1. Introduction

Industrial clusters have received increasing attention from many scholars over the last decades. It is generally stated that this territorial agglomeration of firms brings important advantages to their companies in terms of knowledge flows [

1]. In this sense, the literature has highlighted the capacity of their firms to create and disseminate knowledge and, consequently, to enhance their performance [

2].

In line with a number of studies that have begun to emphasize the importance that each firm has in the cluster knowledge dissemination and acquisition processes and similarly the importance that in-situ institutions have in the cluster by going for the knowledge dissemination by the formation of “inter-firm networking” [

3,

4,

5,

6], this study focuses on the manner in which intra-cluster relations can improve the international presence of cluster firms.

Most of the preceding theoretical background has been seriously analysed and practically assessed in contexts of mature industrial clusters in well-established economies [

7]. However, the analysis of the influence of inter-organizational networks in environments such as emerging clusters in transition economies are scarcer, not being a major area of research compared to other analyses carried out in more developed countries and mature clusters. On the other hand, the way of transmitting the knowledge inside the cluster was intensely studied and approached from several perspectives [

3,

4,

5,

6], but the relationship between cluster linkages and international presence of cluster firms remains an unresolved issue.

With the aim of filling these gaps and contributing to the debate on the role of inter-organizational networks in cluster contexts, this research is aimed at analysing the presence, structure, and influence of collaborative networks on internationalization processes in contexts of emerging clusters in transition economies. In these territorial agglomerations, which in a temporary continuum are in the early stages of their life cycle, the lack of trust and maturity of inter-organizational relationships may not create the right context for the exchange of knowledge flows between their companies. Therefore, we consider it important to contribute to the literature by providing new empirical evidence in these environments on the presence and role of inter-organizational relationships.

In order to proceed with the research, we conducted an empirical analysis using data collected in the Muntenia-Oltenia wine cluster, located in one of the most appreciated wine regions in Romania. This cluster is made up of 42 wineries and can be considered to be in an early stage of its life cycle. It is worth noting that this sector is traditionally not very innovative in technical terms, and also, in an economy in transition, elements such as internationalisation play a priority role. So, this new context invites us to study in detail whether the effects and conclusions raised by the traditional and above-mentioned literature are also reproducible here.

The results reveal the presence of a solid balanced structure of knowledge relationships between the wineries in the cluster, even in the initial stages of its life cycle. Findings also suggest that these relations play a relevant role in the international presence of cluster firms. Similarly, our findings reveal a relationship between the connectedness with trade support institutions and the access to international markets. These results, in line with previous research, help to approximate the relevance of knowledge flows in cluster contexts. But, unlike past contributions, they allow us to analyse this influence in contexts of internationalization processes in young clusters of emerging economies. It is important to note that these results can provide insights for firms, institutions, and policymakers about how to promote cluster firms’ international presence.

The paper is structured as follows. After the introduction,

Section 2 provides a review of the literature and defines the research questions. Further on,

Section 3 describes the empirical setting, methods, data, and measures used in this research.

Section 4 shows the empirical evidence and discusses the results and, finally,

Section 5 concludes the paper and presents the limitations of this study.

2. Literature Review and Research Questions

Industrial clusters can be characterized as a system of inter-organizational relations among various partners, such as customers, competitors, suppliers, and institutions [

8], where geographical closeness and a powerful sense of belonging are the main aspects favouring such relations that rely on values such as confidence and reciprocation [

9].

In general, the establishment of links between cluster firms has been used to explain the emergence of localised knowledge flows and transfers [

10]. According to Maskell [

11], in clusters, the possibility to access information and knowledge is said to be chancy and it is often caused by geographical proximity and by the fact that the various participants (i.e., entrepreneurs, technicians, workers, etc.) share the same cultural values, the same codes for communication, and the same models of behaviour. In line with this view, less formal meetings would permit information to be shared by cluster members, whereas the others are excluded, given the fact that they are not part of the local community.

In regional clusters, local ties are typically high value in terms of quality of knowledge due to the fact that, on the one hand, the geographical proximity of the managers and workers offers them the possibility to meet face to face in order to solve different uncertain problems, and on the other hand, as they operate in similar environments, they are likely to face context-specific problems, being at the same time more capable to solve them because they have the necessary experience [

7].

For years, scholars have considered that the greater access to knowledge resources that cluster firms have by the mere fact of being geographically close has allowed them to exploit competitive advantages that were not available in other contexts. Under these premises, it has generally been highlighted that clustered firms show higher capabilities than isolated firms [

12]. In the same way, Baptista and Swann [

13] claim that a firm is more likely to innovate if it is situated in a region where there is a massive presence of the firms from the same industry, since intra-cluster learning is considered as the driver of innovative performance [

14]. Complementarily, Baptista [

15] highlights the fact that the existence of a significant positive regional learning effect influencing diffusion indicates that the geographical proximity facilitates the transmission of technology from the firms that have adopted it ahead of the others.

While these theoretical premises have been maintained for years, some researchers have recently begun to support the idea that geographical proximity is not sufficient per se in order to explain the process of localized learning and innovation, but rather the way in which companies integrate into the cluster knowledge networks [

16]. Thus, knowledge does not flow freely throughout the cluster, but through networks configured on the basis of the particular decisions of their companies. In this way, the market and social-institutional relations become important vehicles for knowledge diffusion at the intra-cluster level. Morgan [

17] considers that the existence of stable and intense customer-supplier relationships is essential for the exchange of information. Similarly, the movement of the workforce inside the borders of the cluster contributes to the transfer of knowledge and of the local know-how [

18].

In sum, all these contributions have started to put the company at the centre of cluster research, highlighting the primary role that an individual firm has in the cluster knowledge diffusion and learning processes. Therefore, it is not the territory that is self-organising, but the firms’ decision-making process which shapes and influences its development [

19].

In line with the above, most recent research has focused on the application of social network analysis techniques to study the morphology and configuration of cluster networks and how the integration of cluster firms into them influences their performance. Thus, diverse studies indicate that the centrality in the cluster knowledge network, i.e., the firm connectedness to the cluster network, has a positive effect on the firm’s innovative performance [

3,

4,

5,

6]. In short, depending on the way in which a company integrates into such networks, the knowledge received and shared may vary, and therefore also the benefits obtained from such knowledge sharing.

Complementarily to inter-firm relationships, other authors have highlighted the important role that local institutions play in the cluster by favouring the diffusion of knowledge through the creation of “inter-firm networking” [

20]. In this sense, local institutions offer trained information, working as a bridge between firms’ knowledge basis and the larger knowledge basis of the economy. Local institutions, therefore, have a vital role in the creation and sale of new products, techniques, and services [

21]. These organisations contain R&D services; consulting activities; and monetary, professional, and coaching services, etc. In the context of emerging clusters, regional institutions can offer services in order to connect cluster firms with global value chains.

Most of the previous theoretical premises have been profoundly studied and empirically evaluated in contexts of mature industrial clusters in developed economies [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Although these results can be a priori generalized to other scenarios, certain situations and particularities invite us to deepen and carry out specific studies.

In this research, we focus on contexts and strategies different from those traditionally studied. Thus, in this work, we first focus our attention on clusters that are in the early stages of their life cycle. As diverse contributions suggest, the lack of trust and the low willingness to cooperate of the firms, the fragmentation and isolation of producers, and poor producer competencies caused in part by the absence of lead organizations in these territorial agglomerations, may not create the right scenario for knowledge to be exchanged between companies [

22]. In this way, collaborative networks in these contexts can be limited to small areas with an unequal distribution, especially in those clusters that are very large geographically. Therefore, the premises and conclusions obtained in contexts of mature clusters may not be valid in these scenarios.

On the other hand, in this research, we also centre our interest on clusters located in economies in transition, which have not often received the attention required by the research community. In these environments, the institutional apparatus often lacks the necessary efficiency to achieve an adequate and balanced integration of its territory [

23]. In this sense, companies may find it more difficult to find support and develop their activity than in contexts of more developed countries. As a result, the collaborative networks that may be present in these environments may a priori have neither the density nor the extent of those existing in other mature clusters of developed countries.

On the basis on the above considerations, we consider it important to conduct a preliminary study of the structure and dissemination of knowledge networks in emerging clusters of transition economies. We intend to contribute to the literature by providing new empirical evidence in these environments on the presence and role of inter-organizational relationships. To this end, we raise a first research question:

Research question 1: How are firms involved in the knowledge network of the emerging cluster? With whom are firms connected?

In contexts of clusters of transition economies, in addition to innovation, certain strategies such as access to international markets receive special attention and priority from their companies because they allow them to find markets where their products are better valued and remunerated compared to local markets [

24].

Traditional literature on clusters has not studied in depth how intra-cluster relationships can influence the international presence of cluster firms. In fact, it has often relied on a firm’s internal factors to describe it. However, as some studies indicate, it is necessary to include other variables of a more external nature that go beyond the firms’ individual characteristics in international trade models [

25]. Thus, some authors show that cooperation with other firms is an alternative mechanism used by firms to overcome resources and skill limitations [

26,

27,

28]. Additionally, it assists firms in collecting the necessary knowledge on foreign customers, it helps to adjust the product to the target market’s necessities and claims, and eventually it improves export achievement [

29]. To put it differently, by working with other firms, SMEs can reap the same benefits as big firms by taking advantage of economies of scale and reducing risks or eliminating repeated risks [

30]. Therefore, new analyses are required in cluster contexts to deepen the study of the relationship between cluster linkages and the international presence of cluster firms. For this reason, and with the goal of providing new evidence in this area, we suggest a second question to study:

Research question 2: Does firms’ cluster connectedness influence their international presence in contexts of emerging clusters in transition economies? If so, what position may be the most beneficial for increasing firms’ international presence?

As previously stated, a growing body of literature has stressed the relevant role that institutions can play in developing and improving the dissemination of knowledge within industrial clusters [

20].

In this regard, establishing links with cluster institutions can generate a double benefit for cluster companies. On the one hand, it can facilitate obtaining new knowledge from the institutions that can lead to an improvement in its competitiveness in international markets [

31]. On the other hand, it can also facilitate communication and knowledge sharing with other cluster firms, which, as seen above, can also promote the acquisition of knowledge on foreign markets, thus improving the export performance.

Based on these premises, this research also aims to deepen the role and influence of local institutions in the internationalization processes of emerging cluster companies in transition economies. The particular conditions of these contexts invite us to deepen the study of their influence. On the other hand, it is important to stress that not all relations with institutions allow the same benefits to be obtained. The type of institution and the objectives pursued by the company may determine the final benefits obtained.

Therefore, and based on the above premises, we pose a final research question:

Research question 3: Does firms’ involvement with local institutions in contexts of emerging clusters in transition economies influence their international presence? If so, what types of institutions provide the greatest benefits in these internationalization processes?

3. Research Methodology

3.1. The Muntenia-Oltenia Wine Cluster

The empirical study has drawn on the population of firms belonging to the Muntenia-Oltenia wine cluster in Romania, a region located in the Southern part of Romania which possesses the largest group of wine producers in the country.

The cluster is composed of different sized wineries and can be considered to be in the growth stage of its lifecycle. On the other hand, it is influenced by the largest presence of foreign investment.

The cluster is supported by different national and regional institutions which supervise production processes and guarantee products’ quality. They also provide technical and commercial support to wine producers. However, unexpectedly, none of them has played a leading role in the growth and modernization of the wine sector in the region.

In this sense, the most relevant institution in the cluster is ONVPV (National Office of Vine and Wine Products), which is subordinated to the Romanian Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development. Its unique role is to manage the certification process of the designation of origin (D.O.C.) and geographical indication (I.G) to the Romanian winemakers interested in producing quality wines. Apart from this function this institution does not offer any other service for Romanian winemakers.

On the other hand, Research and Development Institutes of Viticulture and Wine from Valea Calugărească, Drăgășani, and Pietrosa Buzău, state institutions, which, in the past, were the central core of growing zones, are endangered today due to underfunding and the lack of a national strategy for the development of the wine sector.

The producers are mainly commercially supported by two regional associations which are facilitating networking and communication among their members and other renowned wine associations of producers and exporters in the European Union. First, we can find APEV (The Wine Exporters and Producers Association), which comprises wine producers and exporting companies, located in almost all the Romanian winegrowing areas. The main goal of this association is helping companies reach the European Union, not only via specific market research, but also in Romanian wines promotion campaigns. Another objective is to attract foreign direct and portfolio investment in the field. Finally, we can also find APVR (Association for the Promotion of Romanian Wine), which is an interregional association that aims to support producers and exporters by identifying business opportunities and providing promotional material to members, statistical data, analyses, studies, generic wine promotion programs, and support for participation in fairs and exhibitions.

3.2. Sample and Data Collection

According to the ONVPV, the cluster in 2016 was made up of a total of 45 wineries. Therefore, this group of companies represented our initial population of study.

Our fieldwork in the Muntenia-Oltenia wine cluster was conducted during the second half of 2016. In a first stage, interviews held with two key wineries and a panel of experts from local institutions enabled us to obtain information on several aspects of the wine cluster. Also, it allowed us to build a pilot questionnaire. Once certain modifications derived from a pre-test made with our firms and members of this panel were included, the final version of our questionnaire was ready to be submitted.

The questionnaire included questions related to the type of wines produced, target markets, involvement with institutions, innovation-related processes, and performance at the firm level. Complementing this, it also included a group of questions aimed at mapping the relational activity of the wineries in the cluster. More concretely, we opted for the so-called Roster-Recall method [

32] to obtain the data to build the cluster collaborative network. Methodological considerations [

33,

34] and previous research [

35,

36,

37,

38] make this strategy extremely advisable. With this method, each firm is confronted with a complete list of the wine producers of the cluster and is asked to specify from whom they received or transferred market or technical advice. In particular, they were asked the following two questions: (a) From which of the wineries on the list have you regularly asked for technical information during the last three years? (b) From which of the wineries on the list have you regularly received requests for technical information during the last three years? On the other hand, respondents were also invited to add any other wineries with whom they had contact but did not appear on the list. Relational data were arranged in a square data matrix in which cell

ij was coded “1” when the winery

i reported a knowledge transfer to the winery

j. Thus, the relational data captured enabled a reliable reconstruction of the cluster knowledge network through directional links between the different wine producers of the cluster.

After the definition and validation of the questionnaire, in a second stage, the data collection process was carried out by the research authors through one-hour face-to-face interviews with CEOs and chief oenologists from each winery. The interviews, apart from allowing us to obtain the data from the questionnaire, made it possible to improve our understanding of some aspects of the cluster, such as wineries’ market strategies and technical developments, as well as their orientation towards innovation processes. During this data collection process, 42 cluster’s wineries agreed to collaborate, thus representing a remarkable response rate of over 93%.

The main characteristics of the sample of wineries analysed are shown in

Table 1.

3.3. Variables

The variables and the measures used to operationalize them in this research are now presented.

(1) International Presence (Ip)

This variable makes reference to the level of internationalization of the company. It is measured through the number of litres of wine sold by each winery in international markets. A logarithmic function was applied to this data in order to smooth it, as employed in other contributions such as Tsai [

39], among others.

(2) Cluster Connectedness (Cc)

This variable measures the number of connections in the cluster network developed by each winery. The greater the number of connections in the network, the greater its cluster connectedness. In order to make the Cc variable operational, we applied social network analysis (SNA) methods. They provide instruments to explore the structural properties of a network, and encompass theories, models, and applications that are expressed in terms of relational concepts or processes [

32]. It has been used in the analysis of the relationships within clusters by several authors [

35,

36,

37,

40].

(3) Involvement with Trade Support Institutions (TradeSI) and Technical Support Institutions (TechSI)

We asked firms to evaluate their involvement with collaboration agreements established with both trade support institutions and technical support institutions of the cluster. More concretely, we defined two different variables. The first one measured the number of trade support institutions of the cluster with which each winery was directly involved (TradeSI). In a similar way, we also defined a second variable which measured the number of technical support institutions of the cluster with which each winery maintained direct relationships (TechSI).

3.4. Analysis Techniques

In order to analyse the structure of the inter-firm relationships in the cluster, we applied SNA methods using the UCINET v.6 software application [

41]. In addition, to graphically depict the networks of relations, we used the NETDRAW application included in this software package and also Gephi, an open-source visualization and exploration software for all kinds of graphs and networks.

Finally, to study the differences between groups of wineries, we used non-parametric tests, as assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity were not met. For this final analysis, we used the SPSS v16 statistics software.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Research Question 1: Involvement of the Wineries and Distribution of Linkages in the Cluster Network

Figure 1 shows the knowledge network of the sample analysed. In the network, one node represents one winery, and a line between two nodes indicates the presence of a relation between them. Furthermore, the size of the nodes is associated with their degree of relational activity. In this way, the larger the size of the node, the higher their degree of interaction.

Visually, the figure reveals several important aspects of the Muntenia-Oltenia wineries’ relations. First, we can see that although the cluster is in an early stage of its life cycle, most of the firms develop knowledge relations. Furthermore, based on the previous figure, we can see that there are some wineries that are disconnected from the network. The data in

Table 2 confirms the impressions yielded from this visual inspection.

Based on the table above, we can see that the network shows remarkable levels of interaction, thus confirming that the clustered wineries significantly develop knowledge ties, with a network density of 4.24%, an average number of links per winery of 1.738, and only six isolated nodes. On the other hand, the Gini concentration index measures the degree of inequality in the distribution of links between network agents [

42]. As this index approaches 1, the number of links established by the nodes of a network is much more unequal. Conversely, a value close to zero indicates a more homogeneous distribution of the links between the different nodes of the network. Applied to our case, this index shows whether there are wineries with a higher number of contacts than others. The results obtained indicate a medium degree of heterogeneity in the number of bonds per firm. Therefore, the integration of the wineries in the cluster knowledge networks is carried out, to a certain extent, in an unequal manner. In turn, reciprocity measures the number of bonds that are reciprocal within a given network. When we have reciprocal exchanges, the bonds are much more stable and reliable. The results show that reciprocity is significantly high, with a value of 52.10%. This result shows that the network is very solid and stable, suggesting the existence of a high degree of trust between its members.

On the other hand, the literature has shown the importance of geographical proximity for the development and maintenance of inter-organisational relations [

38,

43,

44]. The Muntenia-Oltenia cluster covers a wide geographical area of southern Romania of 87,156 km

2. In this cluster, we can find three main wine sub-regions, given their size. Firstly, the West Oltenia sub-region covering the towns of Corcova, Vânju Mare, Oprișor, Băileşti, and Segarcea. Secondly, the East Oltenia sub-region, which is concentrated around Drăgășani, and finally, the Muntenia sub-region, which is located around the towns of Buzău, Mizil, Urlaţi, and Ploieşti. The distribution of the wineries between the three sub-regions is as follows (see

Table 3).

Faced with this situation and in order to describe the type of connections that wineries develop, we wonder how the cluster is internally structured and whether there are connections and links between the different wine sub-regions of the Muntenia-Oltenia region or if, on the other hand, following the pattern of other clusters, links only take place within wine sub-regions or between firms that are geographically closer. The following

Table 4 presents the number of links within and between the three wine sub-regions in the cluster network in quantitative terms.

Therefore, and based on the previous results, 43.84% of the outgoing links in the cluster knowledge network take place between different sub-regions of the cluster.

Alternatively, we have also calculated the E-I index for the network. This index is measured for a network made up of different groups through the number of ties external to the groups minus the number of ties that are internal to the groups divided by the total number of ties. This value can range from 1 to −1, taking the extreme value of 1 when all network links take place between groups and the value −1 when all network links take place within the groups. In this study, the E-I Index obtained for the knowledge network is −0.1233 (E-I index is significant at 0.05 level).

This result reveals two main findings. On the one hand, geographical proximity plays a relevant role in the configuration of the cluster relationships in the network, as suggested by the literature. Thus, links within sub-regions predominate over links between sub-regions. However, and on the other hand, despite being a geographically large cluster, it is well connected between sub-regions through knowledge relationships. Therefore, the solid links between sub-regions also play an active role in the configuration of the cluster’s relational network.

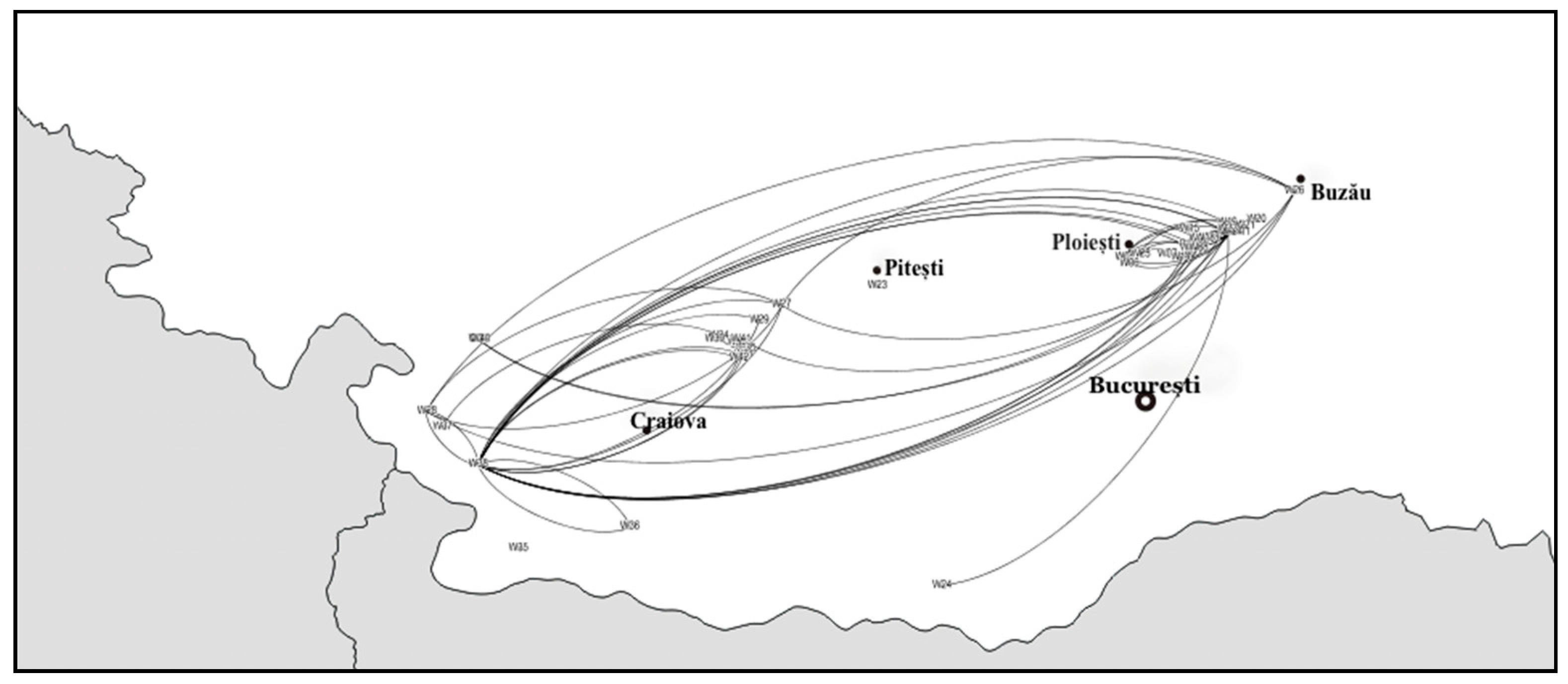

Complementing and confirming the results obtained by the quantitative data, the map below (

Figure 2) graphically shows the geographical distribution of links between the different wineries and sub-regions in the Multenia-Oltenia wine cluster for the knowledge network.

4.2. Research Question 2: Influence of the Wineries’ Cluster Connectedness on Their International Presence

The second research question analyses the relationship between the level of cluster connectedness (Cc) of the wineries and their international presence.

To proceed, we have classified the wineries in three groups of the same size (n = 14) based on their level of cluster connectedness. In this way, the first group (CcG1) will be comprised of the wineries with the lowest level of cluster connectedness (lowest tertile), that is, the wineries barely connected to or even disconnected from the wine cluster. The second group (CcG2) will include wineries with an intermediate level of connectedness (central tertile), and finally, the third group (CcG3) will be made up of the wineries with the highest level of cluster connectedness (highest tertile).

Table 5 presents the descriptive statistics of the groups. Some interesting observations appear in the table, for example, the companies in the group with the lowest level of cluster connectedness are of a small size and have less hectares of land, with no excessive differences in other characteristics being observed when compared with the rest. On the other hand, the differences between the other two groups are apparently not very significant, except that the companies with the highest level of cluster connectedness have the largest number of foreign oenologists and they are mainly concentrated in the area of Muntenia.

As commented on earlier, since ANOVA requirements cannot be met, we will proceed with the analysis by applying non-parametric tests. Concretely, we considered the application of a Kruskal-Wallis test (H) to determine whether there are significant differences among the three groups of wineries [

45]. The Kruskal-Wallis test compares three or more samples and indicates whether the distribution of at least one of them is different from the others. In case significant differences exist, we carried out an additional post-hoc analysis to specifically identify which group or groups are different from the rest. Concretely, pair-wise comparisons were performed using Dunn’s [

46] procedure with a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

The results of the Kruskal-Wallis test are shown in

Table 6. As can be observed, at least one group presents significant differences in terms of international presence. In order to examine specific differences between groups, we proceeded with a Bonferroni-Dunn post-hoc analysis. The results show that the international presence of the wineries in the third group (CcG3), that is, the wineries with higher cluster connectedness, is higher than and significantly different from the other two groups. Thus, the third group would be considered a homogeneous group. On the other hand, the mean ranks of the wineries in the first (CcG1) and second (CcG2) groups are lower and do not show statistically significant differences between them in terms of international presence, meaning that they would comprise a second homogeneous group.

4.3. Research Question 3: Influence of the Wineries’ Involvement with Local Institutions on Their International Presence

Finally, the third research question examines the relationship between the involvement of the cluster wineries with institutions and their international presence. In a more concrete way, we study this relationship separately from the point of view of the involvement with trade support institutions (TradeSI) and from the point of view of the involvement with technical support institutions (TechSI).

In the same way as in the previous research question, we have proceeded to classify companies according to their intensity in the classification variables. In this way, for the case of the relationship between the involvement of the wineries with TradeSI and their international presence, a first group (TradeSIG1) has been established that includes the wineries least involved with TradeSI (lowest tertile). Complementarily, a second group (TradeSIG2) has been defined covering wineries with a medium involvement with TradeSI (intermediate tertile). Finally, a third group (TradeSIG3) of wineries has been defined that includes those that develop more relationships with TradeSI (highest tertile). Following the same procedure as above, we have also classified the wineries into three groups according to their level of relationship with TechSI: TechSIG1, TechSIG2, and TechSIG3.

Table 7 presents descriptive statistics of the groups of companies according to their relationship with institutions. Some observations from the table are as follows. Apparently, the largest companies are the ones that maintain more intense relationships with institutions, both with trade and technical support institutions. On the other hand, companies that hire foreign oenologists need less technical support; however, they do need more trade support. Conversely, wineries with Romanian oenologists behave in the opposite way. Other characteristics do not seem relevant.

Since ANOVA requirements are not met in both cases, we will proceed as above with the analysis by applying non-parametric tests. The results of the Kruskal-Wallis tests for both analyses are shown in

Table 8 and

Table 9.

Based on the results, only for the case of TradeSI can we can find statistically significant differences between the groups of wineries in terms of their international presence. To examine in more detail the differences between groups in this particular case, the Bonferroni-Dunn post-hoc test shows that the international presence of the wineries of the group with higher involvement with TradeSI (TradeSIG3) is higher than and significantly different from the other two groups. Complementarily, the wineries belonging to the first (TradeSIG1) and second (TradeSIG2) groups do not show statistically significant differences between them in terms of their international presence.

5. Conclusions and Proposals

This research has studied the presence, structure, and influence of collaborative networks in contexts of emerging clusters in transition economies. Specifically, empirical evidence of the presence of collaborative networks in these contexts has first been studied. Then, the structure and morphology of these collaborative networks have been deeply analysed. Finally, the influence of these networks developed with both other companies and technical and market support institutions on the intensity of the international presence of cluster firms has been examined.

The results obtained in the Muntenia-Oltenia wine cluster show the presence of a wide network of knowledge relationships between the different wineries that compose the cluster. A more detailed analysis indicates that these relationships not only take place between the nearest wineries geographically, but also between wineries in the different sub-regions of the cluster. This fact confirms the presence of a solid balanced structure of knowledge relationships in the cluster, even when in the initial stages of its life cycle. In this way, market and technical knowledge can flow and be shared throughout the cluster, allowing for balanced growth throughout the territory, especially in these stages where the growth and expansion processes are more intensive.

In addition, the results also confirm the influence of these relationships on the international presence of cluster firms. More specifically, the most integrated companies in the knowledge network of the cluster are developing a greater international presence. The development of a wide range of stable relationships allows their companies to share relevant technical and market knowledge that definitely enables them to improve their international strategies and access new external markets.

On the other hand, the relationships of cluster firms with the cluster institutions are also playing an important role in promoting these internationalisation processes, especially in the case of TradeSI. In this sense, the wineries that are most connected to these institutions are the ones with the greatest international presence. This could be expected since TradeSI are specialised in providing commercial support to cluster firms in areas such as participation in international fairs, training in international trade, development of market studies, trade missions or marketing campaigns abroad, and access to potential foreign customers or finding distributors, among others. Alternatively, the results do not allow us to confirm the influence of the connectedness with TechSI on the international presence of cluster firms. Thus, they may suggest that the wineries with greater links to TechSI seek not only to improve their processes and products to increase the international presence of their products, but also to strengthen their competitive position in local markets. This may be justified by the existence of a growing and more demanding local market.

These results are in line with previous research, especially in highlighting the importance of knowledge flows in fostering advanced strategies in cluster contexts [

3,

4,

5]. However, unlike previous contributions, the context of study allows us to confirm that this influence is also valid in scenarios such as transition economies with clusters in early life cycle stages. This is particularly relevant, since this type of context may lack a priori the maturity, experience, sense of belonging, and internal trust to generate the conditions for knowledge flows to spread properly within the cluster. On the other hand, the results also confirm the influence of the cluster institutions on firm performance, as highlighted by previous research such as McEvily and Zaheer [

47], Molina-Morales and Mas-Verdú [

48], or Boehe [

49]. Nevertheless, in contrast to previous studies, the division of the institutions into two groups makes it possible to further explore this influence.

In summary, this study provides empirical evidence that the factors that explain the behaviour of firms in international markets often lie outside their boundaries, but within the context of regional clusters. Although past research has focused more on explaining export performance from firms’ internal human, technical, commercial, or organisational resources [

50,

51], this work, alternatively, demonstrates that companies’ external resources, particularly their interactions with institutions and other companies in the cluster, are also key elements in explaining their presence in international markets.

Complementing this theoretical contribution, this research also provides important insights for firms, institutions, and policymakers about how to promote cluster firms’ international presence. In this sense, regional government and cluster institutions should encourage internal knowledge flows between cluster firms. The promotion of joint R&D and commercial projects and the development of events, conferences, and knowledge dissemination meetings to put firms in contact with each other to discuss potential business opportunities abroad could be key actions in these processes. On the one hand, besides the improvement of cluster internal knowledge flows, TradeSI should reinforce their actions and strategies in order to extend their influence to the maximum number of cluster firms.

Finally, our article presents different limitations that should be considered. Firstly, only a single industry and cluster has been addressed, with a sample of a limited number of firms. Therefore, the generalization of the results and conclusions should be treated with caution. Further analyses are consequently required in other clusters. Secondly, although our study included different variables, the analysis of the influence of other external variables on firms’ international presence could enrich the final contribution. In this respect, it would be interesting to study the influence of variables such as the presence of foreign direct investments (FDI) or the establishment of knowledge linkages with foreign firms. Thirdly, the study analyses cross-sectional data, so no causal effects can be inferred. This is why the results indicate more a direction in the behaviour of the wineries than a confirmation of a hypothesis. Finally, and complementing the previous idea, it would be worth developing a longitudinal study (instead of cross-sectional) to add more robustness to the present conclusions and to deepen the study of both endogenous and exogenous mechanisms that drive the evolution of the cluster knowledge network. Dealing with these limitations would open the door to future research in this area.