Exploring the Entrepreneurial Intentions of Science and Engineering Students in China: A Q Methodology Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Entrepreneurship and Entrepreneurial Intention

2.2. Entrepreneurship Education

2.3. Entrepreneurship Education in China

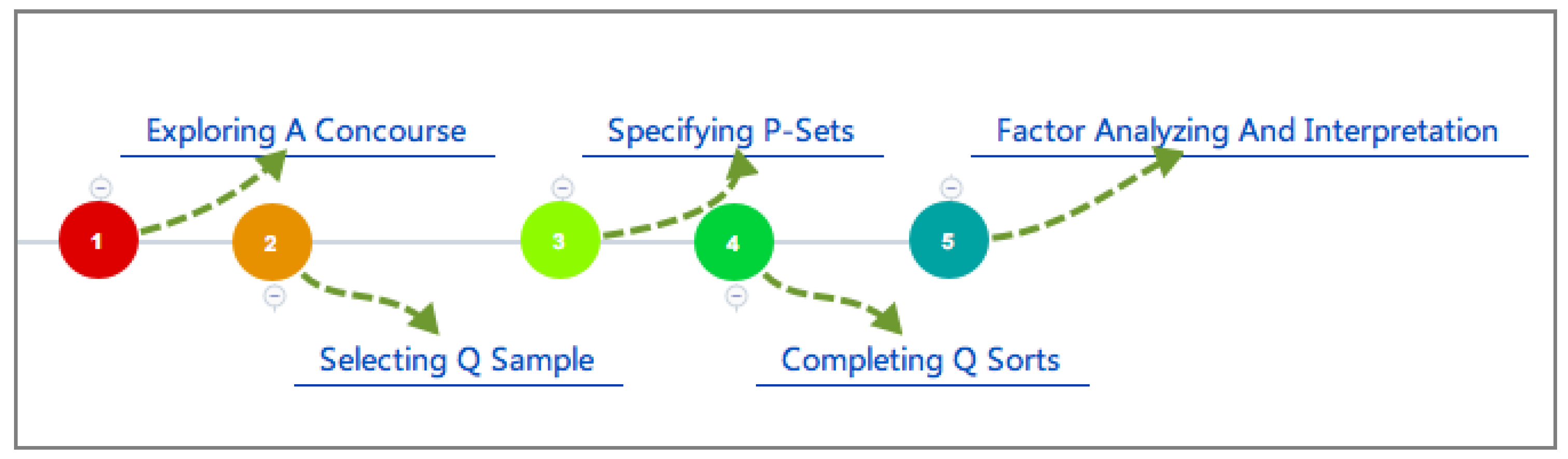

3. Methodology

3.1. Development of Concourse

3.2. Establishment of Q Sample

3.3. Selection of P-Sets

3.4. Q Sorting

3.5. Q Factor Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Factor A (Intellectual Entrepreneur)

4.2. Factor B (Opportunity-Driven Entrepreneur)

4.3. Factor C (Individualistic Entrepreneur)

4.4. Consensus Opinions between Factors A, B, and C

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schumpeter, J. The Creative Response in Economic History. J. Econ. Hist. 1947, 7, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giamartino, G.A.; McDougall, P.P.; Bird, B.J. International Entrepreneurship: The State of the Field. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1993, 18, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.H.; Webb, J.W.; Fu, J.; Singhal, S. A competency-based perspective on entrepreneurship education: Conceptual and empirical insights. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2013, 51, 352–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, P.D. Entrepreneurship in the United States: The Future is Now; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, B. Implementing Entrepreneurial Ideas: The Case for Intention. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1988, 13, 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, J.; Gartner, W.B. Properties of emerging organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1988, 13, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N.F.; Brazeal, D.V. Entrepreneurial potential and potential entrepreneurs. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1994, 18, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellingsen, I.T.; Størksen, I.; Stephens, P. Q methodology in social work research. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2010, 13, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N.F. The impact of prior entrepreneurial exposure on perceptions of new venture feasibility and desirability. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1993, 18, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Fayolle, A. A systematic literature review on entrepreneurial intentions: Citation, thematic analyses, and research agenda. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2015, 11, 907–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterbeek, H.; Van Praag, M.; Ijsselstein, A. The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurship skills and motivation. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2010, 54, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckertz, A.; Wagner, M. The influence of sustainability orientation on entrepreneurial intentions—Investigating the role of business experience. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 524–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploum, L.; Blok, V.; Lans, T.; Omta, O. Toward a validated competence framework for sustainable entrepreneurship. Organ. Environ. 2017, 31, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Gu, D.; Liang, C.; Zhao, S.; Lu, W. Fostering Sustainable Entrepreneurs: Evidence from China College Students’ “Internet Plus” Innovation and Entrepreneurship Competition (CSIPC). Sustainability 2018, 10, 3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, K.M.Y.; Breznik, K. Impacts of innovativeness and attitude on entrepreneurial intention: Among engineering and non-engineering students. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2016, 27, 683–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anna, M.V.; Kaisu, P.; Katharina, F. Drivers of entrepreneurial intentions in sustainable entrepreneurship. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018, 24, 359–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruett, M.; Shinnar, R.; Toney, B.; Llopis, F.; Fox, J. Explaining entrepreneurial intentions of university students: A cross-cultural study. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2009, 15, 571–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S.; Venkataraman, S. The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J.A. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, 3rd ed.; George Allen and Unwin: London, UK, 2008; pp. 132–134. [Google Scholar]

- Tajeddini, K.; Mueller, S. Entrepreneurial characteristics in Switzerland and the UK: A comparative study of techno-entrepreneurs. J. Int. Entrep. 2009, 7, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, P. Intention-behavior relations: A conceptual and empirical review. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 12, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Attitudes, Personality and Behavior, 2nd ed.; Open University Press: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Babnik, K.; Sirca, N.T. Knowledge creation, transfer and retention: The case of intergenerational cooperation. Int. J. Innov. Learn. 2014, 15, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Rodríguez-Cohard, J.C.; Rueda-Cantuche, J.M. Factors affecting entrepreneurial intention levels: A role for education. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2011, 7, 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapero, A.; Sokol, L. Social Dimensions of Entrepreneurship; Encyclopedia of entrepreneurship; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1982; pp. 72–90. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, E.R. Individual entrepreneurial intent: Construct clarification and development of an internationally reliable metric. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 669–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N.F.; Reilly, M.D.; Carsrud, A.L. Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voda, A.I.; Florea, N. Impact of Personality Traits and Entrepreneurship Education on Entrepreneurial Intentions of Business and Engineering Students. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapero, A. The entrepreneurial event. In The Environment for Entrepreneurship; Kent, C.A., Ed.; Lexington Books: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1984; pp. 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Wach, K.; Wojciechowski, L. Entrepreneurial Intentions of Students in Poland in the View of Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behaviour. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2016, 4, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugini, M.; Bagozzi, R.P. The role of desires and anticipated emotions in goal-directed behaviours: Broadening and deepening the theory of planned behaviour. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlaegel, C.; Koenig, M. Determinants of entrepreneurial intent: A meta-analytic test and integration of competing models. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 291–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Wu, L. The impact of higher education on entrepreneurial intentions of university students in China. J. Small Bus. Entrep. Dev 2008, 15, 752–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, F.; Marlino, D.; Kickul, J. Our entrepreneurial future: Examining the diverse attitudes and motivations of teens across gender and ethnic identity. J. Dev. Entrep. 2004, 9, 177–197. [Google Scholar]

- Souitaris, V.; Zerbinati, S.; Al-Laham, A. Do entrepreneurship programmes raise entrepreneurial intention of science and engineering students? The effect of learning, inspiration and resources. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 566–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajeddini, K.; Mueller, S.L. Corporate Entrepreneurship in Switzerland: Evidence from a Case Study of Swiss Watch Manufacturers. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2012, 8, 355–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, D. Innovation and Entrepreneurship: Practices and Principles; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1985; pp. 150–152. [Google Scholar]

- Verheul, I.; Wennekers, S.; Audretsch, D.; Thurik, R. An Eclectic Theory of Entrepreneurship: Policies, Institutions and Culture; Audretsch, D., Thurik, R., Verheul, I., Wennekers, S., Eds.; Entrepreneurship: Determinants and Policy in a European-US Comparison; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 11–81. [Google Scholar]

- Carcamo-Solis, M.D.L.; Arroyo-Lopez, M.D.P.; Alvarez-Castanon, L.D.C.; Garcia-Lopez, E. Developing entrepreneurship in primary schools. The Mexican experience of “My first enterprise: Entrepreneurship by playing”. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 64, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayolle, A.; Gailly, B.; Lassas-Clerc, N. Assessing the impact of entrepreneurship education programmes: A new methodology. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 2006, 30, 701–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crant, J.M. The proactive personality scale as a predictor of entrepreneurial intentions. J. Small Bus. Manag. 1996, 34, 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Franke, N.; Luthje, C. Entrepreneurial intentions of business students: A benchmark study. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Manag. 2004, 1, 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihie, Z.A.L.; Bagheri, A. Developing future entrepreneurs: A need to improve science students’ entrepreneurial participation. Int. J. Knowl. Cult. Chang. Manag. 2009, 9, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, G.; Liñán, F.; Fayolle, A.; Krueger, N.; Walmsley, A. The impact of entrepreneurship education in higher education: A systematic review and research agenda. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2017, 16, 277–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, Y.L.; Matlay, H. Entrepreneurship education in China. Educ. Train. 2003, 45, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhou, M.; Xu, H. A Review of Entrepreneurship Education for College Students in China. Adm. Sci. 2012, 2, 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Ministry of Education. The Ministry of Education’s Guidelines on Promoting Innovation and Entrepreneurship Education and Encouraging College Students to Start Up Their Business; Ministry of Education: Beijing, China, 2010. (In Chinese)

- Jose, C.S. Entrepreneurship Education in China. Entrepreneurship: Education and Training. Available online: https://www.intechopen.com/books/entrepreneurship-education-and-training/entrepreneurship-education-in-china (accessed on 25 March 2015).

- Millman, C.; Matlay, H.; Liu, F. Entrepreneurship education in China: A case study approach. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2008, 15, 802–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Duysters, G.; Cloodt, M. The role of entrepreneurship education as a predictor of university students’ entrepreneurial intention. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2013, 10, 623–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bernhofer, L.; Han, Z. Contextual factors and their effects on future entrepreneurs in China: A comparative study of entrepreneurial intentions. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2014, 65, 125–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, N.; Thomas, B. Challenges in University Technology Transfer and the Promising Role of Entrepreneurship Education. In The Chicago Handbook of University Technology Transfer and Academic Entrepreneurship; Albert, N.L., Donald, S.S., Mike, W., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2015; pp. 138–167. [Google Scholar]

- Brown., S.R. Q methodology and qualitative research. Qual. Health Res. 1996, 69, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, B.F.; McKeown, T.D. Q Methodology, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013; pp. 23–24. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, W. The Study of Behavior; Chicago University Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, S.; Stenner, P. Doing Q Methodological Research: Theory, Method & Interpretation; Sage Publications: London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; New Delhi, India; Singapore, 2012; pp. 7–8. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, R.M. Economic rationality and health and lifestyle choices for people with diabetes. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 63, 2341–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.R.; Durning, D.W.; Selden, S.C. Q methodology. In Handbook of Research Methods in Public Administration; Miller, G.R., Whicker, M.L., Eds.; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 599–637. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.R. Political Subjectivity: Applications of Q Methodology in Political Science; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1980; p. 355. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.R. A primer on Q methodology operant subjectivity. Operant Subj. 1993, 16, 91–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayett-Moreno, Y.; Villarraga-Flórez, L.F.; Rodríguez-Piñeros, S. Young Farmers’ Perceptions about Forest Management for Ecotourism as an Alternative for Development, in Puebla, Mexico. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webler, T.; Danielson, S.; Tuler, S. Using Q Method to Reveal Social Perspectives in Environmental Research; Social and Environmental Research Institute: Greenfield, MA, USA. Available online: www.seri- us.org/pubs/Qprimer.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2009).

- Stephenson, W. Correlating persons instead of tests. J. Personal. 1935, 4, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmolck, P. PQMethod Manual. Available online: http://schmolck.org/qmethod/pqmanual.htm. (accessed on 26 March 2014).

- Esfandiar, K.; Sharifi-Tehrani, M.; Pratt, S.; Altinay, L. Understanding entrepreneurial intentions: A developed integrated structural model approach. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 94, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espíritu-Olmos, R.; Sastre-Castillo, M.A. Personality traits versus work values: Comparing psychological theories on entrepreneurial intention. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1595–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, A. Creating conducive environments for learning and entrepreneurship: Living with, dealing with, creating and enjoying uncertainty and complexity. Ind. High. Educ. 2002, 16, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, C.G.; Sung, C.; Park, J.; Choi, D.A. Study on the Effectiveness of Entrepreneurship Education Programs in Higher Education Institutions: A Case Study of Korean Graduate Programs. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2018, 4, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shook, C.L.; Bratianu, C. Entrepreneurial intent in a transitional economy: An application of the theory of planned behavior to Romanian students. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2010, 6, 231–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, H.; Lautenschlager, A. The ‘teachability dilemma’ of entrepreneurship. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2011, 7, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, S.L.; Thomas, A.S. Culture and entrepreneurial potential: Culture and entrepreneurial potential: A nine country study of locus of control and innovativeness. J. Bus. Ventur. 2001, 16, 51–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieckmann, M. Future-oriented higher education: Which key competencies should be fostered through university teaching and learning? Futures 2012, 44, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minola, T.; Criaco, G.; Obschonka, M. Age, culture, and self-employment motivation. Small Bus. Econ. 2016, 46, 187–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobl, A.; Kronenberg, C.; Peters, M. Entrepreneurial attitudes and intentions: Assessing gender specific differences. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2012, 15, 452–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzarol, T.; Volery, T.; Doss, N.; Thein, V. Factors influencing small business start-ups. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 1999, 5, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.; Akhtar, F.; Das, N. Entrepreneurial intention among science & technology students in India: Extending the theory of planned behavior. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2017, 13, 1013–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Most Disagree | Neutral | Most Agree | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −4 | −3 | −2 | −1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| ID | Factor A | Factor B | Factor C |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 60 | ||

| 5 | 42 | ||

| 7 | 46 | ||

| 13 | 50 | ||

| 20 | 62 | ||

| 24 | 70 | ||

| 25 | 52 | ||

| 26 | 69 | ||

| 28 | 79 | ||

| 3 | 61 | ||

| 6 | 52 | ||

| 8 | 66 | ||

| 14 | 78 | ||

| 15 | 51 | ||

| 16 | 64 | ||

| 18 | 72 | ||

| 19 | 45 | ||

| 27 | 55 | ||

| 1 | 41 | ||

| 9 | 75 | ||

| 10 | 72 | ||

| 11 | 49 | ||

| 12 | 67 | ||

| 23 | 60 | ||

| 29 | 47 | ||

| 30 | 44 |

| Factor A: Intellectual Entrepreneur | ||

| No. | Q Statement | Score |

| 25 | The ability to rebuild self-confidence after a setback. | +4 |

| 2 | The one who has strong interests in staring a business will have strong entrepreneurial intention. | +3 |

| 27 | Business opportunity and market timing are important. | +3 |

| 17 | The government’s supportive policies such as venture capital will make students think of starting a business. | +3 |

| 6 | The accumulation of a person’s social capital would affect his entrepreneurial intention, such as interpersonal relationship, opportunities, resources, markets. | +2 |

| 16 | Technological entrepreneurship requires the support of technology. Once technology is available, the intention will be stronger. | +1 |

| 14 | Participating in entrepreneurship education and training course provided by the school will increase my entrepreneurial intent. | 0 |

| 19 | The propaganda of a large amount of entrepreneurial information made us want to have a try. | −3 |

| 4 | Participating in the school’s entrepreneurial competition will has an impact on one’s entrepreneurial intention. | −3 |

| 31 | If you can’t find a job after graduation, you may want to start a business when you are under employment pressure. | −3 |

| 5 | Gender will affect entrepreneurial attitudes. | −4 |

| Factor B: Opportunity Driven Entrepreneur | ||

| No. | Q Statement | Score |

| 22 | If you find a suitable entrepreneurial project or accurate business direction, it will affect your intention. | +4 |

| 21 | Your partner and your future team member are important. | +3 |

| 20 | Money is an important factor. | +3 |

| 6 | The accumulation of a person’s social capital would affect his entrepreneurial intention, such as interpersonal relationship, opportunities, resources, markets. | +3 |

| 16 | Technological entrepreneurship requires the support of technology. Once technology is available, the intention will be stronger. | +2 |

| 14 | Participating in an entrepreneurship education and training course provided by the school will increase my intent. | −3 |

| 31 | If you can’t find a job after graduation, you may want to start a business when you are under employment pressure. | −3 |

| 9 | Different age groups have different entrepreneurial intentions. | −3 |

| 18 | The government provides entrepreneurial skills training in college, such as SYB * courses, which will enhance my entrepreneurial intentions. | −4 |

| (*) SYB’s full name is “START YOUR BUSINESS”, which means “Start Your Business”. It is an important part of the "Starting and Improving Your Business" (SIYB) series of training courses, which provides training for those who want to start their own small and medium enterprises. | ||

| Factor C: Individualistic Entrepreneur | ||

| No. | Q Statement | Score |

| 2 | The one who has strong interest in staring a business will have strong entrepreneurial intention. | +4 |

| 3 | Different educational backgrounds and the intentions of starting a business will be different. | +3 |

| 8 | An individual must have the ability to start a business. | +3 |

| 6 | The accumulation of a person’s social capital would affect his entrepreneurial intention, such as interpersonal relationship, opportunities, resources, markets. | +3 |

| 16 | Technological entrepreneurship requires the support of technology. Once technology is available, the intention will be stronger. | +2 |

| 9 | Different ages have different entrepreneurial intentions. | −3 |

| 19 | The propaganda of a large amount of entrepreneurial information made us want to have a try. | −3 |

| 29 | Part-time job experience will influence entrepreneurial ideas. | −3 |

| 31 | If you can’t find a job after graduation, you may want to start a business when you are under employment pressure. | −4 |

| Consensus statements | Factors | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Q Statements | A | B | C |

| 6 * | The accumulation of a person’s social capital would affect his entrepreneurial intention, such as interpersonal relationship, opportunities, resources, markets. | +2 | +3 | +3 |

| 13 | Leadership skills will affect the entrepreneurial intention. | +1 | +2 | 0 |

| 15 * | The entrepreneurial environment of college spurs me to start a business. | −2 | −2 | −1 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fang, C.; Chen, L. Exploring the Entrepreneurial Intentions of Science and Engineering Students in China: A Q Methodology Study. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2751. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102751

Fang C, Chen L. Exploring the Entrepreneurial Intentions of Science and Engineering Students in China: A Q Methodology Study. Sustainability. 2019; 11(10):2751. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102751

Chicago/Turabian StyleFang, Chen, and Liwen Chen. 2019. "Exploring the Entrepreneurial Intentions of Science and Engineering Students in China: A Q Methodology Study" Sustainability 11, no. 10: 2751. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102751

APA StyleFang, C., & Chen, L. (2019). Exploring the Entrepreneurial Intentions of Science and Engineering Students in China: A Q Methodology Study. Sustainability, 11(10), 2751. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102751