Abstract

Background: A particular challenge in the work to realize the global goals for sustainable development is to find ways for organizations to identify and prioritize organizational activities that address these goals. There are also several sustainability initiatives, guidelines and tools to consider when planning, working with and reporting on sustainable development. Although progress has been made, little has been written about how organizations rise to and manage the challenge. The paper explores how organizations address sustainable development, which sustainability aspects they prioritize and whether previous research can improve the priority process by using materiality analysis approach. Methods: A case study approach was chosen. Data was collected by interactive workshops and documentation. The participating organizations were two Swedish municipalities; Results: The municipalities have introduced a number of sustainability aspects into their organizational governance, especially in terms of society, human rights and the environment. A materiality analysis was conducted to determine the relevance and significance of sustainability aspects. The result shows that climate action, biodiversity and freshwater use are aspects that should be prioritized; Conclusion: The materiality analysis methodology chosen for prioritizing of sustainability aspects was useful and easy to work with. However, the sustainability aspect matrix and the risk assessment have to be updated regularly in order to form an effective base for the materiality analysis.

1. Introduction

Sustainable development is now a widely accepted concept for nations, organizations and individuals. Global sustainability goals include the elimination of poverty, health for all, social justice [1] and meeting the needs of society while living within the planet’s ecological limits and without undermining the needs for future generations [2]. Planetary boundaries that must not be transgressed have been identified and quantified, where crossing certain biophysical thresholds could have disastrous consequences for humanity. The planetary boundaries could therefore help to prevent human activities causing unacceptable environmental change and define a safe operating space for humanity [3,4]. This indicates that organizations should analyze their activities and relate them to global requirements, as exemplified by ideas presented in the Science Based Targets, which suggest how organizational goals can be linked to global goals for carbon reductions [5]. Generally, it could also be argued that organizations should relate their goals to external goals [6].

In September 2015, 193 world leaders agreed to 17 global goals for sustainable development. If these goals are met it will mean an end to extreme poverty, inequality and climate change by 2030 [1]. Agenda 2030 is the framework and the overall strategy document that has been adopted for achieving the goals [7]. Although Agenda 2030 is for nations, it could also help organizations to identify the relevant sustainability aspects to work with.

In order to move from agreement to implementation and goal achievement there must be great attention on interlinkages and interdependencies among sustainable development goals across sectors, societal actors and countries [8]. In many countries, public organizations are important as role models and examples when introducing new priorities and focusing on the common good. They also play an important role in paving the way for the realization of global goal initiatives at a national level. According to Robecosam [9], Sweden is at the forefront when it comes to sustainability and it is the Swedish Government’s ambition that the country will take the lead in implementing Agenda 2030 and contribute to its global implementation. The Swedish action plan [10] states that municipalities, county councils and regions play key roles in the implementation of Agenda 2030, that the commitment to Agenda 2030 is wide and that there is every likelihood that Agenda 2030 will have a major impact at the local and regional level.

At an organizational level there are sustainability initiatives, guidelines and tools other than Agenda 2030 and planetary boundaries to consider when planning, working with and reporting on sustainable development. Different standards, such as the ISO 14000 family on environmental management, the ISO 26000 on social responsibility, the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) standards and the OHSAS 18001 on occupational safety and health, provide further directives. By including a multiplicity of sustainability goals, the variety of sustainability initiatives, guidelines and tools also increases the complexity of managing sustainability in organizations. Although several of the initiatives appear to conform, it may still be a challenge for individual organizations, such as a municipality, to interpret and prioritize which goals to implement and take action on, especially when organizations often have to focus on the local stakeholders that they create value for [11].

Although considerable progress has been made in recent years, little has been written about how organizations actually manage the challenge of interpreting and prioritizing sustainability goals [12,13,14]. There is a risk that achieving short term human development may undermine the capacity of the global life support system to support human well-being in the long term [15]. Furthermore, there is a risk that actors will “cherry-pick” goals perceived to be well aligned with their own current priorities and ignore goals that are perceived to be more difficult to address [8]. Some standards and frameworks advocate “materiality analyses” to determine the relevance and significance of different sustainability aspects to an organization and to its stakeholders. Thus, the central purpose of materiality analysis is to place sustainability aspects on a spectrum from less to more important [16] based on the importance of an aspect to stakeholders as well as the aspects influence on the organizational success.

Swedish municipalities state that the biggest challenge with sustainability is its comprehensiveness. It includes so many aspects and it is difficult to pick out the most important to form goals and activities. In addition, municipalities have a large number of stakeholders, all with different needs and expectations, to satisfy. This is something that the materiality analysis methodology takes into account. However, the usefulness of materiality analyses for prioritizing sustainability aspects has not been studied to any large extent.

Hence, the research in this paper is exploring the usefulness of materiality analysis for addressing the municipalities stated challenge through the following research questions: How do Swedish municipalities introduce sustainability into their operational governance and which sustainability aspects have been prioritized? Can previous research regarding materiality analysis facilitate the municipalities’ prioritization of sustainability aspects?

The paper is organized as follows: First, the theoretical framework is presented. The research methods are then described, together with a brief presentation of the case organizations. This is followed by the findings, where the participating organizations’ sustainability practices and a framework for prioritizing and analyzing sustainability aspects are described. Finally, the conclusions are presented and discussed.

2. Materiality Analysis to Guide Sustainability

Although it is possible for nations to successfully interpret and implement the global goals, there are several challenges to doing this at an organizational level [17]. One major challenge is to identify “which” sustainability aspects to include in the communication in order to fulfil the information needs of stakeholders that can affect long-term business performance [18]. One way of addressing this has been for organizations worldwide to increasingly adopt sustainability reporting [19,20]. A problem with the current frameworks for sustainability reporting is a lack of standardization, which makes it difficult to compare the reports of different organizations. One way of tackling this problem is to apply a so-called “materiality analysis” to determine the relevance and significance of an aspect to an organization and its stakeholders [21,22]. In a materiality analysis, each aspect should be assessed in terms of “significance to stakeholders” and “significance to the organization” to determine materiality and priority. Organizations have used this materiality analysis approach as a legitimate tool to determine material aspects. However, the quality of the analysis seems to vary. One reason for this is that no consistent framework exists [23].

Some studies have been identified in which different materiality analysis approaches are suggested. Hsu et al. [23] employed three FMEA indices: (i) occurrence (O), which can be determined from the percentage of concerned stakeholders, (ii) likelihood of being detected (D), which refers to the level of concern among stakeholders and (iii) severity (S), which can be quantified from the impact of issues on the strategic communication objective. An analytic network process was applied to determine the relative weights of the three indices. A risk priority number of materiality analysis was then calculated for each issue. Calabrese et al. [24] suggested a model for materiality analysis and stakeholder engagement based on the classification of customer feedback by comparing three aspects of CSR commitment (disclosed, perceived and expected). Even though the focus was on customers, the authors stated that the model could be applied to any stakeholder group. Another quantitative method was proposed by Calabrese et al. [25] called a “fuzzy analytic hierarchy process” method. This method addressed critical issues of subjectivity, completeness and resource limitations of SMEs. A materiality analysis by Font et al. [26] compared stakeholder concerns/demands with both the relevant literature and existing sustainability reports in order to determine the extent to which industry’s definition of its social responsibility matched the expectations of its stakeholders.

The materiality analysis methodology is, as mentioned before, used today in both companies and other organizations. Since the participating organizations early in the project communicated the need to prioritize sustainability aspects and focus on those that are essential, we have chosen to explore if the methodology also can be used for public governance. In addition, municipalities have a large number of stakeholders, all with different needs and expectations, to satisfy. This is something that the materiality analysis methodology takes into account. This paper is primarily inspired by Whitehead’s [16] prioritizing of sustainability aspects by using a materiality analysis to guide sustainability assessment and strategy. Whitehead [16] highlights different information sources that are useful for prioritizing aspects that take a diverse array of stakeholder perspectives into account. Five different stakeholder perspectives are represented in Whitehead’s study: scientific, regulatory, consumer, societal and business/industry. A meta-analysis identifies sustainability aspects that relate to stakeholder perspectives and to information sources that are codified and ranked. The more often a particular sustainability aspect is found to be present in multiple sources of information, the more salient it is considered to be. Whitehead [16] also considers potential risk to be an important characteristic of sustainability aspect priority. Risk is understood as the potential severity of consequences that an aspect may have for the organization. The findings of the risk assessment are in turn codified on a three-point scale.

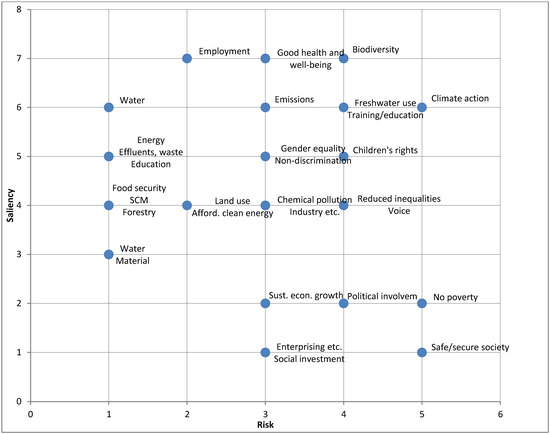

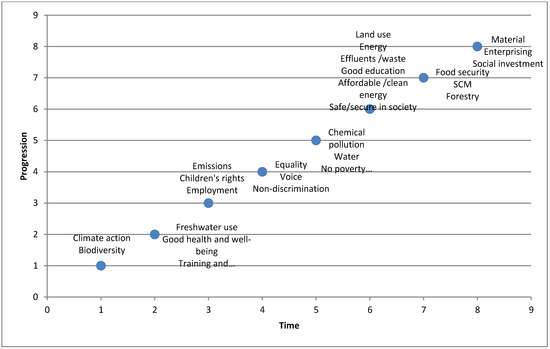

The findings are then plotted on a two-axis chart to provide a picture of sustainability aspects priority. The aspects in the lower left-hand corner of the chart (see Figure 1) signify that they have relatively low saliency and low risk. Those in the upper left-hand corner represent aspects that have high saliency yet low risk. The lower right-hand corner of the chart contains aspects that have high risk but low saliency. Finally, in the upper right-hand corner are the aspects with higher levels of risk and saliency and consequently those that should be given priority. The final step in Whitehead’s [16] methodology is to plot the sustainability aspects in order of priority (see Figure 2). Progression is shown on the y-axis, while time is displayed on the y-axis. Thus, the plot shows a progression through increasingly lower priority aspects over time. Altogether, these two charts visualize the different aspects that an organization needs to consider and how these can be prioritized. Thereby, they can also be used as a check in strategic discussions within the organization on how to address global sustainability goals.

Figure 1.

Priority of sustainability aspects for municipality X.

Figure 2.

Sustainability aspects in order of priority for municipality X.

3. Developing a Sustainability Framework

An organization’s ability to address and implement activities that contribute to a more sustainable development is influenced by a (see Section 3.2) and a number of sustainability initiatives guidelines and tools relevant for the participating organizations (see Section 3.3). In the last Section 3.4 the sustainability number of different frameworks. In this section, a sustainability framework called the sustainability aspect matrix is developed. It is based on a scientific framework (see Section 3.1), a global regulatory framework aspect matrix is developed.

The development is inspired by Whitehead [16] who highlights different information sources that are useful for prioritizing aspects that take a diverse array of stakeholder perspectives into account. Five different stakeholder perspectives are represented in Whitehead’s study: scientific, regulatory, consumer, societal and business/industry. The sustainability framework developed in this paper is based on a scientific and a regulatory part and consists of contributions which may facilitate prioritization of sustainability aspects. The scientific framework is based on the planetary boundaries and a safe and just operating space for humanity since these contributions indicates the importance that organizations should analyze their activities and relate them to global requirements for a sustainable development. Scientific knowledge is important for understanding the consequences of an aspect, as well as informing policy formulation and societal perceptions [16]. The regulatory framework includes the UN’s global goals, Agenda 2030 and the Swedish national environmental objectives. Regulation addresses sustainability issues that can have a direct impact on industries through added costs or restrictions [16]. The global goals and the Agenda 2030 are also important contributions that indicate the importance that organizations relate activities to global requirements for a sustainable development. Whitehead’s [16] consumer, societal and business/industry perspectives are exchanged for other sustainability initiatives more relevant for public governance. A number of sustainability initiatives, guidelines and tools mentioned, referred to or highlighted by the participating organizations in their communication with stakeholders also form the basis for the development of the sustainability aspect matrix. The initiatives, guidelines and tools are addressed and therefore considered important to the participating organizations and should be complied in order to avoid greenwash. Hence, the sustainability framework will consist of sustainability aspects that are relevant from a global perspective for sustainable development but also sustainability aspects that should be relevant for the participating organizations. This matrix is developed for a Swedish perspective and applicable to Swedish municipalities. The matrix will be used to analyze the Swedish municipalities’ sustainability practice and to prioritize sustainability aspects.

The described approach for the development of the sustainability framework can be used for other organizations, countries, businesses or industries and will generate a framework that is specific and relevant for the case chosen. However, then there may be other scientific and regulatory frameworks that are more relevant and other sustainability initiatives, guidelines and tools that are communicated and applicable.

3.1. Scientific Framework—A Safe and Just Operating Space for Humanity

Rockström et al. [3,4] have identified and quantified planetary boundaries that define a safe operating space for humanity. In order to avoid disastrous consequences, these boundaries must not be transgressed. Four of the nine planetary boundaries-climate change, loss of biosphere integrity, land-system change, altered biogeochemical cycles (phosphorus and nitrogen)-have already been crossed as a result of human activity [27]. Two of these—Climate change and biosphere integrity are what the authors call “core boundaries”. Significantly altering either of these would drive the Earth System into a new state. Transgressing a boundary increases the risk that human activities could inadvertently drive the Earth System into a much less hospitable state, thereby jeopardizing efforts to reduce poverty and leading to deterioration in human well-being in many parts of the world, including wealthy countries. Hence, even though staying within a safe operating space for all nine boundaries is important, reducing our negative impact on biodiversity, climate change, the nitrogen cycle and land-system change is both vital and urgent.

A common request since their publication has been to downscale the planetary boundaries to the levels of countries, organizations and individuals. This is necessary in order to identify activities at all these levels that contribute to and enable us to stay within the “safe operating space”. In line with this, Nykvist et al. [17] have explored whether the planetary boundary framework could be downscaled to nationally relevant boundaries and whether indicators and data are available that allow comparisons of country performances. The study has a Swedish perspective and shows that the planetary boundaries can easily be linked to Sweden’s national environmental objectives, which are further described in Section 3.2 Regulatory framework. Nykvist et al. [17] recommend that additional consumptive-based indicators, covering each of the planetary boundaries, can be used to complement the existing indicators to assess whether nations are meeting their generational goals.

Raworth [28,29] claims that environmental sustainability alone, without any reflection on social outcomes, will not achieve sustainable development. Combining planetary and social boundaries creates a new perspective on sustainable development. Human rights advocates have long highlighted the imperative of ensuring every person’s claim to life’s essentials, while ecological economists have emphasized the need to situate the global economy within environmental limits. The framework, called the doughnut, presented by Raworth [28,29], brings the two together and creates a space that is bounded by both human rights and environmental sustainability, while at the same time acknowledging that there are many complex and dynamic interactions across and between the multiple boundaries.

The doughnut combines two concentric radar charts to depict a social and an ecological boundary that together encompass human well-being. The inner boundary is a social foundation, below which lie shortfalls in well-being, such as hunger, ill health, illiteracy and energy poverty. Its twelve dimensions are derived from internationally agreed minimum standards for human well-being [30]. The outer boundary is an ecological ceiling, based on the nine earth system processes within the planetary boundaries framework [27]. Between these two sets of boundaries lies an ecologically safe and socially just space in which the whole of humanity has a chance to thrive [30].

Dearing et al. [31] show that the doughnut is applicable on a regional scale. The authors argue that such a framework can: (1) increase the policy impact of the boundaries concept, since most governance takes place on the regional rather than the planetary scale; (2) contribute to the understanding and dissemination of complexity thinking throughout governance and policymaking and (3) act as a powerful metaphor and communication tool for regional equity and sustainability. The authors demonstrate that the framework helps to raise the standards of social conditions while reducing the risk of moving into dangerous operating spaces with respect to ecological boundaries. The framework also offers a clear visual image for making comparisons between different regions and provides a basis for assessing a region’s impact on the planetary boundaries.

Dearing et al. [31] show that the doughnut framework which includes both planetary and social boundaries is applicable on a regional scale. Even though a Swedish municipality operate on a local scale it often covers large land areas which includes both rural and urban areas. Therefore, the result presented by Dearing et al. [31] is applicable in a Swedish municipality context.

3.2. A Global Regulatory Framework

In September 2015, 193 world leaders agreed to 17 global goals for sustainable development. If these goals are achieved, it will mean an end to extreme poverty, inequality and climate change by 2030 [1]. The goals include all dimensions of the triple bottom line and are presented and briefly described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Global goals for sustainable development, with general descriptions.

Each goal has a number of targets. Even if the goals mostly target the developing world, universal targets can be found within all the goals and should also therefore be of great importance and applicable in the developed world. Agenda 2030 is a plan of action for achieving the global goals. All countries and all stakeholders, acting in collaborative partnership, are expected to implement this plan [7].

The Swedish Government has appointed a Swedish delegation to promote, facilitate and stimulate the implementation of Agenda 2030. In its official report, towards a sustainable welfare, it claims that the implementation requires a committed leadership that is long-term and cross-sectorial [32]. The ambitions, values and actions are crucial in order to clarify how priorities are to be set and how operations are to be managed. Another important prerequisite for implementing the Agenda and achieving the global goals is a strong partnership between different actors in society. Additionally, the Swedish Government has developed 16 national environmental objectives that describe the quality of the environment that Sweden wishes to achieve by 2020. The objectives cover different areas, from unpolluted air and lakes free from eutrophication and acidification, to functioning forest and farmland ecosystems. For each objective, there are a number of “specifications”, each of which clarify the state of the environment to be attained [33].

3.3. Sustainability Initiatives, Guidelines and Tools

Besides the global goals, the Agenda and the national environmental objectives there are a multitude of global sustainability initiatives, guidelines and tools available. Some are more general and aimed at many different types of companies and organizations. Others have a clearer focus on a particular operation or type of industry. In Table 2, the initiatives, guidelines and tools relevant for the participating organizations are presented. The relevance has been assessed based on the fact that the participating organizations communicate compliance with these various initiatives, for example via websites and documentation (see data collection, 4. Methodology).

Table 2.

Important sustainability initiatives for the participating organizations.

The initiatives have different approaches and include different sustainability criteria. Some focus on one single subject, for example the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the UN’s Convention against Corruption, while others embrace several subjects, such as the SS 854000:2014 and the GRI framework. The scientific and regulatory framework along with the sustainability initiatives, guidelines and tools presented here enable us to generate a list of sustainability aspects which are relevant for the specific organizations participating in this study. The sustainability aspects are then structured into core subjects and compiled into a sustainability aspect matrix.

3.4. The Sustainability Aspect Matrix

The sustainability framework which consist of the scientific and regulatory framework along with the sustainability initiatives, guidelines and tools relevant for the participating organizations enable us to generate a list of sustainability aspects. This was done by reading, analyzing and raising all sustainability aspects found in the sustainability framework. In some cases, the aspects coincided, that is to say, the same aspects were found in a number of documents. In other cases, new aspects were found and added to the list. As mentioned before, some of the documents focus on one single subject while others embrace several subjects. For example, the standard SS 854000:2014 added a large number of sustainability aspects whereas the UN’s Convention against Corruption only generated one. The sustainability aspects identified are then structured into core subjects and compiled into a sustainability aspect matrix, see Table 3. In the left-hand column, the core objects—The environment, human rights, labor practices, fair operating practices, society, economic aspects, customer responsibility and global challenges—are listed. Several sustainability aspects are presented under each core subject. In the columns that follow, sustainability initiatives from the UN global goals and the Agenda 2030 to ISO 9001:2015 are presented. An “X” marks whether or not the sustainability aspect is addressed. For example, Agenda 2030 addresses all the sustainability aspects in the core subject of the environment, except recycling and radiation. In the far left-hand column, “summary”, the “X” is summarized in terms of how many of the sustainability initiatives the sustainability aspect addresses. Climate action is, for example, addressed in 6 of the 14 sustainability initiatives. Since the sustainability matrix consisted of a large number of sustainability aspects a decision was made to simplify the materiality analysis. The sustainability aspects that generated a higher score (n > 3) in the matrix are regarded as more important. The sustainability aspects that generated a lower score (n ≤ 3) in the matrix are regarded as less important. Thus, it is the sustainability aspects with a higher score that is used for the materiality analysis further described in Section 5.2.

Table 3.

The sustainability aspect matrix. Core subjects and sustainability aspects identified in the theoretical framework and in sustainability initiatives.

The most discussed aspects in the scientific and regulatory framework along with the sustainability initiatives, guidelines and tools are those within the core subjects—labor practices, human rights, the environment and society. For labor practices, the aspects are full and secure employment and decent working conditions and human development and training in the workplace. For human rights an important aspect is food, which includes ending hunger, achieving food security and improving nutrition and so forth. Good health and well-being, good education and affordable and clean energy for all are also important aspects. Gender equality, non-discrimination, reduced inequalities among people and children’s rights are often mentioned, as is the abolition of forced and compulsory labor. The core subject environment generated the largest variety of important sustainability aspects. The sustainable use of material, energy and water is important, as is the prevention of pollution by reducing emissions to air, discharges to water, the use and disposal of toxic and hazardous chemicals and waste management. Other aspects are climate action, biodiversity and the use of land and fresh water. Some initiatives are more specific and list the problems associated with the different forms of pollution, such as ocean acidification, chemical pollution, atmospheric aerosol pollution and stratospheric ozone depletion. For society, the initiatives most emphasized in the sphere around municipalities focus on industry, innovation and infrastructure, which is also one of the global goals for sustainable development.

The approach presented here generates a matrix that consists of sustainability aspects relevant for the specific participating organizations studied in this paper. The matrix will later on be used to analyze the Swedish municipalities’ sustainability practice and to identify the prioritized sustainability aspects. This is further described in Section 4. Methodology.

4. Methodology

The research presented in this article used a case study approach, because an important aim of the research was to investigate social phenomena in real-life contexts (see also [34,35]). A case study was designed and participating organizations were selected based on a high sustainability profile, for example by being highly placed in the Swedish ranking of municipal sustainability work, where criteria such as the implementation of Agenda 2030, established climate objectives, environmental management system certifications, responsible supply chain management, energy efficiency management and so forth, are evaluated. The participating organizations were the two Swedish municipalities.

Data was collected through interactive workshops and from documentation. Interactive research is based on the joint learning of the participants and researcher throughout the entire process [36], to which researchers can contribute in multiple ways [37]. Three interactive workshops were conducted during one-day visits and were held at the premises of the collaborating organizations (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Information about the workshops.

The project was initiated at an interactive workshop (WS1) in which the scope and the boundaries for the project were discussed. The organizations also presented their challenges and priorities with organizational governance for a sustainable development. The following step was to collect data on the participating organizations’ sustainability efforts. Initially, a study of the organizations’ communications was carried out based on the information and documentation published on their websites.

Documents play an explicit role in case study data collection and systematic searches for relevant documents are important [35]. In this case study, the documentation comes from the participating organizations’ websites or is provided by the participants from the respective organizations. The studied documents consist of documented information such as policies and activating documentation such as programs and action plans. The documentation studied for the participating organizations is presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Information about the documentation.

During the documentation study and the workshops, a variety of sustainability initiatives important for sustainability governance were identified. These are presented in Section 4 and Table 4.

The next step was to develop a sustainability aspect matrix based on the theoretical framework and a review of the sustainability initiatives, guidelines and tools presented in Section 2 and Table 3. The purpose here was to identify sustainability aspects regarded in the initiatives as symbolizing the stakeholder interests inspired by the methodology described by Whitehead [16]. The content was coded into aspects and the aspects were organized into core subjects. Preliminary results were presented at the second workshop (WS2). The participating organizations were invited to comment on the result and to complement with more sustainability initiatives and internal documentation. This resulted in both the matrix and the analysis being updated. The aspects in the different initiatives are summarized in the final column in the matrix. The aspects with the highest scores (n > 3) are consequently the most salient. The final result is presented in Table 6 in Section 4.

Table 6.

The analysis of how well the sustainability practice corresponds with the sustainability matrix.

The final step is based on the methodology presented by Whitehead [16]. Here, the participating organizations performed a risk assessment during the third workshop (WS3), where the risk was understood as the potential severity of consequences an aspect could have for the organization and the likelihood of harm. The saliency from the first step was then plotted against the risk assessment. The result is presented in Section 4 and Figure 1. In the final step, the sustainability aspects for the participating organizations were plotted (see Section 4 and Figure 2).

5. Findings

The result from the case study is presented in this section. The participating organizations and their sustainability efforts are outlined in Section 5.1. In Section 5.2 the analysis of how well the organizations’ sustainability practice corresponds with the sustainability aspect matrix is presented and the methodology presented by Whitehead [16] is tested.

5.1. The Participating Organizations

The participating organizations are the two Swedish municipalities X and Y, here presented from a sustainability perspective. The presentation is based on reviews of their websites and annual reports, complemented with data/information from internal documentation and interactive workshops.

5.1.1. Municipality X

Municipality X is Sweden’s fourth most populated municipality with approximately 216,000 inhabitants. It is located in central Sweden and has a land area of 2234 km2. The concepts “sustainable development” and “sustainability” are not prioritized on the first page of the municipality’s website. However, when using the search function, the concepts generate a number of hits.

The municipal executive board produces an annual report in which the progress of sustainable development is discussed. In the 2016 version, Agenda 2030 and the global development goals form a central part. The sustainability efforts in the report are summarized under the three headings of economic, social and environmental sustainability. Economic sustainability includes community growth, more companies, business growth and cooperation both within the region and internationally. Social sustainability embraces the respect for human rights, democracy through participation and social investments. Environmental sustainability includes climate change and renewable energy, non-toxic environment, safe water management and sustainable exploitation, biodiversity and ecosystem services. The policy for sustainable development includes the subjects of democracy and equality, economy, public health and environment and climate.

The established objectives and budget for the period 2017–2019 are based on nine main targets: an equal and sustainable economy, the community should be attractive to live, work and stay in, sustainable growth in both city and countryside, equal, with good living conditions, residence and work, children and students should complete their education and be challenged in their learning, residents shall live independent lives and receive support based on their needs, residents and organisations should be involved in the development of society and Municipality X’s employees should have good working conditions and great competence. Activities are identified for each target and indicators are developed and ranked.

The control documentation that supports the established objectives and budget is structured into programs, policies, action plans and guidelines. An important example of a program is the environment and climate program, where one of the long-term goals is that X should be a fossil fuel-free welfare municipality that provides solutions to global ecological recovery and welfare. The community should be fossil-free in 2030 and climate-positive in 2050. The other long-term goal is a non-toxic environment, where the presence of substances in the indoor and outdoor environment, created or extracted by society, should not threaten human health or biodiversity. In order to reach the long-term goals, eight targets are presented:

- Renewable and climate-neutral heating by 2020

- Solar energy—30 MW solar energy by 2020

- Fossil fuel-free municipal vehicle park by 2020, as well as fossil fuel-free machinery and climate-neutral transports by 2023

- 25% more energy-efficient by 2020

- Sustainable procurement for a non-toxic environment by 2020

- 100% organic food by 2023

- Increase sustainable construction and management

- Sustainable business, operations and green jobs

Two examples of policies included in this study are the policy for sustainable development and the procurement policy. The policy for sustainable development includes the subjects of democracy and equality, economy, public health and environment and climate. In the procurement policy, the concept “sustainable procurement” is proclaimed in order to “contribute to social development, environmental and climate-driven business development and ethically sustainable production of goods and services”. More specifically, it is about contributing to the municipality’s environmental and climate goals, promoting good working conditions and gender equality in working life, following labor market conditions and collective agreements and counteracting discrimination and corruption.

Municipality X also have a great amount of action plans and guidelines supporting programs and policies that are not included in this study since their degree of detail is not necessary for this study. The control documents included in this study is presented in Table 5.

5.1.2. Municipality Y

Municipality Y is Sweden’s sixth most populated municipality with approximately 150,000 inhabitants. Municipality Y is the main town in the county and is located in central Sweden with an area of 1380 km2 (land area). In the municipality there are residents from around 165 different countries. The city itself is more than 700 years old.

The concepts “sustainable development” and “sustainability” are not prioritized on the first page of the municipality’s website. However, when using the search function, the concepts generate a large number of hits. The municipal executive board and committees produce an annual report and, in the 2016 version, sustainable growth, people’s empowerment, children and young people’s needs and welfare securement are in focus. Sustainable growth means companies establishing, growing and developing in the municipality, good communications for citizens and a reduced climate impact. People’s empowerment means that citizens can contribute to the development of the municipality but also includes coordination for a well-functioning refugee reception and service equality. Children and young people’s needs include social investments, working according to the action plan against child poverty, the implementation of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and so forth. A safe welfare is also highlighted in order to increase the perceived safety of people and here crime prevention is mentioned. Self-assessment has been conducted in relation to the municipal executive board’s contribution to development in these four strategic areas, where the rating is green for them all, thus indicating that the goals will be reached.

Municipality Y’s control documentation is structured into programs, policies, strategies, action plans and guidelines. A program expresses the value base and desirable development in the municipality. The policy states a value-based approach and principles for guidance. A strategy confirms a program or policy and provides a basis for priority. An action plan describes objectives and actions and the guidelines ensure proper action and good quality when activities are handled and performed.

One important program included in this study is the environmental program that describes the municipality’s environmental work. The program is divided into five focus areas; climate, biodiversity, water, non-toxic environment and a good built environment. For each focus area overall and detailed environmental objectives, implementation activities and references to underlying documentation are presented.

An example of a policy is the procurement policy with a value-based approach. This means that sustainable procurement requires a holistic view, where the municipality should ensure that purchases are made in economically, socially and ecologically sustainable ways that comply with agreements, laws and regulations. The citizens should feel confident that the municipality chooses goods, services and contracts that provide good cost-effectiveness with low environmental impact. The procurement should contribute to the innovation of new environmental technologies, as well as ensure good environmental and health, economic and social welfare and justice for present and future generations. The life cycle perspective is fundamental in calculating cost-effectiveness.

One important example of a strategy is the climate strategy that was adopted in June 2016. The climate strategy includes the long-term goal that the climate load per person in Municipality Y which, if applied globally, should be at a level that does not endanger the Earth’s climate. The strategy is developed in stages, where the municipality as a geographical area should reduce climate load by 100% in 2045 by using climate policy instruments, renewable electricity generation, energy efficiency measures, district heating, biogas and so forth. The objective for the municipality as an organization is to be climate neutral by 2030 by means of energy efficiency measures, the municipality’s fleet becoming more climate-friendly, an increase in the use of renewable fuels, a reduction in food waste within the municipality’s organization, an increase in the purchase of organic and near-produced food and so on. The climate strategy is ambitious, as can be seen by the goals/sub-goals and indicators that have been developed and presented. Municipality Y also have a great amount of action plans and guidelines supporting programs, policies and strategies that are not included in this study since their degree of detail is not necessary for this study. The control documents included in this study is presented in Table 5.

A new position as sustainability manager was established in 2017 in order to support ecological, social and economic sustainability and achieve the Agenda 2030 goals. The sustainability manager’s overall task is to ensure that sustainability work permeates all the municipality’s activities.

5.2. Sustainability Performance of Two Swedish Municipalities

The sustainability practices of the municipalities are correlated to the sustainability aspect matrix as shown in Table 6. The core objects from Table 3 are listed in the left-hand column: environment, human rights, labor practices, fair operating practices, society, economic aspects, customer responsibility and global challenges. Several sustainability aspects are presented under each core object. The column “summary” corresponds to how the sustainability aspects are addressed by the scientific and regulatory framework along with the sustainability initiatives, guidelines and tools (see Table 3, Section 3). The “X” in the columns for Municipality X and Y marks which sustainability aspects are addressed by the municipalities.

Municipality X has focused its environmental efforts on climate action, biodiversity, land use, freshwater use, chemical pollution and the sustainable use of energy and water, which correspond well with the result in the matrix. However, it has not prioritized the prevention of pollution by reducing emissions to air, discharges to water and waste management, which also generated a high score in the matrix. Instead, Municipality X has prioritized ecosystem services, which generated a lower score (n ≤ 3) in the matrix. Municipality Y has also targeted climate action, biodiversity, freshwater use, chemical pollution, waste, recycling and the sustainable use of energy and water. Y has chosen not to focus on other important aspects in the matrix, such as land use and the reduction or elimination of pollution through emissions and effluents.

Regarding the core subject human rights, the matrix complies well with the municipalities’ prioritized aspects. The only difference is that X has preferred the aspect indigenous rights/national minorities, which is not highlighted in the matrix. On the subject of labor practices, the matrix complies well with Municipality X. Municipality Y has also prioritized employment and decent working conditions but has chosen the aspect occupational health and safety before training and education in the work place. In terms of fair operating practices, the municipalities have prioritized anti-corruption and responsible supply chain management, both of which are in line with the matrix.

Also apparent from the matrix is that the core subject society generated many aspects but none that were considered overly important. However, society is a very important area for both municipalities. Aspects such as sustainable communities, reduced inequalities, industry, innovation and industry, enterprising and entrepreneurship, culture and art, sustainable transports, employment creation and skills development, safety and security in society and social investments are all regarded as important. Municipality X also highlights sustainable industry and forestry.

Economic aspects and customer responsibility are of less importance in the initiatives summarized in the matrix. However, both municipalities highlight sustainable economic growth. Additionally, X has chosen to prioritize the aspect products and services. The matrix identified peace, justice and strong institutions, whereas the municipalities instead preferred to work with partnership, both locally and internationally.

In the last workshop, municipality X, conducted a risk assessment, where the risk was understood as the potential severity of consequences an aspect could have for the organization and the likelihood of harm. The risk assessment was initiated in a discussion about how to tackle the task. The issue was to determine whether it should look at the numerous sustainability aspects from a general perspective or from a municipality perspective and take previous work into account. It decided on the latter. In the column “estimation of risk” in Table 6, the municipality’s estimation of “potential severity of consequences an aspect could have for the organization” is presented, where 1 is the lowest risk and 5 the highest. The saliency from the first step was then plotted against the risk assessment. The result is presented in Figure 1. Note that on several occasions a dot represents several sustainability aspects.

Figure 1 shows the result of combining the overall saliency and risk scores across the sustainability aspects. The sustainable use of water and material is located in the lower left-hand corner, signifying that these aspects have relatively low saliency and low risk for Municipality X. Aspects with high saliency yet low risk are represented in the upper left-hand corner of Figure 1. These aspects are the use of water and energy, effluents and waste, good education for all, food security, sustainable supply chain management, sustainable forestry and land use and providing for affordable and clean energy. The lower right-hand corner of Figure 1 contains aspects with high risk but low saliency. These aspects are highly specific to the municipality. Here we find no poverty, responsible political involvement, to feel safe and secure in society, sustainable economic growth, enterprising and entrepreneurship and social investment. A large number of aspects are located in the upper right-hand corner of Figure 1, signifying that these issues have higher levels of risk and saliency. Environmental aspects are climate action, biodiversity, freshwater use, emissions and chemical pollution. The human rights aspects are good health and well-being, children’s rights, gender equality, reduced inequalities, non-discrimination and voice. The labor practice aspect of training and education in the workplace is also located here.

The sustainability aspects for the municipality X are plotted in order of priority in Figure 2. The priority is calculated by adding the terms from saliency and risk. The sustainability aspects are plotted as a descending scale, where the highest sum becomes number one in priority, the second highest sum becomes number two in priority and so on. Thus, the order of priority should be read from the left to the right in the table. However, some aspects generate the same sum and are consequently plotted in the same position.

Figure 2 presents the most prioritized aspects in order of priority. The progression is shown on the y-axis, while time is displayed on the x-axis. The highest priority aspects are expected to be addressed first. Figure 2 thus demonstrates a progression through increasingly lower priority aspects over time. The figure shows that the aspects climate action and biodiversity are the most urgent to address.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

The research presented in this paper addresses the following questions: How do Swedish municipalities introduce sustainability into their operational governance and which sustainability aspects have been prioritized? Can previous research regarding materiality analysis facilitate the municipalities’ prioritization of sustainability aspects?

A case study approach was chosen and data was collected in three interactive workshops and by means of documentation such as policies, strategies, objectives, annual reports, programs and guidelines. A sustainability aspect matrix was developed, based on a scientific and regulatory framework along with the sustainability initiatives, guidelines and tools relevant for the participating organizations. These fourteen sources (see Table 3) are considered to reflect the needs and expectations of a range of stakeholder groups important for the participating organizations since the influence of different stakeholder groups has been recognized as a key factor in sustainability initiatives [38]. The matrix consists of a large number of sustainability aspects organized into the core subjects of environment, human rights, labor practices, fair operating practices, society, economic aspects, customer responsibility and global challenges. The most salient sustainability aspects corresponded well with the global sustainability goals and the nine planetary boundaries [3,4] and especially well with the “core boundaries” of climate change and biodiversity [27]. Hence, the sustainability aspect matrix was, as mentioned before, considered to reflect the needs and expectations of a range of stakeholder groups and underlies the analysis of the municipalities’ sustainability efforts. When comparing the resulting sustainability framework in Whitehead’s [16] study with the framework (the sustainability aspect matrix) featured in this paper, there are some differences. This is due to the fact that the context in Whitehead’s [16] study is the New Zealand wine industry and the focus in this study is the Swedish municipalities. The strength of Whitehead’s [16] methodology is that it develops a sustainability framework that is applicable in the specific context that you choose to study. This indicates that the methodology is applicable and useful for different contexts such as other countries, businesses or industries. However, then there may be other scientific and regulatory frameworks that are relevant and other sustainability initiatives, guidelines and tools that are applicable.

The analysis of the municipalities’ sustainability efforts shows that they have introduced a large number of sustainability aspects into their organizational governance. Similarities between the matrix and both municipalities are especially found in the core subjects of the environment and human rights. For the environment, the aspects are climate action, biodiversity, freshwater use, chemical pollution and a sustainable use of energy and water. For human rights, the aspects are food security, good health and well-being, good education, equality, voice, children’s rights and non-discrimination. However, there are also aspects especially within the core subject of the environment that the municipalities have not prioritized for example the nitrogen and phosphorus cycles, ocean acidification, atmospheric aerosol pollution and stratospheric ozone depletion. These foremost come from the global initiatives, that is, the global goals and the Agenda 2030, the planetary boundaries and the doughnut for the Anthropocene. This indicates that the municipalities’ sustainability governance is not related to global and external goals which are a prerequisite for achieving sustainable development. By using the methodology tested in this paper organizations will develop a sustainability framework that has included this global dimension.

The matrix has some limitations. It cannot be directly applied to another type of operation, business or industry but must be adapted to the specific context. For example, the Agenda 2030 and the standard SS 854000:2014 Management system for sustainability in communities are highly relevant for the public sector. When a similar matrix was developed in the Nordic mining industry it looked quite different where other initiatives, for example the UN Global compact and the towards sustainable mining guiding principles were more relevant [39]. The fact that the matrix is considered to reflect the needs and expectations of a range of stakeholder groups can be discussed. This approach has been tested before and considered useful for the prioritization of sustainability aspects [16]. However, the order of priority would perhaps look different if the prioritization of sustainability aspects would have been done by the municipalities’ stakeholder groups. This could be an interesting area for future research.

Early on in the project, the respondents indicated that the biggest challenge with sustainability was its comprehensiveness. It included so many aspects and that it was difficult to pick out the most relevant. In order to determine the relevance and significance of the sustainability aspects, we decided to test the usefulness of the materiality analysis methodology for the prioritizing of sustainability aspects. The materiality analysis methodology is, as mentioned before, a management tool often used in both companies and other organizations. However, it is common that such tools are useful and implemented within public governance. One example is the international standard ISO 14001 for environmental management which at first became widely used in industry but then spread to smaller companies, other organizations and public sectors. In addition, municipalities have a large number of stakeholders, all with different needs and expectations, to satisfy. This is something that the materiality analysis methodology takes into account. The methodology presented by Whitehead [16] was selected and the sustainability aspect matrix was used for the stakeholder perspective. Since the sustainability matrix consisted of a large number of sustainability aspects a decision was made to simplify the materiality analysis. The sustainability aspects that generated a higher score (n > 3) in the matrix are regarded as more important and were included. However, all aspects could have been included in the material analysis, which had then become more comprehensive and detailed. The risk understood as the potential severity of consequences that an aspect may have for the municipality was estimated by municipality X’s respondents. The result is presented in Table 6. The respondents found the methodology useful and easy to work with. However, the sustainability aspect matrix and the risk assessment have to be regularly updated in order to be an effective base for the materiality analysis. Continuing exploring the usefulness of materiality analysis within other organizations, countries, businesses or industries would be an interesting and important area for future research.

A particular challenge in the work to realize the 17 global goals is to find ways for organizations to identify, interpret and prioritize organizational activities that address these goals. The research presented here illustrates a framework that provides businesses with a practical strategic planning tool for isolating and addressing key issues [16]. The global goals and Agenda 2030 were important contributions which insure that organizations relate activities to global requirements for a sustainable development. In this way, it enables organizations to rise to and manage this global challenge and contribute to a more sustainable development.

Author Contributions

H.R. designed and conducted the research including data collection. She analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. M.C. has contributed by participating at the workshops and the writing of the manuscript. R.I. has contributed by participating at the workshops and the writing of the manuscript. R.G. has contributed by participating at one of the workshops and the writing of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The project is funded by EPSI Rating Group.

Acknowledgments

This has been a research project within SQMA—The Swedish Quality Management Academy, see www.sqma.se.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations. The Global Goals for Sustainable Development. Available online: http://www.globalgoals.org (accessed on 2 June 2017).

- United Nations. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future 1987. Available online: http://www.un-documents.net/our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2017).

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Chapin, F.S., III; Lambin, E.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.; et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 2009, 461, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Chapin, F.S., III; Lambin, E.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.; et al. Planetary boundaries: Exploring the safe operating space for humanity. Ecol. Soc. 2009, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Science Based Targets. What Is a Science Based Target? Available online: http://sciencebasedtargets.org/what-is-a-science-based-target (accessed on 28 June 2017).

- Haffar, M.; Searcy, C. Corporate reporting on sustainability context. In Proceedings of the 10th Conference of the Performance Measurement Association, Edinburgh, Scotland, 26–29 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming the World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org (accessed on 11 December 2017).

- Stafford-Smith, M.; Griggs, D.; Gaffney, O.; Ullah, F.; Reyers, B.; Kanie, N.; Stigson, B.; Shrivastava, P.; Leach, M.; O’Connell, D. Integration: The key to implementing the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustain. Sci. 2017, 12, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robecosam. Country Sustainability Ranking. Available online: http://www.robecosam.com/en/sustainability-insights/about-sustainability/country-sustainability-ranking (accessed on 11 December 2017).

- Government Offices of Sweden. Sweden and the 2030 Agenda—Report to the UN High Level Political Forum 2017 on Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.government.se/reports/2017/06/sweden-and-the-2030-agenda--report-to-the-un-high-level-political-forum-2017-on-sustainable-development/ (accessed on 30 May 2018).

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.A. Creating Shared Value. How to reinvent capitalism and unleash a wave of innovation and growth. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gond, J.-P.; Grubnic, S.; Herzig, C.; Moon, J. Configuring management control systems: Theorizing the integration of strategy and sustainability. Manag. Account. Res. 2012, 23, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lueg, R.; Radlach, R. Managing sustainable development with management control systems: A literature review. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, E.; Endrikat, J.; Guenther, T.W. Environmental management control systems: A conceptualization and review of the empirical evidence. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 136, 147–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griggs, D.; Stafford-Smith, M.; Gaffney, O.; Rockström, J.; Ohman, M.C.; Shyamsundar, P.; Steffen, W.; Glaser, G.; Kanie, N.; Noble, I. Sustainable development goals for people and planet. Nature 2013, 495, 305–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitehead, J. Prioritizing sustainability indicators: Using materiality analysis to guide sustainability assessment and strategy. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nykvist, B.; Persson, Å.; Moberg, F.; Persson, L.; Cornell, S.; Rockström, J. National Environmental Performance on Planetary Boundaries; A study for the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency; Report 6576; Swedish Environmental Protection Agency: Stockholm, Sweden, 2013.

- AccountAbility. The Materiality Report; Aligning Strategy, Performance and Reporting; AccountAbility: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, R.; Huisingh, D. Inter-linking issues and dimensions in sustainability reporting. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R. Sustainability inter-linkages in reporting vindicated: A study of European companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 51, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AccountAbility. AA1000 Stakeholder Engagement Standard; AccountAbility: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Global Reporting Initiative. G4 Sustainability Reporting Guidelines; Global Reporting Initiative: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C.-W.; Lee, W.-H.; Chao, W.-C. Materiality analysis model in sustainability reporting: A case study at Lite-On Technology Corporation. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 57, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, A.; Costa, R.; Rosati, F. A feedback-based model for CSR assessment and materiality analysis. Account. Forum 2015, 39, 312–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, A.; Costa, R.; Levialdi, N.; Menichini, T. A fuzzy analytic hierarchy process method to support materiality assessment in sustainability reporting. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 121, 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; Guix, M.; Bonilla-Priego, M.J. Corporate social responsibility in cruising: Using materiality analysis to create shared value. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, W.; Richardson, K.; Rockström, J.; Cornell, S.; Fetzer, I.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; Carpenter, S.R.; de Vries, W.; de Wit, C.A.; et al. Planetary Boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 2015, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raworth, K. A Safe and just Space for Humanity. Can We Live within the Doughnut? Oxfam Discussion Paper; Oxfam: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Raworth, K. Defining a Safe and just Space for Humanity. Is Sustainability Still Possible? The Worldwatch Institute, Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Raworth, K. A Doughnut for the Anthropocene: Humanity’s compass in the 21st century. Lancet Planet. Health 2017, 1, e48–e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dearing, J.A.; Wang, R.; Zhang, K.; Dyked, J.G.; Haber, H.; Hossain, M.S.; Langdona, P.G.; Lenton, T.M.; Raworth, K.; Brown, S.; et al. Safe and just operating spaces for regional social-ecological systems. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 28, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statens Offentliga Utredningar. I Riktning Mot en Hållbar Välfärd. Available online: https://agenda2030delegationen.se (accessed on 10 January 2018).

- Swedish Environmental Protection Agency. The National Environmental Quality Objectives. Available online: http://www.swedishepa.se (accessed on 12 December 2017).

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, L.; Aagaard Nielsen, K. Action and Interactive Research: Beyond Practice and Theory; Shaker Publishing: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Johannisson, B.; Gunnarsson, E.; Stjernberg, T. Gemensamt Kunskapande: Den Interaktiva Forskningens Praktik; University Press: Göteborg, Sweden, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Neugebauer, F.; Figge, F.; Hahn, T. Planned or emergent strategy making? Exploring the formation of corporate sustainability strategies. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2015, 25, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranängen, H.; Lindman, Å. A path towards sustainability for the Nordic mining industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 151, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).