Organic Private Labels as Sources of Competitive Advantage—The Case of International Retailers Operating on the Polish Market

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Private Label

1.2. Organic Food Sector in Poland

1.3. Competitive Advantage

2. Methods and Methodology

2.1. Aim of the Study

- -

- an analysis of factors determining a given retailer’s decision to introduce OPLs;

- -

- an analysis of the contributors of the CA, including type of PLs, assortment, specific attributes of organic food, sustainability, prices, and retailer-based advantages;

- -

- identification and analysis of the drivers of the CA in relation to each contributor;

- -

- assortment and price analysis of OPLs offered by retail operators on the Polish market;

- -

- analysis of the OPLs’ branding elements.

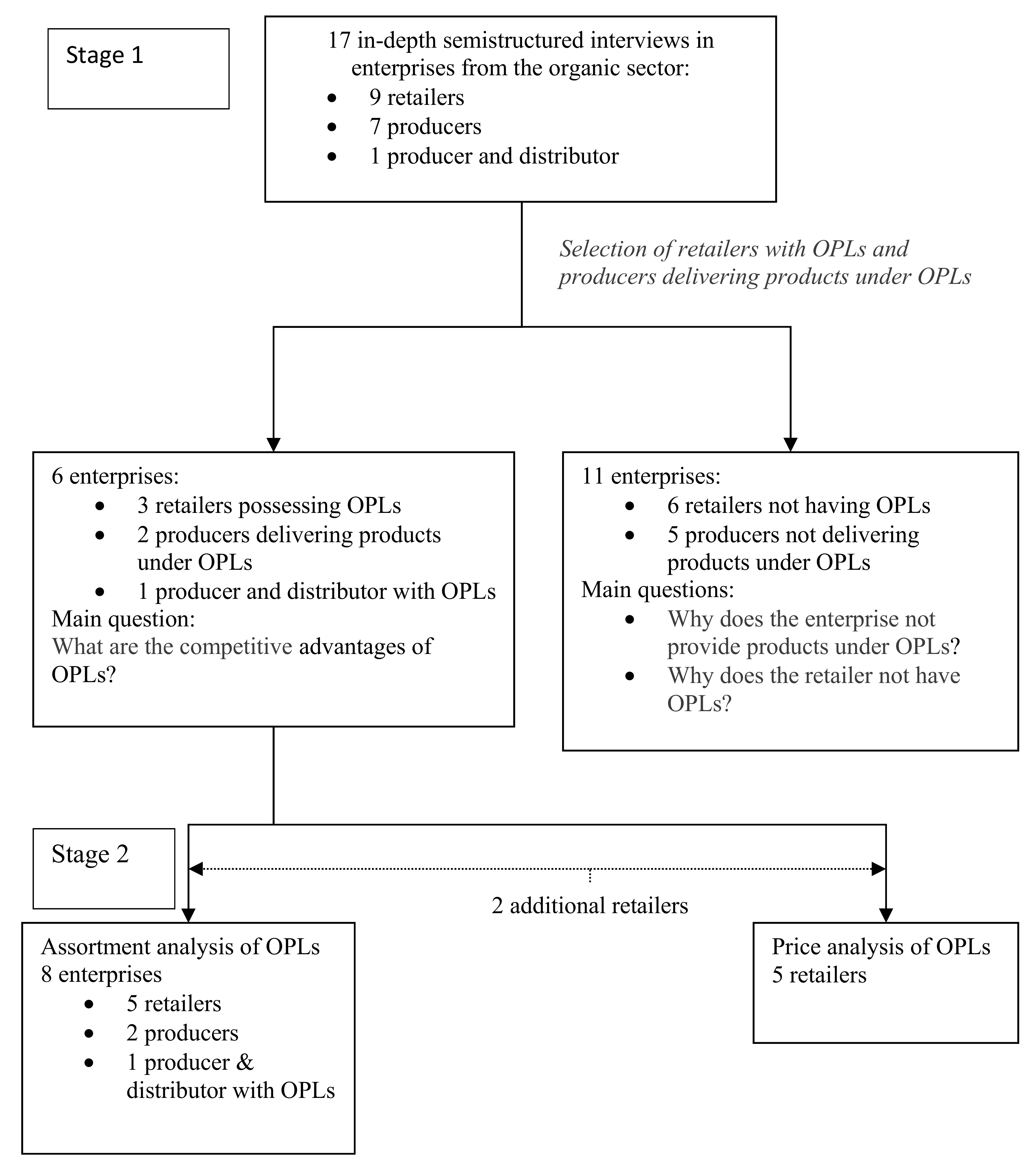

2.2. Research Methods

2.3. Data Collection Process

2.4. Participants

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Organic PLs—General Approach

R2 “If the supplier is a big player, then expanding the PLs will not negatively affect its portfolio. If it is a local supplier, it cannot produce PLs because there is no such capacity. Introducing a PL with someone else may be a threat to that company. The emergence of the PL may also be a chance to cooperate.”

- foreign OPLs and a foreign supplier,

- foreign OPLs and a domestic supplier,

- OPLs created for the Polish market and a Polish supplier,

- OPLs created for the Polish market and a foreign supplier.

R1: “When we started, in the first years there were mainly imported products, and from the very beginning of opening we had PL products on the market, only our PL is both local and international.”

- deliveries of organic food,

- deliveries for the PLs.

R1: “It is difficult to say whether the requirements are different for products, whether domestic or foreign. If we import a product from a local supplier, at the outset we determine what the quality level must be, what requirements the product must meet. Those that are imported do not assume our requirements here, this happens at the level of the country that the product comes from. Each country introducing a product takes into account the market to which the product is introduced. The products that we have on sale are made either only for our parent market or for other countries.”

3.2. Competitive Advantage of OPLs

3.3. PLs-Based Competitive Advantage

3.4. Assortment-Based Competitive Advantage

R3: “There is more room to maneuver (…), a comprehensive approach, trend forecasting, and client searches for such products, so we must have them in our offer…”

R1: “The variety of products is our strategy, we want to meet the expectations of those consumers who are looking for gluten-free, healthy, ecological, local, national and other products.”

3.5. Organic-Attributes-Based Competitive Advantage

R3: “…for the retailer, OPLs mean ‘promoting health’”

P1: “ in Poland, the egoistic approach—the health benefit—dominates”

P2: “…a safe product, devoid of herbicides or pesticides, it is not genetically modified. (…) it is in one dimension, such as health … “

R1: “For us, the risk is one-failure to maintain the quality of the product. [If] we sell as organic, and then after the results of research it turns out that the non-ecological product must be withdrawn, a media crisis is emerging. The issue of disloyalty and falsification of the product—here is the risk. This is mainly about our brand, where we sign our logo.”

3.6. Sustainability-Based Competitive Advantage

P1: “It is pesticide-free food.”

P1: “…. crops are less harmful to the environment than conventional ones.”

P2: “[In] other dimensions, such as environmental protection, sustainable development and animal welfare (…) organic food is not only healthy, but also the philosophy of life, which means caring about environmental protection, sustainable development and animal welfare, which is very important.”

R1: “… ecological products also bring with them issues of tradition and the environmental protection that is connected with it, they have a lot of advantages related to limiting the level, processing and complexity of the product.”

P3: “Each retail network will build PLs, social responsibility is important.”

R1: “… our goal is to maintain cooperation with suppliers as long as possible.”

3.7. Price-Related Competitive Advantage

R1: “(…) our weakness, (…) the barrier is price. Perhaps now this barrier is smaller, but until recently the prices proposed by the suppliers were very high, [and] we have a rule that our own brand must be available to the customer in a given price range.”

- the difference between organic products sold under PLs and the producer brand,

- the difference between organic products sold under discount OPLs vs non-discount OPLs,

- the difference between products sold as OPLs and PLs.

R1: “Organic food under private labels will be cheaper (…) It seems to me that if someone is looking for an organic product, that person does not look whether it is a private label or a national brand.”

R2: “The price can be a strong point, showing that organic products are not only exclusive products, intended only for a selected social group that can afford such food. We increase the availability of this product group.”

R1: “The price difference between organic and conventional food depends on the product, but these are the upper limits; a few years ago it was 45%, and not 20.”

3.8. Retailer-Based Competitive Advantage

P2: “Here, value can be added to the overall values attributed to eco-friendly products if the retailer is convinced that these products under its PLs are subject to special supervision and have been specially selected. This is a double value. This is a sign of the quality of this retailer, we take responsibility for it, we have checked it. We guarantee that although this product is certified and safe, we have checked and verified it. If the retailer convinces its consumers [about] organic products under the PL of that retailer, they will be competitive with organic products under the producer brand, because this is a lower price and a double certificate.”

P1: “Owning the PL builds one’s market position, one is not anonymous on the market”

P1: “the consumers of organic food are more interested in the origin of the product, its path from the field to the table; owning a PL helps to give credence to the fact that they are familiar with the production of such food.”

R1: “it is rather constant cooperation. We have many examples of suppliers that we have been with since the very first day, for nearly 20 years.”

R1: “…just as every brand builds its trust, the case is the same for the domestic supplier. Every supplier builds his/her trust, a known one will be perceived better, and a less known one worse, or vice versa—it’s better because it’s from my region and I know the supplier.”

4. Conclusions

- The competitive advantage of OPLs that results from the type of PLs is due to brand architecture and adoption of either a house of brands or a branded house strategy. New PLs have been introduced for organic food with elements supporting individualization and identification of the organic category.

- The assortment-based competitive advantage can be described by the number and types of categories, specific products, and innovations. Retailers exclusively offer certain organic products that are not available in competing chains. This gives them the opportunity to underline the uniqueness of the product offer and to attract consumers who are looking for products with a specific added value at affordable prices.

- The organic-attributes-based competitive advantage is associated with health and naturalness, organic quality, and a certified process of production. The introduction of OPLs allows international retailers to position themselves as chains promoting a healthy lifestyle.

- The sustainability-based competitive advantage is determined by organic food perceived as a product category that respects sustainable development and the natural environment, and enhances a shift towards more ethical and responsible food consumption also in terms of other credence attributes such as animal welfare.

- Another important area of the CA of retailers as derived from OPLs is the management of relations with suppliers. Long-term cooperation based on trust helps to achieve mutual benefits and to reduce the risk of inadequate quality. At the same time, the perception of PLs related to the image of the retailer constitutes an additional element that guarantees, in the minds of the consumers, the quality of an end product and becomes an important contributor of the CA for retailers.

- Price positioning places the PLs of organic food below the producer’s brands and above the PLs for non-organic products. A favorable price combined with the attributes of organic food determines the growing interest of consumers in PLs. At the same time, it separates sub-brands by highlighting the various attributes of organic food that are created for the PLs of organic food. This supports the use of positioning strategies that place the OPLs in the higher quality and price segments.

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vale, R.; Verga Matos, P.; Caiado, J. The impact of private labels on consumer store loyalty: An integrative perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 28, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semeijn, J.; van Riel, A.C.R.; Ambrosini, A.B. Consumer evaluations of store brands: Effects of store image and product attributes. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2004, 11, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abril, C.; Rodriguez-Cánovas, B. Marketing mix effects on private labels brand equity. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2016, 25, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoskins, J.D. Offering value and capturing surplus: A strategy for private label sales in a new customer loyalty building scenario. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 28, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dursun, İ.; Kabadayı, E.T.; Alan, A.K.; Sezen, B. Store Brand Purchase Intention: Effects of Risk, Quality, Familiarity and Store Brand Shelf Space. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 24, 1190–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakkos, N.; Trivellas, P.; Sdrolias, L. Identifying Drivers of Purchase Intention for Private Label Brands. Preliminary Evidence from Greek Consumers. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 175, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gázquez-Abad, J.C.; Martínez-López, F.J.; Esteban-Millat, I. The role of consumers’ attitude towards economic climate in their reaction to “PL-only” assortments: Evidence from the United States and Spain. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 34, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vroegrijk, M.; Gijsbrechts, E.; Campo, K. Battling for the Household’s Category Buck: Can Economy Private Labels Defend Supermarkets against the Hard-Discounter Threat? J. Retail. 2016, 92, 300–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carsana, L.; Jolibert, A. Influence of iconic, indexical cues, and brand schematicity on perceived authenticity dimensions of private-label brands. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 40, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebri, M.; Zaccour, G. Cross-country differences in private-label success: An exploratory approach. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 80, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Bao, Y.; Sheng, S. Motivating purchase of private brands: Effects of store image, product signatureness, and quality variation. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan Choi, S. Defensive strategy against a private label: Building brand premium for retailer cooperation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 34, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Steenkamp, J.-B.E.M. Private Label Strategy: How to Meet the Store Brand Challenge; Harvard Business School Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 2007; ISBN 9781422101674. [Google Scholar]

- De Wulf, K.; Odekerken-Schröder, G.; Goedertier, F.; Van Ossel, G. Consumer perceptions of store brands versus national brands. J. Consum. Mark. 2005, 22, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodur, H.O.; Tofighi, M.; Grohmann, B. When Should Private Label Brands Endorse Ethical Attributes? J. Retail. 2016, 92, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DelVecchio, D. Consumer perceptions of private label quality: The role of product category characteristics and consumer use of heuristics. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2001, 8, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, R.; Matsubayashi, N. Premium store brand: Product development collaboration between retailers and national brand manufacturers. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 185, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethuraman, R.; Gielens, K. Determinants of Store Brand Share. J. Retail. 2014, 90, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ailawadi, K.L.; Pauwels, K.; Steenkamp, J.-B.E. Private-Label Use and Store Loyalty. J. Mark. 2008, 72, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawes, J.; Nenycz-Thiel, M. Analyzing the intensity of private label competition across retailers. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyskens, I.; Gielens, K.; Gijsbrechts, E. Proliferating Private-Label Portfolios: How Introducing Economy and Premium Private Labels Influences Brand Choice. J. Mark. Res. 2010, 47, 791–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngobo, P.-V. Private label share, branding strategy and store loyalty. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2011, 18, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnittka, O. Are they always promising? An empirical analysis of moderators influencing consumer preferences for economy and premium private labels. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2015, 24, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retnawati, B.B.; Ardyan, E.; Farida, N. The important role of consumer conviction value in improving intention to buy private label product in Indonesia. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Rise and Rise again of Private Label. Available online: http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/reports/2018/the-rise-and-rise-again-of-private-label.html (accessed on 9 June 2018).

- Nielsen: Marki Własne Przechodzą Rewolucję. to Coraz Większe Wyzwanie dla Producentów—Handel/dystrybucja—Raporty. Available online: http://www.portalspozywczy.pl/raporty/nielsen-marki-wlasne-przechodza-rewolucje-to-coraz-wieksze-wyzwanie-dla-producentow,157540.html (accessed on 9 June 2018).

- Private Brands Leverage Today’s Trends|Packaging World. Available online: https://www.packworld.com/article/private-brands-leverage-todays-trends (accessed on 9 June 2018).

- Market Share of Private Label Fast-Moving Consumers Goods (FMCG) Sales Worldwide in 2015, by Country. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/753082/global-private-label-market-share/ (accessed on 9 June 2018).

- Olbrich, R.; Jansen, H.C.; Hundt, M. Effects of pricing strategies and product quality on private label and national brand performance. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 34, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Private Label Market (PLMA). Private Label’S Market Share Reaches All-Time Highs in 9 European Countries. Priv. Label Today 2017, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śmigielska, G. Kreowanie Przewagi Konkurencyjnej w Handlu Detalicznym; Wydawnictwo Akademii Ekonomicznej w Krakowie: Kraków, Poland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Liderzy i Trendy w Handlu. Available online: http://www.mspos.pl/liderzy-i-trendy-w-handlu-2016/ (accessed on 4 July 2018).

- Deloitte. Deloitte Global Powers of Retailing 2017: The Art and Science of Customers; Deloitte: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Grupa Eurocash. Annual Reports 2017. Available online: http://eurocash.pl/pub/pl/uploaddocs/raporty-okresowe/eurocash-raport-roczny-2017.1521823354.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2018).

- Grupa Eurocash. Annual Reports 2015. Available online: http://eurocash.pl/pub/pl/uploaddocs/raporty-okresowe/eurocash-sa-jednostkowy-raport-roczny-2015.1458319854.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2018).

- Górska-Warsewicz, H. Zachowania konsumentów wobec marek w sytuacjach kryzysowych. Probl. Zarz. 2013, 11, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górska-Warsewicz, H.; Czeczotko, M. Analysis of Product Strategies of Dairy Trade Brands in Biedronka and Lidl Discounters. Probl. Zarz. 2016, 57, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czeczotko, M.; Kulykovets, O.; Kudlińska-Chylak, A.; Górska-Warsewicz, H. Postrzeganie marek własnych sieci hurtowej Makro Cash & Carry przez odbiorców profesjonalnych z sektora usług gastronomicznych. Handel Wewnętrzny 2017, 3, 265–274. [Google Scholar]

- Pepe, M.S.; Abratt, R.; Dion, P. The impact of private label brands on customer loyalty and product category profitability. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2011, 20, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Christodoulopoulou, A. Sustainability and branding: An integrated perspective. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2014, 43, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisimova, T.; Sultan, P. The Role of Brand Communications in Consumer Purchases of Organic Foods: A Research Framework. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2014, 20, 511–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, S.; Vranken, L. Green market expansion by reducing information asymmetries: Evidence for labeled organic food products. Food Policy 2013, 40, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, A.; Vecchio, R. Organic Farming and Sustainability in Food Choices: An Analysis of Consumer Preference in Southern Italy. Agric. Agric. Sci. Procedia 2016, 8, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbo, C.; Lamastra, L.; Capri, E. From environmental to sustainability programs: A review of sustainability initiatives in the Italian wine sector. Sustainability 2014, 6, 2133–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia, A.; de Magistris, T. The demand for organic foods in the South of Italy: A discrete choice model. Food Policy 2008, 33, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chkanikova, O.; Lehner, M. Private eco-brands and green market development: Towards new forms of sustainability governance in the food retailing. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 107, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banterle, A.; Cereda, E.; Fritz, M. Labelling and sustainability in food supply networks. Br. Food J. 2013, 115, 769–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nenycz-Thiel, M.; Romaniuk, J. Understanding premium private labels: A consumer categorisation approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ter Braak, A.; Geyskens, I.; Dekimpe, M.G. Taking private labels upmarket: Empirical generalizations on category drivers of premium private label introductions. J. Retail. 2014, 90, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimhan, C.; Wilcox, R.T. Private Labels and the Channel Relationship: A Cross-Category Analysis. J. Bus. 1998, 71, 573–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins-Dodd, C.; Lindley, T. Store brands and retail differentiation: The influence of store image and store brand attitude on store own brand perceptions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2003, 10, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, D.; Krishnan, R.; Baker, J.; Borin, N.; Krishnan Is, R. The Effect of Store Name, Brand Name and Price Discounts on Consumers’ Evaluations and Purchase Intentions. J. Retail. 1998, 74, 331–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miquel-Romero, M.J.; Caplliure-Giner, E.M.; Adame-Sánchez, C. Relationship marketing management: Its importance in private label extension. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willer, H.; Lernoud, J. The World of Organic Agriculture 2017: Summary; Institute of Organic Agriculture and IFOAM—Organic International: Frick, Germany, 2017; ISBN 9783037360408. [Google Scholar]

- Inspekcja Jakości Handlowej Artykułów Rolno-Spożywczych. Raport o Stanie Rolnictwa Ekologicznego w Polsce w Latach 2015–2016; Inspekcja Jakości Handlowej Artykułów Rolno-Spożywczych: Warsaw, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wier, M.; Calverley, C. Market potential for organic foods in Europe. Br. Food J. 2002, 104, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żakowska-Biemans, S. Polish consumer food choices and beliefs about organic food. Br. Food J. 2011, 113, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euromonitor International. Organic Packaged Food in Poland; Passport; Euromonitor International: London, UK, 2017; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Zakowska-Biemans, S. (Ed.) Marketing, Promocja Oraz Analiza Rynku, Analiza Rynku Produkcji Ekologicznej w Polsce, w tym Określenie Szans i Barier Dla Rozwoju Tego Sektora Produkcji. Available online: http://wnzck.sggw.pl/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Dotacja_na_badania_rolnictwo_ekologiczne.pdf (accessed on 4 July 2018).

- Śmigielska, G. Kształtowanie przewagi konkurencyjnej w handlu detalicznym w świetle teorii M. Portera. Zeszyty Naukowe Akademia Ekonomiczna w Krakowie 2004, 664, 57–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bozhinova, M. Private Label—Retailers’ Competitive Strategy. Glob. J. Manag. Bus. Res. 2014, 13, 29–33. Available online: https://globaljournals.org/GJMBR_Volume13/5-Private-Label-Retailers-Competitive-Strategy.pdf (accessed on 4 July 2018).

- Pepe, M.S.; Abratt, R.; Dion, P. Competitive advantage, private-label brands, and category profitability. J. Mark. Manag. 2012, 28, 154–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakan Altıntaş, M.; Kılıç, S.; Senol, G.; Bahar Isin, F. Strategic objectives and competitive advantages of private label products. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2010, 38, 773–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra Consuegra, O.; Kitchen, P. Own labels in the United Kingdom: A source of competitive advantage in retail business. Pensamiento Gestión 2006, 21, 114–161. [Google Scholar]

- Whelan, P. Trends in Retail Competition: Private Labels, Brands and Competition Policy; British Institute of International and Comparative Law: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sansone, M. The strategic role of private label. In Handbook of Research on Retailer-Consumer Relationship Devel-Opment; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance; Free Press: Florence, MA, USA, 1985; ISBN 0684841460. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.L.; Flanagan, W.G. Creating Competitive Advantage: Give Customers a Reason to Choose You over Your Competitors; Currency/Doubleday: New York, NY, USA, 2006; ISBN 9780385517096. [Google Scholar]

- Tanwar, R. Porter’s Generic Competitive Strategies. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 15, 2319–7668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.-C.; Lin, C.-H.; Chu, Y.-C. Types of Competitive Advantage and Analysis. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, N.; Piercy, N. Competitive Advantage, Quality Strategy and the Role of Marketing. Br. J. Manag. 1996, 7, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelčić, S. Managing Service Quality to Gain Competitive Advantage in Retail Environment. TEM J. 2014, 3, 181–186. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J.D.; William, Q.J. Total Quality Management Implementation and Competitive Advantage: The Role of Structural Control and Exploration. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 1580168. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X. The Relationship between Manufacturing and Service Provision in Operations Management. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2009, 4, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.M. The Resource-Based Theory of Competitive Advantage: Implications for Strategy Formulation. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1991, 33, 114–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maury, B. Sustainable competitive advantage and profitability persistence: Sources versus outcomes for assessing advantage. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 84, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuncoro, W.; Suriani, W.O. Achieving sustainable competitive advantage through product innovation and market driving. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2017, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Švárová, M.; Vrchota, J. Influence of Competitive Advantage on Formulation Business Strategy. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2014, 12, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, V.H.; Foo, A.T.L.; Leong, L.Y.; Ooi, K.B. Can competitive advantage be achieved through knowledge management? A case study on SMEs. Expert Syst. Appl. 2016, 65, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, M.F.; Costa, C.E.; de Angelo, C.F.; Moraes, W.F.A. de Perceived competitive advantage of soccer clubs: A study based on the resource-based view. RAUSP Manag. J. 2018, 53, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitson, M.; Kitson, M.; Martin, R.O.N.; Tyler, P. Regional Competitiveness: An Elusive Yet Key Concept? Reg. Stud. 2004, 38, 991–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śmigielska, G. A business case for sustainable development. CES Work. Pap. 2018, 10, 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, V.; Jones, E.; Venkatesan, R.; Leone, R.P. Is Market Orientation a Source of Sustainable Competitive Advantage or Simply the Cost of Competing? J. Mark. 2011, 75, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duschek, S. Inter-Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. Manag. Rev. 2004, 15, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Real, J.L.; Gázquez-Abad, J.C.; Esteban-Millat, I.; Martínez-López, F.J. Betting exclusively for private labels: Could it have negative consequences for retailers? Span. J. Mark. ESIC 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres, L. Semi-Structured Interview. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, R.; Holland, J. What Is Qualitative Interviewing; A&C Black: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 1849668027. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, S.; Brinkmann, S. InterViews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; ISBN 0761925414. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, C. Semi-Structured Interviews. Interview Tech. UX Pract. 2014, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A.; Osborn, M. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. In Research Methods in Psychology; Breakwell, G.M., Fife-Schaw, C., Smith, J.A., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2006; pp. 53–80. [Google Scholar]

- Kallio, H.; Pietila, A.; Johnson, M.; Kangasniemi, M. Systematic Methodological Review: Developing a Framework for a Qualitative SemiStructured Interview Guide; University of Salford: Manchester, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Leavy, P.; Brinkmann, S. Unstructured and Semi-Structured Interviewing. In The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Barriball, L.K.; While, A. Collecting data using a semi-structured interview: A discussion paper. J. Adv. Nurs. 1994, 19, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis-Beck, M.; Bryman, A.; Futing Liao, T. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Social Science Research Methods; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; ISBN 9780761923633. [Google Scholar]

- McKechnie, L.E.F. Observation Schedule. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- The Civil Law. Dz.U. 2018 poz. 1025 OBWIESZCZENIE; Internetowy System Aktów Prawnych (Internet Law System): Warsaw, Poland, 2018; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Największe Sieci Handlowe w Polsce w 2017 r. Dyskonty Deklasują Konkurencję. Available online: https://businessinsider.com.pl/twoje-pieniadze/najwieksze-sieci-handlowe-w-polsce-w-2017-roku/xc8lq0z (accessed on 9 June 2018).

- 10 Sieci Handlowych z Największym Udziałem w Polskim Rynku FMCG [GRAFIKA]. Available online: https://wiadomosci.stockwatch.pl/10-sieci-handlowych-z-najwiekszym-udzialem-w-polskim-rynku-fmcg-grafika,analizy,183639 (accessed on 9 June 2018).

- Garczarek-Bąk, U. Przegląd marek własnych sieci handlowych w Polsce i na świecie Retailers â€TM private label review in Poland and worldwide. Marketing i Rynek 2016, 2–14. Available online: http://www.marketingirynek.pl/files/1276809751/file/garczarek_mir_9_2016.pdf (accessed on 4 July 2018).

- Carrefour. Carrefour Annual Financial Report 2016. Available online: http://www.carrefour.com/sites/default/files/carrefour_-_2017_annual_report.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2018).

- Auchan. Auchan Annual Financial Report Auchan Holding 2016. Available online: https://www.auchan-holding.com/uploads/files/modules/results/1504611432_59ae8c68d5036.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2018).

- Jeronimo Martins. Annual Report 2016. Available online: https://zoom-in-2016.jeronimomartins.com/wp-content/uploads/JM2016_Integral_en.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2018).

- BioPlanet. Bio Planet Product Catalogue 2016. Available online: https://bioplanet.pl/materialy-do-pobrania?path=Ulotki+produktowe (accessed on 25 February 2018).

- Symbio. Symbio Annual Report 2017. Available online: http://www.symbio.pl/raport-roczny-za-rok-2017 (accessed on 25 February 2018).

- Chabowski, B.R.; Mena, J.A.; Gonzalez-Padron, T.L. The structure of sustainability research in marketing, 1958–2008: A basis for future research opportunities. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P. Evolving sustainably: A longitudinal study of corporate sustainable development. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, W.E.; Sinkula, J.M. Environmental Marketing Strategy and Firm Performance: Effects on New Product Performance and Market Share. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2005, 33, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boboc, D.; Ariciu, A.L.; Ion, R.A. Sustainable consumption: Analysis of consumers’ perceptions about using private brands in food retail. Sustainability 2015, 7, 9293–9309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Polish Bank National Polish Bank—Internetowy Serwis Informacyjny. Available online: http://www.nbp.pl/home.aspx?navid=archa&c=/ascx/tabarch.ascx&n=a251z171229 (accessed on 5 June 2018).

- Aouina Mejri, C.; Bhatli, D. CSR: Consumer responses to the social quality of private labels. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2014, 21, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Category | Scope of Topics |

|---|---|

| Topic Category | Organic Food |

| Main categories | (1) Retail chain policy in the field of organic food (2) Factors influencing the introduction of organic food (3) Share of organic food in total sales (4) Availability and quality of organic food (5) Environment and competition (6) Marketing strategies (7) Private labels—detailed analysis for the purpose of this study (8) Promotion (9) Financial situation (10) Risk factors (11) Perspectives of development |

| Organic Products Categories: | Information: | |

|---|---|---|

| Assortment Analysis | (1) sugar

(2) ketchup, mayonnaise, mustard (3) cereal bars and oatmeal cookies (4) flour (5) rice (6) barley, groats, and brans (7) dried fruits and nuts (8) organic preserves (9) canned vegetables and fruits (10) coffee (11) tea (12) milk and milk drinks (13) cheeses (14) butter (15) rice, soy, and oat drinks (16) oils (17) pasta (18) syrups (maple, date) (19) crunchy, muesli, and rolled cereals (20) honey (21) jams (22) superfood (23) legumes | 1. number of food product items available under PLs

2. number of organic products available under producer brands 3. number of organic products available under OPLs 4. number of categories with organic products 5. number of product items per category |

| Organic Products: | Product Prices for: | |

| Price analysis |

| 1. organic imported brands

2. organic producer brands 3. organic PLs 4. organic discount PLs 5. nonorganic PLs (premium) 6. nonorganic PLs (economy) 7. nonorganic discount PLs |

| Contributors to the CA | |

|---|---|

| PLs-based competitive advantage |

|

| Assortment-based competitive advantage |

|

| Organic-attributes-based competitive advantage |

|

| Sustainability-based competitive advantage |

|

| Price-related competitive advantage |

|

| Retailer-based competitive advantage |

|

| Name of the OPLs | Description of the OPLs |

|---|---|

| Carrefour Bio |

|

| Auchanbio |

|

| Tesco Organic |

|

| Bio Organic |

|

| goBio |

|

| Type of Enterprise | Enterprise | Type of Products and PLs | Total Product Items | Number of Categories | Product Items Per Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retailer | Carrefour | food products under PLs | 203 | 19 | 10.7 |

| organic products under producer brands | 274 | 18 | 15.2 | ||

| organic products under PLs | 30 | 13 | 2.3 | ||

| Auchan | food products under PLs | 219 | 16 | 13.7 | |

| organic products under producer brands | 193 | 17 | 11.4 | ||

| organic products under PLs | 22 | 12 | 1.8 | ||

| Tesco | food products under PLs | 401 | 17 | 23.6 | |

| organic products under producer brands | 105 | 13 | 8.1 | ||

| organic products under PLs | 26 | 12 | 2.2 | ||

| Discount | Biedronka | food products under PLs | 257 | 17 | 15.1 |

| organic products under producer brands | 8 | 1 | 8.0 | ||

| organic products under PLs | 26 | 12 | 2.2 | ||

| Lidl | food products under PLs | 352 | 16 | 22.0 | |

| organic products under producer brands | 9 | 5 | 1.8 | ||

| organic products under PLs | 29 | 11 | 2.6 | ||

| Producer and distributor | BioPlanet | food products under PLs | 1539 | 19 | 81.0 |

| organic products under producer brands | 270 | 10 | 27.0 | ||

| Producer | Symbio | organic products under producer brands | 198 | 12 | 16.5 |

| BioBabalski | organic products under producer brands | 60 | 5 | 12.0 |

| Organic Product Categories | Symbio | Bio-Babalski | Bio Planet | Carrefour | Auchan | Tesco | Biedronka | Lidl | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | O | O | OPLs | PLs | O | OPLs | PLs | O | OPLs | PLs | O | OPLs | PLs | O | OPLs | PLs | O | OPLs | |

| sugar | 1 | 22 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||

| ketchup, mayonnaise, mustard | 3 | 23 | 10 | 6 | 3 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 13 | 13 | 9 | ||||||||

| cereal bars and oatmeal cookies | 9 | 141 | 23 | 28 | 9 | 14 | 11 | 1 | 21 | 7 | 2 | 37 | 2 | 41 | |||||

| flour | 29 | 17 | 82 | 33 | 2 | 21 | 3 | 16 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| barley, groats, and brans | 22 | 15 | 61 | 26 | 5 | 15 | 2 | 8 | 9 | 4 | 37 | 4 | 10 | 6 | 2 | 2 | |||

| rice | 7 | 37 | 19 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 13 | 6 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 1 | ||||

| dried fruits and nuts | 56 | 137 | 67 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| organic preserves | 15 | 59 | 15 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 2 | ||||||||||

| canned vegetables and fruits | 146 | 20 | 15 | 2 | 11 | 10 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 12 | ||||||

| coffee | 1 | 85 | 7 | 15 | 2 | 47 | 5 | 1 | 28 | 4 | 18 | 1 | 21 | 1 | |||||

| tea | 273 | 15 | 35 | 2 | 35 | 21 | 0 | 77 | 0 | 50 | 6 | 55 | |||||||

| milk and milk drinks | 14 | 34 | 1 | 13 | 43 | 45 | 10 | 26 | 8 | 2 | 60 | 5 | |||||||

| cheeses | 38 | 29 | 1 | 31 | 11 | 64 | 38 | 1 | 68 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| butter | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 9 | 7 | 5 | 1 | |||||||||||

| rice, soy, and oat drinks | 5 | 3 | 5 | 3 | |||||||||||||||

| oils | 7 | 101 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 10 | 20 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 10 | 4 | ||||

| pasta | 12 | 19 | 103 | 18 | 30 | 20 | 7 | 5 | 36 | 17 | 1 | 20 | 3 | 17 | 1 | ||||

| syrups (maple, date) | 44 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 20 | 3 | |||||||||||||

| crunchy, muesli, and rolled cereals | 25 | 8 | 98 | 61 | 20 | 14 | 1 | 20 | 5 | ||||||||||

| honey | 36 | 4 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||

| jams | 15 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 28 | 4 | 2 | 16 | 3 | ||||||||||

| superfood | 19 | 18 | |||||||||||||||||

| legumes | 12 | 70 | 34 | ||||||||||||||||

| Popular Organic Products under OPLs Available at Particular Retailers | |

|---|---|

| Organic products under OPLs available at all of the analyzed retailers | basmati rice, long-grain rice coffee sunflower oil, rapeseed oil |

| Specific Organic Products under OPLs Available at Particular Retailers | |

| … at Carrefour as Carrefour Bio | canned tomatoes, canned green lentils

bulgur, French mustard apple mousse, apple–pear mousse, apple–banana mousse, apple–peach mousse |

| … at Auchan as Auchanbio | tomato sauce, thyme natural soy drink, chocolate soy drink, soy drink with calcium oat drink, almond drink spelt pasta, rye pasta orange jam, apricot–strawberry jam |

| … at Tesco as Tesco Organic | salty spelt sticks, salty spelt pretzels, dried tomatoes, soya rice–almond drink, rice drink, oat drink |

| … at Lidl as Bio Organic | linen flour bread flour muesli |

| … at Biedronka as goBio | frozen strawberries tomato passata, grenadine drink coconut oil, hummus, green tea |

| Enterprises | Brands | Products | PLN 1/ Per kg | Average Price | Price Difference 2/ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic Imported Brands | |||||

| BioPlanet | Amaizin | basmati quick boiled | 26.68 | 26.53 | +77.1% |

| BioPlanet | Davert | wholegrain | 26.38 | ||

| Organic Producer Brands | |||||

| Symbio | Symbio | basmati white | 25.98 | 18.38 | +22.7% |

| Symbio | Symbio | basmati brown | 23.98 | ||

| BioPlanet | BioPlanet | long-grain brown | 13.10 | ||

| BioPlanet | BioPlanet | long-grain white | 12.54 | ||

| BioPlanet | BioPlanet | basmati wholegrain | 16.88 | ||

| BioPlanet | BioPlanet | basmati white | 17.78 | ||

| Organic Private Labels | |||||

| Carrefour | Carrefour BIO | basmati white | 14.98 | 14.98 | 100% |

| Auchan | AuchanBio | long-grain brown | 14.98 | ||

| Tesco | Tesco Organic | basmati white | 14.98 | ||

| Organic Discount Private Labels | |||||

| Jeronimo Martins | goBio | basmati white | 11.98 | 11.98 | −20.0% |

| Lidl | Bio Organic | long-grain | 11.98 | ||

| Non-organic Private Labels | |||||

| Carrefour | Carrefour | basmati white | 9.98 | 5.49 | −63.3% |

| Carrefour | Carrefour | long-grain | 5.38 | ||

| Auchan | Auchan | long-grain | 2.78 | ||

| Tesco | Tesco | basmati white | 6.98 | ||

| Tesco | Tesco | long-grain | 3.98 | ||

| Non-organic Private Labels (economy) | |||||

| Auchan | Auchan economy | long-grain | 3.85 | 3.32 | −77.8% |

| Tesco | Tesco Value | long-grain | 2.79 | ||

| Non-organic Discount Private Labels | |||||

| Jeronimo Martins | Supreme | long-grain | 7.13 | 7.13 | −52.4% |

| Enterprises | Brands | PLN 1/ Per kg | Average Price | Price Difference 2/ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic Imported Brands | ||||

| BioPlanet | Cafe Michel | 87.08 | 88.97 | +29.3% |

| BioPlanet | Alce Nero | 83.20 | ||

| BioPlanet | Oxfam | 80.96 | ||

| BioPlanet | Lebensbaum | 98.48 | ||

| BioPlanet | Ale Cafe | 105.48 | ||

| BioPlanet | Alternativa | 78.60 | ||

| Organic Private Labels | ||||

| Carrefour | Carrefour BIO | 79.96 | 68.81 | 100% |

| Auchan | AuchanBio | 55.96 | ||

| Organic Discount Private Labels | ||||

| Jeronimo Martins | goBio | 39.98 | 39.98 | −41.9% |

| Lidl | Bio Organic | 39.99 | ||

| Non-organic Private Labels (premium) | ||||

| Carrefour | Carrefour | 43.96 | 48.09 | −30.1% |

| Auchan | Auchan | 43.96 | ||

| Tesco | Tesco Finest | 56.34 | ||

| Non-organic Private Labels (economy) | ||||

| Auchan | Auchan economy | 29.90 | 29.91 | −56.5% |

| Tesco | Tesco Value | 29.93 | ||

| Non-organic Discount Private Labels | ||||

| Jeronimo Martins | Biedronka | 51.96 | 51.96 | −24.5% |

| Enterprises | Brands | Products | PLN 1/ Per Liter | Average Price | Price Difference 2/ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic Imported Brands | |||||

| BioPlanet | Dary Natury | rapeseed oil | 34.56 | 31.01 | +95.4% |

| BioPlanet | Poloniak | rapeseed oil | 31.04 | ||

| BioPlanet | Planette | rapeseed oil | 27.44 | ||

| Organic Private Labels | |||||

| Carrefour | Carrefour BIO | rapeseed oil | 18.65 | 15.87 | 100% |

| Auchan | AuchanBio | rapeseed oil | 15.99 | ||

| Tesco | Tesco Organic | rapeseed oil | 12.99 | ||

| Non-organic Private Labels | |||||

| Auchan | Auchan | rapeseed oil | 4.99 | 4.54 | −71.4% |

| Tesco | Tesco | rapeseed oil | 5.09 | ||

| Organic Imported Brands | |||||

| BioPlanet | Planette | sunflower oil | 23.64 | 22,48 | +35.0% |

| BioPlanet | Planette | sunflower oil | 21.32 | ||

| Organic Private Labels | |||||

| Carrefour | Carrefour BIO | sunflower oil | 18.65 | 16.65 | 100% |

| Auchan | AuchanBio | sunflower oil | 14.65 | ||

| Non-organic Private Labels | |||||

| Auchan | Auchan | sunflower oil | 4.68 | 4.69 | −71.8% |

| Tesco | Tesco | sunflower oil | 4.69 | ||

| Non-organic Private Labels (economy) | |||||

| Tesco | Tesco Value | sunflower oil | 4.69 | 4.69 | −71.8% |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Górska-Warsewicz, H.; Żakowska-Biemans, S.; Czeczotko, M.; Świątkowska, M.; Stangierska, D.; Świstak, E.; Bobola, A.; Szlachciuk, J.; Krajewski, K. Organic Private Labels as Sources of Competitive Advantage—The Case of International Retailers Operating on the Polish Market. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2338. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072338

Górska-Warsewicz H, Żakowska-Biemans S, Czeczotko M, Świątkowska M, Stangierska D, Świstak E, Bobola A, Szlachciuk J, Krajewski K. Organic Private Labels as Sources of Competitive Advantage—The Case of International Retailers Operating on the Polish Market. Sustainability. 2018; 10(7):2338. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072338

Chicago/Turabian StyleGórska-Warsewicz, Hanna, Sylwia Żakowska-Biemans, Maksymilian Czeczotko, Monika Świątkowska, Dagmara Stangierska, Ewa Świstak, Agnieszka Bobola, Julita Szlachciuk, and Karol Krajewski. 2018. "Organic Private Labels as Sources of Competitive Advantage—The Case of International Retailers Operating on the Polish Market" Sustainability 10, no. 7: 2338. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072338

APA StyleGórska-Warsewicz, H., Żakowska-Biemans, S., Czeczotko, M., Świątkowska, M., Stangierska, D., Świstak, E., Bobola, A., Szlachciuk, J., & Krajewski, K. (2018). Organic Private Labels as Sources of Competitive Advantage—The Case of International Retailers Operating on the Polish Market. Sustainability, 10(7), 2338. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072338