3.1. Karonga, Malawi

The small, but rapidly growing urban centre of Karonga (Karonga Town) is located on the shores of Lake Malawi in the north of the country. Karonga’s population is projected to increase from 41,000 inhabitants in 2008 to approximately 63,000 in 2018 [

22]. The Town is vulnerable to multiple everyday, small and large disaster risks and has been affected by earthquakes, drought and floods [

8,

22]. Everyday risks such as poor quality and inadequate sanitation and unsafe water also pose significant threats for inhabitants [

23]. However, the nature and scale of risks in Karonga remains poorly understood and knowledge of vulnerabilities to disaster risks remain low [

24]. This is partly attributable to the lack of political attention and finance towards the development and governance of small, but often rapidly growing towns throughout Malawi and indeed other sSA contexts more broadly [

22].

Decentralisation was reintroduced in Malawi following multi-party elections in 1994 with many roles and responsibilities consequently devolved to the lowest level of government. Disaster risk governance in Karonga Town faces considerable challenges. Firstly, the Town’s rapid growth has led to a growing demand for services and risk reducing infrastructure, yet provision is constrained by limited capacities and funding within local government [

23]. As with other urban centres in Malawi and across sSA, growth in Karonga is largely informal, except in the commercial centre [

8]. Secondly, the local government—the Town Council—was dissolved in 2009, resulting in the Town being governed by the rural local government—the Karonga District Council. Overall, it is apparent that the rural Karonga District Council is significantly over-stretched by its mandate for governing urban development challenges, particularly due to inadequate revenue and limited direct support from the central government. This weak governance structure has resulted in poor planning and project implementation throughout the Town. There is also a lack of clear understanding and consideration of context-specific urban issues such as market fires and floods [

22]. As such, risk tends to accumulate in the absence of capacity and training on urban challenges and lack of clarity on roles and responsibilities.

A further major constraint to disaster risk governance is that there are no locally held systematic records on urban disasters and losses for Karonga Town. The available district level data on urban disasters mainly covers large intensive disaster episodes such as earth quakes and large-scale floods. Systematic records for more localised disaster data across a broad spectrum of risks experienced in Karonga and other urban centres are either inadequate or non-existent. Some health records are available from the district hospital serving the wider region, but these require detailed analysis to extract the town-specific disease burdens, trends and vulnerabilities from the records of patients living in the town. Moreover, when disaster records are in place, these are often inadequately accounted for. For example, Karonga Town registered the largest number of disasters in Malawi between 1946 and 2008, which although accounted for in district and other available data sets, is not well recognised in planning or policy [

25].

More systematic disaggregated data at the sub-district level on social demographics and disaster losses (especially from extensive and everyday risks) is necessary for effective local policy formulation and planning.

Following extensive flooding in southern Malawi in January 2015, national and international development partners have committed to assisting the country in its response strategy. However, this was subject to a conducive policy framework being in place. As such, Malawi published its Disaster Risk Management Policy (DRM) in 2015 following significant pressure from national and international development partners and donors. The approval of the policy helped to unlock considerable donor funding. For example, the World Bank committed over

$40 million for the Malawi Flood Emergency Recovery Programme (MFERP) [

26]. This situation does not reflect a one-off event, but rather exemplifies the nature of policy and practice of urban planning in Malawi and indeed many cities in sSA, which are largely influenced by external agents. The policy assigns a crucial role to decentralised governance structures from village through district to the national levels for disaster risk reduction efforts. However, the policy has some notable weaknesses that are limiting effective implementation. For instance, Malawi’s urban areas are not specifically addressed despite the increasing trend of urban disasters such as flooding and resource allocation to lower governance scales being highly inadequate [

24]. Furthermore, the disaster management structures included in the Disaster Risk Management Policy exist largely only on paper with limited capacity and practical knowledge for addressing risks and risk accumulation.

The respective priorities of donors including external governments, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and development agencies, as well as the national government all play a significant role in shaping DRM agendas at all scales. The Malawi Government has received major loans from multiple international agencies such as the African Development Bank (AfDB) and World Bank (WB), which are used for various development initiatives that have co-benefits for addressing disaster risks, such as sanitary facilities and drainage infrastructure provision. Yet, these loans have created large-scale debts. As a result, new alternative partnership arrangements are increasingly being established between the private sector, public utilities, micro-finance institutions and NGOs to support local governments in providing essential infrastructure and services [

26].

The implementation of policy in Karonga Town tends to be externally driven in terms of funding and capacity building. The national government acts both to direct policy and support implementation. Policy directives are usually given from the central to local levels. Policy implementation tends to focus on response to disaster events such as the distribution of relief items to those communities living in risk zones. Very little attempt is made to proactively reduce risks either through capacity building or infrastructure upgrading. The risk reduction efforts that are in place such as for flooding and fires are largely a result of donor contributions. Moreover, local communities perceive civil society actors as the key policy agents and collaborate with them often instead of their local governments [

22].

Transparency is embedded in the DRM policy through its provisions for accountability within decentralised governance systems. However, in practice the decentralised accountability ladder from the national level through to community levels is disconnected and fragmented. Accountability occurs separately between state actors on the one hand and between community groups and their traditional leaders on the other, with both channels experiencing challenges and conflicts. City officials are mandated to report to national policy makers. Accountability at the city level is expected through the ward councillors, but there are no such wards in place in the case of Karonga Town [

8]. Instead, ward councillors report to the citizens through traditional leaders. NGOs who have presence in the community play an intermediate or bridging role and participate in the local government meetings through the District Executive Committees (DEC). Sometimes, the DEC meetings are directly funded by the NGOs. This points to the ongoing prominent influence that NGOs have in shaping policy and practice under conditions of funding constraints faced by local governments for developing and implementing policy and democratic decision making. The independence of the DECs is essential for community-led prioritisation of issues, but there is the risk that NGOs could be setting and monopolising the development agenda and compromising the mandate of legally constituted participation spaces.

The 2015 DRM policy provides for interaction between communities and Councils through the decentralised reporting mechanism. Under this mechanism, the lowest level is the village DRM committee, followed by the Area DRM, the District DRM Committee and the National Platform at the highest level. This policy provision is a replica of the Decentralisation Policy of 1998 which seeks to entrench democracy in policy and decision-making. In practice, these committees do not have a specific urban focus. As noted, rural (Village) committees are in place in Karonga Town due to the local government dissolution in 2009. However, even in other towns and cities, such as Mzuzu City (also a small urban centre with a population of under 200,000 in Northern Malawi), where the local government exists, only city-wide DRM-Committees (counterpart of District DRM) have been established. In such cases, there are no designated officials or actors for direct policy or local community engagement at the sub-city level. Recognising this gap, Urban ARK team members based at Mzuzu University, recruited a team of Community (research) Counterparts in 2015 to provide such an interface between the local government and community. This interface has demonstrated considerable potential for meaningful collaboration between local government, community members and researchers and for supporting an informed and organised citizenry at minimal cost. In Mzuzu, the Urban ARK team based at Mzuzu University went as far as establishing the DRM Committee in one neighbourhood (in the Zolozolo West Ward) on behalf of the local government, both to create an entry point for the research but also to support a governance structure provided for by the DRM Policy. The DRM Committee has now become the locus of interaction between the city and community with the potential for upscaling citywide. The DRM Committee meets on a regular basis and is a significant platform for interaction and information sharing between researchers, local government representatives and community members. Recently established local Community Hubs under Urban ARK offer further potential for supporting effective risk sensitive development. Decentralised Community Hubs have been established in Karonga, Malawi (as well as Freetown, Sierra Leone) in partnership with local partners Mzuzu University, Malawi and Sierra Leone Urban Research Centre (SLURC) in Freetown who co-ordinate and lead the Hubs. The Hubs are centres for learning and co-ordinating community actions and programmes resulting from participatory risk mapping and assessment work in the two urban centres. These Hubs have considerable societal impact as they involve a significant training element with community members on participatory risk mapping and other methods, as well as capacity building workshops.

Despite these opportunities, mainstreaming DRR for various hazards and a transition towards risk sensitive development remains a significant challenge in Karonga due to multiple interacting factors including the absence of a functional urban local government, inadequate financing, inherent failures to plan and regulate growth and silo-based approaches [

24]. Karonga’s rapid growth adds urgency to resolve these and other challenges that are limiting risk reduction and transformative development.

3.2. Ibadan, Nigeria

The city of Ibadan, the capital of Oyo State in Nigeria is the largest traditional urban centre in sub-Saharan Africa. It has one of the highest population densities in the country, with considerable annual population growth [

27]. This increasing population concentration is occurring largely in informal/unplanned areas and without a commensurate increase in critical urban infrastructure and services. Residents of Ibadan are exposed to a range of hazards and risks including windstorms, flooding, fires, communicable and infectious diseases, road accidents and violent crime [

27,

28]. The management of risk in Ibadan is to a large extent guided by the National Disaster Management Framework (2010), together with the priorities, capacities and resources available to the relevant state government ministries and agencies, civil society organisations and development partners. A National Policy on Disaster Risk Reduction (2017) was only recently formulated. The policy recommends that disaster management in the country must be government-led and co-ordinated, have a multi-agency approach and incorporate development partners, CSOs and NGOs. The policy has also highlighted co-ordination of disaster risk reduction initiatives within a unified policy framework in a proactive manner at all levels of Government, yet implementation remains weak and fragmented [

20].

As a discrete policy area, the portfolio of risk management in the city is undertaken by the Oyo State Emergency Management Agency (OYSEMA). The activities of the Agency are governed by the National Disaster Management Framework (2010) which mandates all State Emergency Agencies in Nigeria to prepare for, prevent, mitigate, respond to, and recover from disaster events. This also includes collating data on disaster events. However, OYSEMA has functioned largely in a reactive capacity and as a co-ordinating agency during small or large-scale disaster events. In this regard, OYSEMA collaborates with the National Emergency Management Agency, State Ministry of Environment and Water Resources, Fire Service, Federal Road Safety Corps (FRSC), security agencies and Nigeria Red Cross Society. The Agency is the co-ordinating body for flood emergency situations (State Law 2008, Gazette, Vol. 34 No. 4, 19 February 2009). However, the ruling government largely determines how the agency functions. While the law that established OYSEMA requires each of the 11 Local Government Areas in the city to establish Local Emergency Management Committees (LEMCs) to mainstream disaster risk reduction activities citywide, Olaniyan et al.’s (2018) study found that the level of compliance has been extremely poor and that these LEMCs are largely non-existent. This is due to inadequate funding mechanisms, weak local government and unstable political systems [

21].

A state platform for Disaster Risk Reduction comprising stakeholders from state government ministries and agencies, faith based organisations, NGOs/CSOs and CBOs was inaugurated in 2008 to formulate policy towards disaster risk reduction in the state and by extension the city. Nonetheless, this is yet to be actualised and there is still no policy to integrate risk reduction into development planning. However, an emergency response/contingency plan has been recently developed (OYSEMA, 2013). Overall, attempts to manage everyday and other risks in the city are pursued through several channels. State ministries, departments and agencies (e.g., bureau of physical planning and development control, health, environment and water resources, Nigeria Security and Civil Defence Corps, Department of Fire Service) have a central responsibility for disaster risk management. Nevertheless, the degree to which this is achieved varies from one ministry/agency to another depending on financing and capacity. The ministry of health, for example, has different programs supported by international donors which aid to address public health risks (e.g., malaria, tuberculosis), yet there is a significant lack of mainstreaming and co-ordination of interventions across sectors for linked DRR efforts.

NGOs and civil society organisations also play a key role in addressing disaster risks across the city. For example, the Nigeria Red Cross Society (NRCS) was established in 1960 by an act of parliament with the mandate to provide physical and psychological assistance to citizens, especially during disasters. The NRCS is a major collaborator with the city government particularly regarding emergency response. The NRCS conducts preliminary risk assessments of sites and locations prone to disasters in the city and leads community sensitisation measures to support disaster prevention and preparedness. Funding received from donors is also deployed to facilitate the activities of Red Cross volunteers which contribute to addressing gaps in risk governance. The effectiveness of the NCRS in carrying out its statutory responsibility of preventing and managing disasters in the city is significantly influenced by the support received from the state government and other international and local donor agencies. Support from government has dwindled over the years and is especially dependent on the disposition of the governor at any given period.

Major risk management-related programs undertaken by different government ministries and agencies within the city are principally informed by donor priorities and resources. This is due to low public financing, knowledge gaps and the inadequate capacity of staff in government departments. Furthermore, local governments still depend on the federal and state governments for funding. For the most part, funding decisions are influenced by complex political motives including political affiliations of local populations and loyalty of local government administrators to higher level government functionaries, among others. There is also limited inter-agency co-ordination, fragmentation and overlapping responsibilities across the various government ministries and agencies in risk management. Consequently, the city government faces considerable challenges in fulfilling its mandates, including those related to risk management.

Donors, therefore, play a major role in determining risks that receive attention and the extent to which these are addressed. An on-going example is the first deliberate engagement in city-wide flood risk management; the Ibadan Urban Flood Management Project (IUFMP). This was formed at the recommendation of the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR) following the 2011 Ibadan flood disaster which highlighted the urgent need for an urban flood risk assessment and management program. Prior to 2011, the city had experienced several flood events, including major flood disasters [

20]. The IUFMP is shaped by Pillar 2 of the World Bank’s Africa Strategy which addresses vulnerability and resilience, and the World Bank/Nigeria Country Partnership Strategy (2014–2017) climate change (resilience) agenda which is open to provide support to improving the resilience of urban centers to natural disasters (IBRD 2014). Although the State government request through the Federal government was for a credit facility to address infrastructural challenges encountered resulting from the 2011 Ibadan floods, World Bank approved the following flood risk management measures:

Assessment of flood risk in the city, planning risk reduction measures, and financing of preventive structural and non-structural measures to enhance flood preparedness (preparation of urban, drainage and solid waste master plans).

Financing public infrastructure investments for flood mitigation and drainage improvements.

Improvement of institutional co-ordination on flood risk management in Ibadan.

Whereas the State government identified 48 river canals in need of dredging and widening for effective run-off discharges, only 36 were approved for funding by the World Bank. Forty other communities of flood-prone areas which did not benefit from the donor support of dredging rivers continue to advocate the government for assistance in this regard. Similarly, the inability of the government to successfully address the considerably low coverage of water supply and sanitation in the city is being aided by the African Development Bank Urban Water Supply and Sanitation Project for the city. However, the project covers only the high density residential areas and peri-urban parts of the city. Evidently, flood risk management has received much attention relative to other disaster risks and everyday hazards (e.g., fire hazards, violence, crime and road traffic accidents) because these have not acquired the status of large scale disasters or do not fall under the funding priorities of international development and donor agencies. Nonetheless, the cumulative impacts of such events are overwhelming [

27].

Risk data collection and storage remain persistently poor in Ibadan, as in other Nigerian cities. City data for all purposes (social and economic), where available, is mainly provided at the level of LGAs. Non-availability of housing and population census data at lower levels (i.e., wards and localities) remains a significant challenge for vulnerability and risk assessment for the city. Inventory of risk-related events across the city is poor and mainly limited to events with significant impacts. There is also the issue of incomplete and sporadic record keeping of risk-related data by the government and relevant city agents. Monitoring is neither regular nor systematic and is mainly undertaken for a specific need rather than on a routine basis. Manual record keeping by city government is also prone to loss or misplacement. The lack of city-wide risk data covering the whole spectrum of risks is a key limitation to informed decision making for risk management and development planning. To address this gap, the Urban ARK Ibadan city programme has systematically worked to collect city-wide data on everyday risks, and small and large disasters at the ward level for the city using multiple methods including the DesInventar methodology and household/community level assessment and understanding of urban risks through engagements/consultations with public agents (city officials), household surveys and focus group discussions with community members. The development of risk maps at the ward scale based on analysis of this data have the potential to be used as decision support tools for city authorities.

Community Development Associations (CDAs) are involved in risk management in the city through various self-help activities within wards and localities (e.g., infrastructural development, management and maintenance of roads, water supply, purchase and repair of electricity transformers, sanitation, flood and erosion control, and security enforcement). Community members also play a role in the monitoring and enforcement of regulations and guidelines geared towards risk reduction e.g., not building on flood plains and the prohibition of dumping of solid waste in drainage channels. Communities are also increasingly engaged in disaster rescue missions and disaster risk reduction activities. For example, traditional rulers, community leaders and leaders of CDAs and CBOs (e.g., market associations) have been actively engaged in stakeholders’ meetings during deliberation on risk issues (e.g., Ibadan Urban Flood Management Project stakeholders’ meetings). However, collective influence is more constrained and not at the same scale as in the case of Nairobi discussed above, for example, where there is a very strong federation presence that supports advocacy and influence of organised civil society at scale.

The Urban ARK Ibadan city programme has deliberately initiated the process for enabling risk transitions in the city by organising stakeholder meetings which have brought together community leaders, trade associations, city officials, NGOs, CSOs and researchers in group discussions including the Urban ARK city project inception/launch workshop (2015), working group sessions and meetings of the Urban ARK Stakeholders’ Platform on Risk Reduction in Ibadan (2018). These forums have enabled the collaborative identification of stresses facing the city and the key everyday hazards and disasters (shocks) from the wide spectrum of risks. The primary goal of the Stakeholders’ Platform on Risk Reduction which adopts a multi-staged process, is to develop a co-ordinated plan of action for risk reduction in the city, highlighting the most appropriate actions, responsible actors and roles for identified and prioritised risks based on the knowledge gained in the risk assessment process and local context. This is a considerable opportunity for supporting transition in the risk development nexus in Ibadan and has been strongly supported by stakeholders. But the initiative will require ongoing advocacy, engagement and support in an already constrained institutional environment as described above.

3.3. Nairobi, Kenya

Nairobi is a large and rapidly growing city; the second largest in the East Africa region, with considerable regional economic and political significance. The majority of Nairobi’s over 3.3 million population live in informal/unplanned areas, typically densely populated, low lying and flood prone with very limited basic services and infrastructure. Poverty, food insecurity and other environmental vulnerabilities are widespread. These challenges are compounded by multiple interacting shocks and stressors such as disease outbreaks. Nairobi’s social, political and physical environments are characterised by vast inequalities and injustices [

29]. Rapid, fragmented and unplanned urbanisation has led to increased flood risk across the city. Weak governance and consequent poor service delivery have exacerbated man-made hazards such as poor solid waste management, resulting in widespread unsafe disposal, with significant negative health impacts, including the proliferation of infectious and non-communicable diseases, environmental degradation and greenhouse gas emissions [

30]. This is typified by the Dandora municipal open dumpsite located close to public institutions, posing a range of health risks to the over 250,000 people estimated to be living adjacent to the site, in addition to causing extensive environmental damage [

31].

Effective urban planning has proven a major challenge in the city. As Myers [

29] (p. 44) explains “urban environmental planning in Nairobi has often been ambitious, but financially and politically unworkable”. As such, the risk-development nexus; the complex interlinkages and gaps between risk management and development, is underpinned by competing demands, resource constraints and inadequate capacity of local government. To further characterise the risk-development nexus: “the way in which urban growth and expansion are planned and managed is what largely determines the extent and distribution of risk” [

13] (p. 37). Climate risks and vulnerabilities are increasingly well recognised in the city, with several recent developments such as the Rockefeller 100 Resilient City status providing some impetus. There is considerable awareness and increasing willingness for change among key city actors including risk managers and urban planners [

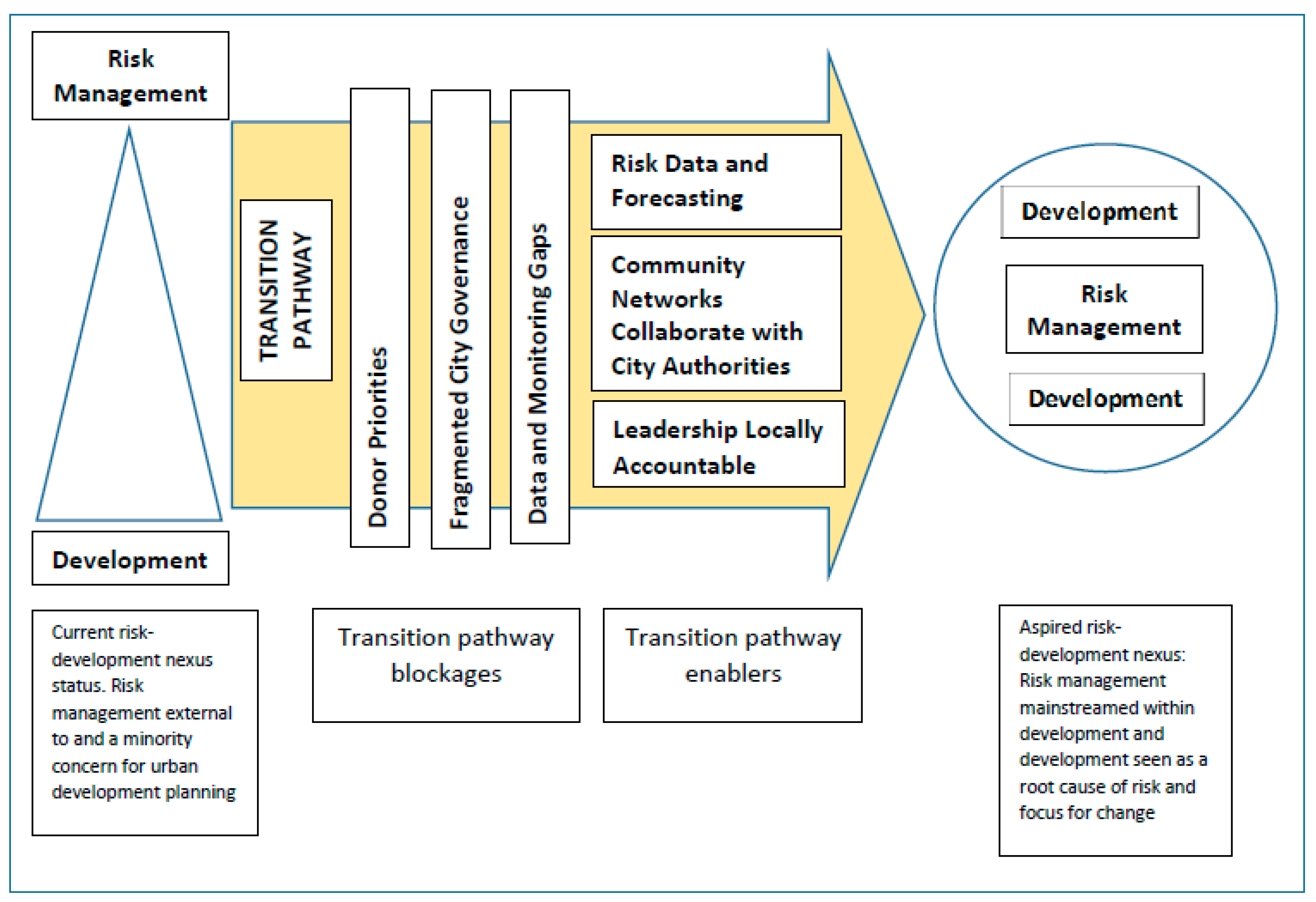

5]. However, as with many other sSA contexts, risk management remains limited and constrained by weak co-ordination between all sectors and scales of governance, as well as complex policy landscapes where implementation and enforcement are widely lacking. There is also a need to better understand interactions and cascading effects between different hazard and risk types in Nairobi and their potential effect on infrastructure and development. The tensions between formal and informal planning systems and governance arrangements also require urgent attention, particularly due to the vast extent of unplanned settlements in the city. Key additional challenges for transition in risk management include fragmented civil society, ongoing tensions between diverse city actors and hierarchical decision-making that overlooks local risk management priorities and addresses everyday development failures.

Disaster risk management in Nairobi is highly complex and cross-cutting, with an ongoing lack of clarity in roles and responsibilities within the devolved governance structure. The devolved system of governance in Kenya came into effect in 2010 when the new Constitution of Kenya (CoK, 2010) was adopted and shifted away from a centralised system. Under the Constitution there are two overarching levels of governance—National and County government. These are created on an equal basis—they are distinct but are required to work in harmony [

32]. They also have the power to secure resources, control their own budgets and raise revenues. Nairobi City County (NCC) is further devolved into sub-county, ward and village levels. Within this formal structure, the chieftancy plays a key role (albeit informally and contested in many cases) in linking communities with the lowest level of government, particularly in informal settlements which are often divided according to tribal affiliation [

33]. The sub counties and wards are the focal points of service delivery. The devolved system of governance has proved complex with ongoing challenges, fragmentation and conflicts across all governance scales. The Constitution recognises disaster risk management as a developmental challenge that should be addressed through both county and national government levels, as well as local levels [

34]. A Draft National Policy of Disaster Management (DRM Policy, 2009) was formulated in 2009 with the intention of clearly identifying institutional mechanisms and responsibilities for DRR and unifying existing ad hoc policies relating to DRM in the country. However, almost a decade later this is still awaiting cabinet approval and thus co-ordination challenges remain across all levels as well as continued ambiguity over mandates and responsibilities. A further constraint on DRR in Kenya is that the national budget priorities continue to focus on disaster relief and poster-disaster response [

34]. In the absence of an overarching national policy, Nairobi County enacted a disaster management and firefighting policy in 2015, which has created some clarity in DRR mechanisms, but implementation has proved challenging to date.

Transition pathways are evidenced in emergent innovative and inclusive approaches to governance and development, with risk reduction co-benefits and opportunities beginning to transpire across the city. This is increasingly occurring through the collective actions of networked civil society, often in collaboration with local government and other actors. Particularly notable leadership has been through organised community associations opening opportunities for transition. For example, the Kenyan slum-dweller federation Muungano wa Wanavijiji led a mobilisation and advocacy campaign, with technical assistance from Akiba Mashinani Trust (AMT) and staff at SDI-Kenya (SDI-K), which led to the designation of the Mukuru informal settlement Special Planning Area (SPA). The Nairobi City County designated the SPA in August 2017. Interdisciplinary consortia including academic, government, private-sector, and civil society actors have synthesised data and generated policy briefs to inform planning strategies. In support of widespread participation in these planning strategies and due to the SPA’s scale and complexity, Muungano has adopted innovative approaches to mobilise residents and collecting data, which have benefited from Urban-ARK support. Planning for the SPA will also help integrate risk management into securing land tenure and upgrading, and the redevelopment schemes through innovative multi-level governance and connecting community members across all levels of government. While the initiative is still in its early stages and many challenges remain, this is a notable transition in state-civil society relations in Nairobi and could serve as a catalyst for governance reform in other urban centres across sSA.

Additional innovation and potential for transition is evidenced at ward and local community scales where actors have taken advantage of existing structures to strengthen DRM and DRR. For example, at the local level, District Steering Committees have also assumed the role of Disaster Committees and in the absence of dedicated funding mechanisms for DRM at community scales, alternative sources are being drawn on to support DRR such as the Youth Enterprise Development Fund and the Women Development Fund [

25]. A key challenge is ensuring that such innovative initiatives are recognised and supported as devolution continues to be implemented and DRM policy is approved. These initiatives are often cross-cutting and fall under broader development programmes, such as slum upgrading projects. Based on their research on slum upgrading in Kibera, Nairobi for Urban ARK; Mitra et al. [

33] explain that such integrative approaches can become an important tool for strengthening resilience to risks such as flooding, conflict, and security through building trust between communities, government and other actors. They argue that “development interventions adopting an integrated, multi-sector, consultative approach have a stronger potential to increase resilience in multi-risk environments compared to single sector projects” [

33] (p. 4).

Disaster risk governance in Nairobi is constrained by inadequate systematic data on everyday and large-scale disasters available in appropriate and accessible formats for all stakeholders, including practitioners and local communities. However, findings from Urban ARK research in Nairobi and other cities such as Freetown, Sierra Leone have highlighted the considerable potential and importance of drawing on detailed risk data collected by organised civil society through community profiling and mapping for identifying and acting on disaster risk [

35,

36]. For example, SDI have prepared detailed profiles and maps of informal settlements in Nairobi and use this information for supporting state engagement, which fills a large data gap at local government level. This has been a major factor in supporting the development of the SPA discussed above.

There is further opportunity for addressing the disaster risk data challenge through drawing on longstanding local data collection initiatives on risks, broader urbanisation processes, urban health and wellbeing statistics, especially for informal settlements in the city. These initiatives have been led by local, national and international research institutes such as the African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC) through the Nairobi Urban Health and Demographic Surveillance System (NUDHSS) from 2002 to date and the Nairobi Cross-sectional Slum Surveys in 2000 and 2012. These significant data sets and related research studies can support implementing agencies and local governments to identify priority risk areas across the city and support effective risk reduction and service delivery models [

37].

In further recognition of the need to address fragmentation in DRM across Nairobi and to support integration across diverse actors, there have been recent calls from city actors, particularly the Nairobi City County to develop a shared platform for information sharing and collaboration. Significantly, the Nairobi Urban Risk Partnership was proposed at an exploratory meeting initiated and facilitated by Urban ARK at the African Population and Health Research Centre (APHRC), on 10 May 2017. This was in response to an identified need to address a major gap and need in the city for driving forward the disaster risk and resilience agenda and building a community of practice. The partnership was proposed by the City County Urban Planning Department and seconded by Departments of Security and Disaster Management, Housing and Urban Renewal, and the University of Nairobi. The partnership brings together stakeholders leading various urban risk efforts in the city and aims to ultimately inform the development of an urban risk management plan, pursuant to the Nairobi City County Disaster and Emergency Management Act (2015). A further aim is to mainstream disaster risk management planning in normative programs. There are many development actors that have influence development and risk agendas in the city including international donors and aid organisations, private sector, CBOs and NGOs, yet often these efforts are fragmented with considerable duplication of efforts. As such, the partnership is a useful central co-ordination body and information source for external funders and donors undertaking research and development interventions in the city. Overall, the partnership holds considerable potential for strengthening DRR and DRM in the city and improving co-ordination; however, sustained momentum is constrained by local government transition, competing political priorities and budget constraints. To help overcome this, a designated Nairobi-based partnership co-ordinator has been assigned and terms of reference have been drawn up by the NCC for facilitating partnership activities.

3.4. Niamey, Niger

Niamey is the state capital of Niger and has grown from 30,000 inhabitants in 1960 to over 1 million in 2012 [

38]. It is one of the poorest cities in sSA and is growing rapidly with immigration from drought-prone rural districts characterised by widespread poverty and food insecurity [

39]. Niamey is a multi-ethnic city, with seasonal and permanent migrants from across Niger, as well as nationals from neighbouring countries, Nigeria, Mali and Benin. Traditional livelihoods of agro-pastoralism have largely given way to the informal small-scale service sector income-generating activities in which the poor generally work. The city is facing increasing risks, principally flooding, public health issues and disease, as well as food insecurity [

39]. These risks are exacerbated by widespread economic precariousness, increasing unemployment, delinquency, school dropouts and conflict in neighbouring countries. Poor land use planning and limited and weak infrastructure combined with mounting population pressure, principally due to rural–urban migration, have resulted in the increased occupation of flood-prone areas [

39]. Many new migrants occupy sites that are vulnerable to flooding [

39,

40]. The associated risks are exacerbated by the variability and extremity of Africa’s changing climate [

41].

With a significant proportion of the city’s population living in unplanned settlements and marginal land, the State of Niger has adopted a housing policy and sanctions to regulate development in an attempt to provide improved and adequate housing across the country. Several legislative and regulatory measures have been introduced (e.g., Law 2017-20 of 12 April 2017) to prohibit construction in risky areas and to establish related planning and operational planning procedures. However, implementation has been weak with continued unprecedented development of informal building and other practices that have exacerbated vulnerabilities across the urban risk landscape. While the original spatial extension from founding villages followed a planned layout, the liberalisation of the land market from 1997 onwards, combined with the lack of monitoring and control amplified informal practices regarding both access to land and building construction. Informal settlements and non-permanent traditional habitats have proliferated throughout the city, largely through informal or illegal subdivision of plots by traditional landholders. The city’s risk landscape has been strongly shaped and exacerbated by these patterns and approaches to development.

Urban governance is shared between the state, local and regional authorities, traditional rulers, donors, and NGOs who often intervene in specific sectors (health, education, hygiene and sanitation); however, there is limited co-ordination and collaboration between these actors. Since 2000, Niamey has experienced an ongoing political decentralisation process, yet functions and responsibilities between local government, chiefs and central government at the local scale remain unclear with considerable overlap. The considerable instability and high staff turnover within the city leadership and other governmental levels has led to weak co-ordination and implementation of risk-related and development-related interventions. This fragmentation in governance results in a lack of accountability and monitoring of actions. The state is responsible for monitoring all risk and development-related projects, programmes and investments over the long-term or regulating the implementing organisation to undertake these actions. However, the state lacks resources to do this, and consequently, monitoring and evaluation of such initiatives are weak. A relevant example is the case of a recent large scale cadastral survey undertaken in Niamey by Agence Française de Développement. The operation came to a halt when the agency withdrew after the project duration with very little impact and the city continues to experience considerable and often unregulated expansion without considering the outcomes of the survey.

In most development projects and programmes, Niger relies heavily on the support of donors whose priorities often do not fundamentally align with urban dwellers’ concerns. For example, while roads and sanitation are the major problems in the city, donors’ principal interventions have been to finance the cadastral survey and draw up an urban plan. Yet, these cost-intensive operations have had little practical impact or developmental benefit, particularly due to the short-term nature of funding availability and lack of continued support for implementation and monitoring. Risk management capacity in Niamey is low with local authorities often depending on external aid and humanitarian structures to respond to emergencies. There are several major internationally funded programmes underway to address acute risks of food insecurity, floods and other issues. The most relevant example is the World Bank-funded Niger Disaster Risk Management and Urban Development Project [

42] that includes flood risk management investments such as drainage, irrigation, dike construction and flood protection infrastructure, as well as the rehabilitation of watersheds in urban and rural areas, and capacity building for urban development and disaster risk management. Furthermore, to address food insecurity, the National Food Crisis Prevention and Management System has been created with supporting bodies such as the Co-ordination Unit of the Early Warning System and the Food Crisis Unit, all funded by multiple donors. However, there is poor co-ordination and communication between the donor funded initiatives and other initiatives described, with duplication of efforts and lack of monitoring remaining commonplace.

In recent years, there has been growing research attention on urban risks and strategies for their prevention in Niamey. For example, Urban ARK researchers from Abdou Moumouni University undertook an adapted household economy baseline study of vulnerability to flooding, as well as an inventory of small-scale disasters using DesInventar [

40]. The Network on Hydrometeorological Risks in African cities (RHYVA) has also undertaken extensive studies on the causes of flooding in Niamey. Research centres such as the Agro-Hydrometeorological Centre (Agrhymet) and the African Centre for Applications of Meteorology for Development (ACMAD); the Niger Basin Authority (NBA) have also carried out work on the risks that led to the production of the very first river flood risk maps in the city of Niamey. Evidently, data on disaster risks, particularly flooding, does exist to some extent but there is a reluctance amongst many institutions to co-ordinate and consolidate data and make data openly accessible. For example, there is no standardised flood loss database for Niamey, yet multiple isolated individual studies indicate a dramatic increase in the frequency and intensity of floods observed in the city over the last decade [

40,

43]. The state has failed to ensure co-ordination and to support open access data, despite the importance of this for facilitating increased understanding among diverse stakeholders of a range of risks faced by the city and how they are changing. However, the recent creation of a ministry in charge of disasters and humanitarian action signals potential for greater co-ordination and improved risk prevention and disaster management in the city of Niamey.

At the neighbourhood-level, communities are increasingly self-organising and engaging with local authorities to help address local development and risk-related challenges. The most noteworthy actions are those of women’s and young people’s groups that are involved in addressing hygiene and sanitation issues. These activities are carried out under the patronage of the neighbourhood chiefs who are considered as local representatives of the administration. However, these activities are often undertaken on an ad hoc and unco-ordinated basis, with limited influence at scale. Community cohesion has also been facilitated by the establishment of security brigades in the different districts, which has helped to reduce theft and crime. Greater collaboration between the state and local communities would help to support disaster risk reduction across the city [

44]. As Revi et al. [

12] (p. 28) emphasise, it is critical to focus on and understand how linkages are established between local governments, community organisations, researchers and other urban actors in defining and then driving alternative forms of risk reduction, and that this “depends on city governments that can listen to citizen movements and see the validity of the living alternatives they offer”.

Overall, risk reduction in Niamey is constrained by several key factors: Donors’ priorities do not align with local priorities; urban governance is highly fragmented with unclear and sometimes conflicting roles and responsibilities between actors; data sets relating to flooding and other risks are fragmented, incomplete and sometimes contradictory with open access remaining a challenge; and monitoring and evaluation of risk-related interventions remains weak. The chronic instability and high turnover of senior municipal officials results in a lack of continuity in risk and development interventions and priorities. The overall lack of synergies described severely limits efforts to identify and manage risks effectively. These constraints notwithstanding, there is opportunity for movement towards transition and transformation in risk management and development through recent progressive policies and initiatives such as the creation of the Ministry for Disasters and Humanitarian Action and Risk and Disaster Management Program, as well as increasingly active self-organised community groups that are addressing key disaster issues at neighbourhood scales and lobbying the government.