Does Urban Agriculture Improve Food Security? Examining the Nexus of Food Access and Distribution of Urban Produced Foods in the United States: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

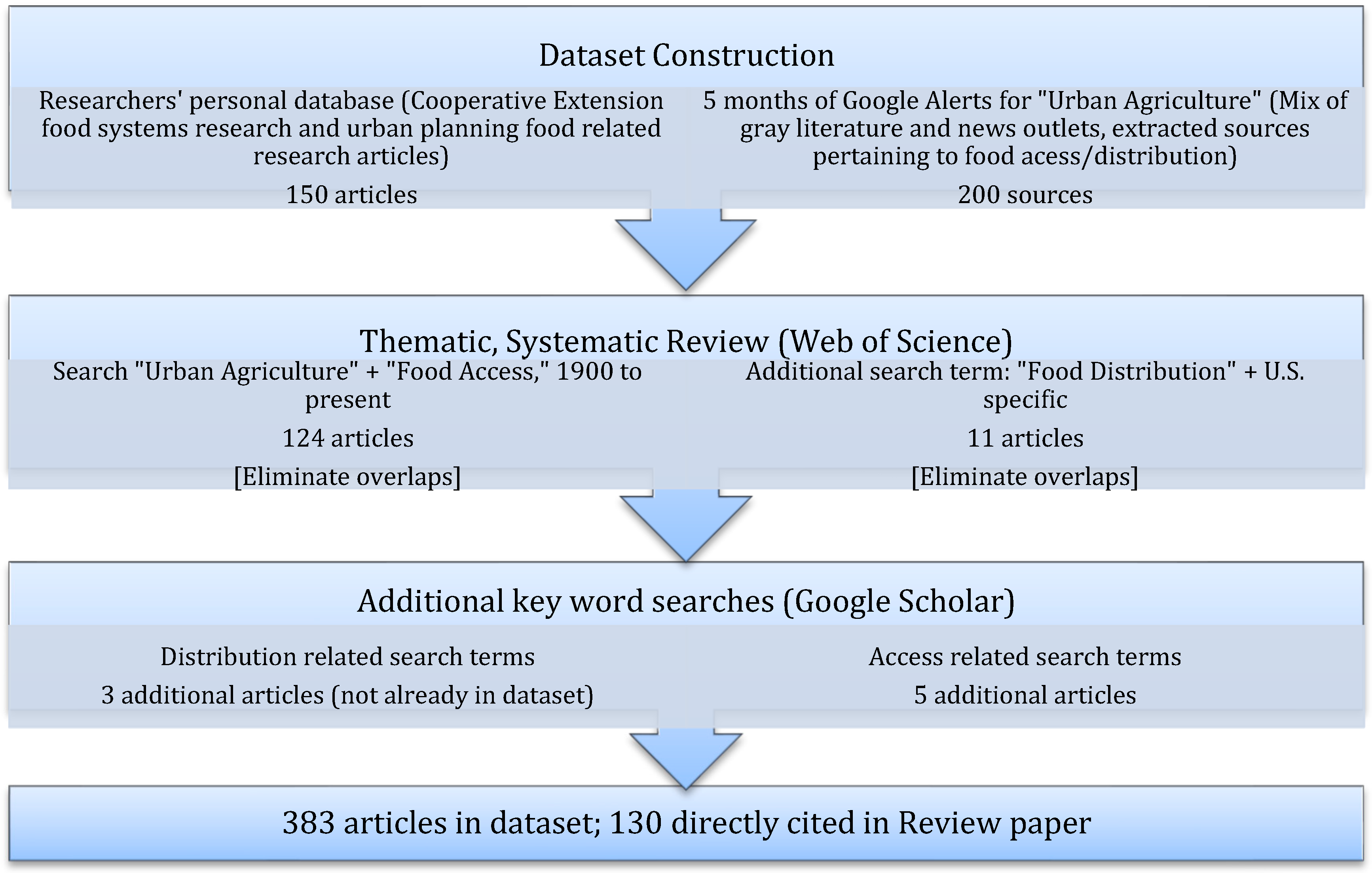

2. Materials and Methods

3. Food Access: Do Low-Income Urban Consumers Access Urban Produced Food?

3.1. Spatial Analyses Highlight Productive Potential and Uneven Distribution of UA

3.2. Cost of Urban Produced Foods

3.3. Cost of Land and Labor

3.4. Culture, Education, and Innovative Urban Food Sources

| Diversified revenue streams are key to the success of urban agriculture initiatives providing access to food insecure communities. Additional evidence of success in the literature includes examples of sustained operations over time (allowing sustained access), and evaluations (both internal and external) that demonstrate food access in underserved communities. | ||

Sustained operations over time:

| Multiple revenue streams: (grants, donations, and in-kind contributions, allows farms to provide a substantial percentage of the food they grow to low-income households, via donations or discounted sales). | Evaluations demonstrating food access:

|

| These organizations do not rely on produce sales to cover production expenses, but rather cross-subsidize operating expenses and salaries with revenues from grants, donations, educational activities, or other services offered [73]. They combine mission-driven values, education, and public “goods” with growing food in order to attract investment for their inherent value to a community; they are seen as desirable and “worthy” places to volunteer one’s time; and they attract numerous partnerships with other businesses, schools, or non-profits within the city. Building connectivity through strong social relationships with nonprofits, schools, donors, and city governments appears to be a promising mechanism for improving food access while meeting the operating expenses of an urban agriculture operation [72]. A particularly well-connected, city supported network of UA is the NYC GreenThumb program, a network of over 550 community gardens with employees/youth interns, tools and resources provided through the City. Neighborhood residents manage gardens, enabling sovereignty over planting decisions and crop varieties. | ||

4. Food Distribution: How Do Urban Farmers Get Their Produce to The Consumer?

4.1. Distribution via Corner Stores and Supermarkets

4.2. Distribution via Farmers Markets

4.3. Theorizing the Distribution “Foodshed” via Alternative Distribution Channels

5. Access and Distribution

5.1. Economic Viability

| Case Study 1: Growing Power |

| Growing Power in Milwaukee, WI, was a leader in the community or “good food” movement [36]. Operating as a nonprofit between 1993 and 2018, the organization, founded by basketball star Will Allen, “expanded people’s ideas about what was possible in local food production and youth education” [89]. The son of sharecroppers, Allen has a passion for vegetables, composting, and youth mentorship that he channeled into Growing Power, making it a bastion of urban food production, healthy soil creation, urban revitalization, and youth empowerment. In 2008 he was awarded a MacArthur Genius Award worth $500,000, which fueled the organization’s growth and construction of hoop houses for aquaponics systems across the city. He was operating over 100 hoop houses and distributing food to over 10,000 people via below-market-cost CSAs, farmers markets, sales to schools, and restaurants, as well as managing flourishing vermicomposting and aquaponics programs, and hosting the annual Growing Food and Justice for All conferences organized by his daughter since 2008. These are known for their efforts to “forge new partnerships around food system self-determination for low-income communities and communities of color… [placing] racism front and center in the context of food and agriculture” [111]. Growing Power, Inc. operations produced 40 million pounds of food and over 100,000 fish annually at its peak, selling over 40,000 pounds of carrots to schools in 2014, representing the largest sale in farm-to-school according to the USDA [112]. Visitors came from around the world, adapting Allen’s knowledge of growing, composting, aquaponics, and closed loop systems (for growing both good food and good people) for their own communities. The organization received additional large grants from the Kellogg Foundation and WalMart in 2011 and 2012, but by 2014 revenue could not keep pace with expenses related to growing staff (over 200 people) and expanded operations. |

| Allegations of “founder’s syndrome” and Allen’s inability to surround himself with a high-functioning organizational management team are both cited as reasons behind Growing Power, Inc.’s ultimate dissolution in 2018 [89]. Allen, who considers farming a form of personal therapy and has always been growing “more than food,” continues to grow, now under the for-profit enterprise “Will Allen’s Roadside Farm.” While now a for-profit business, Allen continues to prioritize serving underserved communities, teaching kids and young people with disabilities, and centering the social impact of his work. While he has said that operating a commercially viable urban farm as a nonprofit “cannot be done,” there are others who still maintain that “a nonprofit, structured properly, or a co-op can be successful in larger-scale urban agriculture projects” [112]. |

| There are lessons to be learned from this case study for those evaluating the impacts of urban agriculture. How do we evaluate economic outcomes in relation to social and educational outcomes? While Growing Power, Inc. may be considered a “failure” to learn from in economic viability terms (due to lack of board member oversight and insufficient collaborations), it is certainly a timeless social success in terms of the individuals it has inspired who are now leaders in their own urban food system and social justice enterprises, the education it has provided to thousands of youth, and the infrastructure of hoop houses, aquaponic greenhouses, and food producing sites that remain in place across Milwaukee and around the world. |

| Case Study 2: The Food Project |

| The Food Project (TFP) in Boston, MA has operated for over 25 years as a nonprofit with an operating budget over $2 million. The organization operates several farm sites in Boston as well as the surrounding suburbs in Lynn, provides food to low income and minority neighborhoods, and offers paid summer work and internships to high school students. While they do generate revenue from food production, this revenue stream is marginal compared to incomes from grants, donations, investments, and educational services provided by the organization, and food sales cover less than half of the expenses related to food production. TFP has been “able to successfully combine substantial commercial agriculture production ($412,000 in annual revenue, FY2014) with mission-driven, non-profit work. TFP’s economic practices are non-capitalist, as are the logics and metrics it uses to allocate resources and assess success” [73]. They pride themselves on going beyond “mere food access” with their Real Food Hub model, combining TFP’s expertise in sustainable agriculture cultivation and youth development with partner organizations’ education, family services, and community development expertise to “give families the tools, skills, and resources to define healthy food options and practices that build physical, social, and cultural well-being” [73]. Compared to other “good food” organizations in Boston that struggle to provide living wage jobs, speaking to the significant challenges to economic viability that any urban agriculture initiative faces, TFP’s “economic viability and sustainability rest squarely upon its ongoing ability to convince donors (of both money and time) that it is engaging in practices and achieving outcomes that are worthy of their ongoing support” [73]. However, the question of wealth transfers across economic class lines (wealthy to lower income), rather than truly reciprocal economic transfers, continues to plague the organization’s quest for increased economic equity in the food system at large. Along with many organizations that rely on volunteer and unpaid food work, the question of whether this is non-exploitative and anti-capitalist rests on the nature of the work, degree of choice involved among participants, who can afford the time and ability to volunteer, and ultimate goals of the organization [73]. |

5.2. Policy and Planning Models

5.3. Civic Engagement and Advocacy

6. Reframing UA as A Public Good: Using an Equity and Systems Lens to Integrate UA into Municipal Planning and Policy Efforts

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McClintock, N.; Miewald, C.; McCann, E. The Politics of Urban Agriculture: Sustainability, Governance, and Contestation. In The Routledge Handbook on Spaces of Urban Politics; Jonas, A.E.G., Miller, B., Wilson, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, J.R.; Lovell, S.T. Mapping Public and Private Spaces of Urban Agriculture in Chicago through the Analysis of High-Resolution Aerial Images in Google Earth. Lscape Urban Plan. 2012, 108, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, S. Urban Agriculture Impacts: Social, Health, and Economic: A Literature Review; UC SAREP: Davis, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, K.; Cohen, N. Beyond the Kale: Urban Agriculture and Social Justice Activism in New York City; University of Georgia Press: Athens, GA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Santo, R.; Yong, R.; Palmer, A. Collaboration Meets Opportunity: The Baltimore Food Policy Initiative. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2014, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagey, A.; Rice, S.; Flournoy, R. Growing Urban Agriculture: Equitable Strategies and Policies for Improving Access to Healthy Food and Revitalizing Communities; PolicyLink: Oakland, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Alkon, A.H.; Agyeman, J. Cultivating Food Justice: Race, Class, and Sustainability; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Alaimo, K.; Packnett, E.; Miles, R.A.; Kruger, D.J. Fruit and vegetable intake among urban community gardeners. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2008, 40, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmody, D. A Growing City: Detroit’s Rich Tradition of Urban Gardens Plays an Important Role in the City’s Resurgence. Available online: https://urbanland.uli.org/industry-sectors/public-spaces/growing-city-detroits-rich-tradition-urban-gardens-plays-important-role-citys-resurgence/ (accessed on 21 March 2018).

- Daigger, G.T.; Newell, J.P.; Love, N.G.; McClintock, N.; Gardiner, M.; Mohareb, E.; Horst, M.; Blesh, J.; Ramaswami, A. Scaling Up Agriculture in City-Regions to Mitigate FEW System Impacts. In Proceedings of the FEW Workshop: “Scaling Up” Urban Agriculture to Mitigate Food-Energy-Water Impacts, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 5–6 October 2015; pp. 1–68. [Google Scholar]

- Draper, C.; Freedman, D. Review and analysis of the benefits, purposes, and motivations associated with community gardening in the United States. J. Community Pract. 2010, 18, 458–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, M.; Tyman, S.K. Cultivating Food as a Right to the City. Local Environ. 2015, 20, 1132–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovell, S.T. Multifunctional Urban Agriculture for Sustainable Land Use Planning in the United States. Sustainability 2010, 2, 2499–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, T.; Winfree, R. Ecology of Organisms in Urban Environments: Urban drivers of plant-pollinator interactions. Funct. Ecol. 2015, 29, 879–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulak, M.; Graves, A.; Chatterton, J. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions with urban agriculture: A Life Cycle Assessment perspective. Landsc. Urb. Plan. 2016, 111, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santo, R.; Palmer, A.; Kim, B. Vacant Lots to Vibrant Plots: A Review of the Benefits and Limitations of Urban Agriculture; Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Meehan, S. Urban Farm Coming to Former Sparrows Point Steel Mill Site in Baltimore County. Available online: http://www.baltimoresun.com/business/bs-md-sparrows-point-farm-20180508-story.html. (accessed on 10 May 2018).

- McClintock, N.; Cooper, J. Cultivating the Commons: An Assessment of the Potential for Urban Agriculture on Oakland’s Public Land; Portland University Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Algert, S.J.; Baameur, A.; Renvall, M.J. Vegetable Output and Cost Savings of Community Gardens in San Jose, California. J. Acad. Nutr. Die. 2014, 114, 1072–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altieri, M.; Pallud, C.; Arnold, J.; Glettner, C.; Matzen, S. An Agroecological Survey of Urban Farms in the Eastern Bay Area to Explore Their Potential to Enhance Food Security; Research Highlights; Berkeley Food Institute: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2016; Available online: http://food.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Urban-Farms-Web-1.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2018).

- Allen, P. Mining for Justice in the Food System: Perceptions, Practices, and Possibilities. Agric. Hum. Values 2008, 25, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, D. A Survey of Community Gardens in Upstate New York: Implications for Health Promotion and Community Development. Health Place 2000, 6, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, D.; Giesecke, C.C.; Sherman, S. A Dietary, Social and Economic Evaluation of the Philadelphia Urban Gardening Project. J. Nutr. Educ. 1991, 23, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkon, A.; Guthman, J. The New Food Activism: Opposition, Cooperation, and Collective Action; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- McClintock, N. Radical, Reformist, and Garden-Variety Neoliberal: Coming to Terms with Urban Agriculture’s Contradictions. Local Environ. 2014, 19, 147–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClintock, N. Cultivating (a) Sustainability Capital: Urban Agriculture, Ecogentrification, and the Uneven Valorization of Social Reproduction. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2018, 108, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClintock, N. From Industrial Garden to Food Desert: Unearthing the Root Structure of Urban Agriculture in Oakland, California. Cultiv. Food Justice Race Class Sustain. 2011, 89, 90–120. Available online: http://www.web.pdx.edu/~ncm3/files/McClintock_Cultivating_Food_Justice.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2018).

- Anguelovski, I. Healthy Food Stores, Greenlining and Food Gentrification: Contesting New Forms of Privilege, Displacement and Locally Unwanted Land Uses in Racially Mixed Neighborhoods. Int. J. Urban. Reg. Res. 2016, 39, 1209–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, N. Feeding or Starving Gentrification: The Role of Food Policy; CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute. Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/572d0fcc2b8dde9e10ab59d4/t/5aba9936575d1fe8933df34e/1522178358593/Policy-Brief-Feeding-or-Starving-Gentrification-20180327-Final.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2018).

- Voicu, I.; Been, V. The Effect of Community Gardens on Neighboring Property Values. R. Estim. Econ. 2008, 36, 241–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittle, H.J.; Palar, K.; Hufstedler, L.L.; Seligman, H.K.; Frongillo, E.A.; Weiser, S.D. Food Insecurity, Chronic Illness, and Gentrification in the San Francisco Bay Area: An Example of Structural Violence in United States Public Policy. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 143, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sbicca, J. Growing Food Justice by Planting an Anti-Oppression Foundation: Opportunities and Obstacles for a Budding Social Movement. Agric. Hum. Values 2012, 29, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horst, M.; McClintock, N.; Hoey, L. The Intersection of Planning, Urban Agriculture, and Food Justice: A Review of the Literature. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2017, 83, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, M.M. The Elusive Inclusive: Black Food Geographies and Racialized Food Spaces. Antipode 2014, 47, 748–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkon, A.; Mares, T. Food Sovereignty in US Food Movements: Radical Visions and Neoliberal Constraints. Agric. Hum. Values 2012, 29, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, D.R.; Chávez, N.; Allen, E.; Ramirez, D. Food Sovereignty, Urban Food Access, and Food Activism: Contemplating the Connections through Examples from Chicago. Agric. Hum. Values 2012, 29, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, K.; Galt, R.E. Practicing Food Justice at Dig Deep Farms & Produce, East Bay Area, California: Self-Determination as a Guiding Value and Intersections with Foodie Logics. Local Environ. 2014, 19, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brones, A. Karen Washington: It’s Not a Food Desert, It’s Food Apartheid. Available online: https://www.guernicamag.com/karen-washington-its-not-a-food-desert-its-food-apartheid/ (accessed on 11 June 2018).

- Kloppenburg, J.; Hendrickson, J.; Stevenson, G.W. Coming in to the Foodshed. Agric. Hum. Values 1996, 16, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, C.J.; Bills, N.L.; Lembo, A.J.; Wilkins, J.L.; Fick, G.W. Mapping Potential Foodsheds in New York State: A Spatial Model for Evaluating the Capacity to Localize Food Production. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2009, 24, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthman, J.; Morris, A.W.; Allen, P. Squaring Farm Security and Food Security in Two Types of Alternative Food Institutions*. Rural Sociol. 2009, 71, 662–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pensado-Leglise, M.; Smolski, A. An Eco-Egalitarian Solution to the Capitalist Consumer Paradox: Integrating Short Food Chains and Public Market. Syst. Agric. 2017, 7, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handbury, J.; Rahkovsky, I.; Schnell, M. Is the Focus on Food Deserts Fruitless? Retail Access and Food Purchases Across the Socioeconomic Spectrum; Working Paper 21126; NBER: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w21126 (accessed on 25 June 2018).

- Cummins, S.; Macintyre, S. “Food Deserts”—Evidence and Assumption in Health Policy Making. Br. Med. J. 2002, 325, 436–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedore, M. Geographies of Capital Formation and Rescaling: A Historical-geographical Approach to the Food Desert Problem. Can. Geogr. Géogr. Can. 2016, 57, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvez, M.P.; Morland, K.; Raines, C.; Kobil, J.; Siskind, J.; Godbold, J.; Brenner, B. Race and Food Store Availability in an Inner-City Neighbourhood. Public Health Nutr. 2008, 11, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, K.; Gilliland, J. A Farmers’ Market in a Food Desert: Evaluating Impacts on the Price and Availability of Healthy Food. Health Place 2009, 15, 1158–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Qiu, F.; Swallow, B. Can Community Gardens and Farmers’ Markets Relieve Food Desert Problems? A Study of Edmonton, Canada. Appl. Geogr. 2014, 55, 127–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, R.C. Strengthening the Core, Improving Access: Bringing Healthy Food Downtown via a Farmers’ Market Move. Appl. Geogr. 2016, 67, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudzune, K.A.; Welsh, C.; Lane, E.; Chissell, Z.; Anderson Steeves, E.; Gittelsohn, J. Increasing Access to Fresh Produce by Pairing Urban Farms with Corner Stores: A Case Study in a Low-Income Urban Setting. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 2770–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucan, S.C.; Maroko, A.R.; Sanon, O.; Frias, R.; Schechter, C.B. Urban Farmers’ Markets: Accessibility, Offerings, and Produce Variety, Quality, and Price Compared to Nearby Stores. Appetite 2015, 90, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misyak, S.; Ledlie Johnson, M.; McFerren, M.; Serrano, E. Family Nutrition Program Assistants’ Perception of Farmers’ Markets, Alternative Agricultural Practices, and Diet Quality. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2014, 46, 434–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinton, N.; Stuhlmacher, M.; Miles, A.; Uludere Aragon, N.; Wagner, M.; Georgescu, M.; Herwig, C.; Gong, P. A Global Geospatial Ecosystem Services Estimate of Urban Agriculture. Earth’s Future 2018, 6, 40–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galzki, J.; Mulla, D.; Peters, C. Mapping the Potential of Local Food Capacity in Southeastern Minnesota. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parece, T.E.; Serrano, E.L.; Campbell, J.B. Strategically Siting Urban Agriculture: A Socioeconomic Analysis of Roanoke, Virginia. Prof. Geogr. 2017, 69, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, E.A.; Tong, D.; Credit, K. Gardening in the Desert: A Spatial Optimization Approach to Locating Gardens in Rapidly Expanding Urban Environments. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2017, 16, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colasanti, K.J.A.; Hamm, M.W. Assessing the Local Food Supply Capacity of Detroit, Michigan. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2010, 1, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manskar, N. These NYC Farms Are Growing More Than Food. Available online: https://patch.com/new-york/new-york-city/these-nyc-farms-are-growing-more-food (accessed on 24 April 2018).

- McClintock, N.; Mahmoudi, D.; Simpson, M.; Santos, J. Socio-Spatial Differentiation in the Sustainable City: A Mixed-Methods Assessment of Residential Gardens in Metropolitan Portland, Oregon, USA. Landsc. Urban. Plan. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, S. Can Vertical Farms Reap Their Harvest? It’s Anyone’s Bet. Available online: https://civileats.com/2018/07/02/can-vertical-farms-reap-their-harvest-its-anyones-bet/ (accessed on 2 July 2018).

- Despommier, D. The Vertical Farm: Feeding the World in the 21st Century; St. Martin’s Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Alameda County Community Food Bank. Hunger: Alameda County Uncovered. 2014. Available online: https://www.accfb.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/ACCFB-HungerStudy2014-smaller.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2018).

- Kortright, R.; Wakefield, S. Edible Backyards: A Qualitative Study of Household Food Growing and Its Contributions to Food Security. Agric. Hum. Values 2011, 28, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, L.; Guzman, P.; Glowa, K.M.; Drevno, A.G. Can Home Gardens Scale up into Movements for Social Change? The Role of Home Gardens in Providing Food Security and Community Change in San Jose, California. Local Environ. 2014, 19, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algert, S.; Diekmann, L.; Renvall, M.; Gray, L. Community and Home Gardens Increase Vegetable Intake and Food Security of Residents in San Jose, California. Calif. Agric. 2016, 70, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldivar-tanaka, L.; Krasny, M.E. Culturing Community Development, Neighborhood Open Space, and Civic Agriculture: The Case of Latino Community Gardens in New York City. Agric. Hum. Values 2004, 21, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.M.; Kurtz, H. Community Gardens and Politics of Scale in New York City. Geogr. Rev. 2003, 93, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmelzkopf, K. Incommensurability, Land Use, and the Right to Space: Community Gardens in New York City. Urban Geogr. 2002, 23, 323–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, K. Disparity Despite Diversity: Social Injustice in New York City’s Urban Agriculture System. Antipode 2015, 47, 240–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClintock, N.; Cooper, J.; Khandeshi, S. Assessing the Potential Contribution of Vacant Land to Urban Vegetable Production and Consumption in Oakland, California. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 111, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, J.; Rogé, P. Indicators of Land Insecurity for Urban Farms: Institutional Affiliation, Investment, and Location. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daftary-Steel, S.; Herrera, H.; Porter, C. The Unattainable Trifecta of Urban Agriculture. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2015, 6, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biewener, C. Paid Work, Unpaid Work, and Economic Viability in Alternative Food Initiatives: Reflections from Three Boston Urban Agriculture Endeavors. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2016, 6, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, P. Together at the Table: Sustainability and Sustenance in the American Agrifood System; The Pennsylvania State University Press: State College, PA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, Y. Not Just the Price of Food: Challenges of an Urban Agriculture Organization in Engaging Local Residents. Sociol. Inq. 2016, 83, 369–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckie, M.; Fletcher, F.; Whitfield, K.; Bogdan, E. Planting roots: Urban Agriculture for Senior Immigrants. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2010, 1, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, S.; Flint, E.; Matthews, S.A. New Neighborhood Grocery Store Increased Awareness of Food Access but Did Not Alter Dietary Habits or Obesity. Health Aff. 2014, 33, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodier, F.; Durif, F.; Ertz, M. Food Deserts: Is It Only about a Limited Access? Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 1495–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green Bronx Machine–Fuel the Machine. Available online: https://greenbronxmachine.org/ (accessed on 11 June 2018).

- Poe, M.; McLain, R.; Emery, M.; Hurley, P. Urban Forest Just and the Rights to Wild Foods, Medicines, and Materials in the City. Hum. Ecol. 2016, 41, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLain, R.J.; Poe, M.R.; Urgenson, L.S.; Blahna, D.J.; Burrolph, L.P. Urban Non-Timber Forest Products Stewardship Practices among Foragers in Seattle, Washington (USA). Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 28, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackleton, C.; Hurley, P.; Dahlberg, A.; Emergy, M.; Nagendra, H. Urban Foraging: A Ubiquitous Human Practice Overlooked by Urban Planners, Policy, and Research. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kell, G. Foragers Find Bounty of Edibles in Urban Food Deserts. Available online: http://news.berkeley.edu/2014/11/17/urban-foraging/ (accessed on 2 July 2018).

- Stark, P.; Carlson, T. Reaping Without Sowing: Urban Foraging, Sustainability, Nutrition and Social Welfare. Available online: https://food.berkeley.edu/programs/research/seed-grant/reaping-without-sowing/ (accessed on 8 February 2018).

- Ample Harvest. America’s Solution to Food Waste and Hunger. Available online: http://ampleharvest.org/ (accessed on 31 May 2018).

- Curran, C.J.; González, M.-T. Food Justice as Interracial Justice: Urban Farmers, Community Organizations and the Role of Government in Oakland, California. Univ. Miami Inter-Am. Law Rev. 2011, 43, 207–232. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, N. Policy Brief: New Directions for UA in NYC; CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute: Harlem, NY, USA, 2016; Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/572d0fcc2b8dde9e10ab59d4/t/5807af3c9de4bb0ab89dc12e/1476898621115/Policy+Brief-+New+Directions+for+UA+in+NYC.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2018).

- McCracken, V.; Sage, J.; Sage, R. Bridging the Gap: Do Farmers’ Markets Help Alleviate Impacts of Food Deserts? Institute for Research on Poverty: Madison, WI, USA, 2012; Available online: https://www.irp.wisc.edu/wp/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/dp140112.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2018).

- Satterfield, S. Behind the Rise and Fall of Growing Power. Available online: https://civileats.com/2018/03/16/behind-the-rise-and-fall-of-growing-power/ (accessed on 14 March 2018).

- Short, A.; Guthman, J.; Raskin, S. Food Deserts, Oases, or Mirages?: Small Markets and Community Food Security in the San Francisco Bay Area. J. Plan. Edu. Res. 2007, 26, 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- City of Richmond. Urban Agriculture Assessment. Available online: https://www.ci.richmond.ca.us/2530/Urban-Agriculture-Assessment (accessed on 15 May 2018).

- HOPE Collaborative. A Place with No Sidewalks: An Assessment of Food Access, the Built Environment and Local, Sustainable Economic Development in Ecological Micro-Zones in the City of Oakland, California in 2008. Available online: http://www.hopecollaborative.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/hp_aplacewithn-sidewalks.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2018).

- Satterfield, S. Can This Market Be a Model for Getting Good Food into Neighborhoods Shaped by Racism? Available online: http://civileats.com/2016/05/25/can-peoples-community-market-begin-to-undo-a-history-of-structural-racism/ (accessed on 18 February 2018).

- Raja, S.; Ma, C.; Yadav, P. Beyond Food Deserts: Measuring and Mapping Racial Disparities in Neighborhood Food Environments. J. Plan. Edu. Res. 2008, 27, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepeda, L.; Reznickova, A.; Lohr, L. Overcoming Challenges to Effectiveness of Mobile Markets in US Food Deserts. Appetite 2014, 79, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodor, J.N.; Rose, D.; Farley, T.A.; Swalm, C.; Scott, S.K. Neighbourhood Fruit and Vegetable Availability and Consumption: The Role of Small Food Stores in an Urban Environment. Public Health Nutr. 2008, 11, 416–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolen, E.; Hecht, K. Neighborhood Groceries: New Access to Healthy Food in Low-Income Communities; California Food Policy Advocates: Oakland, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gatrell, J.D.; Reid, N.; Ross, P. Local Food Systems, Deserts, and Maps: The Spatial Dynamics and Policy Implications of Food Geography. Appl. Geogr. 2011, 31, 1195–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, S.; Wooten, H. A Food Systems Assessment for Oakland, CA: Toward a Sustainable Food Plan; Mayor’s Office of Sustainability: Oakland, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Alkon, A.H. Black, White and Green: Farmer’s Markets, Race and the Green Economy; Geographies of Justice and Social Transformation; University of Georgia Press: Athens, GA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- GrowNYC’s Greenmarket Program Ensures New Yorkers Have Access to the Freshest, Most Nutritious Locally Grown Food. NYC Food Policy Center. 2018. Available online: http://www.nycfoodpolicy.org/grownycs-greenmarket-program-ensures-new-yorkers-access-freshest-nutritious-locally-grown-food/ (accessed on 2 July 2018).

- SNAP at Farmers’ Markets | Snap to Health. Available online: https://www.snaptohealth.org/snap-innovations/snap-at-farmers-markets/ (accessed on 24 May 2018).

- Chen, S. Civic Agriculture: Towards a Local Food Web for Sustainable Urban Development. APCBEE Proced. 2012, 1, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horst, M.; Gaolach, B. The Potential of Local Food Systems in North America: A Review of Foodshed Analyses. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2015, 30, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D. Reframing Food Hubs: Food Hubs, Racial Equity, and Self-Determination in the South; Race Forward: City, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.raceforward.org/system/files/pdf/reports/RaceForwardCSI_ReframingFoodHubsFullReport_2018.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2018).

- Wallace, H. Suburban “Agrihoods”: Growing Food and Community. Available online: https://civileats.com/2014/07/09/suburban-agrihoods-growing-food-community/ (accessed on 7 June 2018).

- Widener, M.J.; Metcalf, S.S.; Bar-Yam, Y. Developing a Mobile Produce Distribution System for Low-Income Urban Residents in Food Deserts. J. Urb. Health 2012, 89, 733–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weis, T. The Global Food Economy: The Battle for the Future of Farming; Zed Books: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Clendenning, J.; Dressler, W.H.; Richards, C. Food Justice or Food Sovereignty? Understanding the Rise of Urban Food Movements in the USA. Agric. Hum. Values 2016, 33, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.L. Kale, Not Jail: Urban Farming Nonprofit Helps Ex-Cons Re-Enter Society. The New York Times. 18 May 2018. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/17/business/urban-farming-exconvicts-recidivism.html (accessed on 18 May 2018).

- Morales, A. Growing Food and Justice, Dismantling Racism through Sustainable Food Systems. Cultiv. Food Justice Race Class Sustain. 2011, 149, 149–176. Available online: https://cultivatingalternatives.com/2012/10/28/growing-food-and-justice-dismantling-racism-through-sustainable-food-systems-alfonso-morales/ (accessed on 22 August 2018).

- Sussman, M. Will Allen Returns to his Roots. Available online: https://shepherdexpress.com/api/content/3451251a-6e7e-11e8-b34f-12408cbff2b0/ (accessed on 14 June 2018).

- Doherty, M. Detroit “Agrihood” Sparks Discussion on Urban Farming. Available online: https://www.onegreenplanet.org/vegan-food/detroit-agrihood-sparks-discussion-urban-farming/ (accessed on 7 March 2018).

- Pothukuchi, K.; Kaufman, J.L. The Food System: A Stranger to the Planning Field. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2000, 66, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, K. Feeding the City: The Challenge of Urban Food Plan. Int. Plan. Stud. 2009, 14, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, S.S.; Grewal, P.S. Can Cities Become Self-Reliant in Food? Cities 2012, 29, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum-evitts, S. Designing a Foodshed Assessment Model: Guidance for Local and Regional Planners in Understanding Local Farm Capacity in Comparison to Local Food Needs. Masters Theses 1911—February 2014 2009. Available online: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/288 (accessed on 5 July 2018).

- DeDomenica, B.; Gordon, M. Food Policy: Urban Farming as a Supplemental Food Source. J. Soc. Chang. 2016, 8, 1–13. Available online: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com.tw/&httpsredir=1&article=1109&context=jsc (accessed on 22 August 2018).

- Havens, E.; Alcala, A.R. Land for Food Justice? AB 551 and Structural Change; Land and Sovereignty Policy Brief #8; Food First: Oakland, CA, USA, 2016; Available online: https://foodfirst.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/UrbanAgS2016_Final.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2018).

- City of Baltimore. Urban Agriculture Plan (2013). Available online: https://www.baltimoresustainability.org/homegrown-baltimore-plan/ (accessed on 2 July 2018).

- California Community Food Producer Act, AB 1990. (2014). Available online: http://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201320140AB1990 (accessed on 2 July 2018).

- Special Issue: The Food Factor. Available online: https://www.planning.org/planning/2009/aug/ (accessed on 20 May 2018).

- Seattle Department of Neighborhoods. P-Patch Community Gardening. Available online: http://www.seattle.gov/neighborhoods/programs-and-services/p-patch-community-gardening (accessed on 2 July 2018).

- NYC Food Policy. Food Metrics Report 2017. The City of New York; 2017. Available online: https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/foodpolicy/downloads/pdf/2017-Food-Metrics-Report-Corrected.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2018).

- Curran, W.; Hamilton, T. Just Green Enough: Contesting Environmental Gentrification in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. Local Environ. 2012, 17, 1027–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohareb, E.A.; Heller, M.C.; Guthrie, P.M. Cities’ Role in Mitigating United States Food System Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Environ. Tech. 2018, 52, 5545–5554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Born, B.; Purcell, M. Avoiding the Local Trap: Scale and Food Systems in Planning Research. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2006, 26, 195–207. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/2410/c65a10ecef66214181f4971a53294e2adc48.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2018). [CrossRef]

- Bollier, D. Think Like a Commoner: A Short Introduction to the Life of the Commons; New Society Publishers: Gabriola Island, BC, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Posner, E. An Agricultural Movement for People-to-People Reparations Puts Itself on the Map. Rural America in These Times. 2018. Available online: http://inthesetimes.com/rural-america/entry/21140/catatumbo-collective-soul-fire-farm-racial-justice-reparations-agriculture (accessed on 18 May 2018).

- Haletky, N.; Taylor, O. Urban Agriculture as a Solution to Food Insecurity: West Oakland and People’s Grocery. URB. ACTION 2006, 49, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

| Distribution [Related Terms] | Access [Related Terms] |

|---|---|

|

|

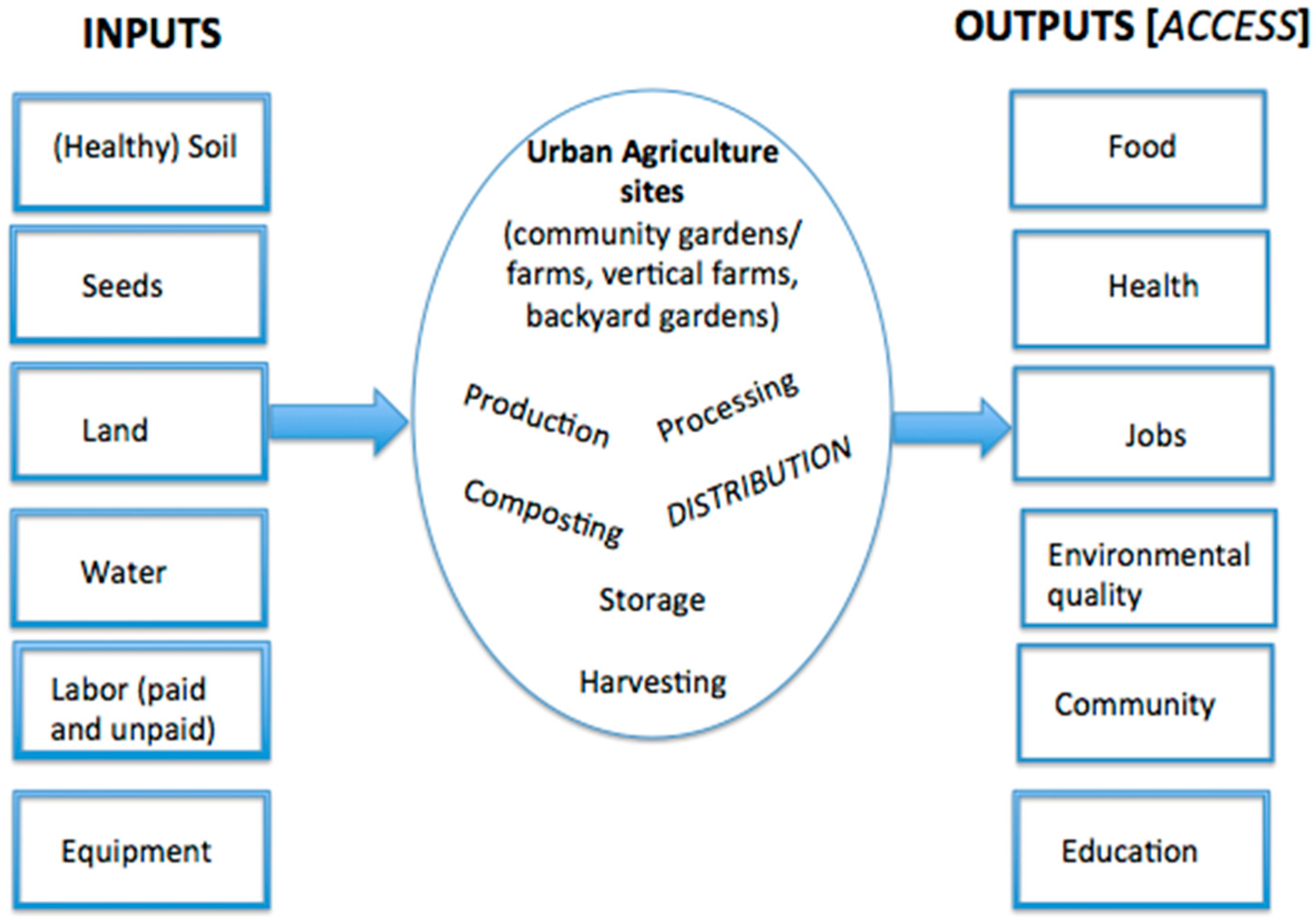

| Basic Food Systems Flowchart: Production → Distribution → Consumption/Access | |

| For Researchers | For Policymakers | For Urban Farmers and UA Participants |

|---|---|---|

| Generate more robust empirical analyses of the impact of urban farms on the commonly cited “multiple benefits,” and particularly on addressing food insecurity. | Secure long-term public land tenure for UA, and ensure it is distributed equitably across class and race | Advocate for justice-oriented UA policy at city council meetings and via local Food Policy Councils |

| Increase research attention on parameters that create food justice outcomes within UA operations (at city, state, and site level) | Revalue UA as a public good and integrate/align with other public funding priorities (including schools, transportation, public health, economic dev. goals, etc.) | Collaborate and partner with other UA sites/networks, and aligned interests across the city (housing, schools, youth and family services, neighborhood organizations, etc.) |

| Consider the production impacts of home gardens as well as larger UA sites (community gardens and commercial operations) when evaluating the potential and actual food contributions of UA | Link UA and housing policy to both provide urban gardens to residents of affordable housing and low-income communities, and prevent displacement via eco-gentrification | Quantify your impact to back up advocacy efforts and increase success in attracting grants/donations |

| Generate more robust analyses of distribution successes & challenges exploring transportation, infrastructure, and investment needs. | Guarantee a “right to food” in your jurisdiction that includes, but is not limited to efforts to incentivize UA | Define a clear focus for your work and stick to a mission, rather than trying to deliver all the benefits of UA at once |

| Map the current landscape of urban ag locations overlaid with neighborhoods experiencing food insecurity and barriers to access in order to identify strategic sites for UA; map distribution channels and food flows as well | Communicate with food policy organizations, food justice advocates, and urban farmers to understand their needs and provide support from city infrastructure | Help set up more home gardens for individuals in order to democratize access to food production |

| Partner with food justice activists and citizen groups working in UA to conduct participatory analyses of on-ground UA realities, including consumption of UA foods. | Promote backyard and home gardens as part of urban food production planning | Places voices of communities of color at the forefront, create space and/or leadership roles for disadvantaged groups within the organizational structure. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Siegner, A.; Sowerwine, J.; Acey, C. Does Urban Agriculture Improve Food Security? Examining the Nexus of Food Access and Distribution of Urban Produced Foods in the United States: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2988. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10092988

Siegner A, Sowerwine J, Acey C. Does Urban Agriculture Improve Food Security? Examining the Nexus of Food Access and Distribution of Urban Produced Foods in the United States: A Systematic Review. Sustainability. 2018; 10(9):2988. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10092988

Chicago/Turabian StyleSiegner, Alana, Jennifer Sowerwine, and Charisma Acey. 2018. "Does Urban Agriculture Improve Food Security? Examining the Nexus of Food Access and Distribution of Urban Produced Foods in the United States: A Systematic Review" Sustainability 10, no. 9: 2988. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10092988

APA StyleSiegner, A., Sowerwine, J., & Acey, C. (2018). Does Urban Agriculture Improve Food Security? Examining the Nexus of Food Access and Distribution of Urban Produced Foods in the United States: A Systematic Review. Sustainability, 10(9), 2988. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10092988