Abstract

This paper presents a qualitative study of Hurdal Ecovillage in Norway. It explores how the actors involved have interacted over time and contributed to shaping the ecovillage. The study demonstrates that the ecovillage as a concept is continuously refined both internally on an individual level and in the village, and in mainstream society. At stake is the question of ecovillage identity and what this should entail. The interviewed ecovillagers report two main motives for deciding to move to the village. One is to become part of the ecovillage community, while the other is grounded in the ecovillage as a means to achieve sustainability rather than as a goal in itself. Hurdal Ecovillage has undergone two distinct development phases. First, the members jointly owned the land, built their own houses, and attempted to be self-sufficient. The ecovillage was largely isolated from the local community. In the second phase, professional actors took over responsibility for developing the village, offering ready-made houses to be owned by individual families. This shift resulted in the ecovillage appearing more like conventional settlements. Today’s ecovillagers express a wish to constitute an attractive, sustainable alternative to conventional living, but to do so they have to maintain a distance between themselves and the wider community.

1. Introduction

The ecovillage (EV) movement has received considerable attention in the literature. For example, scholars have looked at how EVs, as a particular form of ‘intentional community’ and lifestyle movement, have emerged and evolved over the years, and at various barriers experienced in the process of establishing and maintaining such initiatives, which have often failed. Forster and Wilhelmus [1] (p. 378) for instance observe that 80 per cent of ecovillage communities have ceased to exist within two years of starting.

Typically, EV initiatives articulate an intention to change society by promoting and practising sustainable living. A substantial part of the academic work on EVs has focused on the shared values underpinning these initiatives, which constitute the essence of such projects for sustainable living. A central and overarching idea observed among EVs which is often articulated within the movement itself is the notion of ‘connectedness’ between, for example, human beings today and those of the future, or between humans and nature. Looking at how EVs are maintained and changing over time, Sargisson [2] (p. 398) points out that EV members are, on the one hand, often attuned to opening themselves spiritually and socially. On the other hand, to sustain their identity and purpose as a group, they need to maintain a social, ideological and normative distance to the surrounding society (‘estrangement’) (Ibid.).

Working from a sociotechnical transitions framework, Boyer [3,4] treats the relationship between niche initiatives such as EVs and mainstream society. The study of this relationship is key for understanding how the diffusion of niche practices occurs. Several studies have focused on understanding the process of translation by which niche practices influence or become adopted by mainstream society. Translation “involves changes in a dominant set of interdependent social, physical, or regulatory structures that accommodate the niche” [4] (p. 34).

Smith [5] argues that the success of niches at influencing the mainstream rests on the ability of the niche to form intermediate projects where the sociotechnical contexts between the niche and mainstream society might bridge. The conditions for such intermediacy are “when a niche shares some, but not all, properties of a regime it prefigures” [4] (p. 32). Other studies put forward the importance of the political and social contexts surrounding the lifestyle projects or the niches for them to develop successfully [6,7]. As Seyfang concludes: “Socio-technical transformations cannot be achieved by niches alone” [6] (p. 7632). Hence, the local context matters to the success of these niches, as does the initiator’s ability to network with other grassroot movements [8,9].

As an example of niche practices, this paper examines Hurdal Ecovillage in Norway with a particular focus on how the relationship between Hurdal EV and mainstream society was maintained and redefined over a period of 15 years. The objective is to contribute to understanding: (i) the significance of the local context in terms of defining the EV; and (ii) the tensions that may arise as the EV needs to maintain a unique identity and distance from the local context at a point in time where mainstream society is turning towards values of environmental sustainability.

We first explore how and to what extent residents of the EV express political and moral concerns when accounting for their choice and practising their lifestyle. We ask whether residents of Hurdal EV perceive themselves as being associated with a wider EV lifestyle movement, the intention of which is to produce social change. We follow Holland et al.’s [10] (p. 97) definition of a social movement’s collective identity as “participants’ shared sense of the movement as a collective actor—as a dynamic force for change—that they identify with and are inspired to support in their own actions”. Second, we focus on how the collective identity of the ecovillage in question changed over time. We acknowledge the possibility that there are multiple intentions, practices, and (partly shared) identities within the EV. Furthermore, following Sargisson’s [2] observation of the need for an EV to distance itself from the surrounding society, we are particularly interested in examining the relationship between the EV, the local community, and mainstream society, as it evolved over time, and which contributed to forming Hurdal EV’s identity (cf. the notion of ‘alter-versions’ treated by Holland et al. [10] (p. 106)). This perspective resonates with classical anthropological work [11] (p. 10) on group identity and belonging. To social groups, maintenance of boundaries (distance to other groups) is an enduring concern.

This study primarily reflects various groups’ perceptions of each other and does not seek to trace structural influences which the EV may potentially on mainstream society (which may be changing for different reasons). Thus, we do not provide a full account of the translation process which ultimately leads to diffusion. However, we show how the EV relates to mainstream society and argue that this micro-study of the dynamic relationship between an EV and its surroundings provides some insights into understanding translation processes in general. As we will show, a key feature in this process involves a certain level of tension in terms of ecovillagers’ need to handle and balance two contradictory concerns: their wish to influence mainstream society on the one hand, and maintaining their own, unique identity on the other. For these purposes, we examine various types of relationships that have contributed to the creation of Hurdal EV. This includes internal relationships in the EV, and the ecovillagers’ relationship with the local population in Hurdal and with mainstream society. We draw on in-depth interviews with residents, representatives of the local population, and with the developer/architect of the EV.

The next section presents a brief review of the literature on EVs and intentional communities. Section 3 accounts for the methods used in this study. In Section 4, we present Hurdal municipality and two key phases in the development of the EV. Section 5 presents the motivation of today’s ecovillagers for moving to Hurdal EV, and accounts for various types of relationships that have contributed to the creation of Hurdal EV. In Section 6, we discuss the findings, and Section 7 presents a conclusion.

2. Literature Review

Intentional communities are defined by Kozeny [12] (p. 18) as:

[…] a group of people who have chosen to live together with a common purpose, working cooperatively to create a lifestyle that reflects their shared core values. The people may live together on a piece of rural land, in a suburban home, or in an urban neighbourhood, and they share a single residence or live in a cluster of dwellings.

The current EV movement forms part of what has been described as the fourth wave of ‘intentional communities’ [13]. Smith [13] draws on Kanter [14], who identified the three earliest periods of intentional or communal development in the United States: the first wave was devoted to communities with a religious theme (continued up to 1845), the second emphasized economic and political issues (lasted up to 1930), and the third focused on psychosocial issues (peaked in the late 1960s). The current movement of intentional communities, including the growing number of EVs, is characterised by eclecticism and is “not as alienated from mainstream culture as were their predecessors; and they appear to be more adept at balancing individual and community needs” [13] (p. 111).

Globally, the increasing concern for climate change and the environment over the past decades has spurred renewed interest in intentional communities as potential models for sustainable living [15]. EVs tend to highlight four ‘pillars’ on which the movement is based: environment, economy, community, and consciousness [16]. Because EVs vary considerably in terms of which pillars are emphasized, Litfin uses the metaphor of ‘the windows of a house’ to highlight how different EVs embrace the four pillars to varying extents and in different ways [16] (p. 31). One example is the Findhorn Ecovillage in Scotland, which started as a spiritual community in the 1960s but which—since the 1980s and negotiations surrounding the Rio Summit—came to include environmental sustainability as a central pillar or ‘window’. Renewed interest in EVs should thus be understood in the context of increasing concerns about the environment. Kaspar [17] considers the EV movement as an attempt to create an integrated ethic in which both humans and nature are considered to have a value in their own right. Moreover, dissatisfaction with societal trends towards further segmentation of people and nature, development away from community principles, and withdrawal from political participation, appear to motivate the formation of EVs [17,18].

Current EV initiatives may also qualify as ‘lifestyle movements’ [3] (p. 2). By introducing this concept, Haenfler et al. [19] (p. 2) aim to bridge theories associated with social movements on the one hand, and lifestyles on the other. They seek to place the analytical focus on the “intersections of private action and movement participation, personal change and social change, and personal identity and collective identity”. Lifestyle movements (in line with political consumerism and socially conscious consumption) represent ways in which individuals express political and moral concerns outside explicitly political realms such as voting and protesting practices [20] (p. 452). Here, lifestyle choices constitute the protagonists’ main strategy to obtain social change, and personal identity work plays a key role [19] (p. 8). Lifestyle movements and scholarly literature pertaining to this subject are closely linked to studies of grassroot movements and niches which, in part, form sources of systemic change or societal transformation (see for instance, [5]).

Through their oft-articulated intention to change society by promoting and practising sustainable living, an important question is whether EV practices are diffused to mainstream society. Summarising works by different scholars [5,6,21,22], Boyer [3] points to three different pathways in which niche projects diffuse their practices to mainstream society:

- (a)

- Replication, meaning that practices (for instance the building of straw bale houses) spread through a network of dedicated activists, but are limited to that networks.

- (b)

- Scaling up beyond a network of activists—for instance diffusion of photovoltaics—and spreading to different groups in mainstream society.

- (c)

- Translation, where practices from the niches diffuse into mainstream society at a higher institutional level; for instance to municipal planning or building practices.

Smith [5] considers specifically the last point on translations between niches and mainstream society, analysing the interactions between them. He shows how niche diffusion requires sufficient common ground between the niche and the practices of mainstream society to impact the latter. Three different types of translation between the niche and the regime are identified: (1) How a societal problem guides the principles of the niche; for instance, how pressing issues of sustainability motivate the establishment of lifestyle movements and their guiding principles; (2) How interactions between the niche and mainstream society modify practices and strategies of the two; for instance, by adapting niche practices to lessons learnt about the mainstream; and (3) How pressing societal problems alter the context of the mainstream, bringing the latter closer to the conditions in the niche. Furthermore, Smith [5] (p. 440) proposes that niches that are too much in line with mainstream society will lead to little change, while radical niches too divergent from the mainstream will become detached and will only diffuse their practices to a limited extent. Hence, he concludes that translation most likely happens in intermediate projects where the sociotechnical contexts between the niche and mainstream society might be bridged. Niches such as lifestyle movements might need to compromise elements of their ideology in order to engage with mainstream actors and facilitate the translation from niche to mainstream [3].

Boyer [4] offers an account of the conditions that underlie diffusion pathways. It draws on in-depth studies with founders of cohousing initiatives in the US. While the cohousing movement articulates a socio-environmental critique and provides an alternative that mitigates some of the adverse effects of mainstream society, it also works in and with institutions in mainstream society [23]. Boyer [4] illustrates the importance of this pragmatic strategy in the translation process towards mainstream society. He also shows how the intermediacy of cohousing initiatives helps the translation process by its pragmatism. For instance, it does not demand that the residents abandon their economic independence or adhere to specific values or belief systems. The factors of success and the failure of grassroot initiatives like the lifestyle movements are investigated in the study by Seyfang [6]. She studies grassroot initiatives as strategic green niches with a potential for diffusion into mainstream society. Through studying community-based sustainable housing initiatives in the US, she points to the challenges of diffusing their ideas and practices beyond the niche. This is due to the fact that grassroot movements might need to invest a lot of effort into maintaining their community and ideas. However, she also points out that the translation processes of niche practices into mainstream society require certain political and social contexts in order to occur: “Socio-technical transformations cannot be achieved by niches alone” [6] (p. 7632). The factors for success and failure of niches are also investigated by Feola and Nunes [9]. They define success according to how niches manage to create social connectivity and empowerment, and contribute to improved environmental performance, also externally. The authors show that many of the members in these initiatives tend to focus on internal factors rather than external ones to secure their own development. The members also tend to pay little attention to material resources, which may be because of their heavy reliance on volunteers (also pointed out by [1,7]). Further, an initial incubation period seems to be an important explanatory factor for the success of these movements, as is a simultaneous interaction process between the niche and mainstream society, as also pointed out by Smith [5]. Feola and Nunes [9] emphasize that the local context matters for the success of the initiatives, and that geographical location and place attachment may also play a role. Urban grassroot initiatives are apparently less successful than their rural counterparts, which they suggest can be explained by a weaker local place attachment [9]. In line with this, but also expanding on the focus of Feola and Nunes [9], Nicolosi and Feola [8] studied a suburban grassroot initiative in the US. The local context played an important role in its success, but so did networking with other grassroot movements, cultivating an environment where they could perform experiments of social and environmental change.

Ergas [7] also studies the dynamic relationship between a grassroot initiative such as an EV and the mainstream society that surrounds it. She conducted a joint analysis of identity formation among ecovillagers on the one hand, and the macro-political structures on the other. The author showed that some of the studied ecovillagers (in the United States) projected a collective identity by attempting to be ‘a model of sustainable living’ for mainstream society [7] (p. 49). However, the ecovillagers had no unified vision of how to achieve this goal. Ergas [7] (p. 43) also found that the ecovillagers’ relationship with the dominant cultural structure is interactive. Here, mainstream society both provided opportunities for and posed constraints on sustainable living (e.g., local housing codes). In response, the ecovillagers sought to push back by modifying the limiting structures [7] (p. 50). This is an important type of relationship that will be examined in the present work.

Moreover, pointing to the importance of the political and social contexts for a successful translation of niche practices into mainstream society, North and Longhurst [24] argue that proximity to larger power structures may lead to more visibility and possibilities to transfer niche practices to other places. They thus challenge Feola and Nunes’ [9] conclusion that grassroot initiatives face more challenges in urban settings. North and Longhurst [24] argue that urban areas have a diversity of actors who are able to work on developing grassroot initiatives, and hence, add more robustness to the movement. Sager [25] elaborates these arguments by showing how intentional communities in urban areas may succeed in using activist planning to influence their position vis-à-vis municipalities, and in bringing their ideas to political decision-makers as a result of their proximity to these actors.

The potential mutual influence between conventional, mainstream architecture and traditional ecological architecture has been studied from the perspective of science and technology studies. Ecological architecture (often employed in EVs) aims at low-tech alternatives using local resources, and often demands active involvement from the inhabitants when building the houses [26]. Berker and Larssæther [27] refer to the architecture used in the first phase of the Hurdal project as “experimental building projects within and outside of the ecovillage movement” [27] (p. 103). As we will discuss later, the project consisted of low-tech, self-built houses using local materials, and confirmed the idea of traditional ecological architecture as home-spun and low-tech [26]. The majority of architects in Norway perceived this type of architecture as rather uninteresting and poorly designed [28]. Drawing on the work of Ryghaug [28,29], Sørensen [26] notes that, in the realm of architecture, it is the concept of sustainability associated with traditional ecological architecture that has been mainstreamed. This is in contrast with technologies like electric cars where the materials, practices, and processes are mainstreamed, and not the concept. However, as we will show, Hurdal EV went through different phases with radically different architectural designs; we will discuss how this affected the relationship between the EV and the local population.

3. Methods

We selected Hurdal EV as our case because it is the largest ecovillage in Norway. It also has an interesting historical trajectory, in that some of its characteristics as an ecovillage have changed over the years. As we elaborate below, the ecovillage shifted from a reliance on jointly owned, self-built houses and self-sufficiency to a pragmatic approach with ready-made houses and less emphasis on subsistence. By studying this shift and how interactions between various types of actors contributed to shaping the ecovillage, this case provides insights into how the ideas and concepts associated with an ecovillage are formed through a dynamic relationship with mainstream society. This relationship is important for understanding processes of translation.

Our main empirical material derives from interviews, as presented below. We also reviewed reports and visited previous studies and websites focusing on the Hurdal case. Two sources were particularly useful for understanding the history of the EV ([30,31]), and our account in Section 4.2 relies on a triangulation between information deriving from these sources and material collected during interviews. We also reviewed the general literature, previous studies, and online material. In the scoping phase, we searched scholarly databases for relevant literature using keywords such as ‘ecovillage’, ‘intentional communities’, ‘sustainable living’, ‘community’, and ‘Hurdal’. In the revision phase, we received useful input on additional references from two anonymous reviewers. We participated in the Hurdal Sustainable Valley Festival in 2015. The festival is an annual event organised by Hurdal municipality and attended by national politicians and well-known NGOs. During this event, we observed how the municipality representatives spoke about sustainability as a central element of Hurdal’s collective identity, and how they presented the EV as a central part of the municipality’s way of achieving sustainability. This event also gave us the opportunity to mingle informally with both participants in the EV and outsiders. To gain insight into the EV movement, we visited Findhorn Ecovillage, regarded as one of the first of its kind and often termed ‘the mother of all EVs’, in the UK in May 2016. We draw upon observations made by the research team on their frequent visits to Hurdal EV, as well as on reports and information retrieved online about Hurdal EV. The ecovillage also has two Facebook groups, one public and one private.

Hurdal EV has received substantial attention in the popular media. In 2015, the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation [32] produced a television documentary about Hurdal EV which claimed to document some of the challenges and conflicts experienced in the process of establishing the community. Our study also draws on the findings of this documentary.

3.1. Recruiting Respondents

In total, we conducted 23 in-depth interviews in 2016. Fifteen of these included individuals or families among the current 64 households (150 inhabitants) in the EV. Six interviews were held with people representing Hurdal’s local community (see below), and three were with individuals who played a central role in initiating and/or developing the EV: Kristin Seim Buflod (General Manager, Hurdal EV), Simen Torp (Filago) and Rolf Jacobsen (Aktivhus, formerly Gaia Architects). These three interviewees agreed to be identified by name in the present work. Seim Buflod is also one of the 15 ecovillagers interviewed.

With one exception, the ecovillagers were engaged in the current study through self-recruitment. One of the architects involved in developing the EV put us in contact with the communications adviser in Filago. Filago is a Norwegian company that develops and builds EVs. The communication adviser wrote an email to all the EV inhabitants describing the project and inviting them to participate in interviews. Fourteen households responded and were interviewed. In addition, we recruited one couple spontaneously while visiting the EV. All the interviews with the ecovillagers took place in their homes, and lasted approximately one and a half hours.

Respondents not affiliated with Hurdal EV were contacted directly by looking up their names online, calling them, and following up with emails. They included the mayor, the head of planning and building services in the Hurdal municipality, and four municipal employees (working at the primary school and in the commercial services sector). In addition to the 23 formal interviews, we talked to other individuals and groups we met in the Hurdal town centre and at the café in Fremtidssmia, the recently opened (2016) cultural centre run by the EV. These informal meetings provided additional insights into the relationships and interactions between EV inhabitants and the local population in Hurdal.

3.2. Interview Topics and Strategy for Analysing the Material

The interviews were semi-structured, which allowed the respondents to bring up issues of concern. We developed a specific interview guide for each of the three types of respondents (Hurdal EV, municipal staff, and people from the local community). Generally, after introducing ourselves and the project, we provided information about how the data would be collected, stored and used, and asked for consent to record the interviews. All participants received information about the project, including their right to withdraw, and how we would manage anonymity.

The interviews with the ecovillagers covered four main topics. First, we asked about their background (age, gender, family background, occupation, where they came from), their consumption practices in general, and their reasons for moving to Hurdal EV. Second, we asked them to elaborate on their experiences of living in the EV (the house, the solar panel and other equipment, social aspects, organisation of daily life, etc.) and whether their habits, consumption patterns and attitudes had changed after moving to the EV. Third, we invited them to reflect on their relationships with fellow inhabitants in the EV and with the local community. Finally, we asked about their views on broader issues such as the role of EVs in mainstream society.

The interviews with the local population centred on their views on the process of establishing the EV and on the relationship between the local administration/population and the EV. In the interviews with the EV developers, we focused on the process and the various individuals, technologies, and relationships involved.

Four researchers conducted the interviews, most of them individually. With three exceptions, the interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. To help structure the analysis, we produced a coding tree with key issues from the interview guide, and systemised and coded the material accordingly.

4. Hurdal and the Ecovillage: The Place and the Project

4.1. Hurdal

Hurdal municipality is situated in Akershus County, about 80 km from Oslo, and comprises 2910 inhabitants (2016). Hurdal EV is situated approximately four kilometres from the administrative centre. Figure 1 shows where Hurdal and the EV are located.

Figure 1.

Map of Hurdal municipality and the ecovillage.

The municipality’s stated ambition is “to be a plus society by 2025, which implies that Hurdal will be carbon neutral or better, experience economic growth, and provide improved quality of life to inhabitants and visitors” [33].

4.2. Establishing Hurdal Ecovillage

4.2.1. Phase 1 (1996–2009)

The story of Hurdal EV goes back to 1996 and the establishment of the ecocommunity Kilden Økosamfunn [30]. The founders of Kilden wanted to establish an EV in Norway. This group looked at approximately 60 different properties in the region around Oslo to find a suitable plot, and in 2001 came across the property in Hurdal, which was for sale. At the same time, the community was approached by the mayor of Hurdal, who was positive about selling Gjøding farm, owned by Hurdal municipality, to the EV group. Gjøding was situated only an hour’s drive from Oslo, had a substantial amount of land for growing crops and attractive plots for building houses, and the municipal plan had already allowed for the building of houses in this area. In total, Gjøding covers 146 acres of land, of which 40 acres is farmed land. The ecocommunity proceeded to establish an EV on this site. The community rented Gjøding from 2002, and members of the EV built temporary housing using materials such as straw and wood, in line with traditional ecological architecture (see Figure 2) Euro pallets were used for the foundations for some of the houses because they were built on agricultural land. The municipality therefore had to grant dispensation from the Planning and Building Act on the condition that the houses would be removed after three years. However, the process of establishing the village took longer than expected (actually 10 years), and permission to keep the houses was extended several times.

Figure 2.

Self-built houses in Hurdal EV, Phase 1. (Photo: Simen Torp).

An EV cooperative was established in which each member owned a share of the farm and had a say in the decision-making process [30]. The initial inhabitants had to carry the costs of establishing the EV, and subsequent newcomers to the village had to pay a certain amount to join.

In 2001, the cooperative began collaborating with Gaia Architects, an umbrella organisation for architectural firms interested in contributing to sustainable design [34]. The Gaia project, headed by architect Rolf Jacobsen, assisted the cooperative in developing the zoning plan for the area as part of the approval process for building the houses.

However, the project soon faced challenges in the county administration [31], due to a conflict over the protection of important cultural heritage sites. Spruce trees on the hill that formed part of the site planned for the EV were a central element of the cultural heritage site. However, just weeks after the cooperative’s application was rejected by the county administration, a fierce storm hit Hurdal. As a result, all the trees were blown down, and the county subsequently issued approval for the plans. In 2004, the EV bought Gjøding from the municipality, and in 2006 the zoning plan was approved.

The small EV community lacked the necessary economic and legal expertise. For instance, obtaining funding to establish a substantial number of new houses proved a major challenge. They therefore decided to collaborate with a developer who would carry the financial risk. They also saw a need for a different concept for building the houses. Self-building required a lot from individuals in terms of expertise and time [27]. Hence, the EV project turned towards using ready-made modules and individual ownership of properties and houses.

4.2.2. Phase 2 (2009–Today)

The overall zoning plan for the EV was approved in 2009. The company Aktivhus was established the same year, partly as a result of the experiences gained by Gaia Architects in Hurdal, where they saw a need for standardised houses that could be produced more professionally than those made in the first phase of the EV development. Gaia also saw a potential for promoting eco-friendly houses more generally, and was motivated to offer an alternative to passive houses [27], which were mainly designed to minimise building energy consumption and take broader environmental aspects, such as the life cycle of materials, into account.

Aktivhus provides module-based, eco-friendly houses under a concept referred to as ‘Shelter’ [35] and became a close partner and important actor in Phase 2 of the EV.

The financial challenge remained. In its search for a developer, the EV tried to establish collaboration with several actors. In 2012, the company Vitrina AS (later Filago) took over financial responsibility for the project. Some of our respondents said they felt very relieved when an investor was willing to take over the debt.

Construction of the Shelter houses started in 2013 (see Figure 3). Aktivhus had to balance the ideals of ecological architecture (e.g., natural materials, natural ventilation, healthy indoor climate and energy-efficient construction) with national regulations and available support schemes. For example, to meet the energy requirements specified in the Regulations on Technical Requirements for Building Works, pursuant to the Planning and Building Act (TEK 10) and zero emission requirements, which would entitle the group to considerable support from Enova, they installed solar panels on the roofs. (Enova is owned by the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy, and was established in 2001 to contribute to reducing greenhouse gas emissions and transitioning to climate-friendly energy consumption and sustainable energy production). Furthermore, in order to better regulate ventilation and indoor climate, some of the houses were equipped with smart technologies. To receive additional support, the project also agreed to install monitoring equipment in some of the buildings to enhance research. This led to the introduction of smart technologies for controlling window screens, lighting, etc. Nonetheless, the architect was determined to use natural rather than balanced ventilation, hence active rather than passive houses.

Figure 3.

The Shelter houses in Hurdal EV. (Photo: Nadia Fransen).

However, the EV faced new challenges when subcontractors went bankrupt and technical equipment failed to function as prescribed. As a result, Aktivhus nearly went bankrupt. As shown below (Section 5.2), there is still considerable frustration among our respondents over the equipment, as well as concerns about the financial viability of the two companies involved. Table A1 in the appendix summarises the two main phases, some of the characteristics of the EV at the two points in time, and how the EV is regarded by the municipality and the local community, though our material on the latter group is limited.

5. Identities and Relationships

This section begins by presenting ecovillagers’ expressed motivation for moving to the EV. This will help us answer the question of whether ecovillagers perceive themselves as part of a lifestyle movement. We then examine how ecovillagers relate to each other and to other internal ‘actors’ such as houses and smart technology, and how they relate to the local community. We discuss the implications of the findings in Section 6.

5.1. Stating Intentions: Why Move to Hurdal Ecovillage?

Our EV respondents varied in terms of when and why they moved to the ecovillage. Some of them had been there almost from the start while others had moved there recently. All expressed a wish to achieve a sustainable lifestyle. Two main types of motivation were mentioned, which we term ‘community’ and ‘example’. Though several respondents reported both types of motivation, most of them emphasized one in particular.

The first category, ‘community’, denotes respondents who said they were primarily motivated by the opportunity to join a community, both to meet other people with shared values, and to get away from conventional society where they found that their attitudes, views, and practices were at odds with or diverged from what was considered ‘normal’. The other category, ‘example’, denotes respondents who used the word ‘example’ to convey that their motivation for moving to the EV was to demonstrate to others what sustainable living may imply, and to inspire others to do likewise. As we elaborate below, the first type of motivation is directed inwards, while the second draws attention to the role of the EV and mainstream society.

5.1.1. Seeking a Sense of Community

The importance of social belonging was a theme in many of the respondents’ accounts. One male respondent (PH1) told us: ‘For sure, the dream is to have an environment that one recognizes and feels at ease with.’ A female respondent (PH2) provided more details:

There are people here who don’t think you are strange because you make such choices. Because you buy used clothes or don’t buy clothes. There is a complete understanding from people who live here. And it helps feeling that people understand you. I have received strange looks and things like that [outside the EV].

Other community-oriented respondents complained about the barriers to sustainable living in mainstream society:

We are environmentally conscious and think it may be difficult to have an environmentally friendly lifestyle in our society. In that respect, it’s no coincidence that we’re here.(PH9)

These quotes signal that the respondents had felt uncomfortable or constrained when living in conventional communities, which is why they wanted to move to the EV. People in this group elaborated on different aspects of the community dimension and on what living here meant to them. Some were preoccupied with giving their children a good upbringing in what they termed the ‘protective environment’ provided by the EV. Others, as PH2 above, said that they found it valuable to meet people who shared the same views as themselves when it came to consumption patterns and other issues. A passion for growing their own food was another highly motivating factor for moving to the EV.

On the issue of spirituality, six of our respondents specifically mentioned that it was important to them that the EV did not place too much emphasis on spirituality. At the same time, some ecovillagers said they appreciated the possibility to practice spirituality without being judged by others in the EV community.

5.1.2. Setting an Example

Some people said that their main motivation for moving to the EV was to “set an example” and actively seek to be pioneers who showed the way for others. They stressed the importance (six out of seven ‘examples’) of being part of a lifestyle movement that contributed to social change with respect to food consumption, transport, housing, and how people live together. For that purpose, they reflected on how their own activities match the ‘normal’ criteria set by mainstream society:

So we thought, okay, we want to try to live a bit more sustainably, or like push and see how far we can go, but at the same time, like, that it’s within the four walls of society and within normal boundaries. The good thing about being part of this project is that it’s, like, pretty … easily accessible in that respect. To the general public, too.(PH14)

Hence, in terms of setting an example, the link to society was important and should be actively maintained, as PH14 further elaborated:

Then there was, at least one of the most important questions to me, was … to get an impression of whether this was some sort of isolated unit, a little village on its own that took a step away from society to do something different, or if they actually were part of wider society and tried to take part in creating something.(PH14)

5.2. The Developers: The Architect Aktivhus and Contractor Filago

Respondents expressed mixed feelings about the architect and contractor. On the one hand, they expressed admiration for the houses and the contractors: “Innovation takes time, innovation is frustrating” (PH6). They appreciated the physical structure and quality of the housing. Few of them spoke about aesthetics, but many conveyed satisfaction with living in houses built from materials they considered to have a limited environmental impact. Several emphasized the good indoor quality and the direct access to outdoor air through valves rather than having a closed system of balanced ventilation. One respondent with a background in natural sciences said he highly appreciated the fact that the houses were not concealed “aluminium tins”, and referred negatively to passive houses. On the other hand, the respondents expressed dissatisfaction with several technical aspects of the houses (particularly in the early Phase 2), and the way in which their complaints were met by Filago, Aktivhus, and subcontractors. Respondents complained about draughts around uneven window frames, cracks in kitchen countertops and yellowing grout. Several also commented that the materials had been processed and shipped from eastern Europe and processed in Denmark—hence transported over considerable distances, with environmental implications.

A common question was: who would be financially responsible when technical problems occurred. Our respondent from Aktivhus underlined that his company was responsible for ensuring that the houses functioned. However, delays in getting things fixed and the lack of response to emails made many residents question this promise and Filago’s financial capacity to do the necessary work. Some respondents also doubted whether Filago “is as idealistic as they claim to be”. Others were uncertain of what property (the farm and the cultural centre) Filago actually owns today, or were sceptical about Filago’s previous involvement with a Czech company that went bankrupt after supplying building materials to the EV. Finally, there was considerable confusion among residents regarding the distribution of responsibilities between the ecovillagers and the three actors on the supply side: Aktivhus (the architect), Filago (the contractor), and various subcontracting firms. One of the points of confusion was that some individuals were said to be working for both Filago and Aktivhus. From the perspective of our respondent from Aktivhus, the shift from Phase 1 to Phase 2 represented a risk, in the sense that the people moving to the EV might lack commitment to engage in joint activities. For example, one year after Phase 2 began, there was uncertainty as to whether the new generation of ecovillagers would be interested in taking part in running the farm and/or establishing new joint initiatives.

The ecovillagers, on the other hand, argued that they did indeed possess the capacity to initiate activities. Most of the interviewed families belonged to at least one of many groups initiated by the ecovillagers (dancing courses, painting courses, wine club, Friday club for women, yoga courses, outdoor recreation, boating groups), and were by default part of the residents’ association (beboerforening), to which many contributed on a voluntary basis. Though there were some complaints about some individuals being ‘free riders’ rather than contributing to the common good, our interviewees were more concerned that Filago should relinquish some of its responsibilities.

I think many people, us included, expected that Filago and Aktivhus would not decide so much. After all, people have come here to discuss things thoroughly. So it kills our enthusiasm a little.(PH3)

Because people thought they could just start things here. I can shovel snow in the winter, so someone asked Filago if that was ok, and they said they’d already thought about that, so don’t bother. So then that person lost all motivation.(PH3)

Hence, there seems to be a mismatch between expectations regarding decision-making, with some residents calling for more independence while Aktivhus and Filago retain control to ensure the project’s viability. One woman put it this way: “People don’t want to follow [the developer’s] dream, but their own dream” (PH3).

5.3. The Local Community

The value of social involvement with the local community was often highlighted by the ecovillagers. Several expressed the importance of maintaining contact with mainstream society to avoid becoming isolated from it.

But I do hope there will be more … how can I put it … sort of integration. Between us and people in the village. I think it’s … well I think it’s important. That we don’t become some kind of sect.(PH9)

Moreover, it was the outward reach of the EV that had triggered some of the respondents to move to the EV (Section 5.1). Many ecovillagers regarded the Fremtidssmia cultural centre and the open courses (in dancing and painting) that were attended by people from Hurdal as a bridge between them and the local population (PH13). One man said he liked to exchange knowledge and gain traditional botanical knowledge in Hurdal (mapping meadow flora, PH14). However, another man remarked that some events were not so suited to the local population because they were too alternative or “very hippy-oriented”.

The respondents representing the Hurdal municipality spoke warmly of the EV’s influence on the local community, emphasizing the EV’s outreach and contributions to the Hurdal Sustainable Valley Festival and to activities involving the local school, where EV residents have taken part in teaching programmes: “Things move faster with their engagement” (HL2). They also expressed concern that not all EV families sent their children to the local school and stressed that Hurdal should be ‘a place in which people can dwell, live and work’ referring to the municipal strategy 2010.

Like the municipality employees, ordinary residents in Hurdal also acknowledged what they considered to be positive contributions of the EV. They pointed to the attention Hurdal had received nationally as a result of the EV, making Hurdal more visible:

How clever they’ve been in receiving all kinds of people, and that has opened, I mean, it’s put Hurdal clearly on the map right from the start, so there have been people from all over the world, and they’ve been here and worked for free.(HL4)

However, local satisfaction with the EV for it putting Hurdal on the map did not erase former, local markers of identity. The notion of Huddøling (meaning a native of Hurdal) came up in interviews with local residents. They emphasized that in order to be a Huddøling, one had to be born there, and hence, it would be hard for anyone moving to the village to acquire this label. Despite 30 or even 50 years of living in Hurdal, an Oslo-born resident may still experience being excluded from certain social networks: “You are and remain an immigrant, in a way” (HL1).

The local respondents gave vivid accounts of the transition from Phase 1 to Phase 2, and of their perceptions of the radical change that occurred in the kind of people that came to live in the EV over the years.

But all the first houses they built down on the farm courtyard, they were those straw houses covered with concrete on the outside, and that’s eco … eco … well, the beginning, in a way. And then … then we saw it for years … that those who were living there, it was all foot-shaped shoes and lilac scarves and thinking how living in the countryside was all lovely and cosy, everything had to be cultivated and … they nearly froze to death in the winter.(HL3)

Other comments about the first phase of the development of the EV included questions about the ecovillagers’ financial capability: “You can’t make a living from eating apples and carrots” (HL3); and about their lack of hygiene and tidiness: “The children were dirty and had problems at school” (HL1). However, local inhabitants also acknowledged the increase in economic activity that the EV had brought to the area and regarded this as a shift in relations towards greater ‘reciprocity’ (HL4).

Some local inhabitants also reported how some ecovillagers caused feelings of inferiority within the local community: “They’re posher than us” (HL1). Strengthening this impression of a hierarchy, local residents highlighted that the EV residents now had proper jobs and were living in “nice houses worth three million kroner upwards, more than other houses in Hurdal”.

6. Discussion

6.1. Positioning Hurdal EV in the Global Ecovillage Community

The concept of Hurdal EV, despite its young age, changed radically as the initiative moved from infancy (Phase 1) to early adulthood (Phase 2). Our empirical material was collected during Phase 2, but secondary sources [31] and accounts of the shift indicate that the first project largely resembled the four-pillar concept observed in other EVs across the globe [16]. In the current phase (Phase 2), the shared values of the actors involved appear to be less settled and less comprehensive, and most of the newcomers display a diversity of perspectives on and motives for joining the EV. However, both the developer and most of the ecovillagers tend to place a strong emphasis on environment (pillar) and community (pillar) as joint values in Hurdal EV. In doing so, they create and reproduce some key connections while living in the EV, both to the environment and to each other as a community.

As for the third pillar often associated with EVs, namely, economy, this aspect has less explicit connotations in Hurdal EV today than what has been observed elsewhere, where “the purpose of the economy is to promote human wellbeing within the limits of finite ecosystems” [16] (p. 78). Primary production (e.g., of food) constitutes an important economic element, as does sustainable consumption. However, in Hurdal EV, food production was not (at the time of data collection) a joint enterprise, but rather, was maintained either by the developer (Filago owns the farm) or by some individuals. In 2016 a preliminary community-supported agricultural scheme (CSA) was introduced to test whether this model would be suitable for organising the production of vegetables on the farm. With 30 members in 2016, the farm management and the CSA members embraced the model, and in 2017 all vegetables were grown by the CSA, which today consists of 116 members, mainly ecovillagers (personal communication, General Manager, Hurdal Ecovillage, 21 September 2017). Moreover, the system of individual ownership of houses has meant that the collective economy component of sustainable living in Hurdal EV is far less articulated than in many other EVs.

Regarding the fourth pillar of EVs, spirituality or consciousness [16], the present Hurdal EV declares itself publicly as a secular community. Although several interviewees explained that they were regularly involved in spiritual activities such as yoga and meditation, they all refuted suggestions by external individuals (such as the researchers) that spirituality was a central, shared dimension of their community. In official documents [36], Norway is characterised as a pluralist society (det livssynsåpne samfunnet) where many religions and practices coexist. Religious activities in Norway are considered to belong to the private sphere, and are less organised than before [37]. By regarding spiritual activities as private matters, Hurdal EV has adopted a stance on spirituality similar to that of mainstream society. In conclusion, Aktivhus, Filago, and the ecovillagers in Hurdal EV all strongly articulate the dimensions of environment and community, which become their markers of distance to the mainstream society, while the other two pillars (economy and consciousness) constitute more individualised spheres of practices, and represent less prominent parts of the community.

Moving from Phase 1 to Phase 2 implied adopting a more pragmatic approach to the values and principles guiding the EV. As Boyer [3,4] and Smith [5] point out, intermediate niche projects that lie between radical movements withdrawn from mainstream society and ones that are too much in line with it, are those with the highest chance of success. The pragmatic approach guiding the second phase of the development of Hurdal EV might be a successful recipe for translating EV practices to mainstream society (cf. [4]).

6.2. Translating Niche Practices to Mainstream Society: Pragmatism as the Way Forward

The presented material provides an account of how a Norwegian EV was created and recreated. We started off with the premise that there might be multiple discourses, practices, and identities within the EV, and that the ecovillagers’ collective identity might also be influenced by the perceptions and activities of outsiders, such as the local population in the Hurdal Valley, who provide ‘alternate versions’ [10] of what the EV is. After scrutinising the various types of relationships involved in this process, we are now in a position to discuss how social boundaries and identities played out in the process of creating the EV. Because Hurdal EV has gone through two radically different phases, its story is particularly revealing in terms of illustrating how the concept of an EV may change. The case of Hurdal EV demonstrates the relational nature of the ecovillage as a project and locus for identity construction, heavily informed through interaction with the outside world. The outside world has notably changed during this period.

The most striking shift in relations has been the way in which the local population perceives the EV, shifting from hostility to admiration. In the first phase, the relationship was highly distanced, and perceptions of ‘dirty children’ evoke associations with impurity and social danger [38]. By contrast, today’s local population expresses admiration for and sympathy with the EV, and in some cases, even a sense of inferiority vis-à-vis the ecovillagers. The most decisive moment in this transformation was when the project abandoned the experimental architecture resembling traditional ecological architecture and replaced it with ready-made housing. This shift in the choice of ‘cultural artefacts’ [10], or material representations of the EV, significantly changed local perceptions of the EV, and also how ecovillagers perceived themselves. This illustrates how modifications to niche practices may influence perceptions of the EV in mainstream society, and thereby, potentially increase the likelihood of EV practices translating and diffusing into mainstream society (cf. the second type of translation of practices between niches and mainstream society outlined by [4,5]). In this process of ‘moving closer together’, the EV nonetheless needs to maintain a certain level of distance from mainstream society in order to sustain its identity. In this connection, we found some variation in opinion amongst the ecovillagers in terms of how they wished to relate to the outside world.

All ecovillagers shared the basic value of environmental sustainability and wished to become socially engaged in a larger group of like-minded people. However, when we probed further into their motivation for moving to the EV, two main types of rationale appeared in people’s arguments and reflections: community orientation, and setting an example. These two categories are not always mutually exclusive, and to some they may constitute conflicting concerns. Interestingly, in both cases, mainstream society serves as the reference point, albeit in different ways. The community-oriented rationale implied moving to Hurdal EV in order to get away from the criticism in their former neighbourhoods. For example, they wanted to be able to keep chickens or grow carrots without being judged by others. By moving to the EV, community-oriented individuals created distance between themselves and mainstream society. They became typical inhabitants among equals rather than outcasts.

The other type of rationale implied a wish to set an example for sustainable living. This goal fits explicitly with perceptions of EVs as a lifestyle movement that actively seeks to promote social change [19] (p. 2). Individuals who emphasized this rationale cherish continuity with their former external relationships and networks, and seek to influence mainstream society. They underlined that the EV was not a sect, that the houses were very comfortable to live in, and that they were fortunate to be close to Oslo so that people could visit. Hence, their external networks, including the local population in Hurdal, are important witnesses to their self-creation: progressive, responsible people who have managed to merge their sustainability ideals with comfortable living. To distance themselves (and the EV) from being judged as too alternative, they spoke critically about practices associated with the EV in Phase 1, such as straw-bale houses, sects, and spiritual practices. Protagonists of the ‘example’ rationale expressed the need to display a collective identity that was normal enough for mainstream society to be willing to adopt their lifestyle. At the same time, as pioneers or early adopters in a sustainability market, they are likely to enjoy social esteem from their wider social networks [39]. Hence, the pragmatism inherent in the strategy of setting an example for sustainable living moved Hurdal EV towards being an intermediate project, i.e., what Boyer [4] identifies as a success factor for translating practices between niches and the mainstream. The two main types of motivation are guided by perceptions of the environmental problems inherent in mainstream society, and in both cases, these represent the core principles for establishing the EV [5].

Seemingly positioned at the steering wheel in the endeavour to create an EV according to their vision, we find Aktivhus (the architect) and Filago (the contractor). They expressed a clear intention to influence mainstream society and to be part of a lifestyle movement resembling our group of ‘examples’. The translation of sustainability practices from this niche to mainstream society is an expressed goal, and Hurdal EV is perceived as the start of a larger project in Norway. The enduring contact with the municipality in order to transform Hurdal into ‘Sustainable Valley’ in the long term confirms this ambition, and also confirms the arguments of Feola and Nunes [9] and Seyfang [6] on the importance of the local context. The interactions between the municipality and Hurdal EV have facilitated its development, both through the efforts made by the municipality to plan for the village, and through their mutual interest in promoting Hurdal as a Sustainable Valley.

However, the developers face a challenge in handling the internal diversity in aspirations. The most articulated tension between the developers and the ecovillagers was the issue of the farm in terms of who should own it and be responsible for operating it. While the developers seemed hesitant about surrendering control to the ecovillagers, the latter group called for more responsibility. Finally, the developers worry that the ongoing provision of ready-made houses in the open market will attract people to the EV who are not committed to sustainability. Hence, while wanting to be part of a lifestyle movement, the developers also expressed concern that the distance between the EV and mainstream society may dissolve. The risk involved in this balancing act was that of losing one’s EV identity. From this perspective, Hurdal EV has moved closer to mainstream society in terms of demonstrating how to live a sustainable life in a comfortable way. This corresponds with what has been termed the fourth wave of intentional communities, in which members increasingly attempt to become integrated with mainstream society rather than escape and become alienated from mainstream culture [7]. At the same time, the wider community has changed, becoming more attuned to the values and practices that constitute important principles for Hurdal EV. In Norway, sustainability is increasingly accepted as an important policy dimension, and concerns for climate change seem to be generating a growing number of initiatives for developing novel, more eco-friendly solutions [40]. This clearly illustrates how a pressing societal problem, sustainability, has altered the context by moving mainstream society closer to the niche, and hence, facilitating the translation of practices between them [5].

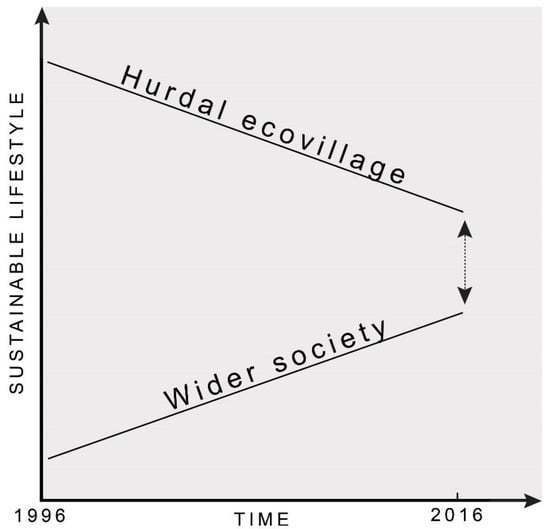

As mentioned above, Sørensen [26] suggests that the mainstreaming process in ecological architecture is more conceptual than innovative and practical, and that this field is still dominated by small-scale, locally-controlled activities using an experimental approach. However, the presented material on how Hurdal EV developed from the first to the second phase demonstrates that this mainstreaming process was not only conceptual, but also practical and technological. The EV adopted some norms held by mainstream society, and the interactions between the EV and mainstream society modified niche practices. Figure 4 below illustrates the translation process by which Hurdal EV and mainstream society have approached each other.

Figure 4.

The relationship between Hurdal EV and mainstream society.

In the early days of the movement, there was a large discrepancy between the ecovillagers’ values and lifestyle and those of mainstream society. As Smith [5] and Boyer [3,4] argue, the ability to translate practices from this niche to the mainstream might have been restricted because the lifestyle of the EV might have appeared too radical for mainstream society. Today, this gap has narrowed. Mainstream society has not necessarily become more sustainable. Although sustainable practices (such as driving electric vehicles) are increasingly being adopted, so too are unsustainable ones (such as air travel). But several sustainable practices, such as eating less meat, are now considered less radical than before. The EV concept has been modified to constitute a pragmatic and attractive sustainable alternative to mainstream society because it is not beyond reach, but rather, draws on a mix of values in terms of sustainability, comfort, and aesthetics that are widely shared. Some distance remains between the ecovillagers and mainstream society (illustrated by the gap in the figure in year 2016 (the year of data collection). Both internal and external forces are currently seeking to close that gap, but at the same time, it is crucial to ecovillagers to maintain a distance and an identity if the EV is to survive as an alternative to conventional living and also be able to push towards more sustainable lifestyles in mainstream society [4,5].

7. Concluding Remarks

In this paper we have examined how the actors involved in Hurdal EV have interacted over time and contributed to shaping the ecovillage. The study shows how the ecovillagers have sought to maintain a distance between themselves as a group and the wider community while balancing the various values and practical implications of living in accordance with such values. It demonstrates how the ecovillage as a concept is changing, both internally within the ecovillage community and vis-à-vis mainstream society. The different phases of developing Hurdal EV illustrate the importance of adopting an intermediate project [4,5] for translating practices from a niche—such as the EV project—to mainstream society. Adopting a pragmatic approach towards developing the EV, as was done in the second phase of Hurdal EV, is at least one element for success in this translation process.

The journey towards this more pragmatic strategy for developing Hurdal EV also involved modifying the pillars on which it was built. Only two of the four pillars of EVs [16] are clearly embraced by the Hurdal ecovillagers in the second phase of the development: community and eco-friendly living. The economy and consciousness pillars tend to be played down and kept more private. Most of the ecovillagers come to the EV to enjoy community life and share their interest in leading an eco-friendly lifestyle. Some of them openly emphasize a wish to contribute to a lifestyle movement where their practices and ideas lead to social change. Others have a more inward orientation. When living in their previous neighbourhoods, the ecovillagers we met had sometimes experienced disapproval of their lifestyle, but in the EV they did not encounter such social sanctions. Despite their somewhat different emphases, however, they are all participants in a lifestyle movement, promoting private action towards social change, and cultivating a meaningful identity [19].

The adoption of a more pragmatic strategy in the second phase of the project has narrowed the gap between the EV and mainstream society. In the beginning, the EV inhabitants were largely isolated from the local community and were looked upon as odd. However, by mainstreaming the EV concept and practices through revising ecological architecture and streamlining a top-down process for promoting, constructing and selling houses, and recruiting new ecovillagers, Hurdal EV earned more esteem and acceptance for their values and practices from mainstream society. Moreover, the increasing general acknowledgement of environmental problems contributed to normalising the EV. In this process, the ecovillage as a concept was modified by different stakeholders and outsiders who contributed to the negotiations about what the EV should be.

This study clearly confirms the argument put forward by Smith [5] and Boyer [3,4] that the success of translation hinges on intermediate, bridging projects. Correspondingly, we find that Hurdal EV’s pragmatic choices and adjustments to move closer to mainstream society facilitated a bridging between the EV as a niche and mainstream society. It also illustrates the perceived risks associated with the EV should it move too close to mainstream practices, as losing its identity would also mean losing its ability to promote an alternative to mainstream lifestyles. Where this line should be drawn is contextually dependent and therefore dynamic, and involves work that is both inwardly and outwardly directed. What would too mainstream a practice entail for its ability to foster social change?

Author Contributions

Each of the three authors, H.W., T.W. and M.A. contributed equally to designing the study; collecting the empirical material; interpreting and analysing the material; writing the paper and substantially revising the work. All three authors have approved the submitted version and all three authors agree to be personally accountable for the their contributions and for ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated, resolved, and documented in the literature.

Funding

This research derives from the project Power from the People led by CICERO and funded by the Norwegian Research Council, project No: 243947.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the interviewees for sharing their thoughts with us, Rolf Jacobsen, Kristin Seim Buflod and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions and Brigid McCauley for editing and proofreading. Thanks also to Eilif Ursin Reed for providing the graphical illustrations (maps and Figure 4).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The founding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, nor in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The two phases of Hurdal EV.

Table A1.

The two phases of Hurdal EV.

| First Phase (1996–2009) | Second Phase (2009–2017) | |

|---|---|---|

| Physical buildings | Self-construction, traditional ecological architecture. | Ready-made units, modern ecological architecture including advanced technology. |

| Community markers | Every member had a say in joint decisions. | Individual homes: individual decisions Farm: owned by Filago, lack of clarity regarding decision-making in the future. Shared social activities, some also open to people outside the EV. |

| Environmental values | Clearly expressed | Clearly expressed |

| Spirituality | ? | Not a shared value |

| Position of municipality vis-à-vis the EV | Took initiative to collaborate. | Highly engaged in collaboration. |

| Position of local population vis-à-vis the EV | Distanced | Admiration |

References

- Forster, P.; Wilhelmus, M. The role of individuals in community change within the Findhorn intentional community. Contemp. Justice Rev. 2005, 8, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargisson, L. Strange Places: Estrangement, Utopianism, and Intentional Communities. Utop. Stud. 2007, 18, 393–424. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer, R.H.W. Grassroots innovation for urban sustainability: Comparing the diffusion pathways of three ecovillage projects. Environ. Plan. A 2015, 47, 320–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, R.H.W. Intermediacy and the diffusion of grassroots innovations: The case of cohousing in the United States. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2018, 26, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. Translating sustainabilities between green niches and socio-technical regimes. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2007, 19, 427–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G. Community action for sustainable housing: Building a low-carbon future. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 7624–7633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergas, C. A Model of Sustainable Living: Collective Identity in an Urban Ecovillage. Organ. Environ. 2010, 23, 32–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolosi, E.; Feola, G. Transition in place: Dynamics, possibilities, and constraints. Geoforum 2016, 76, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feola, G.; Nunes, R. Success and failure of grassroots innovations for addressing climate change: The case of the Transition Movement. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 24, 232–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, D.; Fox, G.; Daro, V. Social movements and collective identity. Anthropol. Q. 2008, 81, 95–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, F. Introduction. In Ethnic Groups and Boundaries; Barth, F., Ed.; Waveland Press Inc.: Long Grove, IL, USA, 1969; pp. 9–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kozeny, G. Intentional communities: Lifestyles based on ideals. In Fellowship for Intentional Communities, Communities Directory: A Guide to Cooperative Living, 2nd ed.; Kozeny, G., Sandhill, L., Eds.; Fellowship for Intentional Community: Rutledge, MO, USA, 1995; pp. 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, W.L. Intentional communities 1990–2000: A portrait. Mich. Sociol. Rev. 2002, 16, 107–131. [Google Scholar]

- Kanter, R.M. Commitment and Community; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Litfin, K. From me to we to thee: Ecovillages and the transition to integral community. Soc. Sci. Dir. 2013, 2, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litfin, K. Ecovillages: Lessons for Sustainable Community; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kaspar, D.S. Redefining Community in the Ecovillage. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 2008, 15, 12–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby, A. Redefining social and environmental relations at the ecovillage at Ithaca: A case study. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haenfler, R.; Johnson, B.; Jones, E. Lifestyle Movements: Exploring the Intersection of Lifestyle and Social Movements. Soc. Mov. Stud. 2012, 11, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobernig, K.; Stagl, S. Growing a lifestyle movement? Exploring identity-work and lifestyle politics in urban food cultivation. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G.; Haxeltine, A. Growing grassroots innovations: Exploring the role of community-based initiatives in governing sustainable energy transitions. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2012, 30, 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornetzeder, M. Old technology and social innovations. Inside the Austrian success story on solar water heaters. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2001, 13, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargisson, L. Second-wave cohousing: A modern Utopia? Utop. Stud. 2012, 23, 28–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, P.; Longhurst, N. Grassroots localisation? The scalar potential of and limits of the ‘transition’ approach to climate change and resource constraint. Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 1423–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sager, T. Planning by intentional communities: An understudied form of activist planning. Plan. Theory 2017, 17, 1473095217723381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, K.H. From ‘alternative’ to ‘advanced’: Mainstreaming of sustainable technologies. Sci. Technol. Stud. 2015, 28, 10–27. [Google Scholar]

- Berker, T.; Larssæther, S. Two exemplar green developments in Norway. Tales of qualculation and non-qualculation. In Actor Networks of Planning. Exploring the Influence of Actor Network Theory; Rydin, Y., Tate, L., Eds.; Routledge: Abington-on-Thames, UK, 2016; pp. 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Ryghaug, M. Miljøarkitektur: Fra grav til vugge? In Mellom Klima og Komfort. Utfordringer for en Bærekraftig Energiutvikling; Aune, M., Sørensen, K.H., Eds.; Tapir Akademiske Forlag: Trondheim, Norway, 2007; pp. 217–232. [Google Scholar]

- Ryghaug, M. Towards a Sustainable Aesthetics: Architects Constructing Energy Efficient Buildings. Ph.D. Thesis, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Halvorsen, R. Kilden Økosamfunn. Samfunnsliv, 20 June 2003; 1. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, F.; Torp, S. 10 økolandsbyer på 10 år i Norge. Report Supported by the Norwegian Ministry of Climate and Environment, Oslo, Norge, 2003. Available online: http://okosamfunn.no/wp-content/uploads/10-okolandsbyer-paa-10-aar-i-Norge.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2017).

- NRK. Økolandsbyen. (A Documentary on Hurdal Ecovillage in Four Parts). Norwegian Public Broadcasting Corporation, 2015. Available online: https://tv.nrk.no/serie/oekolandsbyen (accessed on 20 September 2017).

- Bærekraftsdalen. Available online: http://www.sustainablevalley.no/ (accessed on 9 September 2018).

- Gaia Arkitekter. Available online: http://www.gaiaarkitekter.no/ (accessed on 6 February 2017).

- Om Aktivhus. Available online: https://www.aktiv-hus.no/page-om/ (accessed on 22 February 2017).

- NOU. Det Livssynsåpne Samfunn—En Helhetlig Tros- og Livssynspolitikk. NOU 2013:1, 2013. Available online: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/nou-203-1/id711212/ (accessed on 13 September 2017).

- Taule, L. Norge—Et sekulært samfunn? Samfunnsspeilet 2014, 1, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, M. In the Active Voice; Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd.: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Pantzar, M. Domestication of Everyday Life Technology: Dynamic Views on the Social Histories of Artifacts. Des. Issues 1997, 13, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Westskog, H.; Selvig, E.; Mygland, R.; Amundsen, H. Kortreist Kvalitet. Hva Betyr Omstilling Til et Lavutslippssamfunn for Kommunesektoren? KS FoU-Prosjekt nr. 154025; Norwegian Association of Local and Regional Authorities (Kommunenes Sentralforbund): Oslo, Norway, 2016. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).