.L. Image repair discourse and crisis communication. Public Relat. Rev. 1997, 23, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumstein, P.W.; Carssow, K.G.; Hall, J.; Hawkins, B.; Hoffman, R.; Ishem, E.; Maurer, C.P.; Spens, D.; Taylor, J.; Zimmerman, D.L. The honoring of accounts. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1974, 39, 551–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaney, J.R.; Benoit, W.L.; Brazeal, L.M. Blowout! Firestone’s image restoration campaign. Public Relat. Rev. 2002, 28, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, W.T. Protecting organization reputations during a crisis: The development and application of situational crisis communication theory. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2007, 10, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, W.T. Parameters for crisis communication. In the Handbook of Crisis Communication; Coombs, W.T., Holladay, S.J., Eds.; Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 2010; pp. 17–53. [Google Scholar]

- Susskind, J.; Maurer, K.; Thakkar, V.; Hamilton, D.L.; Sherman, J.W. Perceiving individuals and groups: Expectancies, dispositional inferences, and causal attributions. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 76, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Critcher, C.R.; Dunning, D. Predicting persons’ versus a person’s goodness: Behavioral forecasts diverge for individuals versus populations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 104, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Dawar, N.; Gürhan-Canli, Z. Base-rate information in consumer attributions of product-harm crises. J. Mark. Res. 2012, 49, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefcourt, H.M. The function of the illusions of control and freedom. Am. Psychol. 1973, 28, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutright, K.M.; Bettman, J.R.; Fitzsimons, G.J. Putting brands in their place: How a lack of control keeps brands contained. J. Mark. Res. 2013, 50, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, S.T.; Morling, B.; Stevens, L.E. Controlling self and others: A theory of anxiety, mental control, and social control. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1996, 22, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, P.H.; Ferrin, D.L.; Cooper, C.D.; Dirks, K.T. Removing the shadow of suspicion: The effects of apology versus denial for repairing competence-versus integrity-based trust violations. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 104–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutright, K.M. The beauty of boundaries: When and why we seek structure in consumption. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 38, 775–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critcher, C.R.; Dunning, D. Thinking about others versus another: Three reasons judgments about collectives and individuals differ. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2014, 8, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Meer, T.G.; Verhoeven, J.W. Emotional crisis communication. Public Relat. Rev. 2014, 40, 526–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawar, N.; Pillutla, M.M. Impact of product-harm crises on brand equity: The moderating role of consumer expectations. J. Mark. Res. 2000, 37, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, L.; Cameron, G.T. A relational approach examining the interplay of prior reputation and immediate response to a crisis. J. Public Relat. Res. 2004, 16, 213–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roschk, H.; Gelbrich, K. Identifying appropriate compensation types for service failures a meta-analytic and experimental analysis. J. Ser. Res. 2014, 17, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, M.K.; Bateson, J.E. Perceived control and the effects of crowding and consumer choice on the service experience. J. Consum. Res. 1991, 18, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, S.; Lazarus, R.S. If it changes it must be a process: Study of emotion and coping during three stages of a college examination. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 48, 150–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Duhachek, A.; Agrawal, N. Coping and Construal Level Matching Drives Health Message Effectiveness via Response Efficacy or Self-Efficacy Enhancement. J. Consum. Res. 2016, 43, 429–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, P.J. The emotion probe: Studies of motivation and attention. Am. Psychol. 1995, 50, 372–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craighead, C.W.; Karwan, K.R.; Miller, J.L. The effects of severity of failure and customer loyalty on service recovery strategies. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2004, 13, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romani, S.; Grappi, S.; Dalli, D. Emotions that drive consumers away from brands: Measuring negative emotions toward brands and their behavioral effects. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2012, 29, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Lai, I. The ethical judgment and moral reaction to the product-harm crisis: Theoretical model and empirical research. Sustainability 2016, 8, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.K.; Bolton, R.N. The effect of customers’ emotional responses to service failures on their recovery effort evaluations and satisfaction judgments. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2002, 30, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wanjek, L. How to fix a lie? The formation of Volkswagen’s post-crisis reputation among the German public. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2018, 21, 84–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A.D.; Cox, D.; Mantel, S.P. Consumer response to drug risk information: The role of positive affect. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veloutsou, C.; Moutinho, L. Brand relationships through brand reputation and brand tribalism. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkinaki, F.; Lunt, P. The effect of advertising message involvement on brand attitude accessibility. J. Econ. Psychol. 1999, 20, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, P.; Keenan, N.; Anders, S.; Perera, S.; Shallcross, S.; Hintz, S. Perceived past, present, and future control and adjustment to stressful life events. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 100, 749–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mroczek, D.K.; Kolarz, C.M. The effect of age on positive and negative affect: A developmental perspective on happiness. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 75, 1333–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Samaraweera, G.; Li, C.; Qing, P. Mitigating product harm crises and making markets sustainable: How does national culture matter? Sustainability 2014, 6, 2642–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Peng, S. How to repair customer trust after negative publicity: The roles of competence, integrity, benevolence, and forgiveness. Psychol. Mark. 2009, 26, 572–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, D.M.; Schmitt, M.T.; Branscombe, N.R.; Ellemers, N. Women’s reactions to ingroup members who protest discriminatory treatment: The importance of beliefs about inequality and response appropriateness. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 40, 733–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor-Smith, J.K.; Compas, B.E.; Wadsworth, M.E.; Thomsen, A.H.; Saltzman, H. Responses to stress in adolescence: Measurement of coping and involuntary stress responses. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2000, 68, 976–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Coombs, W.T.; Holladay, S.J. Further explorations of post-crisis communication: Effects of media and response strategies on perceptions and intentions. Public Relat. Rev. 2009, 35, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.F.; Kim, S. How organizations framed the 2009 H1N1 pandemic via social and traditional media: Implications for U.S. health communicators. Public Relat. Rev. 2011, 37, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roschk, H.; Kaiser, S. The nature of an apology: An experimental study on how to apologize after a service failure. Mark. Lett. 2013, 24, 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, K.; Boyd, D. Who should apologize when an employee transgresses? Source effects on apology effectiveness. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 130, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essau, C.A.; Trommsdorff, G. Coping with university-related problems: A cross-cultural comparison. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 1996, 27, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvera, D.H.; Meyer, T.; Laufer, D. Age-related reactions to a product harm crisis. J. Consum. Mark. 2012, 29, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| β Coefficient | t Ratio | |

|---|---|---|

| Posttest loss of control (control variable) | −0.424 ** | −5.181 |

| D1 | 0.081 | 0.837 |

| D2 | −0.087 | −0.904 |

| Emotion-focused coping | 0.079 | 0.511 |

| D1×emotion-focused coping | 0.312 ** | 2.642 |

| D2×emotion-focused coping | 0.068 | 0.526 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Q.; Wei, H.; Laufer, D. How to Make an Industry Sustainable during an Industry Product Harm Crisis: The Role of a Consumer’s Sense of Control. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3016. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113016

Li Q, Wei H, Laufer D. How to Make an Industry Sustainable during an Industry Product Harm Crisis: The Role of a Consumer’s Sense of Control. Sustainability. 2019; 11(11):3016. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113016

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Qing, Haiying Wei, and Daniel Laufer. 2019. "How to Make an Industry Sustainable during an Industry Product Harm Crisis: The Role of a Consumer’s Sense of Control" Sustainability 11, no. 11: 3016. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113016

APA StyleLi, Q., Wei, H., & Laufer, D. (2019). How to Make an Industry Sustainable during an Industry Product Harm Crisis: The Role of a Consumer’s Sense of Control. Sustainability, 11(11), 3016. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113016