Abstract

In contrast with the existing studies dealing with crisis communication strategies in most aspects of corporates, this study investigated the mechanism of anti-corporate prejudice toward personal-information leakage as part of corporate crisis. This study develops a structural model of anti-corporate prejudice (ACP) in crises, for measuring a perceived crisis (PC), negative emotion (NE) and stereotypes (ST). We used the structural equation model and equality constrained model techniques for testing several proposed hypotheses with experimental research. The results identified the significant positive paths: PC → NE; PC → ST; NE → ACP; ST → ACP. In addition, NE and ST were found to play mediating roles in the relationships between PC and ACP. The mediating effect of NE was seen to have a stronger effect on ACP than ST. Finally, the moderating effect of crisis intentionality (CI) was significant. In particular, for high intentionality focused on internal causes, NE is more likely to increase ACP than ST. On the other hand, for low intentionality focused on external causes, ST is more likely to increase ACP than NE.

1. Introduction

Oxy Reckitt Benckiser (Oxy) claims that their corporate philosophy and goal is to make homes happier through health and hygiene. However, Oxy released a disinfectant for humidifiers and neglected to follow safety verification procedures on their webpage, despite the fact that humidifier disinfectants should to some extent, be expected to be hazardous to humans. This led to the worst chemical disaster in history, causing 239 deaths and 1528 cases of serious lung disease. In fact, unless the damage is serious like Oxy, many incidents inside companies never hit the headlines. Current evidence, however, suggests that more are turning into full-blown corporate crisis. The total amount paid out by corporations on amount of US regulatory infraction has grown by over five rimes, to almost $60 billion per year, from 2010 to 2015. Globally, this number is in excess of $100 billion. Between 2010 and 2017, headlines with the word “crisis” and the name of one of the top 100 companies as listed by Forbes appeared 80% more often than in the previous decade. Most industries have had their casualties. Especially, as the IT environment has changed, pathways of information security in financial environments based on IT have become more diverse and the damage caused by information leakage has become more serious. Among the various types of security incidents that can occur in this context, personal information leakages are liable to inflict the greatest damage to both of companies and customers. The leakage of personally identifiable information is more serious than the problem caused by socio-demographics information leakages. Previous studies on information leakage, however, have only focused on descriptive analysis and detection methods in ICT industry [1,2] and few have considered the issue of information leakage at the strategic level of a corporate crisis. During a crisis, companies often make decisions in terms of how and what to communicate to their stakeholders [3]. In a recent literature review, Coombs [4] identifies factors that affect the choice of organizational crisis response and its influence crisis outcomes. However, much of the existing research on the effects of crisis management focuses on the socio-cognitive process underlying the stakeholders’ perception and evaluation of the organization [5].

In general, unexpected corporate crises not only cause financial damage but also undermine their reputation [5,6] and aggravate the relationship between the company and the customer. Coombs and Holladay [7] classifies crisis types into accidents, transgression, faux pas and terrorism, in accordance with whether the control of the crisis is external or internal and whether the crisis was intentional. More specifically, Coombs [8] categorizes crises into the following: crises where the organization’s responsibility is clearly recognized, in accordance with the strength of the stakeholders’ awareness of the level of responsibility for the crisis (i.e., misdeed of organization, product recalls due to human error and accidents caused by human error); crises where liability is recognized at an intermediate level (i.e., product recalls due to technical defects, accidents caused by technical defects and large-scale damage); and, crises where there is little emphasis on liability (i.e., rumors, natural disasters, malice or product falsification and workplace violence). Not all but most accidents (i.e., personal information leakage) have immediate victims and a company can hardly contradict ethical responsibility for the cause of the accidents. Previous literatures examine the effects of crisis responses (e.g., corporate ability and corporate social responsibility [9] and the impact of crisis response on trust, revenge intention and avoidance intention [10]. These topics have interested in an aspect of a company. Contrastively, this study is emphasized in the aspect of customers for the fact that crisis management relates to a company’s efforts to avert crises before they occur, as well as effective management of crises when they occur [11]. The focal aims of this study are to uncover the effects of psychological response. This research is particularly interested in the formation of anti-corporate prejudice and the effects of perceive crisis, negative emotion and stereotypes on anti-corporate prejudice.

For the formation of anti-corporate prejudice, this study employed the notion of prejudice in the psychological area. Allport [12] defines prejudice as a judgment made about liking or disliking something without experience or knowledge. He illustrated that prejudice has a focal function that allows people who share the same set of preconceived opinions to categorize society and thus create a fixed identity for a minority group of people. Prejudice can, therefore, be called an “unfounded one-sided opinion.” It is formed prior to having sufficient knowledge or experience about a particular group or individual. The characteristics of crisis prejudice are as follows: First, an event that is unrelated to oneself is evaluated on an insufficient and incorrect basis (through interference in the information transfer process, such as exposure through a third party) and is affected by certain prejudices (stereotypes based on past crisis history). Second, prejudice involves a value judgment about the company in crisis. That is, people negatively evaluate the event on the basis of ethical value standards. Third, prejudice is an irrational and emotional attitude. Thus, prejudice shows a strong emotional resistance to rationale and realistic criticism. Prejudice not only refers to a general negative attitude toward an object but also designates a negative evaluation based on the characteristics of a specific object. Prejudice includes belief, emotion and behavior—the three elements of attitude. The aspect of belief refers to a general and abstract knowledge of an object or event as a stereotype. The emotional experiences that are the source of prejudice include negative and hostile feelings about a particular object or event. Finally, the behavioral aspect of prejudice is discrimination, which means that people act in such a way as to disadvantage someone or something, without logical proof, based on specific objects or events. These three aspects of prejudice interact and influence each other. There are other theories of prejudice; for instance, Stangor et al. [13] found that cognition and affect are the determinants of prejudice. Thus, this study reflected their findings and developed perceived crisis, negative emotion and stereotypes as the antecedents of anti-corporate prejudice.

The specific aims of this study include the following. First, this study investigates the relationship among perceived crisis, negative emotion, stereotypes and anti-corporate prejudice. Second, the effect of negative emotion (an emotional aspect) and stereotyping (a cognitive aspect) is tested between perceived crisis and anti-corporate prejudice by using Baron and Kenny’s method [14], the results of being analyzed to verified the role of negative emotion and stereotyping toward crisis as mediators. Third, the moderating effect of crisis intentionality was considered to describe this structural model which anti-corporate prejudice is able to be greatly increased from negative emotion or stereotypes at the moment people perceive the crisis.

This study suggests several contributions to literature as well as management practice: (1) the results extend existing research on crisis response. It shows that the mechanism of the perception of crisis response into individuals’ psychological status is the formation of anti-corporate prejudice. (2) In terms of sustainability, this study provides practical implications on how to properly adjust negative emotion and stereotypes to reduce anti-corporate prejudice for overcoming the critical incidents in at the moment of a crisis situation and before a crisis happen.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis

2.1. The Effect of Perceived Crisis on Negative Emotion and Stereotypes

When a crisis occurs, the public tends to believe that there is a problem in the company involved. Given the fact that this can have a negative effect on the interaction between the company and the customer, as well as on the reputation of the company, crisis communication strategies have become important for protecting their reputation [6,15]. Moreover, as the information of a crisis reduces the brand’s equity (such as its sales, credibility and image) it weakens the effectiveness of marketing activities and makes the brand vulnerable to a competitor’s attack. In addition, it has a negative effect on brand attitude and purchase intention [16,17]. Furthermore, a brand crisis can even affect other associated brands and product groups [18,19,20,21,22]. As a crisis tends to occur suddenly, it is usually surprising and threatening, allowing little time to respond. Consequently, we need to understand that the highly disturbing, threatening and urgent nature of crises leaves a company no choice. Furthermore, a crisis accompanied by a high degree of uncertainty is an unexpected and non-routine event that threatens a company’s goals [23]. During a crisis, previous researches on the relationship between emotion and judgment or decision-making have been examined [24] because emotions are the important cues in the cognitive information processing such as decision-making, judgment and evaluation [25]. In particular, emotions become an indicator to understand behavior in specific situations. For example, a crisis situation evokes many kinds of emotions such as compassion, relief, anger, fear and displeasure [26]. Of these, anger is most commonly associated with the crisis and has the impacts on not only the relationship between companies and customers but also customer defection [27]. Contrary to anger, sympathy has a positive impact on the company [24,27]. According to Coombs and Holladay [26], stockholders are even angrier after perceiving the higher degree of risk responsibility the crisis. Jin, Pang and Cameron [28], who examined the emotion variable in crisis communications, sought to conceptualize crisis communications on the basis of the public’s emotional response. They developed an ‘integrated crisis mapping model’ by organizing the public’s emotional responses by crisis type into two axes: organizational engagement and coping strategies. Meanwhile, Kim and Cameron [29] explored the role of emotion, including anger and sadness, in crisis communications.

Jin, Pang and Cameron [28], who examined the emotion variable in crisis communications, sought to conceptualize crisis communications on the basis of the public’s emotional response. They developed an ‘integrated crisis mapping model’ by organizing the public’s emotional responses by crisis type into two axes: organizational engagement and coping strategies. Meanwhile, Kim and Cameron [30] explored the role of emotion, including anger and sadness, in crisis communications. In these studies, the group that read crisis news that aroused anger was reported to have a more negative attitude towards the company involved in the crisis than the group that read news that induced sadness. The public’s response and crisis communication strategies varied according to the emotion they experienced.

Studies of categorization processing are usually conducted in the context of intergroup relationships, unlike studies on the detailed information processing of a stereotype. When observing others, people often identify the category to which they belong, and, based on this category, form an impression and make key judgments of others. The categorized target may therefore be remembered and judged in a distorted way using prior knowledge of that category (i.e., using a stereotype). Therefore, the categorization of a group requires category dimensions by which people are divided into majorities and minorities. Moreover, a brand crisis has a negative effect on brand attitude, purchase intention and other properties not previously mentioned [17,18], because it jeopardizes the brand’s equity and the effectiveness of marketing activities. In addition, brand crisis even affects other associated brands and product groups [18,19]. As mentioned above, we could predict that the perception of a crisis has an impact on company image as negative stereotypes.

Accordingly, the following hypothesis is established:

Hypothesis 1.

A perceived crisis will have an effect on negative emotion (a) and stereotypes (b).

2.2. The Mechanism of Anti-Corporate Prejudice in a Crisis

Prejudice corresponds to cognitive beliefs, affects and discriminatory behaviors towards members of a group on account of their membership to this group [30]. Frequently, prejudices refer to negative feelings associated to a particular group [31] and stereotype is their cognitive component.

Emotional side of prejudice and is based on the positive and negative characteristic that a person with prejudice experiences when encountering or thinking about a member of a specific group. However, in many cases, prejudice is based on an unfavorable affect toward the group to which the target belongs [18]. Direct evidence for this reaction has been revealed in various studies designed to measure the emotional response to members of one’s own racial group versus to members of a different racial group. The judgment of an individual differs according to how the individual is categorized (i.e., which group the individual belongs to). Prejudice was operationalized as negative affect elicited by members of the target immigrant group. Negative affect is a fundamental component of prejudice and the use of affective measures of prejudice has ample precedent in the literature [32].

On the other hand, stereotyping refers to the cognitive aspect of prejudice. Stereotyping exercises a powerful influence on how people process information. For example, information associated with a specific stereotype is processed faster than information that is not. Likewise, people with stereotypes concentrate on a specific form of information, often an input that matches the stereotype. On the contrary, when information that is inconsistent with a particular stereotype enters into consciousness, the information is rejected with reference to the information that matches the stereotype. From this perspective, prejudice results in an out-group—a group to which one does not belong—being seen as more heterogeneous than an in-group—a group to which one belongs. This phenomenon is likely to result in discriminatory attitudes and behavior. According to group norm theory [33], which states that a personal belief system is mostly based on social norms, a crisis event will cause negative prejudice by acting as a prescribed value by which to evaluate the organization.

Jussim, Nelson, Manis and Soffin [34] found that affect could predict discriminatory behavior more accurately than stereotyping because affect is evoked from the direct experience of interacting with people in the group, whereas stereotypes are formed by indirect experience (i.e., word of mouth). Generally, people may be prejudiced toward a particular member of a minority group on the basis of negative or positive cues but prejudice is more often formed on the basis of positive or negative emotions toward the whole group rather than a specific person. The emotional aspect of prejudice has provided direct evidence of this tendency. Previous studies designed to measure the emotional response to an ethnic group revealed that the judgment of an individual differs according to how the individual is categorized (the group to which the individual belongs). These studies show, in particular, that the perceiver’s emotional reaction to an individual is influenced by the extent to which the individual is seen as having the characteristics of the group: that is, emotional factors are more influential than the beliefs of the perceiver. Studies of categorization processing are usually carried out in the context of intergroup relationships, unlike studies on the detailed information processing of a stereotype. When observing others, people often identify the category to which they belong. On the basis of this category, they form an impression of others and also make key judgments about them. The categorized target may therefore be remembered and judged in a distorted way using prior knowledge for that category (i.e., using a stereotype). The categorization of a group requires category dimensions by which people are divided into majorities and minorities.

In the studies discussed above, the belief aspect is referred to as stereotyping and reflects general and abstract knowledge about the characteristics of people who belong to a particular group. The emotional source of prejudice refers to the negative or hostile emotions towards the people in a particular group. Stereotyping, which corresponds to the cognitive aspect of prejudice, exercises a powerful influence on the way processing information. For example, the information associated with a specific stereotype is processed faster than the general information. Likewise, when people rely on stereotypes, they tend to focus on specific information that matches the stereotype. On the other hand, when information that is inconsistent with a particular stereotype enters into the consciousness, that information tends to be rejected in favor of information that matches the stereotype. Thus, the structure of prejudice is not single-dimension but multi-dimension separated from the cognitive and emotional aspects. At this point, we could expect that negative emotion and stereotypes of cognition-driven are antecedent variables of prejudice.

Based on existing researches [30,31,32], the concept of anti-corporate prejudice was defined the negative bias formed by negative feelings about a corporate crisis and the information withdrawn from memory (e.g., negative business information, scandals, rumors, etc.). Furthermore, to better measure the biased attitudes to the corporate crisis, this study employed the concept of prejudice with negative emotion and stereotypes.

Accordingly, this study established the following hypothesis for the impact of negative emotion and stereotyping on anti-corporate prejudice:

Hypothesis 2.

Negative emotion (a) and stereotypes (b) will have a positive effect on anti-corporate prejudice.

2.3. The Moderating Effect of Crisis Intentionality

Coombs [35] claimed that when the repeatability of a crisis is high, external control is weak while internal control is strong and if the cause of the crisis is from within the organization, accountability for the crisis increases. As the discussion of crisis accountability has expanded to the perception of severity, Benoit [36] regards severity, normativity and responsibility as three variables that affect the recovery strategy. If one feels a strong sense of responsibility for the situation, one may be negative about the possibility of recovery. As severity increases, long-term recovery may be perceived as unlikely. That is, responsibility and severity can have an effect on the perception of recovery potential and ultimately on purchase intention.

According to the defensive–attribution hypothesis, people feel uncomfortable and fearful when a serious problem occurs and therefore blame other individuals or organizations in order to avoid these feelings [37,38]. Ultimately, the defensive attribution theory suggests that the identification of intentionality may significantly increase the severity of the event. The fact that the relationship between a perceived crisis and prejudice affects the accommodative mediating effect of negative emotion by intentionality can be explained through the defensive attribution hypothesis.

Kruglanski [39] presented “cognitive closure motivation” as an important cognitive tactic that people use for information processing. Cognitive closure motivation can differ between individuals and in response to situational pressures. If motivation increases, people are more likely to process information on the basis of knowledge such as stereotypes, rather than using sophisticated information processing or actively accepting new information.

The psychological factors related to perceived crises (negative emotion and stereotypes) that are formed by consumers are expected to represent the different effects caused by different levels of intentionality. For example, consumers negatively perceive an organization when a high level of intentionality is observed. In this case, negative emotions will have a greater impact than stereotypes on prejudice toward the organization. On the other hand, in the case of a low level of intentionality, cognitive closure motivation—which considers the crisis similar to an event in the past—will be ignited and thus prejudice will be formed by stereotypes rather than by negative emotions. Accordingly, we established the following hypothesis in order to verify the different effects of negative emotion and stereotypes on anti-corporate prejudice, depending on the crisis intentionality level:

Hypothesis 3.

The mediating effect of negative emotion and stereotypes will be moderated by crisis intentionality in the relationship between a perceived crisis and anti-corporate prejudice.

Hypothesis 3a.

In the relationship between a perceived crisis and anti-corporate prejudice, the mediating effect of stereotypes will be stronger for a group with a high level of intentionality than for a group with low intentionality.

Hypothesis 3b.

In the relationship between a perceived crisis and anti-corporate prejudice, the mediating effect of negative emotions will be stronger for a group with a low level of intentionality than for a group with high intentionality.

3. Methodology

We applied a scenario-based experimental design as the research method and data were collected through questionnaires. Participants (N = 129/male = 49.6%; female = 50.4/mean age = 23.4) were undergraduate students and were divided into two groups: 65 in the high intentionality group and 64 in the low intentionality group.

3.1. Stimulus Development

In this study, an experiment was created regarding the infringement of the personal information of users of REAL-Net, a fictitious company in the Internet industry. A scenario was created where all personal data had been released as a result of a hacking incident and the victims had sued REAL-Net. The participants were divided into two groups—high and low intentionality—and their level of intentionality was manipulated by indicating the cause of the crisis event as arising from either internal or external factors. In the scenario of a high level of intentionality, it was indicated that REAL-Net’s crisis happened mainly as a result of careless internal management of personal information. Stimuli were created in the form of an online newspaper with realistic components, article lengths and headlines, adjusting for equivalence in the two groups.

Participants were randomly assigned to the two groups. Questionnaires were distributed, consisting of three sections. First, participants were asked to identify the seriousness of frequent personal information leaks as a social problem that has emerged in recent years; this was done before presenting the stimuli. Second, manipulation of the fictitious scenario was verified through measurement of the level of intentionality. Finally, participants were questioned on their brand awareness, their attitude toward the brand of REAL-Net, the perceived crisis, negative emotion, stereotyping and prejudice. Demographic information was also collected. At the end of the study, all participants were debriefed and thanked for their participation.

The measures of the level of intentionality showed that participants who were exposed to the crisis message where the cause was presented as internal identified REAL-Net as having 79.4% intentionality, while those who were exposed to the message that the cause was external identified a level of intentionality of 62.2%. A manipulation check indicated that a high level of intentionality (M = 3.97, SD = 1.274) was significantly higher than a low level of intentionality (M = 3.11, SD = 1.100), indicating that the manipulation was successful.

3.2. Measurements

Perceived corporate crisis: Crisis has an influence on the formation of perceived risk as well as corporate image, reputation, or purchase. In this study, perceived crisis defines the degree to which the crisis posed a problem for the company; respondents rated the scenario using four items [40].

Negative emotions: Emotions are defined as the complicated and simultaneous reactions to an environmental stimulation with emotional consciousness, emotional feeling, attitude and behavior [41]. Negative crisis emotions examined by researchers include alarm, contempt, disgust, confusion, apprehension, embarrassment, guilt, surprise and shame [24,42], based on the discrete emotions identified by social psychologists [43]. Based on previous research, four items were measured.

Stereotypes: Stereotyping has been referred to the basic cognition at the initial stage of information process, thereby being categorization [44,45], illusory correlation [46] and generalization [47]. For the definition of stereotype on crisis, we employed Rothnart [48] mentioned the notion of ethical norms’ value. Thus, stereotype on crisis was measured with five items.

Anti-corporate prejudice: Prejudice is defined as “predispositions” to adopt a negative behavior toward a group, predispositions based on erroneous generalizations with no consideration to individual differences [12]. This study focused on behavioral intention and behavior of prejudice in order to distinguishing it from negative affect and stereotype. Anti-corporate prejudice was measured by three items. For all measurements were used on a seven-point Likert-type scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (7) (see Table A1 in Appendix A).

3.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

The measurement scales and fit statistics are shown in Table 1. The conceptual model yields χ2 of 281.263, df = 95 and p = 0.000 indicating that the model fits the data very well. However, because χ2 statistic is very sensitive to the sample size it is more appropriate to look at other fit measures. Fortunately, other fit measures also indicate the goodness of fit of the model to the data (CMIN/df = 1.96, CFI = 0.907, IFI = 0.909, GFI = 0.853 and RMSEA = 0.086).

Table 1.

The results of confirmatory factor analysis for the measure.

The convergent validity of variables was assessed based on the factor loadings, composite reliabilities (CR) and average variances extracted (AVE). As shown in Table 1, the factor loadings of all items exceeded the recommended level of 0.50 except for two items (negative emotion 4 = 0.416, anti-corporate prejudice 3 = 0.446). The removal of unsatisfied items is not necessary but this indicates that they have less impact on our model fit. All t-values corresponding to the pathways between the scales and their respective factors were statistically significant at the 0.01 level. The CR, which depicts the degree to which the construct indicators indicate the latent construct, exceeded the recommended level of 0.7. All these figures show that the convergent validity of the variables is acceptable.

A construct should share more variance within its measures than it shares with other constructs in the model [49]. In other words, the average variance extracted (AVE) should exceed the square of the correlation coefficient of the construct [50]. None of the squares of correlation coefficients for the constructs exceeded the AVE for the constructs. Consequently, all constructs exhibited satisfactory discriminant validity (see Table 2).

Table 2.

The squared correlations and AVE of the constructs.

4. Results

4.1. The Effect of Perceived Crisis on Negative Emotion, Stereotyping and Anti-Corporate Prejudice

Significance results of the hypothesis as follows (see Table 3): First, a perceived crisis could affect negative emotions and stereotypes. The analysis showed that the effect of the perceived crisis on negative emotions (t = 3.372, p < 0.01) and stereotypes (t = 3.430, p < 0.01) was significantly positive in both cases. This supports the argument of Coombs and Holladay [51] that a crisis event causes consumers to experience emotions (especially negative emotions) and that negative stereotypes are caused by crisis messages because of the declining receptive capacity of cognition. Second, we predicted that negative emotion and stereotypes would have an impact on prejudice. As anticipated, anti-corporate prejudice was influenced positively by negative emotions (t = 3.959, p < 0.01) and stereotypes (t = 4.964, p < 0.01). This confirmed the results obtained by Jussim et al. [34], who stated that anti-corporate prejudice is formed from a cognitive and emotional source. Thus, H1 and H2 were supported.

Table 3.

Results of pathway analysis.

4.2. The Mediating Effect of Negative Emotion and Stereotypes

The mediating effect of negative emotion and stereotypes were tested by employing Baron and Kenny’s [14] method, which explains the relationship between an independent variable and dependent variable when they meet the following conditions; (1) the independent variable influences significantly the mediating variable, (2) mediating variable influences significantly dependent variable, (3) when path 1 and 2 are controlled, a previously significant relationship between the independent and dependent variable is not significant. As seen in Table 4, positive and significant indirect effect of a perceived crisis on prejudice via negative emotion and stereotyping, with 95% confidence intervals and 1000 bootstrap resembles for assigning measures of accuracy. The direct effect was not significant (b = 0.000, p > 0.05) but the total effect of a perceived crisis on anti-corporate prejudice via negative emotion and stereotyping were significant, b = 0.349 (p < 0.01). We assumed that negative emotion and stereotyping between a perceived crisis and prejudice had an effect of full mediation.

Table 4.

Direct and indirect effects.

4.3. The Moderating Effect of Crisis Intentionality

Prior to testing the moderating effects, we decided to propose the alternative model by adding two pathways: perceived crisis → anti-corporate prejudice, negative emotion → stereotype, for improving our conceptual model. Bodenhausen [52] proposed that mood can affect stereotypical information processing and further stated that the effect of mood on the processing of personal information can be viewed as a process that occurs as a function of mood, affect, arousal and cognitive motivation. Their research shows that negative emotions, including anger, fear and anxiety, reduce cognitive capacity by increasing arousal; they cause people to be more reliant on stereotypes as heuristics. The alternative model was better satisfied according to the goodness of fit index (GFI) than the conceptual model in Table 5: Δχ2(df = 2) = 23.388, p < 0.01

Table 5.

Conceptual Model versus Alternative Model.

Finally, we ran a moderation analysis to investigate the conceptual model depending on the level of CI (high level of intentionality and low level of intentionality). In particular, we proposed that CI played the moderating role in the relationship between a perceived crisis and anti-corporate prejudice based on Raykov’s logic [53], which stated that constraining for equality across groups of some of those parameters where the models differ can yield nonequivalent multiple-group models. With the cross-group equality restriction upon the structural regression path, two nonequivalent models with distinct fit indices were obtained: for the unconstrained model this was χ2(86) = 357.585; and for the constrained model it was χ2(80) = 375.698. To evaluate these differences statistically, chi-square difference tests of the two groups were conducted. That is, statistical differentiation (Δχ2(6) = 11.490) of the two-group models was significant, with 95% confidence intervals in the χ2-distribution (see Table 6).

Table 6.

The results of group equality constraints.

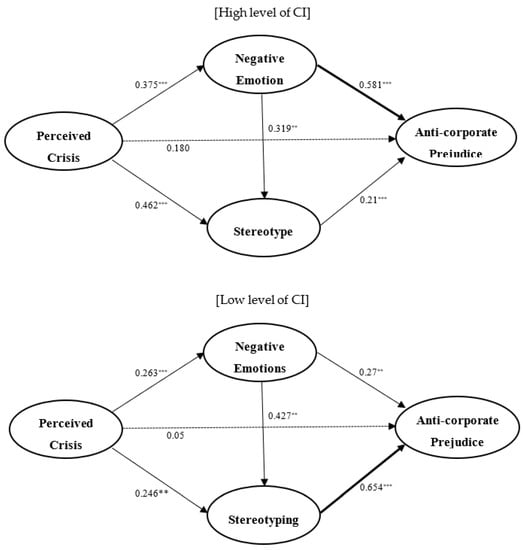

Figure 1 shows the difference between the structural models given a high and low level of intentionality. The results showed that the restrictions of equal coefficients were accepted in two pathways; negative emotion → anti-corporate prejudice (Δχ2(1) = 9.301, p = 0.003) with α = 5% and stereotype → anti-corporate prejudice (Δχ2(1) = 3.519, p = 0.061) with α = 10%. Furthermore, the impact of negative emotion on anti-corporate prejudice was relatively stronger with a high intentionality than with a low intentionality, while the impact of stereotyping on anti-corporate prejudice was higher with low than with high intentionality. Therefore, H3a and H3b were supported.

Figure 1.

Pathway analysis between the two groups. Solid arrows represent significant paths; dotted arrows represent paths that wan not significant; bold arrows represent a significant difference between two groups. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05.

The results of the analysis that examined the differences between the groups by using a structured weight model by level of CI are discussed here. First, regarding the structural model for the effect of negative emotion and stereotype on anti-corporate prejudice, the difference between intentionality levels was verified. Second, the comparison analysis of each pathway between the high and the low intentionality group showed that negative emotion was found to have a stronger effect on anti-corporate prejudice than stereotyping for high intentionality. Anti-corporate prejudice of the group with low intentionality was formed based on stereotyping rather than negative emotion. Third, intentionality’s mediated role, which controls the effect of negative emotion and stereotyping on anti-corporate prejudice, was identified as a moderator. Although a corporate crisis itself does not have a direct impact on the formation of anti-corporate prejudice, negative emotion and stereotypes act as a platform for crisis situations and thus, influence negative prejudice. At this time, negative emotion and stereotyping have an indirect effect on the relationship between a perceived crisis and anti-corporate prejudice, and, at the same time, a regulative mediating effect by CI level.

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary of Results and Discussion

This study explored the psychological structure of a crisis, which consists of negative emotion, stereotyping and anti-corporate prejudice. Even though this is an important area of study, previous research on crisis management and crisis communication strategies has yet to adequately address this. A theoretical hypothesis was composed and analyzed using a structural equation model as the research model. The moderating effect of crisis intentionality was validated through multi-group analysis. The summarized results are as follows: First, a perceived crisis—has an impact on negative emotions and stereotypes. For the purpose of understanding the communication between organization and public, Jin et al. [28] found that that four of the six negative emotions (anger, fright, anxiety and sadness) tend to be dominant emotions experienced by publics in organizational crisis situations. The function of stereotype is to simplify and systematize received stimuli in order to ease cognitive and behavioral adaptation in a new situation of communication [54]. As in the previous research, a crisis evoked negative emotion among the stakeholders.

Second, negative emotion and stereotyping for a crisis were found to increase anti-corporate prejudice. Coombs and Holladay [55], who stressed the importance of understanding the public’s emotional response in a crisis situation, included the concept of emotion in situational crisis communication theory. Many previous studies that have reviewed crisis management strategies have found a relationship between crisis and affect and that affect has an effect on a company’s reputation and behavioral intention [24,28,29,55,56,57]. The results of our study are consistent with these previous findings. Thus, negative emotion needs to be understood as a key factor in the formation of anti-corporate prejudice towards a company and there is a need to examine negative emotion resulting from specific incidents, including the type and strength of affect (arousal), when considering anti-corporate prejudice reduction strategies.

Stereotyping, defined as existing knowledge about a target group, simplifies information on the basis of an existing framework. Accordingly, it evokes automated thinking about the behavior of the target, causes people to immediately pay attention and aids interpretation. However, as this study has confirmed, an effect of stereotyping is often to increase negative prejudice. This reconfirms the opinion of previous researchers that, while stereotyping simplifies information processing and makes it more efficient [30,31], it can also introduce error and bias.

Third, in order to improve the existing research model, an alternative model was proposed, which adds a pathway for the influence of negative emotion on stereotyping. As a result, a positive relationship between negative emotion and stereotyping was validated. This is consistent with the results of a previous study that found that positive emotion or negative emotion both reduced cognitive capacity or cognitive motivation by causing arousal [52]. In particular, Bodenhausen, Sheppard and Kramer [58] stated that, since at some levels of grief arousal does not result, stereotypical information processing does not often occur. However, anger increases the effect of stereotyping, making a negative stereotype of a company in crisis more likely to emerge when people experience anger in response to the crisis.

Fourth, crisis intentionality was found to have a moderating role in how negative emotions and stereotypes impact on anti-corporate prejudice. Specifically, in the group with high intentionality, negative emotion had a relatively greater effect on anti-corporate prejudice than stereotyping; on the other hand, in the group with low intentionality, stereotypes had a greater effect than negative emotion on increasing anti-corporate prejudice.

According to attribution theory [59], when an unexpected situation such as a crisis or negative event occurs, people tend to find a cause for the situation and assess liability according to the cause. When the cause of the incident is internal to the organization, the public tends to hold the company responsible. In this attribution process, anger occurs [60]. On the contrary, when responsibility is attributed to causes outside of the organization, sympathy for the company may occur [61]. This clearly explains the phenomenon whereby the strongest influence of negative emotion occurred in the group with high intentionality.

Recently, corporate sustainability is emphasized because sustainability helps the continuous growth of the corporation into three aspects: environment, social and economy. Especially, the environmental and social aspects art focused on business ethics. In terms of corporate sustainability, this study provides corporates should endeavor to reduce anti-corporate prejudice by adjusting negative emotion and stereotypes as for coping with unexpected and harmful crises.

5.2. Limitations

Despite the interesting theoretical and practical implications discussed above, this study was subject to some limitations.

First, this study did not consider the status and type of intentionality. For practical reasons, when intentionality arose from internal factors, it was classified into the group with high intentionality. When it came from external factors, it was classified into the group with low intentionality. However, there is a possibility that the interaction between a perceived crisis and corporate intentionality had a negative effect on the net direct effect of a perceived crisis due to manipulation.

The second limitation is in regard to the manipulation of the intentionality level. As the manipulation of the level of intentionality was found to be statistically significant in this study, it was regarded as successful. However, the problems that cause a brand crisis in reality can be more severe than the kinds of stimulus presented in the experiments. Accordingly, research needs to be conducted wherein the intentionality levels are manipulated to be as similar to authentic situations as possible.

Third, regarding the demographic characteristics of the subjects, the ages and occupational groups were limited as the sample was composed entirely of male and female university students in their early 20s. In addition, despite the fact that a crisis can further facilitate stereotypic processing for subjects who have extensive prior knowledge about crisis messages and information through media or SNS (Social Network Service), this study did not address individual variables that could affect this process. Accordingly, the effect of individual characteristics needs to be explored in future research.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Changshin University Research Found of 2017 (No. Changshin 2017-001).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Summary of Multi-Items.

Table A1.

Summary of Multi-Items.

| Constructs | Items |

|---|---|

| Perceived crisis | - This crisis event leads to a serious economic threat of the company. - This crisis event has a negative impact on the company’s reputation. - These circumstances caused by the crisis are out of control. - It is very difficult for the company decision making to solve these problems. |

| Negative emotion | - Anger - Annoyance - Blame - Anxiety |

| Stereotypes | - I do not trust the company experienced crisis. - I devaluate the company experienced crisis. - I regard the company experienced crisis as a failure. - I think the company experienced crisis is against the law. - I do not think that the company experienced crisis can resume business. |

| Anti-corporate prejudice | - I think the company has been operating under unethical conditions. - I cannot tolerate the crisis of the company as a general social problem. - I think that the performance achieved by the company is not desirable. |

References

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Yan, Q.; Deng, R.H. Privacy leakage analysis in online social networks. Comput. Secur. 2015, 49, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Sung, W.; Choi, C.; Kim, P. Personal information leakage detection method using the inference-based access control model on the Android platform. Pervasive Mob. Comput. 2015, 24, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufer, D. Emerging issues in crisis management. Bus. Horiz. 2015, 58, 137–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, W.T. How publics react to crisis communication efforts: Comparing crisis response reactions across sub-arenas. J. Commun. Manag. 2014, 18, 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundy, J.; Pfarrer, M. A burden of responsibility: The role of social approval at the onset of a crisis. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2015, 40, 345–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, W.T. Protecting organization reputations during a crisis: The development and application of situational crisis communication theory. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2007, 10, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, W.T.; Holladay, S.J. Communication and attributions in a crisis: An experimental study of crisis communication. J. Public Relat. Res. 1996, 8, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, W.T. Crisis management: A communicative approach. In Public Relations Theory, 2nd ed.; Botan, C.H., Hazleton, V., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 171–197. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Kim, H.J.; Cameron, G.T. Making nice may not matter: The interplay of crisis type, response type and crisis issue on perceived organizational responsibility. Public Relat. Rev. 2008, 38, 86–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, M.; Freidank, J.; Wannow, S.; Cavallone, M. Effect of perceived crisis response on consumers’ behavioral intentions during a company scandal—An intercultural perspective. J. Int. Manag. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peatson, C.; Clair, J. Reframing crisis management. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allport, G.A. The Nature of Prejudice; Addison-Wesley: Oxford, UK, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Stangor, C.; Sullivan, L.A.; Ford, T.E. Affective and cognitive determinates of prejudice. Soc. Cogn. 1991, 9, 359–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichart, J. A theoretical exploration of expectational gaps in the corporate issue construct. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2003, 6, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahluwalia, R.; Unnava, H.R.; Burnkrant, R.E. The moderating role of commitment on the spillover effect of marketing communications. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 458–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawar, N.; Pillutla, M.M. Impact of product-harm crises on brand equity: The moderating role of consumer expectations. J. Mark. Res. 2000, 37, 215–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlen, M.; Fredrik, L. A disaster is contagious: How a brand in crisis affects other brands. J. Advert. Res. 2006, 46, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Dawar, N.; Lemmink, J. Negative spillover in brand portfolios: Exploring the antecedents of asymmetric effects. J. Mark. 2008, 72, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehm, M.L.; Tybout, A.M. When will a brand scandal spill over, and how should competitors respond. J. Mark. Res. 2006, 43, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, M. Measuring image spill-over in umbrella-branded products. J. Bus. 1990, 63, 309–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Heerde, H.; Helsen, K.; Dekimpe, M.G. The impact of a product-harm crisis on marketing effectiveness. Mark. Sci. 2007, 26, 230–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulmer, R.R.; Sellnow, T.L.; Seeger, M.W. Effective Crisis Communication: Moving from Crisis to Opportunity; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y.; Lin, Y.-H. Consumer response to crisis: Exploring the concept of involvement in Mattel product recalls. Public Relat. Rev. 2009, 35, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, N.; Clore, G.L. Mood, misattribution, and judgments of well-being: Informative and directive functions of affective states. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 48, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, W.T.; Holladay, S.J. The negative communication dynamic: Exploring the impact of stakeholder affect on behavioral intentions. J. Commun. Manag. 2007, 11, 300–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, B.K. Components of consumer reaction to company-related mishaps: A structural equation model approach. Adv. Consum. Res. 1996, 23, 346–351. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Y.; Pang, A.; Cameron, G.T. Toward a public-driven, emotion based conceptualization. J. Public Relat. Res. 2012, 24, 266–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Cameron, G.T. Emotions matter in crisis the role of anger and sadness in the publics’ response to crisis news framing and corporate crisis response. Commun. Res. 2011, 38, 826–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyens, J. Prejudice in society. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences; Smelser, N., Baltes, P., Eds.; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 11986–11989. [Google Scholar]

- Ruscher, J. Prejudiced Communication: A Social Psychological Perspective; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pehrson, S.; Brown, R.; Zagefka, H. When does national identification lead to the rejection of immigrants? Cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence for the role of essentialist in-group definitions. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 48, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherif, M.; Sherif, C.W. Groups in Harmony and Tension: An Integration of Studies of Intergroup Relations; Harper and Brothers: Oxford, UK, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Jussim, L.; Nelson, T.E.; Manis, M.; Soffin, S. Prejudice, stereotypes and labeling effects: Sources of bias. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 68, 228–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, W.T. Impact of past crises on current crisis communication: Insights from situational crisis communication theory. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2004, 41, 265–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, W.L. Image repair discourse and crisis communication. Public Relat. Rev. 1997, 23, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, J.M. Motivational biases in the attribution of responsibility for an accident: A meta-analysis of the defensive-attribution hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1981, 90, 496–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbennolt, J.K. Outcome severity and judgments of responsibility: A meta-analytic review. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 30, 2575–2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruglanski, A.W. Motivations for judging and knowing: Implications for causal attribution. In Handbook of Motivation and Cognition; Higgins, E.T., Sorrentino, R.M., Eds.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 333–367. [Google Scholar]

- Arpan, L.M. When in Rome? The effects of spokesperson ethnicity on audience evaluation of crisis communication. J. Bus. Commun. 2002, 39, 314–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plutchik, R. Emotion: A Psych Evolutionary Synthesis; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.F.; Austin, L.; Jin, Y. How publics respond to crisis communication strategies: The interplay of information form and source. Public Relat. Rev. 2011, 37, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frijda, N.H.; Kuipers, P.; Schure, E. Relations among emotion, appraisal, and emotional action readiness. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 212–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H. Cognitive aspects of prejudice. J. Soc. Issues 1969, 25, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.E. A categorization approach to stereotyping. In Cognitive Processes in Stereotyping and Intergroup Behavior; Hamilton, D.L., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, D.L. (Ed.) Illusory correlation as a basis for stereotyping. In Cognitive Processes in Stereotyping and Intergroup Behavior; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Quattrone, G.A.; Jones, E.E. The perception of variability within in-groups and out-groups: Implications for the law of small numbers. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 38, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothbart, M. Memory processes and social beliefs. In Cognitive Processes in Stereotyping and Intergroup Behavior; Hamilton, D.L., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis: With Readings; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, W.T.; Holladay, S.J. Helping crisis managers protect reputational assets: Initial tests of the situational crisis communication theory. Manag. Commun. Q. 2002, 16, 165–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenhausen, G.V. Emotions, arousal, and stereotypic judgments: A heuristic model of affect and stereotyping. In Affect, Cognition, and Stereotyping: Interactive Process in Group Perception; Mackie, D.M., Hamilton, D.L., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1993; pp. 13–37. [Google Scholar]

- Raykov, T. Equivalent structural equation models and group equality constraints. J. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1997, 32, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedor, C. Stereotypes and prejudice in the perception of the “other”. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 149, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, W.T.; Holladay, S.J. Exploratory study of stakeholder emotions: Affect and crisis. In Research on Emotion in Organizations: Volume 1: The Effect of Affect in Organizational Settings; Neal, A.M., Wilfred, Z.J., Charmine, H.E.J., Eds.; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 263–280. [Google Scholar]

- Coombs, W.T. Further explorations of post-crisis communication and stakeholder anger: The negative communication dynamic model. In Proceedings of the 10th International Public Relations Research Conference “Roles and Scopes of Public Relations”, South Miami, FL, USA, 8–11 March 2007; pp. 59–69. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, L.M.; Sparks, B.; Glendon, A.I. Stakeholder reactions to company crisis communication and cause. Public Relat. Rev. 2010, 36, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenhausen, G.V.; Sheppard, L.A.; Kramer, G.P. Negative affect and social judgment: The differential impact of anger and sadness. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 24, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B. An Attribution theory of Motivation and Emotion. In Series in Clinical & Community Psychology: Achievement, Stress, & Anxiety; Hemisphere Publishing Corporation: London, UK, 1982; pp. 223–245. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, W.; Amirkan, J.; Folkes, V.S.; Verette, J.A. An attribution analysis of excuse giving: Studies of a naive theory of emotion. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 52, 316–324. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner, B. Judgments of Responsibility: A Foundation for a Theory of Social Conduct; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).