1. Introduction

Food security is a complex mix of production and supply constraints as well as access to nutritious food. With a distinctly spatial character, food security solutions often take ungeneralizable forms. Scaling up development interventions within the agricultural sector specifically targeting food security challenges is frequently proposed as a solution to the global hunger crisis (e.g., [

1]). While the phrase ‘scaling up’ is extensively used across Research and Development (R&D) institutions and in Natural Resource Management (NRM) literature, experience has shown that the term lacks ontological agreement [

2,

3,

4]. Further, scaling up is often used broadly to refer to a variety of processes [

3], or occurs concurrently with discussions on innovation, particularly agricultural innovation, and concepts related to spatial diffusion when there are in fact important distinctions.

Approaches and viewpoints on scaling exist across a range of disciplines [

5]. Further, interpretations of scaling are often driven by perspective and perceptual bias [

6]. One view of scaling is results-based, increasing impact to reach a greater number of people (e.g., [

1]). How impact is achieved involves additional perspectives on scaling up including the expansion of programs, technologies, or projects from pilot experiences to larger enterprises. To deliver multiplier impacts, scaling up investment too, is critical. An added dimension relates to policy and governance: what is appropriate at one level may not be suitable at another [

5,

7]. Spatially-based perspectives often involve the expansion of a technology or intervention’s geographic reach (e.g., [

8]), or estimating impact at larger scales from small-, field-, or plot-sized experiments (e.g., [

9]). Wigboldus et al. [

10] present a considerable literature review on scaling perspectives exercised through a wide range of approaches, notably: agricultural systems, interdisciplinary, transdisciplinary, research, innovation systems, value chain, landscape, socio-ecological systems, transitions to sustainability, and the multi-level perspective on socio-technical transitions. Other relevant perspectives are those held directly by the observers or actors involved in the scaling up process: developers, donors, extension agents, and farmers. In this analysis, we approach scaling up from a development perspective giving particular consideration to scaling up interventions targeting food security challenges. We accept that while scaling up is not always a positive force, or the only pathway for development [

11], effective scaling up of development interventions is often cited as a measure of success in reducing food insecurity.

Working towards food security solutions involves a wide range of actors embedded within myriad social and environmental systems. Given this inherent complexity, the number of actors, and often necessity for collaboration between development partners to achieve sustainable impacts, a clear, ontological understanding of what scaling up means is essential. Herein, ontological disagreement refers to the varied meanings of scaling up inherent within institutional definitions. Imprecision of definitions across institutions and actors creates ambiguity in defining and measuring outcomes of scaling programs. In turn, uncertainty of scaling up from the onset of development programs contributes not only to inflated reports of success, but failure of programs to actually scale as either a product or process.

The purpose of this article is not to call for improved definitions, but given scales’ widespread application, we argue for precision of definitions where scale is considered both as a function of outcome (noun) and process (verb). To explore the varied meanings of scaling up across institutions, a text analysis is presented of adopted definitions across institutions, pointing to a conflation of scaling up operating as an Intervention, Mechanism, or Outcome. The article concludes with the introduction of a conceptual framework that gives greater consideration to separating scales’ functions, as an outcome or process, along with the necessary role of monitoring and evaluation on both innovation and development scaling up efforts.

3. A Visual Analysis of Scaling Up

To explore the varying interpretations of scaling up in development literature, definitions (when available) from the 15 CGIAR Centers, United States Agency for International Development (USAID, Washington, DC, USA), and IFAD, were illustrated in a TagCrowd™ word cloud in order to visually analyze the text. Definitions included in this analysis from the CG Consortium were from the following institutions: International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA, Beirut, Lebanon), International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT, Cali, Colombia), International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT, Patancheru, India), International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI, Washington, DC, USA), International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI, Nairobi, Kenya and Addis Ababa, Ethiopia), International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT, El Batán, Mexico), and World Agroforestry Center (ICRAF).

Analysis began by creating a text file containing all available definitions across institutions of ‘scaling up.’ Where multiple definitions were presented from one institution, all definitions were included in analysis. For study purposes the terms, ‘scaling’, ‘projects,’ ‘successful’, and ‘agriculture’ were removed from each definition. The file was uploaded to TagCrowd™ where a maximum number of words to display was set to twenty-five; minimum frequency was set to 1. The result is presented in

Figure 1 where for each word in the word cloud, its size is proportional to the frequency it is found in institutions’ definitions.

The word cloud contained twenty-four terms. One term, ‘sustainable’, dominates the rest as the most frequently applied term, followed by nine terms of relative importance given their similar size: ‘people’, ‘process’, ‘technologies’, ‘impact’, ‘environment’, ‘adapting’, ‘expanding’, ‘policies’, and ’programs.’ Given the similar frequency of the remaining words, we elected to use only the top ten terms in the remainder of our analysis.

Across the institutions considered in this study, analysis of the ten words most commonly used in the definitions of scaling up reveal a distinct categorization of terms emphasizing individually or a combination of, Interventions, Mechanisms, or Outcomes. We arrived at this categorization by considering the terms through the lens of the formalized components to scaling: innovation, scaling, and monitoring an evaluation; or more directly, what is being scaled, how is scaling occurring, and ultimately to what end? Interventions refers to the ‘whats’ of scaling: what is being scaled up to meet the end goal of developing sustainable food security solutions? Interventions often take the form of new or adapted, existing innovations. Here, definitions across institutions point to technologies, policies, or programs; interventions which are suspected to have long-standing, positive impacts. The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) definition highlights these specifically: “Scaling up means expanding, replicating, adapting, and sustaining successful policies, programs, or projects to reach a greater number of people” [

1]. The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) echoes this sentiment in their emphasis on scaling referring to access and effective use of agricultural technologies by poor farmers: “[Scaling up] means that more poor farmers benefit from access to an effective use of agricultural technology” [

28]. It is worth noting the profound difference between an explicit measure of numbers and broadly defined access. Finally, IFAD, in choosing to define scaling up adopts similar verbiage to IFPRI where scaling again means, “Expanding, replicating, adapting and sustaining successful policies, programs, or projects in geographic space and time to reach a greater number of rural poor” [

29].

Mechanisms refers to the “how tos” of scaling up: how is scaling up being conducted? Adapting and expanding both function as mechanisms of scaling up. Likewise, the term ‘process’ alludes to the mechanics of working on and accomplishing a scaling up program. Uvin [

4] introduced the concept of scaling as a process, which, despite Menter et al.’s [

3] dissention, is a term still frequently applied in the literature. The International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) gives particular attention to process: “Scaling is the act of increasing the size, amount, or importance of something, usually an organization or process” [

30]. Expanding on the idea of scaling up as a process, most recently Wigboldus and Brouwers [

23] moved beyond the processes described by Uvin to further include scaling up as quantitative, spatial, kinematic, or physical. The advantage of calling scaling up a process is that it is binary—a yes or no proposition. From a development perspective, you can declare success by meeting an indicator of process rather than outcome. It sets a low bar. An added dimension is management. Writing for the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) Menter et al. [

3] (p. 9) state, “Scaling up is a management issue. It us about how to manage projects to ensure that positive impact is maximized.”

Beyond the Interventions and Mechanisms are the Outcomes of scaling up: what is the end result? Here we come to the most often applied term in the description of scaling up, sustainable. Closely related is impact. Both terms not only apply to end results but to intentions. The World Agroforestry Center (ICRAF) places particular emphasis on outcomes: “[Scaling up means] to bring more benefits to more people, more quickly and more lastingly” [

31]. For many, at the center of scaling up development interventions is the idea of reducing food security challenges for smallholder farmers; impactful programs are successful at working towards or meeting this end goal. Likewise, sustainable programs are those that work at maintaining success in reducing the burden of hunger over time. A related point to consider is resiliency; the ability to recover after disaster or unforeseen circumstances. The mission of the CG Consortium emphasizes improvement in resiliency directly, however, when considering the visual analysis of scaling definitions presented, it is worth noting that the term ‘resilient’ is absent altogether. Yet, both an emphasis on sustainability and resiliency are necessary to meeting long term food security challenges. These two terms are not interchangeable, nor should the idea of resiliency be absorbed by sustainability entirely; the approaches to sustainable versus resilient programs and their scaling can have distinct differences.

Many of the definitions included in this analysis emphasize not one, but a combination of Interventions, Mechanisms, or Outcomes in their definition of scaling up, leading to ambiguity in their meaning. Returning to USAID’s definition, emphasis is placed both on Mechanisms through agricultural technologies and Outcomes: that more poor farmers have access to and effectively utilize aforementioned technologies. The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) combines all three where through scaling up strategies, “development practitioners expect to implement successful interventions and expand, adapt, and sustain them in different ways over time for greater developmental impact” [

32]. The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI)‘s definition provides an excellent example too. Scaling up is, “Expanding, replicating, adapting, and sustaining successful policies, programs, or projects to reach a greater number of people [

1] (p. 46).” Given this definition, is scaling up about policies, programs, or projects, their expansion, replication, or adaptation, or their sustainability in reaching a wider audience?

4. Discussion

The phrases, ‘scaling up’ and ‘going to scale’ are used extensively throughout the R&D and NRM literature. Yet, as several studies have highlighted, they lack ontological agreement. Uvin [

4] (p. 928) argues that the, “variety of definitions is important. It allows us to look at the phenomenon in a number of different ways, giving us some insight into the complexity of the associative sector itself.” We disagree, as ultimately the answer to the question, “what is scaling?” impacts both how scaling up is operationalized (i.e., the intervention and/or the pathways to scaling), influences M&E, and affects program success. Likewise, how scaling up is defined will influence how funding is allocated, and in turn how project development progresses—which projects are made a priority and which are neglected. Given the varying definitions and interpretations of scaling up, Wigboldus and Leeuwis [

33] (p. 6) caution that, “we always need to verify how different people interpret the overall concept of scaling (up) and related concepts” in order to promote shared learning and efforts across actors. The generic nature of scaling up the authors contend does little to aid in knowing what scaling measures may best apply in a particular situation.

As we have highlighted in this paper, how scaling up is defined is rooted in the interpretation of scale itself. When considering the categorization of terms presented in our earlier analysis (Interventions, Mechanisms, Outcomes), it becomes apparent that scale is applied in two forms: as a verb and a noun. Where scale functions as a verb is demonstrated directly in the mechanics of scaling up with emphasis on adaptation and expansion of innovations. Innovations are a critical component to achieving widespread impacts in reducing food insecurity, either through new innovation or scaling up existing, successful innovations [

13]. As a noun, an innovation taken to scale implies meeting a specified end goal; project outcomes. Likewise, in the evaluation of project results in relation to its predefined, intended outcomes that were determined at the onset. Existing definitions of scaling up often conflate ideas related to interventions (innovations), the process of their expansion or replication, or their intended outcome; we contend this occurs in part due to the application of scale both as a noun and verb. To illustrate the application of scale as either (or both) a

noun and

verb, we return to IFPRI, USAID, ILRI, and ICRAF’s definitions of scaling up:

“Expanding, replicating, adapting, and sustaining successful policies, programs, or projects to reach a greater number of people.”

“More poor farmers benefit from access to an effective use of agricultural technology”

“Scaling is the act of increasing the size, amount, or importance of something, usually an organization or process.”

“Bring more benefits to more people, more quickly and more lastingly.”

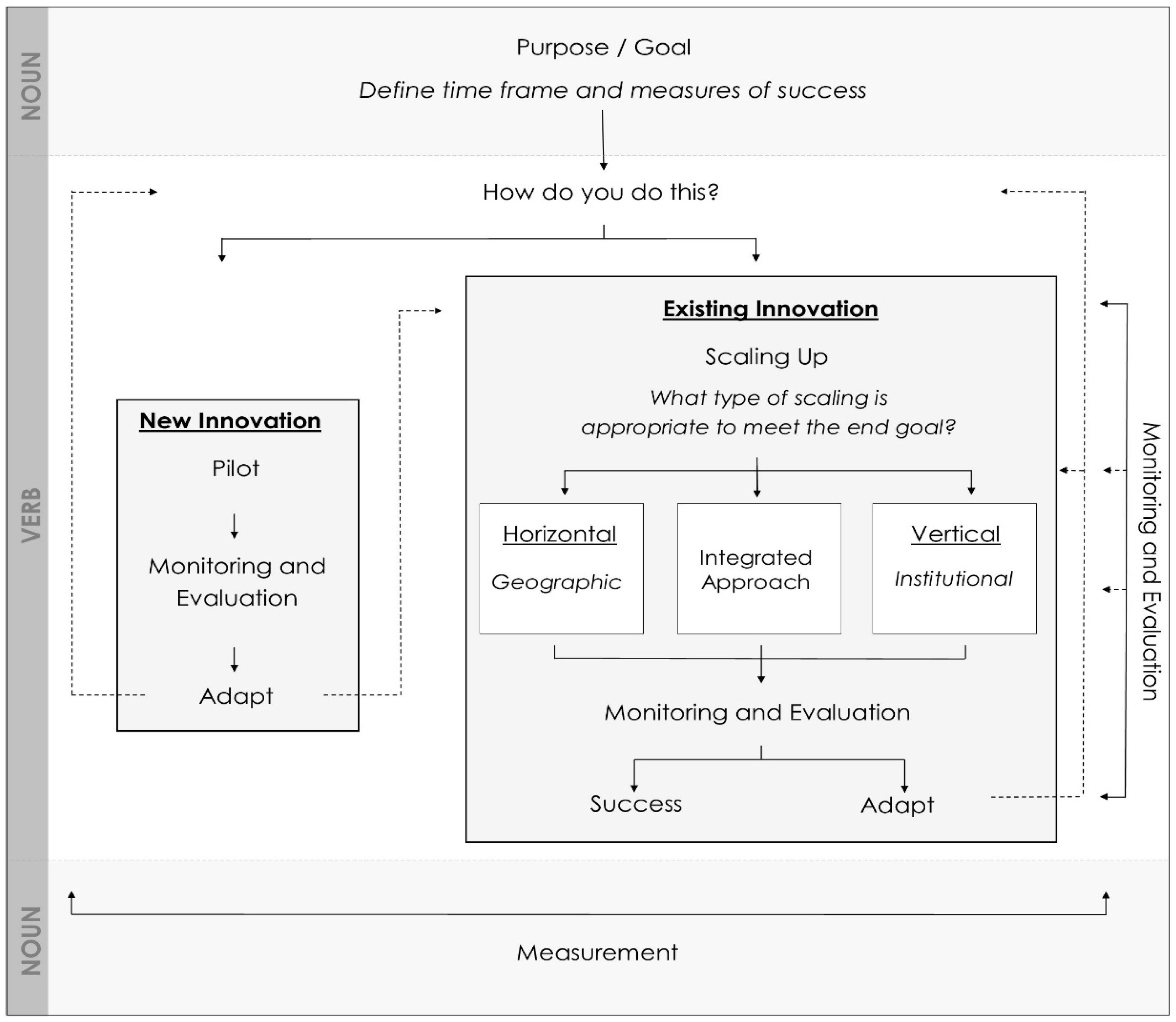

To separate scaling up and its associated actions based on the process (verb) and outcomes (noun), we present a conceptual framework for defining scaling up and putting it into practice for development activities (

Figure 2). Further, we emphasize the necessary role of Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E) on both the innovation and scaling up efforts.

During the initial stage, scale functions as a noun: a specific purpose or program goal is agreed upon, followed by defining its measures of success and the overall timeframe for the project or program completion. Measures of success are quantifiable outcomes of the innovation or scaling that serve to evaluate program performance. How to achieve these outcomes varies by either developing a new innovation or scaling an existing innovation. Here too, the question of whether scaling an existing innovation is even appropriate to the context should be addressed [

2]. It is at this stage that scale begins to function as a verb. After development, new innovations follow a pathway through piloting, monitoring and evaluation, then, adaptation. It should be noted that it is often this necessity for adaptation, coupled with imprecise definitions of scaling up that work to declare every program a success.

Scaling up existing innovations starts with careful consideration of which type of scaling is appropriate to meet the end goal. Vertical scaling up is institutional; innovations are meant to guide principles of practice. Horizontal scaling up is geographic, where the spatial reach of an innovation expands. Scaling up efforts do not occur in isolation; Vertical scaling up efforts spillover to geographic diffusion across space, likewise geographic expansion can influence uptake of institutional practice. Often scaling up requires an integrated approach [

2]. Giving consideration to an integral pathway aims at scaling up along both an institutional and geographic pathway from the onset. An integrated approach can be either sequential or simultaneous depending on the context.

Regular M&E of scaling up pathways provides important feedback and creates opportunities for adaptation from onset to completion. Rather than evaluating what went right or wrong at the conclusion of a project, effective M&E strategies attempt to gauge performance through a series of indicators throughout a project’s lifespan [

34]. Monitoring and Evaluation is a requirement for effective scaling up [

35]. Yet historically, scaling up efforts and evaluation were often viewed as conflicting objectives for most international development agencies [

36], despite the value of reliable program evaluations at every stage of scaling up efforts. In this model, the M&E process occurs both for new and existing innovations; likewise, on the scaling up efforts to bring an innovation to scale. M&E specific to scaling up efforts is conducted during several stages: (1) The choice of existing innovation to be brought to scale; (2) The type of scaling up pathway selected-vertical, horizontal, or integrated; (3) On horizontal, vertical, or integral scaling up efforts; and (4) On the declaration of success or choice to adapt.

The final stage returns to scale, the noun. It is at this point that measurement between the stated indicators for success and actual outcomes are evaluated. Here, overall program performance is analyzed, and through careful consideration of program shortcomings, new initiatives developed to meet remaining unmet needs of communities.

5. Conclusions

It is trite to call for improved definitions, particularly given the outcomes of this paper; here, we argue for the careful consideration of the precision of definitions used. The imprecision of definitions, in part the product of uncertainty, contributes not only to the reported regular success of development programs, but also the failure of these programs to scale as both product and process. Literature is replete with examples of attempts to address the scaling up debate, many of which are highlighted herein. Often these discussions include an attempt to redefine or reinvent the terminology to better describe the meaning of scaling up to fit a particular development program rather than stressing the precision of terms already in use. Yet, regular redefinition only leads to the perpetuation of uncertainty particularly where adoption of these improved definitions are asynchronous across institutions. Given the importance of scaling up to development, ontological agreement of scaling up across institutions is vital not only to measurement but to meeting the needs addressed through sustainable development interventions. Ontological ambiguity devalues scaling up; by defining a clear pathway for success, value judgements regarding development as outcome can be examined.

Our analysis on the interpretations of scaling up showed that across the different agencies considered, definitions were dissimilar despite some commonalities in etiology and occasionally authorship. The issue here is not alternative phrasing, but rather the lack of ontological agreement among definitions. The categorization of terms highlighted when analyzing the descriptions of scaling up are a byproduct of the varied meanings behind the definitions themselves. In some cases, emphasis is placed primarily on the innovation being scaled (Interventions). Other interpretations give priority to the structure of the scaling up process itself including institutional or geographical expansion (Mechanisms). Still others underscore the end results (Outcomes) and notably the sustainability, with strikingly no mention of resiliency, of the product or process brought to scale. Finally, many definitions in our analysis revealed an emphasis on not one, but a combination of Interventions, Mechanisms, or Outcomes, leading to further ambiguity.

In light of the literature and above categorization of terms, we contend that the continued uncertainty of scaling up is in part often related to the conflation of the noun, scale, and verb, to scale. Interpretation of scaling up that stresses product or process success, or outcomes is a function of the noun, scale. By contrast, where scaling up emphases reside in adaptation, expansion, geographical spread, or process, these descriptions are rooted in the meaning of the verb, to scale. Working to emphasize and separate the critical functions of scaling, we have presented a conceptual framework that operates in three stages: (1) Defining objectives and creating indicators; (2) Scaling efforts either by a new or existing innovation; and (3) Final measurement of outcomes. The novelty of this model lies in both its separation of scaling up and its associated actions based on the process (verb) and outcomes (noun). Where scaling up has traditionally occurred irrespective of M&E, our model works to showcase the critical role of M&E for both the innovation and development scaling up efforts. Scaling up and M&E are inextricably linked. Given this relationship and the evolution of M&E, future work could consider critically analyzing the variation in meaning of scale, by institution over time. Further, presenting commonalities and discrepancies in meaning between institutions and consideration on how these conceptions of scale influence development interventions.

Scaling up product or processes in targeting food security challenges is a vital component to developing sustainable solutions to the global hunger crisis across geographical scales. As such, a consensus on the ontological meaning of scaling up across institutions working towards these solutions is critical. Our aim in developing this model is to engender further consideration on the precision of scaling up terminology when working to bring a product or process to scale. Uncertainty on the meaning of scaling up should not be a barrier to meeting the critical needs being addressed through development interventions. Where there is ontological agreement on scaling up within and across R&D and NRM institutions, there is a higher likelihood for project success.