Abstract

The sustainability challenge requires experimentation with innovations, followed by an upscaling process towards a broader regime change in the long term. In Europe we observe various regional hotspots for sustainability experimentation which suggests that there are favorable spatial contexts. Little is known about why different kinds of experiments flourish or fail in various spatial contexts. In this paper we explore these contexts by using the habitat concept. A habitat is regarded as the configuration of favorable local and regional context factors for experimentation. To capture the diversity of these habitats we have constructed archetypical experimentation patterns. These patterns are built up of five dimensions: knowledge, governance, informal institutions, regional innovation advantages, and social learning. In a comparative case study in four city regions in Europe we find a large contrast in habitats. Countercultures play an important role, as they shape a beneficial context for experimentation through alternative ideas and lifestyles. We also find indications that it is important that a combination of several habitat factors is present, and that these factors have aligned and evolved over several years of experimentation, thus leading to a more mature habitat. The research suggests that regional stakeholders can positively influence most of the habitat factors shaping future upscaling. However, there are also some important factors, such as regional knowledge and skills, which have a path-dependent nature and are more difficult to improve in the short term.

1. Introduction

Sustainable development is arguably the most important societal challenge of our time. This challenge requires several transitions. In the first phase of these transitions, an important activity is to experiment with sustainability innovations. A series of experiments may contribute to an upscaling process towards a broader regime change in the long term [1]. It is important to consider the local and regional scale to learn what works and does not work in specific spatial contexts. Cities are seen increasingly as agents of change [2], as ideas spread more easily in densely populated areas because of proximity advantages. Moreover, cities increasingly see themselves as laboratories (i.e., experimental places) where innovations can be trialed ([3]). Experimentation is increasingly regarded as a governance strategy that may serve as an alternative to conventional predict-and-provide forms of urban planning [4].

While observing patterns of urban sustainability experimentation in Europe, researchers have identified particular regional hotspots for various types of sustainability experiments. For example, Berlin is well known for its grassroots food experiments [5] and for its leading role in urban energy transitions [6], and Barcelona and Toulouse are known for their fab labs [7]. It is relevant to ask ourselves why these localized densities of experiments exist [8], whether distinct regional contexts such as social or institutional factors make cities and regions favorable for experiments, and whether different local arrangements give rise to different patterns of experimentation [9].

More generally, these questions deal with the topic of how the spatial context matters in transitions. This topic is being studied in an emerging and exciting research field: the geography of transitions. Recently, the literature in this field has expanded considerably [10]. We are interested in a specific phase of transitions, namely the phase of experimentation. As a contribution to this research field, we have recently developed the habitat concept [11]. The habitat is defined as the configuration of the most important spatial context factors enabling the future upscaling of sustainability experiments. We empirically found that these factors, such as the existence of a vision and of regional multi-actor networks, are deeply embedded, both locally and regionally.

The various types of sustainability experiments may flourish in specific habitats [11]. For example, grassroots energy experiments may flourish in a transition town, and guided high-tech living labs may flourish in a science-based campus milieu. We are interested in capturing these contrasting habitats and in the dimensions that cause this contrast; hence, our research question is the following: which spatial context factors enable the future upscaling of sustainability experiments in contrasting regional habitats in Europe, and can these factors be influenced in a positive way? It is important to clarify here that in this research we are interested in how to anticipate future upscaling of experiments during experimentation; we are not analyzing the actual upscaling process. This requires a predictive approach in our research design. We believe that a better understanding of contrasting habitats and upscaling factors would help to give the stakeholders involved in these experiments more tailor-made support for experimentation, including an improved understanding of how different contextual factors shape different patterns in experimentation.

The paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 provides relevant insights from the literature on the geography of experimentation and proposes an analytical framework. Section 3 specifies the methods used, Section 4 describes the findings in four cases, and Section 5 discusses and reflects on the results. Finally, in Section 6 a conclusion is presented and an agenda for future research is developed.

2. Previous Research and Conceptual Framework

2.1. Constituting Dimensions of Habitats

In this section we discuss analytical dimensions in spatial contexts from previous research. We primarily use the transitions literature and the literature on regional innovation systems. Various spatial context factors may enable sustainability experiments in their future upscaling. Although research suggests that experimentation is often embedded in multiscalar networks [12], the factors that shape experimentation are mostly manifest at the local and regional scale and are entangled in path-dependent places. Hence, the landscape of experimentation is geographically uneven; in other words, the potential for experimentation varies across space [10,13].

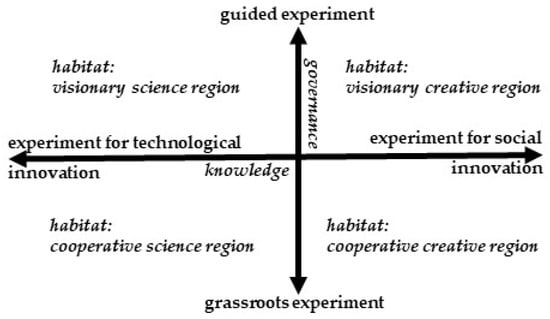

The starting point for this research is the habitat concept. A habitat is defined as ‘the configuration of the most important spatial context factors enabling the future upscaling of sustainability experiments’. The habitat concept is related to several other concepts in the literature, such as fertile soil and the Territorial Innovation Model (TIM). (Fertile soil is understood to be a rich and diverse social texture for the emergence of new sustainability initiatives and the continuation of the existing ones. However, this concept is limited to the context factors for grassroots experiments [14]. The habitat concept has a broader scope, and also includes guided experiments. A TIM is a model for regional innovation in which local institutional dynamics play a significant role. Several elements of a TIM have a path-dependent nature. TIMs and innovation ecosystems are focused on innovation for economic restructuring and enhanced competitiveness of regions. TIMs do not consider the noneconomic spheres of regional communities [15,16]. The habitat concept has another scope; it is focused on innovations for sustainability, which have more difficulties in scaling up than do economic innovations [11]. When comparing TIMs and habitats, it is also important to note that habitats are not equal to regions. We suggest that habitats may overlap in a geographical sense [11]; for example, a large city may offer favourable spatial context factors for grassroots food experiments as well as for guided technological experiments.) However, the concept in essence is a further elaboration of the niche concept in the strategic niche management literature. In this literature, a niche is defined as a ‘protective space’ [17]. With the exception of a few notable contributions (e.g., [18,19,20]), the geographical dimensions of the niche concept have not yet been made explicit. The habitat concept explicitly focuses on these geographical dimensions. In previous research we empirically found that experimentation is locally and regionally deeply embedded and we constructed a conceptual framework for a typology of experiments in favorable habitats; see Figure 1 [11].

Figure 1.

Typology of sustainability experiments in favorable habitats. Adapted from [11].

To describe the various types of experiments, we made a distinction in two dimensions. First, for the governance dimension, we suggested that there is a contrast between ‘guided experiments’ and ‘grassroots experiments’. Second, for the knowledge dimension, we suggested that experiments for technological innovation are different from experiments primarily focused on social innovation. Using these two dimensions, four contrasting regional habitats have been constructed. We found that the following four generic spatial context factors for enabling future upscaling are most important: cooperation in local and regional networks, policy instruments from local and regional governments, dissemination of learning experiences and a local or regional vision of the future. However, we also found some first indications that there are distinct favorable spatial context factors for various types of experiments. These were the following:

- The existence of a local or regional vision is more important in the upper quadrants of Figure 1.

- The availability of regional knowledge and skills is more important in the quadrants on the left-hand side.

- A cooperative culture is more important in the lower quadrants.

- Trust is more important in the quadrants on the right-hand side.

The aim of this study to systematically explore similarities and differences across the quadrants as described in earlier research (see Figure 1). The main dimensions in the current research are thus formed by ‘type of governance’ and ‘type of knowledge’. As a second step, we add secondary dimensions by mobilizing additional insights from literature. These secondary dimensions are used to enrich the existing four quadrants. We remark that the dimensions are not distinctly geographical in nature; however, they are selected because the existing literature highlights these dimensions as localized, i.e., they vary across space, and at the same time they are relevant for sustainability experimentation. Thus, they might describe the uneven geographical landscape of context conditions for experimentation.

The literature provides three secondary dimensions describing the uneven landscape of spatial context conditions. First, in their literature review on the geography of transitions, Hansen and Coenen [10] mention three themes which are related to experimentation: urban and regional visions and policies (relating to the habitat dimension ‘type of governance’), local technological and industrial specialization (relating to the habitat dimension ‘type of knowledge’), and ‘informal localized institutions’. Second, the regional innovation systems literature provides an additional dimension concerning ‘regional innovation advantages’. These advantages have a broad scope (see [11] for an overview). Here, we focus on the localized capabilities enabling regional innovation. Third, we add a dimension concerning ‘social learning’. Social learning is a key process in sustainability experimentation [19]. There are some indications that learning processes are localized [21,22]; however, we believe that this localization requires further research. The resulting five dimensions are discussed below. We note that the discussion aims to contrast the four habitats, so as to clearly bring out their differences. As such, the discussion is an analytical simplification of, arguably, much more complex realities in actual regional habitats in the real world.

2.1.1. Type of Governance

This dimension deals with the geographical variation in context factors between guided and grassroots experiments. Guided experiments are coordinated by governments or firms. (In Section 2.1, the most important elements of the five dimensions are placed in italics. These elements will be used in the synthesis at the end of this section.) These experiments are enabled by a clear regional vision or a strong economical specialization [10]. A regional vision may function as a selection environment for experiments and development pathways [23] and as a tool to mobilize a group of actors [24]. A strong economic specialization shapes the development of innovations necessary for sustainability transitions [10]. Guided experiments flourish in a habitat or region with strong guidance from governments or firms [25].

Grassroots experiments are emerging bottom-up, at least from the perspective of the local or regional government. They are self-governed by the civil society; they may consist of voluntary associations, cooperatives, and informal community groups. These experiments are often more loosely structured and do not always result in formally documented institutional learning. The learning is tacitly held within people, rather than consolidated in readily accessible forms. The small scale and the geographical rootedness make scaling up difficult [26]. Global platforms of experiments, such as platforms for community-supported agriculture or fab labs stimulate the exchange of knowledge between experiments. However, some of these platforms struggle to define their form and purpose [7]. These experiments may flourish in a habitat with low specialization [25] and with a cooperative culture [27].

2.1.2. Type of Knowledge

This dimension relates to the geographical variation in knowledge conditions. Experiments for technological innovation produce mainly codified knowledge [28]. This knowledge is acquired mainly by first-order learning, i.e., learning which leaves fundamental notions, preferences, and values in society intact [29]. This codified knowledge might be easily disseminated by ‘global pipelines’, which create openness to the outside world, i.e., with selected providers outside the local milieu [30]. These experiments may flourish in a habitat with science-based innovations [31], in a region with a particular technological specialization.

Experiments for social innovation produce mainly tacit knowledge. This knowledge is acquired mainly by second-order learning, i.e., learning which may result in major changes in an actor’s strategic choices, objectives, values, and preferences [29]. This tacit knowledge might be difficult to transfer between subsequent experiments in different regions [28,30]. These experiments may flourish in a habitat with creativity-based innovations [31] in a region with a specialization in services.

2.1.3. Informal Localized Institutions

Localized institutions are defined as territorially bound norms, values, and practices; they have a major influence on the uneven spatial landscape of sustainability transitions [10]. This unevenness occurs between regions and between localities, e.g., specific local cooperation cultures and attitudes towards knowledge sharing [18]. Related to informal territorial institutions is the concept of an alternative milieu. Longhurst [8] illustrates how a localized concentration of countercultural practices, institutions, and networks may support sustainability experimentation. An alternative milieu may have a regional scale. Longhurst presents the following five forms of alternative milieus: radical politics, new social movements, alternative pathways, alternative spiritualities, and alternative lifestyles. In his case study on the village of Totnes, a so-called Transition Town, he shows that after almost a century of experimentation a localized milieu was formed, with a growing proliferation of alternative practices, institutions, and organizations [8]. We can understand this formation as a process in which experiments and habitat co-evolve. Hielscher and Smith [7] add that such countercultural movements are often the birthplace of major advances in technology. These alternative milieus may offer a space for creating alternative ideas, practices, and social relations [32], and are therefore highly relevant for transitions. An alternative milieu suggests strong connections with grassroots habitats [7], i.e., the lower quadrants of Figure 1, but it may be also relevant in other habitats.

2.1.4. Regional Innovation Advantages

Regions have distinct advantages for sustainability experimentation. The literature on regional innovation systems describes a wide variety of factors explaining the spatial clustering of innovation. These factors partly overlap with other dimensions described in this section, particularly with the ‘type of knowledge’ and the ‘informal localized institutions’ dimensions. Here, we focus on the economic specialization and the localized assets and capabilities enabling regional innovation.

Firms may profit from agglomeration economies, for example, regarding labor supply, generic infrastructure, and learning opportunities [33]. Green innovations are stimulated by factors such as a pool of skilled labor, supporting intermediary organizations, research institutes and universities [34], and localized assets and capabilities (e.g., infrastructure and institutions). The path-dependent nature and slow evolvement of such assets and capabilities make them difficult to imitate [21,35].

Boschma [36] mentions the advantages of institutional proximity for innovation. This includes the sharing of institutional rules of the game, habits, and cultural values. This proximity promotes knowledge transfer, interactive learning, and (thus) innovation.

2.1.5. Social Learning

Social learning is a necessary precondition for change towards sustainability [37], and it is a key process in sustainability experimentation [19]. Social learning deals with learning in groups, within a region as well as between regions. This dimension partly overlaps with the dimension ‘type of knowledge’. For social learning we use the definition by Sol et al.: i.e., ‘an interactive and dynamic process in a multi-actor setting where knowledge is exchanged and where actors learn by interaction and co-create new knowledge in ongoing interaction’ [38]. Social learning in a region is stimulated by regional multi-actor networks, and the diversity of actors involved enables a broad understanding of the issues at stake. The emergent properties of interaction in these networks are trust, commitment, and reframing (e.g., acquiring new insights and perceptions) [38]. The strong-tie relations within a region allow stakeholders to build trust and to exchange tacit knowledge. However, Boschma [36] shows that tightly coupled networks run the risk of being locked-in (meaning that there is a lack of openness and flexibility) in specific exchange relations between network partners. As a possible solution for this lock-in, Boschma suggests creating loosely coupled networks, which are open to knowledge from the outside world. Learning between regions is necessary, for example, for transferring experiments to other regions, and the dynamics may be different to those found for learning within a region. Various global networks of sustainability experiments, such as platforms for transition towns, fab labs, and community-supported agriculture, promote the exchange of codified knowledge and generalized (non-context-specific) frameworks [39,40]. Some of these platforms struggle to define their form and purpose [7].

In this section, we concluded that the literature shows that different local and regional contexts may enable different types of sustainability experiments. These spatial contexts differ along a variety of dimensions, but the detailed factors and patterns as well as the differences across contexts need further exploration.

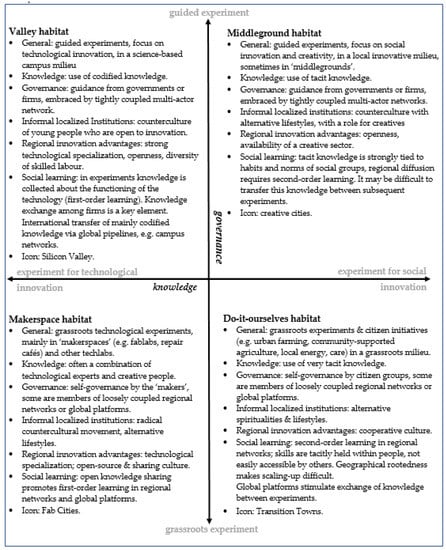

2.2. Synthesis: Archetypical Experimentation Patterns

In our conceptual framework we wish to capture the diversity of habitats in Europe, because this diversity has added value for transitions. These variations in cultures, institutions, political systems, networks, and capital stocks enable the promotion of, for example, new technologies, new lifestyles, and new policies [41]. Based on the current literature presented in Section 2.1, we construct archetypical experimentation patterns for the four habitats distinguished (Figure 2). These archetypes describe the typical mechanisms of experimentation. They are built up of five dimensions: the knowledge used, the governance applied, the supportive informal localized institutions, the regional innovation advantages, and the social learning dynamics. We also propose an iconic example for each habitat. It should be noted that these archetypes are used for analytical purposes. In reality, we expect to find mixed forms.

Figure 2.

Archetypical experimentation patterns in four habitats.

First, the Valley habitat is inspired by the iconic case of Silicon Valley, where technological innovations have developed in a science-based campus milieu. Regional innovation literature emphasizes the knowledge exchange among firms as a key element in the innovativeness of this milieu [42]. Knowledge exchange is stimulated by a high rate of labor mobility. This mobility generates professional networks and the dissemination of new knowledge [43].

Second, the Makerspace habitat is inspired by the numerous fab cities worldwide such as Barcelona and Toulouse, where technological grassroots experimentation is carried out in various ‘makerspaces’; these are fab labs, hackerspaces, repair cafés, and so on. The ‘makers’ are often part of a radical countercultural movement, which includes technological experts as well as creative people. This movement is striving to become more self-sufficient, which is why an open source and sharing culture is often promoted. A global platform supports knowledge exchange between fab labs worldwide [7].

Third, the Middleground habitat is presented as a favorable habitat for guided experiments for social innovation (although there may be other manifestations of this favorable habitat). The creative city is an iconic example. In a creative city, the middleground is a basic component of the local innovative milieu, where creatives (from the ‘underground’) and firms (from the ’upper-ground’) meet and interact in creative processes [44]. Florida [45] demonstrates how a counterculture (the ‘bohemians’) in this milieu correlates with an underlying openness to innovation and creativity.

Finally, the Do-it-ourselves habitat is presented as the favorable habitat for grassroots experiments and citizen initiatives for social innovation. At the moment, grassroots movements are developing in cities worldwide, such as the Transition Town movement, but are often deeply locally embedded in particular places. A basic component of this habitat is a countercultural milieu, characterized by alternative spiritualities and lifestyles [8].

3. Methodology

Our research question requires a deep analysis of experimentation patterns and spatial context factors in a few contrasting regional habitats in Europe. A comparative qualitative case study [46] is appropriate for this purpose. We wish to capture the diversity of habitats in Europe, to explore the dimensions that cause this contrast, and to find the diversity in factors that enable future upscaling. To this end, we selected four contrasting cases along the quadrants of our analytical framework. Each case consists of two elements, namely, a group of sustainability experiments and the corresponding habitat. For both elements, we selected a specific group of respondents: project leaders for the experiments and regional experts (i.e., experts who have an overall picture of the local and regional context of the experiments) for the habitat. A key issue in this research is how to anticipate future upscaling during experimentation. This was translated into interview questions about the actors’ expectations of future upscaling. The main steps in our research were (i) case selection; (ii) data collection (developing the questionnaire, interviews, action-oriented workshop); and (iii) data analysis to find the answers to the research question (interview analysis, document analysis).

3.1. Case Selection

We looked for four cases that can be considered as paradigmatic examples [47] of the archetypical experimentation patterns described in our conceptual framework (see Figure 2). The archetypes are developed using existing scientific paradigms grounded in the regional innovation systems and the transitions literature. We have used these paradigms for describing four of these patterns. In a methodological sense we may consider these patterns as a first attempt to develop an explanatory typology [48]. The empirical data of the comparative case analysis is then placed in the cells of this typology. Thus, we were able to compare the cases with the archetypes and give a first indication about the evidence and general applicability of these patterns (see Section 5).

The following three criteria were used for selecting the cases:

- The cases were expected to show a sharp mutual contrast. We were looking for cases that match the archetypes, and as such were expected to differ considerably on the dimensions identified in the framework.

- The cases were expected to differ from ‘the mainstream’ milieu. The innovative character of the experiments and habitat was an important criterion.

- We did not want to select radical cases, such as Masdar City, Arcosanti, and Damanhur. These cases are sometimes isolated from their context and disconnected from existing systems, making them neither adaptable nor adoptable [49,50].

We selected candidates for our cases from the literature, from sustainability conferences, and from websites. An additional practical criterion for selecting our cases was obtaining support from a regional expert who was willing to help us with the selection of the experiments and the respondents. Eventually, this selection process yielded four cases for this study, which were all located in a medium- or large-sized city, in European city regions.

3.2. Data Collection

3.2.1. Interviews

We developed interview questions for semistructured interviews with two groups of respondents, namely, the project leaders of experiments and regional experts. Some questions were similar for both groups, and some questions were specifically focused on one group. A detailed overview of the interview questions can be found in the Appendix A. For each case study, we interviewed 4–6 project leaders as well as 4–6 regional experts. We aimed to find the following regional experts for each case:

- a scientist in regional geography or economy;

- a regional policy advisor or politician;

- a local policy advisor or politician;

- a leader (or potential leader) of a local/regional sustainability network;

- an expert who has an overview of countercultures in the region.

The oral interviews lasted 60–90 min and were carried out by two researchers in 2016–2017. A detailed list of the 39 interviewees is presented in the Appendix A.

3.2.2. Action-Oriented Workshop

As we were aiming to conduct societally relevant research, we incorporated an action-oriented workshop in our research design. After finishing the interviews, we carried out a preliminary data analysis, and we then organized a group meeting with regional stakeholders (the interviewees and any other people willing to join). This meeting consisted of two parts. The first part was aimed at receiving feedback on our analysis and at checking both the validity and the reliability of our preliminary data analysis. The second part was aimed at discussing what regional stakeholders could do with the results, and how they could influence the habitat in a positive way. Also discussed were the next steps to be taken towards possible joint activities of respondents and other stakeholders and towards building or strengthening a regional sustainability network. The group discussions were led by one of the authors of this article, acting as a professional sustainability facilitator to support the discussion with the regional stakeholders. A detailed list of workshops and participants can be found in the Appendix A.

3.3. Data Analysis

We analyzed the interview results (see Table 1) and carried out a document analysis, using scientific reports, policy documents, folders, websites, and project visits as an additional source (see Appendix A).

Table 1.

How the interview questions are related to the dimensions in the archetypical experimentation patterns (see Figure 2 for the dimensions).

Respondents made various statements, qualifications, and judgements, for example, about the living conditions in the region and about the presence of countercultures. The statements were validated using triangulation (i.e., by comparing these statements with statements from other respondents and with additional documents), using iterative research steps (i.e., by asking feedback on the preliminary interview results in the action-oriented workshop; see Section 3.2), and by reflecting with the colleague interviewer about the interpretation of the interview results.

Finally, we compared the four cases. An important element in this comparison was the question whether the cases indeed showed a mutual contrast (as expected on the basis of case selection). We analyzed the diversity between the four city regions on two aspects: (i) the diversity in experimentation patterns and (ii) the diversity in the factors expected to enable future upscaling.

3.4. Description of the Cases

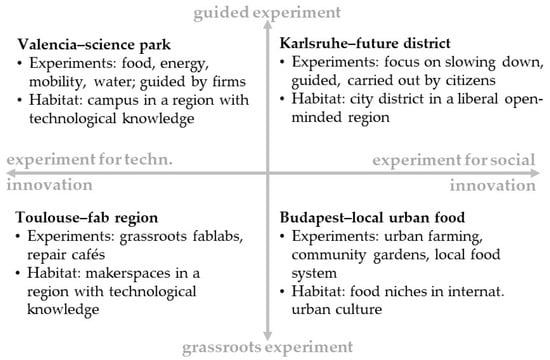

The four selected cases are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Summary of the selected cases.

Below, we give short descriptions of the four cases, including the experiments we selected in these cases.

- Case: Budapest—local urban food. In the city of Budapest, a group of grassroots creative niche experiments were started recently, focusing on sustainable food supply. We analysed experiments with urban farming, community gardens, a local food system, a food bank, and a responsible gastronomy initiative. Some of these may have been inspired by examples from other countries in Europe, but there is also a historical link with widespread kitchen gardens in Hungary in the past. At the moment, 36% of the Hungarian population still owns a kitchen garden [51]. The habitat in Budapest is special; it offers a number of supportive context factors, such as an urban culture and an international orientation. However, the grassroots experiments may face serious growth challenges in a traditional and defensive regime context.

- Case: Karlsruhe—future district. In the Oststadt district of Karlsruhe, a group of living lab experiments are carried out, focusing on the good life in the future. The ambition behind these experiments is that “we need time to get re-acquainted to ourselves and others, time to reflect on our behaviour and the impacts of that” [52]. The projects are focused on slowing down (i.e., to live in a more relaxed way) and community building. We analysed experiments with second-hand clothing, creative workshops, beekeeping, and district meetings aimed at reducing loneliness. The projects ran from July 2016 until March 2017 and were guided by the university and funded by the regional government. The habitat in Karlsruhe is interesting; in the past, many neighbourhood activities had been organized in this habitat, such as neighbourhood picnics. The regional context is formed by a prosperous region with a structural change towards science and innovation, and a growing creative class [53]. The region has a culture of liberality, open-mindedness, and willingness to experiment.

- Case: Valencia—science park. In Valencia, many sustainability experiments are carried out, often in a living lab setting. We analysed experiments with food (biological food in a hospital), energy (an ICT solution for saving energy), mobility (a sharing system for electrical cars), and water (water-saving technology). Experiments are governed by a hospital, a firm, the campus organization, and a technological R&D institute. The experiments are carried out in a campus milieu, often with strong links to the universities. The experiments are rooted in the technological specialization of the region, which has a culture of people willing to take risks.

- Case Toulouse—fab region. In the city region of Toulouse, there is a remarkable concentration of makerspaces. We analysed two repair cafés, two experiments in fab labs, and one in a hackerspace. The results of the experiments could be transferred to incubators and firms. There are about 25 incubators and accelerators in the region, many with a technological focus. The makerspaces have a strong community and the people involved have a general sustainability ambition, which is sometimes reflected in the experiments. The experiments are carried out by citizens. The regional conditions of Toulouse seem to be very well suited: there is a strong technological specialization in the region and a culture of open-mindedness.

4. Results

4.1. Budapest—Local Urban Food

In the Budapest region, many grassroots food initiatives have been started in the past few years, such as initiatives for regionalized food systems, urban farming, urban gardening, responsible gastronomy, and Food Banks. These initiatives are rooted in a deeper underlying food awareness, possibly in historical Hungarian gardening systems [51]. In the last decade of the 20th century, many of the kitchen gardens disappeared; they were ‘killed by the supermarkets’ (interview no. 1.1). Since 2004, this food awareness has been growing in strength again, which can be observed in the growing interest of certain groups of citizens in sustainable food (healthy, organic, zero-waste, regional, solidary, and transparent). This increased food awareness and the new initiatives for regionalized food systems may be able to ‘revitalize the historical kitchen garden system’ (interview no. 1.4). Issues of trust and mistrust are often discussed. In the new localized food systems, people like to restore ‘trust in the future, trust in clean and safe food, trust in the production system and trust in the farmer’ (interview no. 1.10).

The type of knowledge involved in the habitat of the experiments analyzed varies from tacit (e.g., regarding the organizational aspects of a community gardens and a food bank project) to codified (e.g., in urban farming technologies). The habitat may contain localized knowledge about the historical Hungarian gardening systems.

The type of governance in the habitat of the projects is grassroots; the projects are carried out by citizens and by social entrepreneurs. There is no governance for these initiatives from the government. The political support for grassroots food initiatives was recently strongly reduced (interview no. 1.1). The people involved in the projects have not yet formed a network.

Regarding the informal localized institutions, we observe that one of the groups involved in sustainable food is a countercultural group of urban, young, open-minded, creative people ‘with a lot of hope’ (interview no. 1.1). The general feeling in this group is, ‘yeah, I will be part of something, I will support the movement, the higher aims and values’ (interview no. 1.3).

In our respondents’ view, Budapest has some regional innovation advantages for regional expansion and the international replication of grassroots food experiments. Budapest is a Hungarian food hub, there is a large food awareness and an urban culture, and there are international influences such as from multinational companies (interview no. 1.7), foreigners, and tourists. These people can bring ‘fresh views’ (interview no. 1.2).

Social learning occurs and is needed at various levels. Respondents indicate that learning takes place on the level of individuals engaged in an initiative, on the level of the initiative, and between food initiatives in the region.

According to the interviewees, the most important factors expected to enable future upscaling of the initiatives are (i) the availability of funding; (ii) trust; (iii) recognized good examples; (iv) room for experimentation; and (v) a regional platform or network. Most of these factors are regional habitat factors. The interviewees indicate that it is possible to influence the factors in a positive way, stating that this improvement can often be achieved by the regional stakeholders themselves.

In the final workshop, possible next steps were discussed. The participants concluded that it is very important to create a sectoral platform or network where the people from various food-related initiatives can meet and exchange knowledge and ideas. Moreover, such a platform can foster the upscaling of different initiatives, and it can facilitate the development of hubs and training. The role of the platform is to engage partners, to execute experiments in pilot projects, and to develop regional, national, and international networks.

4.2. Karlsruhe—Future District

In the Karlsruhe region, many sustainability initiatives have been carried out, for instance, in urban gardening, fair trade, energy production, sharing, recycling, and repairing. The region has evolved from a ‘civil servant’ region (interview no. 2.7) into a region with science and innovation. In the Oststadt district, the creative class started to grow from around 2005 (interview no. 2.1); this may be related to the renovation of an old industrial area into a creative district.

The type of knowledge involved in the habitat of the selected projects is tacit knowledge, which is mostly related to organizational issues and ways to motivate citizens to join the initiatives: ‘We learned a lot, especially how to organize such a project’ (interview no. 2.5).

The type of governance is guided, with grassroots elements. Some guidance and support for these projects has been given by both the university and the government. Generally, there is strong political support for sustainability initiatives. The coordinator of the university supports the citizen groups by providing infrastructure, a meeting place, an existing network, public relations, funding, and legitimization. Within a set framework, the citizen groups are free to develop their initiative. The university forms a network with the various initiatives and creates a learning environment.

Regarding the informal localized institutions, the respondents indicate that the traditional values are still there, but a new counterculture is emerging. Elements of this counterculture include community building, sharing goods, spending time with friends, social entrepreneurship, societal awareness, and an aversion to technology and ICT. ‘Technological development is crazy; Internet, TV, …. This is not the way we would like to live. We would like to go back to personal contact’ (interview no. 2.5). The counterculture is searching for a new lifestyle, but they are not considered radical: ‘They are not rebellious, but they are innovative’ (interview no. 2.7). This counterculture consists mostly of young, creative people, including artists and students.

The region offers various regional innovation advantages for these experiments. It is a prosperous region with high education levels and a high quality of life. The people are interested in living in a ‘green public space’ (interview no. 2.7). There is a supportive general regional culture; several respondents emphasize the mentality of the region (Baden-Württemberg, Germany). Elements of this culture include a liberal, open-minded, pragmatic, and solidary attitude, as well as a willingness to experiment.

Regarding social learning, several respondents indicate that learning is needed in every project. The involvement of the university generates learning between projects, for example, by organizing project evaluations and network discussions. Some important learning challenges include learning how to involve more participants in the projects and learning how to take more risk.

According to the interviewees, the most important factors expected to enable future upscaling of the initiatives are (i) room for experimentation; (ii) funding; (iii) regional networks; (iv) motivation; (v) political will; and (vi) leadership. These factors are a mix of project-internal and regional habitat factors. The interviewees indicated that the project-internal factors (such as motivation and perseverance) are often difficult to influence in a positive way. These factors are closely connected to individuals. However, the interviewees stated that the habitat factors can be influenced, mostly by regional stakeholders.

In the final workshop, the possible next steps were discussed. Many suggestions were made for future improvement of the habitat. The participants of the workshop discussed project-internal factors such as personal development (e.g., being tolerant, developing leadership, taking risks, and trusting that the projects will continue). The following suggestions were made for improving the habitat factors: making it more attractive to learn from projects, connecting with other projects in other groups in the city, and mobilizing more political support. In the group meeting there was a common opinion that it is important to develop more attractive projects, so that more people will be involved.

4.3. Valencia—Science Park

In the Valencia region, many technological sustainability experiments have been carried out, for instance, in food (e.g., biological agriculture), energy (e.g., ICT and technology), mobility (e.g., electrical vehicles), circular economy (e.g., plastics), and water (e.g., water savings). Since 1980, many technological institutes have been created to promote innovation. Agro-food is still a strong sector, and the energy, health, and creative sectors are emerging sectors. In 2015, a political change resulted in more support for sustainability.

The type of knowledge involved in the habitat of the selected projects is mainly highly specialized technological and codifiable knowledge originating from the universities and the R&D institutes, with a few tacit and social innovation elements (for example, in the behavioral aspects of an experiment with a sharing system for electrical cars).

The type of governance is guided. The experiments are governed by a hospital, a firm, the government, and a technological R&D institute. The city vision supports these experiments and promotes the execution of experiments in living labs. There are several regional sectoral networks.

Regarding the informal localized institutions, the interviewees state that the local/regional counterculture plays an important role in sustainability experimentation. It consists of groups of young people with a strong community feeling and an interest in social relations. Some respondents mention other characteristics (i.e., open-mindedness and willingness to take risks); others see these elements as a part of the general regional (or even Mediterranean) culture. The respondents do not consider the counterculture radical.

The interviewees indicate that the region offers a few regional innovation advantages for these experiments. One respondent indicates that ‘the living conditions, for instance the Mediterranean climate, are excellent. It is like California: this attracts innovators and talent’ (interview no. 3.1). The physical conditions for experimentation are good. The region has two universities and various technological R&D institutes. At the universities, the ‘international students bring new ideas and innovations’ (interview no. 3.5). Several respondents indicate that the region has an open-minded and entrepreneurial culture; people are not afraid of failure.

Regarding social learning, it is stated that ‘learning is everywhere’ (interview no. 3.3), both first- and second-order learning. Learning by doing is the favorite learning style. ‘Learning by doing is part of the Valencian mentality; we just try!’ (interview no. 3.4). For future upscaling to succeed, respondents indicate that it is necessary to exchange learning experiences with other projects.

According to the interviewees, the most important factors expected to enable future upscaling of the initiatives are (i) funding; (ii) vision and political will; (iii) socio-cultural factors (community feeling, open-mindedness, willingness to take risks); (iv) entrepreneurship; (v) regional networks; and (vi) marketing. These factors are a mixture of project-internal and regional habitat factors. Respondents indicate that the project-internal factors (e.g., entrepreneurship) are difficult to influence in a positive way; these factors are closely connected to individuals. However, the interviewees indicate that the habitat factors can be influenced, often by the regional stakeholders themselves.

There was no interest in joining a final workshop, although in the interviews it was stated that ‘collaboration in quadruple helix networks was important’ (interview no. 3.1) and that there is a ‘wish to exchange experiences in regional networks’ (interview no. 3.7). It is not clear why the respondents were not interested in a workshop. We received feedback on our preliminary findings in a meeting with young regional experts in energy and climate change innovations. They also discussed additional ways to influence the habitat factors in a positive way, for example, by searching for additional funding sources, by branding Valencia as a living lab, and by stimulating curiosity in children to promote learning from experiments.

4.4. Toulouse—Fab Region

In the Toulouse region, many grassroots technological experiments have been carried out, for instance in approximately 35 fab labs, various repair cafés, a hackerspace, ICT associations, and electronics associations. The experiments are probably rooted in a long history of manufacturing industry in the region, and in a century of aeronautics industry. At the moment, the aeronautics and aerospace industries are a very important sector in the region. The region shows higher economic prosperity and employment growth than the average in France. The type of knowledge involved in the habitat of the selected projects is highly specialized technological codifiable knowledge, such as computer coding for a 3D printer or a laser cutter, in combination with creativity and design knowledge. This knowledge is widely available in the habitat. In the repair cafés, tacit knowledge is also involved.

The type of governance is grassroots. The habitat is characterized by self-governance by the ‘makers’. However, the fab labs are a member of a regional federation and of a global platform. The global platform provides strict guidelines for the projects. The ‘makers’ want to be free to develop their innovations, without requirements or guidelines from funders. As one interviewee put it, ‘we need a Maecenas!’ (interview no. 4.8).

Regarding the informal localized institutions, respondents state that the region has a large countercultural movement. In the city alone, there are around 270 alternative associations. Important values of this group include being against overconsumption, being self-sufficient, showing resistance, and employing guerrilla tactics. ‘We put up resistance against … everything; this goes back centuries’ (interview no. 4.10). The members of this movement meet at a yearly festival, which has about 35,000 visitors. Part of this movement is the fab lab community. The ‘makers’ appreciate this community, stating that ‘the atmosphere here in the fab lab is helpful. It is about the community feeling, the creativity, the absence of competition and the commitment’ (interview no. 4.5).

The region has various regional innovation advantages to offer for sustainability experiments; the Mediterranean climate is an important asset. The people show a strong social and environmental awareness. In addition, the region has a strong position in scientific engineering, in combination with creativity. This creativity is visible from the presence of artists and from an architectural and design school. A majority of the interviewees emphasize that there is a supportive general culture of open-mindedness, curiosity, and tolerance: ‘Usually people say “not in my backyard”. But in Toulouse the backyards are big!’ (interview no. 4.8).

Regarding social learning, the interviewees state that a new way of learning has recently emerged, which is about sharing knowledge, learning by doing, and being allowed to make mistakes. The government has formulated an ambitious open innovation and open source strategy for the region. ‘Toulouse wants to develop a model for the cooperative city in 2030’ (interview no. 4.13). ‘The region wants to be transparent. Everything should be open-source’ (interview no. 4.10).

According to the interviewees, the most important factors expected to enable future upscaling of the initiatives are (i) the community feeling of the ‘makers’; (ii) documentation and tools in the fab lab; (iii) regional networks; (iv) regional knowledge and skills; (v) funding; and (vi) communication. These factors are a mixture of project-internal and regional habitat factors. Respondents indicate that all the factors can be influenced in a positive way, often by the regional stakeholders.

In the final workshop it was concluded that the regional stakeholders (the makers, managers, coordinators, and politicians) do not yet have a coherent vision about the importance of fab labs for the makers themselves and for society at large. There is uncertainty whether fab labs are about having a good time while in the process of the ‘making’, or whether it is also about developing prototypes for the economic and sustainable development of the region and beyond. Important ingredients of a coherent vision about the fab labs might include the further development of a strong community feeling of sharing and collaboration, and the improvement in the conditions for transferring ideas and prototypes from the fab labs to elsewhere (i.e., other fab labs, incubators, and companies), for example, by keeping good documentation and by professionalizing the external communication.

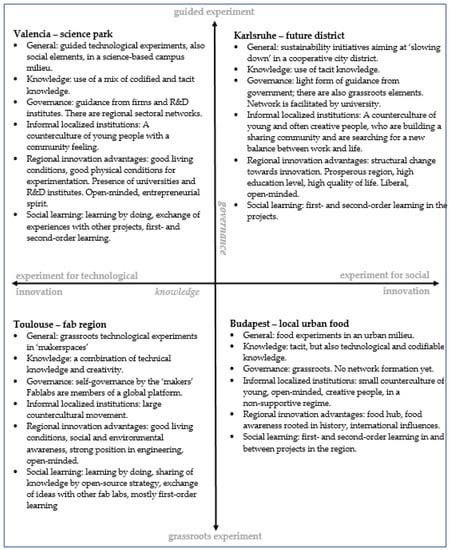

4.5. Comparison of the Four City Regions

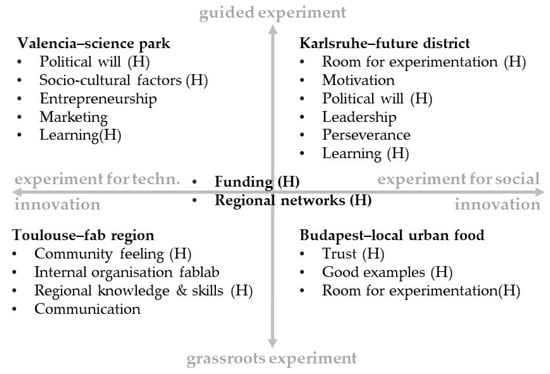

In Figure 4, the four cases in the four city regions are compared regarding the five dimensions of the archetypical experimentation patterns. Figure 5 shows a comparison of the factors expected to enable future upscaling.

Figure 4.

A comparison of the experimentation patterns in the case study results. The framework is identical to the one in Figure 2.

Figure 5.

Factors expected to enable future upscaling in the four cases. ‘H’ indicates that this factor is considered a habitat factor. (The respondents gave additional information about the factors during the interviews. We used this information to distinguish habitat factors from project-internal factors.) Factors mentioned by ≥30% of the respondents are presented here.

When comparing the experimentation patterns in the case study results, we find the following interesting similarities and differences:

- In general, we observe that the five analytical dimensions of the constructed archetypical experimentation patterns (see Figure 2) have explanatory power for the diversity between the cases. However, elements of other archetypes are also visible in the cases. Such a mixture is, for instance, visible in the Karlsruhe—future district case (in which the governance is mainly guided but also has grassroots elements) and in the Valencia—science park case (which deals mainly with technological innovation but also has some elements of social innovation).

- The role of countercultures is worth noting; these are very important in all four cases. Apparently, they play a crucial role in experimentation and future scaling, for instance, as pioneer users, participants, or stakeholders. The importance of pioneer users of innovations has been described by Rogers [54], who mentions the early adopters as an important user group and an integrated part of the local social system. In our research, the characteristics of the countercultures in the four cases are clearly different. In the upper quadrants, the countercultures mostly comprise young people, for whom community building is important, and who are searching for a new lifestyle. In the lower quadrants, and especially in Toulouse, the counterculture has a more radical character; it shows a stronger resistance against the mainstream.

- In all the cases examined in this research, respondents emphasize creativity and open-mindedness as important cultural factors; creativity is not reserved for the ‘middleground’ habitat. This finding refers to the work of Florida [45], who shows that creativity and openness to innovation correlates with a specific subculture. In a few cases, these factors are not limited to the counterculture but are rather a characteristic of the general regional culture. The regional innovation advantages are important in each of the cases. In three cases, the respondents underscore the good living conditions as important; in Valencia it was added that ‘these conditions attract innovators and talent’. This was also recognized by Moulaert and Mehmood [15], who mention the natural environment as an important part of an innovative milieu. There is a contrast in regional innovation advantages between the upper and lower quadrants. In the upper quadrants, the education levels and presence of knowledge institutes are emphasized, whereas in the lower quadrants, a social and environmental awareness is underlined. This awareness in the grassroots habitats is also emphasized by Seyfang and Smith [26]; they show that people’s motivation for grassroots action is based upon different values from the mainstream, for example, by a bottom-up generation of alternative systems of provision.

- In every case there is a strong awareness that learning is an important factor in sustainability experimentation. Learning by doing is the favorite learning style in the two quadrants on the left-hand side. In the quadrants on the right-hand side, no favorite learning style was indicated. Overall, we see that stakeholders are primarily interested in exchanging knowledge, ideas, and experiences. This knowledge exchange can be classified as first-order learning. The interviewees do not mention second-order learning explicitly, although we observe some second-order learning in the quadrants on the right-hand side. Social learning was not directly addressed by the respondents; however, we observed a social learning process in the final workshops in the four cases. Indications of social learning were addressed in expressions such as “it is important to create a sectoral platform or network” (in the Budapest—local urban food case) and “it is important to develop more attractive projects” (in the Karlsruhe—future district case).

Figure 5 presents a comparison between the factors expected to enable future upscaling. There is a wide variety of factors. We observe a mixture of project-internal factors and habitat factors, as well as a substantial contrast between the four habitats.

In every case, the interviewees emphasize the habitat factors ‘funding’ and ‘regional networks’. For funding, it is indicated that it is necessary to have better access to public and private funds. For regional networks, there is a clear difference between the upper and the lower quadrants. In the upper quadrants, it is indicated that it is vital to build multi-actor networks with a shared vision. A tightly coupled network [36] may promote the sharing of a vision. In the lower quadrants, the people involved in grassroots experiments are interested in being members of regional or global platforms. The links between members of these platforms are loose; they serve primarily for the exchange of knowledge between similar experiments.

5. Discussion

The main aim of this research was to explore the dimensions of contrasting regional habitats for sustainability experimentation in Europe. The main finding is that the five dimensions offer explanatory power for the diversity in factors expected to enable future upscaling. With the five dimensions we were able to construct four archetypical experimentation patterns. The empirical work has shown that the four cases belonging to these patterns each have specific factors expected to enable future upscaling.

The first point for discussion is a reflection on the ability to influence the habitat factors, i.e., the factors expected to enable future upscaling. From Figure 5 it may be assumed that the ability to influence these factors is varied. Most of the factors, such as funding, room for experimentation, and regional networks, may be relatively easy to influence by the regional stakeholders (e.g., by the government) in the short term. This was also confirmed by the interviewees. However, some other factors, such as the regional knowledge and skills and the regional cultural factors may refer to localized assets and capabilities which are difficult to influence [21]. In the TIM literature, it is indicated that these elements depend on socio-economic and socio-political history [16]. The respondents are more optimistic about this ability to influence these assets and capabilities than what is expressed in the existing literature.

The second point for discussion is the general applicability of the results. The findings of this research are based on four cases in four city regions in Europe. When comparing these findings with the developed archetypical experimentation patterns, we have two remarks. First, we observe that the analytical contrast between the archetypes is less visible in the cases. The cases often represent mixed forms of the archetypes. With regard to the regional innovation advantages, we observe a large variety of factors mentioned in the cases. Some of them were included in the archetypes, but a lot of them are not, such as the living conditions. Second, we may conclude that each case is an example of a larger family of similar European habitats. We may even assume that other European habitats can be plotted in the analytical space that is spanned by the four cases. It would then be possible to find the factors for future upscaling for another habitat by interpolating between the four cases in this research. However, great caution is required here. This research has also made clear that regions may possess very distinct and unique dimensions of spatial context factors, which are of crucial importance to future upscaling. For example, there are regions with a pronounced economic specialization (such as the aeronautics industry in the Toulouse region) or regions with a defensive regime context towards certain sustainability experiments (such as the Budapest region). Furthermore, it should be noted that we have analyzed regions which contain a medium-sized or a large city; the situation in rural areas may well be very different.

The third point for discussion is the relationship between habitats and regions. In our earlier work we suggested that various habitats may overlap in a geographical sense [11]. In this research there were also some indications that a city region may host several habitats, and this may have important policy consequences. This research shows that regional stakeholders are able to influence the majority of habitat factors in a positive way. An important policy decision on a city level would, for instance, be the choice between promoting learning between firms and research institutes in a science park, or promoting community learning in a grassroots milieu. This research may help to make explicit decisions in such matters.

The fourth point for discussion is the importance of the maturity of the habitat. When we reflect on the habitat concept from a systems perspective, we could argue that it is not only important that the individual factors are present, but also that the factors are present in combination with one another and that the factors can mutually reinforce each other. The presence of these factors in combination can make the habitat more mature. Sekulova [14] indicates that the quality of the mutual relatedness of the factors (e.g., values, counterculture, a nonrestrictive regime) is relevant for creating a ‘fertile soil’ for grassroots initiatives. In fact, our findings show some indications regarding the maturity of the habitat. In Budapest—local urban food we observe a few motivated individuals experimenting with innovations, in a period with recent socio-political changes. There is food awareness, but common values are not yet explicit. The counterculture is very small, and a network has not yet been formed. There is no environment for learning between projects, and there is no supportive urban or regional vision. In Karlsruhe—future district, what we see is different. We observe a large group of motivated citizens, a history of several years of grassroots initiatives in the district, common underlying values, participation by a countercultural group, an existing district network, an environment where learning between projects is stimulated, and supportive urban policies. We may therefore conclude that the habitat of Karlsruhe—future district is more mature than Budapest—local urban food, and that this maturity is the result of the combination of various habitat factors, including a history of several years of experimentation which may have improved the habitat in a co-evolutionary way. As one of the interviewees said, ‘Karlsruhe has created a good habitat in the past years, and at the moment it is very good’ (interview no. 2.4).

6. Conclusions

In this study, we had the following research questions: which spatial context factors enable the future upscaling of sustainability experiments in contrasting regional habitats in Europe, and is it possible to influence these factors in a positive way? The main conclusions are as follows:

- Funding and regional networks are important factors enabling future upscaling in every habitat.

- Every habitat has its additional distinct factors which enable future upscaling.

- This study suggests that it is possible to influence the majority of the habitat factors enabling future upscaling in a positive way, such as funding, room for experimentation, and regional networks. However, some important other factors, such as regional knowledge and skills have a path-dependent nature; as they are rooted in the socio-economic history of the region, they are not easy to improve in the short term.

In this study, we address gaps in our understanding of how different spatial contexts facilitate different types of sustainability experiments, or, in other words, how geography matters. We have developed four archetypes of these contexts and have identified distinct context factors. However, our analysis contains only four cases, with specific themes (urban food, slowing down, technological experiments on a campus, and makerspace experiments). It may be possible that other sustainability themes require different context factors.

Our findings are consistent with previous findings in the transitions and regional innovation literature, although some factors are found to be understated in the literature (e.g., the presence of a counterculture and the importance of regional living conditions). We observe that the analytical contrast between the theoretical archetypes is less visible in the real world. Social learning is regarded as a key process in sustainability experimentation in the literature, and in practice we have observed that the respondents are aware of the importance of learning; however, they do not yet have an articulated opinion on the various forms of learning (e.g., first- versus second-order learning and social learning in groups) and the factors enabling learning. We have, however, observed social learning processes in the group meetings.

The findings of this research allow us to give some practical policy recommendations:

- We observe that nowadays policymakers are very interested in developing their own city or region into a copy of an iconic successful example, such as a ‘Silicon Valley’, a ‘creative city’, or a ‘smart city’. This aspiration often goes hand in hand with a form of experimental governance to test innovations. This study has shown that there is a wide diversity in city regions. As a result, each city region may have its own specific context factors which enable these experiments. When making a future sustainability vision, we recommend for local and regional policymakers to anchor this vision in an analysis of the distinct available and necessary context factors. The method developed here may be useful for that analysis.

- An important finding of this research is that the majority of the habitat factors enabling future upscaling can be influenced in a positive way, mostly by the regional stakeholders. This insight may have empowered the group of interviewees and motivated them to think about future joint actions. Our policy recommendation is to support these discussions, and to stimulate the formation or further expansion of a multi-actor sustainability network or platform. These networks may enable experimentation towards future upscaling.

This study provides one of the first attempts to systematically analyze the spatial context factors enabling the future upscaling of sustainability experiments. We have found evidence that in experimentation processes, the geography matters. We are convinced that more research is needed, for instance, research including more case studies with different sustainability themes and different contexts, such as rural areas. It would also be valuable to analyze more cases with a defensive regime context, as these situations may require a specific approach. A second item for future research is the upscaling dimension. The four regions in this study not only have various context factors for experimentation, but also have different conditions for future upscaling. An important question for further research is which localized factors are needed for the actual diffusion and translation of sustainability experiments. We recommend that this question be answered in future research.

Author Contributions

H.v.d.H. proposed the research, carried out the data collection and the analysis and wrote the paper. J.S. helped with the data collection. G.H. helped with the methodology. G.H., M.H., R.R. and J.S. helped to streamline the argument.

Funding

This research was funded by the Provinces of Utrecht and Gelderland in The Netherlands.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the Provinces of Utrecht and Gelderland in The Netherlands, for their financial support for this research. In addition, we would like to thank two students from Utrecht University for their help. Finally, we would like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments on an earlier version of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Interview Questions, List of Interviewees, List of Workshops, Overview of Document Analysis

Interview Questions

We developed interview questions with two groups of respondents: project leaders of experiments and regional experts. Some questions were similar for both groups, and some questions were specifically focused on one group. This is indicated below. The following interview questions were asked:

- Trends (experts only). We asked the interviewees to indicate the important demographical, economic, and cultural trends in the context of the sustainability experiments in this region. We incorporated the analysis of trends in the interviews, as experimentation in cities and regions may be strongly influenced by global or national pressures and social interests [55] as part of the socio-technical landscapes in the multilevel perspective. Trends may result in change at the regime level, creating opportunities for experiments [56].

- Experiments in the region (experts only). We asked the interviewees which sustainability experiments were carried out in the region.

- Description of the experiment (project leaders only). We asked the interviewees what the experiment was about, what the respondent’s task was, and what the respondent aimed to achieve with this experiment.

- Factors expected to enable future upscaling (experts only). We asked the interviewees which factors were expected to enable future upscaling of the experiments in the region. Upscaling was translated into ‘growth’, to facilitate comprehension by the respondents. Some respondents asked for a clarification of this question. We explained that we define ‘growth’ as ‘obtaining more users and more projects’.

- Top five factors (project leaders only). We asked the interviewees to select the five most important factors that are expected to enable future upscaling for their project, and in what way these factors were important. Upscaling was translated into ‘growth’, to facilitate comprehension by the respondents. The respondents were asked to select the factors from a longlist of 15 factors.This longlist was built on our earlier research on habitats [11]. The longlist contained (i) the most important habitat factors from our earlier research [11]; (ii) the most important project-internal factors from our earlier research [11]; (iii) social learning factors; (iv) two general factors; and (v) a ‘wildcard’ factor (chosen by the respondent).Habitat factors were cooperation in regional networks, funding, room for experimentation, regional learning, match with regional vision/specialization, and regional knowledge and skills.Project-internal factors were user involvement, profitability, and technical quality of the innovation. Social learning factors were trust, commitment, and reframing (reframing was translated into ‘gaining new insights and perceptions’, to facilitate comprehension by the respondents). We used the social learning factors described by Sol et al. [38].We added two general factors: leadership and attitude towards risk. Leadership is often mentioned in both transition literature and entrepreneurship literature. The attitude towards risk is mentioned as a specific transformational leadership competence, focused on innovation [57].

- Can the enabling factors be influenced (project leaders only)? We asked whether these factors can be influenced in a positive way, and if so, by whom.

- Role of learning (both). We asked what the role of learning is in this process, e.g., is it needed to gain new insights.

- Regional advantages (both). We asked what makes this region special for these experiments, and whether this region is unique for these kinds of experiments in Europe.

List of Interviewees

Case: Budapest—Local Urban Food

| No. | Role and Type of Respondent | Date of Interview |

| 1.1 | Community gardens coordinator (project leader) | 3 November 2016 |

| 1.2 | Expert on food, abandoned spaces, and creativity (expert) | 4 November 2016 |

| 1.3 | Initiator of local food system (project leader) | 4 November 2016 |

| 1.4 | Expert in change agents in Hungary (expert) | 4 November 2016 |

| 1.5 | Responsible gastronomy volunteer (project leader) | 6 November 2016 |

| 1.6 | Foodbank project manager and trainer in agro-food (project leader) | 7 November 2016 |

| 1.7 | Urban farming pioneer (project leader) | 7 November 2016 |

| 1.8 | Local politician (expert) | 8 November 2016 |

| 1.9 | Agriculture researcher (expert) | 9 November 2016 |

| 1.10 | Local food systems researcher (expert) | 10 November 2016 |

Case: Karlsruhe—Future District

| No. | Role and Type of Respondent | Date of Interview |

| 2.1 | Team member of project on reducing loneliness (project leader) | 13 January 2017 |

| 2.2 | Initiator of project on second-hand clothing (project leader) | 14 January 2017 |

| 2.3 | Team member of project on beekeeping (project leader) | 14 January 2017 |

| 2.4 | Coordinator of local agenda 21/policy advisor of regional government (expert) | 2 May 2017 |

| 2.5 | Two initiators of project on creative workshops (project leader) | 3 May 2017 |

| 2.6 | Creative sector expert (expert) | 3 May 2017 |

| 2.7 | Three policy advisors of local government (expert) | 3 May 2017 |

| 2.8 | Coordinator of the future district projects (expert) | 4 May 2017 |

Case: Valencia—Science Park

| No. | Role and Type of Respondent | Date of Interview |

| 3.1 | Science park expert (expert) | 11 May 2017 |

| 3.2 | Team member of car sharing project (project leader) | 11 May 2017 |

| 3.3 | Business developer of ICT solutions for energy savings (project leader) | 11 May 2017 |

| 3.4 | Expert in international projects (expert) | 11 May 2017 |

| 3.5 | Expert in education for sustainability pioneers (expert) | 15 May 2017 |

| 3.6 | Two team members of biological food project (project leader) | 16 May 2017 |

| 3.7 | Two policy advisors of local government (expert) | 17 May 2017 |

| 3.8 | R&D manager in water savings technology (project leader) | 18 May 2017 |

Case: Toulouse—Fab Region

| No | Role and Type of Respondent | Date of Interview |

| 4.1 | Expert in makerspaces in Toulouse (expert) | 30 October 2017 |

| 4.2 | Fab lab manager (expert) | 30 October 2017 |

| 4.3 | Fab lab connector (expert) | 30 October 2017 |

| 4.4 | Researcher of regional economy in Toulouse (expert) | 31 October 2017 |

| 4.5 | Developer of creative prototype at fab lab (project leader) | 31 October 2017 |

| 4.6 | Advisor of repair café for bikes (project leader) | 31 October 2017 |

| 4.7 | Initiator of repair café (project leader) | 31 October 2017 |

| 4.8 | Developer of energy prototype at fab lab (project leader) | 1 November 2017 |

| 4.9 | Hackerspace developer (project leader) | 1 November 2017 |

| 4.10 | Former regional coordinator of fab labs (expert) | 2 November 2017 |

| 4.11 | Regional politician (expert) | 2 November 2017 |

| 4.12 | Fab lab coordinator and incubator (expert) | 2 November 2017 |

| 4.13 | Local politician (expert) | 2 November 2017 |

List of Workshops

| Case | Date | Location | Number of Participants |

| Budapest—local urban food | 11 November 2016 | Budapest | 7 |

| Karlsruhe—future district | 5 May 2017 | Karlsruhe | 8 |

| Valencia—science park | 19 May 2017 | Valencia | approx. 25 |

| Toulouse—fab region | 6 November 2017 | Toulouse | 10 |

Overview of Document Analysis

| Case | # of Documents Analysed | # of Websites Visited | # of Folders Analysed | # of Visits to Meetings |

| Budapest—local urban food | 2 | 3 | 1 | |

| Karlsruhe—future district | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Valencia—science park | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Toulouse—fab region | 3 | 2 | 1 |

References

- Geels, F.W. Technological transitions as evolutionary reconfiguration processes: A multi-level perspective and a case-study. Res. Policy 2002, 31, 1257–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potjer, S.; Hajer, M. Learning with cities, learning for cities. The Golden Opportunity of the Urban Agenda for the EU. Available online: https://www.uu.nl/sites/default/files/essay-urbanfuturesstudio-12juli-web.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2018).

- Evans, J. Trials and Tribulations: Problematizing the City through/as Urban Experimentation. Geogr. Compass 2016, 10, 429–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulkeley, H.; Castan Broto, V. Government by experiment? Global cities and the governing of climate change. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2013, 38, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendler, J. Grassroots experimentation: Alternative learning and innovation in the Prinzessinnengarten, Berlin. In The Experimental City; Evans, J., Karvonen, A., Raven, R., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 150–162. [Google Scholar]

- Monstadt, J. Urban governance and the transition of energy systems: Institutional change and shifting energy and climate policies in Berlin. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2007, 31, 326–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hielscher, S.; Smith, A.; Fressoli, M. WP4 Case Study Report: FabLabs; Report for the TRANSIT FP7 Project; SPRU, University of Sussex: Brighton, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Longhurst, N. Towards an “alternative” geography of innovation: Alternative milieu, socio-cognitive protection and sustainability experimentation. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2015, 17, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raven, R.; Sengers, F.; Spaeth, P.; Xie, L.; Cheshmehzangi, A.; de Jong, M. Urban experimentation and institutional arrangements. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2017, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T.; Coenen, L. The Geography of Sustainability Transitions: Review, Synthesis and Reflections on an Emergent Research Field. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2015, 17, 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Heiligenberg, H.A.R.M.; Heimeriks, G.J.; Hekkert, M.P.; van Oort, F.G. A habitat for sustainability experiments: Success factors for innovations in their local and regional contexts. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 169, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, A.J.; Raven, R.; Berkhout, F. Transnational linkages in sustainability experiments: A typology and the case of solar voltaic energy in India. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2015, 17, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimeriks, G.; Boschma, R. The path- and place-dependent nature of scientific knowledge production in biotech 1986–2008. J. Ecom. Geogr. 2014, 14, 339–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekulova, F.; Anguelovski, I.; Argüelles, L.; Conill, J. A ‘fertile soil’ for sustainability-related community initiatives: A new analytical framework. Environ. Plan. A 2017, 49, 2362–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulaert, F.; Mehmood, A. Analysing regional development and policy: A structural-realist approach. Reg. Stud. 2010, 44, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulaert, F.; Nussbaumer, J. The social region. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2005, 12, 44–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, R.; Schot, J.; Hoogma, R. Regime shifts to sustainability through processes of niche formation: The approach of strategic niche management. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 1998, 10, 175–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coenen, L.; Benneworth, P.; Truffer, B. Toward a spatial perspective on sustainability transitions. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 968–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]