1. Introduction

Currently, a healthier lifestyle is being increasingly emphasized on a global scale, especially as special attention is given to increasing the amount of time dedicated to sports and physical activities. The relationship between sport and sustainability has been the focus of different approaches lately. Various documents adopted by the European Union (e.g., White Paper on Sport—2007 [

1] and How to Promote the Social Sustainability of Major Sports Events—2015, [

2]) had a specific focus on sport and sustainability relationship. This latest one also emphasized that “social aspects and components have been excluded from focus of public opinion, scientific research on sustainability and the legacy of sports events, and economic, environmental, as well as social dimensions should be taken into consideration and pursued. Sports events can provide various opportunities and deliver beneficial effects, for example, on social cohesion, participation in sport, individual skills development, and creation of specific know–how”.

These documents also underlined their outstanding significance, and various concepts/strategies drawn up by governments have taken a similar stand on these issues. A scientific report of the UCL Environmental Institute [

3] declared that the “sports sector already recognises that it can make a major contribution to social well-being through both personal development and the development of local communities. However, care needs to be taken to ensure that such benefits are spread in an equitable and long. Two main strands highlighted of social sustainability were public health and community cohesion”. In this brief report, based on numerous references, the authors emphasize that “sports can improve public health benefit, may have an impact on academic achievement, future employability, building skills and confidence, and these effects may last for several decades.” They also concluded that “with the appropriate planning and management, sporting activity can contribute to social inclusion and ensure the widespread access to sporting facilities across communities, including the most deprived communities.”

Global organizations, such as WWF [

4] in their recently-published report “Sustainability through Sport” deals with the topic of the relationship between sport and sustainability, claiming that “sports (events) are impacting nature and also impacted by it. Sports (events) have direct impacts, such as energy, waste, pollution, and among others use important habitats in competition and trainings. On the other hand, sports are threatened by heavy pollution, or climate changed induced extreme weather events. The loss of nature equals with the loss of sports experience.” They declared and emphasized trends with an objective to “clarify how sport’s (event) focus on environment is relevant for everyday participants and what they can do themselves, and take broader responsibility and advocate for green sports in public policy.” They also urged to raise awareness and exciting people through partnerships. We also interpret it as our knowledge on sports activity and the relationship between sports, the pursuing activity of people, and the environment, itself, should be better understood.

Even the media show interest toward sports issues regarding sustainability. The Guardian expresses [

5] that “linking the power of sport to sustainable living initiatives makes plenty of sense. Sport events and sporting affiliations contain many of the preconditions for promoting mass behaviour change (that is social sustainability)”. Another related article [

6] deals with sports and environmental sustainability, claiming that “various countries continue to search for new and innovative methods of reducing their carbon footprint”, and lately it became important that, at the organization of large-scale events, such as the Olympic Games, and at the establishment of sport-related infrastructures, or even at the sport club level, since, for example, “there is an increasing trend for sports stadia to be innovative in their ability to be sustainable”.

According to the results of a questionnaire survey conducted in November 2013 in 28 countries of the European Union and involving 27,919 respondents, 41% of the responding EU citizens participate in sports or perform some kind of physical activity at least once a week, while 59% are only rarely or never active [

7]. Compared to the 2009 survey, the results have not changed significantly, however, it is unfortunate that the proportion of those who never pursue any sports has risen from 39% to 42%. Generally speaking, a larger proportion of men do sports or perform some kind of physical activity than women (the most significant difference in this category was recorded in the age group of 15–24 year olds (men: 74%, women: 55%).

Compared to the results of the 2009 survey, the results in Hungary have improved among those who do sports and the proportion of people who do not pursue any kind of sports, decreased by 9%, but even so, 44% of Hungarian citizens do not play any regular sports at all. The ratio of those, who have never attended any live sports events is about 65% (between people aged 25–64), and compared to the EU-28 average we spend more of the total household sport budget on recreational and sporting services (Hungary, about 85%; EU-28, about 60%), and only about 10% on equipment for sport, camping, and open-air recreation [

8]. Just one additional indicator is the rise of interest on e-sports, e-sports are gaining higher importance, the total number of gamers, competitors and offline competition visitors is about 200,000, with four out of five participants being younger than 25, and one third are below 18 years of age [

9].

In Hungary, developing sport into an industry has become a fundamental interest and a noticeable approach in recent years. A so-called economic orientation can also be observed in the field of leisure time sports, which was made into law in Hungary in 2011, allowing the support of sport organizations and resulting in a number of infrastructural developments [

10].

The subject has attracted the attention of researchers and there have been multiple studies in recent years that analysed the various characteristics of sports and physical activities. According to the results of the emerging studies, considerable differences can be observed amongst countries within the European Union; in this regard, a decline along the north–south and west–east directions is present in terms of the frequency of sports activities [

11].

Other researchers have focused on the sporting habits of various groups within the population, and—among other factors—they pointed out the influencing role of age, gender, school qualification, and income status [

12,

13,

14].

However, most of the analyses examined the cause and motivation of sport-related activities. In this regard, analyses can be classified under different fields of science, especially sociology, psychology, and economics. The following chapter provides a brief overview of these fields of study.

2. Approaches Related to Sports and Physical Activities

2.1. Sociological/Societal Approach of Sports Involvement

From the second half of the 20th century, leisure time has been playing a greater role in the life of people, and their spending possibilities show a varied picture of leisure activities. Sporting activities are usually referred to as meaningful ways of spending leisure time. The data provided by the Hungarian Central Statistical Office and other representative sample based research enable us to define the details of sporting habits. For example, until 2012 between 30–40% of the total population pursued some kinds of sport. The activity level differs by gender (males are more active) and chances for pursuing sport changes depending on financial possibilities. Activity is also dependent on relationship with friends, and we may know more about the motivation behind the sporting activity.

Still, we observed that most fundamental sport-related questions remained unanswered and unlearned. We have some unclear, ambiguous conceptual questions and the most vital dilemma remained the nature of relationship between sport and the society itself, which seems to be a comprehensive category. It is obvious that the relationship between society and sport cannot be simplified purely by defining the number of people doing sports. Sport and the society have further common points of connection, including other exciting indicators, as well. The term regarded as “engagement” in the national and international professional literature may offer a more comprehensive view to the phenomenon examined. This term has already been applied in some fields and they also have experimental results. In the international literature ([

15] (p. 164), [

16] (p. 75)), the term “civic engagement” has been covered, which is in relationship with civic activity connected to civic movements and organizations. In these, civic engagement means that citizens work together for a commonwealth and social capital is a relative and enforceable trust based relationship, by which people and institutions access such resources as social services, volunteers, donations. Strictly speaking, civic engagement means the participation of citizens in social institutions so as to serve general social objectives. On the other hand, engagement does not only include participation. Gerő [

17] (p. 321) in his essay deals with the questions of measurement of the civic society together with its problems. He has drafted additional indicators besides the members, active members, and senior members, such as participants at events, in activities, the frequency of civic participation, number of civic organizations, details of voluntariness (this latest shows varied picture by diverse examinations), the number of employees, participation in actions (such as flash mob), donation habits, or the domestic income tax donation.

A similar problem in a different field raised the attention of the experts of domestic rural research, Kovách [

18] (p. 25), who has covered the issues of agricultural engagement in his academic doctoral thesis. The problem of engagement similarly appeared in the agricultural sphere, where the importance of the sphere is more often simplified by the decreasingly small number of employees, although employment is the sole social indicator of the connection between society and agriculture. His concepts and examinations have revealed that agricultural engagement may be understood in more than one way. For example, one indicator is the employment in the sphere, but further indicators may be drafted, such as land ownership, agricultural education, agricultural family relationship, or pursuing production for market or private consumption. The number of agricultural employment does not equate with agricultural engagement, and experimental results showed a multiplied engagement level compared to the number of employees. The examination of agricultural engagement lets us know that the social importance of the agriculture is not negligible: in 2005, 51.6% of the adult population in Hungary was agriculturally engaged, while only 194,000 people were employed in the sector [

19] (p. 45).

If we adopt these approaches, it is clear that, in the field of sport, we need to struggle with similar dilemmas. By accepting these approaches, it seems to be exciting to observe how society often considers this question in a simplified manner. The issues of the fields and strengths of sports engagement along with its improving possibilities may also offer challenges for the researcher. One additional indicator of sports engagement may be the number of employees of sports organizations, and a further indicator or category may also include those ones directly (participating in a sports event) or indirectly (watching sports on the TV) engaged, both may be independent from any personal sporting activity (do not have to pursue). Not only citizens, but also organizations, dealing with sports (gathering donations) may also reveal a different picture of engagement, which means it may be measured from different points. Sports engagement is possibly the most comprehensive category by which the relationship between the society and the sports sector may be identified, researching its different dimensions, variables, and depths may also contribute to the improvement of the role of sports in the life of the society.

2.2. Psychological Approach of Sports Involvement

Multiple researchers have already dealt with the analysis of the psychological motivation behind active and passive participation in sports. Sports involvement analyses of this perspective resulted in the emergence of a multidimensional model. Kerstetter and Kovich [

20] use the conceptual definition of involvement provided by Havitz and Dimanche [

21] (p. 184): “a psychological state of motivation, arousal, or interest between an individual and recreational activities, tourist destinations or related equipment at one point in time, characterized by the perceptions of the following elements: importance, pleasure value, sign value, risk probability and risk consequences.” Using this definition, involvement was operationalized as a multi-dimensional construct [

22].

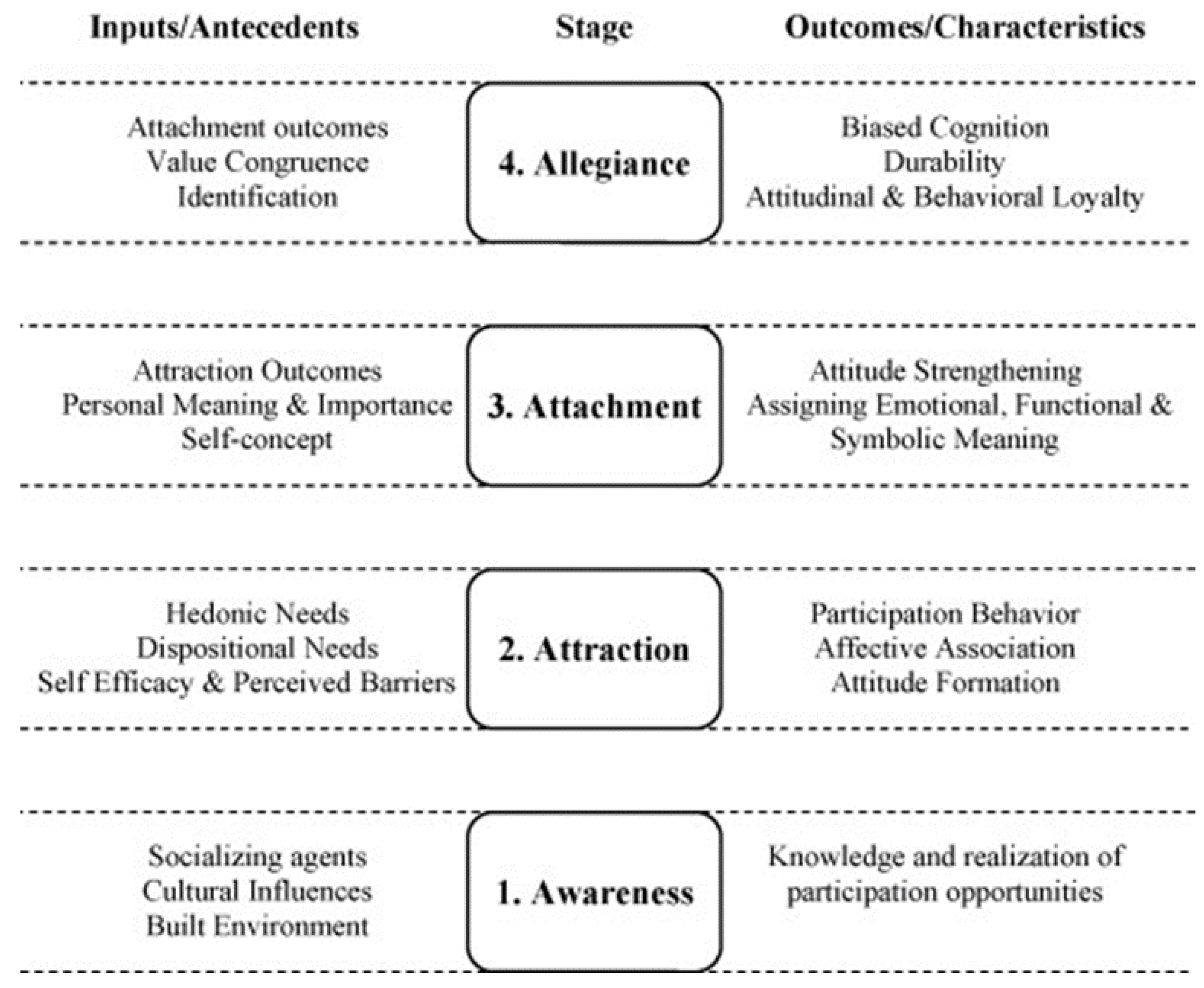

Funk and James [

23] developed the Psychological Continuum Model (PCM) in the field of sports involvement. The PCM framework was originally developed in the context of passive sport participation; however, it has been shown to also be a sound framework applicable to active participation in sport [

24,

25], sport internet behaviour [

26] and sport tourism [

27]. The framework is illustrated in

Figure 1.

2.3. Economic Approach of Sports Involvement

If we approach sports from the aspect of economics, it can be done on the one hand from the standpoint of consumption (active and passive activity) and on the other hand from the direction of exchange relation characteristics. From the first point of view, sports may be divided into two categories by their finance forms: (1) informal sport/leisure sport-sportsmen do not have contact with the sport market, they privately finance their sport pursuits; and (2) formal sport/competition sport-this latter type usually has a bilateral finance, since the individual and the state finance may also appear and influence the activity. From an economic point of view, in the formal latter case, informal sports can be discussed where there is no need for a market transaction, therefore, this activity is economically non-assessable by means of the usual tools, and there are also formal sports where the consumption of sports requires market transactions [

28]. The decisive factor of exchange relationships is the subject of the exchange: sports done by others as entertainment, attraction, or the physical activity itself. In the first case, direct income originating from or related directly to sports is the most important for the majority of athletes; sport is a job, where the fundamental objective is career improvement and the resulting additional earnings. In the second case, income resulting from physical exercise is not significant in terms of total income. In the third case, no income is generated from sports; the purpose of exercise is to maintain health and to spend quality leisure time [

29].

Nagy [

30], who distinguished two categories within formal sports (recreational sports and professional sports), applied a similar, likewise economical approach. In the case of recreational sports, the consumer in an economic sense is the athlete him/herself, who, in his/her free time, exercises physical activity due to the positive effect of sports on his/her own well-being and health. The consumer of professional sports is the audience seeking entertainment; for them watching sport events and the competition of professional athletes provides a value of enjoyment.

Separation of the two groups is justified by the difference in the aim of participation. Factors describing the first group concern the ones that are professionally engaged in sports. In this case, sports enthusiasts and spectators passively follow the event; they watch/listen to the event. Categories of the second group indicate the activities of people who actively participate in sports in their leisure time. For them, sport means recreation, a method of spending leisure time. Competitive and mainstream sports are in the middle; they have a meaning in relation with both groups, as they can be done professionally or during one’s leisure time [

31].

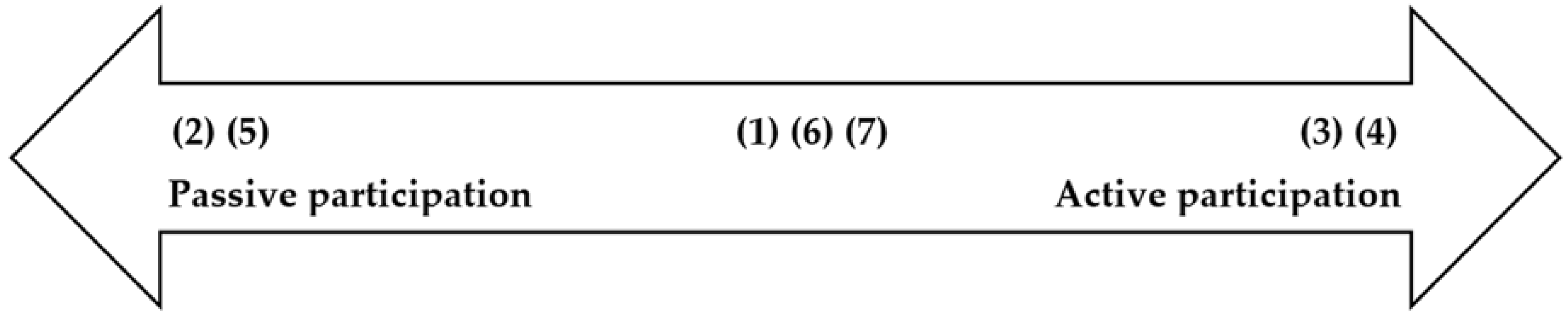

Active and passive sports consumers are usually distinguished based on these approaches, namely sports consumption may be manifested in several different forms between the endpoints of an active-passive scale. These forms might be: participation at a sports event/game as a spectator (1); following/watching of a sports broadcast in radio or television, reading of sports-related press (2); or participation at a sporting event, game as a player (3); active participation in recreational sporting activities (4); participation in sports-related computer games or involvement in online sports chat forums (5); or purchase of sports equipment (6); or sports ‘relics’/souvenirs (7) [

32]. Representation of these activities on an active-passive scale is shown in

Figure 2.

The most passive types of sport consumption are the following of sports news and participation in interactive sports games or communication (sport-themed computer games, online chat). Sports consumption as a spectator, purchase of sports equipment or sports relics/souvenirs require more activity from the individual. Participation is most active when an individual participates in sports itself, i.e., physical activity. This is realized when people engage in sports in their leisure time or are engaged in professional sports.

We highlight some of the most important, active and passive sports consumer descriptions from amongst the research results related to sports consumers.

As a summary of a number of studies investigating the causes of active participation, the validated Model of Motivation for Physical Activity Measure (MPAM) is mentioned. MPAM uses 30 statements to measure the most important motivational factors of the physical activity status of a person and based on that the level he/she represents within the journey towards an active lifestyle. Five factors can be emphasized as the reasons for participating in physical activity [

33]:

Enjoyment;

Appearance;

Social;

Fitness/Health; and

Competence/Challenge.

The characterisation of specifically active athletes is provided by the validated Sport Commitment Model. This model examines 58 statements and identifies 12 factors as explanatory elements for active sports:

Enthusiastic commitment;

Constrained commitment;

Sport enjoyment;

Valuable opportunities;

Other priorities;

Personal investment-loss;

Personal investment-quantity;

Social constrains;

Social support-emotional;

Social support-informational;

Desire to excel-mastery; and

Desire to excel social.

Behaviour of passive sport consumers is summarised in the Model of Sport Consumer Motivation [

24]. According to that model, the following five factors are the most important in the motivation of these sport consumers:

DIV: Diversion—“breaking out” of everyday problems;

SOC: Socialization—formation of new groups of friends, chance of meeting people with identical interests;

EST: Esteem—the feeling of belonging to a team, experiencing success and failure with the team;

EXC: Excitement—exciting and interesting game and performance; and

PER: Performance—the beauty of sports that presents itself in the performance of the athlete.

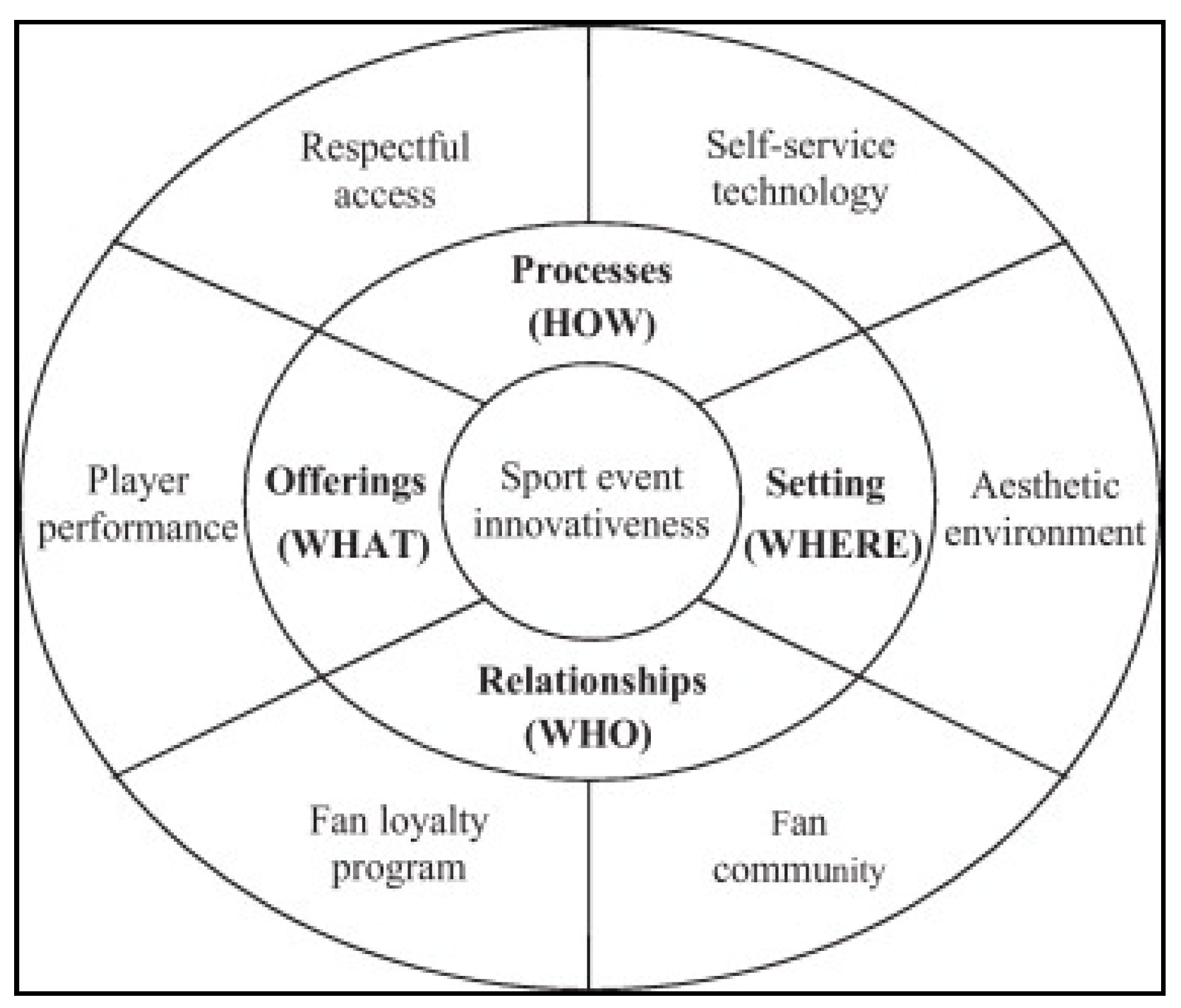

The background of participating in sport events is examined by the Model of Consumer-focused Sport Event Innovativeness. According to Yoshida et al. [

34], in order for the consumer to participate at a sport event, the event itself needs to be changed and renewed, since the performance of athletes is only a very small proportion within the motivation to participate (

Figure 3).

Communication with fans and the establishment of loyalty programmes is almost as important as they receive an experience from the sport event. This experience is what holds fan communities together.

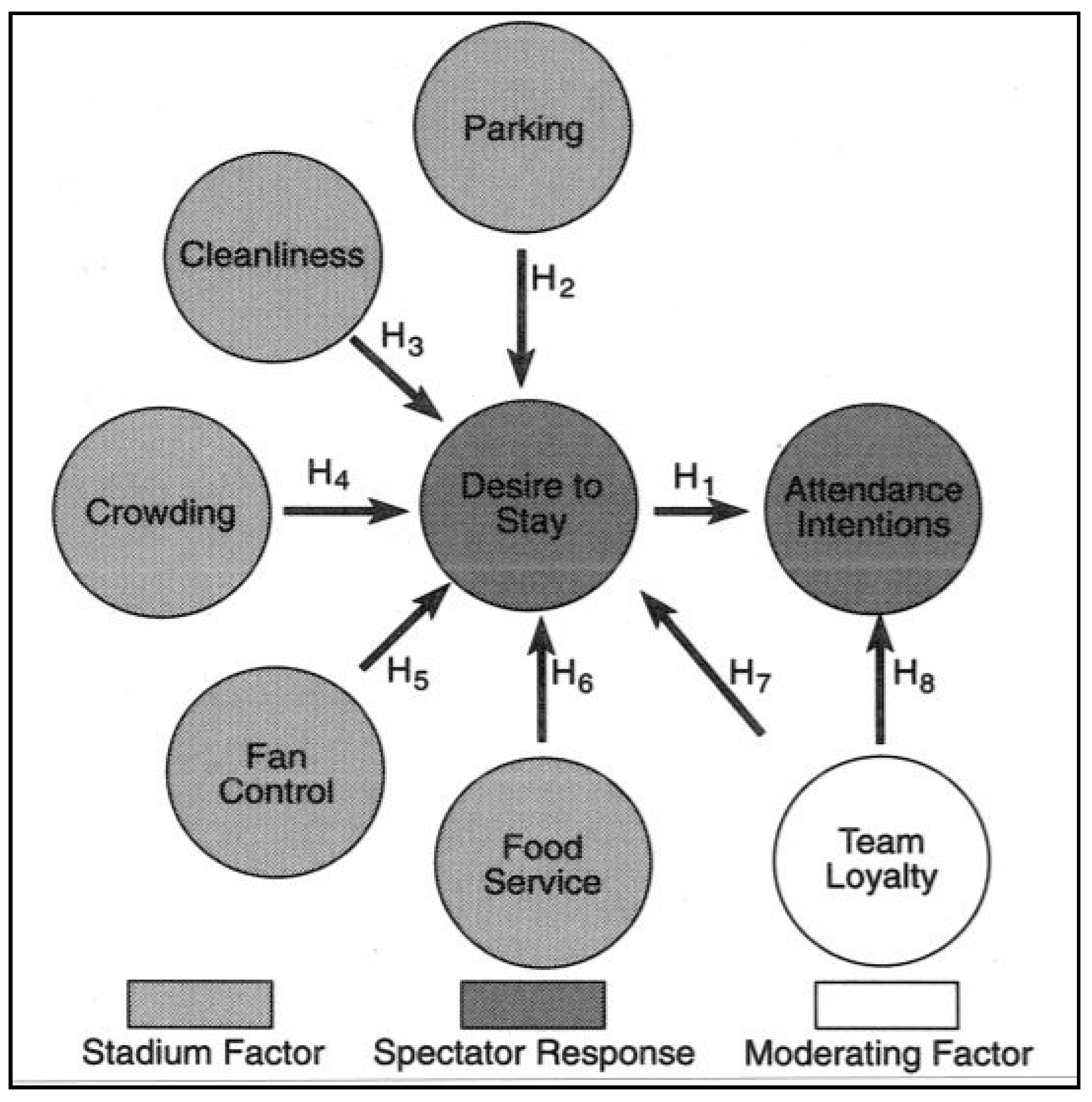

Obviously, the circumstances under which the sport event takes place are also important. Wakefield and Sloan [

35] intended to explore the features of sports facilities providing sporting experience. They sought to find out which effects cause sport consumers to root for their favourite team or athlete live at the location of the game. The results of their research are shown in

Figure 4.

Gammon [

36] in a private thesis urged the need for further theoretical analysis and novel models, which “not only illustrated the variety of consumer motivations but also highlights particular sport and tourism categories”. In his classification he has made distinction between sports tourism and tourism sports, as a consumer classification, and by doing this he has identified hard and soft definitions for both. Soft categories seem to be recreational or leisure forms, while hard categories include those activities, which either have relationship with competitive sporting event or sport “acts as an enrichment to the holiday”. These latter also seem to have a deeper economic dependence.

3. Materials and Methods

The main objective of our research was to reveal the sports involvement of people living in the North Great Plain region, namely to analyse their relationship with, and their commitment to, sports and to identify the main influencing factors for them to become sport consumers.

For the sake of a successful research programme, we applied multiple methods, including questionnaire surveys, targeted interviews, and case studies. By means of this so-called triangulation method as an approach, it is possible to avoid biased results since, in the course of triangulation, studying the same thing from multiple perspectives by means of multiple methods is likely to obtain more reliable and valid results compared to one-sided analyses [

37]. The main part of the analysis is the large quantitative survey, based on the opinion of 800 respondents, which requires some explanations. The questionnaire, itself, is a result of a private edition. The concept of sport involvement is an adaptation of the formerly-referred agricultural engagement, but all dimensions, variables, and attributes are our conceptual and original products. Trying to adjust to the requirement of rapid recording, we have defined, inside the six page questionnaire form, five dimensions, namely the (1) relationship between sport and people, such as the involvement level; (2) sport-related devotion and plans, such as loving/hating sports and associated plans; (3) sport politics and sport attitudes, such as the evaluation of sport promoting state motives; (4) favourite sport and attraction, such as favourite sport types, judgement of sport facility services, expectations towards a sports event, motives, and obstacles behind sports event participation; and (5) basic attributes of the respondents.

In the course of the regional survey, we carried out representative sampled queries within the regional population, quoted by age, gender, and settlement type, so the sample is only representative by these variables. This naturally means some limitations regarding the results, as it may only be relevant to the regional population. The sample height is very close to the most frequently-applied numbers, we have also calculated that this sample, based on the 95% reliability level, has a confidence interval 3.46, calculated by Creative Research System [

38]. The survey recording has been performed as an external commission, they have applied computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI), and all the results were recorded in SPSS programme (a statistical program of IBM, Armonk, New York, United States) charts, and then the collected data were evaluated. In addition to the descriptive statistical methods, contingency table analysis was performed by means of the chi-square test. Since the database has also allowed it, we have made further efforts in order to sharpen the statistical analysis, and tried to identify significant differences (by applying Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis tests) and attempted to verify possible relationships (by applying the Cramer’s V measure of association), in both cases between age, gender, settlement type, and the responses provided in the last part of the analysis.

Here, the main findings of the descriptive statistics (which illustrates basic distribution and specialties), the chi-square test (which reveals basic connections between specific variables), the results of the Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis tests, and the main findings of the Cramer’s V measure of association were put into the article, owing to the extent limitation of the article.

Interpretation of results was supported by targeted expert interviews that were conducted with members of sports committees at local governments, sport sociologists, and the executives of sport-related NGOs. In addition, case studies were conducted concerning sporting events and sports facilities. The completed interviews and case studies confirm and explain the results of the questionnaire survey, therefore, in this present study we only intend to present the questionnaire results.

Demographic data of the respondents involved in the questionnaire survey can be summarised as follows: 52.4% of respondents are women, 46.6% are men. Regarding age distribution, most of the respondents (22.13%) belong to the age group of over 60 years. The least respondents of the sample belong to the 18- to 30-year-old age group (12.63%). In terms of the level of qualification, it is clear that most of the participants in the sample have a higher education qualification (38.6%), while the proportion of respondents with the lowest level of education is only 3.8% within the survey. The highest proportion of respondents (32.13%) are active intellectual workers, and a relatively high number of involved people are retired (28.38%) and active physical workers (24%). The individual monthly net income of the majority of respondents (43.13%) is between 101,000 and 200,000 HUF (~330–650 EUR), but more than one-third of them have a maximum net income of 100,000 HUF (~325 EUR). One-tenth of the respondents did not answer this question. Three-quarter of the respondents classified themselves as the middle class, while one-fifth of them considered themselves to be within the lower class. More than two-thirds of the respondents live in a county seat, the proportion of people living in very small villages is barely above 10%.

4. Results and Discussion

According to the results of the attitude to sports (

Table 1), the share of respondents with an indirect attitude is only 13.3%, while the distribution of the other three categories are very similar to each other. Main categories were:

“I do sports and I deal with sports beyond that” means that someone is an official sportsmen or pursues sports as a leisure time activity; moreover, he/she also goes to sports events, or simply watches sports in TV/reads sports news);

“I only do sport” means that someone is a sportsman, or pursues sports as a leisure time activity, or sports necessary, for example, using a bicycle to go to work;

“I am only interested in sports” means, for example, someone goes to sports events as a fan, likes sports betting, collects sports relics, or even means sports voluntariness or sports employment, for example, as a coach;

“I have an indirect relationship with sports” means that other family members are pursuing sports or at home some sports instruments are not being used.

Results show that 25.5% of the respondents pursue sports and deal with sports beyond actual physical activities (e.g., professional or leisure athletes). Only 26.4% of the respondents chose the answer “I only do sport”, while 34.9% of them replied “I am only interested in sports”. A total of 13.3% of respondents are only indirectly linked to sports, which means that respondents are following sports in different media or, for example, they participate in sports betting. All respondents seemed to have any kinds of sports involvement. Most of the members of this category are those who have sports equipment at home, but they never use it.

Considering the survey results, the link between sports and population is strong; this is presumably due to the significant proportion of younger, more active, highly-educated respondents within the sample.

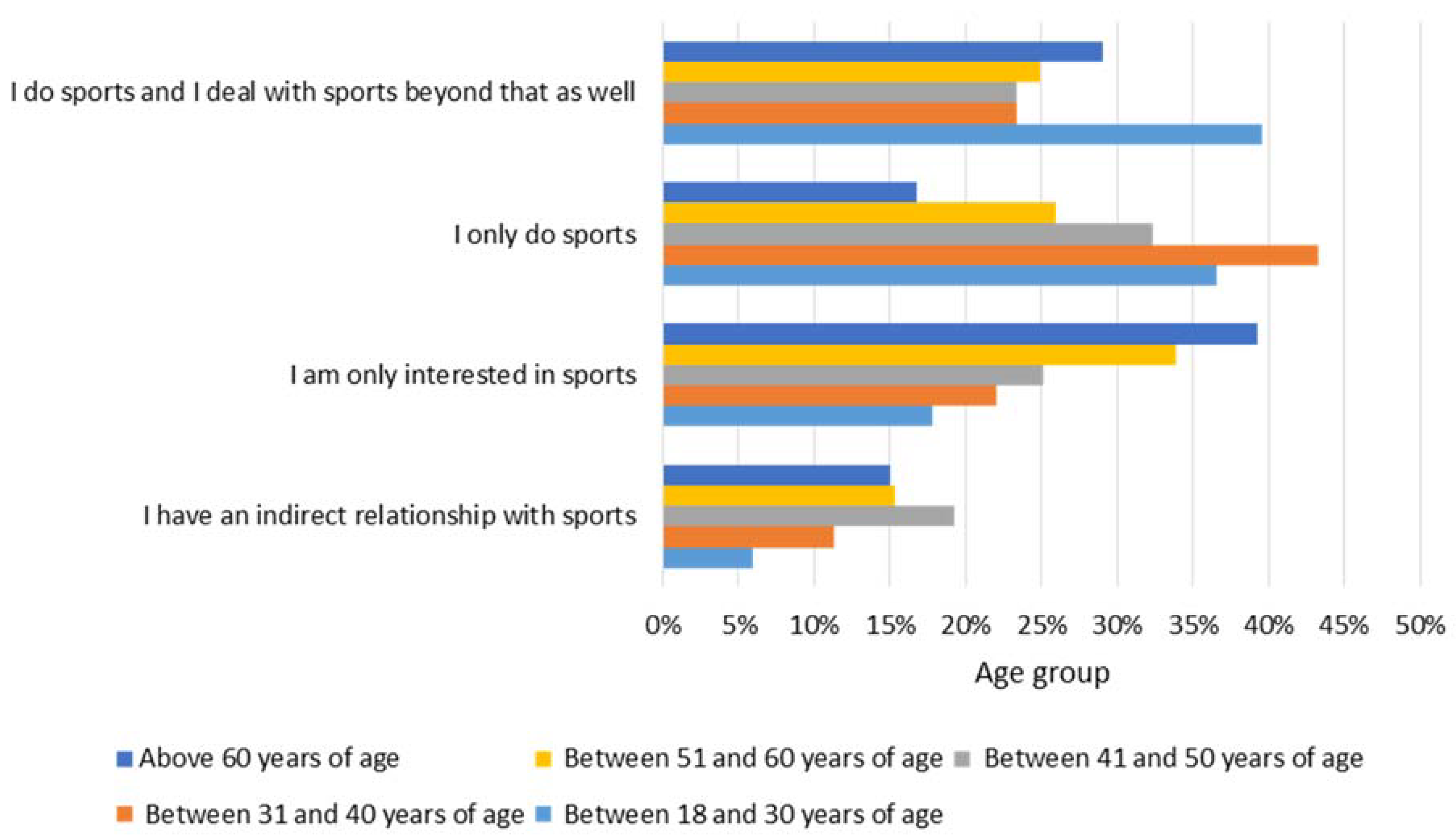

Figure 5 shows the connection between age and sports. Subsequently, data referring to the first four groups is analysed. There was a significant difference (

p < 0.05) in the attitude towards sports. The category “I do sport and I deal with sports beyond that as well” is the largest amongst 18–30-year-olds (39.6%), the response “I only do sport” was chosen mostly by respondents belonging to the 31–40 year age group, while the answer “I am only interested in sports” was the most popular amongst respondents over 60 years of age.

Table 2 shows the relation with sports based on gender and qualification. A significant difference can be seen (

p < 0.05) in terms of the relation of men and women with sports; the proportion of female respondents was higher in the case of the categories “I only do sport” and “I have an indirect relationship with sports”, the rest of the categories indicated the dominance of men.

Based on the results, respondents with higher qualification (university degree, PhD) have a much closer relationship with sports than the ones having lower qualifications, who are mostly characterized with indirect sports relationships.

In practice, this means that relationship with sports intensifies with higher school qualification, and that respondents with higher qualification are more aware of preserving their own health, therefore sports play a central role in their lives.

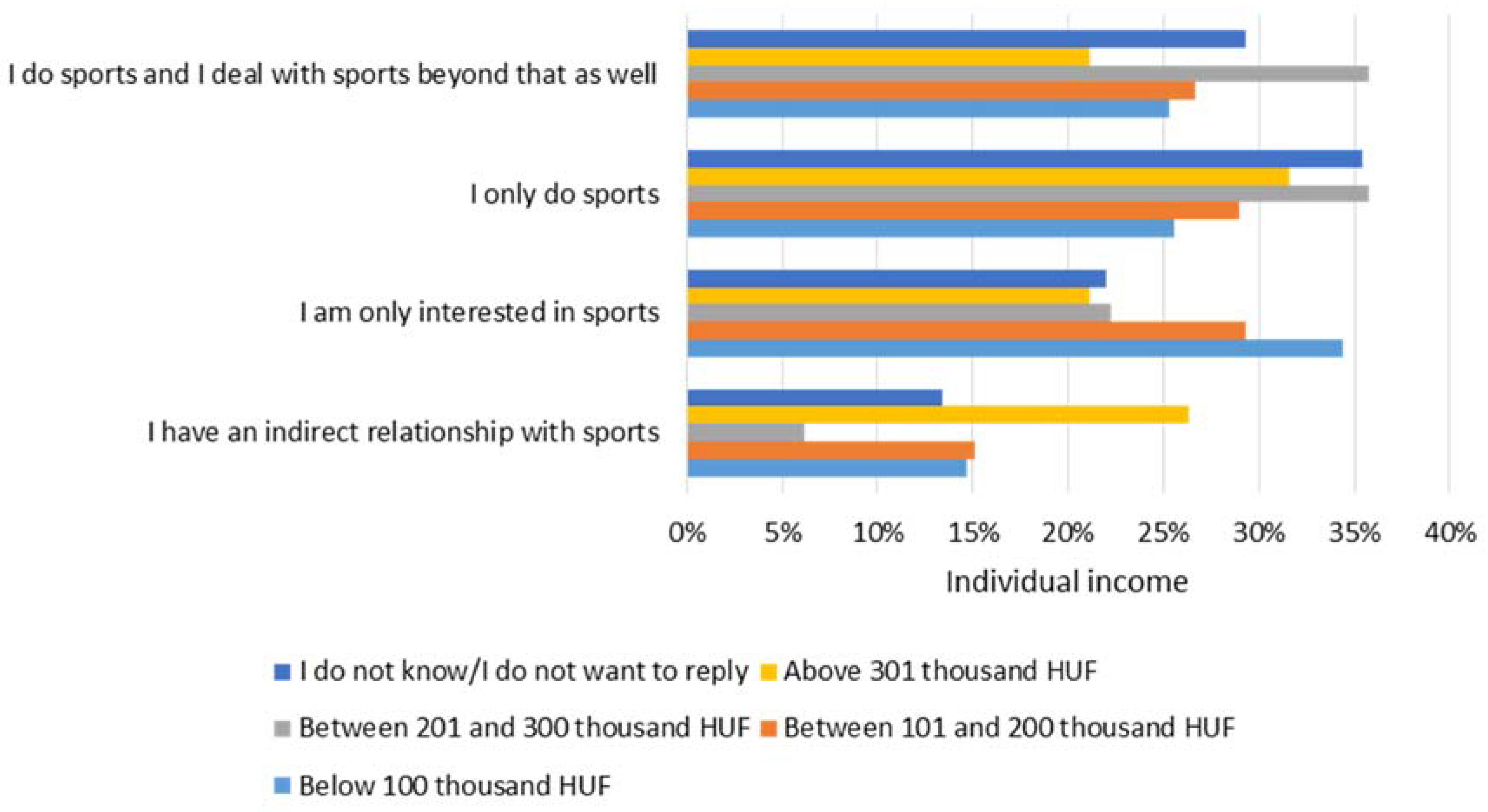

Figure 6 demonstrates the connection between sports and individual income. It is clear that the first two categories of direct engagement in sports are mostly characteristic of the group with 201,000–300,000 HUF of income; however, there was no significant difference between income levels and the attitude towards sports. Generally, this follows the approach according to which sport is highly dependent on lifestyle and not primarily on income.

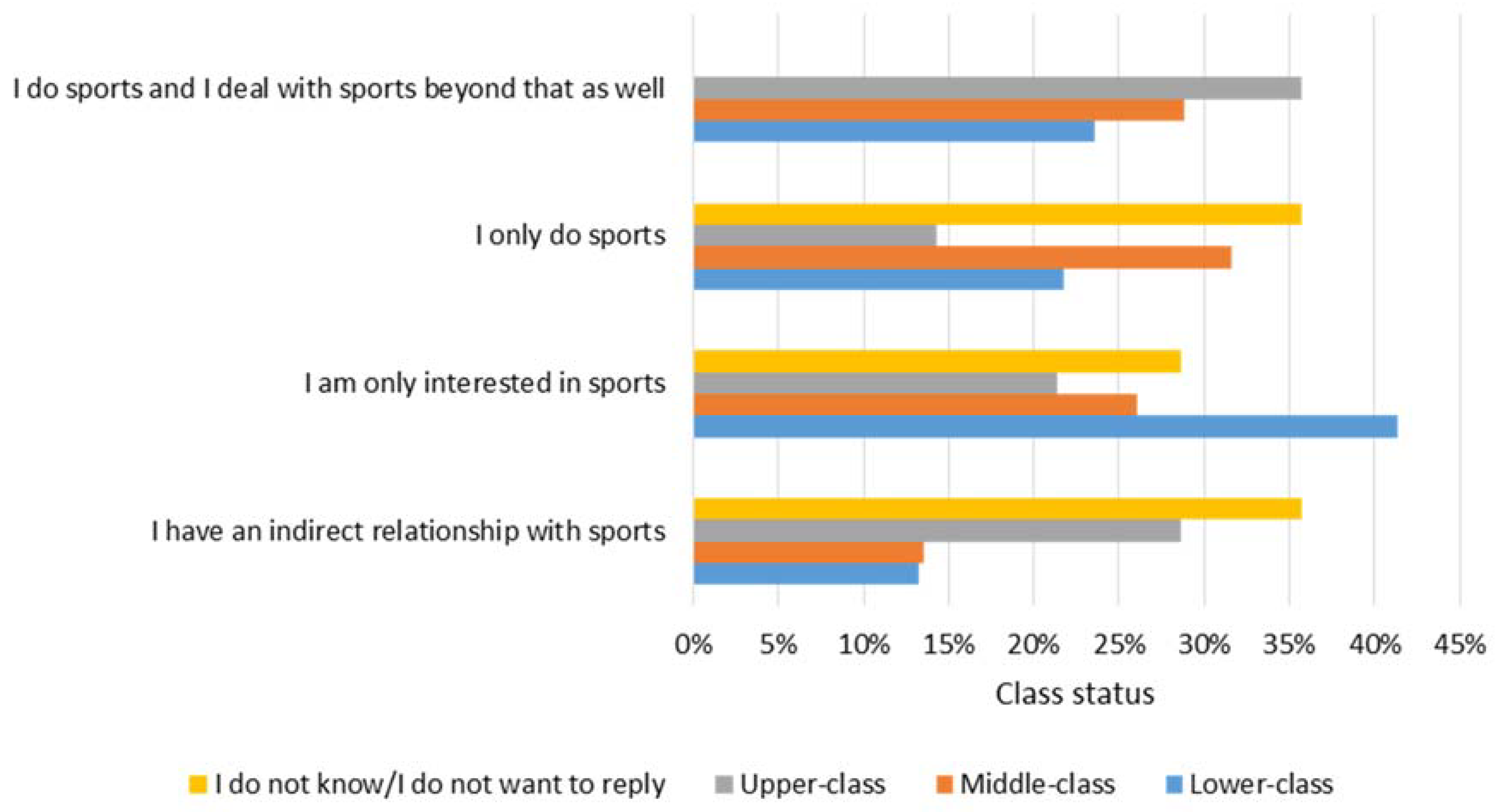

Figure 7 shows the correlation between the relationship of respondents with sports and their class status. There was a significant difference (

p < 0.05) amongst respondents with different class status; direct relationship with sports was mostly characteristic to the upper-middle class group, while indirect relationship characterized the group of lower class and non-respondent groups.

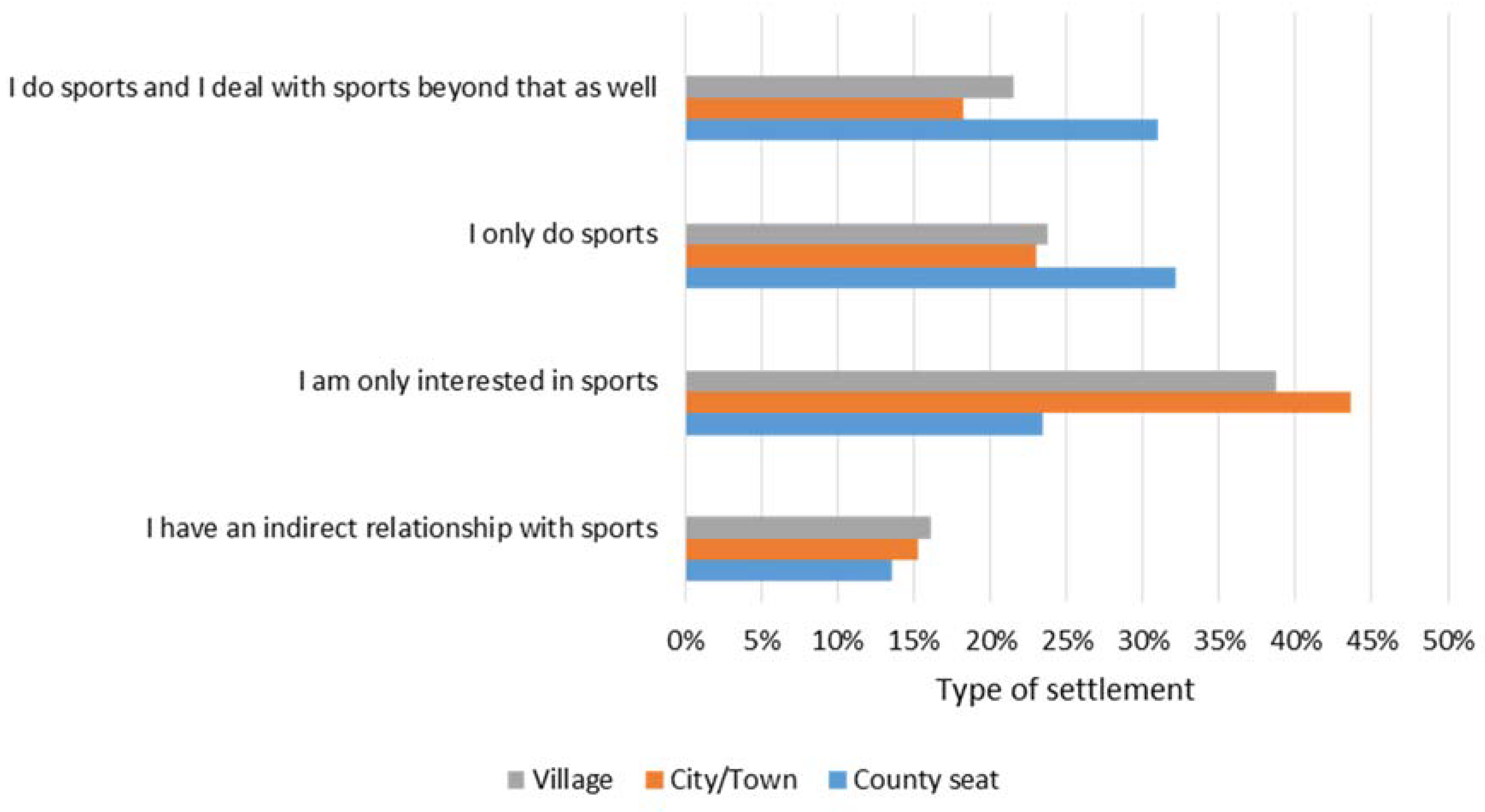

Figure 8 demonstrates the relationship of respondents with sports in terms of the type of their home settlement. There is also a clearly significant (

p < 0.05) difference between the county seats and the groups of towns and small villages; respondents living in county seats are more likely to have direct engagement, while people living in towns and villages mostly have an indirect relationship with sports.

This result can be considered interesting; in fact, it might mean that the relationship with sports is dependent on the location of residence and becomes stronger with the increasing size of the given settlement. Larger sports facilities and organized sports activities can usually be linked to larger settlements. There are fewer local opportunities for people living in smaller settlements, and traveling to the city might cause problems both financially and in terms of time management. However, parents are often still willing to commute so that their children have opportunity to engage in sports. It also happens that talented young people move to county seats to become a member of the chosen team.

Of the sample, 85.5% of the respondents answering, “I only do sport”, pursue sports in their leisure time, while one-fifth of them are forced to practice sport. This may result from the fact that they are unable to carry out other activities, entertainment, or going to work, unless they are engaged in some sort of sporting activity, like running, cycling, etc. Competitive athletes had a relatively low proportion, only 3.4%.

In schools and universities, regular physical education classes are mandatory; children and young people have no choice in this regard.

Based on the results related to sports-related attitude, it can be concluded that the majority of the respondents have a positive attitude towards sports and more than four-fifths (81, 63%) of the respondents love sports. Of these, 8.8% are sports enthusiasts and only 2.5% have selected the category “I do not really like sports”.

By the results, we can state that sport seems to play a determinant role in the lives of residents of the region; nearly 90% of them like it, so the role of interventions and steps related to it are clearly explainable. There may be a number of reasons for a positive attitude to sports, because the health-preserving role of sport does not appear only physically. Sporting also has a beneficial effect on mental health, and belonging to the sports community is a social protective factor that may contribute to the development of one’s healthy personality.

According to results concerning sport-related plans, more than one-third (34.6%) of respondents answered that they plan to spend more time with sports in the future and 62.1% did not want to change their sports-related habits. Only 2.6% of them have chosen the option to spend less time with sports in the future.

The results—in conjunction with the first results—according to which nearly 60% of the respondents do not want to change their sport-related habits, and nearly 30% intend to do more sports, unanimously underlines the role of sport. More and more individuals recognize that sports are indispensable for the preservation of their health, and when asked, they tell that they plan to do (more) sports in the future. However, the actual proportion of people who really start changing their lifestyle remains a question.

Respondents were asked to evaluate the role of sport, on a scale of 1 to 5. The highest average score (4.62) was given to the role of sport which improves human relationships and develops social life. The statement according to which sports achievements acquired by domestic athletes are very important in terms of the reputation of the country also received a high average score (4.52). The statement saying that sport depends on determination and the individual received an exact same average score (4.52). The assertion according to which domestic athletes are not appreciated enough and that Hungary is a sports nation are on the bottom of the list (average scores of 3.68 and 3.48 respectively).

The next segment dealt with the opportunity to strengthen sport-related attitudes. Respondents were able to consider multiple alternatives and to mark multiple responses in relation with the question how to increase positive attitude towards sport. Almost two-thirds (64.4%) of respondents thought that sports associations and different organizations involved in sports could contribute to a strengthened attitude towards sport. They had similar opinion about individual-level motivation (e.g., financial support or benefits from the state, employer); 63.4% chose this answer while the support of sports events (domestic and world championships) was selected by 57.75%. According to some respondents, the attitude towards sport is impossible to change (1.9%). Fortunately, this rate can be considered low.

Analysis of Sports Involvement in Terms of the Level of Attendance of Domestic Sports Events

The tests also involved the examination of domestic sports that are the most popular amongst the participants of the research. They had to indicate a maximum of three names in the order of their importance. With regard to sports, it can be stated that the first places mostly include ball games (football, handball, and water polo) and swimming. These are followed by athletic sports, and the less known/widespread/popular ones. Football is still towering the list, many people love it; perhaps the rarity of mentioning the other extreme indicates the lack of pluralism.

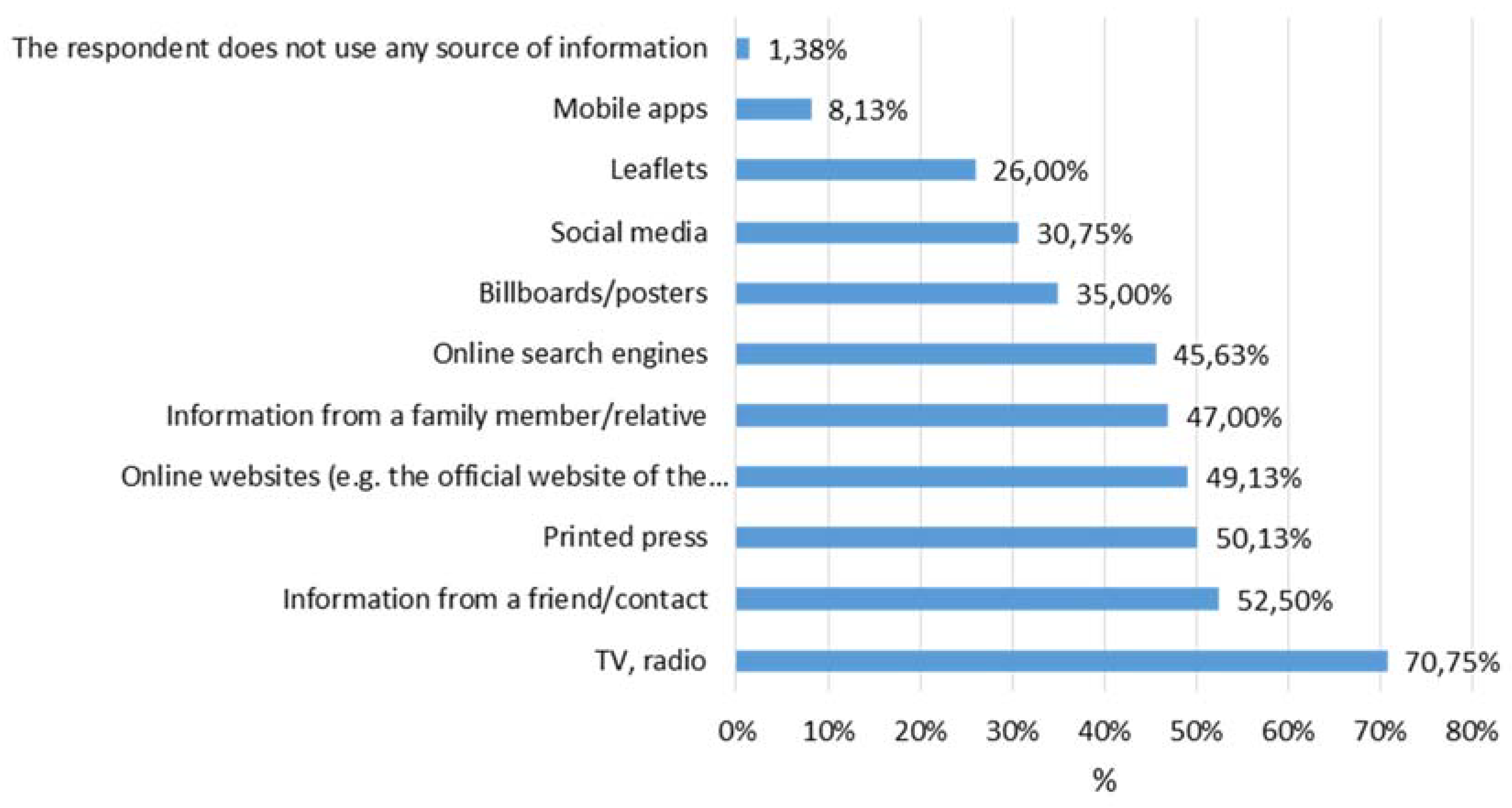

In the course of studying the level of informedness on sporting events, the task of respondents was to choose from the listed sources of information (they could indicate more than one) the ones that they use in relation with sports events.

Figure 9 shows the obtained results.

In order to obtain information related to sports, television and radio are used in the largest proportion (70.75%). More than half of the respondents indicated friends and other contacts (52.5%) and the printed press (50.13%) as the primary source of information. Demonstrating the expansion of mobile applications, almost one-tenth of the respondents use a mobile application to acquire information. The role of TV/radio does not come as a surprise; they have played a significant role in the lives of people. However, what is more interesting is that they use a large variety of sources for gathering information. There is a significant difference between different generations in relation with inquiries. Online channels are becoming more and more important among younger generations.

Respondents also shared their comments on the approximate frequency of their visits at various sports events; 39.4% of respondents go relatively rarely, while 26.13% never attend any sports events. By contrast, only 17.1% of them root for their team live, and 17.4% visit sports events occasionally.

In the next segment of the survey, respondents had to consider services available at different sports events. In connection with the listed services, they had to decide whether these services were available at the events they visited and, if yes, whether or not they were using it. Additionally, they had to state that if there was no such service, then, if introduced, would they use it or not. Percentage allocation of the responses given in relation with the services is detailed in the table included in the

Appendix A.

Watching sports events on a giant display had the highest proportion (48.2%) followed by the moving buffet and Facebook. “Kiss cams” and mobile applications for statistics are the least important for respondents.

The giant display reflects visibility-related requirements, while the frequency of, and demand for, the personalisation of events (e.g., joint photos) represents a certain kind of attitude. Internet-based services are becoming increasingly popular among younger generations, which is reflected by the findings as well.

In the course of our survey, we also asked which expectations influenced the respondents positively regarding a visit to a sports event. Respondents had to evaluate the listed options on a scale of 1 to 5. The meaning of 1 was that it has no influence at all, while 5 meant that the option has a full influencing effect. The mean values were between 3.63 and 4.44, so the findings are relatively homogeneous. Based on the results, the most positive influence is affordable ticket price (4.44) followed by an audience that behaves in a civilised manner (4.30) and the provision of satisfactory conditions (4.2). Respondents also considered important the clear access to sports events (3.95), and easy access to public transport for fans with season tickets (3.92). Also important was the good performance of the team at home games (3.88) and, of course, the successful participation in international leagues (3.85). Respondents considered the adequate quality of buffets the least important (3.63).

Civilised recreation at affordable price; it is interesting that the performance of the team/athlete is less important than these values, which means that the recreational function of the participation at sports events can be considered the primary preference.

Attendance of sports events is influenced by the fact that most individuals are price sensitive and the need for security appears through the declared importance of a civilised fan audience.

Respondents had to evaluate the factors that prevent them from rooting for their team on a scale of 1 to 5, considering the extent to which these factors influenced their attendance at an event, where 1 has no influence at all, and 5 has a full influencing effect. The mean values in this case were between 2.67 and 3.96.

From amongst the factors preventing fans from rooting at a live event, the highest average score was given to the actions of racist and aggressive fan groups (3.96). This is followed by too expensive tickets (3.64) and the quality of sports facilities (3.38). These are followed by large distance (3.24), lack of interest (3.09) and the problems associated with the purchase of tickets (3.03). Bad weather reached a mediocre average of 3.02, while the attitude of the management of the sports association towards the fans was somewhat below that (3.00). The least influential factor according to the respondents was size of the crowd (2.85), live television broadcast (2.77), and the fan card (2.67).

It is not surprising that the lack of attractive values is a fundamental influencing factor in terms of being absent from live events. Uncivilised audience is the primary reason for fans deciding not to attend an event.

The next group of questions of the questionnaire concerned whether an individual is a member of a club, what kind of emotional attachment aspects would be attached to the club membership. Mean values of the results are relatively homogeneous (mean values ranged from 2.91 to 3.45). According to the opinion of respondents, attachment to the club is mostly influenced by the long-term success of the sports association (3.45). Regular information and communication by the club is the second most important factor in forming a bond (3.37). This is followed by social involvement of the club (3.17) and the formation of groups of friends (3.13). Short-term success of the club is less decisive (3.04), which is also true for the attitude of the club towards fans (2.99). Family motivation is the least dominant in the formation of attachment (2.91).

According to the evaluation of the respondents, there are two important factors in this regard; on the one hand, since the values are quite low, some other factors might also have a role in the attachment. However, performance and successfulness are definitive in terms of the rest of the attributes, namely if attachment is successful, probably the opposite might prove true as well, according to the above.

Performing the Mann-Whitney test on the database to reveal significant differences between gender, age, settlement type, and the dependent expectations, attendance, and emotional attachment aspects related attributes has resulted in some interesting results. We have found gender-related significant differences, since the clear access to sports events, the provision of satisfactory conditions, an audience that behaves in a civilised manner, affordable ticket price, financial reasons, racist and aggressive fan behaviour, and overcrowded match were all those attributes, which equally, obviously were emphasized by females, which means that females express a more explicit expectation towards the cultured and cheaper event. A Kruskal-Wallis test has revealed some significant differences by age, and it seems that behavioural attributes, such as the racist and aggressive fan behaviour, is more frustrating for the elder ones and an audience that behaves in a civilised manner is also significantly better expected by them. Moreover, the performance of the team is also significantly important for the elder generations, shown by the values of the mean rank. Regarding differences by the respondents’ settlement type it seems that significant difference was found in relationship with the accessibility of the sports events, village dwellers emphasized purely the accessibility-related attributes that prevent them from supporting, since distance, difficult access to tickets, and even financial issues were highlighted by them.

By applying the Cramer’s V measure of association to reveal relationship strength between the independent variables, such as age, gender, settlement type, and dependent expectations, attendance and emotional attachment aspects related attributes in the last part of the analysis, we have also found some relationships, although the strengths of them were mainly slight. For example, the clear access to sports events attribute and gender type relationship proved to be significant, but Cramer’s V only was only 0.152, which shows a slight relationship. Other attributes, which have also shown a slight relationship were illustrated in

Table 3. Briefly it is worth noting, that easy accessibility, financial issues and pleasant entertainment are more special expectations and issues of female compared to the male, similar expectations together with the performance of the team are more emphasized by the elder one, and notably distance, as an attribute slightly more matters for the village dwellers.

5. Conclusions

Currently, a healthy lifestyle is being increasingly emphasized on a global scale, and special attention is given to increasing the amount of time dedicated to sports and physical activities. The relationship between sport and sustainability has focused on numerous approaches lately. It seems that social aspects and components have been excluded from the focus of sustainability, and not purely the relationship between sport and environmental issues, but even social aspects should be considered. Sports can improve public health benefits, may have an impact on academic achievement, future employability, building skills and confidence, and these effects may last for several decades. So as to understand sustainability issues, sports-related examinations should also focus on, and reveal, the more comprehensive relationship between sport and the society itself.

In our research, we examined the sport involvement of the North Great Plain region, discussed the factors influencing the attendance of sports events, including the ones related to sports facilities. Naturally, the limitations (owing to the nature of the sample) influence the application possibilities and reliability of the results. Based on the results, and owing to the methodology developed, it would be advantageous to enhance the reliability and try to launch a national level survey, since the methodology and the results may contribute to a better understanding to the relationship between sports and the society itself on national level, and by doing this also contributes to sports political decision-making. Based on the results it seems that half of the respondents do not engage in sports at all; this result is in conformity with the results of the Eurobarometer survey. A quarter of the respondents do only sports and the proportion of athlete-fans is the same. Younger age groups, women, and highly-qualified and well-earning active, intellectual employees have a stronger commitment towards sports and they exercise more, as well. In terms of commitment towards sports, respondents mostly agree with the statements that sport improves human relationships, determines the reputation of the country and that exercise is a matter of individual decision. In terms of local attachments, the significance of football is outstanding, while respondents also mentioned swimming, handball, water polo and their related athletes, and clubs. The most determinant factors of club loyalty are regular communication, social involvement, collective experience, and long-term successfulness. In terms of the attendance of sports events and the services of sports facilities, it was found that sport consumers seek civilised, affordable, and secure services. Further efforts in order to sharpen the statistical analysis have revealed significant relationships by age, gender, and settlement type, where female, elders, and rural people showed emphasized expectations, and the results of the Cramer’s V measure of association to reveal relationship strength indicated some specific relationships, although the strength of them were mainly slight.

With our research results, we intended to contribute to the elaboration of regional sports strategies.