The Resilience Capabilities of Yumcha Restaurants in Shaping the Sustainability of Yumcha Culture

Abstract

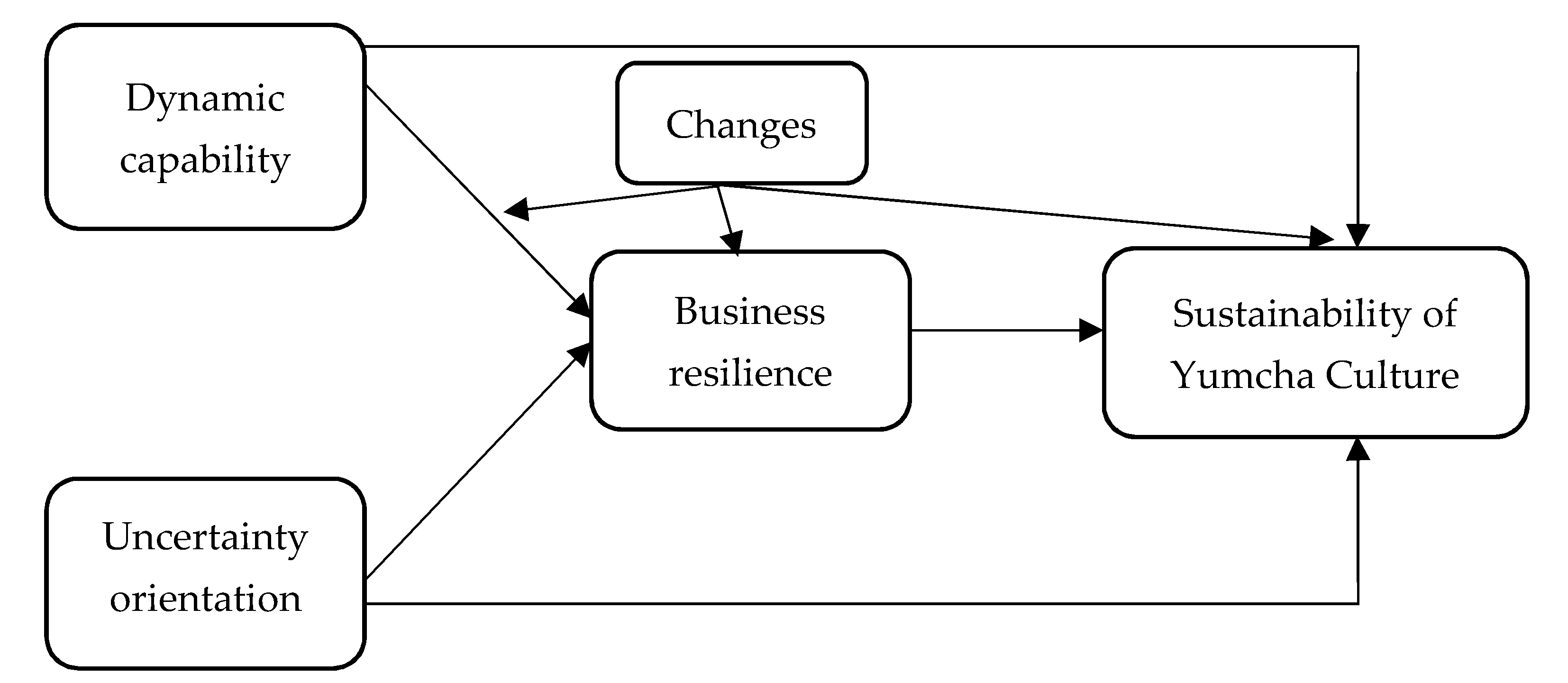

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Restaurant Resilience and Local Food-Heritage Sustainability

2.2. Dynamic Capability

2.2.1. Uncertainty Orientation

2.2.2. Proactive Behavior

2.3. Impact of Globalization

3. Methods

3.1. Sample, Data Collection, and Research Context

3.2. Measures

3.3. Measure Assessment

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

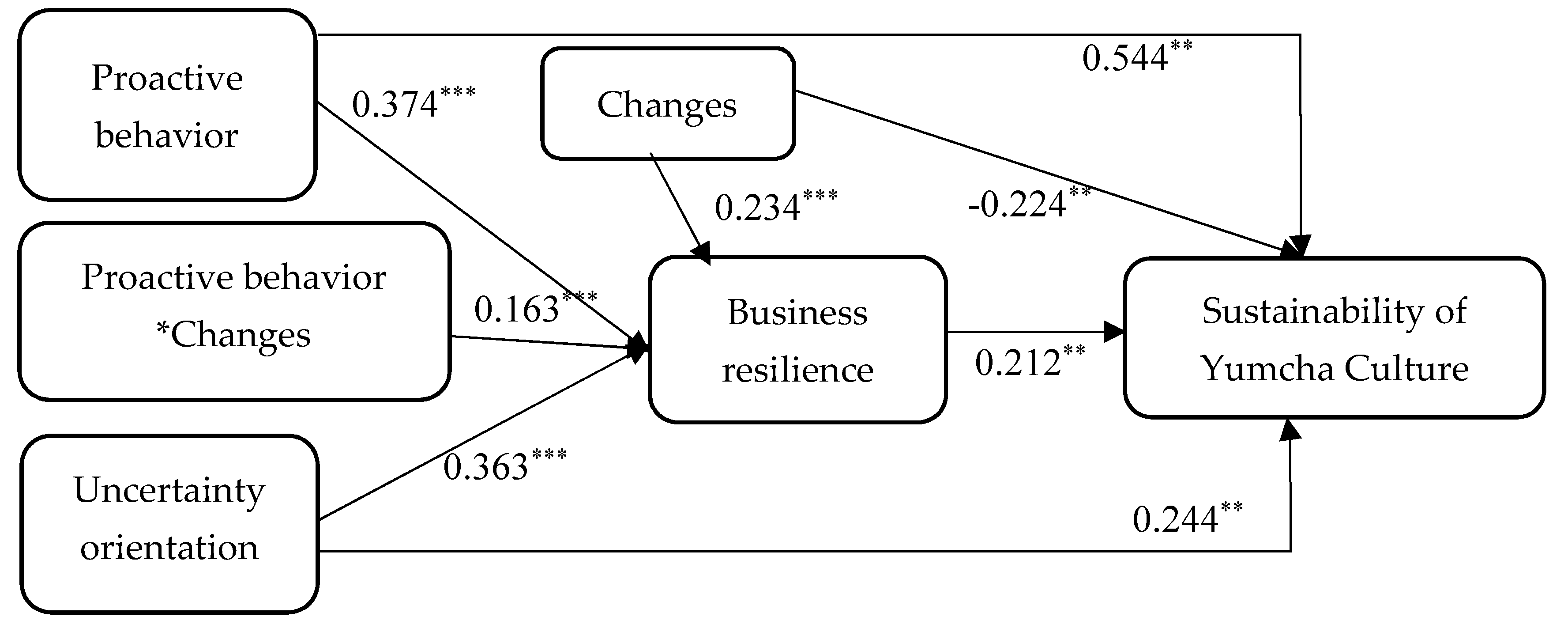

4.2. Hypothesis Test

4.3. Model Comparison

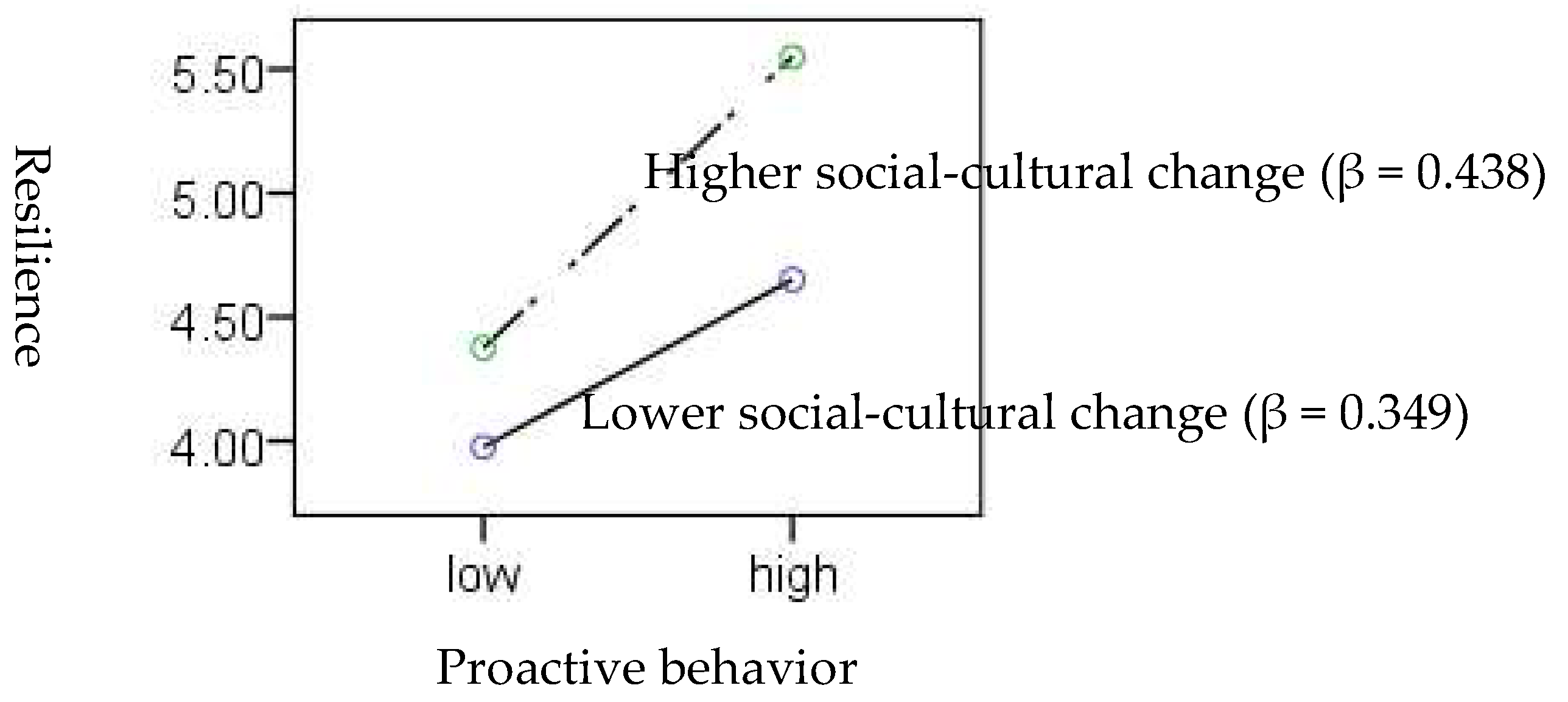

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Robertson, R. Globalization: Social Theory and Global Culture; Sage: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. The Condition of Postmodernity; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, S.K.; Tan, S.H.; Kok, Y.S.; Choon, S.W. Sense of place and sustainability of intangible cultural heritage–The case of George Town and Melaka. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 376–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.M. Culinary tourism: A folkloristic perspective on eating and otherness. South. Folklore 1998, 55, 181. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, J.C. Food as a tourism resource: A view from Singapore. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2004, 29, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Beltrán, F.J.; López-Guzmán, T.; González Santa Cruz, F. Analysis of the relationship between tourism and food culture. Sustainability 2016, 8, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadway, M.J. ‘Putting place on a plate’ along the West Cork Food Trail. Tour. Geogr. 2017, 19, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrovski, D.; Vallbona, M.C. Urban food markets in the context of a tourist attraction—La Boqueria market in Barcelona, Spain. Tour. Geogr. 2018, 20, 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, S.M. Heunggongyan forever: Immigrant life and Hong Kong style Yumcha in Australia. In The Globalization of Chinese Food; Wu, D.Y.H., Cheung, S.C.H., Eds.; University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2002; pp. 131–151. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L. Tea and Dim Sum: Cantonese Style Morning Tea; Guangdong Education Press: Guangzhou, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Song, S. The impacts of Guangdong Zaocha culture on table manners and modern lifestyles. Mod. Commun. 2018, 6, 103–105. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson, M.; Milestad, R.; Hahn, T.; Von Oelreich, J. The resilience of a sustainability entrepreneur in the Swedish food system. Sustainability 2016, 8, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Tang, L.R.; Bosselman, R. Measuring customer perceptions of restaurant innovativeness: Developing and validating a scale. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 74, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, S. Sustainable development mechanism of food culture’s translocal production based on authenticity. Sustainability 2014, 6, 7030–7047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prideaux, B. Commodifying Heritage: Loss of Authenticity and Meaning or an Appropriate Response to Difficult Circumstances? Int. J. Tour. Sci. 2003, 3, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, J.; Lin, M. Study on control of tourism commercialization in historic town and village. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2014, 69, 268–277. [Google Scholar]

- Su, J. Understanding the changing Intangible Cultural Heritage in tourism commodification: The music players’ perspective from Lijiang, China. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, H.; Ameen, K. The role of resilience capabilities in shaping how firms respond to disruptions. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 88, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WCED. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987; p. 43. [Google Scholar]

- Throsby, D. Sustainability and culture some theoretical issues. Int. J. Cult. Policy 1997, 4, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coben, L.S. Sustainability and Cultural Heritage. In Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology; Smith, C., Ed.; Springer Reference: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 7155–7157. [Google Scholar]

- Daskon, C.D. Cultural resilience—the roles of cultural traditions in sustaining rural livelihoods: A case study from rural Kandyan villages in Central Sri Lanka. Sustainability 2010, 2, 1080–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.R.; Zhang, J. Research progress and themes of geography on community resilience. Prog. Geogr. 2015, 34, 100–109. [Google Scholar]

- Lew, A.A. Scale, change and resilience in community tourism planning. Tour. Geogr. 2014, 16, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roundy, P.T.; Brockman, B.K.; Bradshaw, M. The resilience of entrepreneurial ecosystems. J. Bus. Ventur. Insight 2017, 8, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Vegt, G.S.; Essens, P.; Wahlström, M.; George, G. Managing risk and resilience. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 58, 971–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfat, C.E.; Winter, S.G. Untangling dynamic and operational capabilities: Strategy for the (N)ever-changing world. Strateg. Manag. J. 2011, 32, 1243–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, S.G. Understanding dynamic capabilities. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 991–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantunen, A.; Puumalainen, K.; Saarenketo, S.; Kyläheiko, K. Entrepreneurial orientation, dynamic capabilities and international performance. J. Int. Entrep. 2005, 3, 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Krapfel, R.; LaBahn, D. Product innovativeness and entry strategy: Impact on cycle time and break-even time. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 1995, 12, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, R.; Calantone, R. A critical look at technological innovation typology and innovativeness terminology: A literature review. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2002, 19, 110–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubera, G.; Ordanini, A.; Griffith, D.A. Incorporating cultural values for understanding the influence of perceived product creativity on intention to buy: An examination in Italy and the US. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2011, 42, 459–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feltenstein, A. An intertemporal general equilibrium analysis of financial crowding out: A policy model and an application to Australia. J. Public. Econ. 1986, 31, 79–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, L.L.; Shankar, V.; Parish, J.T.; Cadwallader, S.; Dotzel, T. Creating new markets through service innovation. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2006, 47, 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, R.D.; Sandler, M. The use of technology to improve service quality: A look at the extent of service improvements to be gained through investments in technology and expanded facilities and programs. Cornell Hosp. Q. 1992, 33, 68–73. [Google Scholar]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. The new frontier of experience innovation. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2003, 44, 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sashi, C.M. Customer engagement, buyer-seller relationships, and social media. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipe, L.J. How do senior managers influence experience innovation? Insights from a hospitality marketplace. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 54, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jernsand, E.M.; Kraff, H.; Mossberg, L. Tourism experience innovation through design. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2015, 15, 98–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, D.; Ailawadi, K.L.; Gauri, D.; Hall, K.; Kopalle, P.; Robertson, J.R. Innovations in retail pricing and promotions. J. Retail. 2011, 87, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, N.F.; Ellis-Chadwick, F. Internet retailing: The past, the present and the future. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2010, 38, 943–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, V.; Inman, J.J.; Mantrala, M.; Kelley, E.; Rizley, R. Innovations in shopper marketing: Current insights and future research issues. J. Retail. 2011, 87, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.Y.; Marshall, D.; Dawson, J. How does perceived convenience retailer innovativeness create value for the customer? Int. J. Bus. Econ. 2013, 12, 171–179. [Google Scholar]

- Bode, C.; Wagner, S.M.; Petersen, K.J.; Ellram, L.M. Understanding responses to supply chain disruptions: Insights from information processing and resource dependence perspectives. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 833–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaytán, M.S. Globalizing resistance: Slow Food and new local imaginaries. Food Cult. Soc. 2004, 7, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, R. Homogenization. In Globalization: The Key Concepts; Mooney, A., Evans, B., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; pp. 123–124. [Google Scholar]

- Ritzer, G.; Ryan, M. The globalization of nothing. Soc. Thought Res. 2002, 25, 51–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, H. Social Acceleration: A New Theory of Modernity; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fainshmidt, S.; Pezeshkan, A.; Lance Frazier, M.; Nair, A.; Markowski, E. Dynamic capabilities and organizational performance: A meta-analytic evaluation and extension. J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 53, 1348–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantunen, A.; Tarkiainen, A.; Chari, S.; Oghazi, P. Dynamic capabilities, operational changes, and performance outcomes in the media industry. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 89, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zikmund, W.G.; Babin, B.J.; Carr, J.C.; Griffin, M. Business Research Methods, 9th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill, G.A., Jr. A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambulkar, S.; Blackhurst, J.; Grawe, S. Firm’s resilience to supply chain disruptions: Scale development and empirical examination. J. Oper. Manag. 2015, 33, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B. Mplus User’s Guide; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. Multitrait-multimethod matrices in consumer research. J. Consum. Res. 1991, 17, 426–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Lyu, Y.; Deng, X.; et al. Workplace ostracism and proactive customer service performance: A conservation of resources perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 64, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Hult, G.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM); Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with EQS and EQS/Windows: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Seibert, S.E.; Kraimer, M.L.; Liden, R.C. A social capital theory of career success. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 219–237. [Google Scholar]

- Cortina, J.M.; Chen, G.; Dunlap, W.P. Testing interaction effects in LISREL: Examination and illustration of available procedures. Organ. Res. Methods 2001, 4, 324–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saris, W.E.; Batista-Foguet, J.M.; Coenders, G. Selection of indicators for the Interaction term in structural equation models with interaction. Qual. Quant. 2007, 41, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M.; Bonnet, D.C. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, J.R.; Lambert, L.S. Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytic framework using moderated path analysis. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, S.; Xiao, H.; Zhou, L. Commodification and perceived authenticity in commercial homes. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 71, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Xu, H. A system dynamics approach to explore sustainable policies for Xidi, the world heritage village. Curr. Issues Tour. 2012, 15, 441–459. [Google Scholar]

- Chrzan, J. Slow food: What, why, and to where? Food Cult. Soc. 2004, 7, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonetti, L. The ideology of slow food. J. Eur. Stud. 2012, 42, 168–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Factor | M | SD | Skew | Kurt | EFL | CFL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product innovativeness (Cronbach’s α: 0.897, CR: 0.897; AVE: 0.702) | 18.6% a | ||||||

| At1 | Yumcha restaurants offer new flavors. | 5.41 | 1.417 | –0.654 | –0.024 | 0.750 | 0.794 |

| At2 | Yumcha restaurants offer new combinations of food. | 5.31 | 1.450 | –0.722 | 0.227 | 0.807 | 0.869 |

| At3 | Yumcha restaurants offer innovative presentation of food. | 5.34 | 1.391 | –0.595 | 0.032 | 0.747 | 0.849 |

| At4 | Yumcha restaurants introduce new menu items. | 5.59 | 1.431 | –0.761 | –0.059 | 0.766 | 0.8 |

| Service innovativeness (Cronbach’s α: 0.853, CR: 0.857; AVE: 0.667) | 14.9% a | ||||||

| As1 | Yumcha restaurants’ procedure for ordering menu items is innovative. | 5.58 | 1.412 | –0.783 | 0.223 | 0.860 | 0.835 |

| As2 | Yumcha restaurants integrate innovative technologies in new processes for offering their services. | 5.20 | 1.359 | –0.371 | −0.190 | 0.651 | 0.762 |

| As3 | Yumcha restaurants’ apps or online ordering tools make Yumcha restaurants make it easier for customers to order one-of-a-kind menu items compared to its competitors | 5.42 | 1.474 | –0.728 | 0.144 | 0.815 | 0.851 |

| Experiential innovations (Cronbach’s α: 0.929, CR: 0.93; AVE: 0.72) | 20.0% a | ||||||

| Ae1 | Yumcha restaurants offer unique characteristic features that set it apart from its competitors. | 5.30 | 1.371 | –0.616 | 0.152 | 0.921 | 0.823 |

| Ae2 | Traditional culture is integrated into Yumcha restaurants | 5.65 | 1.375 | –0.792 | 0.144 | 0.779 | 0.812 |

| Ae3 | The characteristics of Yumcha restaurants provide an innovative environment that makes them unique. | 5.37 | 1.428 | –0.642 | 0.022 | 0.763 | 0.896 |

| Ae4 | The characteristics of Yumcha restaurants provide an innovative design that differentiates them from their competitors. | 5.23 | 1.361 | –0.406 | –0.230 | 0.680 | 0.85 |

| Ae5 | Yumcha restaurants are well-known for innovative custom events. | 5.42 | 1.383 | −0.590 | –0.134 | 0.790 | 0.873 |

| Promotional innovativeness (Cronbach’s α: 0.919, CR: 0.92; AVE: 0.70) | 21.9% a | ||||||

| Ap1 | Yumcha restaurants are always thinking of ways to expand and offer new benefits to its customers in order to give them a better experience. | 5.12 | 1.397 | –0.397 | –0.326 | 0.713 | 0.837 |

| Ap2 | The way Yumcha restaurant employees interact with their customers is innovative. | 5.09 | 1.394 | –0.431 | 0.004 | 0.782 | 0.803 |

| Ap3 | Yumcha restaurants have an innovative rewards (membership) program. | 5.11 | 1.394 | –0.469 | 0.200 | 0.921 | 0.86 |

| Ap4 | Yumcha restaurants implement new advertising strategies not currently used by their competitors. | 5.25 | 1.368 | –0.376 | –0.262 | 0.766 | 0.843 |

| Ap5 | Yumcha restaurants adopt novel ways to market themselves to customers. | 5.08 | 1.349 | –0.275 | –0.168 | 0.733 | 0.817 |

| Cumulative validity | 75.4% a | ||||||

| Factor | Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | C Factor Loading | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proactive behavior (Cronbach’s α: 0.880, composite reliability (CR): 0.89; average variance extracted (AVE): 0.67) | ||||||

| P1 | Product innovativeness | 5.41 | 1.243 | –0.789 | 0.641 | 0.780 |

| P2 | Service innovativeness | 5.40 | 1.245 | –0.644 | 0.449 | 0.755 |

| P3 | Experiential innovativeness | 5.39 | 1.221 | –0.619 | 0.336 | 0.883 |

| P4 | Promotional innovation | 5.13 | 1.201 | –0.341 | 0.281 | 0.85 |

| Uncertainty orientation of demand change (Cronbach’s α: 0.880, CR: 0.88; AVE: 0.65) | ||||||

| U1 | Various social changes have highlighted the fragility of Yumcha restaurants and demonstrated improvements to Yumcha restaurants. | 4.96 | 1.286 | –0.151 | –0.057 | 0.719 |

| U2 | Yumcha restaurants recognize the impact of social change at any time. | 5.04 | 1.251 | –0.106 | –0.201 | 0.819 |

| U3 | Yumcha restaurants have done a lot to better cope with social changes. | 5.15 | 1.243 | –0.095 | –0.299 | 0.827 |

| U4 | The impact on Yumcha restaurants is constantly reviewed. | 5.17 | 1.272 | –0.306 | –0.168 | 0.859 |

| Social–cultural changes (Cronbach’s α: 0.859, CR: 0.86; AVE: 0.62) | ||||||

| Im1 | Social change affects the Yumcha restaurant industry | 4.82 | 1.526 | –0.490 | –0.047 | 0.600 |

| Im2 | Customer tastes change increasingly faster, affecting the morning-tea industry. | 4.64 | 1.589 | –0.409 | –0.116 | 0.842 |

| Im3 | The way of life is getting increasingly faster in the Yumcha restaurant industry | 4.54 | 1.545 | –0.356 | –0.123 | 0.881 |

| Im4 | All kinds of catering enterprises continue to increase, affecting the morning-tea industry. | 4.50 | 1.574 | –0.448 | –0.059 | 0.803 |

| Yumcha heritage resilience (Cronbach’s α: 0.898, CR: 0.90; AVE: 0.69) | ||||||

| R1 | Yumcha culture can adapt to the impact of various shocks. | 4.84 | 1.285 | –0.077 | –0.110 | 0.832 |

| R2 | Yumcha restaurants can respond quickly to the impact of various shocks. | 4.73 | 1.298 | 0.002 | –0.087 | 0.854 |

| R3 | Yumcha restaurants have enough capacity to adapt to all kinds of impact. | 4.80 | 1.388 | –0.339 | 0.193 | 0.818 |

| R4 | Yumcha restaurants can quickly adjust business operations to cope with all kinds of impact. | 4.83 | 1.304 | –0.131 | 0.091 | 0.814 |

| Sustainability of Yumcha culture (Cronbach’s α: 0.901, CR: 0.91; AVE: 0.76) | ||||||

| Fu1 | I am full of confidence in the Yumcha restaurant industry | 5.38 | 1.386 | –0.629 | –0.007 | 0.915 |

| Fu2 | I think the Yumcha restaurant industry has a good future | 5.36 | 1.373 | –0.601 | 0.112 | 0.903 |

| Fu3 | I’d be happy to work in the Yumcha restaurant industry | 5.33 | 1.499 | –0.644 | –0.194 | 0.795 |

| χ2 | Df | RMSEA | SRMR | CFI | TLI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Five-factor model | 193.491 | 125 | 0.047 | 0.037 | 0.967 | 0.960 |

| 2 | Four-factor model: dynamic capability and uncertainty orientation were combined into one factor. | 301.339 | 129 | 0.073 | 0.051 | 0.918 | 0.903 |

| 3 | Three-factor model: Dynamic capability, uncertainty orientation, and impact were combined into one factor | 527.936 | 132 | 0.110 | 0.091 | 0.811 | 0.781 |

| 4 | Two-factor model: dynamic capability, uncertainty orientation, impact, and business resilience were combined into one factor | 625.729 | 134 | 0.122 | 0.094 | 0.766 | 0.732 |

| 5 | All variables were combined into one factor | 757.691 | 135 | 0.136 | 0.102 | 0.703 | 0.664 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Proactive behavior | 1 | |||

| 2 | Uncertainty orientation | 0.766 | 1 | ||

| 3 | Social–culture changes | 0.397 | 0.502 | 1 | |

| 4 | Yumcha restaurant resilience | 0.712 | 0.746 | 0.599 | 1 |

| 5 | Yumcha culture sustainability | 0.793 | 0.707 | 0.24 | 0.645 |

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M6 | M7 | M8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R->S | 0.212 ** | 0.215 * | 0.706 *** | 0.208 * | 0.294 *** | 0.235 ** | 0.690 ** | 0.198 ** |

| behavior->R | 0.374 *** | 0.361 *** | 0.396 *** | 0.331 ** | 0.358 *** | 0.413 *** | 0.422 *** | |

| Orientation->R | 0.363 *** | 0.359 *** | 0.473 *** | 0.344 ** | 0.378 *** | 0.420 *** | 0.377 *** | |

| Chang->R | 0.234 *** | 0.248 *** | 0.295 *** | 0.235 *** | 0.181 *** | 0.190 *** | ||

| Behavior * Change->R | 0.163 *** | 0.110 * | 0.162 *** | 0.076 *** | 0.156 *** | |||

| Behavior->S | 0.544 *** | 0.532 *** | 0.544 *** | 0.674 *** | 0.729 *** | 0.557 *** | ||

| Orientation->S | 0.244 *** | 0.247 ** | 0.249 ** | 0.347 *** | 0.253 *** | |||

| Change->S | –0.224 *** | –0.219 *** | −0.226 *** | −0.201 *** | −0.212 *** | −0.231 *** | ||

| Behavior * Change->S | 0.014 | 0.025 | ||||||

| χ2 | 397.521 | 287.555 | 325.586 | 404.171 | 397.298 | 493.051 | 397.298 | |

| Df | 175 | 86 | 157 | 176 | 174 | 178 | 174 | |

| Δχ2(ΔDf) | 110 (89) | –72 (18) | 6 (1) | –0.3 (1) | 104 (3) | –0.23 (1) | ||

| RMSEA | 0.072 | 0.097 | 0.066 | 0.072 | 0.072 | 0.084 | 0.072 | |

| SRMR | 0.045 | 0.076 | 0.049 | 0.047 | 0.045 | 0.045 | ||

| CFI | 0.943 | 0.929 | 0.949 | 0.942 | 0.943 | 0.920 | 0.943 | |

| TFI | 0.932 | 0.913 | 0.939 | 0.931 | 0.931 | 0.905 | 0.931 | |

| AIC | 15,065.95 | 12,165.86 | 9912.32 | 12,172.44 | 15,070.60 | 15,067.72 | 15,155.48 | 15,067.72 |

| ABIC | 15,085.18 | 12,188.53 | 9929.15 | 12,194.42 | 15,089.48 | 15,087.30 | 15,173.68 | 15,087.30 |

| Path | Class | Coefficient | Posterior S.D. | 95% Confidence Intervals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Higher | ||||

| behavior->R | Higher social–cultural changes | 1.019 | 0.092 | 0.837 | 1.194 |

| Lower social–cultural changes | 0.649 | 0.087 | 0.477 | 0.817 | |

| Difference in direct effect | 0.371 | 0.123 | 0.123 | 0.611 | |

| indirect effect | Higher social–cultural changes | 0.247 | 0.078 | 0.103 | 0.412 |

| Lower social–cultural changes | 0.155 | 0.052 | 0.063 | 0.268 | |

| Difference in indirect effect | 0.086 | 0.041 | 0.022 | 0.185 | |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dai, S.; Cui, Q.; Xu, H. The Resilience Capabilities of Yumcha Restaurants in Shaping the Sustainability of Yumcha Culture. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3304. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10093304

Dai S, Cui Q, Xu H. The Resilience Capabilities of Yumcha Restaurants in Shaping the Sustainability of Yumcha Culture. Sustainability. 2018; 10(9):3304. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10093304

Chicago/Turabian StyleDai, Shanshan, Qingming Cui, and Honggang Xu. 2018. "The Resilience Capabilities of Yumcha Restaurants in Shaping the Sustainability of Yumcha Culture" Sustainability 10, no. 9: 3304. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10093304

APA StyleDai, S., Cui, Q., & Xu, H. (2018). The Resilience Capabilities of Yumcha Restaurants in Shaping the Sustainability of Yumcha Culture. Sustainability, 10(9), 3304. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10093304