Food Heritagization and Sustainable Rural Tourism Destination: The Case of China’s Yuanjia Village

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Food and Rural Tourism

2.2. Food Heritagization and Sustainable Rural Tourism Development

3. Research Design

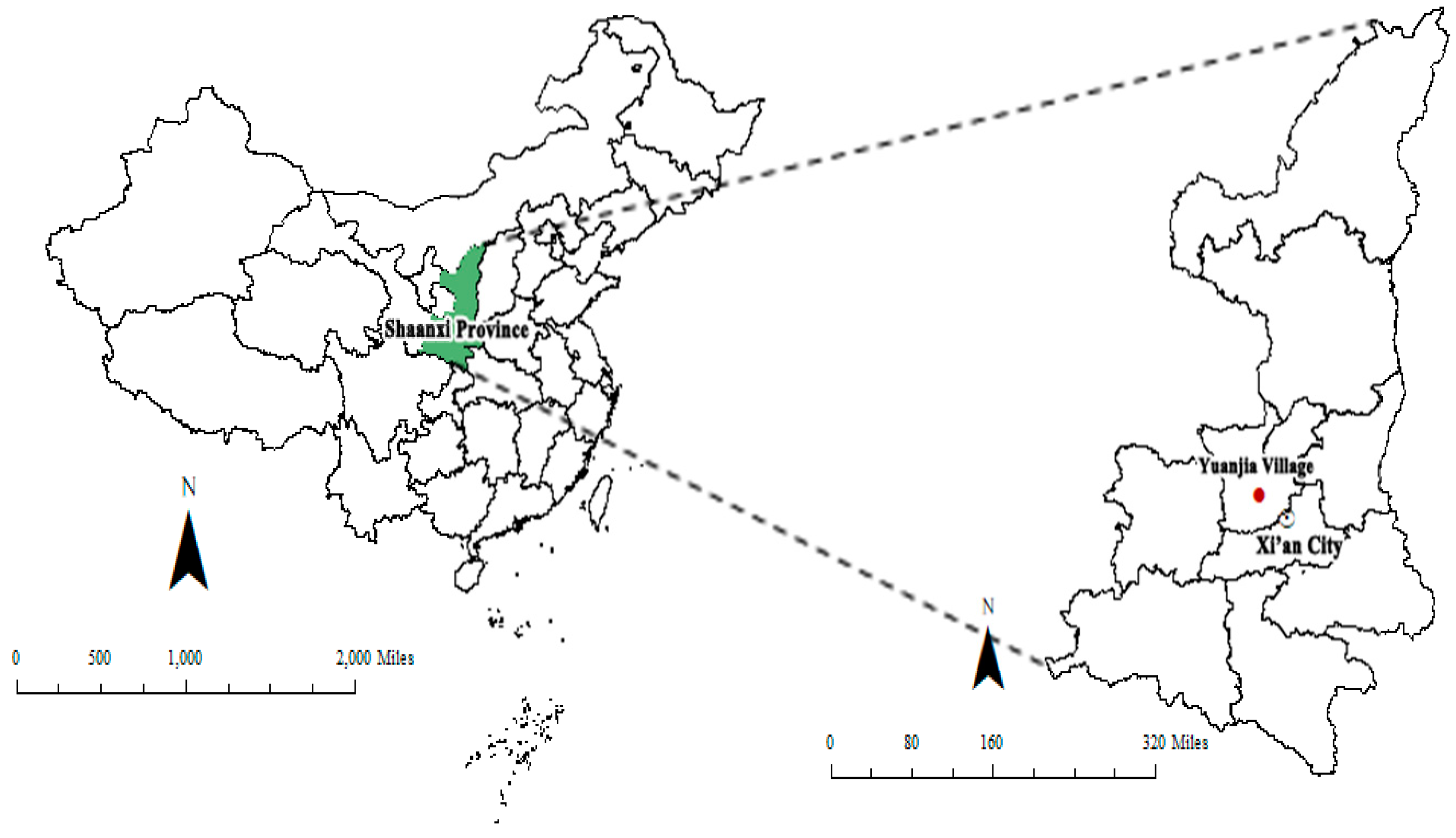

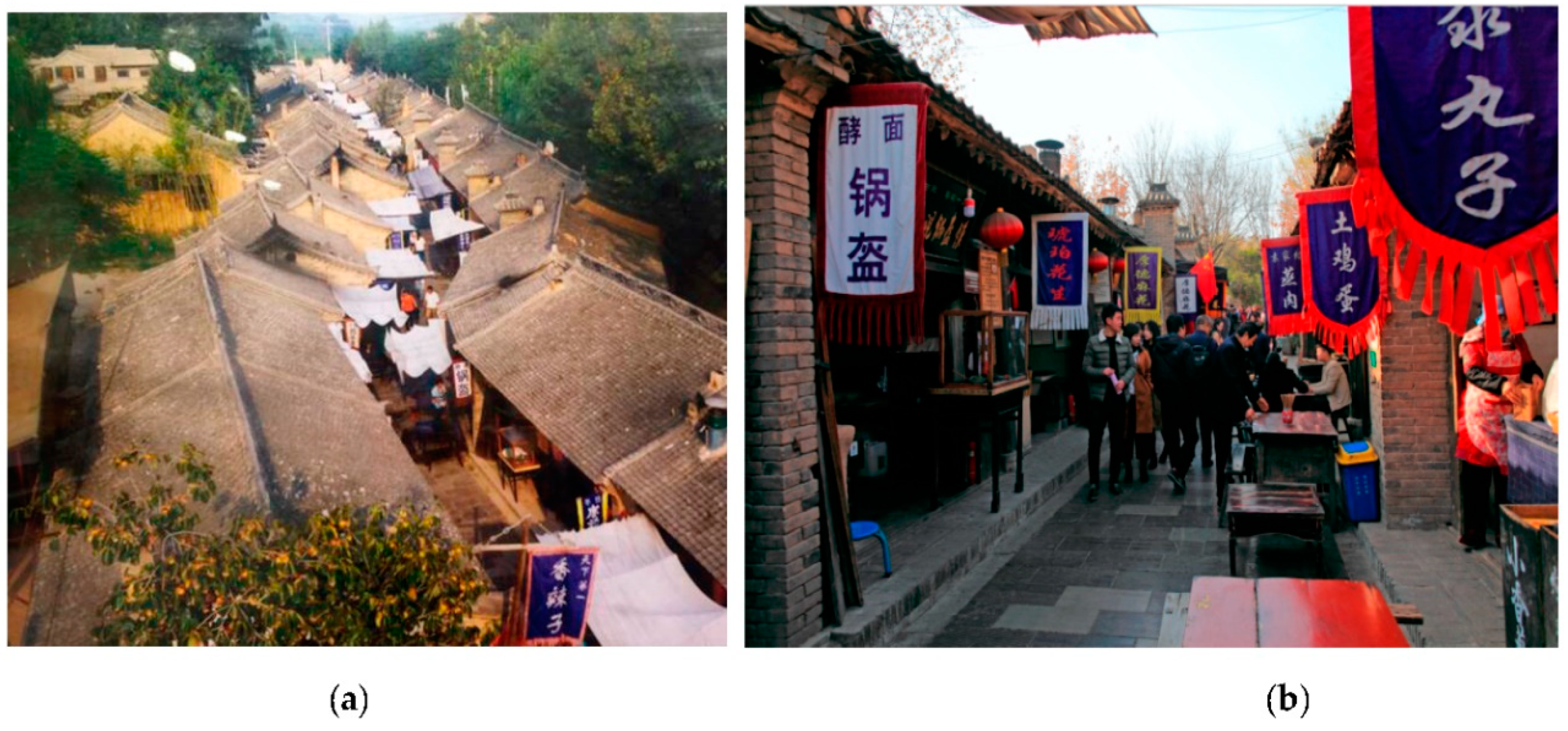

3.1. Research Context

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Findings

4.1. Food Heritagization on the Ground

4.1.1. The Initiative of Using Traditional Food as Attraction

4.1.2. Reproducing Traditional Food: Locals’ Perspective

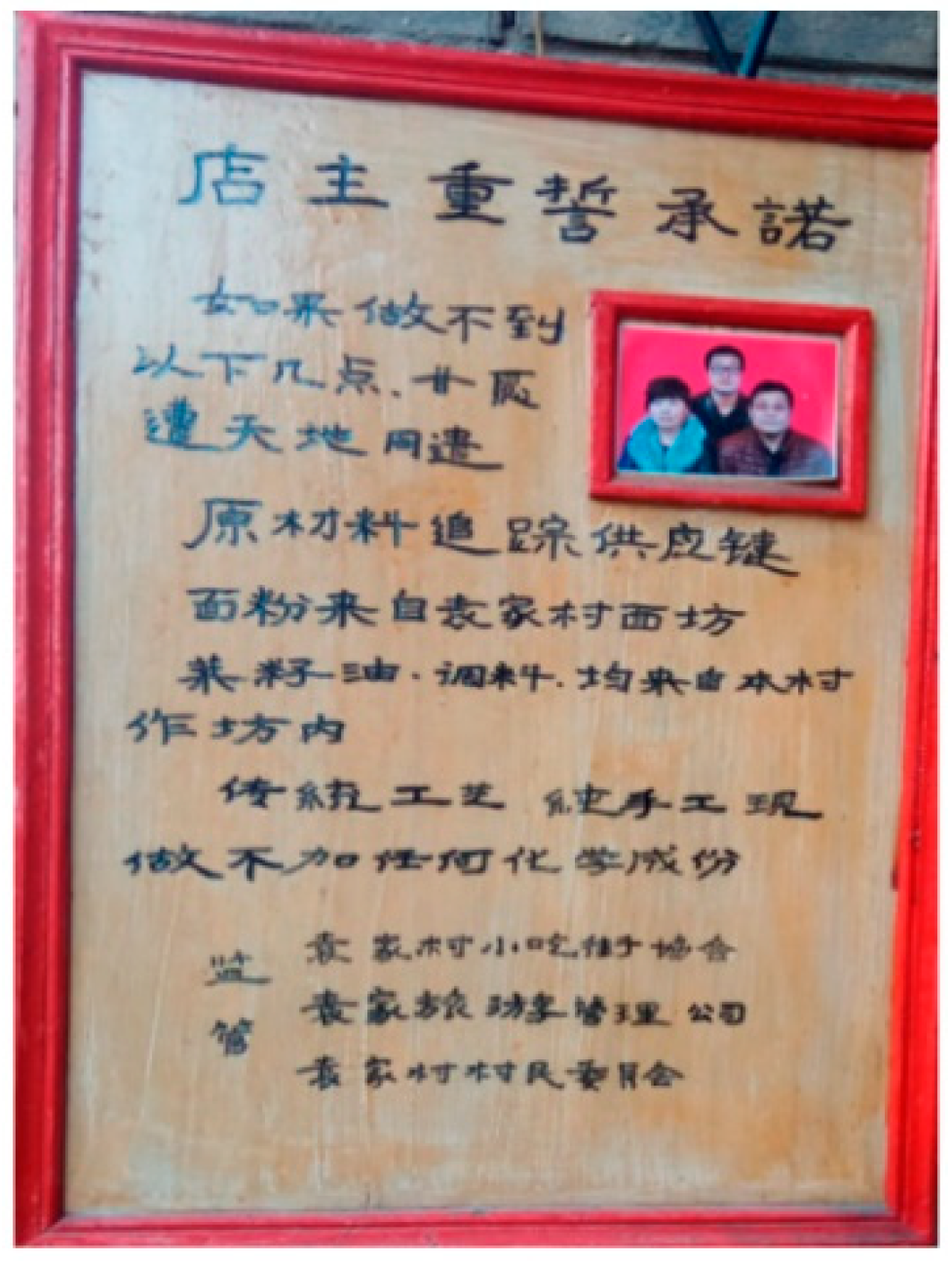

4.2. Bottom-Up Regulatory System of Traditional Food Reproduction

4.2.1. Daily Supervision of Food Quality by Village Committee

4.2.2. Supervision by Sector Association

4.2.3. Regulation of Local Authority

4.2.4. Peasants’ Moral Self-Discipline

4.3. Tourists’ Consumption of Traditional Food

4.4. Food Heritagization and the Formation of a Sustainable Rural Tourism Destination

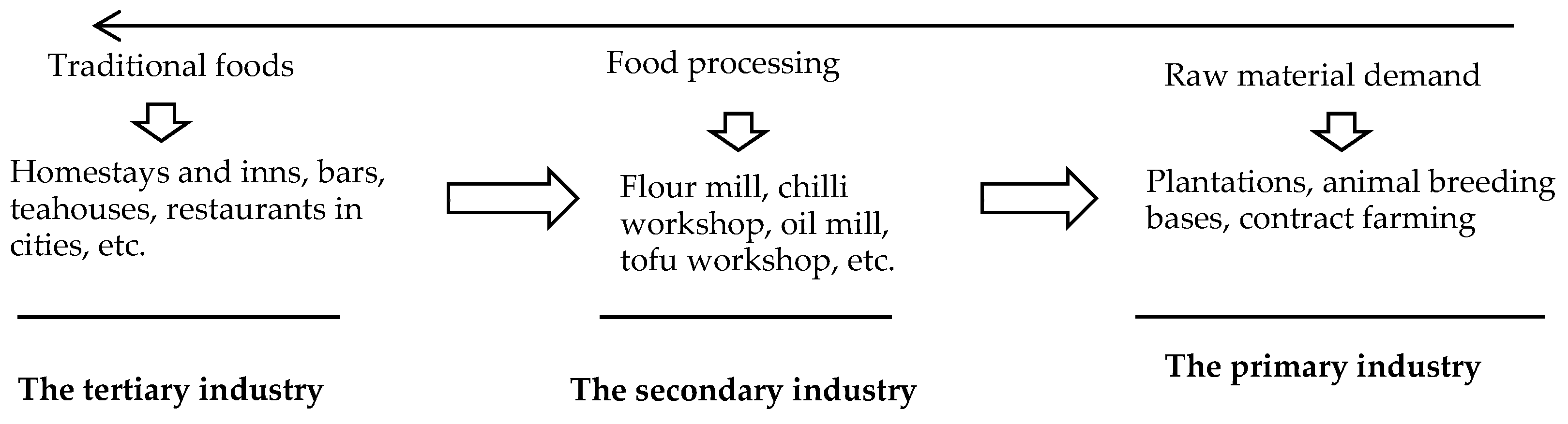

4.4.1. Industrial Convergence and Economic Sustainability

4.4.2. Village Governance and Social Sustainability

Cooperatives: Enhancing Economic Equity

Peasant School: Enhancing Social Harmony in a Moral Way

5. Discussion

6. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Note

References

- Okumus, B.; Xiang, Y.; Hutchinson, J. Local cuisines and destination marketing: Cases of three cities in Shandong, China. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 23, 584–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, S.; Wang, N. Towards a structural model of the tourist experience: An illustration from food experiences in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, J.A. Heritagizing local cheese in China: Opportunities, challenges, and inequalities. Food Foodways 2018, 26, 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.K.; Eves, A.; Scarles, C. Building a model of local food consumption on trips and holidays: A grounded theory approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, A.; Park, E.; Kim, S.; Yeoman, I. What is food tourism? Tour. Manag. 2018, 68, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, S. Production places or consumption spaces? The place-making agency of food tourism in Ireland and Scotland. Tour. Geogr. 2012, 14, 535–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J.; Ron, A.S. Understanding heritage cuisines and tourism: Identity, image, authenticity, and change. J. Heritage Tour. 2013, 8, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J. Heritage Cuisines: Traditions, Identities and Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bin, L.; Xing-Long, K.; Zhong-Nuan, C.; Tourism, S.O.; University, S.; & Tourism, D.O. Research on the tourist food consumption: A case study of chengdu. Hum. Geogr. 2017, 32, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Huang, R. Understanding the importance of food tourism to Chongqing, China. J. Vacat. Mark. 2016, 22, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, S.; De Master, K. New rural livelihoods or museums of production? Quality food initiatives in practice. J. Rural. Stud. 2011, 27, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X. The farmhouse joy (nongjiale) movement in China’s ethnic minority villages. Asia Pac. J. Anthr. 2014, 15, 158–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chee-Beng, T.; Yuling, D. The promotion of tea in South China: Re-inventing tradition in an old industry. Food Foodways 2010, 18, 121–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnis, E. Reimagining Marginalized Foods: Global Processes, Local Places; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.e.; Wang, L.; Zhong, L.; Cheng, S. A literature research on tourism food consumption. Prog. Geogr. 2017, 36, 513–526. [Google Scholar]

- Bessière, J. Local development and heritage: Traditional food and cuisine as tourist attractions in rural areas. Sociol. Rural. 1998, 38, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littaye, A. The role of the Ark of Taste in promoting pinole, a Mexican heritage food. J. Rural. Stud. 2015, 42, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L. Uses of Heritzage; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Grasseni, C. Of cheese and ecomuseums: Food as cultural heritage in the Northern Italian Alps. In Edible Identities: Food as Cultural Heritage; Brulotte, R.L., Giovine, M.A.D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Grasseni, C. Re-inventing food: Alpine cheese in the age of global heritage. Anthr. Food 2011, 8, 6819. [Google Scholar]

- Littaye, A.Z. The multifunctionality of heritage food: The example of pinole, a Mexican sweet. Geoforum 2016, 76, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisvoll, S.; Forbord, M.; Blekesaune, A. An empirical investigation of tourists’ consumption of local food in rural tourism. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2016, 16, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldacchino, G. Feeding the rural tourism strategy? Food and notions of place and identity. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2015, 15, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidali, K.L.; Kastenholz, E.; Bianchi, R. Food tourism, niche markets and products in rural tourism: Combining the intimacy model and the experience economy as a rural development strategy. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1179–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, S.; Aitchison, C. The role of food tourism in sustaining regional identity: A case study of Cornwall, South West England. J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, S.-W. The revival of traditional water buffalo cheese consumption: Class, heritage and modernity in contemporary China. Food Foodways 2014, 22, 322–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.-H. Nongjiale tourism and contested space in rural China. Mod. China 2014, 40, 519–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X. Agritainment in mountain villages as urban consumption space. J. East China Norm. Univ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2015, 47, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Blay-Palmer, A. Food Fears: From Industrial to Sustainable Food Systems; Ashgate Press: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Feagan, R. The place of food: Mapping out the ‘local’in local food systems. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2007, 31, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y. Food safety and social risk in contemporary China. J. Asian Stud. 2012, 71, 705–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Kerstetter, D.; Hunt, C. Tourism development and changing rural identity in China. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 66, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindholm, C. Culture and Authenticity; Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Thomé-Ortiz, H. Heritage cuisine and identity: Free time and its relation to the social reproduction of local food. J. Heritage Tour. 2018, 13, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.F.; Oya, C.; Ye, J. Bringing agriculture back in: The central place of agrarian change in rural China studies. J. Agrar. Chang. 2015, 15, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giovine, M.A. The everyday as extraordinary: Revitalization, religion, and the elevation of Cucina Casareccia to heritage cuisine in Pietrelcina, Italy. In Edible Identities: Food as Cultural Heritage; Brulotte, R.L., Giovine, M.A.D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 77–92. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, J.J.; Johnston, M.; Robertson, C.; Glidewell, L.; Entwistle, V.; Eccles, M.P.; Grimshaw, J.M. What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychol. Health 2010, 25, 1229–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G.J.; Zhao, Y.Q.; Sun, S.Z. Sustainable development mechanism of food culture’s translocal production based on authenticity. Sustainability 2014, 6, 7030–7047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Liu-Lastres, B.; Pennington-Gray, L.; Hu, X.; Liu, J. Industry convergence in rural tourism development: A China-featured term or a new initiative? Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M. What, then, is a Chinese peasant? Nongmin discourses and agroindustrialization in contemporary China. Agric. Hum. Values 2015, 32, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. A phenomenological explication of guanxi in rural tourism management: A case study of a village in China. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, T.; Zhou, Y. Community, governments and external capitals in China’s rural cultural tourism: A comparative study of two adjacent villages. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, A.F. The Peasant in Postsocialist China: History, Politics, and Capitalism; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, H. Study on the development of rural tourism and construction of rural residents’ interest- sharing mechanism: A case of the development of tourism industry in the northwest area of Haidian district, Beijing. Tour. Trib. 2012, 27, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, X. Competition and (in)equality: A case study of the family restaurants in a touristic Miao Village in Fenghuang County of Hunan, China. Tour. Trib. 2016, 31, 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, P.C. China’s new-age small farms and their vertical integration: Agribusiness or co-ops? Mod. China 2011, 37, 107–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Ryan, C.; Cave, J.; Zhang, C. Tourism border-making: A political economy of China’s border tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 76, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjalager, A.-M. Agricultural diversification into tourism: Evidence of a European community development programme. Tour. Manag. 1996, 17, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjalager, A.-M.; Johansen, P.H. Food tourism in protected areas–sustainability for producers, the environment and tourism? J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Gender | Age | Identity Information | No. | Gender | Age | Identity Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-01 | Male | 40+ | Party secretary of the village | T-01 | Male | 30+ | From Shaanxi |

| L-02 | Male | 50+ | Village elite | T-02 | Male | 40+ | From Shaanxi |

| L-03 | Male | 50+ | Chilli workshop owner; village elite | T-03 | Male | 40 | From Jiangsu |

| L-04 | Male | 50+ | Deputy director of the village committee | T-04 | Male | 30 | From Shaanxi |

| L-05 | Male | 34 | Deputy director of the village committee | T-05 | Male | 35+ | From Henan |

| L-06 | Male | 33 | Office director of the village committee | T-06 | Male | 30+ | From Shaanxi |

| L-07 | Male | 26 | Ordinary employee of the village | T-07 | Male | 40+ | From Shaanxi |

| L-08 | Female | 40+ | Vermicelli shopkeeper | T-08 | Male | 35+ | From Shaanxi |

| L-09 | Female | 50+ | Sheep blood soup shopkeeper | T-09 | Male | 30 | From Shaanxi |

| L-10 | Male | 45 | Tofu shopkeeper | T-10 | Female | 40+ | From Gansu |

| L-11 | Male | 50+ | Youtuotuo(a local snack) shopkeeper | T-11 | Female | 20+ | From Yunnan |

| L-12 | Male | 60+ | Sanzi(a local snack) shopkeeper | T-12 | Female | 35+ | From Sichuan |

| L-13 | Male | 33 | Handicraft shopkeeper | T-13 | Female | 26 | From Shaanxi |

| L-14 | Female | 30 | B&B owner | T-14 | Female | 30+ | From Shaanxi |

| L-15 | Male | 60+ | Ordinary villager | T-15 | Female | 25+ | From Henan |

| L-16 | Male | 60+ | Ordinary villager | T-16 | Female | 30+ | From Shaanxi |

| L-17 | Male | 40+ | Ordinary villager | T-17 | Female | 30 | From Shaanxi |

| L-18 | Female | 50+ | Ordinary villager | T-18 | Female | 24 | From Fujian |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guan, J.; Gao, J.; Zhang, C. Food Heritagization and Sustainable Rural Tourism Destination: The Case of China’s Yuanjia Village. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2858. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102858

Guan J, Gao J, Zhang C. Food Heritagization and Sustainable Rural Tourism Destination: The Case of China’s Yuanjia Village. Sustainability. 2019; 11(10):2858. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102858

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuan, Jing, Jun Gao, and Chaozhi Zhang. 2019. "Food Heritagization and Sustainable Rural Tourism Destination: The Case of China’s Yuanjia Village" Sustainability 11, no. 10: 2858. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102858

APA StyleGuan, J., Gao, J., & Zhang, C. (2019). Food Heritagization and Sustainable Rural Tourism Destination: The Case of China’s Yuanjia Village. Sustainability, 11(10), 2858. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102858