1. Introduction: The Tourist City within the Framework of Neoliberalism

At the beginning of the 1970s, the decline in profit rates and the overaccumulation of capital fueled an economic crisis. Thereafter, neoliberalism was imposed as mainstream economic and political policy, as well as an upper echelon project to restore the capital gains rate [

1]. The shock of the crisis was used as a rationale to apply measures for global restructuring and de-industrializing the central economies, which generated unemployment in those populations. The state assumed a new role that favored accumulating capital, which led to regulation for creating an environment that is favorable to growth and investment. Neoliberalism promulgates greater efficiency of the private sector, the flexibilization of the regulatory framework, and the reduction of taxes. In this way, wealth is not redistributed to the state but instead trust is placed in the trickle-down theory of economics. Thus, competitiveness is the pattern of behavior that guides relationships between people, companies and territories.

With the bursting of the financial and real estate bubble, the 2008 crisis fostered profit-seeking through buying up natural resources, land and debt. Regarding tourism, capital took advantage of the crisis to intensify class relations and restructure the tourism sector [

2]. The deindustrialized city became prey to a resurgence in tourism, for which its civic culture was commodified through the marketing of the city [

3]. The inclusion of new elements is more lucrative, so this process hits specific goods rather hard, such as those that are scarce like housing; that are common, like public spaces; or that are iconic collective capital generated by social cohesion. This unique offer creates interest in urban spaces that have remained on the periphery of the tourist market and who have attentively preserved their social and cultural structures as well as their civitas [

4]. The “touristification of the everyday” [

5] implies the emergence of conflicts from social segregation, inflation, congestion, privatization and the trivialization of spaces [

6]. The commodification of the multifunctional city—as opposed to a monofunctional Fordist tourist resort—provides capital from monopolistic rents based on policies that impose limitations and make it unique. Paradoxically, as social tensions emerge and authorities seek to impose limits on homogenizing mass tourism, this contributes to creating a city brand that differentiates and distinguishes itself, thus making it even more attractive and more profitable to capital [

7].

The economic, social and environmental conditions, which induce the future sustainability of any development model, are altered by the intensification of the tourist use of the traditional city. Accommodation capacity, for residents and for tourists, is one of the key variables for measuring the sustainability of a territory. This variable will determine its consumption of energy, water and materials or the generation of waste [

8]. Consequently, a first and substantial way of measuring sustainability is the analysis of dwelling development and management. Sustainability could be achieved, in this sense, through the application of urban planning and management measures that could improve the living conditions of the local population, such as their need for housing and business profitability, and contribute to improve the quality of the tourist experience.

Ten years after the explosion of the real estate bubble (2008) that caused the current crisis, some Spanish cities are experiencing a rise in housing rental prices. This rise in prices responds to economic cycles, as has been discussed by other authors [

2]. The moments of cyclical acceleration that inflate bubbles are similar not only from the financial point of view, but also in terms of social consequences of the segregation of the population with low income levels. This is why we use the term bubble for the rise in housing rental prices. We use the term bubble for the rising prices of housing rental, not only from the point of view of a feasible speculative processes when trade in an asset at a price or price range strongly exceeds the asset’s intrinsic value that are typical of finance capitalism; but we also widen the sense of bubble to the social struggle associated with the incarceration of housing rents. The aim of this paper is to complement the definition of the housing rental bubble by offering the case study of Barcelona to illustrate explanatory factors for this feasible rental housing bubble. The current economic model views housing and public space as a business and not as a fundamental right of people. These mercantile dynamics prioritize the accumulation of capital for business profit over the welfare of the population. Housing business thus transforms neighborhoods into “window displays” to satisfy the needs of tourists and feed economic appetites. The housing rental prices’ rise accentuates the segregation between neighborhoods, alters their original identity, deteriorates their social cohesion and commodifies public spaces. These processes place at risk neighborhood social structures that are new tourist attractions themed around “everyday urban life”.

The liberalization of trade and the movement of capital feed the restructuring of tourism as different places compete to attract investment. New York initiated policies of urban entrepreneurship as early as the 1980s, publicizing its city brand (I Love NY) and promoting its attraction to financial, insurance and real estate interests (commonly known by their acronym FIRE). Following the same model, other territories, and particularly cities, seek to create their brand image and identity in this struggle to offer profitability to capital investment and provide unique tourist consumer products [

9].

Planning is made more flexible so that it can adapt to the requirements of neoliberal re-regulation. This is because capital requires advantages that can only be achieved through the legitimacy of planning in order to impose market discipline through the power of the state [

10]. This urban entrepreneurism helps to better understand the transformation of the city for tourism, which is clearly demonstrated by the commodification of public spaces [

11] and, above all, housing [

12]. The hegemony of the property market, which has long been successful at attracting capital and tourists, leads to significant imbalances in income, dispossession and displacement of the low-income population. Substituting certain social classes for those with higher purchasing power leads to gentrification processes [

13]. The so-called “tourist bubble” is fed by the crisis occurring among the peripheral states of the European Union, with a particular impact on Spain [

2]. In this context, the “rent bubble” is expanding and affecting large European and American cities [

14]. In Spain, this phenomenon has been exacerbated by structural aspects of the property market and the lease of housing, mainly urban, as we will see below.

The intensification of the tourism function of cities, within the context of their entrepreneurial management and place marketing [

15], is being linked to increasing housing rental prices [

16,

17]. This process deals with the gentrification of the city [

18], motivating social movements claiming rights to the city [

19]. The criminalization of tourism is associated with social reactions to overtourism with antitourism [

20] that are rooted in the class struggle within the crisis [

3]. Tourist housing rental has already been associated with the deterioration of labor conditions [

21], decreasing profitability of the hotel industry [

22], finance and real estate speculation [

23] and to the consequences of neoliberal urban policies [

15]. The contribution of this study aims to demonstrate that there are other factors, in addition to tourism, that favor the rising prices of rental housing, explain social movements’ reactions and the attempts to apply palliative measures by the local public administration.

Within this context, our main research questions aim to fill the gaps in available academic knowledge. First, is tourism the only factor responsible for this housing prices increase? Second, is it possible to develop local administration policies to palliate this conflict? The aims of our paper in order to answer these questions are: first, to offer an overview of housing rental market evolution in Spain; second, analyzing the explanatory factors of the rental housing prices increases, in order to support the proposal of the existence of a price rise and how the increasing tourist function of the cities contributes to this process; third, to illustrate the explanatory factors of this process with the case of Barcelona; fourth, to describe social movements’ reactions to overtourism; and fifth, to describe the local policies of urban and tourism planning developed by Barcelona’s government.

2. Methodology

A mixed methodology (quantitative and qualitative) was used. At the qualitative level, a detailed analysis of the secondary sources was carried out with a focus on extant studies conducted by different stakeholders: public administrations, private real estate agents and social entities involved in the phenomenon. Also at a qualitative level, in-depth interviews were conducted with different stakeholders and qualified informants (residents, business owners, and administration) and participant observation was utilized in sector associations to meet objectives 4 and 5. Among them are those responsible for carrying out the administrative policies in Barcelona (Director of the Strategic Plan for Tourism), activists in residents’ associations such as the ABTS (Spanish acronym for the Assembly of Neighborhoods for Sustainable Tourism) and residents of the neighborhoods most affected by the phenomenon.

At the quantitative level, the secondary sources used—mainly aimed to fulfil the objective number one—were primarily official statistics compiled by public administrations (Barcelona City Council, Generalitat de Catalunya, Incasol, the Housing Board, INE, Idescat, and others), as well as those offered by private entities in the sector (Idealista, for example). In addition, two opinion polls at street level were conducted, one aimed at residents of areas that in recent years have been most affected by the tourist phenomenon in Barcelona (35 questionnaires to residents of the Ciutat Vella district) and the second to 30 tourists in the city’s downtown neighborhoods (La Barceloneta, El Raval and the Gothic Quarter). The questionnaires and in-depth interviews are on file at the TUDISTAR research group headquarters, at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. They can be consulted by contacting us (tudistar@uab.cat). The triangulation of the various sources and information has allowed a global analysis of the phenomenon.

In this context and aiming to fulfil objectives number two, three and five, first this article carries out a review of the state of the matter, through a review of academic and grey literature, and presents a concise theoretical framework of these processes, as exemplified in the city of Barcelona. In essence, the development of regulations in the neoliberal tourist city is shown first. Second, the factors fueling the housing “rent bubble” are explained in a way that attempts to go beyond the impact that platforms like Airbnb, Homeaway, Niumba, and Wimdu have on the prices of rental housing in touristified cities, which several studies have already shown [

16,

18,

24]. Third, we characterize the conflicts and citizen resistance in the face of touristification. Finally, we analyze some of the public planning and management policies developed by tourist cities aiming to alleviate these conflicts.

3. The ‘Rent Bubble’ in Spain

Beginning in the twentieth century’s decade of the sixties, Spain became one of the European Union countries with a high level of home ownership. The acquisition of housing favors an increase in the nominal values of domestic wealth, which exerts a “wealth effect” that stimulates consumption and debt [

25]. This distinctive feature is a reaction mainly to the shortage of rental homes to accommodate migrant workers who settled in the large industrialized cities [

26]. Thus, Spain’s 78.2% ownership rate presently makes it one of the European Union countries with the highest percentage (the EU average is 69.5%, according to Eurostat data 2017) [

27] following Romania, Croatia, Lithuania, and others.

The culture of home ownership in Spain and the prejudices of the Spanish population against renting have changed following the crisis, due to the serious problems of foreclosures resulting from non-payment of debts and the difficulties in accessing new mortgages. Rental housing is emerging as a reasonable option in the face of purchasing difficulties, and increasing housing rentals in the Barcelona municipality provide a perfect demonstration of this “rent bubble” phenomenon.

Obtaining data and analyzing the evolution of rental income in Spain is an arduous task because official statistics are lacking. The latest data from the Continuous Household Survey of INE (the only one currently in existence) show that the rental population in 2017 represents 22.7% of Spanish households compared to 7% 10 years before; although, this is still far from figures such as those of Germany, 48.3%, or the United Kingdom, 36.6% [

27,

28]. The increase in the population’s demand for rental housing and the buying-up of homes for tourist use imply that we are beginning to see a new “rent bubble”. This process has ranked Barcelona as one of the European Union cities with the lowest available housing stock. Added to this scarcity is the increase in rental prices that the city suffered in 2017 compared to 2016, mainly in Autonomous Communities such as Catalonia (17.2%), Canarias (11.6%) and Madrid (11.4%). In some cases, it exceeded these figures, such as in the Balearic Islands (with a 1.4% year-on-year growth rate) or Catalonia (1.3%), representing the maximums of the years with the greatest effervescence in the real estate sector [

28].

In Barcelona, residential rental has increased in recent years and currently accounts for 30% of existing housing. This change in trend has led to a 23% increase in rental income between 2013 and 2016 [

29]. There was an increase of 10.12% per square meter in 2016 [

30] before it stabilized in the last quarter of 2017.

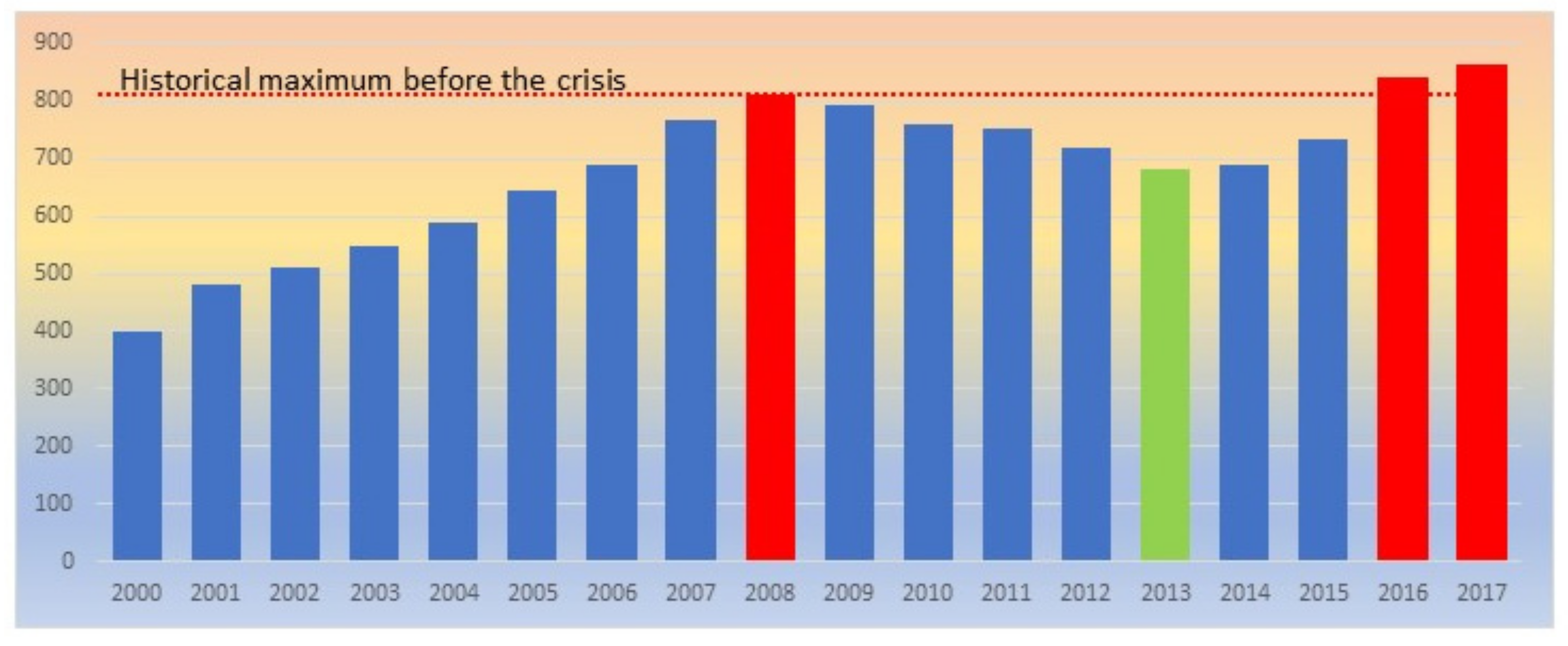

According to real estate studies (Idealista, among others), available rents in Barcelona that are below €600/month now represent less than 1% of the total, and only 5% are below €800/month (

Figure 1). Mean inflation in this period (2000–2017) has been 2.2%, accordingly this factor has not a relevant influence in the housing rental prices. In terms of housing rental prices, these data place Barcelona higher than Madrid, Prague, Munich and Berlin [

31]. Given these figures, it is necessary to consider the differential cost of living and purchasing power between the different aforementioned cities.

This price escalation began in early 2015 and is intensifying the process of gentrification that the whole city of Barcelona has been experiencing since 2005 [

18,

33]. The increase in rental prices means that at present the percentage of income that the population dedicates to housing in many cases reaches unsustainable levels for the household economy. It is estimated that 4 out of 10 tenants spend more than 40% of their rent on housing [

34]. This means that 43.3% of the Spanish population residing under a lease is “financially overexposed” to the expenses derived from housing, mainly in Communities such as the Balearic Islands, Catalonia and Madrid, which are those that that have been most affected by the urban tourism phenomenon [

28].

Public housing policies differ according to the political color of the different territories. Some municipal councils, such as Barcelona, propose measures for controlling, limiting and imposing possible sanctions for abuses in rental prices. On the other hand, the Government of Catalonia has formulated the so-called rental price index, which is promoted by Barcelona as an information and control provision for measuring the disproportionate growth of rents and the lack of market transparency [

35]. On the other hand, the central government promotes the liberalization of the housing rental market through the new Law 4/2013 on Flexibility Measures and Promotion of the Housing Rental Market, which is a modification of Law 29/1994 on Urban Leases. To compensate for its rent-increasing effects, it proposes including measures in the State Plan 2018–2021 that, specifically, will increase the supply of real estate available for rent and provide incentives for tenants and vulnerable groups such as young people and the elderly.

However, the emergence of “the real estate rent price rise” is not only due to an actual increase in the value of real estate, nor to the increase in demand arising from changes in the habits of its population or the current scarce supply. To the factors we must add: the almost null presence of public rental housing; the increase in the floating population temporarily residing in cities such as Barcelona and Madrid; the pressure on housing purchases from foreign investment capital that has clear and selective speculative intentions; and stakeholders of properties in Spanish localities who have either a direct or indirect interest in tourism and the recent increase in the supply of housing used for tourism (HUT).

If we focus on cities such as Barcelona, one third of current home purchases (more than 100 properties as of December 2017) are financed by investment funds, whose objective is to maximize profits [

29]. The central government has attracted these large companies in the form of SOCIMIS (Sociedades Cotizadas Anónimas del Mercado Inmobiliario, the Spanish form of a Real Estate Investment Trust), which rely on great tax advantages. In this way, Barcelona has ranked fourth (behind New York, Berlin and London) as a city of global interest for investors in French, Israeli and Chinese SOCIMIS, mainly in the downtown neighborhoods of the city, where the investments are in whole buildings for tourist rental. Some examples of SOCIMIS are: Norvet Negotial, Merlin Properties, Socinvest Amistad S.L., P4A Barcelona S.L., Aubert Aubert Associés, DSRA Realestate Investments, Galla Inv, City Espresso Bar BCN, RSG Batomeu Sis and Jilong SLU.

The largest increase in Barcelona rental prices occurred in 2013, when the recovery began after the 2008 crisis, and the increases in prices exceeded 25% on average until they stabilized in 2017. This increase explains the expulsion of Barcelona residents, who have had to move to municipalities in what is known locally as the “second metropolitan crown” (an area comprising 129 municipalities surrounding a group of nearby cites). This occurred from 2013 onward, after the legal modification forced them to renew their leases at a higher price at the end of a three-year contract period.

The economic crises have had a cyclical impact on housing prices in Barcelona. They occurred at the end of the 70s, with the crisis of the Fordist regulatory regime; again, in the mid-1990s as a result of the obvious speculation taking place in relation to the 1992 Olympics; and more recently in 2007 with the gentrification processes [

36] that are expelling the disadvantaged classes from the downtown neighborhoods due to increases in rental prices.

The mixed-capital companies dedicated to urban development [

37] are public-private partnerships that have once again proposed strategies to recreate urban rent-seeking. Thus, public capital is used to remodel the city while favoring the profitability of private capital investments [

38]. In these processes, the resident population is displaced by inhabitants who have greater purchasing power. This dynamic is accentuated through functionalization for tourism, which provokes the substitution of residents with a new floating population. This double gentrification has also been called “gentrification 2.0” [

39]. Along with this arrives a “non-community” of temporary travelers who neither work nor participate in neighborhood daily life [

40]. The consumer habits of these new occupants have a distinct tourist profile. This demand “turistifies” the neighborhood and changes the commercial landscape, which takes on the function of acting as a “showcase for tourists” while setting aside the needs of permanent residents.

In the case of Barcelona, this gentrification dynamic is reinforced by the emergence of “Airbnbification”, which adds pressure by means of a new concept of rental housing that is mostly temporary and aimed at tourists. This boom in the rental of temporary housing in coastal tourist areas and in emblematic cities such as Barcelona is fueled by young people with a digital profile and who are accustomed to low-cost travel and to seeking accommodation opportunities outside the usual hotel channels [

16,

17,

18,

22]. At the same time, the inhabitants of the neighborhoods take advantage of the opportunities to put their home or simply a room on the market for temporary rental. This form of renting to tourists has the objective of gaining income to complement the high rents or mortgage payments, or simply to increase the profitability of one’s home. The result is a high demand for rental housing that is being promoted by the Airbnb style of accommodation. The chronic nature of the phenomenon is favored by the limited role of public administrations in the face of the real estate market’s speculative drive.

The resident population has organized itself into social movements to demand that the local administration regulate and control the legalization of tourist rental housing while also curbing the aggressive policies of real estate speculation. Other Spanish cities have experienced the same phenomenon; for example Bilbao, which stands out on tourist maps because of the Guggenheim Museum megaproject; Palma de Mallorca, whose foreign population has increased continuously in comparison to the resident population; Valencia, which heavily promotes its sports mega-events; and Santa Cruz de Tenerife, with its tropical paradise of sun and beach throughout the year. The process is, therefore, widespread among Spanish cities that specialize in tourism. The pressure and demand for tourist accommodation have raised rental prices and put a strain on the economic power of residents, although local reactions suffer a division of opinion. On the one hand, tourists generate benefits and boost the economy of the city, while on the other they cause serious problems by increasing the price of housing for residents.

4. Social Movements, the Assembly of Neighborhoods for Sustainable Tourism (ABTS)

Henri Lefebvre [

41] anticipated that resistance to urban mutations would arise through the expression of collective power against privatization and commodification in capitalist societies. The principal demand is democratic management of the city government, of production, and the use of surplus value, to create social cohesion and live together with dignity [

42]. Resistance to the appropriation of common goods expresses itself through mobilization against the hegemony of the market and capital [

43,

44,

45]. The resident society in the affected cities has reacted since the beginning of the crisis by demanding solutions to the problem of evictions, the need for decent housing, and more affordable, fair rentals. In the case of Barcelona, an association has been created (the Sindicat de Llogaters, i.e., the Tenants’ Union) with the aim of presenting itself as a representative to the administration and demanding measures to alleviate the problems generated by tourist pressure. Because of these mobilizations, the problematic nature of offering tourist accommodation has entered the political agenda and public debate in cities like Madrid, Palma, Valencia and Barcelona.

In Spain, the residential use of housing is under pressure and has been displaced by the entrenched formula of investment in housing as a means of speculation, a situation in which residences are currently being commercialized as tourist accommodation. With the crisis and the globalization of the real estate market, the appropriation of the income obtained from housing has been transferred to financial institutions. In this context, small owners are also attracted by the greater benefits implied by the enhanced value of adding their real estate to the tourist rental market as compensatory income in the face of the crisis [

46].

The rental of homes for tourist use is considered good business that generates capital gains and attracts investors and speculators, in some cases accumulating properties and creating “pseudo-companies” for tourist rental that evade tax oversight. For the most part, these businesses are of an illegal nature and hidden behind supposedly non-profit exchanges and marketed through home-sharing platforms that benefit from these businesses but do not take charge of verifying their legality. This would be the case of the well-known Homeaway and Airbnb, of which the latter lists more than 3 million homes spread over 191 countries [

47].

Spanish regulations have been relaxed to deregulate the tourist rental of homes in Spain. There has been a social reaction from residents of cities that are in the process of touristification, such as Barcelona, Palma (Mallorca) and Madrid; specifically, they are manifesting social resistance to the marketing models of these platforms as well as to the development policies of their cities and the tourism sector. The daily life of the local population has been especially affected by the increase in housing prices in their neighborhoods along with the proliferation of tourist housing. The increase in tourist pressure displaces local residents, promotes changes in local businesses and daily public space, and creates or even colonizes outdoor cafés and public thoroughfares that become spaces for tourist use [

43].

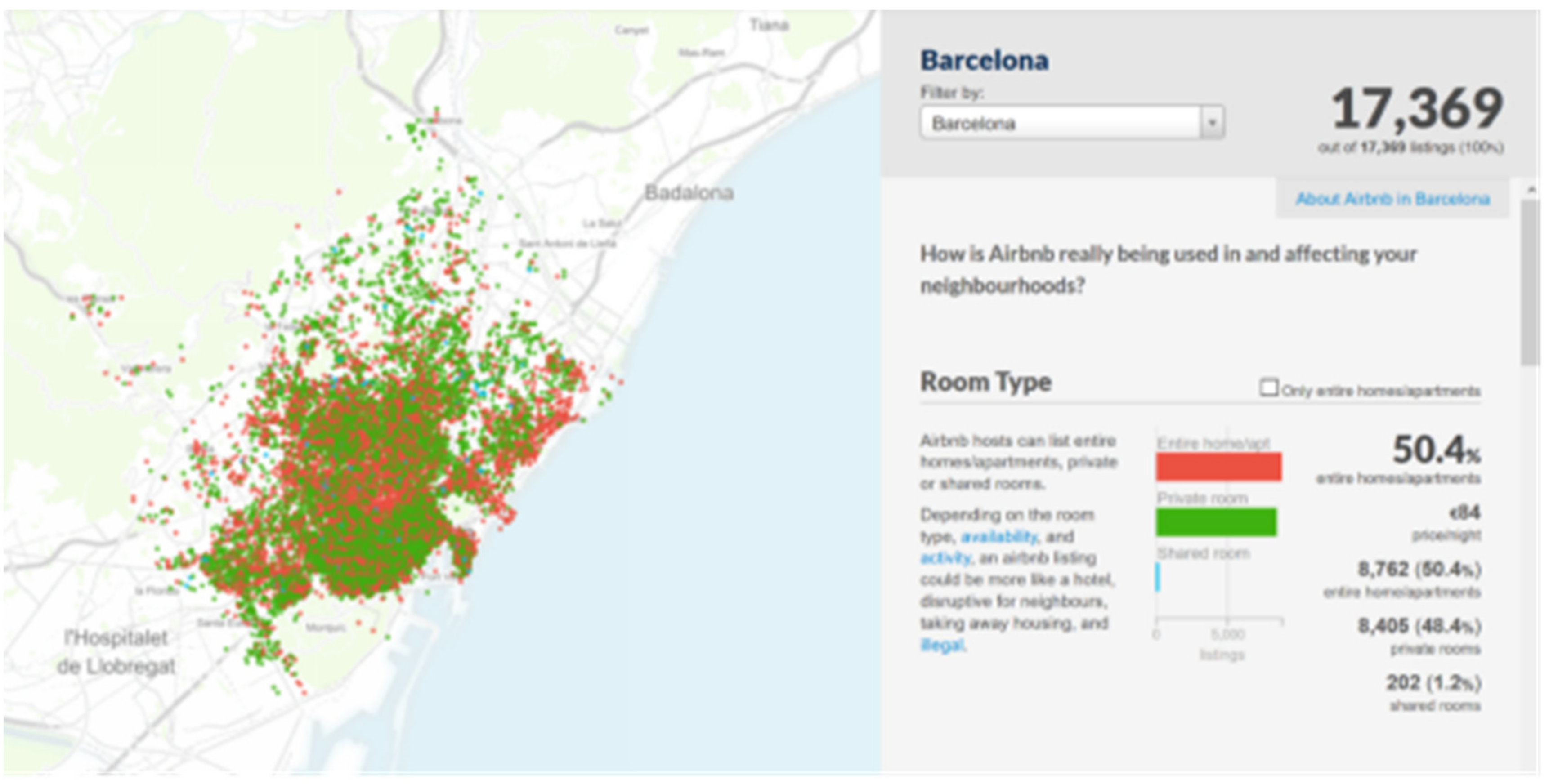

According to data from the Census of Tourist Accommodation Establishments in Barcelona, in April 2017 there were 10,544 establishments registered with a municipal file number, offering 149,058 places of accommodation, of which 58,951 corresponded to HUTs with a license [

48]. This is much lower than the actual figure, if the current non-legalized rentals are taken into account. Thus, according to Inside Airbnb data, the platform offers 17,369 tourist homes. Of these, 49.6% are rooms rented within an inhabited dwelling (in what could be considered a collaborative economy), but the remaining 50.4% are fully rented dwellings for tourist use [

49] (

Figure 2).

By 2015, this situation led to reactions by citizens in certain neighborhoods of the city center, such as Barceloneta, which has been especially affected by gentrification processes, real estate speculation, rent increases and an intensification of eviction practices for residents. This social resistance has been increasing over recent years and in November 2015 resulted in the creation of the Neighborhood Assembly for Sustainable Tourism (ABTS, by its Spanish acronym), promoted by citizens and aimed at demanding a decrease in tourism, redistributing the benefits generated by the sector (14% of GDP according to Turisme de Barcelona) and promoting economic alternatives. The appearance of the ABTS was defined as “… the people’s counterweight to help combat Barcelona’s hotel lobby” [

51]. The citizens sought to rethink the neoliberal tourism model of the city, to delve into the moratorium on hotels that was in force, to audit the public-private bodies related to tourism, and to shield public space from the city’s touristification process. With these same objectives, the First Neighborhood Forum on Tourism was held in July 2016. Its motto was “La ciutat es per viure-hi, no per viure’n” (“the city is for living in, not for living off of”), and the debate was raised on three axes of special concern in the city: the economic model of tourism, the management of ports and cruises, and alternative uses for housing and public spaces [

52].

The results of the surveys carried out by the Barcelona City Council on a sample of the population residing in Barcelona show that 86.7% of respondents consider tourism to be beneficial, reaching 92.9% in the less touristic districts. In parallel, 62% of the residents consulted for the present work consider that the tourism sector is important for the economy of the city, and 38% consider it important for cultural aspects that enrich city life. However, in parallel, 48.9% of respondents perceive the city as having reached its capacity limit for accommodating more tourists, and 64.6% believe that “the current volume of tourists received by the city is sufficient” [

53]. According to the data collected in our opinion pool, 54% affirm that the current nature of tourism in the city is characterized by uncivil behavior and 62% say that the tourist activity is not sustainable. In spite of everything, 85% of the residents in the affected areas believe that it is possible to find alternatives to improve the current situation. Of the solutions proposed, 27% are for reducing tourist housing, 46% for improving the City of Barcelona’s organization and planning of the sector, and 27% for gaining the cooperation of tourists and changing their consumer habits in the city.

This perception aims for a change of viewpoint regarding the unconditional benefits of tourism in earlier phases. The interventions of the ABTS and the various social platforms have focused on reports of illegal activities related to the tourism sector. They have participated in the governance process that the City Council launched for the development of the Strategic Tourism 2020 Plan, which favors a decrease in tourism and reducing overcrowding of the city.

5. Public Housing and Tourism Policies: The Special Urban Plan for Tourist Accommodation (PEUAT) in Barcelona

The international expansion of tourist housing accommodation and its contribution to the “rent price rise” have already led to some cases of municipal regulation, among other measures such as housing vouchers and the public offer of housing [

54]. Since 2015, some municipal councils in large cities have begun to use specific regulations for regulating economic activity that allows sharing a home with travelers. This is the case in several European cities such as Amsterdam (the first to reach an agreement with Airbnb), Paris, London, and Milan; in Canadian cities like Toronto and Vancouver; and in the United States, specifically New York and San Francisco, the birthplace of Airbnb [

55]. The measures taken by local governments are diverse: they limit the time for tourist rental, collect the tourist tax directly, or limit the buying-up of tourist rental homes with programs like “one host, one home” in San Francisco and New York. In the case of Berlin, the decision was drastic and the local government decided to ban tourist accommodation with the support of a court ruling [

56].

More recently, the City of Toronto has toughened legislation against short-stay leases following the appearance of so-called “ghost hotels”, which have been denounced by the association called Fairbnb with the support of affected neighborhood communities. These establishments appeared in 2016, when investors began to buy up homes, took them off the residential market and turned them into hotels on the black market, which are called “gray market hotels” and are offered through platforms such as Airbnb.

Other examples of regulations promote the collaborative rental economy through sharing residences. For example, the local government of Vancouver protects affordable housing. Its new rules, which came into force in 2018, entail:

Rules to allow short-term sharing of legal and registered houses only in homes that are actually the primary residence of the landlord.

The law will require that those sharing the home demonstrate that this is their primary residence.

The opening up of Airbnb data and other platforms to the City Council in order to reinforce additional laws and grant access licenses to other short-stay rental platforms.

Protection and other elements to prevent owners from converting second subsidized residences into units for “ghost hotels” [

57].

In Spain, measures have also been taken to alleviate the effects of relaxing laws on tourist accommodation rental. The Ministry of Finance has legislated the “obligation to report granting the use of a home for tourism purposes” (Royal Decree 1070/2017). As of July 2018, the Spanish Tax Agency will activate this new measure for controlling economic activity and the tax obligations of intermediary platforms, which are misnamed as collaborative, demanding that tourist rental housing platforms (Airbnb, HomeAway, Niumba, Wimdu, etc.) report information on their clients who advertise tourist rentals [

58].

The modification of Law 29/1994 on Urban Leases delegates the authority of regulating tourist accommodation in homes to the Autonomous Communities. Consequently, each Autonomous Parliament has legislated in a way that either embraces or rejects this business. In the Balearic Islands, the legislation includes an eloquent yet restrictive definition that runs counter to the primary model of this business: it is exclusive to natural persons who are owners of a home that is their primary dwelling and may be rented to tourists for a maximum period of 60 days per year. In Catalonia, the laws on tourist rental housing were already relaxed prior to the modification of the state law through Decree 159/2012 on tourist accommodation establishments and housing for tourist use. In this context, the Barcelona City Council has enacted regulation through instruments for urban and tourism planning as well as by using some municipal social housing initiatives.

In this last sense, the City of Barcelona devoted a great deal of effort throughout 2017 to purchasing complete buildings to avoid residential evictions and real estate speculation by investment funds. Until the end of 2017, the City Council chaired by Mayor Ada Colau (Barcelona en Comú) has committed, on an exceptional basis, to the acquisition of more than 5 buildings in order to deal with the speculation of the aforementioned investment funds and avoid the expulsion of the tenants [

59]. On the other hand, Barcelona City Council has carried out a census of the city’s empty flats. This count shows that 4% of all homes in the city are in disuse. The objective of Barcelona City Council is to contact the owners and offer them the possibility of incorporating their homes into the city’s rental market by granting guarantees on rent payment, facilities and benefits for renovating the dwellings [

60].

The previous government had already launched in 2010 a Strategic Tourism Plan for the city until 2015, in response to the social reaction against the pressure generated by tourism activities. As of 2013, district tourism plans were included in order to pursue a territorial decentralization of tourism activity. However, the internal dynamics of the sector and its relationships with the citizens did not improve. It is estimated that to date the City Council has granted 9606 licenses for tourist flats throughout the city [

61].

In 2015, before finalizing the Strategic Plan, it was necessary to promote a participatory process as a governmental measure in the city’s tourism model. At that time, the social resistance was unsustainable and an evaluation of the Action Program of the Strategic Plan 2010–2015 found that the majority had failed to fulfill the agreed measures. In general, 50% of development was not achieved in any of the proposed programs (15 in total), with governance having the lowest degree of development at below 25%. The plan served to confirm the great challenge of fitting tourism into urban areas such as Barcelona and the need for transversal measures with programs and actions in key areas such as neighborhoods and districts, sustainability and governing tourism. Although tourism in that period became one of the “star” topics in the media and a concern of the local population, the Strategic Plan itself had neither visibility nor presence in the media, and nor was there any consideration of their proposals by the social agents involved.

The measure that had the widest impact was the “moratorium” on licenses for tourist apartments, which was imposed in October 2014. This moratorium was extended in 2015 by the new municipal group Barcelona in Comú, which paralyzed the granting of licenses as a preliminary step in drawing up a special regulation plan for tourist accommodations. Although it could initially seem to be a restrictive measure, it had the support of the hotel business sector, who saw in it advantages in terms of exclusivity and monopoly—which appealed to them, given the sector’s extreme situation in the city. However, when in July 2016 its validity was extended until the definitive implementation of the special regulation plan, the hotel business sector saw the measure as a threat to its possibilities for growth and speculation in the tourism real estate sector. In this sense, it was made evident that efforts to control growth and downturns [

62] are not free of contradictions. This could favor gentrification, the monopoly of rents by both property owners and establishment operators, and the competitiveness of the destination [

7,

38,

46].

In January 2017, the first Special Urban Plan for Tourist Accommodation (PEUAT by its Spanish acronym) [

63], was approved with the aim of making tourist accommodation in the city compatible with a sustainable urban model based on guaranteeing fundamental rights and improving the quality of life for neighbours [

64]. As it came into effect, the existing moratorium ended. The PEUAT is pioneering in its scope, as it regulates the urban planning and management criteria for tourist accommodation in the city of Barcelona within the framework of the Urban Planning Law of Catalonia (Legislative Decree 1/2010). This legislation regulates the introduction of tourist accommodation establishments, including youth hostels, collective residences with temporary accommodation and HUTs. The HUTs are the most controversial aspect, as zero growth has been established for them throughout the city, although this remains a far cry from the decrease that has been demanded by social movements.

According to the Ecology, Urban Planning and Mobility Area for the Barcelona City Council, the purpose of the PEUAT is to improve the quality of life for citizens in the following ways:

Alleviating tourist pressure in different areas of the city.

Responding to public concerns regarding the growth of tourism, particularly the increase in tourist accommodation.

Seeking urban balance, preserving the quality of public spaces, and diversification to make tourism sustainable with other economic activities in the city.

Guaranteeing a city with morphological diversity in the urban fabric, depending on the characteristics of the urban area and the necessary conditions for accessibility.

Guaranteeing the right to housing, rest, privacy, the well-being of the neighborhood, spatial quality, sustainable mobility, and a healthy environment.

Based on the strategic diagnosis prepared in 2016, the PEUAT was configured as an urban planning instrument that distinguishes four zones with specific regulations (

Figure 3). Each of them is characterized by: the distribution of accommodation in the territory; the ratio between the number of tourist dwellings offered and the resident population; the relationship and conditions in which certain uses are allowed; the impact of activities on public spaces; and the presence of tourist attractions [

63].

The innovation lies mainly in the regulation of the HUTs by establishing zero growth throughout the city to avoid an excessive concentration of them and ensure a balanced territorial distribution. Thus, it is stipulated that “when a HUT ceases its activity in a congested area, a new license will be permitted in uncongested areas or the accommodation will be regrouped the area of maintenance or growth”.

Thus, Zone 1 is considered a zone of negative growth, meaning it allows neither setting up any type of tourist establishments nor any increase in the number of places at any existing establishments. It includes complete districts such as Ciutat Vella, Poble Sec, Vila Olimpica, Poblenou, Eixample, and Vila de Gràcia, as well as neighborhoods such as Hostafranch and Sant Antoni. These areas have the highest concentration of establishments (more than 60% of the city’s supply) and in some cases, such as the Gothic Quarter, the average visitor population to them reaches 69% with regards to residents. This special measure aims to achieve zero growth by limiting some areas like Ciutat Vella to the specific set of rules regarding HUTs, namely by regrouping places for tourists into an entire building and possibly relocating any possible reduced spaces to Zone 3, in accordance with the specific conditions of that zone.

Zone 2 is characterized by maintaining the number of places and current establishments by prohibiting these existing ones from expanding. It includes areas of Sants, Les Corts, Diagonal, Vila de Gràcia, Baix Guinardó, Sagrada Família, Fort Pienc, Llacuna and Diagonal Mar, which account for an average of 11% of the visitor population compared to residents. When a reduction occurs in Zone 2, it will be possible to open a new establishment in Zone 3 under the conditions determined for that zone. In Zone 3, setting up new establishments and expanding on existing ones is allowed, provided that the growth is contained. This is to be achieved by not exceeding the maximum density of places, which is determined by the morphological capacity of the area and the current degree of tourist accommodation that is offered. It affects a much wider area of the city and includes the areas of Les Corts, Sarrià, Vallcarca, Horta, El Guinardó, La Sagrera, La Verneda, Nou Barris, and others. Zone 4 includes other areas of the city with specific regulations because they are considered three major areas of transformation: the Marina del Prat Vermell, Sagrera and the northern area of 22@, all of them with very different territorial characteristics in terms of building density, uses and development. In these areas, establishing new HUTs is not allowed.

In addition to the 4 specified zones, the PEUAT contemplates two more action points with their own characteristics. On the one hand, in the Areas of Specific Treatment (ATE, by its Spanish initials), limits have been placed on setting up new establishments with additional conditions because of their urban morphology and the predominating uses taking place there. This mainly includes the old quarters of Sants, Les Corts, Sarrià, Horta, Sant Andreu, Clot-Camp de l’Arpa, Farró, Sant Ramon Nonat and Vilapiscina. On the other hand, certain conditions must be followed for establishments located along the main axes of the city, such as Ronda del Mig, Meridiana, Via Augusta, Diagonal, Gran Via, Av. Josep Tarradellas and Tarragona. In this way the city imposes a linear density condition of 150 m between establishments, which is linked to the radial distances they generate across their immediate surroundings.

Once the PEAUT came into effect at the end of March 2017, the current 2020 Strategic Tourism Plan [

58] also came into force with an action plan based on 10 programs, 30 action points and close to 100 specific measures. The new plan is presented as a collective strategy for achieving urban balance through the planning of tourist accommodation. Likewise, it is a commitment to sustainability and is based on a higher level of governance through the participation of all the stakeholders involved. The 30 action points are aimed at strengthening public leadership in the governance of tourism in order to serve the general interests of the city by sharing strategies with a wide variety of agents and seeking to reconcile tourism with the everyday life of the city. At the same time, it aims to improve the social return from tourism activity by activating its multiplier effects in order to develop other economic sectors (2020 Strategic Tourism Plan) [

65]. As such, elaborating the plan has involved multiple parties from civic life.

Although, both the PEUAT and the Strategic Tourism Plan have attempted to be the result of participative governance, its short trajectory has already seen lines of debate and tensions arise from among the different groups involved. Governance has tended toward reducing state influence by sharing the city government with private actors, a situation in which the most powerful continue to exert control and build consensus to maintain its hegemonic class [

66]. This instrumental political use legitimizes growth as a form of social cohesion for its virtuous cycle of creating wealth, capital gains, jobs, etc. [

67]. Thus, both the hotel business sector and citizens’ associations (ABTS among others) have already expressed their non-conformity, each in their respective sphere of activity. The Gremi d’Hotelers, the hoteliers’ trade association, has filed a judiciary appeal against the PEUAT for them to cease, and they demand the elimination of restrictions imposed on the growth of tourist accommodation in the city. For its part, the ABTS acknowledges the need for the PEUAT as a containment process, although they consider it insufficient because it fails to combat the problem of tourist overcrowding, as it still allows the number of tourist accommodations to increase. For the ABTS, the PEUAT does not address the proposals for zero growth and the reduction in overcrowding that had been demanded.

6. Discussion

Speculative processes when trade in an asset at a price or price range strongly exceeds the asset’s intrinsic value are typical of financial capitalism. As they take shape, they allow for the highest profit rates to be reached by expanding the frontiers of business, adding products and demand segments, either for their usage value or for their exchange value. Urban entrepreneurship and city marketing promote the commodification for tourism of daily life in multifunctional cities, as is the case of Barcelona. The tourist attraction and financial capital is accentuated, paradoxically, by the public policies for controlling and containing urban growth as well as the accommodation supply. The results presented here contribute to explaining the escalating rental prices of homes in this city, which in turn serves as an indication of the increasing dispossession that arouses social indignation and citizen demands for the right to housing.

As we have seen, since 2015 housing rental prices in the city of Barcelona have increased more than 10% (per square meter), which means that 40% of the population of the city is now forced to allocate more than 40% of their income to housing, levels that confirm the existence of a new housing rent price rise. Despite the heavy burden of the growing tourism sector in Barcelona, the appearance of this “housing rent bubble” is not exclusively due to a real increase in the value of the properties, nor to the increase in demand for changes in habits of its population, nor to the limited existing supply. The policies of urban entrepreneurship and the marketing of the city that are typical of neoliberalism have also stimulated the attraction of the housing market. To the aforementioned factors we must add: the almost null presence of public rental housing; the increase in the floating residential population that lives temporarily in the city; the pressure on the purchase of housing by foreign investment capital with speculative intent; and, of course, the recent phenomenon of increasing the supply of housing for tourist use. In Barcelona, one third of current home purchases (more than 100 properties in December 2017) are realized with investment funds whose objective is to maximize profits by allocating them for tourism exploitation. All this leads to great economic pressure due to the increase in demand.

Thus, the gentrification processes experienced in the city of Barcelona since 2005 have been accentuated by tourism becoming functionalized as of 2015, which in turn has led to residents being substituted by a new floating population. This could be considered double gentrification that is reinforced by a new concept of housing rental that is temporary and touristic.

This situation has brought about a strong social reaction and reversal of direction for municipal corporations, in this case with the mayorship of the Barcelona en Comú party. The reactions have emerged from within two main areas: residents and the local administrations. On the one hand, the resident population is concerned for the first time about the growth of tourism, and they pressure the local administration by demanding action through regulation and enforcing the legality of tourist rental housing. They also demand that the brakes be put on the aggressive policies of real estate speculation. Thus, in 2015, the public reaction of certain neighborhoods in the city center resulted in the creation of the ABTS. On the other hand, also in 2015, the current government of the Barcelona City Council decided to maintain the existing “moratorium” measures until the development and entry into force of the Strategic Tourism Plan (2017–2020). The Department of Urban Planning and Housing purchased complete buildings throughout 2017 to avoid both the eviction of residents and real estate speculation by investment funds. In January 2017, the PEUAT was approved and was the first instrument with these characteristics for regulating at an urban and tourist level the introduction of tourist accommodation. Finally, in February 2018, the plenary session of the city council approved a motion promoted by social groups to allow for expanding the public rental housing stock. The local government representatives argue that the tools already developed reach the maximum limits of the legal framework within Spain and the EU.

These containment measures to alleviate the tourist and rent price rise (by putting unoccupied homes on the market that are in the hands of private individuals or banks, or by regulating the high flow of HUTs) have been the result of participatory governance. However, it is evident that these will not be definitive solutions. Are other planning and management options available?

The resident population and social movements such as ABTS admit the need for PEUAT, but three key points have been proposed for improvement in Barcelona: on the one hand, the city should be considered as a whole, and tourist growth should be avoided not just contained; the validity of the plan should be extended for carrying out long-term actions (beyond the 4 years that were originally planned); and the city should regulate the implementation of previously granted licenses in addition to those allowed by the PEUAT (approximately 23,000 places in four and a half years). On the other hand, they propose the creation of a citizen Monitoring Committee that exercises control over compliance with the PEUAT and the established inspection and sanction mechanisms.

Additionally, certain lines of action are called for, such as: reinforcing the system for inspections and sanctions; legislating reforms that withdraw business licenses according to a determined number of infractions; and withdrawing the decree from of the Generalitat that allows for the introduction of Bed and Breakfasts in the city of Barcelona. In the case of increasing supply of social rental housing, approval of the motion does not guarantee that it will be fulfilled, as it is subject to the political will of the working group on the city council.

In this way we can see that the smooth functioning of tourism in the city requires direct planning and governance, but they are not the ultimate solution. Although municipal policies have tackled the issue of housing in order to avoid homes being commodified for tourism, this continues to be one more element in the current drift toward neoliberalism that attracts capital and tourists while supplanting residential uses. In a resurgence of social movements, the public reaction has taken center stage as residents confront the segregation of the dispossessed social classes. In the face of the trending policies that appeal to growth as a solution, there have been proposed alternative scenarios which require political debate of a voluntary and optimistic nature to promote equity and favor the working class [

68].

7. Conclusions

Sustainable urban tourism should aim to face the increasing tourist functionality of the traditional city. Housing being used to accommodate tourists is one of the new frontiers of tourist business in these urban spaces. Marking the border of the residential and tourist use of the built environment can be a way to solve this issue, through tourist and urban planning and management. Notwithstanding this, accommodation capacity is one of the key variables to measure the sustainability of a territory. Sustainability can be achieved, in this sense, through the application of urban planning and management measures. Sustainability measures should be oriented to improve the living conditions of the local population, such as their need for housing, boost the profitability of private business, and additionally contribute to improve the quality of the tourist experience.

Answering our first research question, our results conclude that tourism is not only responsible for this housing price increase. Housing rental price rises are due to a combination of factors such as household debt and the increase in demand arising from changes in the habits of a population or currently scarce supply; public policies of urban entrepreneurialism and the marketing of the city; evictions; investment by speculative capital pressuring on housing purchases that has clear and selective speculative intentions; changes in tenancy; the almost null presence of public rental housing; the increase in the floating population temporarily residing in cities such as Barcelona and Madrid; and stakeholders of properties in Spanish localities who have either a direct or indirect interest in tourism and the recent increase in the supply of Housing Used for Tourism (HUT). We reach this conclusion by, first, offering an overview of the housing rental market evolution in Spain; and second, analyzing the explanatory factors for the rental housing prices increases, particularly in the case of Barcelona.

Our second research question was whether it is possible to develop local administration policies to palliate this conflict. Engagement in governance is even more relevant with so many stakeholders involved. Issues involved in sustainable urban tourism cannot be solved without radical transformations to come up with solutions. In order to reach answers to this question we have, first, analyzed the social movement reactions to overtourism in the city of Barcelona; and, second, we have evaluated the local policies of urban and tourism planning developed by Barcelona’s government.

Barcelona’s local government has implemented measures for controlling, planning and limiting abuses in rental prices and housing tourist use. These local policies struggle within a context of liberalization of the housing rental market, e.g., via national Spanish regulation. We have focused our analysis particularly in the Special Urban Plan for Tourist Accommodation (PEUAT). The PEUAT regulates the urban planning and management criteria for tourist accommodation in the city of Barcelona within the framework of the Urban Planning Law of Catalonia. PEUAT regulates, among others, the HUT (in its Catalan acronym of Habitatges d’Ús Turistic). Although the PEUAT and other local public policies—such as the Strategic Tourism Plan—have attempted to be the result of participative governance, their short trajectory has already seen lines of debate and tensions arise. Both the hotel business sector and citizens’ associations (ABTS, among others) have already expressed their non-conformity, each in their respective sphere of activity. The Gremi d’Hotelers, the hoteliers’ trade association, demands the elimination of restrictions imposed on the growth of tourist accommodation in the city. For its part, the ABTS acknowledges the need for the PEUAT as a containment process, although they consider it insufficient because it fails to combat the problem of tourist overcrowding as it still allows the number of tourist accommodations to increase. For the ABTS, the PEUAT does not address the proposals for zero growth and reduction in overcrowding that had been demanded.

The government of Barcelona argues that these regulatory tools are the most appropriate choice, within the restrictions and limitations that the liberalizing EU and Spanish framework impose. Further research should contribute to answering emerging questions following our investigation: are other planning and management policies available? Where should the regulatory and planning measures be oriented to favor the sustainability of the city’s tourism development?

Barcelona could become the model for learning how to face these challenges, although this would require political will and social involvement. Despite the limitations of a case study, Barcelona is pioneering the process of intensification of the tourist restructuring of the city, as well as the social movements responses and local government policies to solve or palliate this challenge.