1. Introduction

Because of the increasing number of cross-border cooperation (CBC) projects carried out along the borders of European territories in the past few decades [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5] and the considerable amount of people influenced by such initiatives [

6], the issue is gaining greater relevance. CBC has become not only a way to level the development of disadvantaged areas but also a way to utilize the competitive advantages of cities located on the borderlands of two countries. Thus, it is possible to say that they present dual potential and exceptional diversity, which they can use to obtain a synergistic effect of cooperation, leading to a stronger territorial cohesion.

The concept of territorial cohesion has been gaining increasing interest within academic and EU policy circles. The territorial dimension as a key topic in the EU political agenda is of great importance and, at the same time, it is important to answer several questions of the debate expressed in the Green Paper on Territorial Cohesion [

7]. At present, territorial cohesion may also mean (for example, in the White Paper on European Governance) the co-ordination of policies with an impact on one territory.

Regarding the more interventionist approach to spatial planning as well as sustainable development, there is a need for a spatial framework for community policies. Such a framework would resemble the European Spatial Development Perspective, but also form part of territorial cohesion policy, sharing responsibility of the Union and its member states [

8]. The new concept of territorial cohesion could mean a formal planning role for the European Union. It is also clear that territorial cohesion needs to be seen to contribute to the competitiveness of the European Union and its macro-regions [

9]. It should also benefit from competitive territorial advantages such as human capital, knowledge centers, decision-making structures, and accessibility of capital [

10]. Back in 2005, the European Commission provided an explanation that territorial cohesion had become a key element for promoting stronger integration of the territory of the Union in all its dimensions, and cohesion policy supported the balanced and sustainable development of the territory of the Union at the level of its macro-regions and reduced any barrier effects through cross-border cooperation (CBC) and the exchange of best practices [

11,

12]. Moreover, CBC includes direct relations between local governments (the most frequent, formal form), but it also extends gradually to many other entities, institutes, and organizations, and even enterprises from neighboring cities [

13,

14]. In fact, the mentioned multi-level governance is based on fundamental CBC dimensions. Within these dimensions, the following regions should be highlighted: intra-state; urban-rural; local-regional; and functional [

15]. Considering the complex process of joint planning, the “barrier effect” can be minimized through fostering opportunities for integrated territorial development or by establishing strategies that foresee the involvement of actors from different territorial levels aiming at a stronger vertical integration. The main goal of these types of cooperation is usually connected to individual needs and expectations of cross-border partners, but the most important relevance of CBC is the ability to solve common border problems, using synergistic resources and the potential of each partner.

CBC processes have a crucial importance in reducing all sorts of barrier effects on borderlands [

16]. Euroregions, in particular, play a big role in this process, creating networks that involve a wider range of local and regional actors into the CBC process, on both sides of the borders [

17].

A special kind of cooperation is frequently based on special European funds, such as the INTERREG-A program. It has a big impact on the reduction of the barrier effect along the border across five dimensions (institutional-urban, accessibility, culture-social, environmental-heritage and economy-technology) [

18].

Special cooperation opportunities can be identified in border cities. These cities are motivated and mobilized for cooperation through government policy, especially European Union (EU) priorities, as well as specific spatial conditions, e.g., roads, transport, and connectivity network [

19,

20,

21] among many others; also, there are additional opportunities coming from mutual use of trade and services of several types [

22,

23,

24]. Another reason is the close relationship between residents, organizations, and institutions, as well as entrepreneurs operating on both sides of the border [

25,

26,

27,

28]. Research results [

25,

29,

30] shows that CBC mostly is done through projects, but they are completed rather according to actual needs of partners. Rarely they are part of long-term cooperation plans. This approach means that the potential for CBC in border cities is not fully exploited; the lack of leadership that would point out the main directions of the CBC may explain that. These directions should be beneficial both for the border cities as well as for other actors of CBC strategies and projects on both sides, creating so-called win-win situations. Thus, they should also result from a well-thought-out CBC strategy, developed jointly by border cities and their audiences.

Also, and considering recent research regarding CBC projects and strategies, several disparities have been identified among CBC projects and their results [

2,

21,

31,

32,

33,

34], among many other studies and pieces of research regarding not only their relevance to influence positively their populations, but also to achieve sustainability. Some cross-border regions may provide innovative platforms for multidimensional integration processes, which are needed to achieve more sustainable life standards. As territorial integration processes are occurring on a regional level, some activities can be labeled as “cross-border region building” and “territorial integration processes”. It is necessary to answer what this means for the search for better policies and strategies. The opportunities that are created by cross-border cooperation will be highlighted. That is why, for sustainable CBC development, it is necessary to use sustainable planning [

35]. One sustainable planning tool, especially on borderlands, is a strategy including the cross-border alliances of cities and cross-border alliances of various entities on the municipal level [

36]. Specific planning strategies can be used, among others, to foster a coordinated approach towards a sustainable regional planning to improve connectivity and the movement between cities, regarding accessibility and transportation, infrastructure, and services, developing common master plans, and a strong political commitment towards the CBC project. However, considering the large possibility of methods and sustainable planning approaches towards the success of CBC projects, each case needs to be deeply analyzed to define specific planning.

In this regard, the research problem concerns the strategic planning of CBC at the level of border cities. Although CBC is dynamically developing, among others in the EU, this process is visible mainly at the level of Euroregions, and rarely at the level of cities. The role of the cross-border environment in tightening CBC at the city level is poorly recognized. The border cities should cooperate not only with local authorities but also through other target groups, e.g., NGOs and entrepreneurs. It is not easy to formalize and agree CBC priorities with target groups. This process should also consider the aspects of sustainable development and sustainable planning in the social, economic, and environmental dimensions. Few border cities have formalized bilateral cooperation strategies; even fewer cities have formulated strategies that consider the CBC of different target groups in a cross-border, sustainable environment.

Contextually, the study aims to define the main stages of CBC strategy development, and the dedicated cooperation of border cities. This paper identifies the main stages of the strategy building process for the cross-border alliance of border cities. Strategic alliances are a form of network relations and can be strong impulses for a long-lasting process of transforming border cities into cross-border cities. Alliances are formalized or informal forms of inter-organizational relationships. In creating a strategic alliance, an important role is played by similarity and complementarity of the organization, common skills, and specific knowledge of each of the partners. Cross-border environment factors that significantly determine CBC will also be indicated as well as pivotal actors in this process. These problems are described in several parts of the paper. The paper also shows the key activities related to the transformation of the cross-border bilateral alliance into a cross-border network alliance. In this way the authors identify the fertile areas to develop sustainable CBC projects. This approach is also based on other issues [

3,

14].

The research problem will be solved and the goal of the issue will be achieved by research regarding CBC in the border cities of Cieszyn (PL—Poland) and Cesky Tesin (CR—Czech Republic), which are going to develop the CBC strategy. In fact, the border cities of Cieszyn and Cesky Tesin have been involved, since 1998, with a CBC territorial strategy, namely the Euro-Region Cieszyn Silesia (MOT, 2016).

Thus, qualitative research has been conducted, in the form of literature review and surveys using two data collection methods: computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI); and computer-assisted web interview (CAWI). To perform the present study, the authors used research with 55 respondents from Cieszyn (30) and Cesky Tesin (25), representatives of local authorities, public and private institutions, non-government organizations, and entrepreneurs from the both cities. The authors also used a case study research (CSR) method and analyzed CBC of the two border cities. Based on the cross-border research results, in the next section the authors identify the key areas of possible alliances of the border cities of Cieszyn and Cesky Tesin. They also indicate the main stages necessary to create a CBC strategy for cross-border alliance of border cities. In the next section the authors present a model of sustainable development of cross-border, inter-organizational cooperation and define the key activities related to the transformation of the cross-border bilateral alliance into a cross-border network alliance. Moreover, the main conditions for the development of network cooperation in the frame of well-prepared CBC strategy for border cities have also been pointed out. As mentioned before, there are not many examples of such strategies for border cities, which is why this issue should be helpful for border cities that want to develop CBC as a way for sustainable development of borderlands.

2. The Role of the Sustainable Planning in the Development of Border Areas

The critical role played by sustainable planning in the success of territories, projects, and strategies—and their long-term sustained development and growth—as well as to achieve the desired sustainable cities is well known [

37,

38,

39]. The strategies can be regarded as a type of cross-border planning mechanism in promoting territorial development of the border region. These strategies include key aspects of spatial planning as well as some social and economic dimensions. CBC projects can be favorable to the implementation of a genuine and long-term cross-border spatial plan, with the goal of reducing the barrier effect and improving the territorial capital along the cross-border region. It also supports the territorial development across the border area. Consequently, cross-border planning, cross border strategies and governance structures should be confined to promoting the active involvement and mobilization of local and regional actors in the cross-border cooperation process, and in implementing several cross-border projects of local/regional significance [

40].

One of the more difficult elements in cross-border planning for development lies in institutional cooperation. Most experts divide institutional cooperation into two prototypical models: formal (presidential meetings with memoranda of agreement, or interparliamentary negotiation); and informal (regular meetings among local and higher government authorities, as well as non-binding agreements to cooperate on local level). Formal accords can lead to permanent cross-border institutions, including decision-making bodies either with jurisdictionary or advisory status [

41].

The concept of sustainable development has as start point at the United Nations Conference regarding Environment and Development [

42], where the need to adopt new development strategies have been recognized at a local scale as at a global one. In fact, this need has been already identified in 1969 in a UNESCO study, which concluded that by 2000 the urban population will be only 15% [

43]. In 1993, a study of the World Bank highlighted 2010 as the year when most of the population will live in cities, leading to chaos for urban systems and dynamics, as well as to an increase in desertification issues and scarcity of resources in rural territories [

44].

Almost half a century later, the concept is still in discussion. Nevertheless, one of the most accepted definitions of Sustainable Development, according to experts [

45,

46,

47] is “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of the future to meet their own needs”. Furthermore, and considering the above, human needs should be satisfied along with the opportunity to achieve an acceptable standard of living to the existing population as well as to future generations [

47]. The previous criteria require an equitable distribution not only of the benefits from the consumer society, but also of their inherent risks. In fact, these goals go further than the key criteria for the decision-making process. Actually, mainly the cost-benefit-analysis (CBA) has been used, based on the market values, which is also applied to goods, environmental services and social care [

48,

49].

Moreover, the environmental dimension is clearly defined as the sum of all bio-geological processes and the elements involved in them [

45,

46]. Thus, it requires the preservation of the viability of ecological systems as the natural basis of sustaining human civilization [

39,

46].

Considering the institutional dimension, it is possible to verify that society groups, as well as legal operations, administrative services, and their main actors, are inserted on it [

38,

39]. From a sustainability perspective, a higher public participation, an equality of opportunities, an open society—regarding ethnics or gender—along with an administration not “overly corrupt”, are the desires [

26,

38]. These types of institutions and the synergies they create are pivotal for achieving sustainable development [

26,

33,

37,

38,

39].

Focusing on the economic dimension, defined on several occasions as a society-specific subsystem by their particular features—efficiency, short-term goals, and a personal perception by human beings as individuals in maximizing profits [

38,

39]—sustainability needs an economic system able to satisfy its citizens’ needs, offering employment opportunities and a higher resilience capacity, aiming to provide these features from a long-term perspective [

23,

28,

50,

51]. Thus, to face such challenges, the competitiveness of the economic system should be an integral part of the concept of sustainability [

38,

45,

46,

48].

In this regard, sustainability standards are scrutinized in the available literature as any science or humanity would be, with the following types of questions raised by experts (one such example is the Aral Sea disaster—unfortunately, one among many others [

45,

46,

50]): How much climate change is acceptable? What amount of unemployment should be tolerated? Answers to these questions define regulatory parameters for society’s future [

45,

46], and if a sustainability path is chosen, sustainable goals should be well defined as well as containing a strong and transparent political commitment [

26].

Based on the available literature, it is possible to verify that the concept of sustainability is considerer as a “maximum”, and its almost impossible to dissociate from any roundtable or political speech [

26].

In this regard, urban planning processes, as national as international or even in the specificity of a trans-boundary area, are not an exception. Here, CBC projects and strategies will play a critical role towards sustainability.

Thus, regarding CBC strategies and sustainable planning, the creation of the creation of the Schengen Area, in which five European States (Germany, Belgium, France, Luxemburg, and the Netherlands) decided to abolish checks at internal borders in 1985 [

38], should be highlighted. Commercial relationships between the sovereign territories proceeded smoothly [

22].

Also, cohesion policies carried out by the EU have been a major step towards the stability and increase in sustainability within European territories [

22,

26]. Development and territorial cooperation programs have been applied to neighboring countries by the Good Neighbor Association Tool (This strategy/tool has been co-funded by EFRD [

1]) [

1]. Nevertheless, there are new planning models for cities worldwide, increasing concerns regarding the need to rethink how cities will develop and cooperate between one another [

30,

52]. In this regard, land use policies have been considered an important tool to prevent uncontrolled urban sprawl, fostering sustainable development and revitalization [

53,

54].

Contextually, CBC projects and strategies are seen as the catalyst for this new era of planning and sustainability [

26]. In fact, several European CBC projects have been implemented and have demonstrated their positive results and impacts over border territories, such as the example of COORDSIG, PLANEXAL, GEOALEX, OTALEX, OTALEX II, OTALEX C—all CBC projects related to territorial governance and resources valorization in the Iberian Peninsula through the last few decades [

55].

There is the EU 2020 strategy, which states, according to the European Commission [

56] “the Europe 2020 strategy represents a reference framework for activities at EU and at national and regional levels for the current decade and puts forward three main priorities to make the EU a smarter, more sustainable and more inclusive economy and growth”, defining target areas to measure progress in meeting goals in EU Strategy 2020 [

27]. In the scope of this strategy, a set of indicators have been defined such as employment rate, investment on research and development (R&D), greenhouse gas emissions, share of renewable energy, energy efficiency, early leavers from education, tertiary educational attainment, and poverty and social exclusion, all of which should be seen as the new critical points to focus towards sustainable planning and growth, through CBC projects and strategies.

3. Methodological Approach

To achieve the aim of the paper, the authors have used studies and empirical research—both qualitative and exploratory—serving to better identify the problem and understand its essence. The research was conducted in the years 2017 and 2018. Study works consisted primarily of an analysis of the available literature regarding the cross-border alliance of Cieszyn and Czech Cieszyn. The authors used a case study research method and analyzed the cross-border alliance of two border cities: Cieszyn (PL) and Cesky Tesin (CR).

A case study is an attractive method of solving problems concerning network connections and international management [

57]. The case study is mainly used to analyze specific events or phenomena [

58,

59]. Its purpose may be exploration, description, and explanation [

60]. Although the basic disadvantage of this method can be considered the influence of many variables that cannot be controlled—and which interfere with the obtained results—this method gives the possibility of in-depth analysis of the problem (as opposed to quantitative methods). A correctly implemented case study can lead to exploratory conclusions, which is often the first step in the process of verifying or disproving the theory [

61].

The process of building a theory from a case study includes the following stages: selection of cases; definition of research instruments; data analysis; hypothesis modelling; literature studies; and closing the study [

62]. In the research process, it is particularly important to formulate research questions that may be descriptive, exploratory, or explanatory [

63]. It is also important to select a sample that can be random or intentional [

64]. Regarding the case study, randomness is not needed or even desirable, which is why targeted selection is used. Random selection is subordinated to the requirement of representativeness, whereas targeted selection, also called theoretical, omits the criterion of representativeness [

62]. The criteria for the assessment of the test sample do not consider the requirement of representativeness, but the criterion of saturation. It is not about verifying the degree of truth of the hypothesis under examination, but about making a theoretical proposal that reflects reality as truly as possible.

To solve the research problem concerning strategic planning of CBC at the level of border cities, an example of cooperation between Cieszyn and Czech Cieszyn was used. These cities have formed a strategic alliance for joint spatial development as well as social and economic revival of the areas on both sides of the border river Olza. The alliance was developed based on a jointly prepared planning document—The Strategy for the Development of the Olza River Waterfront in Cieszyn and Czech Cieszyn—which considered only some aspects of cooperation [

65]. Strategic alliances can initiate a long-lasting process of transforming border cities into cross-border cities. This should relate to the process of mutual compensation of resources, potentials, and spatial transformations of these areas to create a high-quality offering for residents and other target groups. To achieve this goal, the establishment of alliances in agglomerations by territorial self-governments and by cultural, research, business, and educational institutions as well as cooperation and collaboration between these local and regional actors is fundamental [

66,

67,

68]. Alliances can lead to the reduction of uncertainty and increase the flexibility of operation [

69]. The alliances relate mainly to specific thematic projects implemented in a bilateral or networked system, with the involvement of various actors. Nowadays, due to the occurrence of non-economic crises and increasing environmental problems, the alliance also includes sustainability competences related to the simultaneous implementation of economic, social, and environmental goals [

70].

There are some studies [

71,

72] where key issues for the study of alliances in cooperation projects have been identified, namely: the formation of alliances; the choice of governance structure; the dynamic evolution of alliances; the performance of alliances; and the performance consequences for organizations entering alliances. A case study includes all the above elements.

Based on the analysis of this material, a hypothesis was formulated, which was verified by further qualitative research: computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) and computer-assisted web interview (CAWI), based on electronic surveys which had been sent to respondents before the interviews. The survey is composed of closed, single and multiple-choice questions. The surveys also contained additional questions characterizing the respondents, including type of entity, time of engagement in cross-border cooperation, etc.

Quantitative research also covered local authorities—Cieszyn and Czech Cieszyn—together with other entities, which usually cooperate with them to form and develop the cross-border alliance e.g., public and private institutions as well as non-government organizations and entrepreneurs. Access to information was gained in two ways. Information about these entities was obtained directly from the cooperating cities, and the attendance lists from information meetings in which representatives of the respondents took part were investigated.

This research was done by interviews (30 Polish and 25 Czech respondents). The interview concerned, among others, the following issues: scale and duration of engagement in the cross-border alliance of Cieszyn and Czech Cieszyn; preparation for participation in this alliance; compliance of the alliance with its own objectives of cross-border cooperation at the level of Cieszyn and Czech Cieszyn; other potential areas of future alliances at the level of Cieszyn and Czech Cieszyn (priority and secondary areas) and forecasts for further development of these alliances; entities that should engage in such an alliance; expected results of future cross-border alliances; and the need to develop a comprehensive cross-border cooperation strategy based on alliances.

They took the form of computer-assisted telephone interviews (CATI) and computer-assisted web interviews (CAWI).

Due to the number of responses, the interviews were treated only as a numerical support for qualitative research because such small research samples should not be subjected to statistical treatment, due to the lack of representativeness for the assessment of the total population of entities. It is difficult to determine the real number of public and private bodies which operate in Cieszyn and Czech Cieszyn as, for example, some entities are active only formally; some of them periodically suspend their activity or they are simply not active.

Based on the analysis of project documentation and a case study, a research hypothesis was formulated, which was verified by the results of interviews. This hypothesis referred to the possibility of greater involvement in cross-border alliances of other, non-governmental, institutional entities, e.g., non-governmental organizations or entrepreneurs and the need to create a CBC strategy for both cities based on alliances in particular areas. At the same time, the authors sought to identify other areas of potential alliances of strategic border cities and to indicate the main stages of activities aimed at creating a strategy for cross-border cooperation between border cities based on alliances.

4. Case Study Results: Cieszyn and Czech Cieszyn

The case study concerns cooperation between two border cities: Cieszyn (Poland, Voivodeship of Silesia, municipality of Cieszyn) and Český Těšín (Czech Republic, Region of Silesian Moravia, municipality of Český Těšín) (

Figure 1). Before 1920, the towns of Cieszyn and Czech Cieszyn (Český Těšín) separated by the river Olse/Olza were one and the same town, Teschen, situated in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. After the First World War, Teschen was divided and the western bank became Czechoslovakian (under the name of Český Těšín), the eastern portion becoming Polish (Cieszyn). During the Second World War, the two towns were temporarily reunited before being separated once again in 1945. Today, the two towns constitute an important point of communication as they form the main road passage between the north and south of Europe [

73]. The population of Cieszyn is 35,000 and Czech Cieszyn (Český Těšín) is 25,000 [

73,

74]. Until 1989, there had been no form of cooperation between Cieszyn and Těšín. Crossing the border was not easy, despite Poland and Czechoslovakia both belonging to the Soviet bloc. It was only in 1998 that the two towns and the neighboring municipalities decided to sign an agreement to pave the way for institutionalized cooperation within the Euroregion Cieszyn Silesia. Nowadays, the Euroregion is the main actor in terms of CBC and has helped with the implementation of several projects in several areas, including culture, education, the environment, spatial planning, transport, natural hazard management and prevention. The cross-border conurbation of Cieszyn-Česky Těšin functions like a capital for the Euroregion [

75]. The cooperation of the Euroregion was based on the “Cieszyn Silesia development strategy”; however, both cities have not yet prepared a bilateral strategy for cross-border cooperation.

The cross-border thematic alliance “Ciesz się Cieszynem—ogród dwóch brzegów” (“Enjoy Cieszyn—the Two Shores Garden”, in 2004, co-financed by INTERREG program) was the first joint action of both cities. It concerned spatial development as well as social and economic revival of the Polish and Czech border banks of the river Olza while respecting the environmental values of the area. Its aim was also to reduce tourism and passenger traffic and the intensity of these areas use by the inhabitants to maintain their biodiversity. The aim of this alliance was to create a space friendly to residents and tourists on both sides of the river Olza, using the landscape and historical values of both cities in a sustainable way, breaking the existing perception of this space as an area excluded from use.

The analysis of the case study on the cross-border thematic alliance “Ciesz się Cieszynem—ogród dwóch brzegów” was carried out within the framework presented in

Table 1 below.

The main reasons for starting cooperation and developing a strategy for the development of the Olza river banks in Cieszyn and Czech Cieszyn include:

- (i)

the common problems of both cities connected with the development of the Olza river banks, which in the communist era were of strategic importance and were controlled by the army. After the borders were opened, the stereotypes and habits still functioning within the society hindered the development of this area;

- (ii)

after the collapse of communism, the tourist attractiveness of Cieszyn and Czech Cieszyn increased, which was a living testimony to socio-economic changes in Central Europe. The gradual unification of both cities has mobilized local governments to act with a view to increase the attractiveness of both cities for residents and tourists.

- (iii)

the unique environmental values and biodiversity of the Olza river bed required the provision of spatial solutions limiting uncontrolled exploitation by residents and the pressure of tourist traffic;

- (iv)

the possibility of using both cities to co-finance joint investments under the INTERREG program, integrating investment activities in both parts of the borderland and stimulating the development of cross-border cooperation.

The funds obtained from the INTERREG IIIA Czech Republic-Poland 2004–2006 program and the involvement of both cities’ own budget funds have been instrumental for the concept of spatial development of both banks of the Olza river. “Enjoy Cieszyn—the Two Shores Garden” and the implementation of a plan for the development of the cross-border alliance of Cieszyn and Czech Cieszyn, formed part of several projects related to further stages of this investment.

Spatial development of communal areas belongs to the communes’ statutory tasks both in Poland and in the Czech Republic. Management and governance structure of both cities within the framework of the cross-border alliance took place at the level of subsequently implemented cross-border projects, in which one of the cities was always the leader. These were projects co-financed from the European Regional Development Fund through the INTERREG program. In each project, four key principles of cross-border cooperation were considered:

- (i)

joint preparation of the project (each partner participates in the preparation of the project);

- (ii)

joint implementation of the project (each partner provides the necessary resources; activities are carried out on both sides of the border and they addressed to stakeholders from both countries);

- (iii)

common staff (a joint project team is made up of competent representatives of each partner);

- (iv)

joint financing (each partner participates financially in the costs of the joint project).

All cross-border projects implemented with the support of the INTERREG program also considered EU horizontal principles: sustainable development, equal opportunities, and non-discrimination, as well as gender equality.

Due to the rigid conditions for the implementation of cross-border projects co-financed from the INTERREG program, other entities, e.g., entrepreneurs or non-governmental organizations, could not be directly involved in the development of the alliance. All activities were carried out directly by the self-governments of both cities. Greater involvement of other stakeholders was observed only in the next stages of the alliance development, in the context of using the results of individual projects and linking them with the goals of these organizations and institutions.

The dynamic evolution of the alliance manifested itself in the activities carried out simultaneously in both cities, as part of subsequent cross-border projects included in the urban study and development strategy of the border area located along the Olza river in Cieszyn and Czech Cieszyn. The projects were implemented in accordance with these strategic documents and the conditions for cross-border cooperation, resulting from the guidelines of the INTERREG program. They were also consistent with the individual strategies of both cities [

76,

77]. The development of the cross-border alliance of Cieszyn and Czech Cieszyn with regard to the spatial development of the Olza river banks is presented in

Table 2 below.

Co-financing of projects from the INTERREG program funds since the establishment of the cross-border alliance was decisive for its character and objectives. The alliance was developed based on successive, implemented cross-border projects aimed at achieving common goals. On the one hand, it limited the flexibility of activities, but at the same time guaranteed diligence of implementation and striving to achieve the designated results, which was a condition for reimbursement of funds. However, the use of public support did not allow any commercial activities to be carried out, nor did it allow direct involvement of entrepreneurs, as it would result in public aid participation. For this reason, the projects focused only on public and non-profit activities, which did not allow full use of the potential of this cross-border cooperation. At the same time, the development of the alliance with the use of INTERREG program funds guaranteed its simultaneous impact on both border cities, which is the supreme attribute of cross-border projects.

Based on the project documentation, it should be added that the results of all projects were measured in line with the indicators provided for in the INTERREG program for this type of project, and they were achieved. These indicators, included in the documentation of the projects, are concerned mainly by the assessment regarding:

- (i)

the number of partners involved in joint operations;

- (ii)

the relationship between the results of investment activities and the costs of their implementation;

- (iii)

the relationship between the results of non-investment activities and the costs of their implementation;

- (iv)

the number of entities that will be engaged in cross-border cooperation during the project sustainability period;

- (v)

the number of promotional and information activities aimed at developing cross-border cooperation within projects.

The performance of the alliance depends on internal and external conditions relating to the implementation of projects co-financed from the INTERREG program. Internal conditions can be defined as dependent on entities involved in the alliance, e.g., Cieszyn and Czech Cieszyn city self-governments, and their organizational units. These include:

- (i)

accuracy and comprehensiveness of the developed strategy for the development of the Olza waterfront in Cieszyn and Czech Cieszyn;

- (ii)

quality of applications for co-financing of individual cross-border projects implementing the alliance’s development plan;

- (iii)

qualifications and competences as well as motivation of the project team consisting of representatives of both partners;

- (iv)

ability to cooperate, and quality of communication between representatives of both cities;

- (v)

ability to ensure and maintain the cross-border effect of individual projects.

On the other hand, external conditions concerned objective factors on which the entities developing the alliance had no influence. They were related, among others to:

- (i)

mode of obtaining and using subsidies from the INTERREG program;

- (ii)

legal conditions for the implementation of infrastructure investments in Poland and the Czech Republic

- (iii)

environmental values and biodiversity of areas where projects were implemented

- (iv)

needs and expectations of target groups, i.e., inhabitants of both cities and cross-border tourists

- (v)

involvement of other stakeholders at the level of both cities in the utilization of the results of cross-border projects

- (vi)

involvement of other stakeholders at the level of both cities in the utilization of the results of cross-border projects, e.g., other public institutions, entrepreneurs, non-governmental organizations.

The performance consequences for organizations entering alliances were varied. All previous stages of the development of the alliance have been achieved because of the funds obtained for this purpose. These projects yielded tangible results: in both cities a significant modernization of the urban space was carried out, there was visible development of cross-border tourism and the resident interest in spending free time on the Olza river waterfront increased, and the natural values and biodiversity occurring in the area were preserved. These effects are in line with the goal of forming an alliance. As far as using the experience from this alliance to improve the capacity of both cities to further develop cross-border cooperation is concerned, the conclusions are not so unequivocal. It was found that co-financing from the INTERREG program, which significantly facilitated the creation and development of the alliance, also became its significant limitation. This is due to the following circumstances:

- (i)

the need to implement cross-border projects in a rigid partnership resulting from the conditions for applying for EU funds in practice, which limited the interest and involvement of other entities and institutions in cooperation, which did not allow the synergy and scale to be used in cross-border cooperation;

- (ii)

although the development of the alliance was based on a multi-stage spatial development strategy for of the Olza river banks, the cooperation horizon was set by individual projects, which hindered constant, harmonious cooperation and setting long-term cooperation goals;

- (iii)

the cross-border alliance contributed to the development of cooperation between Cieszyn and Czech Cieszyn only in a narrow (yet very important for both cities) sphere of joint development of the border area; however, it did not directly affect the expansion of cooperation in other spheres;

- (iv)

the results of the development of the cross-border alliance were not visible immediately after the completion of individual projects, but only after a certain time, and overlapped in the long term; hence it is difficult to say which stage of the alliance proved to be the most effective and which was the least effective;

- (v)

in accordance with the requirements for the use of subsidies from the INTERREG program, both cities have the obligation to maintain the effects of implemented projects for at least 5 years after the completion of each of them, which indicates some coercion and not the spontaneity of further cooperation under the pain of the EU financing repayment.

Bearing in mind the above conclusions, it was hypothesized that to ensure sustainable cross-border cooperation between Cieszyn and Czech Cieszyn, it is important to:

- (i)

develop cross-border cooperation between Cieszyn and Czech Cieszyn by creating further cross-border alliances in areas important for both cities, using the existing experience;

- (ii)

development of cross-border alliances with direct involvement of stakeholders from different environments who are really interested in it, especially entrepreneurs and non-governmental organizations;

- (iii)

creating new alliances in a more flexible formula, with the limitation of co-financing from EU funds;

- (iv)

development and implementation of a long-term cross-border cooperation strategy at the level of both cities, including all relevant stakeholders and thematic areas.

5. Figures and Results

The structure of the research respondents and their answers for the research questions are presented in

Table 3 below.

The varied participation in the research of individual categories of respondents results from the specificity of their involvement in the alliance on both sides of the border, as well as from the slightly different social structure of both cities. On the Polish side, the involvement in the alliance of local governments and public institutions, as well as non-governmental organizations that implement a significant part of public activities, is dominant. In turn, on the Czech side, in addition to local governments and public institutions, enterprises took greater part in the research (almost comparable to non-governmental organizations), which are interested in developing cross-border cooperation between both cities, among other things due to its economic interest. A relatively small research sample was not an obstacle to achieving the research objective, as it was a targeted sample of respondents involved in the creation and development of the examined cross-border alliance. The answers obtained for subsequent research questions are presented below in

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6.

The greatest involvement in the development of the alliance is demonstrated by local self-governments, which are also best prepared for its development (

Table 4) and cooperate the longest in the alliance (

Table 6). These results coincide with the case study, where it was shown that the initiators of the cooperation were local self-governments, which from the very beginning were managing the alliance independently through subsequent cross-border projects. Public institutions are well-prepared for cross-border cooperation, but it is not permanent. Non-governmental organizations are slightly better prepared for cross-border cooperation than companies, although they focus mainly on periodic and ad hoc cooperation. In some cases, cooperation lasts over 5 years, and in others it is just beginning. A similar approach to the alliance is presented by companies, of which only a small number develop permanent cross-border cooperation over a longer period (

Table 4 and

Table 5). The results of the research, interpreted in the aspect of the previous case study analysis, prove that:

- (i)

the purpose of a cross-border alliance is associated mainly with public (local government) tasks, hence the involvement in the development of this cooperation of non-governmental organizations and companies is much smaller;

- (ii)

the formula of the cross-border alliance (projects co-financed from EU funds, implemented only by public beneficiaries) is not conducive to direct involvement of other stakeholders, as it is not formally possible in this type of project; thus, NGOs or companies are not able to fully participate in the development of the alliance and do not develop enough competence for cross-border cooperation;

- (iii)

basing the cross-border alliance solely on the long-term implementation of a single planning document implemented by self-governments and public institutions did not encourage non-governmental organizations and companies to engage more in cooperation, as the benefits that could be derived from it were not clearly outlined;

- (iv)

local self-governments responsible for the alliance developed it exclusively based on projects co-financed from EU funds, without additional complementary activities involving other stakeholders in cross-border network cooperation between the two cities.

The research results confirm the hypothesis that the development of sustainable cross-border alliances requires direct or even formal involvement of various stakeholder groups (not only local governments and public institutions). At the same time, each group of stakeholders, especially non-governmental organizations and enterprises, should be well prepared to develop cooperation on various levels and acquire at least one permanent partner and understand the opportunities and benefits that cooperation can bring them.

The evaluation of the previous impact of the studied alliance on possible areas of social and economic cooperation was made by comparing the opinions of respondents from Cieszyn and Czech Cieszyn (

Table 7). The assessment of the alliance on both sides of the border is similar. Its impact hitherto on both cities can be considered sustainable primarily in areas such as transport, nature and landscape protection, sport, recreation and tourism, spatial planning and development planning, and administrative cooperation. Most of them are the domain of public administration. In addition, the respondents expect that in the future the impact of the alliance will also extend to the sphere of cooperation within culture and the removal of barriers in mutual relations. Respondents, however, do not see the clear impact of the alliance on the development of economic cooperation. The alliance is mainly located in the public sphere, responsible for social activities, with reference to the environmental sphere (nature and landscape protection); the economic sphere is clearly neglected. Respondents also assess that the impact of the cross-border alliance on the sphere of nature and landscape protection as well as spatial planning and development planning will slowly disappear (low assessments of these areas in the perspective of the future impact of the alliance). This is a signal that the respondents believe that some possibilities of cooperation in the cross-border alliance under investigation will be exhausted, but at the same time it should open to new areas. They include security or social integration and economic cooperation. At the same time, the respondents indicate that further cross-border alliances should be concluded, inter alia, in the sphere of transport, security and economic cooperation.

The results of the research confirm the hypothesis that based on current experience of cooperation within the alliance, both further development of current directions of cooperation (the same areas of cooperation under the alliance indicated as current and future, while the respondents on both sides of the border agree that some areas of cooperation will disappear), as well as the development of alliances in new areas, not resulting from the current cooperation, is possible.

Respondents and stakeholders of the cross-border alliance of Cieszyn and Czech Cieszyn expect both cooperation transformation within the alliance (gradual vanishing of cooperation in some areas and replacement with new ones), as well as creating further alliances in other areas. As the creators of these processes, the local self-governments of both cities are indicated, as well as the Euroregion Cieszyn Silesia. These are entities from the public sphere and this is probably the alliance model closest to the respondents. It is worth noting that with the involvement of the Euroregion Cieszyn Silesia, the alliance could gain a more networked dimension, with the participation of stakeholders from outside Cieszyn and Czech Cieszyn. Polish respondents also attribute a large role in creating cross-border alliances to the inhabitants, which results from the increasingly popular participatory approach to local development on the Polish side. On the other hand, on the Czech side, non-governmental organizations and entrepreneurs are attributed a greater role. Particularly large discrepancies occur in assessing the involvement of enterprises in the development of cross-border cooperation on both sides of the border (

Table 8). This may indicate a different approach to the future shape of cross-border alliances: on the Polish side there is the expectation that they will have a self-government and social dimension, while on the Czech side the alliances are seen as a balanced cooperation of several groups of stakeholders: local government officials, representatives of non-governmental organizations and entrepreneurs with strong support from the Euroregion Cieszyn Silesia. Undoubtedly, the most important actors of cross-border cooperation remain local governments, which should be responsible for creating a strategy for cross-border cooperation between the two cities, including alliances, involving different groups of stakeholders, depending on their expectations and opportunities to participate in cross-border cooperation. Very high and high demand for the development of such a strategy is reported by as many as 93.4% of Polish respondents and 80% of Czech respondents (

Table 9). It should be assumed that cooperation is possible only in those areas where interest has been declared on both sides of the border. Therefore, the research confirmed the hypothesis that ensuring permanent cross-border cooperation between the two cities requires drawing up and implementing a long-term cross-border cooperation strategy at the level of both cities, including all relevant stakeholders and thematic areas. It is particularly important to emphasize that each future cross-border alliance will be based on the individual involvement of various stakeholder groups who will be directly responsible for its development and the expected results of cooperation.

In the opinion of respondents, cross-border alliances should be financed primarily from public funds, both national and international (

Table 10). This determines the preferred model of cooperation in which public entities dominate, as well as non-governmental organizations that can also use such funds. Only half of Polish respondents and nearly one third of Czech respondents’ point to the financing of cooperation from enterprise funds, which would shift the area of this cooperation towards an economic one. For this to happen, it is necessary to create a much higher demand for cooperation in the economic sphere, which is currently of secondary importance.

Therefore, the hypothesis that the creation of new cross-border alliances will take place in a more flexible formula with limited use of EU funds has not been confirmed. Respondents of the survey, as the dominant stakeholders, are public entities using public financing sources. It should be noted, however, that the possibilities of financing further development of cross-border cooperation from European funds are conditioned by their future availability, which is not guaranteed. In the future, three scenarios for the development of cross-border alliances of Cieszyn and Czech Cieszyn are possible:

- (i)

combining cooperation in current areas and extending cooperation to new areas with the dominant involvement of public and non-governmental entities, mainly based on European funds and national public funds;

- (ii)

deepening cooperation in current areas and new areas, with the dominant involvement of public and non-governmental entities (European funds and national public funds) and parallel development of new, more commercialized areas of cooperation, e.g., in the field of transport or tourism;

- (iii)

maintaining cooperation at the current level or even limiting it in current areas on the part of public and non-governmental entities (among others due to low availability of European and national funds for this purpose) and parallel development of new, more commercialized areas of cooperation, e.g., in the field of transport or other areas of economic cooperation.

In the aspect of planning alliances between Cieszyn and Czech Cieszyn, scenario II, which ensures the balance between the public and commercial spheres, while respecting the environment, should be considered optimal. For this scenario, the next chapter presents the key stages of creating a cross-border cooperation strategy based on alliances involving various entities, developed in various spheres.

6. The Main Stages of the Strategy Building Process for the Cross-Border Alliance of Border Cities

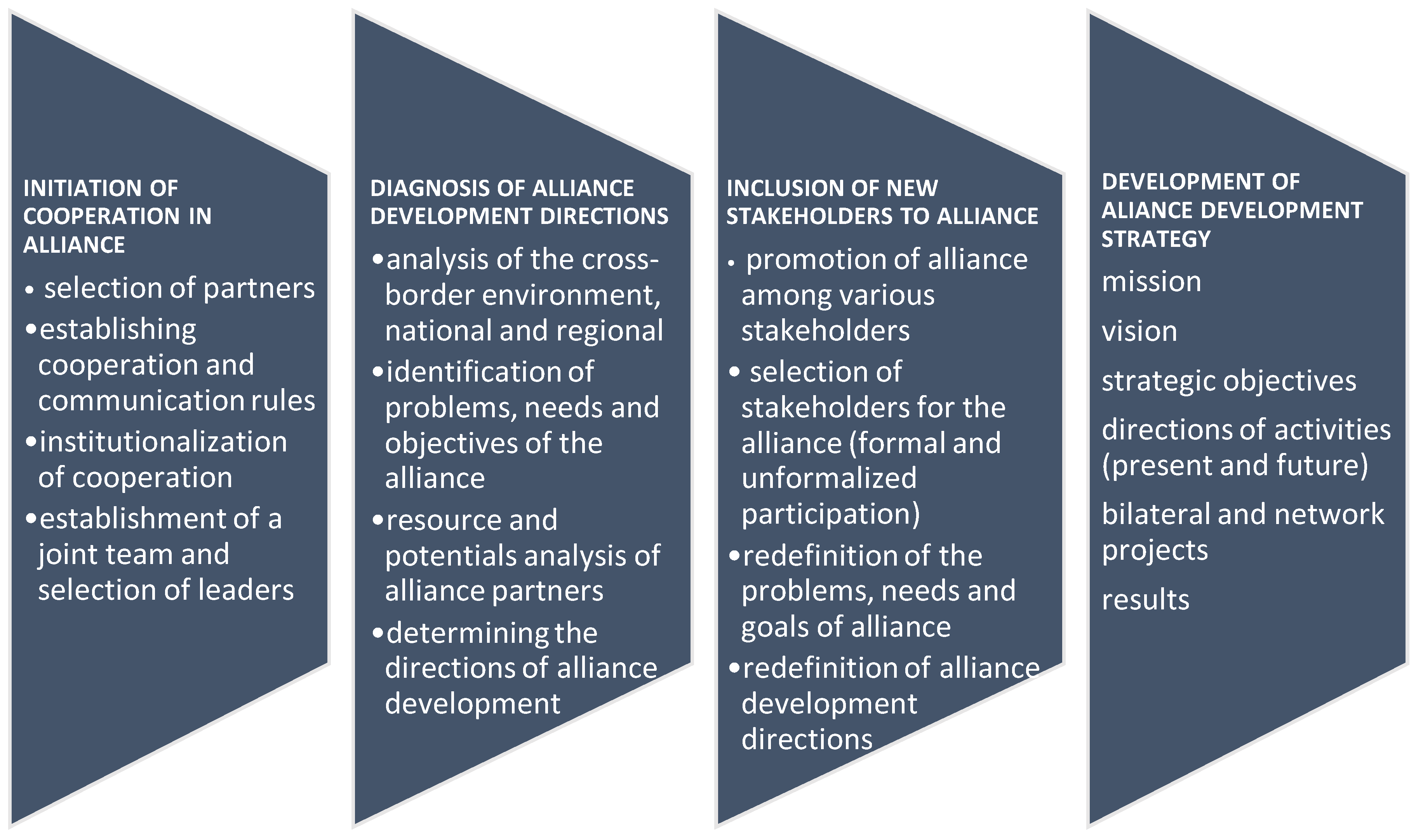

Based on the assumptions regarding sustainable development planning for border areas, as well as the analyzed case study and surveys that verify the research hypotheses set out in the paper, the key stages of the strategy-building process for alliances of cross-border border cities are discussed. The presented concept is oriented towards the development of network cooperation between various stakeholder groups. The key stages of this process are shown in

Figure 2.

The creation of an alliance should be based on the cooperation of entities with the potential and resources for sustainable development of cross-border cooperation. Institutionalizing cooperation (e.g., conclusion of an agreement, consortium agreement, etc.) is an important factor stabilizing the alliance and ensuring its continuity and durability. As results from the research, the best leaders of cross-border alliances are local governments as they have institutional competences for broader assessment of the needs for cross-border cooperation, also from the point of view of other stakeholders. Therefore, the development of cross-border alliances of border towns should be based on the involvement of local self-governments as leaders.

In addition to formal institutional cooperation in the alliance, direct cooperation in the project team is equally important. The project should involve competent professionals, including leaders prepared to manage cross-border cooperation, both bilateral and network, and able to communicate in an international team.

Only understanding and good cooperation between the alliance partners, as well as the leaders and representatives of the partners in the project team, can ensure the effective development of the alliance.

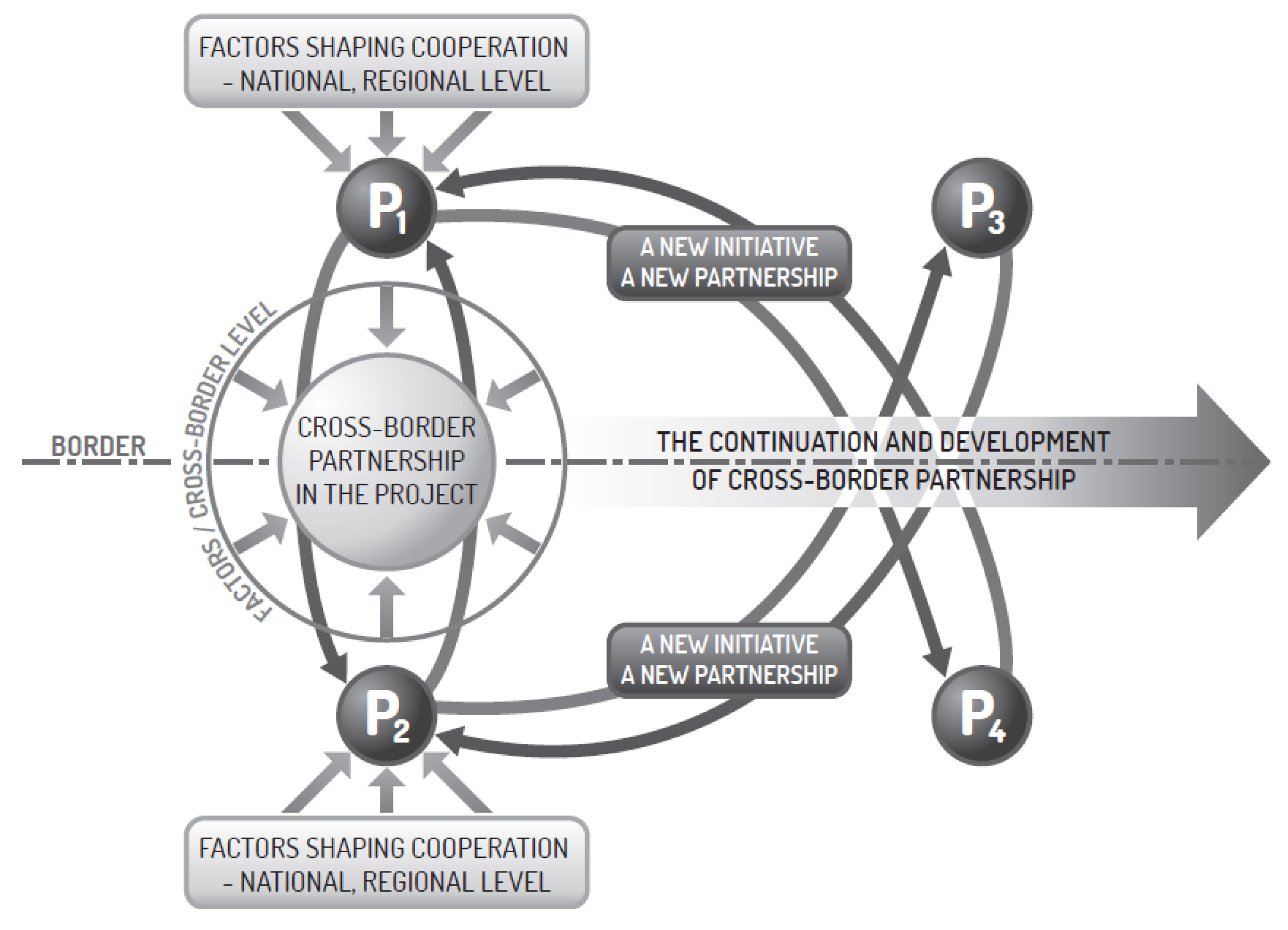

The diagnosis of the directions of the alliance development should be based on the analysis of the partners’ environment, including the common cross-border environment as well as the national and regional environment of each cooperating city (P1, P2, according to

Figure 3), considering factors important for both the initiators of the alliance and other stakeholders that can join the alliance (e.g., P3 and P4, according to

Figure 3).

Factors resulting from the national and regional environment of partners include:

- (i)

availability of national structures of cross-border cooperation (e.g., Euroregions),

- (ii)

national and regional legal, economic, and social conditions, promoting or hindering the development of cross-border cooperation,

- (iii)

attractiveness of cross-border cooperation from the point of view of other paths to achieve similar goals at the national level,

- (iv)

popularization of standards and good practices for the development of cross-border cooperation

The factors influencing the alliance at the cross-border level can be divided into [

78]:

- -

factors related to partnership in alliance (the level of trust between partners; quality and dynamics of relationships between partners; common value system between partners; agreement on the objectives and scope of cooperation; tolerance for: cultural, linguistic, ideological, etc. differences)

- -

factors related to the cross-border region where the alliance develops (system support provided for the development of CBC at the EU level and on the border; similarity of historical and socio-economic background of the neighboring border regions; geopolitical situation in the countries developing cross-border cooperation; demand for the integration from local borderland communities; common policy of borderline development; availability of EU funds for development of the borderlands; efficiency of other competing partnerships).

The continuation and development of the partnership (alliance), which shaped this cross-border cooperation under the influence of various factors, was also considered. The development of the cross-border alliance is also determined by the correct matching of the resources and potentials of the partners to identify common problems, needs and goals, considering the principle of sustainable development.

This approach to the process of building a cross-border cooperation strategy is unique since as a starting point for the development of cooperation, a cross-border alliance of two local governments is adopted. These two local governments intend to co-operate with other partners, transforming the bilateral relationship into a network. As a rule, strategies for developing cross-border cooperation are defined at the level of regions or Euroregions, where the network cooperation processes develop in a natural way. However, it is much more difficult to develop network cooperation at the city level. There is a lack of appropriate instruments for this (including local funds for cooperation), and in order for such cooperation to develop, it is necessary to mobilize other stakeholders from both cities much more strongly. Therefore, in further considerations, these mechanisms are discussed in detail.

Figure 3 presents a mechanism for transforming a project partnership, e.g., a cross-border alliance of border cities, into new partnerships built by other stakeholders. The continuation and development of the partnership (alliance), which shaped this cross-border cooperation was also taken into consideration under the influence of various factors. The development of the cross-border alliance is also determined by the correct matching of resources and potential of the partners to identify common problems, needs and goals, considering the principle of sustainable development.

To ensure sustainable cross-border partnership leading to sustainable borderland development, the activities should be implemented in a sustainable way, on both sides of the border by at least two partners from the neighboring countries. The key objective of the development of cross-border partnerships is not only the integration of neighboring communities on the border areas, but also harmonious and sustainable development of these areas and strengthening their competitiveness in relation to more developed areas of the Union. Sustainable development of cross-border partnerships is therefore a desirable mechanism reflecting the expectations of local communities regarding opportunities for cross-organizational cooperation within borderlands. A partnership should pursue individual goals of the cooperating organizations with implications for their environment.

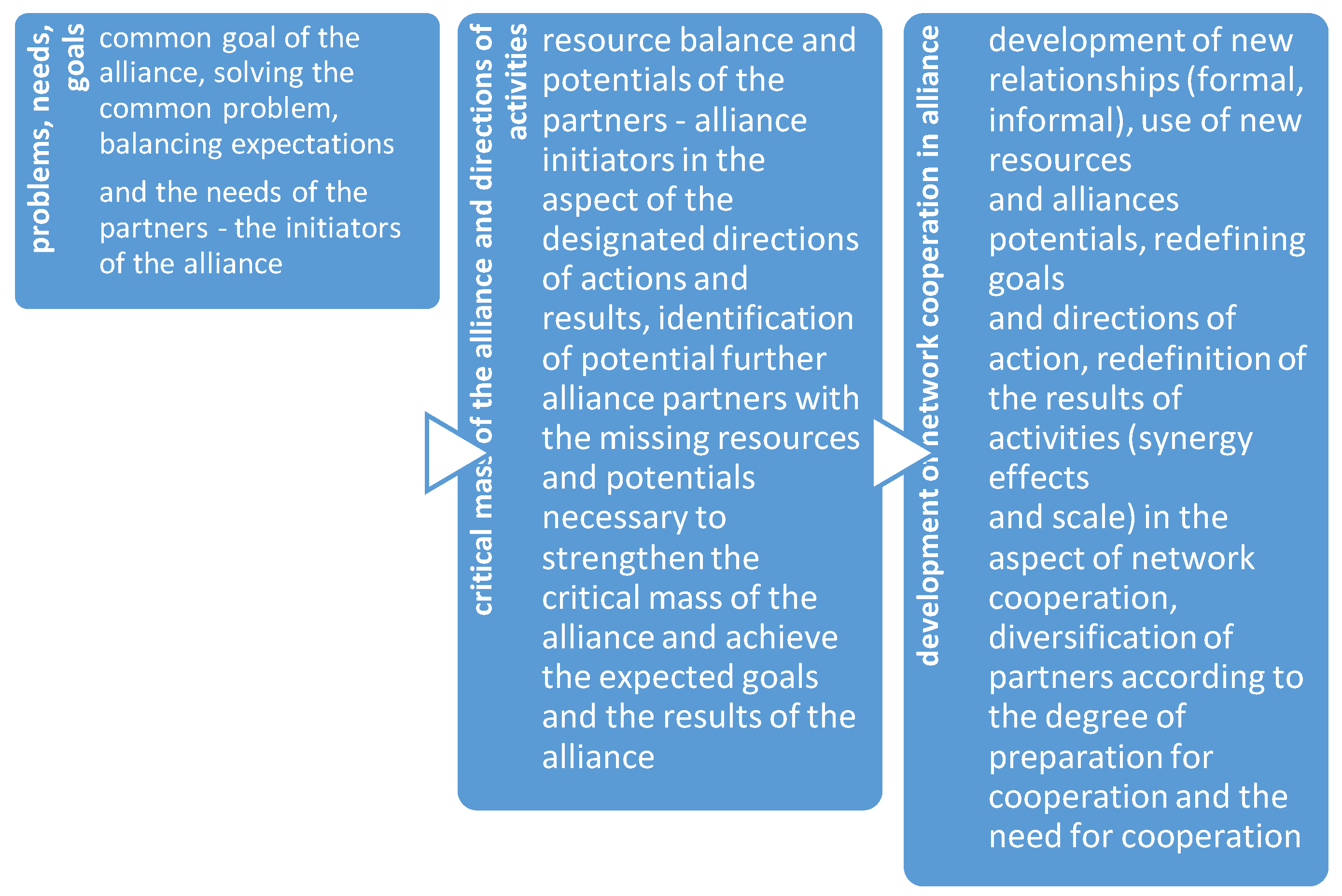

The key activities related to the transformation of the cross-border bilateral alliance into a cross-border network alliance are shown in

Figure 4.

The success of the alliance depends both on the selection of partners, but also on the directions of the alliance policy. It should be in line with the objectives of network cooperation, and not only the cooperation of the alliance leaders, because this approach would in principle make it impossible to obtain other entities to cooperate, as demonstrated by the case study discussed previously for the cities of Cieszyn and Czech Cieszyn. To ensure the sustainability of the cross-border alliance, the following conditions for the development of network cooperation can be adopted:

- (i)

Defining goals and directions of activities that consider social, economic, and environmental aspects in the cross-border dimension. In the discussed case study for Cieszyn and Czech Cieszyn, the focus was on social and environmental aspects, taking into account the economic aspect (weak involvement of entrepreneurs in the alliance), which resulted in the inability to use the economic potential of this alliance)

- (ii)

Ensuring participation in alliance of various groups of stakeholders, bringing various resources and potentials, which positively affects the synergy and scale effect in network cooperation,

- (iii)

Involvement of both partners with extensive experience in cross-border cooperation, as well as those who do not have such experience, who report high, average, or low cooperation needs,

- (iv)

Ensuring the coherence of the key objective of cross-border cooperation for all participants in the alliance on both sides of the border,

- (v)

Ensuring that the results of the alliance bring comparable benefits on both sides of the border.

The above considerations indicate that the development of a document containing the strategy for the development of the cross-border alliance should take place only when the participants of the alliance are joined by subsequent participants interested in the development of cross-border cooperation within this alliance. Defining the mission, vision and strategic goals of the alliance is the responsibility of the initiators who, in accordance with the model presented in

Figure 4, are most responsible for its development.

It is extremely important to capture all the relationships that will be established as part of the network cooperation that develops in the alliance [

79]. Each additional partnership is realized in the implementation of subsequent projects and achieving additional results, which constitute the added value of network cooperation in the cross-border alliance. It is difficult to assume that all participants of the cross-border alliance will cooperate with each other with equal intensity and sustainability. Certainly, there will be numerous asymmetries related to e.g., the organizational structures of partners, their financial potential, impact on other network participants, interest in selected areas of cooperation, etc. Some of the new relationships established in the framework of the cross-border alliance will evolve into separate and independent partnerships over time and then in subsequent alliances. This is also confirmed by the results of research carried out in Cieszyn and Czech Cieszyn.

The research also shows that there is a high demand among the participants of the cross-border alliance to develop a cooperation strategy that would also define its future areas. A well-prepared strategy for the development of a cross-border alliance in the network cooperation model should, therefore, consider the future directions of actions related to three main aspects:

- (i)

the needs and goals of alliance leaders responsible for its continuation and development,

- (ii)

the needs and objectives of the other participants of the alliance, strengthening its critical mass enabling survival and further development of cross-border cooperation in current and new directions,

- (iii)

the needs and objectives of borderland development, being in line with the national and regional environment of the partners, as well as the cross-border environment, in the social, economic, and environmental dimension.

It is also important to mention that another key condition for the development of cross-border alliance is high awareness and good preparation of each group of stakeholders, especially non-governmental organizations and enterprises to enlarge the cooperation at various levels. First, cooperating partners should understand the opportunities and benefits that cooperation can bring. It is important to motivate them to develop the cross-border networks.

7. Final Remarks

It is increasingly acknowledged that the identification of critical factors for CBC success represents, together with the definition of new strategies based on those factors, a crucial step towards development of border regions of European countries, since CBC projects can contribute not only to tackling aforementioned problems but also to enabling the creation of resilient and sustainable cities, and strengthening potential synergies of territorial development. These issues gain increasing emphasis when we know that in several countries more than half the population lives across the border, tending to be more affected by common policy-making, and by the gaps that plague such policies.

The present study enabled us to conclude that the use of the case study research method constitutes a feasible approach to identify specific conditions promoting the success of CBC projects:

- (i)

correctly defining the alliance goals;

- (ii)

ensuring the participation in alliance of various groups of stakeholders;

- (iii)

involving both partners with extensive experience in CBC;

- (iv)

ensuring the coherence of the key objective;

- (v)

guaranteeing the alliance benefits both sides.

Moreover, the methodology used enabled not only the identification of key challenges and difficulties felt by European countries on the implementation of specific CBC projects, identified and reviewed throughout the research, but also the verification that regardless of all the efforts made in recent years in order to strengthen CBC in several countries around the world [

80,

81,

82,

83,

84] there is still a long way to go in order to achieve a sustainable methodology based on objective principles that might contribute to support the creation of multiple benefits across economic, environmental, sociocultural and political aspects in CBC projects. Still, the performed analysis put forward specific problems among CBC projects mostly related to the duplication of equipment in nearby areas, lack of basic services and infrastructures within the CBC influence area, and limited data sharing relating to common planning options between cities, which emphasizes the aforementioned problems, among other issues of concern on CBC processes that should be reviewed and rethought, given the negative trend they might introduce on these processes. These aspects acquire increasing importance especially in cities in which it is evident that the duplication of equipment and infrastructures contributed directly to the lack of capacity to perform and or acquire essential services and public infrastructures by both cities. This reality brings to light an apparent misuse of public money that has a clear impact on the quality of life of the people living in these cities. This fact corroborates the findings put forward by Castanho et al. [

3] according to which regardless of all the CBC political considerations and the advertisements received by CBC projects, investment continues to be developed according to individual political goals, following discrete political, economic, environmental, and social agendas.

Likewise, even if as mentioned before, the preformed research enables the identification of specific conditions promoting the success of CBC projects, CBC alliances depend both on the selection of partners, but also on the envisioned politic directions, which should be in line with the objectives established for the network, and not only based on the leaders’ ideas, since this approach would generally make it impossible to obtain other entities to cooperate [

85,

86], as demonstrated by the case study discussed previously for the cities of Cieszyn and Czech Cieszyn.

In summary, the performed research enabled us to put forward noteworthy conclusions on the relevance of the establishment of alliances on CBC development projects, and on the main aspects that should be considered throughout the planning process of a CBC project. In fact, though no one single size fits all, there are some critical issues that, if considered, might contribute definitely to the success of any cross-border cooperation strategy. Building trust, involving all relevant partners, and fomenting a perceptive sense of belonging might not be a miraculous recipe, but they are generally relevant aspects towards CBC success.

8. Limitation of the Studies and Future Directions

The paper is based on qualitative research, including CATI and CAWI, which were conducted on a deliberately chosen sample, not a representative one. This sample was sufficient to study the alliance of the small cities of Cieszyn and Czech Cieszyn. More accurate results would be based on statistical analysis that would build an economic model for this problem, which could be done using MANCOVA analysis followed by univariate ANOVAs with some dependent variables in rounds. The authors intend to use these methods in subsequent studies.

Further areas of research that the authors intend to pursue will primarily concern the assessment of attitudes and actions of particular groups of actors developing cross-border cooperation in the border cities of Cieszyn and Czech Cieszyn. Individual types of behavior aimed at the transformation of bilateral cross-border cooperation in the network cooperation within the alliance will also be assessed as presented in detail as

Figure 3. The authors also want to verify to what extent the network relationships that developed as part of the alliance met the requirements for sustainable cross-border cooperation as defined in the last part of

Section 6.