An Exploratory Study of Swedish Charities to Develop a Model for the Reuse-Based Clothing Value Chain

Abstract

1. Introduction

Research Question: What Are the Main Factors Affecting a Reused-Based Clothing Value Chain?

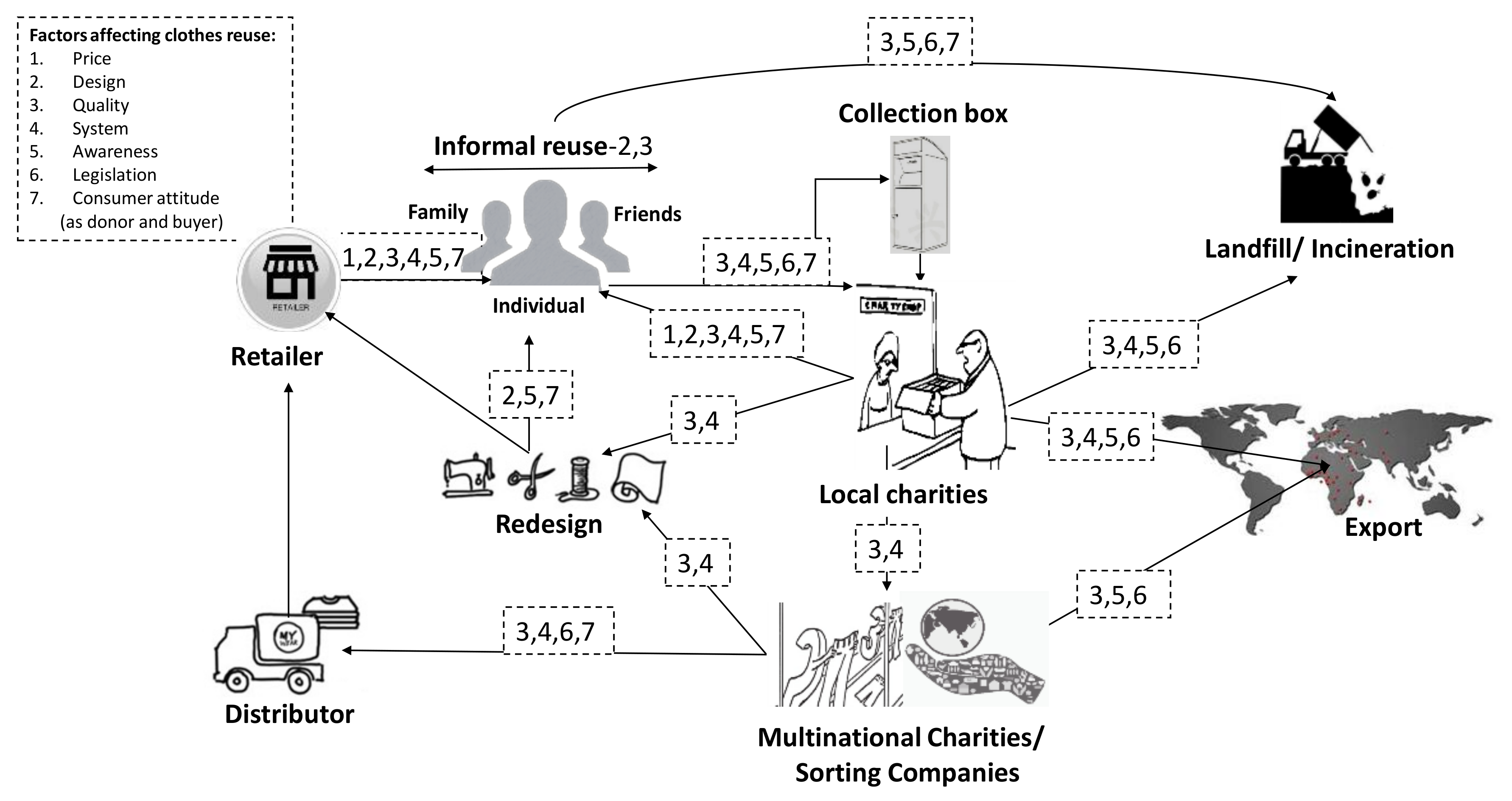

2. Reuse-Based Clothing Value Chain

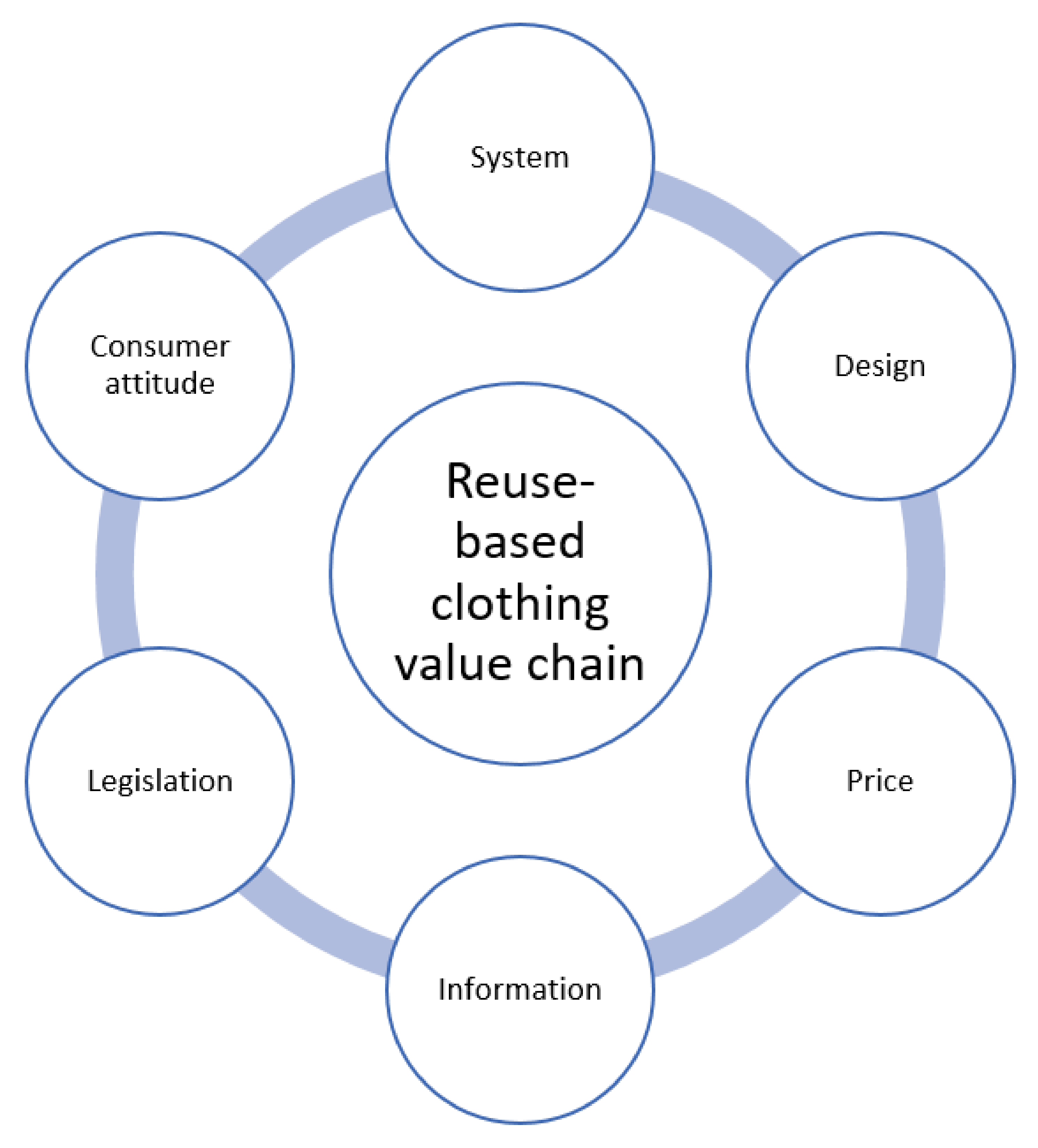

3. Factors Affecting the Reused-Based Clothing Value Chain

3.1. System

3.2. Design

3.3. Price

3.4. Information

3.5. Legislation

3.6. Consumer Attitude as a Donor and Buyer

4. Methodology

4.1. Case Design

4.2. Data Collection and Analysis

5. Findings

5.1. Current Practice in the Selected Organizations

5.2. Cross-Case Synthesis

5.2.1. System

“The second-hand business is a money generator for us. Hence, it is very much important to have good working conditions for employees/volunteers, and offer the best shopping experience to the customers. The new premises will have a proper storage facility and provide a dust-free working environment”

5.2.2. Design

“Design of second-hand clothes certainly matters, as customers are visiting stores from different cities in search of vintage”.

“Design, brand, and price for any product matter together. Customers first look for good brand/design, then have a look on price. Beside this, often ladies are coming in search of long black dresses which are rarely available in our shop”.

“Yes, these days, many companies are selling goods to Africa. Hence, good quality and design clothes are in high demand. Especially, summer clothes are in demand in Africa because of the hot weather”.

5.2.3. Price

“Customers are attentive to product prices, and we have competition with other second-hand stores in the region”.

“Design, quality, and price of the product matter simultaneously for the customers. The purchase decision is made on the basis of all factors”.

5.2.4. Information

“How long have you been here? I have never heard about your store”

5.2.5. Legislation

“Government decision to withdraw the value added tax for second-hand charity organizations is a great relief for us”.

5.2.6. Consumer Attitude as a Donor and Buyer

The behaviour of the customers varies, almost 80% of people come with good quality clothes, while the remaining come with poor quality clothes. Sometimes, even garbage is found in the bins, maybe this is due to a mistake”.

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jayaraman, V.; Luo, Y. Creating competitive advantages through new value creation: A reverse logistics perspective. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2007, 21, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernon, M.; Rossi, S.; Cullen, J. Retail reverse logistics: A call and grounding framework for research. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2011, 41, 484–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.E.; Mollenkopf, D.A.; Stolze, H.J. Natural resource scarcity and the closed-loop supply chain: A resource-advantage view. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2013, 43, 351–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dururu, J.; Anderson, C.; Bates, M.; Montasser, W.; Tudor, T. Enhancing engagement with community sector organisations working in sustainable waste management: A case study. Waste Manag. Res. 2015, 33, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Torres, A.J.; Ablanedo-Rosas, J.H.; Mukhopadhyay, S. Supplier allocation model for textile recycling operations. Int. J. Logist. Syst. Manag. 2013, 15, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitala, K.; Klepp, I.G. Consumers’ Clothing Reuse: P otential in Informal Exchange. J. Consum. Policy 2014, 38, 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawley, J.M. Digging for Diamonds: A Conceptual Framework for Understanding Reclaimed Textile Products. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2006, 24, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Jeong, B. Profit Analysis and Supply Chain Planning Model for Closed-Loop Supply Chain in Fashion Industry. Sustainability 2014, 6, 9027–9056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, D.S.; Tibben-Lembke, R. An examination of reverse logistics practices. J. Bus. Logist. 2001, 22, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cojocariu, C.R. The Reverse Gear of Logistics. Rev. Manag. Comp. Int. 2013, 14, 153–164. [Google Scholar]

- Fleischmann, M.; Bloemhof-Ruwaard, J.M.; Beullens, P.; Dekker, R. Reverse logistics network design. In Reverse Logistics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 65–94. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, M.; Daly, L.; Towers, N. Lean or agile: A solution for supply chain management in the textiles and clothing industry? Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2004, 24, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, G. Aspects of sustainable supply chain management (SSCM): Conceptual framework and empirical example. Supply Chain Manag. 2007, 12, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibben-Lembke, R.S.; Rogers, D.S. Differences between forward and reverse logistics in a retail environment. Supply Chain Manag. 2002, 7, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, N. The apparel aftermarket in India—A case study focusing on reverse logistics. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2011, 15, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dervojeda, K.; Verzijl, D.; Rouwmaat, E. EU-circular-supply-chains. Bus. Innov. Obs. EU. 2014. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/DocsRoom/documents/13396/attachments/3/translations (accessed on 8 March 2017).

- Morley, N.J.; Bartlett, C.; McGill, I. Maximising Reuse and Recycling of UK Clothing and Textiles A Research Report Completed for the Department for Environment, Food and October 2009; Oakdene Hollins: Aylesbury, UK, 2009; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Palm, D.; Elander, M.; Watson, D.; Kiørboe, N.; Salmenperä, H.; Dahlbo, H.; Moliis, K.; Lyng, K.-A.; Valente, C.; Gíslason, S. Towards a Nordic Textile Strategy: Collection, Sorting, Reuse and Recycling of Textiles; Nordic Council of Ministers: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gregson, N.; Beale, V. Wardrobe matter: The sorting, displacement and circulation of women’s clothing. Geoforum 2004, 35, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palm, D.; Elander, M.; Watson, D.; Kiørboe, N.; Salmenperä, H.; Dahlbo, H.; Rubach, S.; Hanssen, O.-J.; Gíslason, S.; Ingulfsvann, A.-S. A Nordic Textile Strategy: Part II: A Proposal for Increased Collection, Sorting, Reuse and Recycling of Textiles; Nordic Council of Ministers: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hvass, K.K. Weaving a Path from Waste to Value: Exploring Fashion Industry Business Models and the Circular Economy. Ph.D. Thesis, Copenhagen Business School, Frederiksberg, Denmark, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Farrant, L.; Olsen, S.I.; Wangel, A. Environmental benefits from reusing clothes. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2010, 15, 726–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.-H.; Li, Q.; Chen, X.-J.; Wang, Y.-F. Sustainable Rent-Based Closed-Loop Supply Chain for Fashion Products. Sustainability 2014, 6, 7063–7088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolridge, A.C.; Ward, G.D.; Phillips, P.S.; Collins, M.; Gandy, S. Life cycle assessment for reuse/recycling of donated waste textiles compared to use of virgin material: An UK energy saving perspective. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2006, 46, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paras, M.K.; Pal, R.; Ekwall, D. Systematic literature review to develop a conceptual framework for a reuse-based clothing value chain. Int. Rev. Retail Distrib. Consum. Res. 2017, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allerston, P. Reconstructing the second-hand clothes trade in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Venice. Costume 1999, 33, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isla, V.L. Investigating second-hand fashion trade and consumption in the Philippines: Expanding existing discourses. J. Consum. Cult. 2013, 13, 221–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, L. Trade and transformations of secondhand clothing: Introduction. Textile 2012, 10, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, S. Charity shops in the UK. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 1998, 26, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tipper, M.J.; Drivas, I.; Russell, S.J.; Ward, G.D.; Morley, N. Principles of the recovery and reuse of corporate clothing. Proc. ICE Waste Resour. Manag. 2010, 163, 165–172. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, E. Charity retail: Past, present and future. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2002, 30, 586–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B. Fashion Supply Chain: Lessons from H&M. Sustainability 2014, 6, 6236–6249. [Google Scholar]

- Botticello, J. Between classification, objectification, and perception: Processing secondhand clothing for recycling and reuse. Textile 2012, 10, 164–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkazam. Textile Science & Engineering Automated Sorting Technology from T4T Can Help Improve Recovery and Efficiency. J. Text. Sci. Eng. 2013, 3, 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Cervellon, M.C.; Carey, L.; Harms, T. Something old, something used: Determinants of women’s purchase of vintage fashion vs second-hand fashion. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2012, 40, 956–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLong, M.; Heinemann, B.; Reiley, K. Hooked on vintage! Fash. Theory J. Dress Body Cult. 2005, 9, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, C.; Birtwistle, G. Sell, give away, or donate: An exploratory study of fashion clothing disposal behaviour in two countries. Int. Rev. Retail Distrib. Consum. Res. 2010, 20, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekstrom, K.M.; Salomonson, N. Reuse and Recycling of Clothing and Textiles—A Network Approach. J. Macromark. 2014, 34, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, R. Sustainable Business Development through Designing Approaches for Fashion Value Chains. In Roadmap to Sustainable Textiles and Clothing: Environmental and Social Aspects of Textiles and Clothing Supply Chain; Springer Science + Business Media: Singapore, 2014; pp. 227–261. [Google Scholar]

- Morana, R.; Seuring, S. End-of-life returns of long-lived products from end customer- insights from an ideally set up closed-loop supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2007, 45, 4423–4437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, N.P. Innovations for home dressmaking and the popularization of stylish dress. J. Am. Cult. 1994, 17, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, E.C. Nearly new: The second-hand clothing trade in eighteenth-century Edinburgh. Costume 1997, 31, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemire, B. The secondhand clothing trade in Europe and beyond: Stages of development and enterprise in a changing material world, C. 1600–1850. Textile 2012, 10, 144–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiot, D.; Roux, D. A second-hand shoppers’ motivation scale: Antecedents, consequences, and implications for retailers. J. Retail. 2010, 86, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyasaki, F.; Wakolbinger, T.; Kettinger, W.J. The value of information systems for product recovery management. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2013, 51, 1214–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, P.A.; Autry, C.W.; Wilcox, W.E. Liquidity implications of reverse logistics for retailers: A Markov chain approach. J. Retail. 2005, 81, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorasayan, J.; Ryan, S.M. Optimal price and quantity of refurbished products. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2006, 15, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Rivera, R.; Ertel, J. Reverse logistics network design for the collection of End-of-Life Vehicles in Mexico. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2009, 196, 930–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liu, W.; Wei, J. Pricing and Remanufacturing Decisions of a Decentralized Fuzzy Supply Chain. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2013, 2013, 986704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atasu, A.; Guide, V.D.R., Jr.; Van Wassenhove, L.N. Product reuse economics in closed-loop supply chain research. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2008, 17, 483–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Dutta, P. Design and analysis of a closed-loop supply chain in presence of promotional offer. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2015, 53, 141–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketzenberg, M. The value of information in a capacitated closed loop supply chain. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2009, 198, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abimbola, O. The international trade in secondhand clothing: Managing information asymmetry between west African and British traders. Textile 2012, 10, 184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, L.R.; Birtwistle, G. An investigation of young fashion consumers’ disposal habits. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2009, 33, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Shi, L.; Feng, X.; Li, K. Reverse channel design: The impacts of differential pricing and extended producer responsibility. Int. J. Shipp. Transp. Logist. 2012, 4, 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.-M.; Zhao, Z.; Ke, H. Dual-channel closed-loop supply chain with government consumption-subsidy. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2013, 226, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-E.; Lee, K.-D. Integrated forward and reverse logistics model: A case study in distilling and sale company in Korea. Int. J. Innov. Comput. Inf. Control 2012, 8, 4483–4495. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, W.M.; Ting, D.H.; Wong, W.Y.; Khoo, P.T. Apparel acquisition: Why more is less? Manag. Mark. 2012, 7, 437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, C.; Birtwistle, G. Consumer clothing disposal behaviour: A comparative study. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiller Connell, K.Y. Exploring consumers’ perceptions of eco-conscious apparel acquisition behaviors. Soc. Responsib. J. 2011, 7, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goworek, H. Social and environmental sustainability in the clothing industry: A case study of a fair trade retailer. Soc. Responsib. J. 2011, 7, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wiegerinck, V.; Krikke, H.; Zhang, H. Understanding the purchase intention towards remanufactured product in closed-loop supply chains An empirical study in China. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2013, 43, 866–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norum, P.S. Examination of Apparel Maintenance Skills and Practices: Implications for Sustainable Clothing Consumption. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2013, 42, 124–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paras, M.K.; Curteza, A. Revisiting upcycling phenomena: A concept in clothing industry. Res. J. Text. Appar. 2018, 22, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernadi, P. Literary interpretation and the rhetoric of the human sciences. In The Rhetoric of the Human Sciences; The University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Routledge: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Czarniawska, B. Narrating the Organization: Dramas of Institutional Identity; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Herriott, R.E.; Firestone, W.A. Multisite Qualitative Policy Research: Optimizing Description and Generalizability. Educ. Res. 1983, 12, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellram, L.M. The use of the case study method in logistics research. J. Bus. Logist. 1996, 17, 127–132. [Google Scholar]

- Czarniawska, B. Social Science Research: From Field to Desk; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, S. InterViews: An Introduction to Qualitative Research Writing; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Research; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, D. Interpreting Qualitative Data; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann, S. Qualitative Inquiry in Everyday Life: Working with Everyday Life Materials; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Collier, J.; Collier, M. Visual Anthropology: Photography as a Research Method; UNM Press: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, D.H.; Wieder, D.L. The Diary: Diary-Interview Method. J. Contemp. Ethnogr. 1977, 5, 479–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Propp, V. Morphology of the Folktale, 2nd ed.; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Greimas, A.J.; Courtés, J.; Crist, L.; Patte, D. Semiotics and Language: An Analytical Dictionary; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Paras, M.K.; Pal, R. Application of Markov chain for LCA: A study on the clothes ‘reuse’ in Nordic countries. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 94, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, L. Tracking Globalization: Recycling Indian Clothing: Global Contexts of Reuse and Value; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lehr, C.B.; Thun, J.-H.; Milling, P.M. From waste to value—A system dynamics model for strategic decision-making in closed-loop supply chains. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2013, 51, 4105–4116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Organization | Number of Visits | Observations | Interviews (Face to Face) | Documents | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Duration | ||||

| A | 07 | Participatory observation as a volunteer in the textile leftover section. | Indivi4dual | Founder (>1 h) and chief operation manager (>1 h) | Grading category list, advertisement pamphlet, feedback forms, and accounting sheets |

| Observed process of sorting and reprocessing. | |||||

| Multiple visits to various sections of the organization. | |||||

| B | 01 | Visit to shop, collection (unloading), sorting and reprocessing sections. | Individual | Founder (>1 h) | Accounting sheets. |

| C | 03 | Visit to shop, sorting and reprocessing sections. | Individual | Founder (>1 h) | Video files, organisation brochure, accounting Sheets |

| D | 03 | Visit to shop, sorting and reprocessing sections. | Individual | Founder (>1 h) | None |

| E | 02 | Visit to shop, collection (unloading), sorting and reprocessing sections. | Group | Four managers (>1 h) | Sales sheets |

| Details | Organization A | Organization B | Organization C | Organization D | Organization E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collection methods | 1. On-call service for bulk donation. 2. Direct handover | 1. On-call service for bulk donation. 2. Direct handover 3. Collection Bins | 1. Direct handover | 1. Direct handover2. On-call service | 1. Collection Bins 2. Direct handover |

| Type of donation | 1. Personnel and household2. Industrial leftover fabrics and trims | 1. Personnel and household 2. Industrial leftover fabrics and trims | 1. Personnel and household | 1. Personnel and household 2. Unsold items form retail & online stores | 1. Personnel and household |

| Availability of transportation | Inbound | Inbound/Outbound | No | Personnel car used | Sister organization |

| Sorting facilities | Manual Sorting | ||||

| Sorting criteria | Perfect- Sweden in different categories, Winter-Romania,Winter (good quality)—Finland. All Others- Africa (In different Categories), Defected-Garbage. | Good Quality- Sweden, All Other- Latvia in different Categories | Good Quality- Sweden/ self-store, Rest Other- Central Warehouse, Defected- Recycling Station. | Normal Quality- Sales in store, Good quality- Sorted for collector store, Summer Clothes- Africa, Others- Eastern Europe, Dirty/Washable- for cleaning, Specific Order- for ChurchDefected- Recycling | |

| Reprocessing facilities | Ironing, Minor by hand. | Ironing, Minor by hand, Cleaning facilities for rare use. | Ironing, Minor by hand, Cleaning facilities for rarer use. | Ironing, Minor by hand. | Ironing, Minor by Machines. Full cleaning facilities/order for cleanings are also taken. |

| Sale | A limited amount of in-house sale Majority sale to Africa | A limited amount of in-house sale Majority donation to Latvia. | Almost 40% are sold in house the remaining is sent to a central warehouse. | Almost 40% are sold in house the remaining is sent to a central warehouse. | A limited amount of In-house sale The majority are taken back by the collection company. Collector pays 1 SEK for every 2 kg of sorted clothes. |

| Organization | Approach to Bring Awareness |

|---|---|

| A | Word-of-mouth Publicity, Newspaper Advertisements, Internet, Posters and Signboards |

| B | News Coverage and Promotion by Latvia government |

| C | Advertisements, Inviting people groups, Social media and International charity organization websites |

| D | Advertisements, International charity organization websites and Planning to start a social media webpage and own website |

| E | Advertisements. |

| Organization | Government Legislation Benefits |

|---|---|

| A | Incentives for disabled, prisoner, and alcoholic person employment. Contribution by job agencies for unskilled/training person. |

| B | European Union support for starting up. Municipality incentives for disabled persons. Contribution by job agencies for unskilled/training person. National social agencies support for social work. |

| C | Financial help from an International Charity organisation. |

| D | Disabled and training/unskilled persons worked in the past. |

| E | Salary to the employees. Daily allowance to all disabled persons. All expenses, including rent, by local government. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Paras, M.K.; Ekwall, D.; Pal, R.; Curteza, A.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L. An Exploratory Study of Swedish Charities to Develop a Model for the Reuse-Based Clothing Value Chain. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1176. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10041176

Paras MK, Ekwall D, Pal R, Curteza A, Chen Y, Wang L. An Exploratory Study of Swedish Charities to Develop a Model for the Reuse-Based Clothing Value Chain. Sustainability. 2018; 10(4):1176. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10041176

Chicago/Turabian StyleParas, Manoj Kumar, Daniel Ekwall, Rudrajeet Pal, Antonela Curteza, Yan Chen, and Lichuan Wang. 2018. "An Exploratory Study of Swedish Charities to Develop a Model for the Reuse-Based Clothing Value Chain" Sustainability 10, no. 4: 1176. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10041176

APA StyleParas, M. K., Ekwall, D., Pal, R., Curteza, A., Chen, Y., & Wang, L. (2018). An Exploratory Study of Swedish Charities to Develop a Model for the Reuse-Based Clothing Value Chain. Sustainability, 10(4), 1176. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10041176