Influence of Environmental Knowledge on Affect, Nature Affiliation and Pro-Environmental Behaviors among Tourists

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Background

2.2. Environmental Knowledge

2.3. Environmental Affect

2.4. Nature Affiliation and Pro-Environmental Behavior

2.5. Research Hypothesis Development

3. Methods

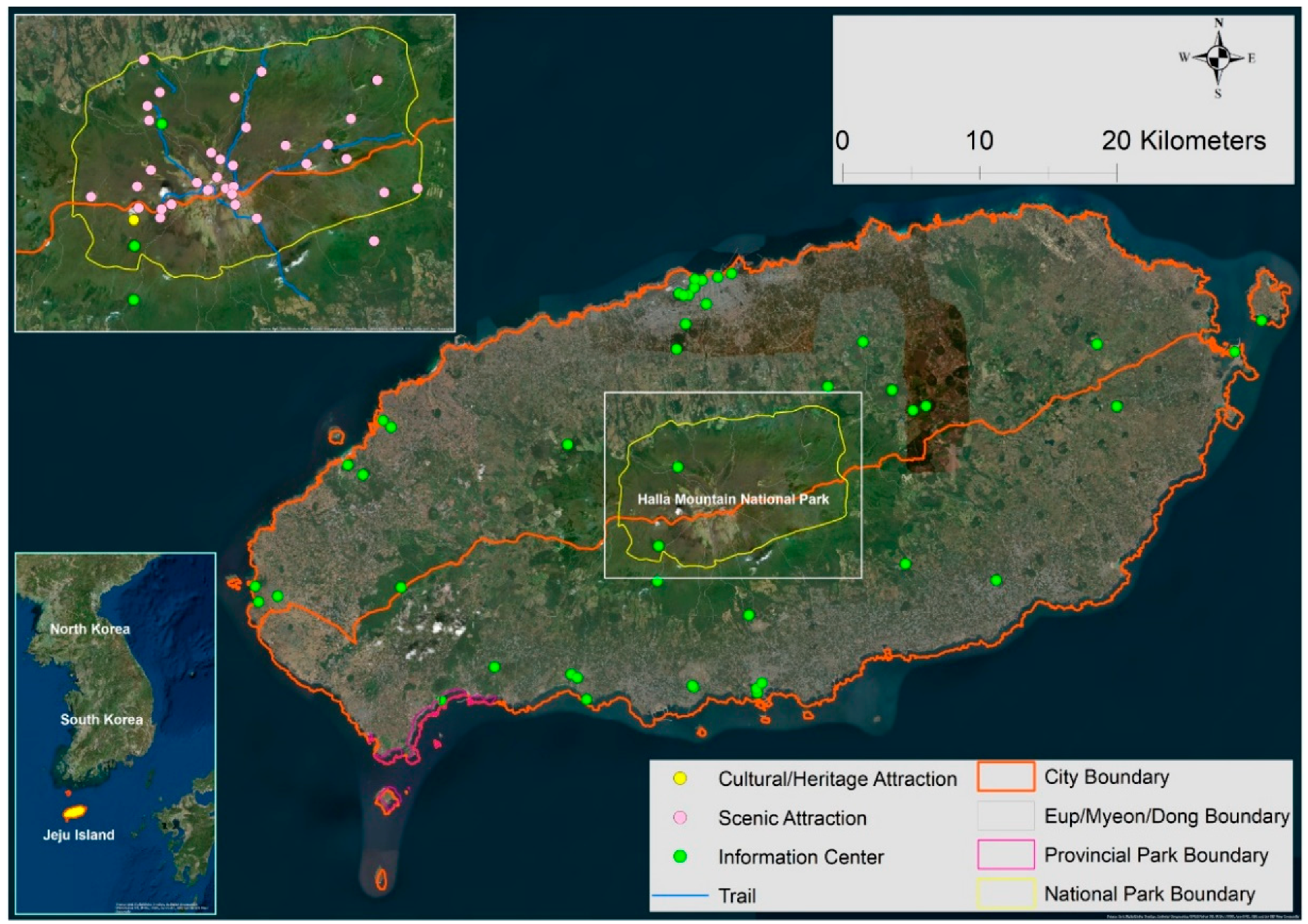

3.1. Research Site

3.2. Data Collection and Sample

3.3. Measures

4. Results

4.1. Sample Characteristics

4.2. Two-Step Analyses

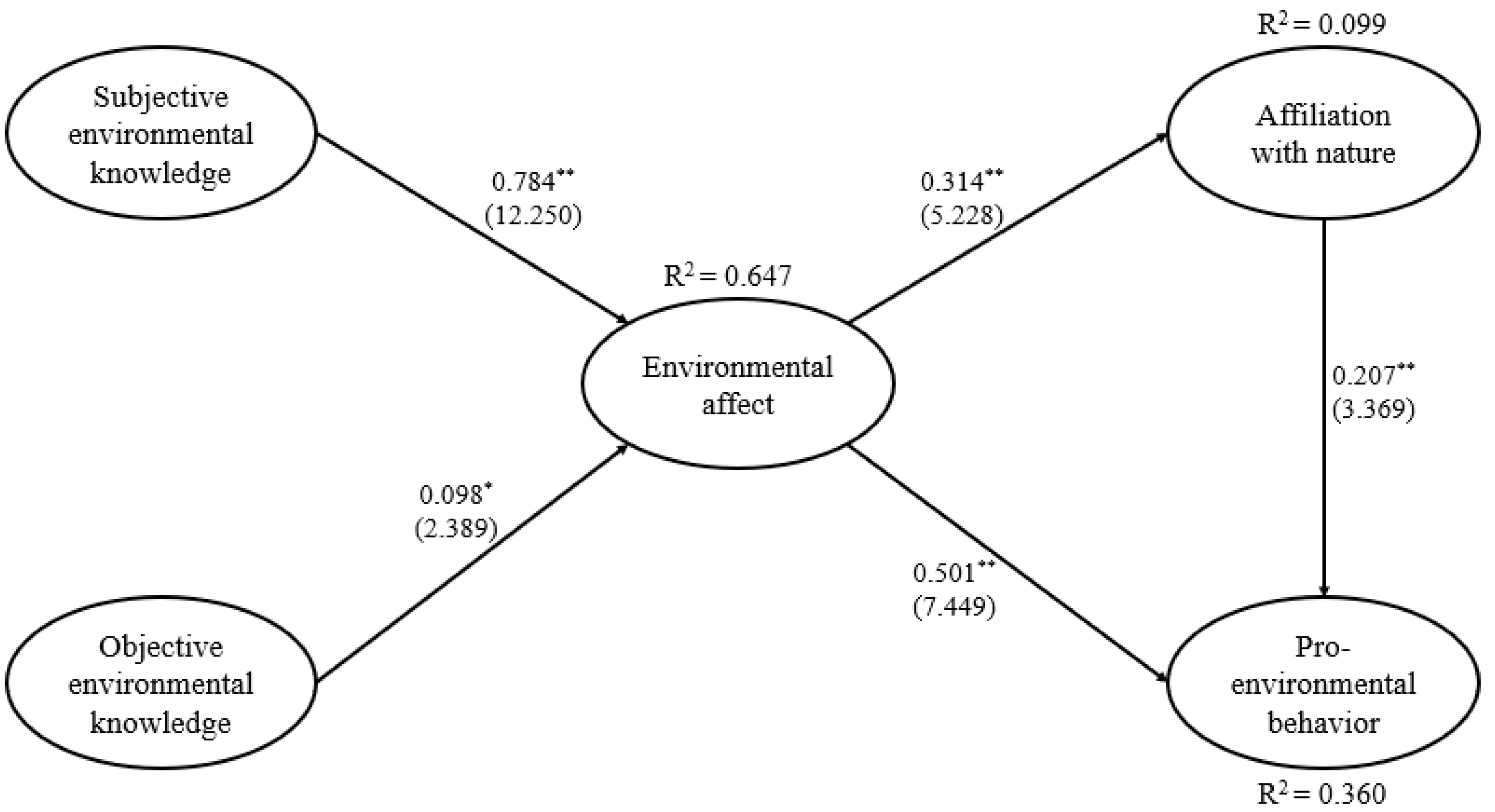

4.3. Structural Equation Modelling and Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion and Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thapa, B.; Lee, J. Visitor experience in Kafue National Park, Zambia. J. Ecotour. 2017, 16, 112–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessa, L.; Bennett, S.M.; Kliskey, A.D. Effects of knowledge, personal attribution and perception of ecosystem health on depreciative behaviors in the Intertidal Zone of Pacific Rim National Park and Reserve. J. Environ. Manag. 2003, 68, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Mirrilees, B.; Coghlan, A. Sustainable urban tourism: Understanding and developing visitor pro-environmental behaviours. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonge, J.; Ryan, M.M.; Moores, S.A.; Beckley, L.E. The effect of place attachment on pro-environmental behavioral intentions of visitors to Coastal Natural Area Tourist Destinations. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 730–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Thapa, B. Perceived value and flow experience: Application in a nature-based tourism context. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 8, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.H.; Yang, C.C. Conceptualizing and measuring environmentally responsible behaviors from the perspective of community-based tourists. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 454–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.H. The influence of recreation experience and environmental attitude on the environmentally responsible behavior of community-based tourists in Taiwan. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1063–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.M.; Wu, H.C. How do environmental knowledge, environmental sensitivity, and place attachment affect environmentally responsible behavior? An integrated approach for sustainable island tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 557–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, B. The mediation effect of outdoor recreation participation on environmental attitude-behavior correspondence. J. Environ. Educ. 2010, 41, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.M.; Wu, H.; Huang, L.M. The influence of place attachment on the relationship between destination attractiveness and environmentally responsible behavior for island tourism in Penghu, Taiwan. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 1166–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Manfredo, M.J. A theory of behavior change. Influ. Hum. Behav. 1992, 24, 29–50. [Google Scholar]

- Halpenny, E.A. Pro-environmental behaviours and park visitors: The effect of place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, R.; Packer, J.; Sutherland, L.A. Visitors’ memories of wildlife tourism: Implications for the design of powerful interpretive experiences. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 770–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, C. The Effects of Environmental Education on the Behaviour of SCUBA Divers: A Case Study from the British Virgin Islands. Unpublished Master’s Thesis, The University of Greenwich, London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Amyx, D.A.; DeJong, P.F.; Lin, X.; Chakraborty, G.; Wiener, J.L. Influencers of purchase intentions for ecologically safe products: An exploratory study. In AMA Winter Educators’ Conference Proceedings; American Marketing Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 1994; Volume 5, pp. 341–347. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, P.S.; Shih, L.H. Effective environmental management through environmental knowledge management. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 6, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, L.; Thapa, B. Visitor perspectives on sustainable tourism development in the Pitons Management Area World Heritage Site, St. Lucia. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2010, 12, 839–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, B.; Graefe, A.R.; Meyer, L.A. Moderator and mediator effects of scuba diving specialization on marine-based environmental knowledge-behavior contingency. J. Environ. Educ. 2005, 37, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurzinger, S.; Johansson, M. Environmental concern and knowledge of ecotourism among three groups of Swedish tourists. J. Travel Res. 2006, 45, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.C.; Lin, H.S. Exploring undergraduate students’ mental models of the environment: Are they related to environmental affect and behavior? J. Environ. Educ. 2015, 46, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bricker, K.S.; Kerstetter, D.L. Level of specialization and place attachment: An exploratory study of Whitewater recreationists. Leis. Sci. 2000, 22, 233–257. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, D.; Xu, F. Evolutionary and Socio-cultural Influences on Feelings and Attitudes towards Nature: A Cross-cultural Study. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Expose. Pretty and Polluted: Jeju Overfilling with Tourists. 2017. Available online: https://www.koreaexpose.com/jeju-pretty-polluted-overfilling-tourists/ (accessed on 5 May 2018).

- Jeju Special Self-Governing Provincial Tourism Association. 2016. Available online: http://www.visitjeju.or.kr/web/eng/iota01.do (accessed on 17 June 2018).

- Kwon, J.; Vogt, C.A. Identifying the role of cognitive, affective, and behavioral components in understanding residents’ attitudes toward place marketing. J. Travel Res. 2010, 49, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C.; Cave, J. Structuring destination image: A qualitative approach. J. Travel Res. 2005, 44, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, C.; Andereck, K. Destination perceptions across a vacation. J. Travel Res. 2003, 41, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, M.M. A hierarchical analysis of the green consciousness of the Egyptian consumer. Psychol. Mark. 2007, 24, 445–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, C.; Taghian, M.; Lamb, P. An empirical study on the influence of environmental labels on consumers. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2006, 11, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Möser, G. Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conraud-Koellner, E.; Rivas-Tovar, L.A. Study of green behavior with a focus on Mexican individuals. iBusiness 2009, 1, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aertsens, J.; Mondelaers, K.; Verbeke, W.; Buysse, J.; Van Huylenbroeck, G. The influence of subjective and objective knowledge on attitude, motivations and consumption of organic food. Br. Food J. 2011, 113, 1353–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brucks, M. The effects of product class knowledge on information search behavior. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeve-de Pauw, J.; Van Petergem, P. The effect of flemish eco-schools on student environmental knowledge, attitudes, and affect. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2011, 33, 1513–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kals, E.; Maes, J. Sustainable development and emotions. In Psychology of Sustainable Development; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 97–122. [Google Scholar]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R. Environmental attitudes and behavior of consumers in China: Survey findings and implications. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 1999, 11, 25–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.; Yam, E. Green movement in a newly industrializing area: A survey on the attitudes and behavior of Hong Kong citizens. J. Community Appl. Soc. 1995, 5, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beery, T.; Jönsson, K.I.; Elmberg, J. From environmental connectedness to sustainable futures: Topophilia and human affiliation with nature. Sustainability 2015, 7, 8837–8854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louv, R. Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder; Algonquin Books: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Junot, A.; Paquet, Y.; Martin-Krumm, C. Passion for outdoor activities and environmental behaviors: A look at emotions related to passionate activities. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 53, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.L.; Green, J.D.; Reed, A. Interdependence with the environment: Commitment, interconnectedness, and environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capaldi, C.A.; Dopko, R.L.; Zelenski, J.M. The relationship between nature connectedness and happiness: A meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, E.O. Biophilia; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Nabhan, G.P.; St Antoine, S. The Loss of Floral and Faunal Story: The Extinction of Experience. In The Biophilia Hypothesis; Kellert, R.S., Wilson, E.O., Eds.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1993; pp. 229–250. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.P.; Lin, Y.J. The relationship between environmental attitudes and behavior of ecotourism: A case study of Guandu Natural Park. J. Outdoor Recreat. Stud. 2001, 14, 15–36. [Google Scholar]

- Prayag, G.; Hosany, S.; Odeh, K. The role of tourists’ emotional experiences and satisfaction in understanding behavioral intention. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2013, 2, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W. Empathizing with nature: The effects of perspective taking on concern for environmental issues. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R. Experiencing Nature: Affective, Cognitive and Evaluative Development in Children. In Children and Nature: Psychological, Sociocultural and Evolutionary Investigation; Kahn, P.H., Jr., Kellert, S.R., Eds.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 117–151. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waugh, C.E.; Fredrickson, B.L. Nice to know you: Positive emotions, self-other overlap, and complex understanding in the formation of a new relationship. J. Posit. Psychol. 2006, 1, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, T.H. How recreation involvement, place attachment and conservation commitment affect environmentally responsible behavior. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 895–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissing-Olson, M.J.; Iyer, A.; Fielding, K.S.; Zacher, H. Relationships between daily affect and pro-environmental behavior at work: The moderating role of pro-environmental attitude. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 156–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griskevicius, V.; Tybur, J.M.; Van den Bergh, B. Going green to be seen: Status, reputation, and conspicuous conservation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 98, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisbet, E.K.; Zelenski, J.M.; Murphy, S.A. The nature relatedness scale: Linking individuals’ connection with nature to environmental concern and behavior. Environ. Behav. 2009, 41, 715–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S.; Thapa, B.; Kim, H. International tourists’ perceived sustainability of Jeju Island, South Korea. Sustainability 2018, 10, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Stepchenkova, S. Understanding destination personality through visitors’ experience: A cross-cultural perspective. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, S.J.; Overton, T.S. Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. J. Mark. Res. 1977, 14, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, J.P.; Spell, C.S.; Nyamori, R.O. Correlates and consequences of high involvement work practices: The role of competitive strategy. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Man. 2002, 13, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, J.C.; Groothuis, P.A.; Blomquist, G.C. Testing for non-response and sample selection bias in contingent valuation. Econ. Lett. 1993, 41, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westland, J.C. Lower bounds on sample size in structural equation modeling. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2010, 9, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsóka, Á.; Szerényi, Z.M.; Széchy, A.; Kocsis, T. Greening due to environmental education? Environmental knowledge, attitudes, consumer behavior and everyday pro-environmental activities of Hungarian high school and university students. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 48, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonsky, M.J.; Vocino, A.; Grau, S.L.; Garma, R.; Ferdous, A.S. The Impact of general and carbon-related environmental knowledge on attitudes and behaviour of US consumers. J. Mark. Manag. 2012, 28, 238–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanchanapibul, M.; Lacka, E.; Wang, X.; Chan, H.K. An empirical investigation of green purchase behaviour among the Young Generation. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 66, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K.; Choi, J.G.; Kim, M.S.; Ahn, Y.G.; Katz-Gerro, T. Explaining pro-environmental behaviors with environmentally relevant variables: A survey in Korea. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 6, 8677–8690. [Google Scholar]

- Richer, S.F.; Vallerand, R.J. Construction and validation of the social belonging scale (SAS). Eur. Rev. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 48, 129–138. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, Y.T.H.; Lee, W.I.; Chen, T.H. Environmentally responsible behavior in ecotourism: Antecedents and implications. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.; Bernstenin, I. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Assumptions and comparative strengths of the two-step approach: Comment on Fornell and Yi. Sociol. Methods Res. 1992, 20, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bone, P.F.; Sharma, S.; Shimp, T.A. A bootstrap procedure for evaluating goodness-of-fit indices of structural equation and confirmatory factor models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1989, 38, 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Stepchenkova, S. Examining the impact of experiential value on emotions, self-connective attachment, and brand loyalty in Korean family restaurants. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2018, 19, 298–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, H.H.; Falk, H.; Hammerschmidt, M. eTransQual: A transaction process-based approach for capturing service quality in online shopping. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 866–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.K.; Choi, J.; Moon, B.Y.; Babin, B.J. Codes of ethics, corporate philanthropy, and employee responses. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 39, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.C.; Yeh, S.S.; Huan, T.C. Enduring involvement of scuba divers and its relations to their environmental knowledge and environmental behavior. Int. J. Asian Tour. Manag. 2010, 1, 42–53. [Google Scholar]

- House, L.; Lusk, J.; Bruce Traill, W.; Moore, M.; Calli, C.; Morrow, B.; Yee, W. Objective and subjective knowledge: Impacts on consumer demand for genetically modified foods in the United States and the European Union. AgBioForum 2004, 7, 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Oviedo-García, M.Á.; Castellanos-Verdugo, M.; Vega-Vázquez, M.; Orgaz-Agüera, F. The mediating roles of the overall perceived value of the ecotourism site and attitudes towards ecotourism in sustainability through the key relationship ecotourism knowledge-ecotourist satisfaction. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 19, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restall, B.; Conrad, E. A literature review of connectedness to nature and its potential for environmental management. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 159, 264–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, S. Environmental Identity: Conceptual and Operational Definition. In Identity and the Natural Environment: The Psychological Significance of Nature; Clayton, S., Opotow, S., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Baral, N.; Hazen, H.; Thapa, B. Visitor perceptions of World Heritage values at Sagarmatha (Mt. Everest) National Park, Nepal. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1494–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Barre, S. Wilderness and cultural tour guides, place identity and sustainable tourism in remote areas. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 825–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.Y.; Lau, L.B. Antecedents of green purchases: A survey in China. J. Consum. Mark. 2000, 17, 338–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Variables | Frequency | Percent (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 137 | 45.1 |

| Male | 167 | 54.9 | |

| Age | Below 29 | 128 | 42.1 |

| 30–39 | 71 | 23.4 | |

| 40–49 | 78 | 25.7 | |

| Over 50 | 26 | 8.6 | |

| Education | High school | 107 | 35.2 |

| College | 39 | 12.8 | |

| University | 123 | 40.5 | |

| Graduate school | 27 | 8.9 | |

| Occupation | Students | 66 | 21.7 |

| Office workers | 67 | 22.0 | |

| Professionals | 42 | 13.8 | |

| Service | 33 | 10.9 | |

| Technical workers | 58 | 19.1 | |

| Housewives | 23 | 7.6 | |

| Miscellaneous | 15 | 4.9 | |

| Annual household income | Below $36,000 | 101 | 33.2 |

| $36,001–$48,000 | 104 | 34.2 | |

| $48,001–$60,000 | 27 | 8.9 | |

| $60,001–$72,000 | 42 | 13.8 | |

| Over $72,000 | 30 | 9.9 |

| Constructs and Items | Standardized Factor Loading | t-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Subjective environmental knowledge (α = 0.876) | ||

| I am very knowledgeable about environmental issues. | 0.750 | Fixed |

| I understand the environmental phrases and symbols noted on product packages. | 0.914 | 16.030 |

| I know that I buy products that are environmentally safe. | 0.856 | 15.185 |

| I know more about recycling than an average person. | - | - |

| Environmental affect (α = 0.924) | ||

| It frightens me to think that much of the food I eat is contaminated with pesticides during this trip. | 0.854 | Fixed |

| It genuinely infuriates me to think that the government doesn’t do more to help control pollution at this destination. | 0.874 | 19.958 |

| I become incensed when I think about the harm being done to this destination’s plants and animals by pollution. | 0.899 | 20.995 |

| I get frustrated and angry when I think of the ways the tourism industry causes pollution. | 0.847 | 18.904 |

| Nature affiliation (α = 0.866) | ||

| I feel attached to nature during this trip. | 0.934 | Fixed |

| I can relate with nature during this trip. | 0.934 | 22.581 |

| I feel united with nature during this trip. | - | - |

| I feel close to nature during this trip. | 0.670 | 13.953 |

| I feel like a friend of nature during this trip. | - | - |

| Pro-environmental behavior (α = 0.774) | ||

| I accept the control policy not to enter the wetland. | 0.757 | Fixed |

| I help to maintain the local environmental quality. | 0.696 | 10.636 |

| I report any environmental destruction or pollution to the park manager and/or administration. | 0.608 | 9.428 |

| I try not to disrupt the fauna and flora during my travel. | 0.690 | 10.570 |

| Objective environmental knowledge 1 |

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Subjective environmental knowledge | 1 | ||||

| 2. Objective environmental knowledge | 0.129 ** (0.016) | 1 | |||

| 3. Environmental affect | 0.712 ** (0.507) | 0.179 ** (0.032) | 1 | ||

| 4. Nature affiliation | 0.247 ** (0.061) | 0.056 (0.003) | 0.299 ** (0.089) | 1 | |

| 5. Pro-environmental behavior | 0.169 ** (0.029) | 0.077 (0.006) | 0.261 ** (0.068) | 0.542 ** (0.294) | 1 |

| Mean | 5.640 | 1.345 | 5.668 | 5.778 | 5.388 |

| SD | 1.127 | 1.035 | 1.067 | 1.200 | 0.983 |

| CCR | 0.880 | - | 0.925 | 0.889 | 0.783 |

| AVE | 0.710 | - | 0.755 | 0.731 | 0.476 |

| Path | Standardized Estimates | t-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Subjective environmental knowledge → Environmental affect | 0.786 ** | 12.278 |

| Objective environmental knowledge → Environmental affect | 0.096 * | 2.344 |

| Environmental affect → Nature affiliation | 0.314 ** | 5.230 |

| Environmental affect → Pro-environmental behavior | 0.501 ** | 7.449 |

| Nature affiliation → Pro-environmental behavior | 0.207 ** | 3.367 |

| Endogenous variables | SMC (R2) | |

| Environmental affect | 0.647 | |

| Nature affiliation | 0.099 | |

| Pro-environmental behavior | 0.360 |

| Path | Indirect Effect | LL CIs (95%) | UL CIs (95%) | Z-Value | Mediating Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective environmental knowledge → Environmental affect → Nature affiliation | 0.247 ** | 0.157 | 0.335 | 2.239 ** | Full mediator |

| Objective environmental knowledge → Environmental affect → Nature affiliation | 0.030 * | 0.006 | 0.062 | 1.528 | Not significant |

| Subjective environmental knowledge → Environmental affect → Pro-environmental behavior | 0.445 ** | 0.344 | 0.526 | 4.046 ** | Full mediator |

| Objective environmental knowledge → Environmental affect → Pro-environmental behavior | 0.055 * | 0.009 | 0.109 | 1.967 * | Full mediator |

| Environmental affect → Nature affiliation → Pro-environmental behavior | 0.065 ** | 0.026 | 0.118 | 1.852 | Not significant |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, M.-S.; Kim, J.; Thapa, B. Influence of Environmental Knowledge on Affect, Nature Affiliation and Pro-Environmental Behaviors among Tourists. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3109. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10093109

Kim M-S, Kim J, Thapa B. Influence of Environmental Knowledge on Affect, Nature Affiliation and Pro-Environmental Behaviors among Tourists. Sustainability. 2018; 10(9):3109. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10093109

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Min-Seong, Jinwon Kim, and Brijesh Thapa. 2018. "Influence of Environmental Knowledge on Affect, Nature Affiliation and Pro-Environmental Behaviors among Tourists" Sustainability 10, no. 9: 3109. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10093109

APA StyleKim, M.-S., Kim, J., & Thapa, B. (2018). Influence of Environmental Knowledge on Affect, Nature Affiliation and Pro-Environmental Behaviors among Tourists. Sustainability, 10(9), 3109. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10093109