State Control Versus Hybrid Land Markets: Planning and Urban Development in Transitional Hanoi, Vietnam

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Locality and Methods

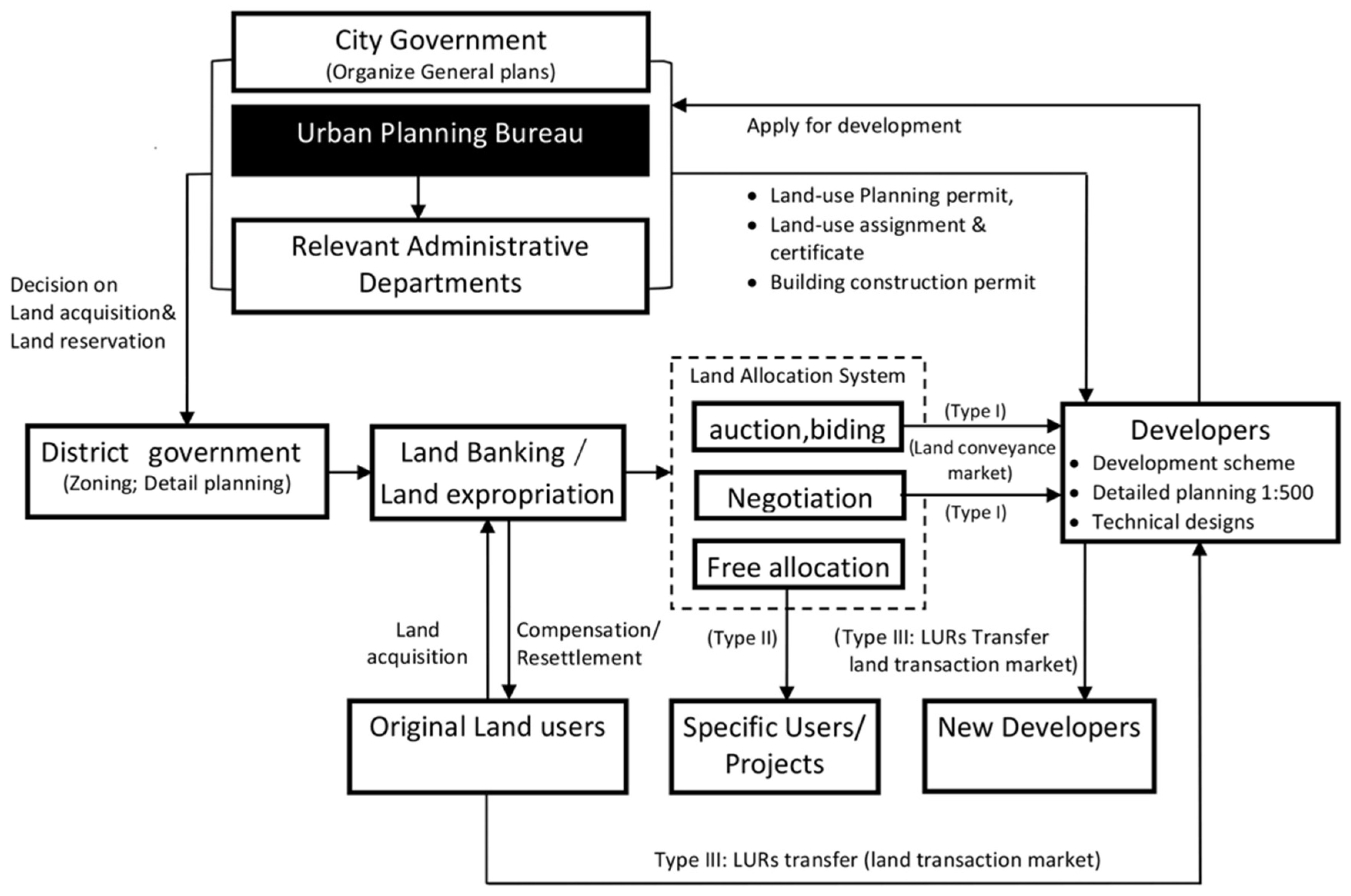

3. Planning During a Time of Transition: Planning Control and the State Ideology

3.1. Conceptual Framework for Urban Planning in Vietnam

3.2. Urban Planning in the Pre-Reform Era

3.3. Changes in the Planning System during the Post-Reform Era

4. Urban Development in Transition: Hybrid Land Markets in Hanoi

4.1. Spontaneous Development and the Informal Land Market

4.2. Planned Urban Projects and the Formal Land Market

4.3. Hybrid Land Markets Versus Planning Control

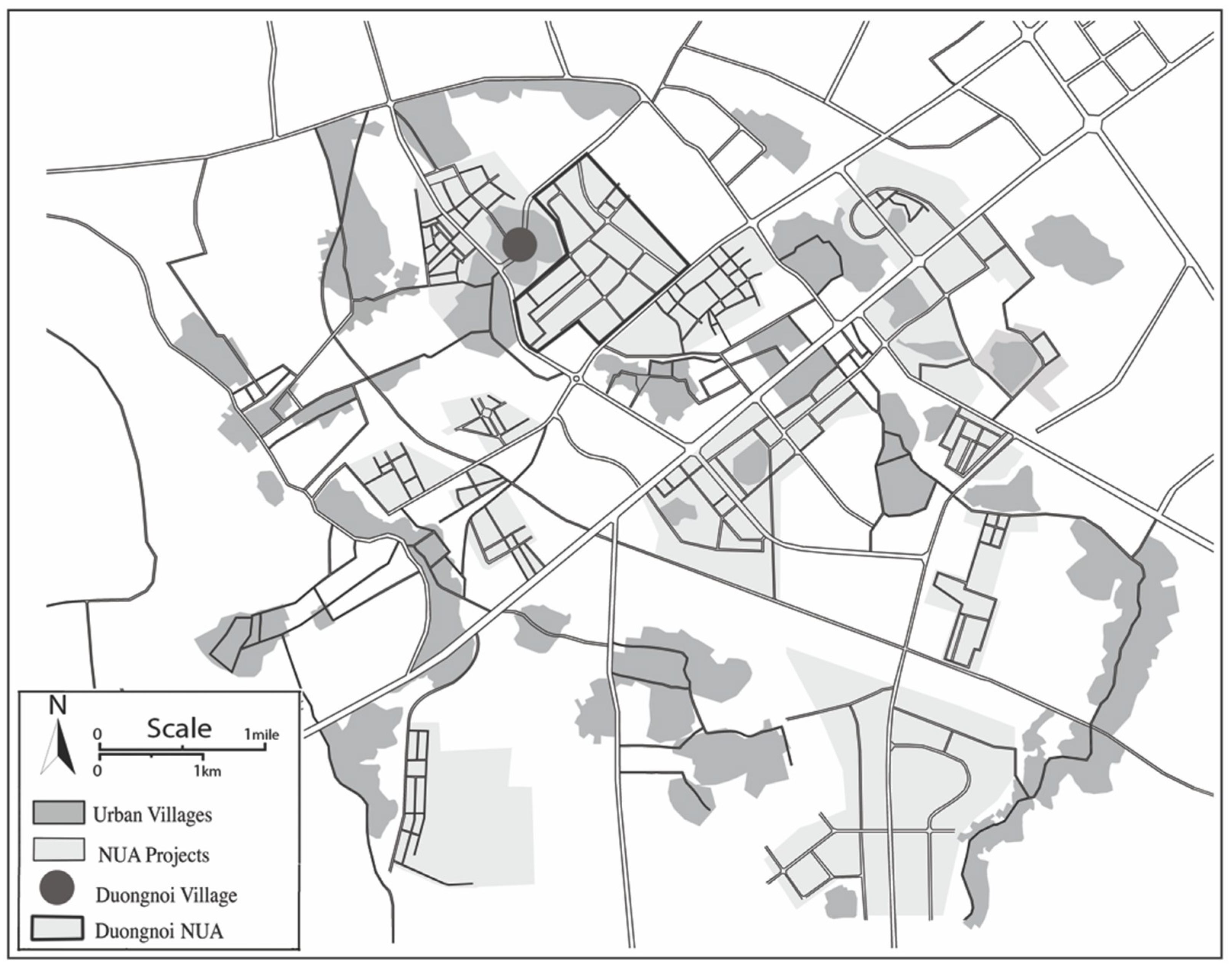

5. The Case of Urban Development and Planning in Ha Dong District, Hanoi

5.1. Planning Constraints for NUA Projects

“Most of the NUA projects are applied by the developers according to approved planning. But even when actual developments don’t match the planning, the developers will apply for a planning readjustment. In practice, this situation frequently happens. It shows us the fact that urban development is private-led but not state-led. Obviously, this type of development is profit-driven and speculative, they (developers) do not consider the public interests or the real housing demand”.(Interview with official in DPA, Hanoi, 8 April 2016)

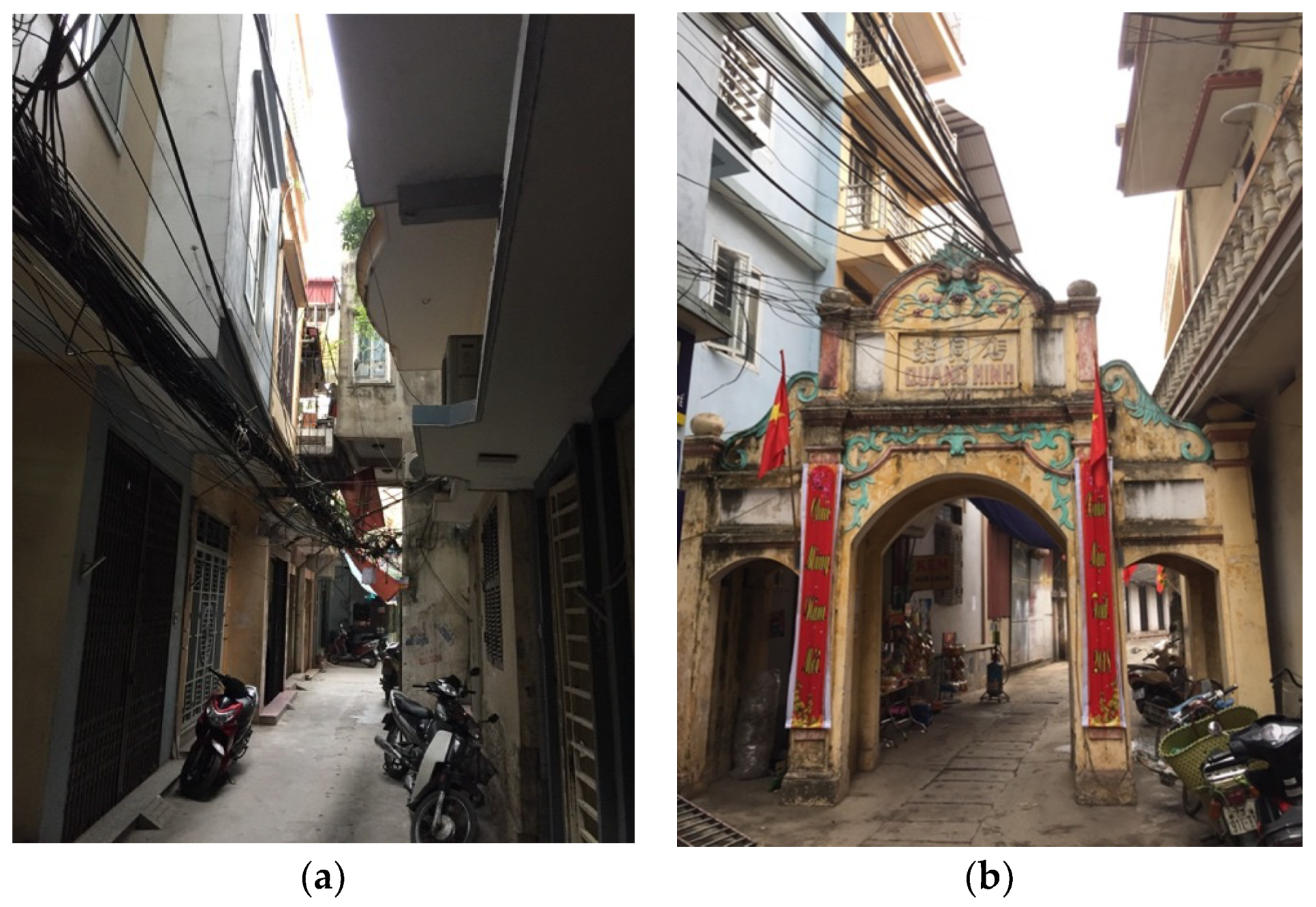

5.2. Uncontrolled Development in Peri-Urban Villages

“They (villagers) think that if numerous families simultaneously occupy the land on a large scale and if they transfer housing to the migrants, the government will not be capable of removing their constructions”.(interview with official in Ha Dong, Hanoi, 3 June 2017)

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Quang, N.; Kammeier, H.D. Changes in the political economy of Vietnam and their impacts on the built environment of Hanoi. Cities 2002, 19, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai Anh, T.; Kidokoro, T.; Seta, F. Practices of detailed planning in Hanoi city under transition economy uncertainty of detailed planning in Cau giay district. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference Symposium on City Planning, Sendai, Japan, 23 August 2013; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura, S.; Nguyen, T.H.; Truong, T.K. New Approach and Issues for the Urban Planning System in Vietnam—The Practice of the Newly Formulated Urban Planning Regulations in Ho Chi Minh City. Urban Reg. Plan. Rev. 2017, 4, 58–70. [Google Scholar]

- Huynh, D. The misuse of urban planning in Ho Chi Minh City. Habitat Int. 2015, 48, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Horen, B. City profile Hanoi. Cities 2005, 22, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leducq, D.; Scarwell, H. The new Hanoi: Opportunities and challenges for future urban development. Cities 2018, 72, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, J.E.; Jenkins, P.; Nielsen, M. Who plans the African city? A case study of Maputo: Part 1—The structural context. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2015, 37, 331–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAuslan, P. Land, Law and Planning; Weidenfeld and Nicholson: London, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, E.J.; Godschalk, D. Twentieth century land use planning: A Stalwart family tree. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1995, 61, 365–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, P.; Shaw, T. Changing Meanings of ‘Environment’ in the British Planning System. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 1994, 19, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janin Rivolin, U. Global crisis and the systems of spatial governance and planning: An European comparison. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2017, 25, 994–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamarche, F. Property Development and the Economic Foundations of the Urban Question. In Urban Sociology: Critical Essays; Pickvance, C.G., Ed.; Tavistock Publication: Andover, MA, USA, 1976; pp. 85–118. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Labor, Capital, and Class Struggle around the Built Environment in Advanced Capitalist Societies. Politics Soc. 1976, 6, 265–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldarice, O. Reconsidering Welfare Policies in Times of Crisis: Perspective for European Cities; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P.; Barrett, S.M. Structure and agency in land and property development processes: Some ideas for research. Urban Stud. 1990, 27, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foglesong, R. Planning the Capitalist City: The Colonial Era to the 1920s; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Needham, B. Planning, Law and Economics: The Rules We Make for Using Land; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- McGee, T.G. Interrogating the production of urban space in China and Vietnam under market socialism. Asia Pac. Viewp. 2009, 50, 228–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainsbourough, M. Vietnam: Rethinking the State; Zed Books: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J. Local Developmental State and Order in China’s Urban Development during Transition. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2004, 28, 424–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.L.; Duan, J.; Zhang, G.Q. Land Politics under Market Socialism: The State, Land Policies, and Rural–Urban Land Conversion in China and Vietnam. Land 2018, 7, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labbé, D.; Musil, C. Periurban land redevelopment in Vietnam under market socialism. Urban Stud. 2014, 51, 1146–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, W. Russians on the Red River: The Soviet impact on Hanoi’s townscape, 1955–1990. Eur. Asia Stud. 1995, 47, 443–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.G. Fiscal decentralization in Vietnam: Emerging issues. Hitotsub. J. Econ. 2000, 41, 163–177. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. East Asia Decentralizes: Making Local Government Work; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gough, K.V.; Tran, H.A. Changing housing policy in Vietnam: Emerging inequalities in a residential area of Hanoi. Cities 2009, 26, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudreau, J.A.; Gilbert, L.; Labbé, D. Uneven state formalization and peri-urban housing production in Hanoi and Mexico City: Comparative reflections from the global South. Environ. Plan. A 2016, 48, 2383–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phe, H.H. Investment in residential property: Taxonomy of home improvers in central Hanoi. Habitat Int. 2002, 26, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Vietnam Urbanization Review: Technical Assistance Report; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Drakakis-Smith, D.; Dixon, C. Sustainable urbanization in Vietnam. Geoforum 1997, 28, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geertman, S. The Self-Organizing City in Vietnam; Processes of Change and Transformation in Housing in Hanoi. Ph.D. Thesis, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, D. Illegal Construction in Hanoi and Hanoi’s Ward. Eur. J. East Asian Stud. 2004, 3, 337–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, T.D.; Vinh, N.Q. Socio-Economic Impacts of ‘Doi Moi’ on Urban Housing in Vietnam; Social Sciences Publishing House: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Truong, T.T.; Perera, R. Intermediate levels of property rights and the emerging housing market in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Land Use Policy 2011, 28, 124–138. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, H.A.; Yip, N.M. A regime of informality? “Informal housing” and the state-society relationship in transitional Vietnam. Trialog 123 2017, 4, 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, D.; Kwon, Y. In-Migration and Housing Choice in Ho Chi Minh City: Toward Sustainable Housing Development in Vietnam. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leaf, M. Vietnam’s Urban Edge: The administration of urban development in Hanoi. Third World Plan. Rev. 1999, 21, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.A. Urban Space Production in Transition: The Cases of the New Urban Areas of Hanoi. Urban Policy Res. 2015, 33, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embassy of Denmark; World Bank; Embassy of Sweden. Recognizing and Reducing Corruption Risks in Land Management in Vietnam; The National Political Publishing House: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Truong, T.T.; Perera, R. Consequences of the two-price system for land in the land and housing market in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Habitat Int. 2011, 35, 30–39. [Google Scholar]

- Phuc, N.Q.; Westen, A.C.M.V.; Zoomers, A. Agricultural land for urban development: The process of land conversion in Central Vietnam. Habitat Int. 2014, 41, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vn Express. Vietnam Arrests Top Ex-Officials as Corruption Crackdown Continues. Available online: https://e.vnexpress.net/news/news/vietnam-arrests-top-ex-officials-as-corruption-crackdown-continues-3738134.html (accessed on 8 July 2018).

- Vietnam News. Land Corruption on the Rise: NEU Research. Available online: https://vietnamnews.vn/society/347664/land-corruption-on-the-rise-neu-research.html (accessed on 10 July 2018).

- Tuoi Tre News. Build-Transfer Contracts Sow Fertile Ground for Corruption in Vietnam: Conference. Available online: https://tuoitrenews.vn/news/business/20171020/buildtransfer-contracts-sow-fertile-ground-for-corruption-in-vietnam-conference/42172.html (accessed on 14 July 2018).

- Nguyen, T.B.; Van der Krabben, E.; Spencer, J.H.; Truong, K.T. Collaborative development: Capturing the public value in private real estate development projects in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Cities 2017, 68, 104–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCluskey, W.J.; Trinh, H. Property tax reform in Vietnam: Options, direction and evaluation. Land Use Policy 2013, 30, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| City | Agricultural Land | Rural Residential Land | Urban Residential Land | Specialized Land | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of LURCs Issued | Area Covered (ha) | % of Total Land Area | Number of LURCs Issued | Area Cover (ha) | % of Total Land Area | Number of LURCs Issued | Area Covered (ha) | % of Total Land Area | Number of LURCs Issued | Area Covered (ha) | % of Total Land Area | |

| Hanoi | 642,324 | 132,277 | 86.79 | 498,816 | 15,636 | 56.0 | 244,139 | 2634 | 33.89 | 3383 | 8150 | 34.39 |

| Ho Chi Minh | 176,726 | 69,831 | 96.58 | 20,028 | 1463.71 | 19.52 | 555,580 | 6821 | 42.47 | 5239 | 9871 | 64.93 |

| Year | 2001 | 2003 | 2005 | 2007 | 2009 | 2011 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State-Driven | 12.28% | 21.75% | 14.32% | 12.20% | 17.66% | 1.13% | 2.25% |

| Self-built | 61.88% | 48.48% | 58.68% | 69.74% | 59.98% | 67.27% | 45.07% |

| Commercial | 25.84% | 29.77% | 27% | 18.06% | 22.36% | 31.6% | 52.68% |

| Year | Local Government Revenue as % of GDP | Budgetary Investment in Capital Construction as % of GDP | Budgetary Investment as % of Total Investment in Capital Construction |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 10.29 | 1.41 | _ _ |

| 2000 | 7.53 | 2.92 | _ _ |

| 2005 | 15.25 | 6.82 | 14.88 |

| 2010 | 13.78 | 6.65 | 12.18 |

| 2015 | 17.80 | 4.73 | 10.48 |

| Name of NUA | Size of Development (ha) | Year | Occupation Rate by Household (%) | Land Allocation Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mo Lao | 64 | 2005 | ≥90 | Negotiated |

| Van Quan | 61 | 2003 | ≥90 | Negotiated |

| Van Khe | 23 | 2007 | ≥30 | Negotiated |

| Duong Noi | 200 | 2008 | ≤10 | Built-Transfer |

| Geleximco | 135 | 2010 | ≤10 | Built-Transfer |

| Van Phu | 94.1 | 2007 | ≤30 | Built-Transfer |

| Xa La | 20 | 2007 | ≥90 | Negotiated |

| Thanh Ha | 416 | 2008 | ≤5 | Built-Transfer |

| Kien Hung | 25 | 2010 | ≤30 | Negotiated |

| Phu Luong | 36 | 2008 | ≤10 | Negotiated |

| Đong Mai | 214.8 | 2009 | ≤5 | Negotiated |

| Park city | 77 | 2010 | ≤10 | Negotiated |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nguyen, H.L.; Duan, J.; Liu, J.H. State Control Versus Hybrid Land Markets: Planning and Urban Development in Transitional Hanoi, Vietnam. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2993. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10092993

Nguyen HL, Duan J, Liu JH. State Control Versus Hybrid Land Markets: Planning and Urban Development in Transitional Hanoi, Vietnam. Sustainability. 2018; 10(9):2993. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10092993

Chicago/Turabian StyleNguyen, Hoang Linh, Jin Duan, and Jin Hua Liu. 2018. "State Control Versus Hybrid Land Markets: Planning and Urban Development in Transitional Hanoi, Vietnam" Sustainability 10, no. 9: 2993. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10092993

APA StyleNguyen, H. L., Duan, J., & Liu, J. H. (2018). State Control Versus Hybrid Land Markets: Planning and Urban Development in Transitional Hanoi, Vietnam. Sustainability, 10(9), 2993. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10092993