Abstract

It is important to note that spiritual matter here is not about a religious, but a human centered view based on self-awareness, life purpose and community engagement. These three aspects of spirituality are the predominant perspective in the literature of organizational changes. These organizational changes are defining new paradigms for work relationships and impacting work environments. Some of these new paradigms are related to work motivation and job satisfaction, which are highly connected to organizational sustainability. Therefore, we choose to investigate workplace spirituality in order to move towards sustainability. In fact, there are already some reviews about workplace spirituality, and the most cited one organizes the topic in three dimensions: first, the inner life dimension that remains in self-centered matters such as identity and values; second, the sense of purpose dimension that refers to work significance perception; and lastly, the sense of community dimension that remains in connection and engagement. Okay, if we already have reviews about that, what is the point? In this review, we choose the predominant perspective on workplace spirituality to turn theoretical discussions into manageable human factors that are expressed by relationship needs at three levels: intrapersonal, interpersonal and institutional. With this new organization of the theme, we expect to support managers to perform actions focused on the type of relationship that is desired to be strengthened. From the review, we identify a total of twelve human factors organized by these three relationship levels, each one with four human factors. The main contribution of this study is a systematic review of workplace spirituality based on a human factor perspective.

1. Introduction

The technological evolution of work is being marked by a new wave of innovation and modernization in industry [1,2]. The changes observed in productive systems have solved several problems; however, they have opened space to debate new issues, such as job satisfaction and work life quality due mostly to a stressful workday focused on productivity [3,4].

From the worker point of view, maintaining productivity requires a self-motivation effort that goes beyond financial rewards [5,6]. In order to support employees in this motivational task, organizations are making efforts with different approaches [7,8]. One of these approaches has been discussed in the organizational changes literature as workplace spirituality, which was defined as “the recognition that employees have an inner life that nourishes and is nourished by meaningful work than takes place in the context of community” [9,10].

This review aimed to support these organizational efforts for sustainable operations by turning the recent theoretical discussion on workplace spirituality into manageable human factors expressed by relationship needs at three levels: intrapersonal, interpersonal and institutional.

2. Materials and Methods

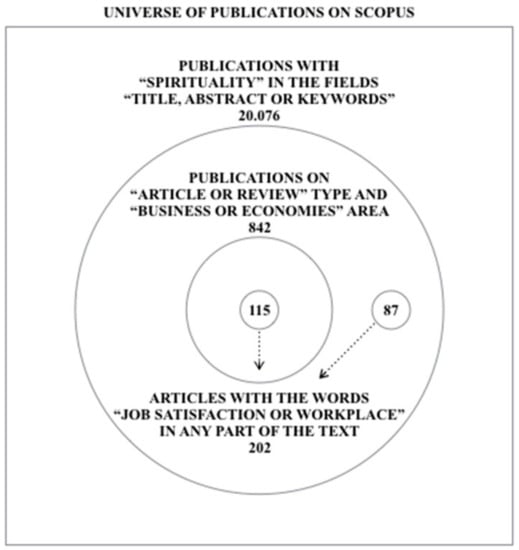

The research was marked by two major steps: first was the generation of spiritual human factors by a systematic literature review; after that, a theoretical model was proposed based on analyses of these human factors. The review strategy used was primarily generating a starting nucleus composed of an initial set of articles obtained from successive refinements on the Scopus database. We start from over twenty thousand publications about spirituality in general to two hundred potential articles for review. The first filter used was to limit results to “article or review” and the “business or economies” knowledge areas. At the end of this iteration, there were 842 articles. The second filter limited results to articles that have the words “workplace” and “job satisfaction” in some part of the article. With this iteration, we reached 115 articles. Finally, a third filter was used in order to retrieve some articles that have “workplace” and “job satisfaction” in their text, but were not classified in the “business or economies” areas. With this iteration, another 87 new articles were added. Thus, the starting nucleus was composed of 202 articles from the conjunction of these two samples (i.e., 115 + 87). This process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The starting nucleus for review; source: Scopus (accessed in November 2017).

The starting nucleus allowed the generation of the spiritual human factors. This generation process started from a selection of the most relevant articles to be reviewed. The selection was conducted by a title and abstract reading that elected 34 articles to be fully read. The criteria to select these 34 articles were full text free access and correlation to the research scope judge by the adherence of the article with the sample. These 34 articles were analyzed by coding techniques commonly applied to qualitative studies to transform texts, discourses or situations into useful data [11]. Fragments of these selected articles were highlighted, coded, categorized, grouped and decoded. All these steps are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The spiritual human factors’ generation; source: [11].

The criteria to identify text fragments that could be coded were previously parameterized by definitions or conclusions about spirituality. For decoding, the parameter used was the perspective of human necessity. The following coding methods were used:

- Holistic coding (attribute a code that conveys the central idea of a larger fragment): This was used first to extract the plurality of expressions of spiritual human factors;

- Descriptive coding (a noun that conveys the central idea of the highlighted text was alighted): This was used second to categorize the spiritual human factors. The categories used were based on the dimensions of spirituality proposed by Ashmos and Duchon [10]. Thirdly, this coding technique was used to group the spiritual human factors by similarity and then translate them into just one resulting factor that expressed the central idea of the grouped spiritual human factors.

3. Results

Workplace spirituality may refer to an individual’s attempts to live his/her own values more fully in the workplace or an organizational effort to support spiritual growth of their employees [12]. The literature had approached this topic through three dimensions: first, inner life or spiritual identity; second, sense of purpose or meaningful work; and third, sense of community or connection. In Table 1, the “X” marks the presence of these dimensions in previous works.

Table 1.

Workplace spiritual dimensions.

Even with the increase of contributed evidence, organizational efforts are still focused on a short locus of action based on leadership, culture and politics approaches [32]. As we are going to see in the results, we can conduct some alternative actions oriented toward specific factors to experience a linkage to ourselves, others and our environment. Despite this holistic view, it is naturally more common to find literature studies that focus on restricted aspects of workplace spirituality such as performance, commitment, well-being, self-esteem, turnover, decision making, and so on [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40].

The Twelve Spiritual Human Factors

The first step in the spiritual human factors’ generation process is presented in Table 2. In this table, all the human factors that could be extracted from the reviewed articles were registered based on textual fragments. In each fragment, a bold clipping is marked to represent the codification system. The highlighted words unfold into the spiritual human factors. Each highlighted section corresponds to one factor linked to the holistic coding by a numerical listing.

Table 2.

Spiritual human factors’ generation.

The second step of the spiritual human factors’ generation process refers to the categorization of these factors according to spiritual dimensions proposed by Ashmos and Duchon [10]. In Table 3, the spiritual human factors are presented according to their Table 2 listing number and grouped into categories by their affinity to workplace spiritual dimensions. In this table, we can see a balance in the total of factors in each category.

Table 3.

Categorization of spiritual dimensions by affinity.

The results of the third and last step of the review process are presented in Table 4. At this stage, the spiritual human factors were grouped according to their similarity and decoded in a resulting factor. At the end of this process, twelve spiritual factors were generated. For each spiritual dimension, four human factors were generated. In Table 4, the highlighted number between grouped factors represents the dominant factor that has more influence on factor description.

Table 4.

Grouping spiritual human factors by similarity.

4. Discussion

The result analyses come up with a pattern in the way that spiritual human factors can be organized. This pattern reveals that inside each spiritual dimension, the factors can be presented by the same structure based on three relationship levels: intrapersonal, interpersonal and institutional. The intrapersonal level represents a characteristic of internal orientation about the spiritual dimension, while the interpersonal level an external orientation and the institutional level an organizational orientation. This pattern is illustrated in Figure 3, where different circles represent the arrangement of spiritual factors based on these three relationship levels. In the center of this schema, the factor that expresses the main necessity related to the spiritual dimension is presented.

Figure 3.

Spiritual human factors’ arrangement pattern; source: analyses.

Based on this pattern, we analyzed the three spiritual dimensions: inner life, purpose and community. The dimension of inner life is comprised of a necessity to organize existential issues such as values, self-image and belonging. The attendance to this need leads to a state of serenity generated by harmonization of these existential questions. In Figure 4a, the spiritual factors in this dimension can be observed. The inner life factor refers to zeal for internal and personal issues, for example feelings, beliefs and values. Themes such as contemplation, humanity, nature, essence, existence, truth and self-knowledge are articulated to express this spiritual need. The values factor refers to personal guidelines for behaviors. This spiritual need represents a demand of alignment between organizational and personal values. The identity factor refers to self-awareness in its entirety. This spiritual need represents a demand for understanding your self-image. The belonging factor refers to capacity for empathy, that is to establish emotional connections. This spiritual need represents a demand for self-positioning to external issues.

Figure 4.

The twelve spiritual human factors by dimension: (a) Spiritual factors of Inner life dimension; (b) Spiritual Factors of purpose dimension; (c) Spiritual factors of community dimension; source: Table 2.

The dimension of purpose comprises a necessity to recognize meaning in daily actions. The attendance to this need leads to a state of serenity generated by finding justification and motivation for daily actions. In Figure 4b, the spiritual factors in this dimension can be observed. The purpose factor refer to your daily commitment with a legacy that integrates with all areas of your life. Themes such as future, quality, challenge, evolution, engagement, relevance and legacy are articulated to express this spiritual need. This spiritual need represents a demand for targeting daily actions towards a greater goal. The meaning factor refers to recognition of your contribution to others with the application of your best individual skills. This spiritual need represents a demand for usefulness and relevance at work recognition. The cohesion factor refers to a parallel evolution of professional and personal skills experienced at work. This spiritual need represents a demand for self-development and integration. The coherence factor refers to alignment between tasks’ difficulty level and skills. This spiritual need represents a demand for equilibrated challenges and tasks’ accomplishment.

The dimension of community is comprised of a necessity for reciprocity and respect for individuality. The attendance to this need leads to a state of serenity generated by sharing and acceptance of authenticity. In Figure 4c, the spiritual factors in this dimension can be observed. The community factor refers to respect for each individual’s basic beliefs and values. Themes such as communication, autonomy, respect, gentleness, attention, support and personality are articulated to express this spiritual need. This need represents a demand for the acceptance of your identity. The connection factor refers to empathy development through attention to personal issues in work relationships. This spiritual need represents a demand for maintaining integrity including your vulnerabilities. The climate factor refers to autonomy, communication and cooperation in professional relationships. This spiritual need represents a demand for lightness in work human interactions. The environment factor refers to freedom to express your personality in an integral way. This spiritual need represents a demand for expressing your individuality and authenticity.

It is important to note that this review adds a new framework to the existent literature of spirituality at work. If the researcher wants to access the major theoretical developments in this area, researchers can read great reviews such as Benefiel et al. [68] that explore the history and future research agenda for the domain definitions, constructs, frameworks and models.

5. Conclusions

This literature review shows that workplace spirituality considers three dimensions: inner life, sense of purpose and sense of community. The main contribution of this review was the generation of workplace spiritual human factors from the previous literature. The inner life dimension brings four human factors: identity, values, belonging and inner life. The purpose dimension brings another four factors: meaning, cohesion, coherence and purpose. The community dimension brings the last four factors: connection, climate, environment and community.

This perspective brings a practical approach to the issue by proposing that by meeting these spiritual needs, satisfaction and work life quality can be improved. The usage of this model can also contribute to individuals and organizations in the matter of understanding that their spiritual health needs attention, as well as their body and mind. Besides that, the model expresses a pattern in the organization of spiritual human factors. This pattern was interpreted in the model by relationship levels that refer to different manifestations of spiritual needs. These relationship levels were defined as intrapersonal, interpersonal and institutional. The intrapersonal level represents spirituality manifestation in a relationship with you, while the interpersonal level represents relationships with other people, and the institutional level represents relationships with organizations.

The main application of this finding was on workplace design or work design with the aim of achieving more sustainable relationships at work. For example, the spiritual human factors’ knowledge can be used in strategic planning to increase empathy in the process. The spiritual aspect on organizational changes can also support efforts to make work and its environment a better daily experience. At the team level, the attention to spiritual factors can add self-awareness, motivation and engagement. Finally, spirituality in the workplace is therefore about fostering opportunities for personal growth, opportunities to contribute significantly to society, as well as being more attentive to colleagues, bosses, subordinates and clients. It is about meeting your needs for inner life, purpose, and community, which means a more sustainable way to live, work and grow.

Author Contributions

R.L.F.B. and O.L.G.Q. designed the research. R.L.F.B. performed the review. R.L.F.B., F.T.F. and M.J.S.B. performed the analysis and discussions. R.L.F.B. wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Department of Production Engineering at Fluminense Federal University (UFF); Department of Management Systems at UFF; and the Coordination of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chawla, V. Workplace spirituality governance: Impact on customer orientation and salesperson performance. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2016, 31, 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathisen, G.E.; Brønnick, K.; Arntzen, K.J.; Bergh, L.I.V. Identifying and managing psychosocial risks during organizational restructuring: It’s what you do and how you do it. Saf. Sci. 2017, 100, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, T.K.; Kenigsberg, T.A.; Pana-Cryan, R. Employment arrangement, job stress, and health-related quality of life. Saf. Sci. 2017, 100, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noor, S.; Arif, S. Achieving job satisfaction VIA workplace spirituality: Pakistani doctors in focus. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. 2011, 19, 507–515. [Google Scholar]

- Poulsen, S.; Ipsen, C. In times of change: How distance managers can ensure employees’ wellbeing and organizational performance. Saf. Sci. 2017, 100, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altaf, A.; Awan, M.A. Moderating affect of workplace spirituality on the relationship of job overload and job satisfaction. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 104, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Kumar, S. Workplace spirituality as a moderator in relation between stress and health: An exploratory empirical assessment. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2014, 26, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goltz, S.M. Spiritual power: The internal, renewable social power source. J. Manag. Spirit. Relig. 2011, 8, 341–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, K.; Singh, J. Spirituality at workplace: A conceptual framework. Int. J. Appl. Bus. Econ. Res. 2016, 14, 5181–5189. [Google Scholar]

- Ashmos, D.P.; Duchon, D. Spirituality at work: A conceptualization and measure. J. Manag. Inq. 2000, 9, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.; Saldana, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Method Sourcebook, 3rd ed.; Editora Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Walt, F.; de Klerk, J.J. Workplace spirituality and job satisfaction. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2014, 26, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burack, E.H. Spirituality in the Workplace. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 1999, 12, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, L. Spiritual Leadership and Faith and Spirituality in the Workplace. In Handbook of Faith and Spirituality in the Workplace: Emerging Research and Practice; Neal, J., Ed.; Springer Science + Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 697–704. [Google Scholar]

- Giacalone, R.A.; Jurkiewicz, C.L. Toward a Science of Workplace Spirituality. In Handbook of Workplace Spirituality and Organizational Performance; Giacalone, R.A., Jurkiewicz, C.L., Eds.; M.G. Sharpe: Armonk, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Graber, D.R. Spirituality and Healthcare Organizations. J. Healthc. Manag. 2001, 46, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillory, W.A. The Living Organization: Spirituality in the Workplace; Innovations International: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, M.; Kumar, V.; Singh, M. Creating Satisfied Employees through Workplace Spirituality: A Study of the Private Insurance Sector in Punjab (India). J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 122, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakas, F. Spirituality and Performance in Organizations: A Literature Review. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 94, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinjerski, V. The Spirit at Work Scale: Developing and Validating a Measure of Individual Spirituality at Work. In Handbook of Faith and Spirituality in the Workplace: Emerging Research and Practic; Neal, J., Ed.; Springer Science: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 383–402. [Google Scholar]

- Kurth, K. Spiritually Renewing Ourselves at Work. In Handbook of Workplace Spirituality and Organizational Performance; Giacalone, R.A., Jurkiewicz, C.L., Eds.; M.G. Sharpe: Armonk, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 447–460. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, J.; Dhiman, S.; King, R. Spirituality in the Workplace: Developing an Integral Model and a Comprehensive Definition. J. Am. Acad. Bus. 2005, 7, 81–91. [Google Scholar]

- Milliman, J.; Czaplewski, A.J.; Ferguson, J. Workplace Spirituality and Employee Work Attitudes. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2003, 16, 426–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirvis, P.H. ‘Soul Work’ in Organizations. Organ. Sci. 1997, 8, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitroff, I.I.; Denton, E.A. A Study of Spirituality in the Workplace. Sloan Manag. Rev. 1999, 40, 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Naylor, T.H.; Willimon, W.H.; Osterberg, R. The Search for Meaning in the Workplace; Abington Press: Nashville, TN, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Neal, J. Work as Service to the Divine: Giving our Gifts Selflessly and with Joy. Am. Behav. Sci. 2000, 43, 1316–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neck, C.P.; Milliman, J.F. Thought Self-leadership. J. Manag. Psychol. 1994, 9, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J. Spirituality in the Workplace. CA Mag. 1999, 132, 41–42. [Google Scholar]

- Pawar, B.S. Individual Spirituality, Workplace Spirituality and Work Attitudes: An Empirical Test of Direct and Interaction Effects. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2009, 30, 759–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petchsawang, P.; Duchon, D. Workplace Spirituality, Meditation, and Work Performance. J. Manag. Spirit. Relig. 2012, 9, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, J.D.; Neck, C.P.; Krishnakumar, S. The what, why, and how of spirituality in the workplace revisited: A 14-year update and extension. J. Manag. Spirit. Relig. 2016, 13, 177–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman-Gani, A.M.; Hashim, J.; Ismail, Y. Establishing linkages between religiosity and spirituality on employee performance. Empl. Relat. 2013, 35, 360–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, V.; Guda, S. Individual spirituality at work and its relationship with job satisfaction, propensity to leave and job commitment: An exploratory study among sales professionals. J. Hum. Values 2010, 16, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejeda, M.J. Exploring the supportive effects of spiritual well-being on job satisfaction given adverse work conditions. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 131, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, B.A.; Dellert, J.C. Exploring nurses’ personal dignity, global self-esteem and work satisfaction. Nurs. Ethics 2016, 23, 384–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell-Ellis, R.S.; Jones, L.; Longstreth, M.; Neal, J. Spirit at work in faculty and staff organizational commitment. J. Manag. Spirit. Relig. 2015, 12, 156–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beehner, C.G.; Blackwell, M.J. The impact of workplace spirituality on food service worker turnover intention. J. Manag. Spirit. Relig. 2016, 13, 304–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, M.; Jackson, B. The influence of religion-based workplace spirituality on business leaders’ decision-making: An inter-faith study. J. Manag. Organ. 2006, 12, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, K. Congruence and clash of scientific and spiritual identities: Consequences for scientists, organizations, and organizational leadership. J. Manag. Spirit. Relig. 2007, 4, 187–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Omar, Z. Reducing deviant behavior through workplace spirituality and job satisfaction. Asian Soc. Sci. 2014, 10, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, I.F.; Cunha, R.C.; Martins, L.D.; Sá, A. Primary health care services: Workplace spirituality and organizational performance. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2014, 27, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad Marzabadi, E.; Niknafs, S. Organizational spirituality and its role in job stress of military staff. J. Mil. Med. 2014, 16, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Baran, B.E.; Shanock, L.R.; Miller, L.R. Advancing Organizational Support Theory into the Twenty-First Century World of Work. J. Bus. Psychol. 2009, 23, 123–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, M.P.; Rego, A.; D’oliveira, T. Organizational spiritualities: An ideology-based typology. Bus. Soc. 2006, 45, 211–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, J.L. Workplace spirituality and stress: Evidence from Mexico and US. Manag. Res. Rev. 2015, 38, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Klerk, J.J. Spirituality, meaning in life, and work wellness: A research agenda. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2005, 13, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doram, K.; Chadwick, W.; Bokovoy, J.; Profit, J.; Sexton, J.D.; Sexton, J.B. Got spirit? The spiritual climate scale, psychometric properties, benchmarking data and future directions. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duchon, D.; Plowman, D.A. Nurturing the spirit at work: Impact on work unit performance. Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 807–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazzawi, I.A.; Smith, Y.; Cao, Y. Faith and job satisfaction: Is religion a missing link? J. Organ. Cult. Commun. Confl. 2016, 20, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, P., Jr. Tattvabodha and the hierarchical necessity of Abraham Maslow. J. Manag. Spirit. Relig. 2016, 13, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurkiewicz, C.L.; Giacalone, R.A. A values framework for measuring the impact of workplace spirituality on organizational performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 49, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, V. ‘Visionaries... psychiatric wards are full of them’: Religious terms in management literature. Verbum Et Ecclesia 2017, 38, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinjerski, V.; Skrypnek, B.J. The promise of spirit at work. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2008, 34, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolodinsky, R.W.; Giacalone, R.A.; Jurkiewicz, C.L. Workplace values and outcomes: Exploring personal, organizational, and interactive workplace spirituality. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 81, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutcher, E.J.; Bragger, J.D.; Rodriguez-Srednicki, O.; Masco, J.L. The role of religiosity in stress, job attitudes, and organizational citizenship behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, A. Spirituality and job satisfaction among female Jewish Israeli hospital nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2010, 66, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, J.F. The spiritual worker: An examination of the ripple effect that enhances quality of life in- and outside the work environment. J. Manag. Dev. 2006, 25, 884–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschke, E.; Preziosi, R.; Harrington, W.J. How sales personnel view the relationship between job satisfaction and spirituality in the workplace. J. Organ. Cult. Commun. Confl. 2011, 15, 71–110. [Google Scholar]

- Mccormick, D.W. Spirituality and Management. J. Manag. Psychol. 1994, 9, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcguire, T. From emotions to spirituality: “spiritual labor” as the commodification, codification, and regulation of organizational members’ spirituality. Am. J. Men Health 2010, 4, 74–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryal, V.; Ramkumar, N. Ascertaining individual’s spiritual growth and their performance orientation. Purushartha J. 2016, 8, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ramnarain, C.; Parumasur, S.B. Assessing the effectiveness of financial compensation, promotional opportunities and workplace spirituality as employee motivational factors. Corp. Ownersh. Control 2015, 13, 1396–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, A.; Pina, E.; Cunha, M. Workplace spirituality and organizational commitment: An empirical study. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2008, 21, 53–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sani, A.; Soetjipto, B.E.; Maharani, V. The effect of spiritual leadership on workplace spirituality, job satisfaction and ihsan behaviour (a study on nurses of aisyiah Islamic hospital in Malang, Indonesia). Int. J. Appl. Bus. Econ. Res. 2016, 14, 7675–7688. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Walt, F.; de Klerk, J.J. Measuring spirituality in South Africa: Validation of instruments developed in the USA. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2014, 26, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Word, J. Engaging work as a calling: Examining the link between spirituality and job involvement. J. Manag. Spirit. Relig. 2012, 9, 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benefiel, M.; Fry, L.W.; Gleige, D. Spirituality and Religion in the Workplace: History, Theory, and Research. Psychol. Relig. Spirit. 2014, 6, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).