Abstract

Cause sponsorship is one of the most frequently used cause-related marketing (CRM) strategies for extending brand image, often through strategic alliances with nonprofit organizations. Whilst airlines’ corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives have received focused attention in the sustainable tourism literature, the effective development of cause sponsorship has not been understood. In particular, an understanding of airlines’ cause sponsorship of non-sports related charitable causes and their influence on perceived congruence between the airline and its associated causes are limited. In order to address this gap, the study delves into the intersection of entrepreneurial marketing and sponsorship of environmental and/or social causes. It investigates the structural relationship between entrepreneurial marketing, congruence, favorability toward the airline, and purchase intention by analyzing a sample of 443 travelers on US-based full-service airlines using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). The study demonstrates the positive effects of value creation and risk management on congruence, which in turn has a positive influence on travelers’ favorability toward the airline. Further, it confirms that favorability toward the airline predicts purchase intention. This study highlights that entrepreneurial marketing efforts to create customer value, and effective management of the associated risks, are indispensable to successful conveyance of congruent airline sponsorship programs.

1. Introduction

Sustainable tourism literature has been built upon two major strands of sustainability marketing research: a sustainability consumerism (that is, market-led) approach and a product development approach with a focus on environmental and social impacts [1]. The former is associated with identification of market segment needs, where pro-environmental appeals are likely to attract consumers’ “pro-sustainability values, beliefs and behavioral intentions” [1] such as involvement in voluntary carbon offsetting. The latter has focused on producers’ efforts to promote the purchase of sustainable products, which may include message framing for marketing sustainable tourism.

In line with the major research trend in sustainability marketing, the airline industry may be considered as responsible for future generations in terms of its wide range of regional, national, and global environmental and societal impacts. Thus, while getting involved in a process of responsible travel, airlines have been engaged in cause-related marketing (CRM) and/or social marketing through media exposure to maintain and enhance their corporate image. While primarily focusing on sports event sponsorship (i.e., the Olympics and football clubs) in the past [2], airlines have emerged as actively adopting a wide range of CRM strategies. Therefore, in addition to sports events, some of the CRM practices may include sponsorship of charitable causes [3] due to its capability to enhance the corporate image in creative, innovative, and responsible ways. For instance, Air France-KLM has been announced as one of the proactive airlines due to its contribution to local and global communities through the non-sport sponsorship of charitable causes [4] (Air France-KLM, n.d.). Non-profit organizations supported by Air France-KLM include WWF, Red Cross, and Aviation Sans Frontières, to illustrate a few.

Whilst a plethora of commercial organizations has started to enhance the corporate image through alliances with NPOs (Non-profit organizations) [5], it is suggested that consistency, fit, and congruence between the sponsor and the sponsored plays a significant role in enhancing the brand’s reputation and image. However, one of the most complicated brand knowledge areas is understanding the concept of congruence between the brand and its extended meaning through CRM [6]. Importantly, just as implementing corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives requires sophisticated efforts to acquire legitimacy from consumers (e.g., consumers’ attribution, [7,8]), and Pater and Van Lierop [9] suggested a need for more sophisticated communication of CSR messages by corporations (e.g., [10]). de Jong and van der Meer [10] (p. 80) state, “Rather than seeing CSR fit as something that is present or absent, we can see CSR fit as something that takes shape in the communicative actions of organizations…”

Entrepreneurship is thus an indispensable concept to be applied to the volatile tourism industry to improve business performance [11], while creating a congruent brand image with charitable causes. Previous entrepreneurship and business research has identified a clear association between entrepreneurship and business performance (e.g., [12,13,14]). In a similar vein, previous tourism research has investigated how entrepreneurship in tourism and hospitality businesses influence environmental, social, and economic performance (e.g., sales, profitability, satisfaction with performance, sustainability of community, ecotourism, etc.), often in small and medium enterprise (SME) settings [11,15,16,17,18]. Despite prior entrepreneurship and the aforementioned sustainability marketing research, a void exists in the tourism literature in understanding the role of entrepreneurship in forming travelers’ perceptions of an airline’s charitable cause sponsorship. This may partly be due to the fact that a myriad of tourism researchers largely focused on tourists’ attitude toward the destinations and associated behavior intentions (e.g., [19,20,21]).

Specifically, despite considerable academic interest in entrepreneurship, the role of entrepreneurial marketing in entailing positive customer-based brand equity [22] via effective cause sponsorship efforts has been under-researched. Given the recent attention to entrepreneurship, with relevance to business ethics amid divergent constructs of organizational culture (e.g., [12,23]), the concept of entrepreneurial marketing is worthy of investigation to understand the precursors of consumers’ perception of congruence between the sponsor (i.e., the airline brand) and its cause sponsorship. In addition, positive outcomes of congruence have been supported by extant research [24,25,26]. Although a number of studies support the positive effect of congruence on customers’ attitude and behavior, further work is still required in terms of its application to a specific context; specifically, caution is needed before generalizing sponsorship-related congruence outcomes to a specific context. Hence, this study aims to confirm the positive relationships between congruence measured by relevancy and expectancy [27,28], favorability toward the airline, and purchase intention in the context of airline cause sponsorship. In particular, the study focuses on full-service airlines, with a range of differential services for passengers depending on seat classes [29,30,31]. Their price structure is complex, with some influence of price sensitivity on passenger satisfaction, but with a larger influence from service quality, compared with low cost counterparts [32].

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. A Prior Understanding of Airline Cause Sponsorship

Geue and Plewa [8] surveyed 152 undergraduate students regarding (in)congruent oil company-cause associations and highlighted the importance of developing carefully designed cause sponsorship programs (i.e., sponsoring the right cause) while communicating associated CSR initiatives to a range of stakeholders. Prior research has also produced valuable insights into CSR practices in the tourism industry, particularly the airline industry [3,33,34] due to its seeming attribution to climate change. However, an investigation of sponsorship of charitable causes by airlines has not received focused attention, except through the work of Fenclova and Coles [34]. Whilst it has been noted that sponsorship appears in corporate reports as part of CSR policies, Plewa and Quester [35] identified a gap between sponsorship and CSR literature and developed a conceptual framework. They articulated the premise that employees’ and customers’ CSR perceptions are likely influenced by sponsorship exposure, which in turn causes the structural relationship between the CSR perceptions of employees/customers and internal (e.g., employee motivation, satisfaction and retention) and external (i.e., customer satisfaction, purchase and retention) outcomes. Importantly, whilst companies have devoted time and energy to supporting mega-events including sports, a broad range of non-sports related sponsorship opportunities have arisen due to the purported positive sponsorship effects and divergent views on this dimension of CSR, thus bringing about varied perspectives. Recent airline CSR research identified various areas of non-sports related sponsorship, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Prior research identifying types of charity and cause involvement.

Although many tourism researchers have mentioned the importance of CSR activities, an effective promotional tool for CSR-related initiatives, that is, sponsoring charitable causes and/or related charities in tourism businesses, has been under-researched to date. In the past, some airlines (e.g., Aer Lingus, Alitalia, All Nippon Airways, American Airlines, Asiana Airlines, Cathay Pacific, Finnair, JAL, and QUANTAS) promoted causes such as “Change for Good,” whereas others have adopted community volunteering, for example Cathay Pacific [36]. Coles, Fenclova, and Dinan [3] analyzed annual corporate reports by European low-fare airlines, revealing that a number of airlines present sponsorship-related information in terms of community and environment. However, Truong and Hall [36] elicited skepticism concerning the effectiveness of corporate social marketing in support of behavioral change for environmentally friendly actions, whilst public-private partnerships are supposedly subject to termination depending on corporate conditions.

2.2. Entrepreneurial Marketing and Congruence

The concept of entrepreneurship has received a vast amount of attention since Joseph Schumpeter’s emphasis on entrepreneurs’ role as change agents in the context of “chaotic capitalism” in his classical work “Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy” [37]. Likewise, numerous researchers have started to investigate this context, where entrepreneurs acted as “innovators and decision-makers pursuing change” [38]. Innovation was noted in the manufacturing and service industries and was subsequently further recognized in the service industry [39]. In fact, Hjalager [39] illustrated some exemplars of innovative achievements within tourism entrepreneurial businesses: Thomas Cook developed an entertaining travel service concept, Disney Corporation’ innovative ideas culminated in its movies and theme parks, and McDonalds’ innovative approach to food provision exerted its powerful influence far beyond its original sector.

Recently, a number of studies highlighted the intersection of entrepreneurship and marketing [40,41,42]. This is because entrepreneurial marketing plays an important role in competing in the tourism and hospitality industry with its intensely competitive marketplace. Organizations that employ entrepreneurial marketing management are distinct from those practicing traditional marketing, due to its “shorter decision-making process” [43]. Additionally, this entrepreneurial approach is likely to be effective within small and medium enterprises in less economically developed countries, where major marketing channels are non-existent to small indigenous entrepreneurs with limited access to proper institutional support and resources [40]. In this regard, researchers highlighted the need for applying entrepreneurial marketing to travel and tourism [44].

As far as CSR is concerned, [12] emphasized that entrepreneurs tend to play an important role in taking on ethical decision-making processes in the context of “complex, concretely rich value-laden situations.” In particular, they indicated that a sense of creativity and imagination is needed in a changing environment for the purpose of what Buchholz and Rosenthal [12] (p. 309) called a “creative and experimental process,” that is, process ethics. Hence, Buchholz and a colleague highlighted that the spirit of entrepreneurship (i.e., imagination, creativity, novelty, and sensitivity) is instrumental to an ethical approach and/or moral decision-making in organizations and society. Likewise, entrepreneurial marketing has some bearing as precursor to corporate social performance. Furthermore, congruence between the sponsoring companies and cause sponsorship requires careful preparation in order to create the intended effects for participating companies, while communicating corporate sponsorship.

This study is therefore based on the premise that constructing a positive brand image congruent with one of the involved charities is not straightforward, given that congruence arises as a result of consumer evaluations of the so-called fit between the brand and associated sponsorship, defined as relevancy and expectancy [27]. Whereas the former refers to “material pertaining directly to the meaning of (the) theme and reflects how information contained in the stimulus contributes to or detracts from the clear identification of (the) theme or primary message being communicated,” the latter is “the degree to which an item or piece of information falls into some predetermined pattern or structure evoked by (the) theme” [28]. The theme here was referred to as “the general focus of a story to which the plot adheres” as in prior cognitive psychology research [45] (cited in Reference [28] (p. 477)).

The two dimensions of congruence are likely to be influenced by a range of factors including CSR communication, stakeholders, and company characteristics [24]. Thus, a complex process of communication involving companies and customers is required to extend the existing brand’s intended positive meanings and issues via CRM (i.e., reducing poverty, maintaining biodiversity, and helping to solve the global obesity epidemic), whereby the brand image congruent with a specific charitable cause should be created [9]. Therefore, entrepreneurial marketing is argued to play a critical role in developing creative business opportunities (e.g., resource attraction; [46]), as well as in implementing effective sense-making strategies of the process of ensuring brand image congruency with cause sponsorship. The following four sections address how four dimensions of entrepreneurial marketing influence the perceived congruence between the airline brand and sponsorship.

2.2.1. Opportunity Vigilance and Sponsorship Congruence

The first facet of the entrepreneurial marketing concept is opportunity vigilance, which includes proactive orientation and opportunity-driven elements [42,47]. In essence, whereas entrepreneurs tend to focus on identifying opportunities rather than available resources, they tend to redefine market positions with new products and marketing approaches [42]. Whilst CSR and sustainability has been an important issue for companies, Plewa and Quester [35] presented a range of sponsor-related factors (i.e., congruence, prominence, articulation, and leveraging), influencing consumer perception of CSR in a conceptual framework by investigating the link between sponsorship and CSR. In particular, whilst attribution has received continued attention [6,8,48], recent research on consumers’ attribution highlighted the importance of companies’ sincerity in terms of the associated relationship between the business itself and the cause. In other words, people tend to be more attracted to altruistic and/or strategic rather than egoistic- and strategic-driven CSR initiatives [7]. In a similar vein, evidence alludes to the influence of corporate culture, such as market orientation and organizational learning, on the implementation of CSR [49].

Due to the related perceived positive effects, some companies adopt proactive CSR initiatives under a corporate strategy employing “planning and careful consideration by the firm” [42]. In particular, prior research has demonstrated that corporate reputation for proactive initiatives enhances consumer awareness of a company’s goodwill. For instance, Groza, et al. [50] confirmed that proactive initiatives produce positive attribution toward CSR, based on an experimental study of 115 US students. Since consumers’ perception of cause sponsorship was found to be influenced by previous attitude toward both the cause and the brand [51], this research hypothesizes that companies tend to recognize opportunities and implement proactive actions to take advantage of them, leading them to create congruent cause sponsorship in consideration of the airline brand. Hence, it is postulated that:

Hypothesis 1.

Opportunity vigilance is positively associated with the airline-cause sponsorship congruence.

2.2.2. Consumer-Centric Innovativeness and Congruence

Organizations’ attempts to identify market opportunities are predicated on an understanding of customers’ needs, wants, and resources [52,53]. In line with efforts to satisfy customers’ needs, companies have attempted innovative steps such as customer-centric marketing [54]. Specifically, this concept has been described as “innovative ways of seeking and using customer information to create novel sources of value” [47] (p. 79). It has been argued that firms’ need to effectively respond to customers’ needs have led to a range of efforts to communicate, such that a competitive edge is maintained in the marketplace. Drawing upon this perspective of consumer-centric marketing, a number of researchers emphasized the phenomenon that firms tend to pay more attention to an individual consumer than to mass market [52,54]. While some research found that innovative consumer-centric marketing (e.g., parasocial interaction and age identity) has an important role in satisfying consumers through cognitive, psychological and emotional experiences [55,56,57], firms’ innovative and consumer-centric behavior is conducive to consumers’ trust in firms’ business policies, including cause sponsorship. This is because consumer-centric innovativeness assists the firm to identify customers’ demand and implement better-tailored value propositions in cause sponsorship by emphasizing the link between the brand and cause(s) [25]. This approach may often require co-creation marketing, that is, two-way communication [52]. Since companies tend to communicate their CSR initiatives through diverse message channels (i.e., CSR report, Corporate website, PR, advertising, point of purchase, media coverage, word-of-mouth; [58]), the corporate approach to innovation and consumer intensity is more likely to be conducive to a natural and constructed fit through sense-making [10].

Hypothesis 2.

Consumer-centric innovation has a positive influence on the airline-cause sponsorship congruence.

2.2.3. Value Creation and Congruence

Value creation is another important dimension of entrepreneurial marketing, since an organization’s market orientation inevitably fixates on the generation of values and benefits for companies and customers. Companies tend to identify “untapped sources of value for the customer” through marketing efforts and resources in relation to their value creation efforts [47] (p. 71). A number of examples of values to which customers pay attention may be narrowed down to dimensions of “quality/performance, emotional, price, and social” [59], experienced through innovative products or services. In particular, it was found that commercial organizations’ co-creation with NPOs is effective in producing innovative service delivery [60]. Hence, while companies launch various co-creation initiatives with customers [61], the effect of a sense-making process through CRM efforts (i.e., cause sponsorship) on consumers’ perception of a corporation’s CSR is of considerable significance.

Perceived fit versus natural fit (e.g., DenTek Oral Care and diabetes; Ford Motor Company and national parks; [25]) is likely to be achieved through corporate efforts to recognize the potential benefits of supporting certain causes and promoting the relatedness between the company and the cause. In contrast, low fit, translated as negative values, might have negative influences such as decreased clarity, negative thoughts on the sponsorship, and negative influences on attitude toward the sponsorship and the firm’s equity, despite investment in the so-called association [25]. Furthermore, customers are more adept at evaluating, monitoring, and understanding the essence of the corporation’s message, that is, their motive for CSR initiatives: stakeholders’ profit, or an altruistic attitude toward the environment and society. Hence, an appropriate strategy of communicating value creation (e.g., innovation-based strategy of creating social value; [60]) in consideration of stakeholder characteristics (e.g., stakeholder types, issue support, and social value orientation) and company characteristics (e.g., reputation, industry, and marketing strategies) [24] is needed to ensure that a natural or created fit or congruence is presented. Furthermore, previous studies support the preceding argument that the influence of the firm’s previous reputation for creating positive value, particularly social value (i.e., donors’ engagement in and collaboration with social enterprises enabling resource mobilization; [62]), is associated with customers’ positive evaluation of the corporation’s sponsorship of charitable causes [8,63,64].

Hypothesis 3.

Airlines’ value creation activities have a positive influence on the airline-cause sponsorship congruence.

2.2.4. Risk Management and Congruence

Prior research has identified risk-taking as a critical dimension of entrepreneurial orientation, with divergent operationalization of the construct measuring the entrepreneurial individuals’ and firms’ attitude toward the risk [65,66]. More recently, Fiore, Niehm, and Hurst [47] (p. 71) drew upon a study by Morris, Schindehutte, and LaForge [42] to propose risk management and defined it as “a tendency to demonstrate a creative approach to mitigating risks that surround bold, new actions.” In contrast, risk-taking firms are characterized by opportunity-seeking behavior in the face of associated risks.

Whereas a number of potential risks are embedded in the process of alliance between a sponsoring organization and a sponsored entity, literature found that the involved personnel and/or the sponsoring company have an important role in managing, and responding to, associated sponsorship risks in the form of risk-taking versus risk-aversion [67]. Embracing huge demands for CSR, CRM is one of the most influential strategies adopted by contemporary firms to assimilate into their social causes, thus extending their brand image. However, it is argued that congruence or fit requires what Lafferty et al. [68] called “the evolutionary process model,” consisting of communication and adaptation phases. By some coincidence, de Jong and van der Meer [10] emphasized the sense-making process between the consumer and the company, where there seems to be some level of concurrent created and natural fit. Hence, when the sponsoring company has the capability to deal with and/or preempt what Johnston [67] called downside risks (i.e., scandals, endorsers’ negative publicity, etc.), consumers are more likely to perceive congruence between the brand and the cause throughout the company's process of CRM adoption.

Hypothesis 4.

Risk management is positively associated with airline-cause sponsorship congruence.

2.3. Brand-Cause Sponsorship Congruence, Favorability toward the Airlilne, and Purchase Intention

On the one hand, a number of researchers (e.g., [69,70]) have argued that sponsorship is an effective tool for transferring an image or attitude manifested in an object (i.e., non-profit-organization) to a sponsoring firm, sometimes through attitude change. On the other hand, Cornwell, Weeks and Roy [6] highlighted a need to understand the complicated context of sponsorship marketing communications in consideration of the antecedents and outcomes of individuals’ processing mechanics. In this regard, whilst a myriad of previous scholars designed various experimental conditions in the context of sponsorship, it is uncertain which experimental condition is the most important in a certain context. However, there is some agreement on the effects of congruence between brand image and consumers’ attitude. Balance theory also supports individuals’ tendency to change attitude in a positive and/or negative way when faced with inconsistency and imbalance between their prior knowledge regarding, and attitude toward, the sponsor and the charity in the context of sponsorship [6,71]. Based on processing fluency, it is also argued that consumers tend to favorably evaluate congruent brand-cause association [72,73]. In addition, more often than not, consumers may have their own brand image based on what Keller [22] identified as “product attribute, user imagery, brand personality, and functional, experiential and symbolic benefits.” Specifically, Smith [74] demonstrated an effect of consumers’ schema—which is described as a cognitive structure of knowledge in regard to a concept associated with attributes and/or relations [75]—on brand association transfer. Importantly, previous investigations noted that there is an association between congruence and attitudinal (i.e., liking for the sponsorship), affective, and/or behavioral responses. In addition to congruency in a service environment, perceived congruence through social sponsorship has a positive influence on consumers’ emotion and cognitive evaluation of the sponsorship [26,76], bolstering firm equity (i.e., affective and behavior responses; [25]).

Drawing upon the preceding, extant research has supported the relationship between congruence and favorability toward the sponsor, and favorability toward the sponsor and the purchase intention. First, Speed and Thompson [26] built on the classical conditioning framework and found that the favorable sponsorship response is driven by sponsor-event fit, the sponsor’s sincerity, and attitude toward the sponsor. This framework states that attitude toward the unconditioned stimulus, prior attitude toward the conditioned stimulus, and perception of congruence between the unconditioned and conditioned stimulus determines the size of the conditioned response. The authors demonstrated the positive association between fit and favorability toward the event sponsor in response to sponsorship. Likewise, a number of congruent sponsorships supported its influence on a positive attitude toward the sponsor [77,78,79,80].

Second, Demoulin [76] contributed to the understanding of congruence by furthering the mediating effect of the emotional state between congruence and cognitive evaluation of a fast-food restaurant environment, resulting in return intention. Similarly, based on a summary of theoretically grounded research, Cornwell, Weeks, and Roy [6] produced a conceptual framework of consumer-focused sponsorship marketing communications, which postulates the cognitive, affective, and behavioral effects of processing mechanics of sponsorship in consumers’ minds. In line with this framework, Simmons and Becker-Olsen [25] found the effect of a fit between a firm and a sponsored cause, defined as transferability and synergy of intangible associations, on attitude toward the sponsorship (i.e., liking for the sponsorship, favorability of responses to the sponsorship), which in turn produces behavioral intention. In contrast, Speed and Thomson demonstrated the effect of attitude to sponsor on sponsorship response (i.e., willingness to consider the sponsor’s product).

Hypothesis 5.

Brand-cause sponsorship congruence leads to favorability toward the airline.

Hypothesis 6.

Favorability toward the airline leads to purchase intention.

3. Method

3.1. Measures

The proposed model consists of four main concepts (i.e., entrepreneurial marketing, cause sponsorship congruence, favorability, and purchase intention). The metrics for each concept were derived from previous studies, where reliability and validity of measurements and constructs were confirmed. Entrepreneurial marketing comprises four latent constructs, and is measured by 15 items (i.e., five items for opportunity vigilance, four items for consumer-centric innovation, three items for value creation, and three items for risk management), from Fiore, Niehm, Hurst, Son, and Sadachar [47]. Respondents were asked to indicate their opinion with regard to the entrepreneurial marketing of the airline they have used using a five-point Likert scale (from 1 = does not reflect this company to 5 = fully reflects this company). Cause sponsorship congruence was measured by five items from Fleck and Quester [27]. Favorability was measured by three items from Speed and Thompson [26]. Purchase intention was measured by four items from Chiang and Jang [81] and Ahn, Hyun and Kim [82]. Cause sponsorship congruence, favorability and purchase intention were scored using a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree).

All instruments for airline sponsorship were assessed by five airline management experts. Three were working in full-service airline companies’ marketing departments, and two were professors majoring in tourism and hospitality marketing. Based on the experts’ comments, the wording of items was changed and some items were discarded. Then, a sample of 32 graduate students majoring in tourism, who had flown with the airline engaged in cause sponsorship, pre-tested the survey instruments. Cronbach alpha pre-test results confirmed the reliability of each measurement and construct. Following revision of some items based on the graduate students’ feedback, the final main survey questionnaire was completed.

3.2. Data Collection and Sample

For the empirical survey, respondents were recruited from an online survey company, Qualtrics, targeting customers who have traveled by full service airline companies sponsoring causes and were aware that the firms sponsor causes. Appropriate respondents were selected by explaining what airline cause sponsorship is, and through three initial questions: (1) respondents were asked to select every airline on which they have traveled from a list of US-based full-service airline companies sponsoring causes, (2) respondents were asked to write down, among chosen airline companies, which airline brand is the most concerned about sponsoring causes, and (3) we confirmed whether respondents were aware of cause sponsorship/charity involvement by the airline brand. Based on the answers, unqualified participants for the current research were screened out.

The characteristics of 443 respondents are illustrated in Table 2. Respondents included 51.2% females and 48.8% males. Regarding age group, 34.3% were between 20 and 29 years, 30.7% were 30 to 39, 15.4% were 40 to 49, and 17.8% were older than 50 years of age. The majority of respondents were Caucasian (61.8%), and about 67% of the participants had a college or higher degree. The annual household income of 24.8% of the respondents was between US$40,000 and US$60,000, 20.8% was between US$60,000 and US$80,000, 19.6% was between US$20,000 and US$40,000, and that of 15.4% was over US$100,000. The vast majority of participants were employed (71.8%) at the time of the study.

Table 2.

Profile of respondents (n = 443).

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) examined the validity and reliability of the set of items. The results revealed that the measurement model has a substantial model fit to the data, showing χ2 = 550.403, df = 301, χ2/df = 1.829 at p < 0.001, GFI = 0.918, CFI = 0.967, IFI = 0.967, TLI = 0.961, RMSEA = 0.043 [83]. The measurement validity tests comprised convergent and discriminant validity. Convergent validity was assessed based on Fornell and Larcker’s [84] suggestion. As provided in Table 3, scale items’ loadings on each factor are significant at the 0.001 level, and indicate high values ranging from 0.653 to 0.885. Average variance extracted (AVE) for each factor surpassed the cut-off value of 0.5 [85] (see Table 4). Thus, convergent validity was accomplished. Discriminant validity was assessed by using Fornell and Larcker’s [84] suggestion that the AVE value should exceed the squared correlation coefficient between a pair of constructs, or Bagozzi and Yi’s [86] recommendation that there should be a significant difference between a free model and a combined model for a pair of factors. Six pairs of factors unsatisfied by Fornell and Larcker’s [84] suggestion were re-examined using Bagozzi and Yi’s [86] recommendation, and significant differences were confirmed between the free model and the combined model for any pair of factors, showing that discriminant validity was achieved. As shown in Table 4, the composite reliability for each latent construct was greater than the required value of 0.7 (the minimum was 0.817), indicating strong internal consistency.

Table 3.

Confirmatory factor analysis: items and loadings.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics and associated measures.

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

Structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis was used for hypothesis testing. The model fit indices successfully supported a close correspondence between the conceptual model and the data (χ2 = 620.882, df = 310, χ2/df = 2.003 at the p < 0.001, GFI = 0.908, CFI = 0.958, IFI = 0.958, TLI = 0.953, RMSEA = 0.048) [83].

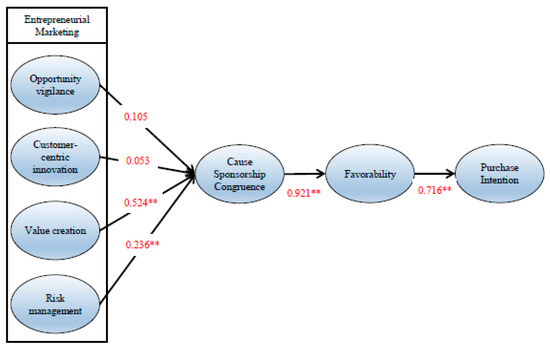

Table 5 and Figure 1 indicate the analysis results of the structural model. Of the four factors of entrepreneurial marketing, opportunity vigilance did not affect cause sponsorship congruence significantly (β = 0.105, p > 0.05), neither did customer-centric innovation (β = 0.053, p > 0.05). Thus, hypotheses 1 and 2 were not supported. However, both value creation (β = 0.524, p < 0.01) and risk management (β = 0.236, p < 0.01) influenced cause sponsorship congruence positively. Hence, hypotheses 3 and 4 were supported. Cause sponsorship congruence was found to have a significant positive effect on favorability (β = 0.921, p < 0.01), supporting hypothesis 5. In addition, favorability was positively related to purchase intention (β = 0.716, p < 0.01), confirming hypothesis 6.

Table 5.

Standardized parameter estimates for the structural model.

Figure 1.

Analysis results of the model. Note: ** p < 0.01.

5. Discussion

In the context of airlines’ sponsorship of social and environmental causes, this study aimed to identify the structural relationship between entrepreneurial marketing, congruence between airline brand as a sponsor and its sponsorship, travelers’ favorability toward the airline, and purchase intention.

First and foremost, the study adopted the bi-dimensional construct of congruence (i.e., relevancy and expectancy) by Fleck and Quester [27]. Maille and Fleck [87] articulated conceptual and measurement issues of congruency while differentiating congruence from some associated concepts such as fit, typicality, and cognitive dissonance, building upon a critique of previous fit and/or congruence studies. This may be in part supported by inconsistent results of previous understanding of congruence/fit in the context of sponsorship. The current investigation is one of the few non-sport sponsorship studies employing the bi-dimensional construct of congruence [8], in line with extant research on incongruent relationships in cognitive psychology literature [28,88]. Thus, it demonstrated a rule of thumb that cause sponsorship programs should carefully consider relevancy and expectancy between the sponsor and environmental and/or social causes. Indeed, the study has proffered an insight that the congruent sponsorship message is valuable to firms to exert synergetic influence on existing brand equity (i.e., purchase intention, favorable behavioral responses, etc.).

Second, this study has predicted the effects of the four-dimensional construct of entrepreneurial marketing on congruence, revealing that as opposed to the other insignificant factors (i.e., opportunity vigilance and consumer centric innovation), value creation and risk management have positive effects on congruence. While the role of value creation between different players has been reported in the business and tourism literature [89,90], this study has further explained risk as a factor to manage throughout sponsorship activities, as addressed by Johnston’s [67] work. A range of responses to alliance risk is highlighted, with value creation as one of the most critical issues for sports sponsorship alliances.

Third, the study has revealed that congruence has a positive influence on travelers’ favorability toward the airline, operationalized by individuals’ emotional and cognitive state. This finding bolsters the previous understanding that when there is a certain level of similarities and relatedness between two entities, emotional and/or cognitive reaction (e.g., identification and perception) is aroused [6,91]. Importantly, the hypothesis between fit and emotional/cognitive attitude (i.e., favorability and interest) has also been supported by Speed and Thompson [26]. Whilst the construct of favorability was measured via items describing affective (i.e., feel more favorable, make me like) and cognitive attitude (i.e., improve my perception), the interest variable was concerned with cognitive reasoning such as “pay attention, notice, and remember” in regard to sponsorship-related knowledge. Wang [92] demonstrated an influence of high fit on affective attitude under high control of navigation, while exploring nonprofit organizations’ websites. In contrast, the effect of high perceived fit on cognitive response (negative/positive thoughts) toward the brand/sponsorship was not found in the same condition. Although prior research has been inconsistent as to the degree to which (in)congruence spawns positive outcomes (e.g., [93]), the current study demonstrated that congruence defined as relevancy and expectancy is positively associated with favorability toward the airline, consistent with prior research employing the same measurement [8].

Finally, the current study found a positive association between favorability toward the airline and purchase intention in response to airlines’ sponsorship, as demonstrated in extant congruence and sponsorship research [25,76]. This finding is also consistent with prior work by de Leaniz, et al. [94], who found a positive influence of green image on the intention to pay in regard to environmentally certified hotels. This study confirmed the importance of affective and behavioral responses in managing and building brand equity [22,25]. Specifically, Keller [22] emphasized brand awareness and brand associations (characterized by favorability and strength, uniqueness, congruence, and leverage) in memory, as far as brand equity is concerned. This study demonstrated that congruent brand associations may be conducive to “[taking] a broad and long-term view of marketing decisions for a brand” [22] (p. 19).

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

Extant tourism research has indicated that tourism organizations are faced with various business constraints that require entrepreneurship within travel organizations for creative environmental, societal, and economic development solutions [16,95,96,97]. Moreover, recent sustainable tourism literature highlighted the potential role of entrepreneurs in developing sustainable tourism practices within a community, albeit in the face of some challenges (i.e., different players’ entrepreneurial instincts jeopardizing environmental and social sustainability; [18]). In the context of sponsorship alliance, Johnston [67] identified the theme “entrepreneurial response” within promotion-focused orientation in event managers’ response to sponsorship risks, while highlighting aspects of “risk-taking and tackling risk as it comes.” However, the limited understanding of the role of entrepreneurial marketing in achieving effective sponsorship programs in the travel industry has been acknowledged. Hence, this research has embarked on filling this gap by investigating the multidimensional construct of entrepreneurial marketing in predicting travelers’ perceived congruence, favorability toward the airline, and behavior intention while responding to the call for further research in entrepreneurial marketing [98]. In particular, the current study has applied the concept of entrepreneurial marketing to full-service airlines in America, whereas a significant amount of extant research on entrepreneurship has focused on entrepreneurial behaviors within small and medium enterprises (SMEs) (e.g., [17,99,100,101]). The theoretical and practical implications of the study results are discussed below.

First, the study has provided valuable additions to the understanding of entrepreneurship in sustainable tourism literature. Despite earlier findings in terms of the potential roles of tourism business entrepreneurs in striving to initiate economic, social, and environmental sustainability [16,18], sustainable tourism research has rarely shed light on entrepreneurial tourism organizations, which adopt effective ways of addressing and communicating CSR initiatives (including sponsorship). Building upon prior research on cause sponsorship [8], the current study highlighted the airline industry as one of many industries that is likely to adopt entrepreneurial marketing amid rapidly changing environments. Prior sponsorship research has primarily focused on highlighting how sponsorship messages will be effectively communicated to audiences, with subsequent effects ensuing (e.g., brand equity). By connecting the dots between two research streamlines (i.e., entrepreneurship and sponsorship) in the context of sustainable tourism, this study emphasized that the strategic points for successful airline sponsorship programs should include value creation for customers (i.e., offering attractive sponsorship programs to create valuable customer experience) and effective management of risks (i.e., creative and innovative approach to minimizing associated risks with reduced cost).

Second, the study expanded on the previous understanding of the positive relationship between corporate association and product evaluations. Prior research suggested that CSR association has a positive influence on the company [102,103], whilst sponsorship literature focuses on the corporation’s sincere motive for positioning with a clear message [6,25,26]. In other words, it has been found that when CSR is perceived as positive, people are more likely to produce emotive (i.e., sensory pleasure) and/or cognitive responses (e.g., customer-corporate identification, interest; product attribute association, etc.) to corporate efforts to extend brand associations [103,104]; sponsor credibility serves to some extent as mediator between CSR perception and responses (e.g., [105]). The current study further supported the link between sponsorship and CSR, to the degree that sponsorship may be intertwined with CSR perception, which in turn leads to internal and external outcomes [35], particularly in the case of airlines, which is congruent with sponsoring environmental and social causes (e.g., [3,33,34,36]) in addition to mega-events such as the Olympics.

6.2. Practical Implications

The study has several practical implications. First, the findings suggest that, given the awareness of value co-creation processes involving mutual engagement in the tourism literature [106], airlines should consider a range of value propositions satisfying multiple stakeholders in order to initiate cause sponsorship. Airline managers should be able to create attractive value from customers’ point of view, based on the strategic and values-driven approach [7], with particular respect to charity involvement. This may proceed with an appropriate knowledge management process, permitting managers to understand customers’ needs and concerns. For instance, a range of charities and/or associated causes with which airlines are concerned, and for which participants in this study have donated their own mileage points, include Red Cross, saving the wildlife, humanitarian programs, cancer, and WWF. With regard to the aforementioned charities and causes, airline managers should be able to align heart (operating objectives) and soul (expression of values) with cause sponsorship [107] in order to avoid the impression of egoistic attribution of sponsorship.

Additionally, airline managers responsible for planning and authorizing corporate philanthropy and/or associated charity involvement should be able to understand numerous risks and adopt relevant tactics (i.e., promotion/prevention/problem-solving focused orientation; [67]) in order to effectively maintain and manage sponsorship relationships. Thus, a clear conceptual understanding of natural and created congruence perceived by travelers is recommended. Drawing upon this understanding, airlines should be able to envisage win-win strategies conducive to enhancing their customer-based brand equity and mobilizing relevant resources for sponsored organizations. While creating congruent company cause-sponsorship programs, airlines need to carefully choose sponsored charities and associated causes to ensure that both the sponsor and the sponsored consider a transparent value creation process along with an appropriate strategy for managing risks.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

This study discovered valuable insights into how travelers may perceive airlines’ sponsorship of environmental and/or social causes, by influencing their attitude and behavior. Several study limitations should be noted when interpreting and applying the findings. First, the sample was limited to customers of US-based full-service airlines, which seem to have the capability to implement ubiquitous sponsorship programs; hence, the current study omitted the understanding of low fare airlines’ sponsorship programs [3,34], albeit their potential exists in some regions. Hence, the study results should be interpreted with caution in consideration of the geographic implications of the business model adopted by the airlines.

Whilst a major issue in literature is to effect behavior change in travelers to address climate change [1,36] and social impacts, this study focused on tourists’ cognitive and affective responses to corporate sponsorship based on their evaluation of the congruency between the airline and its sponsorship initiatives, leading to purchase intention. Hence, this research is based on the premise that there is a market segment in which consumers possess “pro-sustainability values, beliefs, and behavioral intentions” [1] (p. 873). Although the focus was primarily on entrepreneurial marketing as an antecedent to congruence, future avenues of research may include effective message framing in creating congruence between the company and philanthropic activities. Researchers interested in investigating a much bigger picture may also prefer to delve into a range of factors influencing congruence, such as individual/group- (e.g., past experience, knowledge, involvement, arousal, and social alliance), market- (brand equity, clutter, and competitor activities) and management-related factors (e.g., sponsorship policy and activation/leverage). In particular, a longitudinal study of effective sponsorship communication in various contexts such as dimension and types of fit (i.e., [10,108]) may be worth investigating, given the complicated nature of managing congruence. Finally, the gap between attitude and behavior, a frequently mentioned theme, deserves further clarification in the context of sponsorship and CSR in the airline industry.

Author Contributions

J.J.K. and I.K. designed the research model, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper together.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References and Notes

- Font, X.; McCabe, S. Sustainability and marketing in tourism: Its contexts, paradoxes, approaches, challenges and potential. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 869–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atas, U.; Morris, G.; Bat, M. The importance of sponsorhship in corporate communication: A case study of turkish airlines. Glob. Media J. TR Edit. 2015, 6, 35–53. [Google Scholar]

- Coles, T.; Fenclova, E.; Dinan, C. Corporate social responsibility reporting among European low-fares airlines: Challenges for the examination and development of sustainable mobilities. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Air France-KLM. Available online: https://www.flyingblue.com/spend-miles/donate.html?charityfilter=kl (accessed on 1 January 2017).

- Andreasen, A.R. Profits for nonprofits: Find a corporate partner. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1996, 74, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cornwell, T.B.; Weeks, C.S.; Roy, D.P. Sponsorship-linked marketing-opening the black box. J. Advert. 2005, 34, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen, P.S.; Webb, D.J.; Mohr, L.A. Building corporate associations: Consumer attributions for corporate socially responsible programs. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2006, 34, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geue, M.; Plewa, C. Cause sponsorship: A study on congruence, attribution and corporate social responsibility. J. Spons. 2010, 3, 228–241. [Google Scholar]

- Pater, A.; Van Lierop, K. Sense and sensitivity: The roles of organisation and stakeholders in managing corporate social responsibility. Bus. Ethics 2006, 15, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, M.D.T.; Van Der Meer, M. How does it fit? Exploring the congruence between organizations and their corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 143, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajeddini, K. Effect of customer orientation and entrepreneurial orientation on innovativeness: Evidence from the hotel industry in Switzerland. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, R.A.; Rosenthal, S.B. The spirit of entrepreneurship and the qualities of moral decision making: Toward a unifying framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 60, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, A.; Wiklund, J.; Lumpkin, G.T.; Frese, M. Entrepreneurial orientation and business performance: An assessment of past research and suggestions for the future. Entrep. Theory Prac. 2009, 33, 761–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, J.; Shepherd, D. Entrepreneurial orientation and small business performance: A configurational approach. J. Bus. Ventur. 2005, 20, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.H.; Iankova, K.; Zhang, Y.; McDonald, T.; McDonald, T.; Qi, X. The role of self-gentrification in sustainable tourism: Indigenous entrepreneurship at Honghe Hani Rice Terraces World Heritage Site, China. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 1262–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallak, R.; Assaker, G.; Lee, C. Tourism entrepreneurship performance: The effects of place identity, self-efficacy, and gender. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallak, R.; Brown, G.; Lindsay, N.J. The Place Identity—Performance relationship among tourism entrepreneurs: A structural equation modelling analysis. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, B.S.; Gillen, J.; Friess, D.A. Challenging the principles of ecotourism: Insights from entrepreneurs on environmental and economic sustainability in Langkawi, Malaysia. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S. Appraisal determinants of tourist emotional responses. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, L.; Moscardo, G.; Benckendorff, P. Using Brand Personality to Differentiate Regional Tourism Destinations. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, I. Change and stability in shopping tourist destination networks: The case of Seoul in Korea. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. J. Market. 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.D.; Sapienza, H.J.; Bowie, N.E. Ethics and entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2009, 24, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Maximizing business returns to corporate social responsibility (CSR): The role of CSR communication. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, C.J.; Becker-Olsen, K.L. Achieving marketing objectives through social sponsorships. J. Mar. 2006, 70, 154–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speed, R.; Thompson, P. Determinants of sports sponsorship response. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleck, N.D.; Quester, P. Birds of a feather flock together… definition, role and measure of congruence: An application to sponsorship. Psychol. Mark. 2007, 24, 975–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckler, S.E.; Childers, T.L. The role of expectancy and relevancy in memory for verbal and visual information: What is incongruency? J. Consum. Res. 1992, 18, 475–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, Y.-C.; Chen, Y.-H. Factors influencing the intentions of passengers regarding full service and low cost carriers: A note. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2010, 16, 226–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koklic, M.K.; Kukar-Kinney, M.; Vegelj, S. An investigation of customer satisfaction with low-cost and full-service airline companies. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 80, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.M.C.; Fialho, A.F. The role of intrinsic in-flight cues in relationship quality and behavioural intentions: Segmentation in less mindful and mindful passengers. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 948–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaguru, R. Role of value for money and service quality on behavioural intention: A study of full service and low cost airlines. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2016, 53, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowper-Smith, A.; De Grosbois, D. The adoption of corporate social responsibility practices in the airline industry. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenclova, E.; Coles, T. Charitable Partnerships among Travel and Tourism Businesses: Perspectives from Low-Fares Airlines. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 13, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plewa, C.; Quester, P.G. Sponsorship and CSR: Is there a link? A conceptual framework. Int. J. Sport Mark. Spons. 2011, 12, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, V.D.; Hall, C.M. Corporate social marketing in tourism: To sleep or not to sleep with the enemy? J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 884–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelson, R.J. Schumpeter: The prophet. Newsweek, 11 September 1992; 61. [Google Scholar]

- Pinfold, J. Tourism and Small Entrepreneurs: Development, National Policy and Entrepreneurial Culture: Indonesian Cases; Cognizant Communication Corporation: New York, NY, USA, 1999; p. 165. ISBN 1-882345-25-8. [Google Scholar]

- Hjalager, A.-M. A review of innovation research in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlisle, S.; Kunc, M.; Jones, E.; Tiffin, S. Supporting innovation for tourism development through multi-stakeholder approaches: Experiences from Africa. Tour. Manag. 2013, 35, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurgun, H.; Bagiran, D.; Ozeren, E.; Maral, B. Entrepreneurial marketing—The interface between marketing and entrepreneurship: A qualitative research on boutique hotels. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. 2011, 26, 340–357. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, M.H.; Schindehutte, M.; LaForge, R.W. Entrepreneurial Marketing: A Construct for Integrating Emerging Entrepreneurship and Marketing Perspectives. J. Mark. Theory Prac. 2002, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collinson, E.; Shaw, E. Entrepreneurial marketing—A historical perspective on development and practice. Manag. Decis. 2001, 39, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, A.; Rimmington, M.; Williams, C. Entrepreneurship in the Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure Industries; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Thorndyke, P.W. Cognitive structures in comprehension and memory of narrative discourse. Cogn. Psychol. 1977, 9, 77–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamel, G. Bringing Silicon Valley Inside. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1999, 77, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fiore, A.M.; Niehm, L.S.; Hurst, J.L.; Son, J.; Sadachar, A. Entrepreneurial marketing: Scale validation with small, independently-owned businesses. J. Mark. Dev. Compet. 2013, 7, 63–86. [Google Scholar]

- Andreu, L.; Casado-Díaz, A.B.; Mattila, A.S. Effects of message appeal and service type in CSR communication strategies. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1488–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Hansen, E.; Panwar, R.; Hamner, R.; Orozco, N. Connecting market orientation, learning orientation and corporate social responsibility implementation: Is innovativeness a mediator? Scand. J. For. Res. 2013, 28, 784–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groza, M.D.; Pronschinske, M.R.; Walker, M. Perceived organizational motives and consumer responses to proactive and reactive CSR. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 102, 639–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, B.A.; Goldsmith, R.E.; Hult, G.T.M. The impact of the alliance on the partners: A look at cause–brand alliances. Psychol. Mark. 2004, 21, 509–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Sisodia, R.S.; Sharma, A. The Antecedents and Cosequences of Customer-centric marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, M.; Kim, I. In-flight NCCI management by combining the Kano model with the service blueprint: A comparison of frequent and infrequent flyers. Tour. Manag. 2018, 69, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niininen, O.; Buhalis, D.; March, R. Customer empowerment in tourism through consumer centric marketing (CCM). Qual. Mark. Res. 2007, 10, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, W.; Schmitt, B.; Meyer, A. How does perceived firm innovativeness affect the consumer? J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Kim, J.J. Older adults’ parasocial interaction formation process in the context of travel websites: The moderating role of parent-child geographic proximity. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 399–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Ahn, Y.-J.; Kim, I. The effect of older adults’ age identity on attitude toward online travel websites and e-loyalty. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 2921–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C.; Sen, S. What Board Members Should Know about Communicating CSR. In Proceedings of the Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance and Financial Regulation, Cambridge, MA, USA, 26 April 2011; Available online: https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2011/04/26/what-board-members-should-know-about-communicating-corporate-social-responsibility/ (accessed on 4 July 2018).

- Sweeney, J.C.; Soutar, G.N. Consumer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerawardena, J.; Mort, G.S. Competitive strategy in socially entrepreneurial nonprofit organizations: Innovation and differentiation. J. Public Policy Market. 2012, 31, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. Customer involvement in sustainable supply chain management. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2014, 55, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altinay, L.; Sigala, M.; Waligo, V. Social value creation through tourism enterprise. Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.; Cameron, G.T. Conditioning effect of prior reputation on perception of corporate giving. Public Relatst. Rev. 2006, 32, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szykman, L.R.; Bloom, P.N.; Blazing, J. Does corporate sponsorship of a socially-oriented message make a difference? An investigation of the effects of sponsorship identity on responses to an anti-drinking and driving message. J. Consum. Psychol. 2004, 14, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Baird, I.S.; Thomas, H. Toward a contingency model of strategic risk taking. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Dess, G.G. Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1996, 21, 135–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, M.A. The sum of all fears: Stakeholder responses to sponsorship alliance risk. Tour. Manag. Perspec. 2015, 15, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, B.A.; Lueth, A.K.; McCafferty, R. An Evolutionary Process Model of Cause-Related Marketing and Systematic Review of the Empirical Literature. Psychol. Mark. 2016, 33, 951–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwell, T.B.; Smith, R.K. The communications importance of consumer meaning in cause-linked events: Findings from a US event for benefiting breast cancer research. J. Mark. Commun. 2001, 7, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwinner, K. A model of image creation and image transfer in event sponsorship. Int. Mark. Rev. 1997, 14, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, D.H. Associating the corporation with a charitable event through sponsorship: Measuring the effects on corporate community relations. J. Advert. 2002, 31, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.Y.; Labroo, A.A. The effect of conceptual and perceptual fluency on brand evaluation. J. Mark. Res. 2004, 41, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cogn. Psychol. 1973, 5, 207–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G. Brand image transfer through sponsorship: A consumer learning perspective. J. Mark. Manag. 2004, 20, 457–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, S.T.; Taylor, S.E. Social Cognition; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Demoulin, N.T. Music congruency in a service setting: The mediating role of emotional and cognitive responses. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2011, 18, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcañiz, E.B.; Cáceres, R.C.; Pérez, R.C. Alliances Between Brands and Social Causes: The Influence of Company Credibility on Social Responsibility Image. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 96, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Olsen, K.L.; Cudmore, B.A.; Hill, R.P. The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigné, E.; Currás-Pérez, R.; Aldás-Manzano, J. Dual nature of cause-brand fit. Eur. J. Mark. 2012, 46, 575–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, E.L. Does sponsorship work in the same way in different sponsorship contexts? Eur. J. Mark. 2010, 44, 180–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.-F.; Jang, S.S. The effects of perceived price and brand image on value and purchase intention: Leisure travelers’ attitudes toward online hotel booking. J. Hosp. Leisure Mark. 2007, 15, 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Y.-J.; Hyun, S.S.; Kim, I. Vivid-memory formation through experiential value in the context of the international industrial exhibition. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 291–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maille, V.; Fleck, N. Perceived congruence and incongruence: Toward a clarification of the concept, its formation and measure. Rech. Appl. Mark. 2011, 26, 77–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, G.S. Picture memory: How the action schema affects retention. Cogn. Psychol. 1980, 12, 473–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novelli, M.; Morgan, N.; Mitchell, G.; Ivanov, K. Travel philanthropy and sustainable development: The case of the Plymouth–Banjul Challenge. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 824–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonsky, M.; Hall, J.; Vieceli, J.; Atay, L.; Akdemir, A. Using strategic philanthropy to improve heritage tourist sites on the Gallipoli Peninsula, Turkey: Community perceptions of changing quality of life and of the sponsoring organization. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 376–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.U.M.; Park, S.-Y.; Rapert, M.I.; Newman, C.L. Does perceived consumer fit matter in corporate social responsibility issues? J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1558–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Affective and cognitive influence of control of navigation on cause sponsorship and non-profit organizations. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sec. Mark. 2015, 20, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers-Levy, J.; Tybout, A.M. Schema congruity as a basis for product evaluation. J. Consum. Res. 1989, 16, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leaniz, P.M.G.; Crespo, Á.H.; López, R.G. Customer responses to environmentally certified hotels: The moderating effect of environmental consciousness on the formation of behavioral intentions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roxas, B.; Chadee, D. Effects of formal institutions on the performance of the tourism sector in the Philippines: The mediating role of entrepreneurial orientation. Tour. Manag. 2013, 37, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.; Rees, P.; Murray, N. Turning entrepreneurs into intrapreneurs: Thomas Cook, a case-study. Tour. Manag. 2016, 56, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, K.K.; DeVereaux, C. A theoretical framework for sustaining culture: Culturally sustainable entrepreneurship. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 62, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, G.E.; Hultman, C.M.; Miles, M.P. The evolution and development of entrepreneurial marketing. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2008, 46, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klewitz, J.; Hansen, E.G. Sustainability-oriented innovation of SMEs: A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCamley, C.; Gilmore, A. Aggravated fragmentation: A case study of SME behaviour in two emerging heritage tourism regions. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanhill, S. Small and medium tourism enterprises. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 132–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigné-Alcañiz, E.; Currás-Pérez, R.; Ruiz-Mafé, C.; Sanz-Blas, S. Cause-related marketing influence on consumer responses: The moderating effect of cause–brand fit. J. Mark. Commun. 2012, 18, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.J.; Dacin, P.A. The company and the product: Corporate associations and consumer product responses. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, D.R.; Drumwright, M.E.; Braig, B.M. The effect of corporate social responsibility on customer donations to corporate-supported nonprofits. J. Market. 2004, 68, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifon, N.J.; Choi, S.M.; Trimble, C.; Li, H. Congruence effects in sponsorship: The mediating role of sponsor credibility and consumer attributions of sponsor motive. J. Adver. 2004, 33, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, A.R.-D. Considering the role of agritourism co-creation from a service-dominant logic perspective. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 354–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, R. Give and Take; Harvard Business School Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, E.L.; Thjømøe, H.M. Explaining and articulating the fit construct in sponsorship. J. Adver. 2011, 40, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).