Abstract

The Circular Economy has been posited as a solution to the rise of environmental decimation with growing global economic prosperity, by introducing new systems of production, consumption, and disposal. Current literature has explored circular economy business models, such as product service systems (PSSs), and has identified some issues that represent both behavioral barriers and motivating factors when it comes to consumer acceptance of these new models. However, there are few studies that incorporate a marketing and communications perspective on the circular economy or which focus on the ways in which businesses providing circular products or services currently use communications to market their offerings and influence consumer behavior. This paper represents an initial, exploratory study that identifies ten groups of concerns or ‘factors’ from the literature that affect consumer acceptance of circular value propositions. It then uses two models from the field of design (Dimensions of Behavior Change and Design with Intent) to interpret examples of web communications from four retailers of circular products and services, and to suggest future marketing and communications strategies for use in business and research. It finds that design frameworks can provide a relevant and comprehensive means to analyze marketing strategies and suggest less binary approaches than for instance green marketing.

1. Introduction

Human existence as we know it is increasingly under threat from the pressure placed on Earth’s systems by population growth and increasing activities related to production and consumption. Four of nine planetary boundaries have now been crossed as a result of such human activity, and climate change, loss of biosphere integrity, land-system change, and altered biogeochemical cycles are now putting in jeopardy the stability of global systems and the wellbeing of people in all parts of the world [1]. Businesses are under growing obligation to mitigate the effects of their externalities whilst maintaining the current model of economic growth, and are turning to concepts such as the circular economy to help them with decoupling environmental impacts from continued development [2]. An exact definition of circular economy still lacks consensus, but it is generally agreed that current business models, products and services must be redesigned so that ‘linear’ models ending in waste are replaced by those incorporating durability, re-use, repair, refurbishment, and recycling [2]. In the case of business models, one-off sales would be replaced by access or rental, often referred to as product service systems or PSS [3].

Until now, however, circular economy literature has mostly focused on service and business model changes, and has somewhat neglected the significant shift required from consumers to accept these changes [4]. Ever since Edward Bernays and the transformation of the United States from a ‘needs’ to a ‘wants’ society [5], consumption has been a dominant paradigm of the 20th and 21st centuries in which our norms, values, symbols and stories have normalized the exponential consumption of food, energy and materials [6]. But increasingly urgent calls are being made to mitigate excessive consumption, and radical approaches such as sufficiency are gaining traction [7]. For now, however, a consumption-based lifestyle remains entrenched, and circular economy models such as repair or rental need to be made attractive to consumers accustomed to fast acquisition and disposal [8].

Despite the prevalence of the consumption paradigm, the power of consumer—or user—behavior has until now perhaps been underestimated [9] and underrepresented in academic literature on circular economy research. Several factors that affect consumer acceptance of circular economy-type product offerings have been identified, however these are yet to be fully tested in ‘real-world’ scenarios. Much of the literature focuses on business and revenue model development, and implications for supply chains and product-service development, but how these circular companies seek to influence their customers’ behavior or influence the relationship they have with them through marketing and communications practices, remains mostly undiscussed. This is why we chose to explore a number of relevant frameworks for their relevance in understanding user behavior and preferences in the context of a circular economy.

The field of design for sustainable behavior (DfSB) was considered an obvious starting point as it has examined and developed models that describe the influence of product and service design on people’s behavior [10], especially in a sustainability context that is central for the circular economy. However, the role of communication strategies in the application of sustainable design and behavior change [11] has remained underexplored until now, which is why we chose marketing literature, and in particular green and social marketing, as a potentially complementary field. For the most part DfSB has previously addressed the subject of behavior change for individuals during the phase of use, and has developed a number of frameworks and tools in order to do this, whilst social and green marketing have attempted to influence the choices of consumers at the purchase phase for social or environmental benefit. In deciding how to market the new offerings of circular companies, it can be useful to bring together insights from these different fields to integrate information, concepts and tools in the interests of interdisciplinarity [12], and also to explore some current practices of companies that promote circular economy models.

In summary, this paper aims to explore the applicability of design frameworks in analyzing the marketing communication strategies of businesses that promote circular activities, with a focus on communication through their websites, and to assess the potential for improving the future design strategies of other circular companies. Specifically, it asks: what strategies for influencing consumer behavior towards more sustainable patterns are proposed in the design and marketing literature, and to what extent are these relevant and useful in analyzing the marketing communications of companies that promote circular consumption activities through their websites? By doing so, the aim is to present a novel contribution to the discussion on how industry can engage users better in their efforts towards developing circular value propositions.

2. Relevant Frameworks from Literature

2.1. Models of a Circular Economy

Several authors have pointed to a lack of research focus on the everyday role of the consumer in a circular economy, and also on the design and business models that can facilitate or hinder these [4,9,13]. Transition to a circular economy may require an increase in consumer involvement, for instance through the performance of activities such as product return or resale or the subscription to PSSs [3] that they were not previously involved in. But much of the circular economy literature to date fails to address the challenge of translating these new concepts into concrete action through engaging consumers in behavioral change.

Some studies have provided frameworks that attempt to lay out principles and practice for circular economy design and business models. Den Hollander et al. and Bakker et al. [14,15] reference Stahel’s principle of inertia and product integrity, asserting that, in the case of products, ‘prolonging and extending useful lifetime by preserving embedded economic value is the most effective way to preserve resources’ [14]. Whilst acknowledging that the product’s lifetime in use is often determined by its perceived value according to the consumer, they point to the necessity for business models and designs that allow for this preservation of economic value, and advocate a model of design for product integrity through long use (resisting obsolescence), extended use (postponing obsolescence) and recovery (reversing obsolescence) [14]. Bocken et al. [16] also provide a model for circular product design and business strategies that facilitate slowing or closing the loop through, for instance, extending product lifetimes, designing for disassembly, providing an access or performance model, or encouraging sufficiency.

Drawing on these studies, and work by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation [2], this paper selects four principles of a circular economy and uses four representative businesses to explore their marketing communications with customers via their websites:

- Longevity (i.e., encouraging long use, or resisting obsolescence)Example business: Tom Cridland (TC)

- Leasing (i.e., PSS or servitization, slowing the loop by providing access over ownership)Example business: Girl Meets Dress (GMD)

- Reuse (i.e., extended use, or postponing obsolescence through extending product life)Example business: Patagonia Worn Wear (WW)

- Recycling (i.e., recovery, or reversing obsolescence through extending material life)Example business: Elvis & Kresse (E & K)

When it comes to marketing circular or sustainable consumption, it is recognized that companies have a role to play, and that increasingly this is about changing consumer behavior at both purchase and use phases [17]. Close communications between a company and its user or consumer group are key to the success of innovative business models such as PSS [18] and possibly other circular economy models, and marketing communications can be particularly effective in the introductory phases of a product or service cycle [19].

2.2. Marketing

Marketing may be seen as both a reflection of and influence on human culture, through the active creation of markets by companies using the traditional marketing mix of price, place, promotion and product (the ‘4Ps’) [20,21] to stimulate attention, interest, desire and action. Marketing is the communication of one to many (as distinct from sales, which is one to one), and a market-oriented firm is one which prioritizes market intelligence and a strong customer focus [22]. Brands and advertising are central to the field of marketing, and brands represent powerful conduits of meaning [23] that contribute to customers’ concepts of self. Perception, reputation and image are the essence of a brand, and it has been shown that advertising that taps into emotive concerns is more successful than purely factual forms—especially where the brand’s image is of especial importance to the consumer (e.g., with clothing) [24]. Advertising is designed to both inform and persuade, and successful advertising can manipulate people’s desires and intentions in such a way as to create needs for goods with which they were previously unfamiliar or not interested in purchasing [24].

With the growth of the world wide web, a company’s marketing capacity and identity as perceived by its consumers is largely cultivated via its website, with factors such as visual appeal, ease of use, interactivity, trust and playfulness becoming essential in converting repeat customers online [25]. The challenges of competitor differentiation and lack of personal contact or influence over customer location are more difficult in online scenarios, and yet the internet has been defined as a powerful tool for retailers: search engines select required information, websites can be frequently updated and accessed from a number of devices in many locations and timezones, and Web 2.0 has enabled new levels of user interaction and collaboration [26].

2.2.1. Green Marketing

The theory and practice of green marketing has developed over more than 30 years, and the field provides valuable insight into the development of new markets for products and services with lower environmental impacts or higher sustainability credentials [27,28], in particular through companies’ communication with consumers. As with conventional marketing, green marketing strategies make use of segmentation, targeting, positioning and differentiation as well as the 4Ps marketing mix, with most consumers reporting positive attitudes to green advertising and promotion [27,28]. In practical terms, green marketing has evolved from reassuring customers with end-of-pipe solutions that mitigate pollution and address moral issues, to creating new markets and competitive advantage for business through desirable green products and services; more recently it has attempted the ‘normalization’ and integration of sustainability [29,30] by introducing longer term perspectives and addressing business models such as localization or product service systems [28]—which could also be seen as facilitating a circular economy [3].

Green marketing literature has applied theories from several other disciplines [27] to examine the success of different approaches to green consumption—for instance showing how framing messages differently affects consumers’ purchase attitudes and intentions [31,32], and that people’s perception of value is strongly dictated by how that value is communicated [33,34]. There is a tendency for green advertising to make rational appeals or expect that listing functional advantages will be enough to persuade consumers to buy the product, whereas research shows that emotional appeals, or those using both functional and emotional elements, actually carry more weight [33,35]. Moreover studies suggest that green marketers need to emphasize both tangible and intangible value (e.g., reduced costs as well as moral satisfaction), and align environmental benefits with consumer self-interest in order to increase sales and consumption [32,33]—as although those with higher environmental involvement can be influenced by environmental information, both those with higher and lower environmental concerns are likely to be affected by how the purchase will make them feel [33,35].

However, although green marketing supplies some useful frameworks for managers wishing to cultivate green customers, it has received criticism for taking an overly cognitive and behavioral approach that focuses on the psychology of the individual whilst tending to ignore social and cultural contexts [27,28]. Research studies can be contradictory or even inconclusive [33,34,35]. The rebound effect and values-action (or attitude-behavior) gap are well known phenomena that can scupper the benefits of efficiency savings through green consumption (rebound effect [28]), and show that consumers do not always follow up their green attitudes and intentions with sustainable consumption behaviors (values-action gap [33,34,35]). Environmental labelling has likewise not brought the hoped-for upturn in green consumption, and such tools have even been condemned for the plethora of programs, costs, and lack of consumer focus [20,36,37,38]. Greenwashing, which involves positive environmental communications but poor actual performance, is another accusation that has been levelled at the field of green marketing [28]. In general people are positive about supporting environmental issues but unwilling to change their lifestyles, and ‘green’ products may also be viewed as unpleasant, inconvenient or weird [39]—possibly because industry has previously focused on creating green products, rather than products that consumers actually want. More radical perspectives further denounce the very practice of marketing as an ‘active creation of wants’ and inimitable to sustainable development [20], as it ignores the wider question of consumption reduction [30].

2.2.2. Social Marketing

The concept of social marketing was born in the 1970s and has developed as an approach that utilizes conventions of traditional marketing and behavioral science, such as the 4Ps, norms, prompts and social diffusion, to bring about behavioral change for the benefit of a community or society (e.g., in the field of healthcare—to encourage the cessation of smoking) [30,40,41,42,43]. Unlike commercial marketers, which compete with other brands selling similar goods and services to consumers for purposes of financial gain, social marketers usually work on behalf of governments or non-profit organizations, competing with peoples’ current behaviors in order to sell them more beneficial behaviors for purposes of societal (and sometimes also commercial) gain and removing the barriers whilst simultaneously stimulating the motivators for action [42,44].

In terms of behavior change for sustainability, it has been argued that people rarely shift their conduct as a result of information provision, and that many green marketing approaches take an overly rational approach—neglecting consumers’ cultural and symbolic context and emotional responses [30,41]. Whereas green marketing tends to ignore the non-purchase elements of consumption (e.g., use and disposal) and focuses largely on products, social marketing takes a more customer-oriented or user focused perspective towards changing and maintaining new behaviors such as recycling [30], building relationships, and using emotion and humor as tools of communication.

However, accusations of social engineering have sometimes been targeted at the social marketing field [28], and its usual focus on curbing unhelpful behaviors (e.g., reducing smoking in the healthcare sector) has also proved difficult to reconcile with principles of sustainable consumption, which tend to implicitly accept the norms of growth and unlimited consumer choice [28]. But Peattie and Peattie argue that social marketing does in fact provide a suitable model for so-called ‘anti-consumption’, and in doing so suggest several modifications to the marketing mix which could also fit with PSS or a circular economy [30]. For instance, shifting from products to propositions, from place to accessibility (e.g., access over ownership), from price to costs of involvement (e.g., time and effort), and from promotion to social communication (e.g., relationship building instead of one-way promotion).

2.3. Design for Sustainable Behaviour

In recent years the growth of user-centered and service design has seen the field of design become more fundamentally concerned with a customer or user-centric approach. Design for Sustainability and in particular Design for Sustainable Behavior (DfSB) have emerged as areas of design research that explore how to influence the environmental impact of consumers’ activities, mostly during the use rather than purchase phase [45]. As with green marketing, DfSB focuses on individual behavior change and incorporates psychological, sociological and economic perspectives, drawing on the theory of interpersonal behavior, comprehensive action determination model (CADM) [46], theory of planned behavior [47] and PSS literature [10], and also uses Akrich and Jelsma’s work to describe how behaviors are ‘scripted’ into the design of our objects and surroundings [48]. According to such psychological approaches, new behaviors may be triggered as a result of extrinsic or intrinsic, hedonic or eudaimonic motivations and deliberate or automated decision making [49], and changes to consumer behavior will have the greatest impact when they address several motivating factors simultaneously [17,50].

However, although Design for Sustainability more broadly has addressed issues such as the repairability, disassembly and remanufacturability of products, DfSB literature has as yet paid scant attention to the behavioral challenges involved in transitioning consumers or users to a circular economy—focusing instead on efficiency strategies that encourage using ‘less’ [45]. Design is fundamentally concerned with creating change and making innovation ‘acceptable to users’ through interfaces and experiences [51], and is a means of configuring communicative resources as well as social interaction [52]. As has already been alluded to, conventional marketing techniques encourage consumers merely to switch brands, whereas a circular economy will likely require consumers to adopt new behaviors such as product return, rental, or reuse. DfSB, like social marketing, deals with behavioral change for sustainability, but unlike the more binary frameworks in conventional and green marketing (e.g., functional/emotional, self/other, high/low involvement etc.) several DfSB frameworks provide a more comprehensive set of dimensions. There are several tools and strategies in the DfSB literature that might lend themselves to an analysis of current approaches that businesses are taking in order to influence consumers in the adoption of certain circular economy behaviors—for instance through the design of their marketing and communications.

Two of these frameworks will be utilized in this paper, to assess their relevance in exploring and analyzing the marketing communications strategies used by such businesses on their customer-facing websites.

One is Daae and Boks’s 9 Dimensions of Behavior Change [53] (see Table 1), which describes different types of behavioral influencers. A key concept here are the strategies of control in any given activity, from ‘user in control’ to ‘product/system in control’ [53]. This continuum moves from informing, through persuading, to determining user actions. In terms of online communications it is suggested that some dimensions may be more relevant than others, for instance it may be difficult to exert absolute control over a user through a website alone, whereas it may be easier to convey meaning or empathy.

Table 1.

Taken from The 9 Dimensions of Behavior Change [53].

The other is Dan Lockton’s Design with Intent Toolkit [54], which again shows how design may influence behavior and provides 101 patterns in eight lenses. It is not focused on the circular economy or sustainability, but it provides a useful mapping tool for understanding challenges and possible solutions related to behavior change for sustainability. After an initial scan of the selected websites (see Method) a selection of patterns from seven lenses were identified by the authors as being most relevant to online marketing communications. For example, the architectural lens uses techniques to influence user behavior in architectural or urban planning scenarios, and the patterns here were less suited to 2-dimensional communications, so only one pattern (simplicity) was chosen. Conversely, the cognitive lens draws on heuristics, biases, and techniques from cognitive psychology to understand how users interact and make decisions and how designers can use this knowledge to influence their decisions, and most of the patterns for this lens were deemed relevant for the communications context. Likewise, patterns from the perceptual lens were deemed more relevant, as they use ideas from semantics, semiotics and psychology to discover how users perceive visual patterns and meanings, making them appropriate for analyzing online, visual design, and communications. The chosen patterns and lenses were adjusted during the analysis of the case study websites, with some initially chosen being dropped and others added to give a final total of 25 (see Table 2).

Table 2.

The 25 Design with Intent patterns that were identified as being relevant to digital marketing and communications.

2.4. Consumer Factors for a Circular Economy

Academic literature on the circular economy is still nascent, particularly when it comes to the consumer perspective. There are, however, a number of papers that deal with consumer reactions to activities that form part of a circular economy, such as reuse, remanufacturing, and PSS. In order to focus the current study on specific concerns that customers have in participating in these activities, an initial literature review of these papers was undertaken. Using ‘PSS’, ‘reuse’, ‘remanufacture’ and ‘consumer behavior’ as search terms, and a snowballing technique to find further studies, a series of papers was gathered that described and empirically tested motivating or barrier factors for consumer acceptance of these products and services. The most prevalent factors were found to recur throughout the literature, and these were identified and grouped into ten similar themes or factors (see Table 3). The grouping is based on the contextual understanding of how different authors approach the various themes. Different authors use different terminology to describe similar factors in different papers, and some might focus on motivators rather than barriers (or vice versa). For instance, Abbey et al. and Bardhi and Eckhardt refer to the barrier of ‘disgust’ (Bardhi and Eckhardt also speak of ‘contagion’) that people feel in using remanufactured or access-based products that have previously been touched by others, whilst Baxter et al. use the term ‘contamination’ to describe a similar attribute. Boks et al. call this same issue of previous usage a concern for ‘newness’, whilst for van Weelden et al. and Holmström et al. one of the problems of refurbishment is ‘lack of the thrill of newness’, and Mugge et al. echo this finding. Contamination and disgust are feelings evoked by a lack of newness, and thus all represent different facets of the same factor. Some authors deploy ‘convenience’ as a more general term, where others are more specific by explicitly pointing out availability as a crucial factor. Convenience and availability may be considered as an element of quality and performance, but we chose to distinguish the latter as a separate consumer factor because it bears more relation to the product or service in use, whilst convenience and availability denote ease in gaining initial access to the product or service. These ten factors formed a basis for investigations into four case study businesses’ online marketing communications with their customers.

Table 3.

A summary of consumer factors for a circular economy, taken from literature on product service systems (PSS), remanufacturing and reuse (awareness was also found to be a factor, but this is not included as customers will already be aware of the retailer by the time they are looking at their website).

3. Materials and Methods

This paper represents an initial exploration of marketing practice in a circular economy, in order to contribute to a growing body of work in this area. It uses existing frameworks from design and explores how they might be used to address factors that have been identified as affecting consumer behavior from the PSS, reuse, and circular economy literature. Which design strategies can be used to address which consumer factors, and can we find examples or case studies of this in practice? The analysis provides a basis for exploring the communication strategies of other circular businesses and identifying future opportunities. Circular economy approaches were identified (longevity, leasing, reuse and recycling, see Section 2.1), and companies that promoted each of these four were chosen using purposeful sampling for a multiple case study [7,69]. To improve generalizability and opportunities for cross-case comparison and analysis [70] the businesses were all selected from the fashion retail sector. Case studies usually include varied and extensive data sources [71], and the studies initially incorporated the businesses’ social media and offline marketing as well as websites, but for purposes of accessibility and to facilitate more detailed initial exploration it was decided to limit data collection to the websites alone.

Using subjective interpretive analysis in line with the exploratory nature of the paper, the Dimensions for Behavioral Change [53] and 25 of the Design with Intent patterns [54] were identified as relevant for interpreting online communications (see Section 2.3). The most relevant dimensions and patterns were identified and used as emergent theory [72] to interpret and analyze the findings.

Data collection involved gathering field notes [73] for each company and conducting within-case analysis [69] about the website’s general appearance and communications. The intent of the case studies was instrumental [69] and focused on understanding deductively how the communications strategies addressed each of the ten consumer factors identified in the literature through their digital communications discourses [74].

Rhetorical analysis was used to subjectively evaluate the different communication approaches and select examples from the four companies that accorded with the 10 consumer factors (see Table 3 and tables in Appendix A). Rhetorical analysis provides a critical, interpretive reading, may take into consideration pictures, videos or other media as well as written text and tries to understand how a message is crafted in order to gain a particular response [75]. The five ‘canons’ of rhetoric emphasize the importance of strategy, arrangement, style, resources, and delivery [75].

The tables in the Appendix A summarize for each company examples of how their digital marketing addresses the 10 consumer factors, and explains how these were qualitatively assessed and categorized according to the design dimensions or DwI patterns.

Communication design strategies were then extrapolated for each of the consumer factors (see Table 4), and the insights and applications discussed.

Table 4.

Suggestion of which communication strategies can address which consumer concerns in a circular economy.

4. Results

The following analysis is based on the tables in Appendix A, and develops this by cross-comparing and synthesizing the company examples according to the design frameworks, in order of the 10 consumer factors.

4.1. Contamination/Disgust/Newness

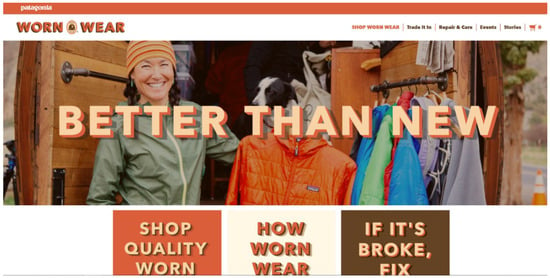

Tom Cridland (TC) (Figure 1) does not address this since all of the clothes are obviously ‘new’. For Girl Meets Dress (GMD) (Figure 2), dry cleaning is mentioned but otherwise the issue of newness or contamination (others having worn the dresses first) is notable by its absence, perhaps because GMD wants to reduce its importance or choice edit our responses. Both Worn Wear (WW) (Figure 3) and Elvis & Kresse (E & K) (Figure 4) tackle this concern by evoking meaning and eliciting our empathy. They use playful phrases such as ‘Better than New’ to rephrase and rename or frame old garments, encouraging customers to rethink their assumptions about used clothes and increasing their importance. Both companies anthropomorphize their products and give them personality with expressions like ‘scars tell the story’, ‘rescued’ or ‘heroic’ materials, ‘retired’ or ‘decommissioned’ fire hose that bring a new perspective to second hand items, engage our emotions, and lead us to see irregular or unwanted products as one-off, exclusive pieces.

Figure 1.

Tom Cridland website (accessed on 27 November 2017).

Figure 2.

Girl Meets Dress website (accessed on 27 November 2017).

Figure 3.

Patagonia Worn Wear website (accessed 27 November 2017).

Figure 4.

Elvis & Kresse website (accessed on 27 November 2017).

4.2. Convenience/Availability

All four retailers use the dimensions of encouragement and direction to address consumer concerns of convenience and availability. Promises such as ‘free shipping’, ‘returns and exchanges’ or ‘next day delivery’ may be familiar enticements, but ‘dry cleaning is on us’ or ‘trade in at a store near you’ are more unique to circular economy business models. As a model of PSS, which is more dependent on service quality, GMD in particular communicate the convenience of the service in many different ways; e.g., ‘rent a different dress for all your events’, ‘4000+ new season dresses’, ‘get a refund for anything you don’t wear’, ‘risk free’, ‘4 simple steps to rent the dress of your dreams’. Here the design patterns of simplicity, assuaging guilt and worry resolution (also evident in E & K’s ‘you don’t need to worry’) reassure consumers and motivate them to try the service.

4.3. Ownership

GMD also encourages customers to try their clothing PSS by tapping into familiar meanings of ownership and anchoring the rental service as almost the same as the ‘normal’ system they are used to: they can try lots of options and anything unworn will be refunded, ‘just like a normal shop’. The concern of ownership is not applicable to the other three businesses however, as they retain the traditional ownership model.

4.4. Cost/Financial Incentive/Value

As with convenience, the dimension of encouragement and the pattern of rewards are especially relevant to the consumer factor of cost. The longevity of TC’s clothing ‘will save you money in cost per wear’, with Patagonia Worn Wear ‘you get paid’ and can ‘see how much your (old) clothes are worth’, and with GMD the word ‘free’ is used frequently, often with bright pink letters for emphasis; e.g., ‘free stylist advice’, ‘first dress free’, ‘get this dress free’. GMD also uses first one free to hook customers. WW and E & K both employ the dimension of importance to highlight the value in ‘waste’ items, E & K through the high cost of products and ‘limited edition’ language (also indicating scarcity and framing), and WW by offering customers money in return for their old items.

4.5. Environmental Impact

GMD is the only retailer that has no indication or mention of environmental impacts. TC calls the company ‘the world’s number 1 sustainable fashion brand’ and a ‘campaign against planned obsolescence’, both obtrusive claims that nevertheless use meaning to get our attention, framing the brand as an environmental crusade. TC, WW and E & K all use emotional engagement to involve customers in the ethics of their brands: ‘keep the Worn Wear cycle in motion and avoid the landfills’ tries to enhance the importance of consumers’ behavior in contributing to the avoidance of landfill, to assuage guilt and to use direction to emphasize that this is the way the customer was already going. WW frames sustainability as responsibility and customer care, and uses reciprocation to encourage responsible consumer behavior: ‘one of the most responsible things we can do as a company is to make high-quality stuff that lasts for years and can be repaired, so you don’t have to buy more of it’. E & K are transparent and simple in communicating the recycled sources of their materials; e.g., coffee sacks, printing blankets, parachute silk—and use emotive language to enlist our empathy: ‘seemingly useless waste’, ‘rescue’, ‘lovingly hand weave’.

4.6. Brand Image/Design/Intangible Value

Meaning and storytelling are crucial to the image and values of all four brands. WW‘s ‘retro’ imagery, mood and color associations evoke the ‘make do and mend’ values of a previous age and the company’s emphasis on repair and reuse. Their partnership with iFixit also reinforces this values-based emphasis on repair. E & K’s ‘Story’ ties in the brand with the emotive subject of firefighters and rescue, engages our emotions and provokes empathy and highlights its purpose beyond profitmaking as the ultimate rescuer by saving materials from waste and donating profits to firefighters’ charities. Earthy colors (mood, color associations) evoke the fire and natural materials that are key to the brand, accreditations such as B-corp member and Brand of Tomorrow communicate its purpose-driven status, and values such as ‘sustainable luxury’, ‘ethical travel’ and the cycle of ‘rescue, transform, donate’ increase the importance of merely keeping waste materials out of landfill. GMD uses bright pink color associations and images of women having fun at parties to suggest a mood of excitement and engage our emotions, hoping to engage the customer in a direction they are already interested in, whilst ‘Join the Club’ suggests an element of exclusivity or scarcity. TC meanwhile seems to use bold statements and prominent contrasting colors obtrusively to gain our attention. Media endorsements and PR are also very important for this brand: Tom Cridland’s personality, celebrity friends, rock band, PR company and upper-class ‘From London to Hollywood’ English lifestyle portrayed through social media provide expert choice and social proof.

4.7. Quality/Performance

Meaning is also important for all four retailers when it comes to the quality and performance of the product, for instance E & K’s emphasis on ‘timeless design’, ‘best of British luxury’ or ‘lovingly hand weave’. Words such as ‘cherish’, ‘beautiful’, ‘individual’ also increase the importance of waste ‘from the cutting room floor’, whilst anthropomorphic phrases such as ‘previously deployed in active duty for 30 years’ provoke empathy through storytelling and personality. The fact that GMD supplies designer dresses increases their importance and scarcity in the eyes of the consumer (as does E & K’s offer of limited editions), whilst celebrity endorsements or a ‘made in Portugal and Italy’ tag guarantee quality and desirability through expert choice for both GMD and TC. TC uses words such as ‘durable’, ‘luxury’, a ‘staple in your wardrobe for years to come’ to provide the consumer with a product in the direction of their interest, and emotional engagement with the promise that it is the ‘antithesis of fast fashion’. WW similarly employs direction and worry resolution to reassure the consumer of their ‘high quality stuff that lasts for years and can be repaired, so you don’t have to buy more of it’.

4.8. Customer Service/Supportive Relationships

The dimension of encouragement seems to be important for establishing good customer service credentials amongst all of the retailers, for instance with GMD’s live chat support and videos or many search terms and E & K’s mailing list, social media or direct mail options. Both of these companies make use of tailoring with personalization or personal shopper and choice of length, rental period and size to make the process easy, and E & K employs transparency by communicating the business’s material sources, processes and purpose in an authentic manner. Emotional engagement is also important for most of the companies for building supportive customer relationships, such as GMD’s catalogue of exciting social occasions for which they can provide dress suggestions or WW’s ‘repair and care’ detailed product guides that give ongoing customer service beyond purchase. WW’s ‘designed to endure’ video uses metaphors such as ‘fabric doctors’, ‘gurus of everlasting thread’ to provoke empathy, and phrases like ‘we take care of each piece by hand’ assuage guilt by emphasizing the company’s focus on care, repair and longevity of items. In a similar way TC uses reciprocation to make customers feel they have been done a favor: ‘if anything happens to it over the next 30 years, send it to us and we will mend it and send it back to you. That means the cost of repair and return postage is on us’—with the 30-year time scale also increasing importance.

4.9. Warranty

TC provides customers with ‘our 30 year guarantee: 3 decades of free mending’, a strategy that increases the importance of the clothing and potentially the effort the user is willing to put into maintaining it, and could also assuage guilt about the purchase or introduce reciprocation. GMD and WW also assuage guilt and provide worry resolution with their obtrusive ‘no risk policy’ (get refunded for unused styles) and ‘Ironclad Guarantee’ (replacement or refund, even for worn items) respectively. ‘Ironclad’ as a metaphor evokes the company’s trustworthiness and may increase customer confidence. E & K also provides a 12-month guarantee for all products, though this is rather hidden on their ‘Terms’ page and does not seem to be part of a marketing strategy, as with the other retailers.

4.10. Peer Testimonials/Reviews

For peer testimonials, the most important design pattern is social proof. Pop-up banners on E & K’s site tell customers every time someone else buys a product; e.g., ‘Adam from Cardiff purchased a tote bag’—whilst WW’s ‘The Stories We Wear’ page is full of customers’ stories of their experiences and memories with their Patagonia gear, emphasizing its quality and longevity and using storytelling to provoke empathy. Media appearances build credibility for E & K, TC and GMD, and celebrity endorsements are particularly important to reinforce the expert choice and importance of TC and GMD’s brands (‘TC have made clothing for the likes of Leonardo DiCaprio, Ben Stiller, Rod Stewart, Hugh Grant...’ etc.). The customer reviews and photos on GMD also provide worry resolution for other customers and reassure them that the fit, look, hassle or price factors will work in their favor.

5. Discussion

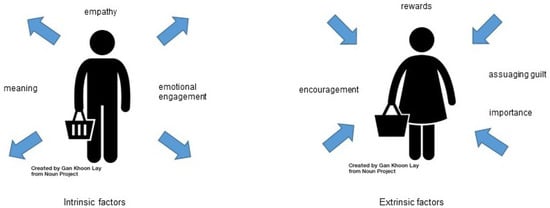

On the whole, extrinsic factors such as cost and warranties seem to be addressed by hedonic dimensions such as rewards, encouragement, assuaging guilt, obtrusiveness and importance, whereas more intangible, intrinsic factors like brand image, environmental impact, quality and contamination are served by eudaimonic dimensions like meaning, empathy and emotional engagement (see Figure 5). All four retailers employ a combination of these.

Figure 5.

Illustration of intrinsic factors addressed by eudaimonic dimensions, and extrinsic factors addressed by hedonic dimensions.

TC, E & K, and WW all have a sense of mission or purpose to their brands and use language and imagery to surprise us or change our perspective, for instance on the length of time that clothes should last and the desirability of ‘old’ products or materials, helping to differentiate themselves as circular businesses from more familiar retailers. Tom Cridland’s own personality as a young British entrepreneur with famous friends, a rock band and a jet-set lifestyle is crucial to the brand, but the media are just as fascinated by his audacious 30-year guarantee and the irony of the ‘anti-fashion’ fashion company. WW and E & K try to change our assumptions about used clothing by employing storytelling, metaphor, personalization and playfulness: WW’s ‘stories we wear’ celebrate the wearing or ‘adventure’ of use for instance, whilst E & K’s ‘rescued’, ‘raw’, ‘cherished’ materials and emphasis on business purpose try to create empathy and convey authenticity, thus helping to transform our preconceptions of the value of waste. GMD as the only PSS model is rather anomalous, and rather than trying to stand out from the crowd, it reassures customers that it is ‘just like a normal shop’, using anchoring and worry resolution to convince us that products are ‘in new condition’ and ‘risk free’. The communication of customer service, cost and convenience are particularly germane to GMD, which also employs tailoring (for a specific event or body type) to persuade consumers to try out this novel service.

This analysis tells us that some strategies from these existing design frameworks may be more relevant than others in assessing communication and marketing in a circular economy context. Patterns from most of the DWI lenses were useful in this study for instance, with more coming from the Cognitive Lens than any other, but some (e.g., Architectural, as mentioned before) being only marginally relevant. The dimensions of control, timing and exposure were discovered to be less relevant than the others for online communications, as it is difficult for companies to exert actual behavioral control using words and images, to affect the timing and context in which a customer views the site, or to influence the number of times people are exposed to their website. Targeted advertising of course is now facilitating the latter, but falls outside the scope of this study. Going through each consumer factor systematically to examine how a company is addressing these using the design dimensions or patterns shows that all four companies were addressing most of the factors, but there were striking differences in the way that they accomplished this. Based on the analysis of the four companies in this study, Table 4 suggests which communication design strategies may be most apt for addressing each consumer concern or ‘factor’ identified in the literature. Of course, the analysis is case-based and subjective and therefore difficult to generalize, and using different design or behavioral models would have given different results. But taking a multi-case approach and verifying the findings between the authors has enabled them to be as reliable as possible, whilst using the consumer factors from literature has focused the analysis on communications that address motivators or barriers for a circular economy.

DfSB approaches have been criticized by practice theorists and those with a more cultural or socio-material approach as too simplistic or encouraging an overly individualized approach that risks rebound effects and does not take enough account of the attitude-behavior gap [76]. However, there are no silver bullets and it would appear that borrowing from DfSB frameworks can provide a useful and more comprehensive scope for analyzing some marketing strategies than has traditionally been offered by the rather binary options of ‘self-other’ green marketing. Environmentally motivated, ‘deep green’ consumers represent only a fragment of the total and therefore appealing to consumers’ emotions and self-interest, as highlighted by the green marketing literature, represents an important and perhaps vital way to engage those consumers who would not be won over by rational or environmental arguments. If consumers are to be engaged not just with new brands and alternative products but with the new behaviors and ways of consuming suggested by a circular economy, then it appears that new types of communication and marketing strategies may also be necessary, and that the field of design may be able to suggest tools and frameworks that provide useful insights.

The paper indicates how these design-based methods of assessment may be useful to businesses in taking a more strategic approach when designing their marketing communications for a circular economy. However, it is impossible to scrutinize properly the success of communication strategies for a circular economy without also examining consumer interpretations, and next steps for the research should also include a consumer perspective on these communications.

6. Conclusions

This study has identified ten groups of factors from circular economy and sustainability literature that may affect consumers’ acceptance of circular economy products and services, and identified two models from design literature that propose strategies for influencing consumer behavior. It has used these factors and strategies as deductive frameworks in mapping and assessing the web communications of four real-life companies with ‘circular’ offerings, and has provided insights into the very different approaches used by each. Design tools such as the Dimensions of Behavior Change or Design with Intent can be useful for analyzing and guiding business communications in the context of a circular economy, by suggesting different strategies that appeal to different aspects of people’s motivations or behavior. Some aspects of these frameworks may be more relevant than others, and depending on the characteristics of specific user groups, may be less or more relevant when aiming to persuade consumers to adopt new behaviors and buy into circular products and services. Nevertheless, certain strategies appear to be the most appropriate for addressing specific consumer concerns (see Table 4), and we regard this as a novel contribution to emerging research on how to introduce and communicate circular offers to users in a successful way. An advantage over common marketing and branding approaches is that our recommendations not only focus on how to communicate ready designed product and services, but also provide insight for the very design process thereof, taking behavioral aspects into account and providing a more nuanced and detailed palette through the application of design frameworks than have hitherto been available to green marketing or social marketing. We recommend future research to apply and test these in various scenarios to provide greater insight and new opportunities for companies wishing to do so. Such dedicated case studies will also provide insight into the profitability and market feasibility of such strategies, both on a product and company level. This will enable companies to gain further insights into potential trade-offs between sustainability criteria, market share, profitability, and company image.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.C. and C.B.; Methodology, L.C.; Validation, L.C. and C.B.; Formal Analysis, L.C.; Writing-Original Draft Preparation, L.C.; Writing-Review & Editing, C.B.

Funding

This research was partly funded by the EU Marie Curie Innovative Training Network CIRC€UIT.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our close colleagues Juana Camacho-Otero and Ida Nilstad Pettersen for their input. This research did not receive any support from commercial actors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Categorization of Examples from the Websites

Table A1.

Summary of examples from Tom Cridland website. Which consumer factor does each address, and which design dimension or DwI pattern does it use to affect this?

Table A1.

Summary of examples from Tom Cridland website. Which consumer factor does each address, and which design dimension or DwI pattern does it use to affect this?

| ‘What’ | ‘How’ | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Consumer Factor | Examples of Factor Being Addressed in Digital Marketing | Dimension of Behavior Change | Design with Intent Pattern |

| Awareness | |||

| Contamination/Disgust/Newness | n/a | ||

| Convenience/availability | Free global shipping over 150 pounds Payment in 6 currencies Returns &exchanges | Encouragement Empathy | |

| Ownership | n/a | ||

| Cost/financial incentive/value | ‘..will save you money in cost per wear’ | Encouragement | Rewards Assuaging guilt |

| Environmental impact | ‘A campaign against planned obsolescence’ gives the brand purpose and values | Meaning Empathy | Framing Storytelling Emotional engagement |

| Brand recognition/image/design/intangible value | ‘The world’s number 1 sustainable fashion brand’ is a bold claim Likewise the 30 year t-shirt/sweatshirt/jacket. These bold statements, and the striking black and white logo with contrasting colorful clothing, create a strong brand. Media endorsements and PR are also very important for this brand ‘From London to Hollywood’: Tom’s personality, celebrity friends, rock band, PR company and upper-class English lifestyle portrayed through social media are integral to the brand | Obtrusiveness Importance Meaning | Mood Prominence Expert choice Storytelling |

| Quality/performance | ‘Durable, luxury clothing at an affordable price point’ ‘Made in Portugal and Italy’—recognized as centers of fine quality fabrics and manufacturing The ‘antithesis of fast fashion’ ‘A staple in your wardrobe for years to come’ | Meaning Direction | Expert choice Storytelling Emotional engagement |

| Customer service/communication/supportive relationships | ‘… If anything happens to it over the next 30 years, send it to us and we will mend it and send it back to you. That means the cost of repair and return postage is on us.’ | Meaning Direction | Emotional engagement Reciprocation |

| Warranty | ‘Our 30 year guarantee’: 3 decades of free mending | Encouragement Obtrusiveness | Assuaging guilt Reciprocation |

| Peer testimonials/reviews | Quotes from global media (The Journal) and celebrity endorsements reinforce the credibility of the brand (‘TC have made clothing for the likes of Leonardo DiCaprio, Ben Stiller, Rod Stewart, Hugh Grant, Danny McBride, Frankie Valli, Stephan Merchant, Jeremy Piven, Nigel Olsson, Brandon Flowers, Robbie Williams, Daniel Craig, Clint Eastwood and Kendrick Lamar’) | Importance Obtrusiveness Meaning | Expert choice Social proof |

Table A2.

Summary of examples from Girl Meets Dress website. Which consumer factor does each address, and which design dimension or DwI pattern does it use to affect this?

Table A2.

Summary of examples from Girl Meets Dress website. Which consumer factor does each address, and which design dimension or DwI pattern does it use to affect this?

| ‘What’ | ‘How’ | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Consumer Factor | Examples of Factor Being Addressed in Digital Marketing | Dimension of Behavior Change | Design with Intent Pattern |

| Awareness | |||

| Contamination/Disgust/Newness | Dry cleaning is mentioned, but otherwise the issue of contamination (by others having worn the dress first) is conspicuous by its absence | ||

| Convenience/availability | ‘Dry cleaning is on us’ ‘Next day delivery’ Order and try on up to 3 dresses’ ‘4000+ new season dresses, 150+ brands’ ‘Rent a different designer dress for all your events’ ‘Risk free’, ‘get a refund for anything you don’t wear’ ‘4 simple steps to rent the dress of your dreams’ | Encouragement Empathy Meaning Direction | Worry resolution Assuaging guilt |

| Ownership | GMD reassures customers to try this rental system by reassuring them that it is the same as the ownership system they are used to, e.g., they receive a refund for anything unworn ‘just like any normal shop’, or can try on lots of options, ‘just like a normal shop’ | Encouragement Empathy | Framing Anchoring |

| Cost/financial incentive/value | ‘Free stylist advice’, ‘First Dress Free’, ‘Get this dress free’—the word free is used frequently, often combined with bright pink and capital letters for emphasis. 10 pound welcome gift plus money off first order. | Encouragement | First one free Rewards Expert choice |

| Environmental impact | n/a | ||

| Brand recognition/image/design/intangible value | Lots of colorful images of women having fun and at parties Bright pink suggests excitement and parties ‘Join the Club’ suggests an element of exclusivity | Meaning direction | Emotional engagement Mood Color associations Storytelling Scarcity |

| Quality/performance | These are designer dresses Refund for anything unworn, ‘just like any normal shop’ | Meaning Importance | Expert choice Scarcity |

| Customer service/communication/supportive relationships | ‘Order online or book a showroom appointment’ Suggestions of dresses for different scenarios, e.g., The Races, Girls’ Night Out, Wedding Guest, live chat support and videos, many different search terms, Personal Shopper, choice of length, size, rental period etc.—all make the process seem easy ‘Our priority is that you look and feel amazing’ | Encouragement Meaning Empathy | Emotional engagement Social proof Tailoring |

| Warranty | No risk policy (try a few styles and get refunded for the ones that don’t fit) | Encouragement Direction | Assuaging guilt Worry resolution |

| Peer testimonials/reviews | Media mentions build credibility Celebrity endorsements likewise Customer reviews and photos reassure others in terms of hassle, fit, look, price etc. | Meaning Importance | Expert choice Social proof Provoke empathy Worry resolution |

Table A3.

Summary of examples from Patagonia Worn Wear website. Which consumer factor does each address, and which design dimension or DwI pattern does it use to affect this?

Table A3.

Summary of examples from Patagonia Worn Wear website. Which consumer factor does each address, and which design dimension or DwI pattern does it use to affect this?

| ‘What’ | ‘How’ | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Consumer Factor | Examples of Factor Being Addressed in Digital Marketing | Dimension of Behavior Change | Design with Intent Pattern |

| Awareness | |||

| Contamination/Disgust/Newness | Homepage headline ‘Better than New’ is a surprising way of describing old clothes Likewise ‘Scars tell the story’ anthropomorphizes the clothes | Meaning Importance Empathy | Rephrasing & renaming Playfulness Provoke empathy Personality |

| Convenience/availability | ‘We wash it’ ‘Trade in at a store near you’ | Encouragement | Reciprocation |

| Ownership | n/a | ||

| Cost/financial incentive/value | ‘You get paid’ ‘See how much your clothes are worth’ Customers are encouraged to see their waste as valuable, and a list of trade-in values is available as a download | Encouragement Importance | Rewards |

| Environmental impact | ‘Keep the Worn Wear Cycle in Motion and Avoid the Landfills’ | Importance Direction | Emotional engagement Assuaging guilt |

| Brand recognition/image/design/intangible value | ‘Retro’ imagery and coloring evoke the values of a previous age and Patagonia’s emphasis on repair, reuse, and quality Partnership with iFixit reinforces Patagonia’s values-based emphasis on repair | Meaning Empathy | Storytelling Mood Color associations Provoke empathy |

| Quality/performance | Homepage mention of ‘high quality stuff that lasts for years and can be repaired, so you don’t have to buy more of it’ spells out the company’s commitment to quality, and consideration of the customer’s time and money | Empathy Direction | Worry resolution Assuaging guilt |

| Customer service/communication/supportive relationships | ‘Repair and Care’ detailed product repair and care guides provide ongoing customer service after purchase. Designed to Endure’ video (terms such as ‘fabric doctors’, ‘gurus of everlasting thread’, ‘we take care of each piece by hand’ emphasize the company’s expertise and focus on care, repair and longevity of items) | Empathy Encouragement Direction | Emotional engagement Metaphors Rephrasing &renaming Assuaging guilt |

| Warranty | Patagonia’s Ironclad Guarantee offers replacement or refund, even for worn items | Encouragement | Assuaging guilt Metaphors (‘ironclad’ evokes Patagonia’s trustworthiness) |

| Peer testimonials/reviews | ‘The Stories We Wear’ page is full of customers’ stories of their experiences and memories with their Patagonia gear, emphasizing its quality and longevity | Meaning Empathy | Storytelling Provoke empathy Social proof |

Table A4.

Summary of examples from Elvis & Kresse website. Which consumer factor does each address, and which design dimension or DwI pattern does it use to affect this?

Table A4.

Summary of examples from Elvis & Kresse website. Which consumer factor does each address, and which design dimension or DwI pattern does it use to affect this?

| ‘What’ | ‘How’ | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Consumer Factor | Examples of Factor Being Addressed in Digital Marketing | Dimension of Behavior Change | Design with Intent Pattern |

| Awareness | |||

| Contamination/Disgust/Newness | ‘Rescued raw materials’, ‘decommissioned’ fire hose, ‘reclaimed’ banners, ‘re-engineered’ blankets: the word choice anthropomorphizes used or second hand materials to bring about a new perspective and elicit customers’ sympathy and emotional connection with the materials. ‘Each bag unique’: non-uniform waste materials are reframed as one-off exclusive pieces. Fire hoses have a ‘distinguished career’ and ‘eventually get retired’, are a ‘heroic material’ which make an ‘exciting alternative textile’ | Empathy Meaning | Provoke empathy Emotional engagement Rephrasing &renaming Framing |

| Convenience/availability | ‘You don’t need to worry’: bags are wipe clean, keep contents dry, big enough for a laptop etc. | Empathy Encouragement | Worry resolution |

| Ownership | n/a | ||

| Cost/financial incentive/value | High cost of product implies its status as valuable material rather than waste Limited edition | Importance | Framing Scarcity |

| Environmental impact | E & K are honest about the recycled source of their materials, ie fire hose, printing blankets, parachute silk, coffee sacks, leather Re-engineer ‘seemingly useless wastes’, ‘rescue’ and ‘individually cut’ and ‘lovingly hand weave’ these wastes | Empathy Obtrusiveness | Transparency Emotional engagement |

| Brand recognition/image/design/intangible value | ‘Rescue, Transform, Donate’, ‘We love to share’: the cycle of rescuing materials and donating profits is key to the brand, as are values -‘Sustainable luxury’, ‘ethical travel’ etc. Also the story: ‘Our Story’ page with video ties in brand with emotive story of firefighters and rescue and highlights its purpose beyond profitmaking. E & K is the ultimate rescuer by saving materials from waste and helping firefighters charities. Earthy colors evoke the fire/firefighters/rescuers and natural materials that are key to the brand. E & K’s accreditations (B-Corp member, Positive Luxury, Brand of Tomorrow, Women’s Initiative etc.) communicate its purpose-driven status | Meaning Empathy Importance | Mood Storytelling Transparency Emotional engagement |

| Quality/performance | ‘Previously deployed in active duty for 30 years’—anthropomorphic phrases liken the materials to the people that used them, give them a story and reassure customers of their durability Limited edition products also imply quality ‘Timeless design’, ‘hardwearing’, ‘a whole new kind of luxury’—rescued and hand crafted, ‘beautiful leather’, ‘we lovingly hand weave’ | Meaning Importance Empathy | Metaphors Provoke empathy Scarcity Storytelling |

| Customer service/communication/supportive relationships | Mailing list, social media and direct mail contacts as well as a personalization service are all available. The communication of the business and its mission seems authentic and transparent, both in terms of material sourcing and genuine care for the customer experience | Encouragement | Tailoring |

| Warranty | |||

| Peer testimonials/reviews | Pop-up banners on the site tell customers every time someone else buys a product, e.g., ‘Adam from Cardiff purchased a tote bag’. News page lists public appearances and media mentions and makes clear the company’s purpose-driven ethos (‘doing good is doing well’), showing its status as more than a retailer | Empathy Importance | Social proof Expert choice |

References

- Steffen, W.; Richardson, K.; Rockström, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Fetzer, I.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; Carpenter, S.R.; de Vries, W.; de Wit, C.A.; et al. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 2015, 347, 1259855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Towards the Circular Economy 1.; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Cowes, Isle of Wight, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tukker, A. Product services for a resource-efficient and circular economy: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 97, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piscicelli, L.; Ludden, S. The potential of Design for Behaviour Change to foster the transition to a circular economy. In Proceedings of the DRS 2016, Design Research Society 50th Anniversary Conference, Brighton, UK, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, A. The Century of the Self (Full Documentary); BBC: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke, D.; Lollo, N. Transforming Consumption: From Decoupling, to Behavior Change, to System Changes for Sustainable Consumption. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2015, 40, 233–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Short, S.W. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions Towards a sufficiency-driven business model: Experiences and opportunities. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2016, 18, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antikainen, M.; Lammi, M.; Rüppel, H.P.T.; Valkokari, K. Towards Circular Economy Business Models: Consumer Acceptance of Novel Services. In Proceedings of the The ISPIM Innovation Summit, Brisbane, Australia, 6–9 December 2015; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Schotman, H.; Ludden, G.D.S. User acceptance in a changing context: Why some product-service systems do not suffer acceptance problems. J. Des. Res. 2014, 12, 188–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boks, C. An Introduction to Design for Sustainable Behaviour. In Routledge Handbook of Sustainable Design; Egenhoefer, R.B., Ed.; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Klöckner, C.A. The Psychology of Pro-Environmental Communication; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sakao, T.; Brambila-Macias, S.A. Do we share an understanding of transdisciplinarity in environmental sustainability research? J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 170, 1399–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Hollander, M.C.; Bakker, C.A.; Hultink, E.J. Product Design in a Circular Economy Development of a Typology of Key Concepts and Terms. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, C.; Hollander, M.C.; van Hinte, E.; Zijlstra, Y. Products That Last: Product Design for Circular Business Models; TU Delft Library/Marcel den Hollander IDRC: Delft, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; de Pauw, I.; Bakker, C.; van der Grinten, B. Product design and business model strategies for a circular economy. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2016, 33, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N. Business-led sustainable consumption initiatives: Impacts and lessons learned. J. Manag. Dev. 2017, 36, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, T.B.; Riisberg, V. Cultivating User-Ship? Developing a Circular System for the Acquisition and Use of Baby Clothing. Fash. Pract. 2017, 9, 216–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.C. Customer Networks Increase Adoption of New Products. BI Mark. Mag. 2014, 1, 14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Rex, E.; Baumann, H. Beyond ecolabels: What green marketing can learn from conventional marketing. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P. Principles of Marketing; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kohli, A.K.; Jaworski, B.J. Market Orientation: The Construct, Research Propositions, and Managerial Implications. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, S. Consumers and Their Brands: Developing Relationship Theory in Consumer Research. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 24, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, W. Advertising—A Very Short Introduction; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- King, R.; Schilhavy, R.; Chowa, C.; Chin, W. Do Customers Identify with Our Website? The Effects of Website Identification on Repeat Purchase Intention. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2016, 20, 319–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKelvey, K. Chapter 30—The Marketing of Fashion. In Textiles and Fashion; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 763–797. [Google Scholar]

- Groening, C.; Sarkis, J.; Zhu, Q. Green marketing consumer-level theory review: A compendium of applied theories and further research directions. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 1848–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangelico, R.M.; Vocalelli, D. ‘Green Marketing’: An analysis of definitions, strategy steps, and tools through a systematic review of the literature. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 165, 1263–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.; Schouten, J. The answer is sustainable marketing, when the question is: What can we do? Rech. Appl. Mark. 2014, 29, 107–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K.; Peattie, S. Social marketing: A pathway to consumption reduction? J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Zhang, L.; Xie, G.-X. Message framing in green advertising: The effect of construal level and consumer environmental concern. Int. J. Advert. 2015, 34, 158–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segev, S.; Fernandes, J.; Wang, W. The Effects of Gain Versus Loss Message Framing and Point of Reference on Consumer Responses to Green Advertising. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2015, 36, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimmer, M.; Woolley, M. Green marketing messages and consumers’ purchase intentions: Promoting personal versus environmental benefits. J. Mark. Commun. 2012, 20, 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Lu, Y.; Zhu, W.; Su, C. Going green: How different advertising appeals impact green consumption behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 2663–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthes, J.; Wonneberger, A.; Schmuck, D. Consumers’ green involvement and the persuasive effects of emotional versus functional ads. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1885–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, R.E. Limits to labels: The role of eco-labels in the assessment of product sustainability and routes to sustainable consumption. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2009, 33, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boks, C. The soft side of ecodesign. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 1346–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K.; Crane, A. Green Marketing: Legend, myth, farce or prophesy? Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2005, 8, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, J. The Green Marketing Manifesto; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: Chichester, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Zaltman, G. Social Marketing: An Approach to Planned Social Change. J. Mark. 1971, 35, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenzie-Mohr, D. Social Marketing to Protect the Environment: What Works; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Lee, N. Social Marketing: Influencing Behaviors for Good, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Londen, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, P.W. Strategies for Promoting Proenvironmental Behavior Lots of Tools but Few Instructions. Eur. Psychol. 2014, 19, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Lee, N. Best of Breed: When it Comes to Gaining A market Edge while Supporting a Social Cause, Corporate Social Marketing Leads the Pack. Soc. Mar. Q. 2005, 11, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daae, J.; Boks, C. Opportunities and challenges for addressing variations in the use phase with LCA and Design for Sustainable Behaviour. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2015, 8, 148–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klöckner, C.A.; Blöbaum, A. A comprehensive action determination model: Toward a broader understanding of ecological behaviour using the example of travel mode choice. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 574–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilley, D.; Lofthouse, V.A.; Bhamra, T. Towards instinctive sustainable product use. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference in Sustainability, Creating the Culture, Aberdeen, UK, 2–4 November 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, Fast and Slow; Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, E.F.; She, J. Seven cognitive concepts for successful eco-design. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 92, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heskett, J. Design and the Creation of Value; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kress, G.R.; Van Leeuwen, T. Multimodal Discourse: The Modes and Media of Contemporary Communication; Arnold: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Daae, J.Z.; Boks, C. Dimensions of behaviour change. J. Des. Res. 2014, 12, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockton, D.; Harrison, D.; Stanton, N.A. Design with Intent: 101 Patterns for Influencing Behaviour through Design; Equifine: Windsor, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Abbey, J.D.; Meloy, M.G.; Blackburn, J.; Guide, V.D.R. Consumer Markets for Remanufactured and Refurbished Products. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2015, 57, 26–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhi, F.; Eckhardt, G.M. Access-Based Consumption: The Case of Car Sharing. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 39, 881–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boks, C.; Galjaard, S.; Huisman, M.; Wever, R. Customer Perception of Buying New but Unpacked Electronics Products. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Electronics and the Environment, 2004, Scottsdale, AZ, USA, 10–13 May 2004; pp. 270–274. [Google Scholar]

- Van Weelden, E.; Mugge, R.; Bakker, C. Paving the way towards circular consumption: Exploring consumer acceptance of refurbished mobile phones in the Dutch market. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 113, 743–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmström, S.; Böhlin, H.; Biedenbach, G. Towards a Circular Economy: A Qualitative Study on How to Communicate Refurbished Smartphones in the Swedish Market. Student Thesis, Umeå School of Business and Economics, Umeå, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mugge, R.; Jockin, B.; Bocken, N. How to sell refurbished smartphones? An investigation of different customer groups and appropriate incentives. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 147, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catulli, M.; Lindley, J.K.; Reed, N.B.; Green, A.; Hyseni, H.; Kiri, S. What is Mine is NOT Yours: Further insight on what access-based consumption says about consumers. In Consumer Culture Theory; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, W.; Aurisicchio, M.; Childs, P. Contaminated Interaction: Another Barrier to Circular Material Flows. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Otero, J.C.; Pettersen, I.N.; Boks, C. Consumer and user acceptance in the circular economy: What are researchers missing? PLATE 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.; Griffith, S.; Giorgi, S.; King, G. Resources, Conservation and Recycling Consumer understanding of product lifetimes. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2013, 79, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindström, J.; Nilsson, K.; Parida, V.; Rönnberg, D.; Ylinenpää, H.; Boucher, X. Sustainable management of operation for Functional Products: Which customer values are of interest for marketing and sales? Procedia CIRP 2015, 30, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, T.; Folkerson, M. Industrial Evolution—Making British Manufacturing Sustainable; Manufacturing Commission: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Guiot, D.; Roux, D. A Second-hand Shoppers’ Motivation Scale: Antecedents, Consequences, and Implications for Retailers. J. Retail. 2010, 86, 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukker, A. Eight Types of Product—Service System: Eight Ways to Sustainability? Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2004, 13, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cresswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design. Choosing Among Five Approaches; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2011, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo, B.; Gopaldas, A.; Fischer, E. The construction of qualitative research articles: A conversation with Eileen Fischer. Consum. Mark. Cult. 2017, 20, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R.; Fischer, E.; Kozinets, R. Approaches to Data Analysis, Interpretation and Theory Building for Scholarly Research. In Qualitative Consumer and Marketing Research; Sage: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Foulds, C.; Morosanu, R. Controlling Busyness: The Promises of Smart Home Industry Discourses. In Daily Life, Digital Technologies and Energy Demand—A Working Paper Collection; Macrorie, R., Wade, F., Eds.; Urban Institute, University of Sheffield: Sheffield, UK, 2016; pp. 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Selzer, J. Rhetorical Analysis: Understanding How Texts Persuade Readers. In What Writing Does and How It Does It: An Introduction to Analyzing Texts and Textual Practices; Bazerman, C., Prior, P., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen, I.N.; Boks, C.; Tukker, A. Framing the role of design in transformation of consumption practices: Beyond the designer-product-user triad. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2013, 63, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).