Community-Based Tourism as a Sustainable Direction in Destination Development: An Empirical Examination of Visitor Behaviors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Community-Based Tourism Performance and Its Role

2.2. Behavioral Intentions

2.3. Sense of Belonging and Its Role

3. Methods

3.1. Measures and Questionnaire Development

3.2. Data Collection Procedure and Samples

4. Results

4.1. Data Quality Testing

4.2. Evaluation of the Higher-Order Framework and Modeling Comparison

4.3. Test for the Hypothesized Relationships

4.4. Test for Metric Invariance

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Local culture |

|

|

| Local entertainments |

|

|

| Local people |

|

|

|

| Local natural environment |

|

|

|

| Local superstructure |

|

|

| Local food and dishes |

|

| Local product |

|

|

|

| Local accommodation |

|

|

|

| Revisit intention |

|

|

| Word-of-mouth intention |

|

|

| Sense of belonging |

|

References

- Hwang, J.; Choi, J. An investigation of passengers’ psychological benefits from green brands in an environmentally friendly airline context: The moderating role of gender. Sustainability 2018, 10, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiatkawsin, K.; Han, H. Young travelers’ intention to behavior pro-environmentally: Merging the value-belief-norm theory and the expectancy theory. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilnoppakun, A.; Ampavat, K. Is Pai a sustainable tourism destination? Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 39, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melissen, F.; Cavagnaro, E.; Damen, M.; Düweke, A. Is the hotel industry prepared to face the challenge of sustainable development? J. Vac. Mark. 2015, 22, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Han, H. Effect of environmental perceptions on bicycle travelers’ decision-making process: Developing an extended model of goal-directed behavior. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 21, 1184–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boley, B.B.; McGehee, N.G.; Hammett, A.L.T. Importance-performance analysis (IPA) of sustainable tourism initiatives: The resident perspective. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, R.; Ali, A.; Galaski, K. Mobilizing knowledge: Determining key elements for success and pitfalls in developing community-based tourism. Curr. Iss. Tour. 2018, 21, 1547–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemelin, R.H.; Koster, R.; Youroukos, N. Tangible and intangible indicators of successful aboriginal tourism initiatives: A case study of two successful aboriginal tourism lodges in Northern Canada. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.H.; Tseng, C.H.; Lin, Y.F. Segmentation by recreation experience in island-based tourism: A case study of Taiwan’s Liuqiu island. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 362–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolkach, D.; King, B. Strengthening community-based tourism in a new resource-based island nation: Why and how? Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 386–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrväinen, L.; Uusitalo, M.; Silvennoinen, H.; Hasu, E. Towards sustainable growth in nature-based tourism destinations: Clients’ views of land use options in Finnish Lapland. Landsc. Urb. Plan. 2014, 122, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakata, H.; Prideaux, B. An alternative approach to community-based ecotourism: A bottom-up locally initiated non-monetised project in Papua New Guinea. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 880–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, B.; Lee, S.; Han, H. Consequences of cruise line involvement: A comparison of first-time and repeat passengers. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 1658–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S. Role of motivations for luxury cruise traveling, satisfaction, and involvement in building traveler loyalty. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 70, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.-H. Can community-based tourism contribute to sustainable development? Evidence from residents’ perceptions of the sustainability. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.H.; Yang, C.C. Conceptualizing and measuring environmentally responsible behaviors from the perspective of community-based tourists. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 454–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayaka, M.; Croy, W.G.; Cox, J.W. A dimensional approach to community-based tourism: Recognising and differentiating form and context. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 74, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S. Community-based ecotourism: The significance of social capital. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 303–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottiar, Z.; Boluk, K.; Kline, C. The roles of social entrepreneurs in rural destination development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 68, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mtapuri, O.; Giampiccoli, A. Interrogating the role of the state and nonstate actors in community-based tourism ventures: Toward a model for spreading the benefits to the wider community. S. Afr. Geogr. J. 2013, 95, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, M.C. Community benefit tourism initiatives: A conceptual oxymoron? Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wearing, S.L.; Wearing, M.; McDonald, M. Understanding local power and interactional processes in sustainable tourism: Exploring village–tour operator relations on the kokoda track, Papua New Guinea. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Al-Ansi, A.; Olya, H.G.T.; Kim, W. Exploring halal-friendly destination attributes in South Korea: Perceptions and behaviors of Muslim travelers toward a non-Muslim destination. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitner, M.J.; Boons, B.H.; Tetreault, M.S. The service encounter: Diagnosing favorable and unfavorable incidents. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Satisfaction: A Behavioral Perspective on the Consumer, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, E.; Burns, L.D.; Francis, S.K. Gender differences in the dimensional structure of apparel shopping satisfaction among Korean consumers: The role of hedonic shopping value. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2004, 22, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Dec. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugini, M.; Bagozzi, R.P. The role of desires and anticipated emotions in goal-directed behaviors: Broadening and deepening the theory of planned behavior. Brit. J. Sol. Psychol. 2001, 40, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, H.; Ahn, K.; Petrick, J.F. An integrated model of festival revisit intentions: Theory of planned behavior and festival quality/satisfaction. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 818–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, G.H.; Chipuer, H.M.; Bramston, P. Sense of place amongst adolescents and adults in two rural Australian towns: The discriminating features of place attachment, sense of community and place dependence in relation to place identity. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.T. Memorable tourist experiences and place attachment when consuming local food. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 18, 536–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, M.V. Theory of attachment and place attachment. In Psychological Theories of Environmental Issues; Bonnes, M., Lee, T., Bonaiuto, M., Eds.; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK, 2003; pp. 137–170. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.C. Predicting tourist attachment to destinations. Ann. Tour. Res. 2001, 28, 229–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining place attachment: A tripartite organizing framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. The relations between natural and civic place attachment and pro-environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K.-P.; Peng, N.; Chen, A. Incorporating on-site activity involvement and sense of belonging into the Mehrabian-Russell model—The experiential value of cultural tourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 30, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, S.S.; Han, H. Luxury cruise travelers: Other customer perceptions. J. Travel. Res. 2015, 54, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.-P. Love and satisfaction driver persistent stickiness: Investigating international tourist hotel brands. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 16, 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, J.; Jang, S. “To compare or not to compare?”: Comparative appeals in destination advertising of ski resorts. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 10, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.M.C.; Wu, H.; Huang, L.M. The influence of place attachment on the relationship between destination attractiveness and environmentally responsible behavior for island tourism in Penghu, Taiwan. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 1166–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, J. Relationships among Senior Tourists’ Perceptions of Tour Guides’ Professional Competencies, Rapport, Satisfaction with the Guide Service, Tour Satisfaction, and Word of Mouth. J. Travel. Res. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.; Han, H. Destination attributes influencing Chinese travelers’ perceptions of experience quality and intentions for island tourism: A case of Jeju Island. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 28, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smaldone, D.; Harris, C.; Sanyal, N. The role of time in developing place meanings. J. Leis. Res. 2008, 40, 479–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 600–638. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-García, J.; Durán-Sánchez, A.; del Río-Rama, M. Scientific coverage in community-based tourism: Sustainable tourism and strategy for social development. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Hours Worked (Indicator). Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/employment/hours-worked/indicator/english_47be1c78-en (accessed on 15 May 2019).

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Suicide Rates (Indicator). Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/suicide-rates/indicator/english_a82f3459-en (accessed on 15 May 2019).

- Al-Ansi, A.; Olya, H.G.; Han, H. Effect of general risk on trust, satisfaction, and recommendation intention for halal food. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, L. Influence of sustainable development by tourists’ place emotion: Analysis of the multiply mediating effect of attitude. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | |

| (1) | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| (2) | 0.584 a (0.341 b) | 1.000 | |||||||||

| (3) | 0.470 (0.221) | 0.453 (0.205) | 1.000 | ||||||||

| (4) | 0.446 (0.199) | 0.411 (0.169) | 0.405 (0.164) | 1.000 | |||||||

| (5) | 0.445 (0.198) | 0.428 (0.183) | 0.353 (0.125) | 0.428 (0.183) | 1.000 | ||||||

| (6) | 0.413 (0.171) | 0.315 (0.099) | 0.438 (0.192) | 0.411 (0.169) | 0.446 (0.199) | 1.000 | |||||

| (7) | 0.388 (0.151) | 0.385 (0.148) | 0.440 (0.194) | 0.385 (0.148) | 0.369 (0.136) | 0.629 (0.396) | 1.000 | ||||

| (8) | 0.434 (0.188) | 0.404 (0.163) | 0.398 (0.158) | 0.396 (0.157) | 0.366 (0.134) | 0.505 (0.255) | 0.541 (0.293) | 1.000 | |||

| (9) | 0.394 (0.155) | 0.388 (0.151) | 0.378 (0.143) | 0.493 (0.243) | 0.346 (0.120) | 0.387 (0.150) | 0.402 (0.162) | 0.470 (0.221) | 1.000 | ||

| (10) | 0.407 (0.166) | 0.373 (0.139) | 0.394 (0.155) | 0.490 (0.240) | 0.0351 (0.123) | 0.419 (0.176) | 0.384 (0.147) | 0.360 (0.130) | 0.582 (0.339) | 1.000 | |

| (11) | 0.446 (0.199) | 0.410 (0.168) | 0.459 (0.211) | 0.508 (0.258) | 0.380 (0.144) | 0.418 (0.175) | 0.370 (0.137) | 0.418 (0.175) | 0.562 (0.316) | 0.819 (0.671) | 1.000 |

| Mean (SD) | 4.699 (1.041) | 4.465 (1.157) | 4.770 (1.072) | 4.933 (1.136) | 5.016 (1.267) | 4.783 (1.174) | 4.356 (1.179) | 4.523 (1.072) | 4.232 (1.226) | 5.204 (1.269) | 5.297 (1.229) |

| CR (AVE) | 0.748 (0.501) | 0.805 (0.582) | 0.828 (0.616) | 0.809 (0.585) | 0.884 (0.793) | 0.879 (0.708) | 0.803 (0.671) | 0.772 (0.532) | 0.869 (0.689) | 0.887 (0.798) | 0.897 (0.814) |

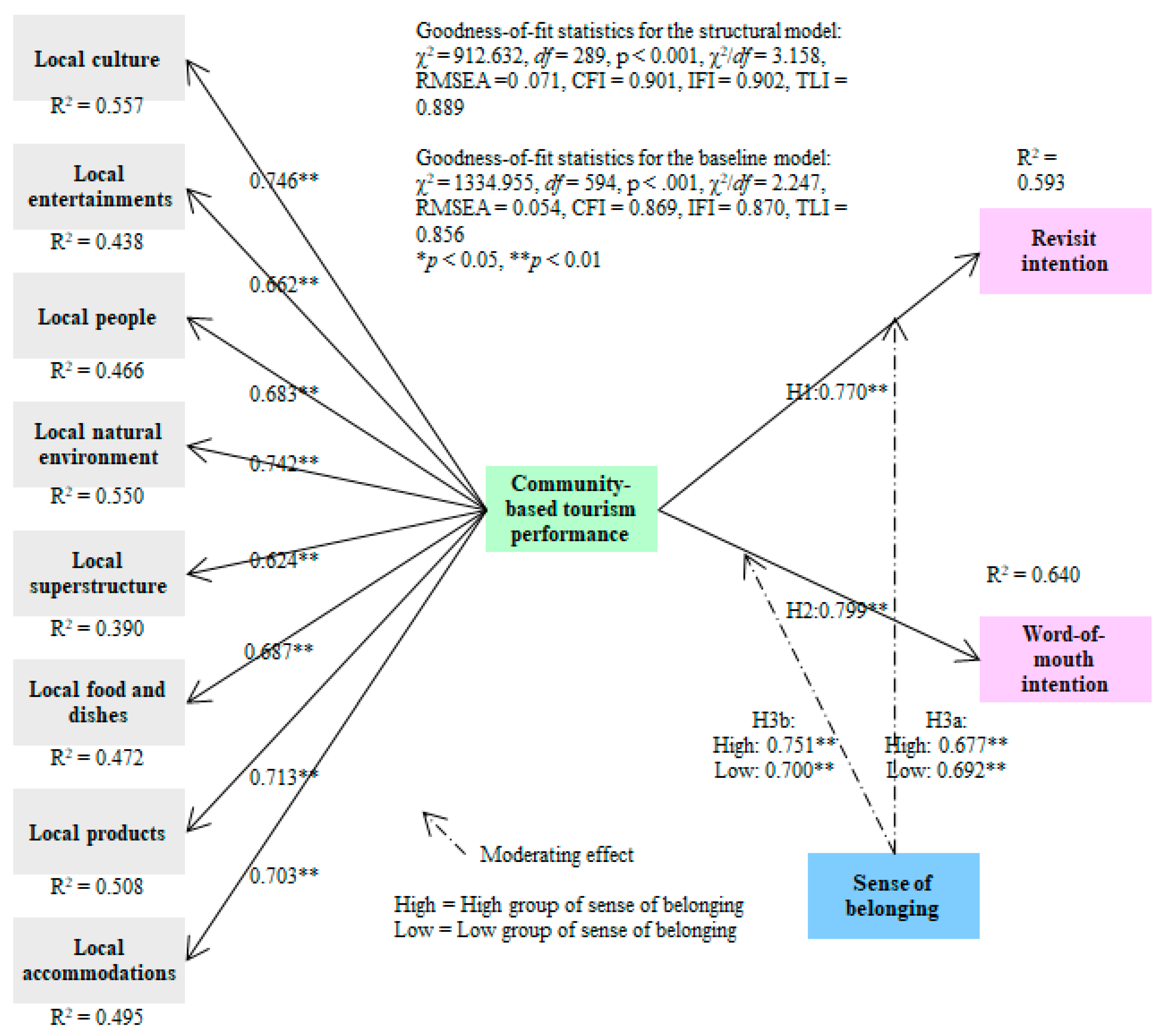

| Independent Variable | Dependent Variable | Standardized Estimate | t-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Community-based tourism performance | → | Revisit intention | 0.770 | 11.037 ** |

| H2 | Community-based tourism performance | → | Word-of-mouth intention | 0.799 | 10.899 ** |

| Goodness-of-fit statistics for the structural model: χ2 = 912.632, df = 289, p < 0.001, χ2/df = 3.158, RMSEA = 0.071, CFI = 0.901, IFI = 0.902, TLI = 0.889 | Total variance explained (R2): R2 for revisit intention = 0.593 R2 for word-of-mouth intention = 0.640 * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 | ||||

| Paths | High Group of Sense of Belonging (n = 269) | Low Group of Sense of Belonging (n = 159) | Baseline model (Freely Estimated) | Nested Model (Constrained to Be Equal) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficients | t-Values | Coefficients | t-Values | |||

| CBT perf. → Revisit intention | 0.677 | 8.003 ** | 0.692 | 5.990 ** | χ2 (594) = 1334.955 | χ2 (595) = 1338.746 a |

| CBT perf. → WOM intention | 0.751 | 6.139 ** | 0.700 | 7.787 ** | χ2 (594) = 1334.955 | χ2 (595) = 1339.223 b |

| Chi-square difference test: a Δχ2 (1) = 3.791, p > 0.05 (insignificant) (H3a was not supported) b Δχ2 (1) = 4.268, p < 0.05 (significant) (H3b was supported) | Goodness-of-fit statistics for the baseline model: χ2 = 1334.955, df = 594, p < 0.001, χ2/df = 2.247, RMSEA = 0.054, CFI = 0.869, IFI = 0.870, TLI = 0.856 * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 | |||||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Han, H.; Eom, T.; Al-Ansi, A.; Ryu, H.B.; Kim, W. Community-Based Tourism as a Sustainable Direction in Destination Development: An Empirical Examination of Visitor Behaviors. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2864. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102864

Han H, Eom T, Al-Ansi A, Ryu HB, Kim W. Community-Based Tourism as a Sustainable Direction in Destination Development: An Empirical Examination of Visitor Behaviors. Sustainability. 2019; 11(10):2864. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102864

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Heesup, Taeyeon Eom, Amr Al-Ansi, Hyungseo Bobby Ryu, and Wansoo Kim. 2019. "Community-Based Tourism as a Sustainable Direction in Destination Development: An Empirical Examination of Visitor Behaviors" Sustainability 11, no. 10: 2864. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102864

APA StyleHan, H., Eom, T., Al-Ansi, A., Ryu, H. B., & Kim, W. (2019). Community-Based Tourism as a Sustainable Direction in Destination Development: An Empirical Examination of Visitor Behaviors. Sustainability, 11(10), 2864. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102864