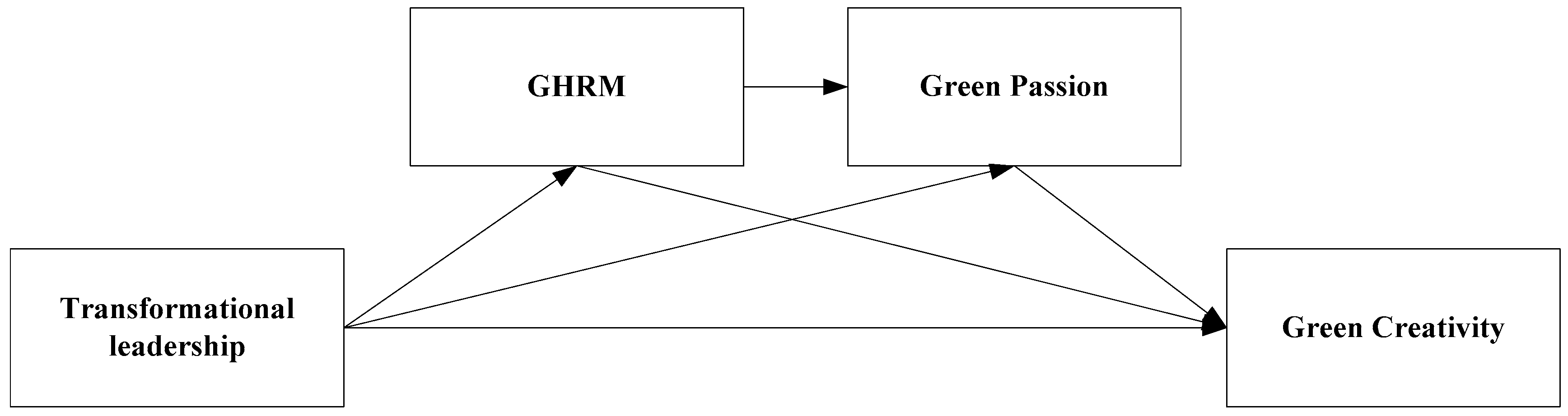

The Continuous Mediating Effects of GHRM on Employees’ Green Passion via Transformational Leadership and Green Creativity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Ability–Motivation–Opportunity Theory

2.2. Transformational Leadership and Employees’ Green Creativity

2.3. Transformational Leadership, GHRM, and Employees’ Green Creativity

2.4. Transformational Leadership and Employees’ Green Passion

2.5. Transformational Leadership, GHRM, and Employees’ Green Passion

2.6. Employees’ Green Passion and Green Creativity

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measures

4. Results

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

4.3. Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion and Conclusion

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Implications for Theories

5.3. Implications for Practices

5.4. Limitations and Future Directions

5.5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wyer, P.; Donohoe, S.; Matthews, P. Fostering strategic learning capability to enhance creativity in small service businesses. Serv. Bus. 2010, 4, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos-Nehles, A.; Renkema, M.; Janssen, M. HRM and innovative work behaviour: A systematic literature review. Pers. Rev. 2017, 46, 1228–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. The determinants of green product development performance: Green dynamic capabilities, green transformational leadership, and green creativity. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 116, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Yu, H. Green innovation strategy and green innovation: The roles of green creativity and green organizational identity. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, U.A. Linking justice, trust, and innovative work behaviour to work engagement. Pers. Rev. 2014, 43, 41–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, D.W.; Redman, T.; Maguire, S. Green human resource management: A review and research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Tang, G.; Jackson, S.E. Green human resource management research in emergence: A review and future directions. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2017, 2, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; Santos, F.C.A.; Nagano, M.S. Contributions of HRM throughout the stages of environmental management: Methodological triangulation applied to companies in Brazil. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2010, 21, 1049–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Huang, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, H.; Cai, Z. The effects of employee training on the relationship between environmental attitude and firms’ performance in sustainable development. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 2995–3008. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, G.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Paillé, P.; Jia, J. Green human resource management practices: Scale development and validity. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2018, 56, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelbaum, E.; Bailey, T.; Berg, P.; Kalleberg, A. Manufacturing Advantage: Why High-Performance Work Systems Pay Off; The Academy of Management Review; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Shalley, C.E. Deepening our understanding of creativity in the workplace: A review of different approaches to creativity research. In Zedeck Sheldon Apa Handbook of Industrial & Organizational Psychology; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; pp. 275–302. [Google Scholar]

- Hülsheger, U.R.; Anderson, N.; Salgado, J.F. Team-level predictors of innovation at work: A comprehensive meta-analysis spanning three decades of research. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 1128–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shalley, C.E.; Zhou, J.; Oldham, G.R. The effects of personal and contextual characteristics on creativity: Where should we go from here? J. Manag. 2004, 30, 933–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Cheung, S.Y.; Wang, M.; Huang, J.C. Unfolding the proactive process for creativity: Integration of the employee proactivity, information exchange, and psychological safety perspectives. J. Manag. 2012, 36, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, P.; Farmer, S.M. Creative self-efficacy development and creative performance over time. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.S.; Thompson, L. Membership Change in Groups: Implications for Group Creativity. In Creativity and Innovation in Organizational Teams; Thompson, L., Choi, H.S., Eds.; Psychology Press Ltd.: London, UK, 2006; pp. 87–108. [Google Scholar]

- Byron, K.; Khazanchi, S. A meta-analytic investigation of the relationship of state and trait anxiety to performance on figural and verbal creative tasks. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2012, 37, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H.; Yeh, S.L.; Cheng, H.I. Green shared vision and green creativity: The mediation roles of green mindfulness and green self-efficacy. Qual. Quant. 2015, 49, 1169–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E.; Taylor, S.; Muller-Camen, M. HR’s role in corporate social responsibility and sustainability. Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) Report, SHRM, Virginia. 2010. Available online: https://www.shrm.org/foundation/ourwork/initiatives/building-an-inclusive-culture/Documents/HR's%20Role%20in%20Corporate%20Social%20Responsibility.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2014).

- Zhu, Q.; Cordeiro, J.; Sarkis, J. Institutional pressures, dynamic capabilities and environmental management systems: Investigating the ISO 9000—Environmental management system implementation linkage. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 114, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gumusluoglu, L.; Ilsev, A. Transformational leadership, creativity, and organizational innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, S.; Dhar, R.L. Transformational leadership and employee creativity. Manag. Decis. 2015, 53, 894–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.Q.; Gardner, D.G.; Chen, H.G. Relationships between work team climate, individual motivation, and creativity. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 2094–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhart, B.; Fang, M. Pay, intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, performance, and creativity in the workplace: Revisiting long-held beliefs. Soc. Sci. Electron. Publ. 2015, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxall, P.; Purcell, J. Strategic Management and Human Resources: The Pursuit of Productivity, Flexibility and Legitimacy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, M.L.; Chiu, S.F.; Tan, R.R.; Siriban-Manalang, A.B. Sustainable consumption and production for Asia: Sustainability through green design and practice. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 40, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.Y.K. Does the natural-resource-based view of the firm apply in an emerging economy? A survey of foreign invested enterprises in china. J. Manag. Stud. 2005, 42, 625–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boselie, P.; Dietz, G.; Boon, C. Commonalities and contradictions in hrm and performance research. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2005, 15, 67–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colbert, B.A. The complex resource-based view: Implications for theory and practice in strategic human resource management. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2004, 29, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessey, B.A.; Amabile, T.M. Creativity. Soc. Sci. Electron. Publ. 2009, 61, 569–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuler, R.S.; Jackson, S.E. Organizational strategy and organization level as determinants of human resource management practices. Hum. Resour. Plan. 1987, 10, 125–141. [Google Scholar]

- Coff, R.; Kryscynski, D. Invited editorial: Drilling for micro-foundations of human capital-based competitive advantages. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1429–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delery, J.E.; Doty, D.H. Modes of theorizing in strategic human resource management: Tests of universalistic, contingency, and configurational performance predictions. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 802–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C.J.C. How green are HRM practices, organizational culture, learning and teamwork? A Brazilian study. Ind. Commer. Train. 2013, 43, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Kim, Y.; Han, K.; Jackson, S.E.; Ployhart, R.E. Multilevel influences on voluntary workplace green behavior: Individual differences, leader behavior, and coworker advocacy. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1335–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elrehailet, H.; Alsaad, A.; Alzghoul, A. The impact of transformational and authentic leadership on innovation in higher education: The contingent role of knowledge sharing. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Shang, Y.; Liu, H.; Xi, Y. Differentiated transformational leadership and knowledge sharing: A cross-level investigation. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Bartol, K.M.; Locke, E.A. Empowering leadership in management teams: Effects on knowledge sharing, efficacy, and performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 1239–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Bradley, J.; Liang, H. Team climate, empowering leadership, and knowledge sharing. J. Knowl. Manag. 2011, 15, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.J. The relationships between transformational leadership, knowledge sharing, trust and organizational citizenship behavior. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Manag. 2014, 5, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Waldman, D.A.; Yammarino, F.J. Leading in the 1990s: The four is of transformational leadership. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 1991, 15, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J. Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire: Manual Leader Form, Rater, and Scoring Key for Mlq (form 5x-short); Mind Garden, Inc.: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M.; Riggio, R.E. Transformational leadership. In Transformational Leadership, 2nd ed.; Psychology Press Ltd.: London, UK, 2006; p. 282. [Google Scholar]

- Özaralli, N. Effects of transformational leadership on empowerment and team effectiveness. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2003, 24, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnajdawi, S.; Emeagwali, O.L.; Elrehail, H. The Interplay among Green Human Resource Practices, Organization Citizenship Behavior for Environment and Sustainable Corporate Performance: Evidence from Jordan. J. Environ. Account. Manag. 2017, 5, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, D.I.; Chow, C. The role of transformational leadership in enhancing organizational innovation: Hypotheses and some preliminary findings. Leadersh. Q. 2003, 14, 525–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M. Leadership and Performance beyond Expectation; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, R.E.; Bate, J.D. The Power of Strategy Innovation: A New Way of Linking Creativity and Strategic Planning to Discover Great Business Opportunities; AMACOM Division, American Management Association: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Eiadat, Y.; Kelly, A.; Roche, F.; Eyadat, H. Green and competitive? An empirical test of the mediating role of environmental innovation strategy. J. World Bus. 2008, 43, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.K.; Sarkar, S.; Kiranmai, J. Green HRM: Innovative approach in indian public enterprises. World Rev. Sci. Technol. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 11, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrone, P.; Gomezmejia, L.R. Environmental performance and executive compensation: An integrated agency-institutional perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, K.B.; Nilan, K. Environmental sustainability and employee engagement at 3M. In Managing Human Resources for Environmental Sustainability; Jackson, S.E., Ones, D.S., Dilchert, S., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA; pp. 267–280.

- Yang, J.T. Knowledge sharing: Investigating appropriate leadership roles and collaborative culture. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 530–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, R.S.; Cordano, M.; Silverman, M. Exploring individual and institutional drivers of proactive environmentalism in the U.S. wine industry. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2005, 14, 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carton, A.M.; Murphy, C.; Clark, J.R. A (blurry) vision of the future: How leader rhetoric about ultimate goals influences performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 1544–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, K.; Foss, N.J. New human resource management practices, complementarities and the impact on innovation performance. Camb. J. Econ. 2003, 27, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messersmith, J.G.; Guthrie, J.P. High performance work systems in emergent organizations: Implications for firm performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2010, 49, 241–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumford, M.D. Managing creative people: Strategies and tactics for innovation. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2000, 10, 313–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipton, H.; West, M.A.; Dawson, J.; Birdi, K.; Patterson, M. HRM as a predictor of innovation. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2006, 16, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Lepak, D.P.; Han, K.; Hong, Y.; Kim, A.; Winkler, A. Clarifying the construct of human resource systems: Relating human resource management to employee performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2012, 22, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bysted, R.; Hansen, J. Comparing public and private sector employees’ innovative behavior. Public Manag. Rev. 2015, 17, 698–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, T. Harmony and organizational citizenship behavior in Chinese organizations. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 26, 1110–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gousse-Lessard, A.S.; Vallerand, R.J.; Carbonneau, N.; Lafreniere, M.A.K. The role of passion in mainstream and radical behaviors: A look at environmental activism. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 35, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.L.; Barling, J. Greening organizations through leaders’ influence on employees’ pro-environmental behaviors. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 176–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, P.; Cortez, P.; Santos, H. Automatic Human Action Recognition from Video Using Hidden Markov Model. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Science and Engineering, Porto, Portugal, 21–23 October 2016; pp. 105–109. [Google Scholar]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, N.J.; Cialdini, R.B.; Griskevicius, V. A room with a viewpoint: Using social norms to motivate environmental conservation in hotels. J. Consum. Res. 2008, 35, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bledow, R.; Rosing, K.; Frese, M. A dynamic perspective on affect and creativity. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 432–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.M.; Zhou, J. Dual tuning in a supportive context: Joint contributions of positive mood, negative mood, and supervisory behaviors to employee creativity. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 605–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, D.A.; Ramírez, G.G.; House, R.J.; Puranam, P. Does leadership matter? CEO leadership attributes and profitability under conditions of perceived environmental uncertainty. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 134–143. [Google Scholar]

- Brislin, R.W. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.C.; Dang, T.T.H.; Liu, Y.S. CEO transformational leadership and firm performance: A moderated mediation model of TMT trust climate and environmental dynamism. Asia Pacific J. Manag. 2016, 33, 981–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mccollkennedy, J.R.; Anderson, R.D. Impact of leadership style and emotions on subordinate performance. Leadersh. Q. 2002, 13, 545–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Hoever, I.J. Research on workplace creativity: A review and redirection. Soc. Sci. Electron. Publ. 2014, 1, 333–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, M. The strength-of-weak-ties perspective on creativity: A comprehensive examination and extension. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 592–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Bartol, K.M. Linking empowering leadership and employee creativity: The influence of psychological empowerment, intrinsic motivation, and creative process engagement. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T. A model of creativity and innovation in organizations. In Research in Organizational Behavior; Staw, B.M., Cummings, L.L., Eds.; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1988; Volume 10, pp. 123–167. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, S.E.; Renwick, D.W.; Jabbour, C.J.; Muller-Camen, M. State-of-the-art and future directions for green human resource management: Introduction to the special issue. Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 25, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.E.; Seo, J. The greening of strategic HRM scholarship. Organ. Manag. J. 2010, 7, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBois, C.L.; Dubois, D.A. Strategic HRM as social design for environmental sustainability in organization. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 51, 799–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, G.; Williams, K.; Probert, J. Greening the airline pilot: HRM and the green performance of airlines in the UK. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 152–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.Y.; Cai, Z.Y.; Liu, Z.Q.; Hong, Z.; Xin, Y.; Ji, L. The importance of ethical leadership in employees’ value congruence and turnover. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2015, 56, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messersmith, J.G.; Wales, W.J. Entrepreneurial orientation and performance in young firms: The role of human resource management. Int. Small Bus. J. 2013, 31, 115–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Categories | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | male | 77 | 64.17% |

| female | 43 | 35.83% | |

| Age a | under 25 | 9 | 7.50% |

| 26–30 | 34 | 28.33% | |

| 31–35 | 14 | 11.67% | |

| 36–40 | 36 | 30.50% | |

| 41–45 | 14 | 11.67% | |

| 46–50 | 13 | 10.33% |

| Model | χ2 | Df | RMSEA | TLI | CFI | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four-factor model | 200.20 | 129 | 0.07 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.05 |

| Three-factor model a | 345.13 | 132 | 0.12 | 0.84 | 0.87 | 0.07 |

| Three-factor model b | 366.63 | 132 | 0.12 | 0.83 | 0.85 | 0.08 |

| Two-factor model c | 539.79 | 134 | 0.16 | 0.71 | 0.74 | 0.10 |

| One-factor model | 827.43 | 135 | 0.21 | 0.50 | 0.56 | 0.14 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 1 | ||||||

| 2. Gender a | −0.35 ** | 1 | |||||

| 3. Tenure with the leader | 0.56 ** | −0.15 | 1 | ||||

| 4. Transformational leadership | 0.13 | −0.02 | 0.18 * | (0.89)b | |||

| 5. GHRM | −0.11 | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.47 ** | (0.91)c | ||

| 6. Green passion | −0.04 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.36 ** | 0.52 ** | (0.89)d | |

| 7. Green creativity | −0.05 | 0.25 ** | −0.04 | 0.31 ** | 0.57 ** | 0.56 ** | (0.76)e |

| Mean | 35.37 | 0.36 | 5.71 | 4.01 | 3.88 | 4.14 | 3.84 |

| SD | 7.26 | 0.48 | 4.93 | 0.58 | 0.50 | 0.56 | 0.58 |

| GHRM | Green Passion | Green Creativity | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 | Model 10 | |

| Controls | ||||||||||

| Age | −0.18 | −0.20 | −0.11 | −0.12 | −0.03 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.18 |

| Gender | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.31 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.22 * | 0.26 ** | 0.22 ** |

| Tenure with the leader | 0.23 * | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.04 | −0.02 | −0.08 | −0.16 | −0.14 | −0.17 * |

| Independent Variable | ||||||||||

| Transformational leadership | 0.46 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.15 | 0.32 ** | 0.07 | 0.14 | 0.01 | |||

| Mediators | ||||||||||

| GHRM | 0.43 ** | 0.53 ** | 0.37 ** | |||||||

| Green passion | 0.51 ** | 0.38 ** | ||||||||

| F | 2.76 * | 9.83 ** | 1.08 | 4.45 ** | 8.05 ** | 3.27 * | 5.78 ** | 12.99 ** | 14.11 ** | 16.28 ** |

| R2 | 0.08 | 0.28 | 0.03 | 0.15 | 0.29 | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.40 | 0.42 | 0.50 |

| ΔF | 2.76 * | 28.75 | 1.08 | 14.13 ** | 19.21 ** | 3.27 * | 12.21 ** | 34.16 ** | 38.70 ** | 20.16 ** |

| ΔR2 | 0.08 | 0.21 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.10 |

| Mechanism | Effect Amount | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | Transformational leadership → Green creativity | 0.31 | (0.169, 0.461) |

| Indirect effect | Transformational leadership → GHRM → Green passion → Green creativity | 0.08 | (0.043, 0.137) |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jia, J.; Liu, H.; Chin, T.; Hu, D. The Continuous Mediating Effects of GHRM on Employees’ Green Passion via Transformational Leadership and Green Creativity. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3237. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10093237

Jia J, Liu H, Chin T, Hu D. The Continuous Mediating Effects of GHRM on Employees’ Green Passion via Transformational Leadership and Green Creativity. Sustainability. 2018; 10(9):3237. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10093237

Chicago/Turabian StyleJia, Jianfeng, Huanxin Liu, Tachia Chin, and Dongqing Hu. 2018. "The Continuous Mediating Effects of GHRM on Employees’ Green Passion via Transformational Leadership and Green Creativity" Sustainability 10, no. 9: 3237. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10093237

APA StyleJia, J., Liu, H., Chin, T., & Hu, D. (2018). The Continuous Mediating Effects of GHRM on Employees’ Green Passion via Transformational Leadership and Green Creativity. Sustainability, 10(9), 3237. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10093237