Multi-Stakeholder and Multi-Level Interventions to Tackle Climate Change and Land Degradation: The Case of Iran

Abstract

1. Introduction

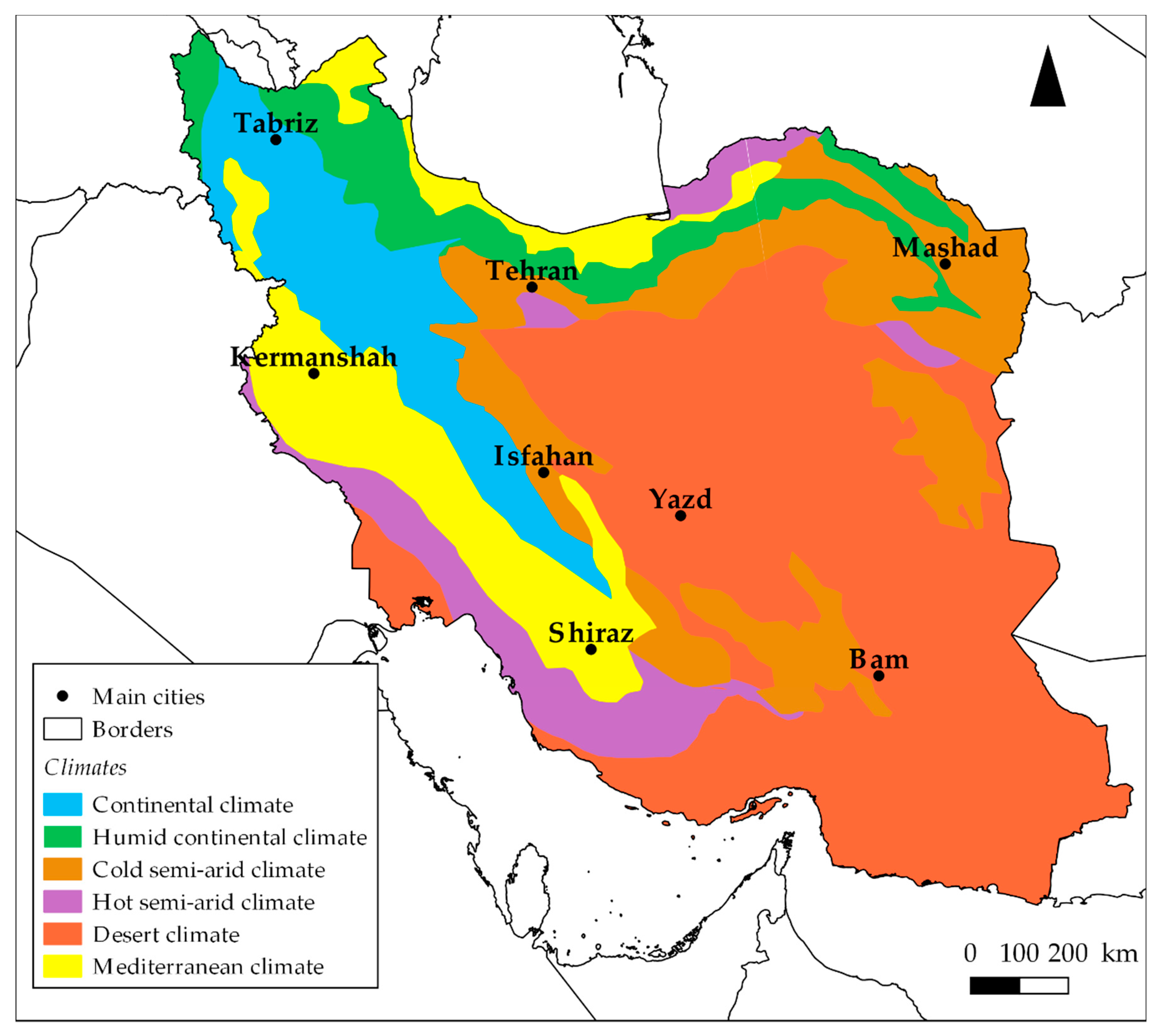

2. Background

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

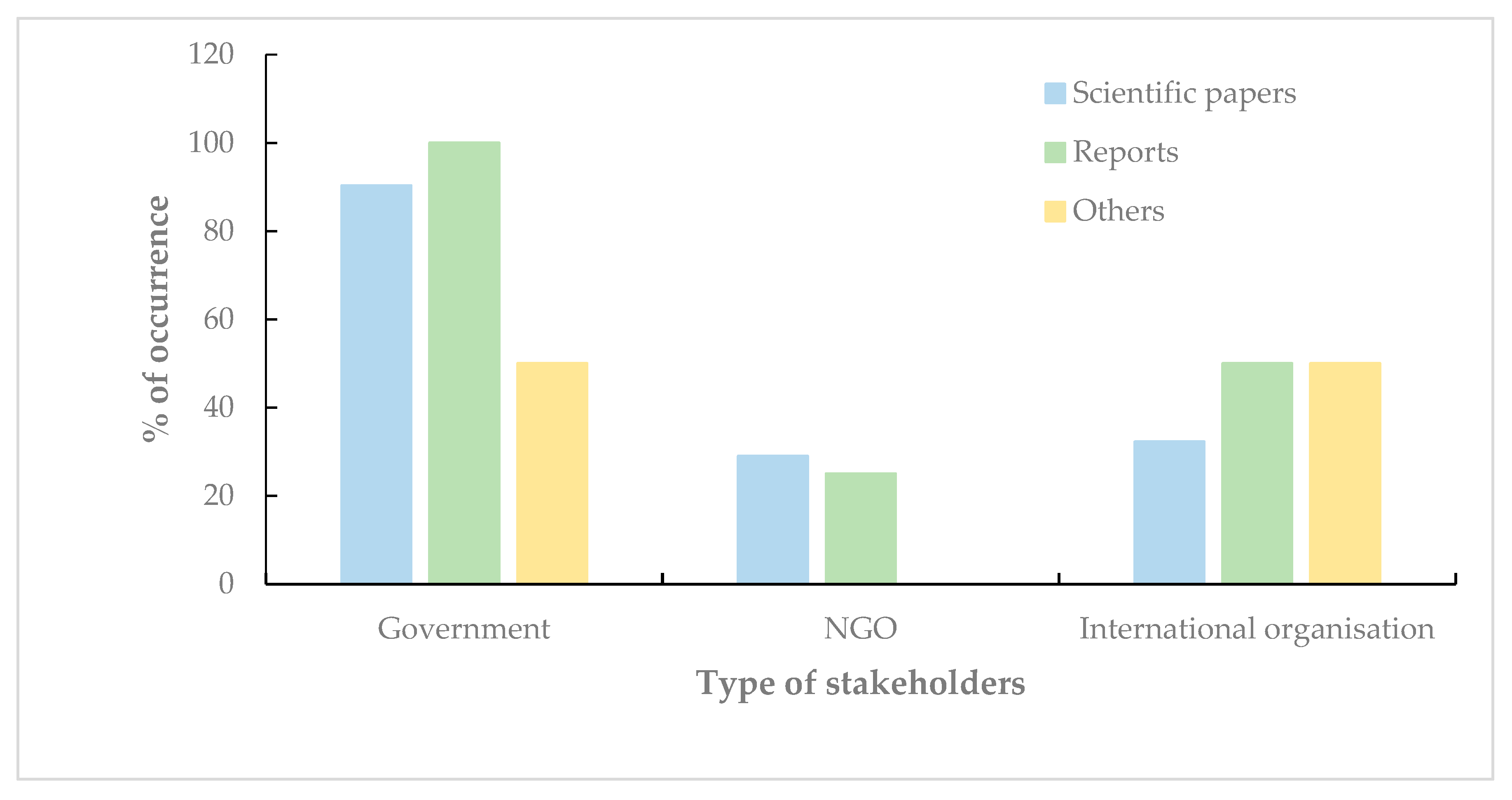

4.1. Who Are the Key Stakeholders Involved in Tackling Land Degradation and Climate Change and How are Relevant Information Flows and Communication Channels Established?

4.2. What Sort of Interventions Have Been Employed to Tackle Land Degradation and Climate Change from the 1950s to Date?

4.3. Identification of the Main Obstacles to Anti-Desertificaton and Climate Change Interventions in Iran

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hersperger, A.M.; Ioja, C.; Steiner, F.; Tudor, C.A. Comprehensive consideration of conflicts in the land-use planning process: A conceptual contribution. Carpath. J. Earth Environ. Sci. 2015, 10, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Stringer, L.C.; Dougill, A.J.; Thomas, A.D.; Spracklen, D.V.; Chesterman, S.; Ifejika-Speranza, C.; Rueff, H.; Riddell, M.; Williams, M.; Beedy, T.; et al. Challenges and opportunities in linking carbon sequestration, livelihoods and ecosystem service provision in drylands. Environ. Sci. Policy 2012, 19, 121–135. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1462901112000342 (accessed on 11 May 2013). [CrossRef]

- Okpara, U.T.; Stringer, L.C.; Dougill, A.J. Perspectives on contextual vulnerability in discourses of climate conflict. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2016, 7, 89–102. Available online: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/95752/ (accessed on 1 September 2017). [CrossRef]

- Barbier, E.B.; Hochard, J.P. Does Land Degradation Increase Poverty in Developing Countries? PLoS ONE 2016, 11, 1–12. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4864404/ (accessed on 12 February 2017). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costanza, R.; de Groot, R.; Sutton, P.; van der Ploeg, S.; Anderson, S.J.; Kubisewski, I.; Farber, S.; Kerry Turner, R. Changes in the global value of ecosystem services. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 26, 152–158. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959378014000685 (accessed on 19 March 2015). [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S.; Stringer, L.C. Land Degradation, Desertification and Climate Change: Anticipating, Assessing and Adapting to Future Change; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, K.; Nabatchi, T.; Balogh, S. An integrative framework for collaborative governance. J. Public Admin. Res. Theory 2012, 22, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice. J. Public Admin. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susskind, L.; Rumore, D.; Hulet, C.; Field, P. Managing Climate Risks in Coastal Communities: Strategies for Engagement, Readiness and Adaptation; Anthem Press: London, UK, 2015; 464p, ISBN 978-1-78308-486-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hossu, C.A.; Ioja, I.C.; Nita, M.R.; Hartel, T.; Badiu, D.L.; Hersperger, A.M. Need for a cross-sector approach in protected area management. Land Use Policy 2017, 69, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.R.; Deletic, A.; Wong, T.H.F. Interdisciplinarity: How to catalyse collaboration. Nat. News 2015, 525, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD). Land Matters for Climate: Reducing the Gap and Approaching the Target; The Change Town Initiative: Bonn, Germany, 2015; p. 24. ISBN 978-92-95043-04-6. [Google Scholar]

- Imperial, M.T. Using Collaboration as a Governance Strategy: Lessons from Six Watershed Management Programs. Adm. Soc. 2005, 37, 281–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossu, C.A.; Ioja, I.C.; Susskind, L.E.; Badiu, D.L.; Hersperger, A.M. Factors driving collaboration in natural resource conflict management: Evidence from Romania. Ambio 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noroozi, J.; Akhani, H.; Breckle, S.W. Biodiversity and phytogeography of the alpine flora of Iran. Biodivers. Conserv. 2008, 17, 493–521. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10531-007-9246-7 (accessed on 15 March 2014). [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, S.H.; Kelly, P.M. Developing credible vulnerability indicators for climate adaptation policy assessment. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2007, 12, 495–524. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11027-006-3460-6#citeas (accessed on 3 March 2015). [CrossRef]

- Kolahi, M.; Sakai, T.; Moriya, K.; Makhdoum, M.F. Challenges to the future development of Iran’s Protected Areas system. Environ. Manag. 2012, 50, 750–765. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00267-012-9895-5#citeas (accessed on 17 February 2018). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashrafi, K.; Shafiepour, M.; Ghasemi, L.; NajarAraabi, B. Prediction of climate change induced temperature rise in regional scale using neural network. Int. J. Environ. 2012, 6, 677–688. Available online: https://ijer.ut.ac.ir/article_538.html (accessed on 12 November 2017). [CrossRef]

- Ekhtesasi, M.; Abdinejad, G.H.; Kosari, M.; Niazi, Y.; Tabatabaiee, S.A. Changing of climatic parameters: Alarming sign of desertification in Yazd. Jangal-o-Marta 2006, 74, 7–10. (In Persian) [Google Scholar]

- Kousari, M.R.; Ekhtesasi, M.R.; Tazeh, M.; Saremi-Naeini, M.A.; Asadi-Zarch, M.A. An investigation of the Iranian climatic changes by considering the precipitation, temperature, and relative humidity parameters. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2011, 103, 321–335. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00704-010-0304-9#citeas (accessed on 17 October 2016). [CrossRef]

- Ahani, H.; Kherad, M.; Kousari, M.R.; van Roosmalen, L.; Aryanfar, R.; Hosseini, S.M. Nonparametric trend analysis of the aridity index for three large arid and semi-arid basins in Iran. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2013, 112, 553–564. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00704-012-0747-2 (accessed on 11 January 2018). [CrossRef]

- Marofi, S.; Sohrabi, M.M.; Mohammadi, K.; Sabziparvar, A.A.; Zare-Abyaneh, H. Investigation of meteorological extreme events over coastal regions of Iran. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2011, 103, 401–412. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00704-010-0298-3#citeas (accessed on 11 March 2017). [CrossRef]

- Raziei, T.; Daryabari, J.; Bordi, I.; Periera, L.S. Spatial patterns and temporal trends of precipitation in Iran. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2014, 115, 531–540. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00704-013-0919-8 (accessed on 17 May 2017). [CrossRef]

- Kousari, M.R.; Ahani, H.; Hakimelahi, H. An investigation of near surface wind speed trends in arid and semiarid regions of Iran. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2013, 114, 153–168. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00704-012-0811-y#citeas (accessed on 1 October 2017). [CrossRef]

- Amiraslani, F.; Dragovich, D. Combating desertification in Iran over the last 50 years: An overview of changing approaches. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 1–13. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20855149 (accessed on 14 March 2012). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NAP. National Action Programme to Combat Desertification and Mitigate the Effects of Drought of Islamic Republic of Iran; The Forest, Rangeland and Watershed Management Organization: Tehran, Iran, 2004; p. 48. ISBN 964-6931-69-3. (In Persian) [Google Scholar]

- Alijani, B.; O’Brien, J.; Yarnal, B. Spatial analysis of precipitation intensity and concentration in Iran. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2008, 94, 107–124. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00704-007-0344-y (accessed on 22 December 2017). [CrossRef]

- Karger, D.N.; Conrad, O.; Böhner, J.; Kawohl, T.; Kreft, H.; Soria-Auza, R.W.; Zimmermann, N.E.; Linder, H.P.; Kessler, M. Climatologies at high resolution for the earth’s land surface areas, 2017, Scientific Data 4, 170122. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/sdata2017122 (accessed on 12 June 2018).

- Karger, D.N.; Conrad, O.; Böhner, J.; Kawohl, T.; Kreft, H.; Soria-Auza, R.W.; Zimmermann, N.E.; Linder, H.P.; Kessler, M. Data from: Climatologies at high resolution for the earth’s land surface areas, 2017, Dryad Digital Repository. Available online: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.kd1d4 (accessed on 12 June 2018).

- Keshavarz, M.; Karami, E.; Zibaei, M. Adaptation of Iranian farmers to climate variability and change. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2014, 14, 1163–1174. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10113-013-0558-8#citeas (accessed on 16 October 2016). [CrossRef]

- Dinpashoh, Y.; Jhajharia, D.; Fakheri-Fard, A.; Singh, V.P.; Kahya, E. Trends in reference crop evapotranspiration over Iran. J. Hydrol. 2011, 399, 422–433. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022169411000461 (accessed on 11 November 2016). [CrossRef]

- Mullan, D. Soil erosion under the impacts of future climate change: Assessing the statistical significance of future changes and the potential on-site and off-site problems. Catena 2013, 109, 234–246. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0341816213000696 (accessed on 11 June 2014). [CrossRef]

- Amiraslani, F.; Dragovich, D. Preliminary assessment of economic dimensions and benefits of fifty years anti-desertification plans in Iran. In Proceedings of the UNCCD Second Scientific Conference, Bonn, Germany, 9–12 April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Available online: http://newsroom.uat.unfccc.int/media/495095/country-brief-iran.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2017).

- Makhdoum, M.F. Management of protected areas and conservation of biodiversity in Iran. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2008, 65, 563–585. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00207230802245898 (accessed on 9 December 2016). [CrossRef]

- Amiraslani, F.; Dragovich, D. Cross-sectoral and participatory approaches to combating desertification: The Iranian experience. Nat. Resour. Forum 2010, 34, 140–154. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1477-8947.2010.01299.x (accessed on 9 Januray 2010). [CrossRef]

- Tahbaz, M. Environmental Challenges in Today’s Iran. Iran. Stud. 2016, 49, 943–961. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00210862.2016.1241624?journalCode=cist20 (accessed on 10 May 2018). [CrossRef]

- Karimkoshteh, M.H.; Haghiri, M. Water-reform strategies in Iran’s agricultural sector. Perspect. Glob. Dev. Technol. 2004, 3, 327–346. Available online: http://booksandjournals.brillonline.com/content/journals/10.1163/1569150042442511 (accessed on 7 April 2015). [CrossRef]

- Strategic National Plan. Strategic National Plan for the Desert-Outlook 2025; Ministry of Agriculture: Tehran, Iran, 2008. (In Persian) [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (UN). United Nations Technical Mission on the Drought Situation in the Islamic Republic of Iran; UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2000; p. 35. [Google Scholar]

- Iran UNFCCC. Iran Second National Communication to UNFCCC; UNDP—Department of Environment: Iran, Tehran, 2010; 230p. [Google Scholar]

- Abdinejad, G. Desert and desertification in Iran: Policies, programmes and outcomes. Jangal-o-Marta 2007, 74, 23–26. Available online: http://www.frw.org.ir/00/En/ (accessed on 5 March 2015). (In Persian).

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Carbon Sequestration Project (CSP); United Nations: Tehran, Iran, 2011; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Haghani, G.; Hojati, M. The study of plant species diversification in biological measures for combating desertification. Jangal-o-Marta 2006, 14, 71–75. (In Persian) [Google Scholar]

- Hashemi, S.A.A.; Karimipour, H.; Jazi, H. Assessement of watershed management impact on erosion and sedimentation: Behvard watershed, Iran. Int. J. Dev. Res. 2015, 5, 4897–4904. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi, H.; Heshmati, G.; Pesarakli, M.; Naseri, R.H. Comparison of carbon sequestration in organs of Haloxylon species: Case study: South Salt Lake. In Proceedings of the Fourth National Conference on Pasture and Ange Management in Iran, Tehran, Iran, 21 December 2017; Publication of Research Institute of Forestsand Rangelands: Tehran, Iran, 2017. 346p. (In Persian). [Google Scholar]

- Manouchehri, G.R.; Mahmoodian, S.A. Environmental impacts of dams constructed in Iran. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2002, 18, 179–182. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/07900620220121738?journalCode=cijw20 (accessed on 16 May 2014). [CrossRef]

- Carle, J.; Vuorinen, P.; Del Lungo, A. Status and trends in global forest plantation development. For. Prod. J. 2002, 52, 1–13. Available online: http://www.fao.org/forestry/25856-0c773a78823b8b936c7f6c323919bd706.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2014).

- Moameni, A. Impact of Land Utilization Systems on Agricultural Productivity; Asian Productivity Organization: Tehran, Iran, 2003; 291p, ISBN 92-833-7010-4. [Google Scholar]

- Khosrokhavar, F.; Ghaneirad, M.; Toloo, G. Institutional problems of the emerging scientific community in Iran. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2007, 12, 171–200. Available online: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/097172180701200201 (accessed on 28 March 2015). [CrossRef]

- Koocheki, A.; Nasiri, M.; Kamali, G.A.; Shahandeh, H. Potential impacts of climate change on agroclimatic indicators in Iran. Arid Land Res. Manag. 2006, 2, 245–259. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15324980600705768 (accessed on 2 November 2016). [CrossRef]

- Fanni, Z. Cities and urbanization in Iran after the Islamic revolution. Cities 2006, 23, 407–411. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264275106000746 (accessed on 15 April 2018). [CrossRef]

- Karbasioun, M.; Mulder, M.; Biemans, H. Changes and Problems of Agricultural Development in Iran. World. J. Agric. Sci. 2008, 4, 759–769. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/37792164_Changes_and_Problems_of_Agricultural_Development_in_Iran (accessed on 18 December 2016).

- Abbaspour, M.; Faramarzi, M.; Seyed-Ghasemi, S.; Yang, H. Assessing the impact of climate change on water resources in Iran. Water Resour. Res. 2009, 45, 1–16. Available online: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2008WR007615/full (accessed on 12 December 2016). [CrossRef]

- Misra, M. Mobile pastoralists in Iran’s arid lands. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2009, 3, 357–370. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00207230902752512 (accessed on 30 June 2016). [CrossRef]

- Faramarzi, M.; Abbaspour, K.C.; Schulin, R.; Yang, H. Modelling blue and green water resources availability in Iran. Hydrol. Process. 2009, 23, 486–501. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/hyp.7160 (accessed on 10 November 2016). [CrossRef]

- Moradi, R.; Koocheki, A.; Nassiri-Mahallati, M. Adaptation of maize to climate change impacts in Iran. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2013, 19, 1223–1238. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11027-013-9470-2#citeas (accessed on 15 February 2018). [CrossRef]

- Amiraslani, F.; Dragovich, D. Forest management policies and oil wealth in Iran over the last century: A review. Nat. Resour. Forum 2013, 37, 167–176. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/1477-8947.12016 (accessed on 11 August 2013). [CrossRef]

- Javaherian, Z.; Maknoon, R.; Abbaspour, M.; Moharamnejad, M. Investigating the impacts of global environmental evolutions on long-term planning of natural resources in Iran. Int. J. Environ Res. 2013, 7, 561–568. Available online: https://ijer.ut.ac.ir/article_636.html (accessed on 3 April 2015). [CrossRef]

- Lerner, B. Available online: http://www.loc.gov/law/foreign-news/article/iran-law-to-protect-wetlands/ (accessed on 15 September 2017).

- Amiraslani, F.; Dragovich, D.; Caiserman, A. A long-term cost-benefit analysis of national anti-desertification plans in Iran. Desert 2018, 23, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Mendelsohn, R. The impact of climate change on agriculture in developing countries. J. Nat. Resour. Policy Res. 2009, 1, 5–19. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/19390450802495882 (accessed on 28 August 2014). [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, A. Community adaptation to climate change: Exploring drought and poverty traps in Gituamba location, Kenya. J. Nat. Resour. Policy Res. 2016, 5, 141–161. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/19390459.2013.811857?journalCode=rjnr20 (accessed on 20 June 2017). [CrossRef]

| Climatic Feature | Temporal Scale | Spatial Scale | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| A decline of 3.5 mm in annual mean rainfall | 25 years (1979–2004) | Yazd province (central Iran) | [19] |

| Significant reduction in summer rainfall | 55 years (1951–2005) | Country level | [20] |

| Decreasing trend in aridity index in southern basins | 50 years (1955–2005) | Arid and semi-arid basins | [21] |

| Changes in climatic extreme events (e.g., increase in warm nights, hot days, maximum wind speed) | 30 years (1977–2007) | All 12 southern and northern coastlines | [22] |

| Decreasing in spring and summer precipitation | 58 years (1951–2009) | Country level | [23] |

| Changing trends in near-surface wind speed (the frequency of the upward trends was more pronounced) | 30 years (1975–2005) | Arid and semi-arid areas | [24] |

| Stakeholder | Location | Year | Themes of Interviews | Context of Interviews |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farmers/local authorities | Several villages in South Khorasan province, East of Iran | 2012 | Participatory natural resources management | Carbon Sequestration Project |

| Farmers/local/national authorities | Several villages in Kermansh (West of Iran), Sistan-Baloochestan provinces (East of Iran), Yazd (Central Iran) provinces | 2013 | Local livelihood; income-generating activities in rural areas; integrated watershed management | Middle East and North Africa Regional Development for Integrated Sustainable Development (MENARID) Project |

| Farmers | Marvdasht (Fars province in Central Iran) | 2018 | Water management, agriculture | PhD research |

| In Persian | In English | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reports | Papers | Others | Reports | Papers | Others |

| [26,39] | [19,42,43,44] | [45,46] | [40,41] | [15,17,18,20,21,22,23,24,25,27,30,31,33,35,36,38,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59] | [34,60] |

| Organization and Date of Establishment | Activities |

|---|---|

| Ministry of Jehad-e-Agriculture (MoJA); since the early twentieth century |

|

| Forest, Rangeland, and Watershed Management Organization (FRWO); since the early twentieth century |

|

| Agricultural, Research, Education and Extension Organization (AREEO); 1974 |

|

| Department of Environment (DoE); 1970s |

|

| Iran Meteorological Organization; 1950s |

|

| Ministry of Energy (MoE); 1950s |

|

| Ministry of Science, Research and Technology; 1930s |

|

| International organizations |

|

| Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) (see text) |

|

| Others |

|

| Law/Plan | Remarks |

|---|---|

| Constitution Law | Article 50 of this law deals with the preservation of environment as a ‘public duty’. |

| Five-year National Development Plan | These plans generally comprise several budget chapters specifically addressing those environmental issues that must be tackled within the subsequent 5-year timeframe. |

| National Action Program to Combat Desertification [26] | Prepared through the National Secretariat of the Convention for Combating Desertification located within FRWO and submitted to the UNCCD in 2004, and has been revised several times since then. The core of this plan is to involve local people from designing to implementing stages to ensure the sustainability of projects that tackle land degradation [39]. |

| Comprehensive Natural Resources Management Law | Prepared and ratified over half of century ago (1950s) as the earliest contemporary policy document. The law considered a wise intervention and exploitation of rangelands and forests in the country. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amiraslani, F.; Caiserman, A. Multi-Stakeholder and Multi-Level Interventions to Tackle Climate Change and Land Degradation: The Case of Iran. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2000. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10062000

Amiraslani F, Caiserman A. Multi-Stakeholder and Multi-Level Interventions to Tackle Climate Change and Land Degradation: The Case of Iran. Sustainability. 2018; 10(6):2000. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10062000

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmiraslani, Farshad, and Arnaud Caiserman. 2018. "Multi-Stakeholder and Multi-Level Interventions to Tackle Climate Change and Land Degradation: The Case of Iran" Sustainability 10, no. 6: 2000. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10062000

APA StyleAmiraslani, F., & Caiserman, A. (2018). Multi-Stakeholder and Multi-Level Interventions to Tackle Climate Change and Land Degradation: The Case of Iran. Sustainability, 10(6), 2000. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10062000