1. Introduction

The field of cultural and landscape heritage involves elements of a diverse nature and meaning—often defined and legislated by both national and international standards—and includes both fixed and movable, tangible and intangible assets; generally speaking, systems “of artistic, archaeological, and ethno-anthropological interest” [

1], and that are representative of specific cultures and territories. A heritage encompasses a wide range of elements, of a rather broad nature: paintings, sculptures, monuments, books, documents, archives, buildings, and villas, but also public squares, historic centres, entire cities, landscapes, or even aspects of the tangible local culture, religious or pagan traditions, chants, etc. The scope of discussion is thus not only physical or abstract heritage, whether fixed or movable, but even one-of-a-kind or common items [

1,

2], following a discussion on the topic that may lend itself to multiple interpretations. It is interesting to highlight how Italy, the country boasting the highest number of United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Sites [

3], represents an exceptional treasure chest of cultural heritage at a global level. This is why the Italian nation has a strong interest in the topic; a discussion on actions to safeguard and promote heritage is urgent and unavoidable. In particular, the year 2018—European Year of Cultural Heritage—makes a reflection on the topic even more current.

In 2005–2007, inter-university research funded by MIUR—Italian Ministry of Education, University, and Research named d.CULT was conducted and focused on the design and promotion of cultural heritage: strategies, tools, and project methods. This MIUR PRIN—project of national relevance—had the purpose of launching a national debate on the basis of Decree Law no. 42 “Code for cultural and landscape heritage” issued on 22 January 2004, with the purpose of dealing with the topic as exhaustively as possible and legislating actions for the safeguard of cultural resources. It saw eight research and design units from Italian universities working to analyse the relationship between design and cultural heritage, and define the role of design in the processes for promotion of such cultural heritage [

4]. The debate tended especially to highlight the need to consider the topic of enhancement of cultural heritage, in terms of better promotion and an easier fruition, as an equally important and necessary field to protection and safeguarding actions.

“The link between cultural heritage and the purposes and practices related to design is an extremely recent conquest. It owes its equally young success to the widespread awareness that, as well as being an area that is extremely dense with resources of such type, our country [Italy-Ed.] is also a place strongly in need of an at least revised sensitivity with regard to the use of the cultural property.”

Starting from a socio-cognitive epistemological analysis (in terms of the relationship between design, value, and cultural heritage), the research outlined strategies, tools, and project methods that, over time, have represented the basis for more precise analyses and field experimentation nationwide, in sectors including art, architectural, and environmental excellence, as well as regional material culture.

With the starting point of shared know-how deriving from experiences developed in national research (analyses, case studies, field research), a group of design specialists at the Politecnico di Torino has, in fact, approached the topic of promotion of cultural and landscape heritage of the territory with an increasingly strong confidence and methodology, by establishing cooperation agreements—with institutions, museums, and other entities—that are ongoing and have generated noteworthy results.

On the basis of such experience, lasting for over 10 years, the authors of this article have, in fact, developed an approach consisting of methods and tools that have been outlined in a recent international publication [

5], of which the key elements will be synthetically mentioned, and the validity of which will be proven through an outline of the most recent case of implementation, namely a museum/territory merchandising operation, which is the focus of this article.

The research carried out by d.CULT proved how design—intended as a craft for the development of innovative, useful, and functional products and services, equipped with perception capabilities and carriers of conveyable values—finds a natural vocation at the service of cultural heritage, which is an environment in which the promotion of the cultural property [

6] has a fundamental role in the survival and development of the property itself.

Design is, in fact, a strategic tool for a focus on approaches and solutions with the ability to promote cultural heritage (as described by Monterosso for the mineral museum of Trabia-Tallarita in Sicily [

7]) in terms of improving its enjoyment, strengthening its identity, and increasing its key role in the local economy. Museums and heritage sites, in fact, can produce monetary values for other economic actors by creating additional jobs and commercial revenue, particularly in the tourist and restaurant industries [

8].

The identity and cultural peculiarities of a territory—from its historical artistic heritage to its environmental resources, as well as its local material culture—indeed represent a system of values that require, along with suitable safeguarding actions, particular attention to promotional and valorisation strategies.

In particular, design applied to cultural heritage has the ability to translate the intangible nature [

9,

10,

11] of a message as well as its implicit cultural value, and make them tangible and comprehensible through meaningful products, or services, or experiences that coherently reference the same galaxies of values. The “Histoire de Paris” plaques by Philippe Starck, i.e., the set of information plaques scattered throughout the city of Paris in front of various Parisian monuments, are one example of how design can convey an intangible value—in this case, the Latin motto of the City of Paris, “Fluctuat nec mergitur” (“battered by the waves, but never capsized”), recalling the vessel of the water merchants of Paris—into tangible objects, through the most appropriate choice of shape, similar to an oar, and the colours (for a complete census of the Histoire de Paris plaques project:

www.openplaques.org). Through the mediation process controlled by design, the cultural resource takes on a modern significance that target users of different cultural backgrounds are able to perceive.

Design, therefore, carries out an action that is not only “useful” (in terms of development of useful products and services), but also an action of “social responsibility”, in that it contributes to the focalization and communication of universal cultural values through a language that is accessible to all target markets [

5].

Moving slightly beyond such a concept, one can also state that the ability to make the system of values defining cultural property popular and accessible is an essential condition for its very existence (i.e., “I recognize it as such, therefore it exists”).

Museum Merchandise: A Literature Review of Case Studies and of the Historical Background

A literature review of case studies and of the historical background on museum merchandise was performed in order to contextualize the topic. As suggested in literature [

12], merchandising can prolong the museum experience and, more in detail, can improve the traditional educational mission of the museum through its merchandise selection [

13]. Already in 2000, Theobald [

14] proposed the educational role of a museum shop, in order to contribute to the educational purpose of the museum.

As mentioned [

15], museum merchandise has been present for a long time, first of all in the United States. For example, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, that can be considered an excellence case study for museum merchandising, has included editorial activity and merchandising since its foundation in 1870: in fact, in 1871 the museum decided that the masterpieces of ancient masters should be reproduced for sale (c.f. Ugo La Pietra Reproduction). Afterwards, museums in Europe and elsewhere followed the example of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In Italy, for the MiBAC, Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities, the Ronchey law paves the way for a new system of selling both products and the image of museums in order to promote culture through objects and their representations or reproductions. The law introduces the concept of “cultural memory”, which is not and should not be transferred into a mere souvenir [

16].

Moreover, an important aspect to be considered in order to increase the museum merchandising design is that the bookshop/museum store turnover is constantly growing; furthermore, as suggested by Mauri and Cirrincione [

17], the museum experience can be enriched and intensified, prolonging itself in an indefinite time, also thanks to the museum shops: “the merchandising covers a share that varies between 30% and 50% of book sales, depending on the type of museum and exhibition” [

16]. Museums, in fact, acquired a new role: as a business [

18], they must be able to disseminate culture and collections and also be self-financing, thanks to their shops.

2. Discussion about Design Methods. Previous Experiences and Epistemological Definition of Design for Cultural Heritage

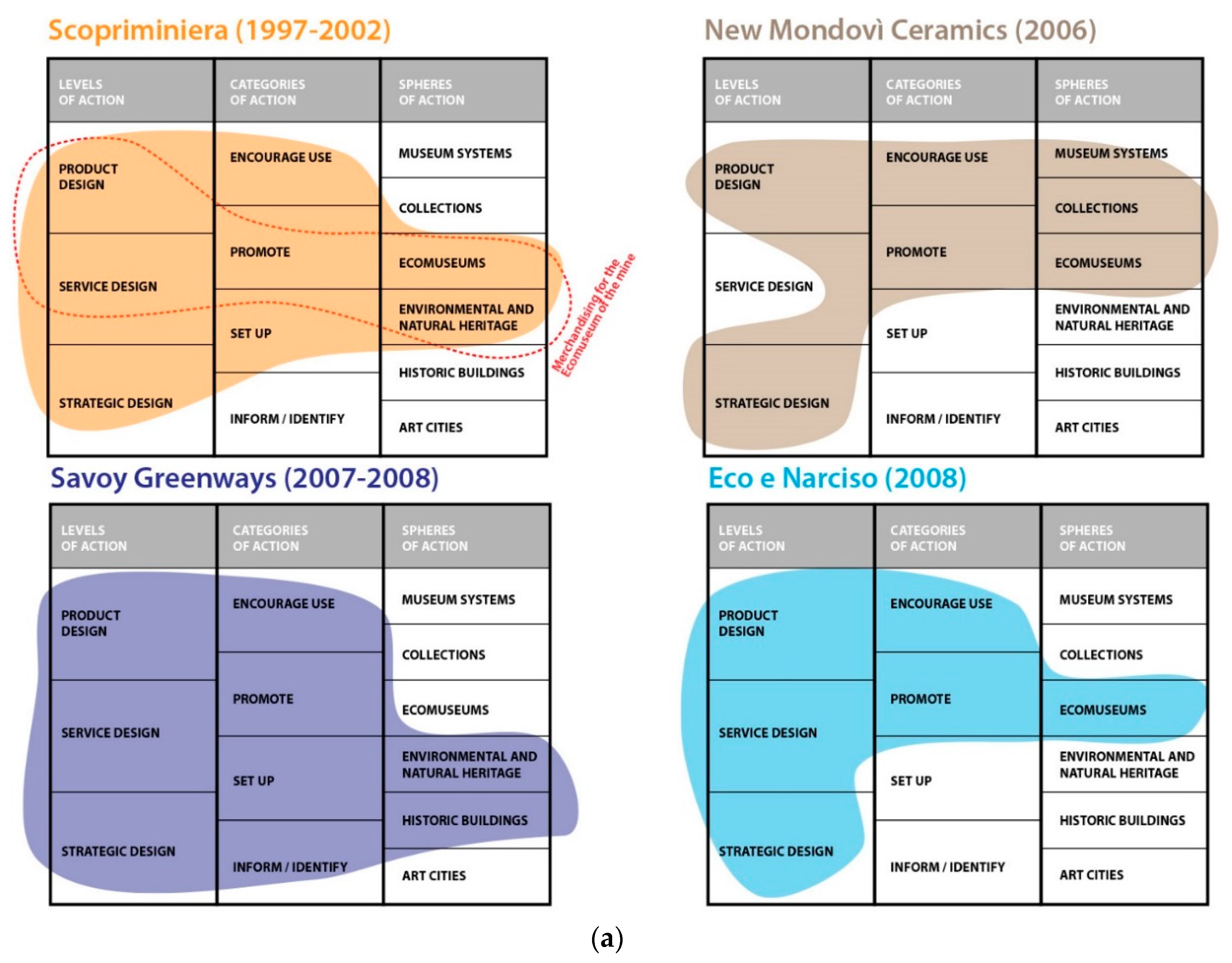

Building on the aforementioned foundations defined by the authors of this article throughout the years with some past research experiences, an approach to the topic that consists of a multi-level classification and a set of cultural tools that may help those operating in the design sector have a better picture of the topic of design applied to cultural heritage, defining an epistemological–methodological perimeter, will be described thereinafter. Some of the previous experiences in this context are, for example, Scopriminiera (project dedicated to the conversion of an abandoned talc mine in Prali (To) for education and tourism; this created an articulated and widespread ecomuseum, which comprises the Mine Museum, the Mine Tour, the Miner’s Canteen, the Study Centre and mountain itineraries, service structures.) [

19]; New Mondovì Ceramics (research and didactic operation developed in partnership between Mondovì Council for Culture and Politecnico di Torino—Industrial Design. This involved 160 tutored students exploring the possible typological, functional and expressive directions with which Mondovì ceramics was called upon to face in its renewal.) [

20]; Savoy Greenways (project developed in collaboration between Politecnico di Torino—Design and Finpiemonte, the financing body of the Piedmont Region, for the definition of a tourist proposal aimed at creating a cycling circuit capable of connecting the “Savoy Residences” within Piedmont.) [

21]; Eco e Narciso (during the 2008 Torino World Design Capital, the cultural show “Eco e Narciso” asked five international design schools (Royal College of Art London, NABA Milan, Design Academy in Eindhoven, Konstfack Stockholm, Politecnico di Torino) to reinterpret the main processes and products of material culture in the province’s ecomuseums: water, clay, cotton, talc, stone (“Rorà stone” developed by Politecnico di Torino).) [

22]; Materialmente (research and design activity for the development of merchandising and service products for the system of Royal Piedmontese Residences, made by craftsmen within the region. A project developed in collaboration with Confartigianato Torino, a local trade association which has been experimenting new ways of sustaining its members for years.) [

23]; Savoir Bois (project aimed at enhancing the wood chain in the light artisan-processing sector in the Piedmont area, for the production of outdoor furnishings conceived in compliance with the principles for the promotion of local resources, linguistic contextuality, and pursuit of the installation of a widespread uniform system of identifying urban furniture throughout the area. The project was realized in collaboration between Politecnico di Torino, Comunità Montana Valli del Monviso, and the local craft enterprises.) [

24]. In this regard, see

Figure 1a,b, which highlights the research carried out in relation to these tools, described more in depth in the next paragraphs.

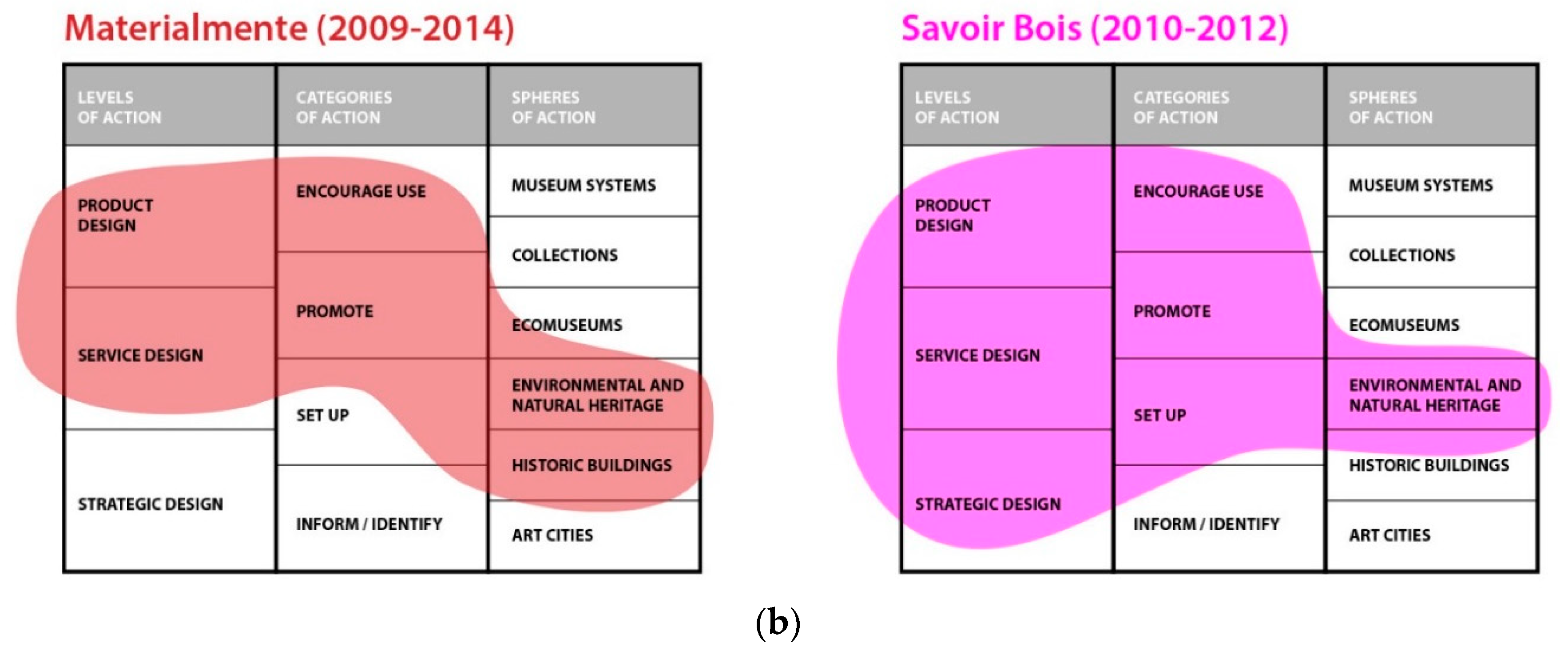

2.1. The Three Interpretation Criteria for Cultural Heritage Design

The method presented originates from the evidence that design for cultural heritage activity may essentially be categorized following three main interpretation criteria, schematized in

Figure 2, specifically: (i) it may be included among a series of recurring “spheres of action” (cf.

Section 2.1.1), corresponding to different types of cultural heritage; (ii) it is applicable through specific “categories of action” (cf.

Section 2.1.2); (iii) it develops on different “levels of action” (cf.

Section 2.1.3). Therefore, it avails itself of three cultural tools (cf.

Section 2.2), namely: (i) the “scenario analysis”; (ii) the “selection of reference points” and (iii) the “shared design” with the parties involved. The originality of this methodology lies in being adaptable and re-configurable, in order to better fit the specific needs of the cultural heritage site, by acting on interpretation criteria and cultural tools.

2.1.1. Spheres of Action

We may include among spheres of action the contexts that require the development of specific products or services, such as those related to the enjoyment of locations or to mobility, accessibility, narration etc.; or more general strategies in support and for the orientation of local policies. These are just a few of the fields of operation of design for cultural heritage, but are certainly the most frequent, and stimulate a number of possible outlets. We shall thus mention the following:

Museum systems, which are par excellence locations/containers of culture;

The collections exhibited therein, namely artworks and other creative works presented in temporary or permanent exhibitions;

Ecomuseums: sites specifically designed to recover the meaning and history of a location, whose identity is based upon the territory itself and the community living in it [

25];

Environmental and natural heritage, namely historic national parks, theme-based itineraries, natural reserves, and portions of the territory that have a recognized historical or landscape value;

Historic buildings with a particular architectural value and are a witness of the area and its social, political, and cultural history;

Art cities: sites that are steeped in unique historic, architectural, and artistic witnesses, which are often targeted by mass—and not always sustainable—tourism.

2.1.2 Categories of Action

The different “ways” in which design for cultural heritage expresses itself are a reflection of the cultural responsiveness and project flexibility that the topic calls for. They intertwine with the aforementioned project elements and, as we shall see thereinafter, apply to different “levels of operation”, thus creating a system of tools and practices that makes design for cultural heritage a true “art within the art”. We therefore choose to mention the following:

Encourage use: to develop systems and products to facilitate access to exhibition areas and areas of cultural interest. This set of actions involves infrastructure and services for transportation and accessibility, museum cards, rest/refreshment areas, etc.

Set up: products for functional setup of local areas of excellence and museum systems (development of exhibition setup systems, ad hoc furnishings, accessories, curtains and tablecloths for inside food courts, point-of-sale (POS) displays for bookshops, display cases for exhibition rooms and their related lighting systems, labelling and information panel systems, etc.);

Promote: systems for the communication and promotion of cultural sites and collections (brochures, posters, dedicated merchandise, advertisement campaigns, websites, etc.);

Inform, identify: systems and products for information and communication of cultural heritage and events (e.g., maps, display cases, flyers, labels, totem displays, monument signs, street signs, landmark structures, information centres, web and mobile technology).

2.1.3. Levels of Action

Moving on to the different levels of action at which design operates, one may consider a varied range of implementation including products, services, and strategies, for which design takes on the role of a multi-dimensional operational tool. The three different levels present a wide margin of overlap; in fact, service design often includes product design actions, just like strategic design may involve the development of products and services.

Product Design Level of Action

Given that product design is meant as the design of elements—mostly “physical” elements—with which the user interacts directly, we immediately consider how wide the range of levels may be: from street furniture for the use of city spaces, to accessories for indoor visits (e.g., exhibition walling panels, furniture for rest/refreshment areas, display cases), from communication and mapping elements to the design of elements able to indirectly narrate a location and a context, such as packaging of local products or elements of local merchandise (which will be analysed in depth in the Results section). Even interior design—when developed following certain criteria for use of local resources, revaluation and narration of the material culture, activation of good practices for the re-launch of craft economies—may certainly be included among approaches for the promotion of the territorial system and thus local cultural heritage.

Service Design Level of Action

Service design—the dimension in which the design operation is performed to develop experiences that actively involve the final user, with the purpose of communicating values, meanings, and functions of systems within the area—includes quite different levels of action. It concerns services for the distribution of goods, actions to foster socialization among the locals, digital/analogue systems (e.g., of hypermediated or immersive type [

26]) to communicate the characteristics of the areas (signage apparatus, visual systems to display data, web platforms and apps for virtual access), mobility services (bike-sharing, car-sharing, carpooling, etc.), organized itinerary systems for the promotion of local cultural and environmental heritage and to incentivise tourism (e.g., the tour itinerary of the Valle Germanasca Ecomuseum for the promotion of mining culture, which we shall discuss more in detail later).

Strategic Design Level of Action

Strategic design levels are even broader, as they include design operations with the purpose of establishing an organization between parties involved in a certain territory, each capable of providing added value to the area itself and the people living in it.

This field includes operations aimed at redefining production processes or exchange and relationship modes between parties involved locally, also to generate mutual cooperation (e.g., production line innovation, configuration of cooperative craftsmen communities); actions for the repositioning of specific companies (diversification of production and detection of new markets, process and product upgrade/update, etc.); social innovation actions or operations typical of systemic design, in terms of planning of material, energy, and data flow, which generates new economies for the territory as they shift from one system to the another.

2.2. The Three Cultural Tools for Cultural Heritage Design

As previously stated, and in accordance with the methodology chosen by the design team of the Politecnico di Torino, cultural tools used in design for cultural heritage and material culture, which are focused on the promotion and valorisation of cultural property through the design of new products, services, and strategies (thus applicable to all project levels), mainly include the interlinked context analysis, selection of reference points, and shared design, described as follows:

2.2.1. Scenario Analysis

An accurate and critical study of the historical–cultural–environmental–technological context of reference, summarized in brief.

The function of the context analysis is thus to support the metadesign phase through the selection and highlighting of topic-related information and knowledge. From a methodological perspective, the context analysis developed within the Design modules of the Politecnico di Torino completes and widens the metadesign action of the requirement/performance approach presented by Giuseppe Ciribini, according to which human demands must be translated—in the design phase—to the product requirements corresponding to the final performance features [

27]. The performance-based industrial design philosophy is, in turn, inspired by the quality function deployment (QFD) method developed in Japan already in the 1960s, which was later spread worldwide, and had the final aim of introducing the customer’s basic requirements for a good/service to the design phase. A critical mass of data and references to the topic of discussion are therefore pointed out: social, cultural, and ethical values, but even historical, production-related, and technological knowledge, which will make up a pseudo-database from which to tap into throughout the formulation of the project proposal [

28]. That means that “design must consider the complexity and the variety of the contemporary world and act like a link among different aspects which gravitate around a point of interest” [

29].

2.2.2. Selection of Reference Points

The activity dedicated to the selection, extrapolation, and abstraction of peculiar and distinguishing elements of the context—shapes, colours, materials, technology, uses, behaviours related to the local culture and/or tradition—to be highlighted or to cross-breed with new materials and technology, thus to be adapted (with an historical and social understanding) to new consumption methods [

30,

31].

This selection may be represented as a catalogue of reference points, which designers may draw inspiration from, directly quoting or referencing them. Drawing elements from this catalogue can help in showing the “belonging” of the concept to the set of values of the analysed context. A similar process applied to redesign the Islamic rosette patterns, enhanced by computer-assisted image analysis techniques, is proposed in literature [

32].

2.2.3. Shared Design

The availability of the designer to take part in a joint design with the involved parties (the local community, the craftsman/manufacturing or processing firm, the visitor/end user). The designer’s role is not so much that of responding to the requirements of the context and target users by presenting packaged/closed-ended turnkey projects, but to indicate pathways, as well as focusing on new methods of conceiving a product, new approaches to the process and production line, languages, creation or update of finishing and construction techniques for handcrafted artefacts, introduction of process sustainability, etc. In short, to create open-ended projects, presented in the form of “guidelines” that can be interpreted by the community, always following certain shared rules, namely sustainable manufacturing practices and market contexts in which the end users are directly involved in the cultural action [

33], and allowing citizen and community participation in promotion processes through tools and actions [

34].

Following this necessary epistemological–methodological introduction, we now intend to focus, in particular, on the role of the item of merchandise as an especially interesting field within the design activities for the promotion of cultural heritage.

2.3. Merchandise Design

Merchandise can be considered as one part of a branding strategy, aimed at enhancing the identity of a place, an institution, or a cultural site. The item of merchandise, often the victim of design and manufacturing stereotypes [

16] that lead to it being a souvenir characterised by a “kitsch attitude” [

35,

36], presents room for improvement in contrast to the strategy of the mere application of a logo on globalized objects [

37].

Within a broader strategy for promotion of the cultural property’s contents and identity, merchandise may strongly contribute to the build-up of a non-ephemeral “sense” to the property, and extend the experience over time by condensing the intangible cultural heritage to new, highly meaningful (little) artefacts, at a moderate price and able to convey complex contents in a way that is scientifically adequate and comprehensible to different categories of target users.

In fact, merchandise may be produced for free promotion purposes, often non-contextual and not always useful, at least not something truly needed, in which the product is a means to expose a brand, which is the real objective of the operation (such products are often small consumer goods of little worth, such as caps, t-shirts, key chains, pins, pens, umbrellas, etc.). Merchandise may also be produced for commercial purposes, with the products being functional and designed to promote a brand or cultural resource (the consumer spontaneously decides to purchase such items).

We thus highlight the opportunity to develop items of merchandise that are dedicated, specifically designed for a particular site, and not consumerist, i.e., not anonymous globalized objects. The new merchandise will result from the previously listed activities (analysis, selection and synthetic re-processing of cultural content and distinguishing features of the heritage to promote, and share the design with the involved parties). The new products have to be “democratic”, in terms of qualitatively reliable, socially and environmentally sustainable and economically affordable to everyone, as pillars of the design discipline [

38]. Furthermore, once brought home, these products may continue to narrate the experience of the visit and extend it. At a small scale and relegated to specific contexts, consciously designed merchandise does exist, and follows a philosophy according to which the product is designed to perform a particular function. Furthermore, it has a meaning which is in context and coherent with the identity that is being promoted, in compliance with a double functional and symbolic attitude [

39]. Well-designed merchandise for cultural heritage must present conveyable cultural contents and make them recognizable, must be representative of the context it originates from, and possibly have a playful dimension as well. Such a product is a valid alternative to promotional merchandise, which is generic, “soulless”, made of little more than logos, and still deeply rooted (and popular) especially in promotional campaigns.

2.3.1. Museum Merchandise

As a sub-category of merchandise for cultural heritage, the products and services (that, depending on the strategy adopted, may have promotional and/or commercial purposes) designed to give an added value to the visit to a show or a museum are defined museum merchandise. It may be considered as a reference point to outline certain key phases of the museum visit experience itself. The first phase is the choice and selection of the show/museum to visit; secondly, there is the visit to the cultural site itself; and finally, there is the phase in which cultural site/museum merchandise finds its place, namely the museum gift shop. Such a final phase may thus turn into a continuation of the visit itself: the purchase of merchandise—when the products are well-designed and coherent with the contents of the show or museum—follows, extends, and completes the visit experienced, which thus “becomes richer and more intense, extending for an indefinite amount of time” [

17].

The purchase of a coherent and good merchandise product can moreover become a way, for visitors characterized by “pro-environmental behaviour”, to participate in economically supporting the cultural heritage site and its values with a small “financial action” [

40].

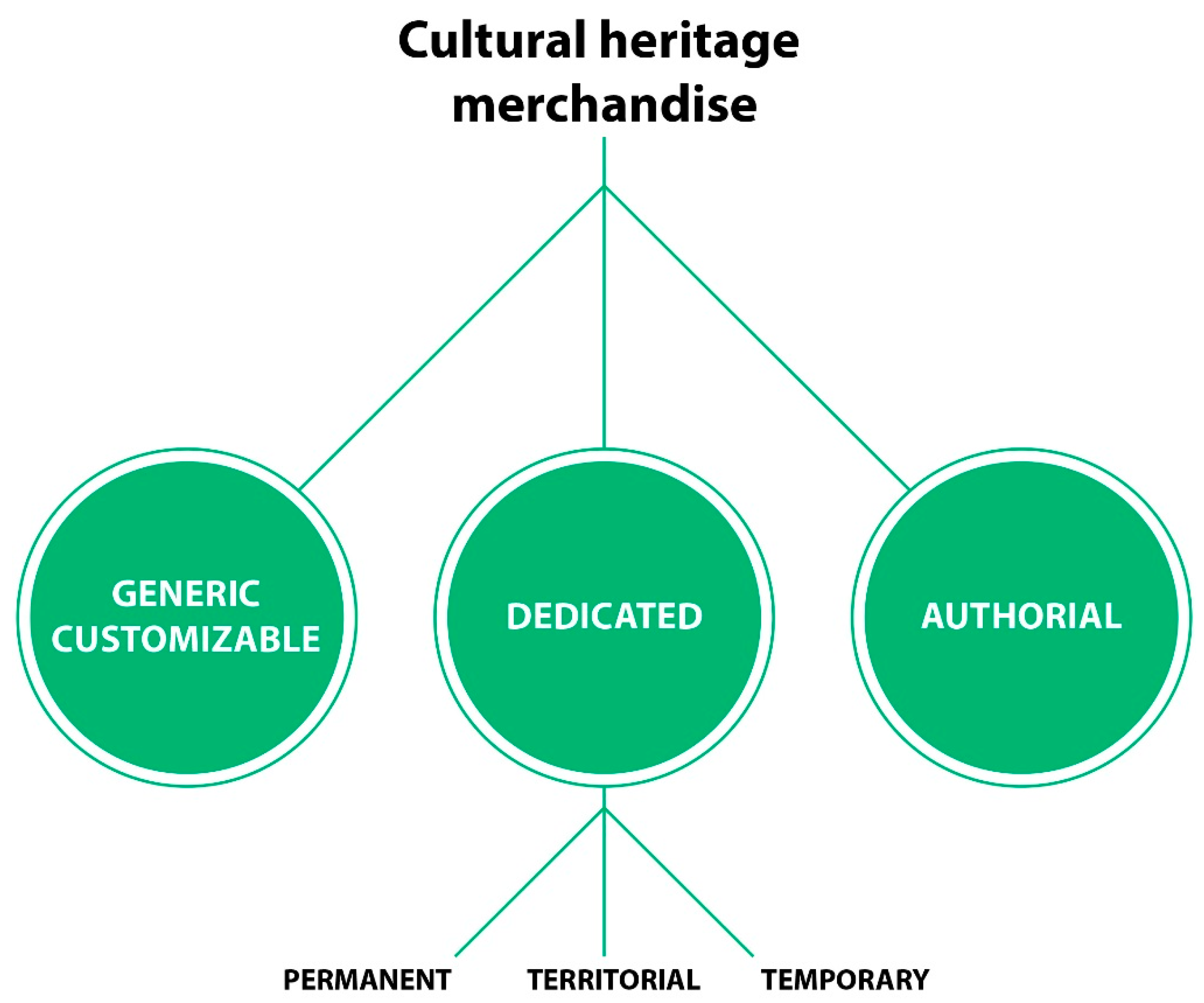

2.3.2. Types of Merchandise for Cultural Heritage—A Possible Classification

Items of merchandise belong to more popular product categories, each satisfying different promotion strategies used by the museum, and to the diverse characteristics of the show (

Figure 3).

We may thus classify the merchandise as follows: (i) Generic and customisable, namely industrial products of common use that are customised with the museum or institutional logo (e.g., mugs, caps, t-shirts). The communication element relies completely upon the customisation, and the product does not make reference to the cultural heritage promoted in any other way; (ii) Dedicated, namely merchandise that is designed ad hoc for all previously listed spheres of action (art cities, bookshops in museums or permanent/temporary exhibitions, etc.) thus, in detail: permanent dedicated merchandise, namely products sold that are conceived as an expression of the distinguishing traits of the collection, the essence of the museum, or the cultural property itself. This type of merchandise maintains its full meaning and sense when sold within the museum walls or within the cultural and territorial context for which it has been developed; temporary dedicated merchandise, namely product types designed purposely for specific events and temporary museum collections. The artefacts relate to the contents of the show through different types of references (replicas, hints of distinguishing features of the collection, etc.); territorial merchandise, namely dedicated merchandise that is designed with the aim of promoting the characteristics of a local/regional/national territory to which the museum belongs. It may include products that celebrate the area (through references to local art and architecture), or an expression of the tangible culture (handcrafted and artistic local products, local food and wine specialties, etc.); (iii) Authorial, namely objects related to design-oriented functions (household goods, simple and special objects, or products designed by top-notch designers), and not necessarily referencing the location or the museum collections.

In particular, in terms of dedicated merchandising projects, there have been some noteworthy alternative approaches. For example, Ugo La Pietra [

41] focused on specific product types that may be developed taking inspiration from certain recurring design approaches, namely:

The philologically accurate reproduction of the artefacts present in the museum (replicas);

The reproduction of the original artefact following a financial logic (scale models);

Scale-model reproductions made of a different material;

Reproduction of the artefact on a different medium (print on a scarf, engraving on ceramics, etc.);

Reference to distinguishing features or details of the artefacts within different products (conveyance of values), i.e., with a “figurative” approach;

Hint to the artefact: the product has nothing explicitly resembling the artefact, but the project behind it hints to it somehow, i.e., with a “metaphoric” approach.

On the basis of the above classification, it can be stated that the first four approaches, related to the reproduction of the artefact, may be considered correct and effective, although they do not necessarily involve the designer in their development, which is often the domain of the manufacturer. On the other hand, the last two approaches seem more interesting in terms of the interpretation implications they offer, more suited to a designer’s cultural and methodological operation.

But, as every new method proposed in literature must be soon tested with a real application of it into a practical case study, the general theory and mechanisms here proposed, i.e., the three interpretation criteria for cultural heritage design proposed in

Section 2.1 and the three cultural tools for cultural heritage design proposed in

Section 2.2, were applied to a research and didactic activity, with the purpose of experiencing and trying the method in a scientific but also applicative context. This experience represents the practical implementation of this work, and the experience itself, the selected case study, the adopted working method, the results obtained and their evolutions are presented in

Section 3 and discussed, together with the opportunities offered by the method in

Section 4.

3. Practical Implementation. New Merchandise for the Ecomuseo Delle Miniere e Della Valle Germanasca

This section presents a detailed analysis highlighting the results of the previously outlined method and approach, applied to a dedicated design project for the Ecomuseo delle Miniere e della Valle Germanasca (Valle Germanasca and Mine ecomuseum) in Prali (Turin, Italy). This ecomuseum is distinguished by a very rich cultural programme and has had great success in terms of visitors, but with a bookshop offering low-quality merchandise that fails to fully convey the cultural contents of the experience. For this reason, in-depth work on museum merchandise products was much needed, and this opportunity generated the room to apply the previously described method.

3.1. From Theory to Practice: The Ecomuseo Delle Miniere e Della Valle Germanasca and the ‘In Miniera!’ Project

Even if the reconversion of historic buildings as museums is quite frequent, preservation not only of historic buildings and sites, but also of historical plants is necessary not only to attest the technological evolution in relation to the changing ways of life, but also to attest that they can sometimes be re-employed, depending on their typology, through the use of new technological products, taking advantage of their cultural potentiality [

42]. With this aim, since 1998 the Ecomuseo delle Miniere e della Valle Germanasca (about 70 km away from Turin) has been recovering and promoting the rich cultural heritage related to talc extraction (the precious “white of the Alps”). With about 16,000 visitors per year, the museum narrates the mining activity (the technology related to talc extraction, and talc mines building) and the life (traditions, religion, community) of the miners in the Germanasca valley up until the 1960s, when the decline of the mining activity and shutdown of the mines began.

After a long period of economic stagnation, in the 1990s the Comunità Montana (Consortium of Mountain Municipalities) of the valley—also supported by the Politecnico di Torino—had sensed the potential of the cultural and material heritage of the mines, and launched a brainstorming process for possible promotion strategies and services that would distinguish the package.

Through participation in European Union (EU) projects and, thus, thanks to the participation of regional stakeholders and the whole community, and to an accurate management of the complex development process, the initiative enjoyed considerable success. After the creation of ScopriMiniera (“discover the mine”, 1998), which visitors positively responded to from the very start, the package was broadened through different spin-off projects, with the most evident being the second visit itinerary named ScopriAlpi (“discover the Alps”, 2013), especially dedicated to fostering knowledge of minerals and the stratigraphy of the valley.

Following the above described operation criteria (c.f.

Section 2) the design for cultural heritage has been developed involving every level the local community, as the only way to establish a “community co-management framework”, in order to mobilize residents to participate in heritage conservation and enhancement [

43]. Specifically, in coherence with the previously described classification, it has touched upon the following:

different spheres of action (the outdoor part of the museum, the mine itinerary, and the environmental/natural heritage);

different categories of action (promotion, information, and highlighting the most significant elements of the mining culture in an enticing way);

different levels of action: strategic design, to give new value to abandoned mines thanks to a package that was included in the network of European ecomuseums and mining museums (For more details concerning the National Network of Parks and Mineral Museums, see [

44]); service design, to make them accessible and interesting for a diverse target audience (educational workshops for schools, visits led by former miners, special itineraries for mine lovers); and ad hoc product design (outdoor and indoor setups, infrastructure designed for the visit, such as mine trains on-board which visitors travel across the mines, clothing for the visitors, signalling systems, etc.).

In terms of the aforementioned strategic and service design levels of action, the ecomuseum presents a remarkably evolved communication language. During the visit to the museum and mines, the relationship with the visitor hinges on the identification with the miner or explorer (in every aspect including clothing, the journey on the mine train, the miners’ shadows emerging from the talc, and sound effects), though maintaining the scientific nature of the narration.

Indeed, the information collected from its repositories (archives, memories, and stories of witnesses), is evolved in a synthetic and modern fashion, but kept true to its origins thanks to a deeply respectful attitude towards the involved community’s cultural heritage, favouring the choice of realistic mining materials and technology for all its operations (including scaffolding boards, classic mining colours for the trains, stencil-style engraving techniques, etc.). Therefore, the approach had to be standardized even at the product design level of action: this was the foundation of the “In miniera!” (to the mine!) didactic and research project. The operation, in force since 2016–2017, is particularly interesting in that, as well as enriching the visitor experience through new merchandising projects, completes the set of levels of action (cf.

Section 2.1.3) in which the design team of the Politecnico di Torino has already been involved by the Ecomuseum. In fact, among the possible uses of product design, merchandise had not been dealt with before the “In miniera!” initiative. Until the year 2017, the ecomuseum limited itself to offering self-created products, such as “branded” objects (e.g.,

t-shirts, caps, mugs) or products deriving from immediate reference to traditional objects of the valley and the classic mining/mountain world in general, in a simple or even pedestrian version (e.g., a dwarf miner), and transposed to “non-contextual” products such as key chains, knick-knacks, and fridge magnets, manufactured using disparate technologies. With this in mind, the product-merchandising project becomes a pillar of the product design level of action.

The previously described epistemological basis and methodology are then adopted in the operation in question, which is also the most recent operation carried out by the authors of this article in the design of the cultural heritage research field (c.f.

Section 2). As mentioned, the operation was aimed at the creation of a dedicated, geographic area-specific collection of museum merchandise, to be inserted in the bookshop on the occasion of the museum’s 20th anniversary (autumn 2018).

3.2. The Working Method

“In miniera!” was a challenge with a research and education feel, because of the cooperation between the Ecomuseo delle Miniere e della Valle Germanasca and the Politecnico di Torino. The new merchandising project involved about 230 Year 1 design students at the university, in groups of 3 or 4, who worked constantly under the guidance and tutorage of senior lecturers and workshop co-operators, including the authors of this article.

In terms of the working method, the operation adopted the three cultural tools for cultural heritage design previously disclosed (c.f.

Section 2.2). The first phase of the didactic experience involved indeed the scenario analysis, i.e., an analysis of the context of reference of the Ecomuseum. This tool has allowed an interpretation of the historical, social, and cultural context, as well as a technological, market, and buyer framework. Furthermore, it allowed the development of a critical set of environment-specific characteristics (the commissioner identity, the ecomuseum and educational visit worlds, the target market, the state of the market, the social–cultural scenarios in terms of museum experience, as well as the new visit types and customer demands). This phase was followed by the selection of reference points, i.e., an extrapolation of peculiar and distinguishing elements of the mine consisting of iconographic and written documentation produced by the group of lecturers upon agreement with the commissioners. The above informative documentation has represented the reference point for the subsequent design process, and has been a fundamental component in order to outline approaches, solutions, and opportunities with the power to bring a conscious metadesign evolution [

45]. Finally, the sharing design tool was adopted: upon sharing the work environment and its peculiarities by means of in-class presentations and on-site visits, the students have been invited to develop highly significant and uncommon design proposals. Different target audiences and financial means have been taken into account, based on the current Ecomuseums targets: (i) groups of children and students; (ii) families, in particular on weekends and holidays and (iii) Italian and foreign mineralogy or mountain lovers. The purchasing power and tendency to spend reported by the ecomuseum bookshop are quite low, ranging from 5 euros for children/young adults on field trips, to 15 euros for mineralogy/mountain lovers. This information was also considered in the concept development.

The design students were invited to use, for their proposals, materials and processing techniques with the potential to promote talc as the protagonist of the narration and visit. The “figurative”, i.e., giving a hint to the artefact, or “metaphoric”, i.e., providing a reference to the artefact, design approaches were preferred among those by La Pietra [

41] (c.f.

Section 2.3.2), in order to capitalize on references and witnesses to present products that are new but respect the past, and are philologically coherent with the Ecomuseum’s message and mission.

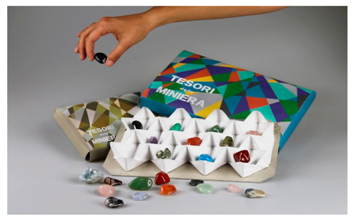

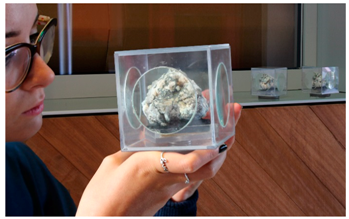

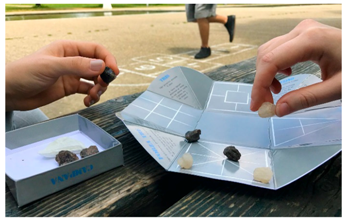

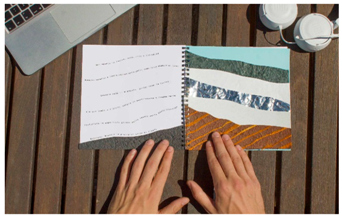

The approximately 50 resulting products (some of them are represented in

Figure 4 and in a more specific description in

Appendix A) are conceived upon a survey of the distinguishing features of the ecomuseum, far from the traditional merchandising stereotypes, seeking product innovation in the name of functionality, sustainability, formal language, active involvement of the user, and affordability.

3.3. Classification and Analysis of New Merchandise Proposals

The set of design proposals collected has thus been reorganized by the faculty into

Table 1 (and a short selection of them is also described and documented more in depth in

Appendix A), for an original comparison taking into consideration elements related to the museum, the territory, the public, the fields of uses and the design approaches.

Concerning the museum, the categories involved the two possible visit paths: (i) ScopriMiniera and (ii) ScopriAlpi. Of the total number of projects, 30 proposals were designed for the narration of the ScopriMiniera path, and 17 for the ScopriAlpi path. Even if this ratio apparently reveals a preference for ScopriMiniera path in terms of the topic of the visit, the corpus of proposals cannot be considered as divergent. In fact, a large number of references are rather in common between the two paths that belong to the same museum.

Concerning the territory, the geographical “radius of action” of the cultural reference pointed out in the proposal was taken into consideration. The possible categories for territory are (i) the mine; (ii) the Germanasca valley and (iii) the entire Alpine chain. A significant number of projects, 25 proposals, involve the mine as the cultural reference territory. Specifically, they deal with three main topics: the mineral, its extraction process and the life of the miner-farmer. Another 9 projects explore the cultural references from the Germanasca valley, investigating the culture of the Waldensians that historically lived in the valley (a pre-Protestant Christian movement founded by Peter Waldo in Lyon in the 12th century. The Waldensian movement today is centered on Piedmont in Northern Italy, but small communities can also be found in other parts of Italy, Europe and America), and the local flora. Finally, 14 projects involved the entire Alpine chain from the geological point of view, deepening the Alps formation process and its minerals.

Concerning the public, it was analysed as (i) children and students (ages 3 to 14); (ii) parents and adults (in particular on weekends and holidays); and (iii) mineralogy or mountain lovers, as these categories are coherent with the museum’s target visitors. In this case, since one project can be addressed also to more than one target, it is not possible to subdivide the proposals on just these three categories. Therefore, 12 proposals were addressed specifically to children and students—probably given the dominant target age group of the ecomuseum, represented by the groups of school students, and given the purpose of the ecomuseum itineraries itself—2 to mineralogy and mountain lovers, 17 to children and students but also to parents and adults, 4 to children and students but also to mineralogy and mountain lovers, 2 to parents and adults but also to mineralogy and mountain lovers, and finally 10 to every possible target.

Concerning the fields of use, the categories of (i) mineral packaging; (ii) consumer goods; (iii) stationery products; (iv) educational games; and (v) publications were considered. The most researched product type was consumer goods, with 14 design proposals; the areas of use were selected among different possible actions (e.g., bringing a packed lunch to the university environment/workplace, removing stains from clothes, lighting an area of the house, personal care); the second most investigated product type was educational games, with 12 design proposals, following a playful/educational will to transfer knowledge to the visitor through gameplay (for a state-of-the-art of serious games in the humanities and heritage field, as well as of the educational objectives of games in this domain see [

46]); the third most investigated product type in terms of project amount was stationery products, with 8 design proposals, typically present within the museum bookshop, and represented by some of the archetypes of merchandise items (postcards, little notebooks, note pads, etc.); then 9 design proposals were for mineral packaging, developed to satisfy the geology lovers and those curious about the rock and mineral world who often visit the ecomuseum; and finally 4 design proposals for publications were designed to narrate the topics of the ecomuseum itineraries to a transversal public, from youngest (pre-school) to oldest (adult). These categories were further deepened with sub-categories, which can be investigated in

Table 1.

Finally, concerning the design approach, the categories of (i) “reference to distinguishing features or details of the artefacts within different products” and (ii) “hint to the artefact” were considered, following Ugo La Pietra recurring design approaches [

41] (c.f.

Section 2.3.2). In this case, a significant number of projects, 32 proposals, adopted the “reference to details” design approach; instead, just 15 proposals opted for the “hint to the artefact” approach, commonly considered as a more intellectual and complex design approach.

In the next section, we will discuss the results of the above projects, and will demonstrate how the design operation is fundamental for creating evolved and top-quality merchandise for cultural heritage, as well as the successive and related positive outcome of the visit and cultural experience.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The “In miniera!” project will contribute to increase the

genius loci of the Germanasca valley and also to increase the value and the diversification of products offered to visitors. In the modern context,

genius loci became a typical expression adopted in architecture for identifying a phenomenological approach to the place making: the interaction between the place and its identity. With the expression

genius loci, people refer to the complex socio-cultural, architectonic, linguistic characteristics and habits that are typical of a place, an environment, a town. This is a cross-term, which incorporates both the characteristics of the place and those of the community living in that place. Furthermore, the project will increase the local economy (generated, first, by the selling of merchandise products [

47], but also coming from the productive activities carried out by local artisans), as well as the improved cultural consciousness of the visitors in relation to what they see throughout their tour. The items of merchandise have, in fact, been designed and will soon be manufactured with the purpose of being story-like, narrating their origins and capitalizing on their conveyable cultural content.

The languages used, and the possibility to modulate them as “figurative” or “metaphoric” [

41], enable products to be suitable for different Ecomuseum publics and to address the various aspects of the visit, through useful objects, objects of use, which are able to prolong the experience of the visit in other spaces.

In fact, the main workstream of the concepts developed was to extend the ecomuseum visit experience by transposing “mine actions” to daily life. The workstreams of the generated proposals are perfectly in line with the purposes and uses of the most evolved form of museum merchandising.

The merchandise design projects (a pool of about 50) have been recently assessed by the ecomuseum in terms of potential contribution to the communication of cultural content in the museum package. The feasibility of the first few ideas has been selected involving semi-handicraft entities of the Germanasca valley and the province of Turin. The museum and the Politecnico di Torino would like to favour a “zero mile” approach in terms of material, know-how, and technology supply. The aim of the “In miniera!” project is also to promote the territory (that can evolve even at an economic level, considering the craftsmen and other manufacturers of the merchandise). Moreover, the project can spread the growth of companies and artisans located in a specific geographical, territorial and cultural context, and represents the premise for developing yet newer local activities, and at the same time is a reference point for external contexts, near or far, in terms of duplicability of its approach and practices.

From the methodological point of view, it is worth highlighting the virtuous nature of the cooperation among different entities and cultural systems of the territory (the ecomuseum, the community, the design team at the Politecnico di Torino, the craftsmen and the small enterprises of the Germanasca valley) funnelled towards mutual promotion. Furthermore, the implications of this kind of project range from individual, to community to regional levels. From the individual point of view, projects comprising both didactic and research aspects offer the students-designers the opportunity to investigate new realities, deepening topics such as material culture, local community habits, and territory peculiarities, with the challenge of synthesizing those complex concepts into simple but understandable products, able to “communicate” to all. For the local community, these projects represent the opportunity to narrate and in some cases rediscover its own identity and culture. This action is necessary to keep alive the memory of a community. From the regional point of view, public administration can play the role of encouraging and sponsoring these kinds of activities and boosting the relationship with the territory, in order to improve the development and promotion of the territory itself. Moreover, the activities presented, focused within a local context, the Germanasca valley, can represent a best practice to be replicated in other regions or for other local communities in the same region, Piedmont.

With reference to the product’s commercialization, an important moment will be the definition of an agreement between the parts (Politecnico di Torino and Ecomuseum), in order to protect the intellectual property of students who developed the selected merchandising projects, and to allow their commercial exploitation by the Ecomuseum. This agreement, signed by students and the Ecomuseum, will be mediated by Politecnico di Torino and will regulate the project transfer through a lump sum payment to students (that will not imply the transfer of intellectual property, which will remain a prerogative of the student-designer). From the students’ perspective, as students are the real protagonists of this operation, this is an important step in increasing awareness of the importance of the design role for local cultural heritage organizations; they become design clients (in this case the Ecomuseum) of local design students. For these students, it is the first time that they can see and touch the results of their efforts, and also to be rewarded for them. It is a winning formula that we have already tested in other research and didactics operations that had as a result the creation of saleable products (i.e., the Materialmente merchandising collection).

Therefore, upon analysis of the operation from a critical perspective, the following short-term, mid-term and longer-term considerations may be weighed.

From a short-term perspective, it will be necessary to carefully control costs, the supply chain, and the price policies adopted for the new items of merchandise, created ad hoc by local handicraft entities: they shall thus express a strategy that is not marked by the maximisation of profit, but mostly by the promotion of the craftsmen. Moreover, it will be necessary to draft a precise customer feedback analysis based upon the satisfaction and sales of the new merchandise at the Ecomuseum, in order to fully understand the level of success among visitors and possible issues.

From a mid-term perspective, the activities to be performed may consider the collection to be “live” and complementable, using both the student design concepts and the development of new products upon analysis of the ecomuseum gift shop visitor feedback. Furthermore, the distribution of the merchandise may be expanded beyond the ecomuseum bookshop. In fact, these proposals start from the mine site and enlarge their geographical “radius of action” of cultural references up to the Alpine chain. Therefore, presenting them at commercial and recreation centres in the valley, in the province of Turin and in the nearby regions, may contribute to the creation of a widespread consciousness among the local communities about the local material culture.

Finally, regarding longer-term activities, the described research and education operation assigns to the university and its researchers the important responsibility of spreading and promoting the results and considerations involving territory-based (and not only) merchandise outlined in this article also to local, regional and national authorities, relevant stakeholders of the regional and national cultural system (Regione Piemonte—Piedmont region authority, and MiBACT—Italian Ministry of cultural heritage, cultural activities, and tourism). The aim is to act at a political level to dismantle definitively the practice of promoting Italian cultural heritage through common and cheap merchandise.

In conclusion, in terms of the repeatability of such an operation, the results obtained prove how—following an outlined, coded, and structured method—even students/pre-professionals or future designers still undergoing training are capable of developing concept designs that are coherent with the expectations of cultured, high-level museum merchandise.

In fact, the quality of the results obtained is not only sparked by the “fresh” perspective of a young generation of designers on the topic, or the strong potential of the cultural resources to be promoted, but by the method presented and tested throughout the operation. The implementation of such a method thus allows the repeatability of the project even in contexts and fields of operation different to that presented (e.g., art cities, environmental and natural heritage) by small groups of researchers and professional designers which may obtain interesting results in the scope of a coherent and conscious promotion of cultural heritage.