A Moderated Mediation Model for Board Diversity and Corporate Performance in ASEAN Countries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Board Diversity and Corporate Performance

2.2. Board Diversity and CSRR

3. Hypothesis Development

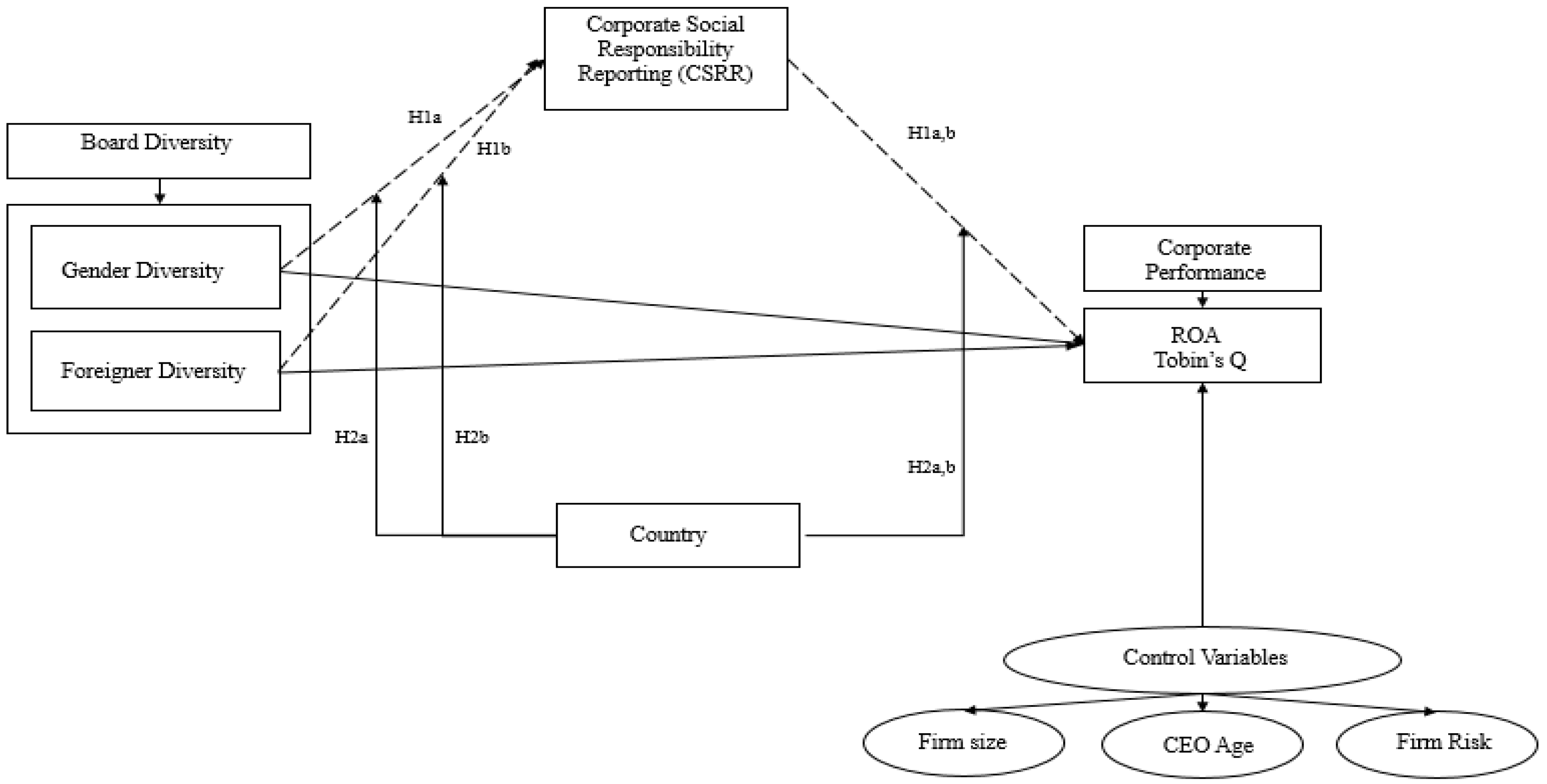

3.1. Integrating Board Diversity, Corporate Performance and CSRR as a Mediator

3.2. Moderated Mediation Effect of Country

4. Method

Sample and Procedures

5. Measures

5.1. Research Model

5.2. Model Specification of the Link between CSRR, CG, and Corporate Performance

5.2.1. Independent Variables

5.2.2. Dependent Variable

5.2.3. Mediator

5.2.4. Moderated Mediation

5.2.5. Control Variables

6. Analysis

6.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

6.2. Discriminant Validity

6.3. Convergent Validity

6.4. Reliability

6.5. Descriptive Statistics

6.6. SEM Results

6.7. Additional Analysis

7. Discussion and Implication

8. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marsiglia, E.; Falautano, I. Corporate social responsibility and sustainability challenges for a Bancassurance Company. Geneva Pap. Risk Insur. Issues Pract. 2005, 30, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.; Rao, K.; Tilt, C.; Tilt, C. Board diversity and CSR reporting: An Australian study. Meditari Account. Res. 2016, 24, 182–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshareef, M.N.Z.; Sandhu, K. Integrating Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) into Corporate Governance Structure: The Effect of Board Diversity and Roles—A Case Study of Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2015, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shleifer, A.; Vishny, R.W. A survey of corporate governance. J. Financ. 1997, 52, 737–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Knippenberg, D.; De Dreu, C.K.; Homan, A.C. Work group diversity and group performance: An integrative model and research agenda. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, N.A.; Angelidis, J.P. The corporate social responsiveness orientation of board members: Are there differences between inside and outside directors? J. Bus. Ethics 1995, 14, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafsi, T.; Turgut, G. Boardroom diversity and its effect on social performance: Conceptualization and empirical evidence. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 112, 463–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.; del Carmen Triana, M. Demographic diversity in the boardroom: Mediators of the board diversity–firm performance relationship. J. Manag. Stud. 2009, 46, 755–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galia, F.; Zenou, E. Board composition and forms of innovation: Does diversity make a difference? Eur. J. Int. Manag. 2012, 6, 630–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosvold, J.; Brammer, S.; Rayton, B. Board diversity in the United Kingdom and Norway: An exploratory analysis. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2007, 16, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadeo, J.D.; Soobaroyen, T.; Hanuman, V.O. Board composition and financial performance: Uncovering the effects of diversity in an emerging economy. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 105, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, D.A.; Simkins, B.J.; Simpson, W.G. Corporate governance, board diversity, and firm value. Financ. Rev. 2003, 38, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K.; Mínguez-Vera, A. Gender diversity in the boardroom and firm financial performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 83, 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelechowski, D.D.; Bilimoria, D. Characteristics of women and men corporate inside directors in the US. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2004, 12, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukl, G.; Gordon, A.; Taber, T. A hierarchical taxonomy of leadership behavior: Integrating a half century of behavior research. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2002, 9, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G. Responsible Management in Asia: Perspectives on CSR; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, N. Party quotas and rising women politicians in Singapore. Politics Gend. 2015, 11, 196–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S.; Huse, M. The contribution of women on boards of directors: Going beyond the surface. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2010, 18, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Z.; Abdullah, N.M.H.; Roslan, S. Capital structure effect on firms performance: Focusing on consumers and industrials sectors on Malaysian firms. Int. Rev. Bus. Res. Pap. 2012, 8, 137–155. [Google Scholar]

- Salvioni, D.M.; Gennari, F.; Bosetti, L. Sustainability and Convergence: The Future of Corporate Governance Systems? Sustainability 2016, 8, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienes, D.; Velte, P. The impact of supervisory board composition on CSR reporting. Evidence from the German two-tier system. Sustainability 2016, 8, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.; Rossi, A.; Tarquinio, L.; Tarquinio, L. An analysis of sustainability report assurance statements: Evidence from Italian listed companies. Manag. Audit. J. 2017, 32, 578–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilburn, K.; Wilburn, R. Using global reporting initiative indicators for CSR programs. J. Glob. Responsib. 2013, 4, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingwerth, K. The New Transnationalism: Transnational Governance and Democratic Legitimacy; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, C.A.; McNicholas, P. Making a difference: Sustainability reporting, accountability and organisational change. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2007, 20, 382–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, A.; Muir, C.; Hoque, Z. Measurement of sustainability performance in the public sector. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2014, 5, 46–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KPMG. KPMG International Survey of Corporate Responsibility Reporting 2011; KPMG: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Global Reporting Initiative. Equator Principles. Power. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/information/news-and-press-center/newsarchive/Pages/2016.aspx (accessed on 7 January 2016).

- Corporate Social Responsibility Asia; Lloyd’s Register Quality Assurance Limited. CSR in Asia the Real Picture; Corporate Social Responsibility Asia: Singapore; Lloyd’s Register Quality Assurance Limited: London, UK, 2010; Available online: www.csr-asia.com/publication.php (accessed on 7 January 2016).

- Waagstein, P.R. The mandatory corporate social responsibility in Indonesia: Problems and implications. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 98, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapple, W.; Moon, J. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) in Asia: A seven-country study of CSR web site reporting. Bus. Soc. 2005, 44, 415–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jizi, M.I.; Salama, A.; Dixon, R.; Stratling, R. Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility disclosure: Evidence from the US banking sector. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, S.; Miller, M.; Kusyk, S. How relevant is corporate governance and corporate social responsibility in emerging markets? Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2011, 11, 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzingai, I.; Fakoya, M.B. Effect of Corporate Governance Structure on the Financial Performance of Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE)-Listed Mining Firms. Sustainability 2017, 9, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S.A.; Graves, S.B. The corporate social performance-financial performance link. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntim, C.G.; Soobaroyen, T. Corporate governance and performance in socially responsible corporations: New empirical insights from a Neo-Institutional framework. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2013, 21, 468–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haniffa, R.; Hudaib, M. Corporate governance structure and performance of Malaysian listed companies. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 2006, 33, 1034–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schadewitz, H.; Niskala, M. Communication via responsibility reporting and its effect on firm value in Finland. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2010, 17, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; Safieddine, A.M.; Rabbath, M. Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility synergies and interrelationships. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2008, 16, 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, L.; Roberts, R.W. Corporate social performance, financial performance and institutional ownership in Canadian firms. Account. Forum 2007, 31, 233–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catanzariti, J.; Lo, M. Corporate Governance Changes Focus on Diversity. Available online: https://www.claytonutz.com/knowledge/2011/may/corporate-governance-changes-focus-on-diversity (accessed on 11 May 2011).

- Erhardt, N.L.; Werbel, J.D.; Shrader, C.B. Board of director diversity and firm financial performance. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2003, 11, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrader, C.B.; Blackburn, V.B.; Iles, P. Women in management and firm financial performance: An exploratory study. J. Manag. Issues 1997, 9, 355–372. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, T.; Jung, D.K. Corporate governance change and performance: The roles of traditional mechanisms in France and South Korea. Scand. J. Manag. 2015, 31, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protasovs, I. Board Diversity and Firm’s Financial Performance: Evidence from South-East Asia. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chuanrommanee, W.; Swierczek, F.W. Corporate governance in ASEAN financial corporations: Reality or illusion? Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2007, 15, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh, M. Corporate Governance and Executive Remuneration in Malaysia. Life Sci. J. 2013, 10, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Bear, S.; Rahman, N.; Post, C. The impact of board diversity and gender composition on corporate social responsibility and firm reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinnicombe, S. Women on Corporate Boards of Directors: International Research and Practice; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, Y.R.K. The ethics of corporate governance: An Asian perspective. Int. J. Law Manag. 2009, 51, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, P. Going green: Women entrepreneurs and the environment. Int. J. Gender Entrep. 2010, 2, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setó-Pamies, D. The relationship between women directors and corporate social responsibility. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2015, 22, 334–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, R.; Hj Zainuddin, Y.; Haron, H. The relationship between corporate social responsibility disclosure and corporate governance characteristics in Malaysian public listed companies. Soc Responsib. J. 2009, 5, 212–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado-Lorenzo, J.M.; Garcia-Sanchez, I.M. The role of the board of directors in disseminating relevant information on greenhouse gases. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 391–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R.; Owen, D.; Adams, C. Accounting & Accountability: Changes and Challenges in Corporate Social and Environmental Reporting; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, W.R. The adolescence of institutional theory. Adm. Sci. Q. 1987, 32, 493–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Muttakin, M.B.; Siddiqui, J. Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility disclosures: Evidence from an emerging economy. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggart, N.W. Explaining Asian economic organization. Theor. Soc. 1991, 20, 199–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zattoni, A.; Cuomo, F. Why adopt codes of good governance? A comparison of institutional and efficiency perspectives. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2008, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.J. Corporate social performance revisited. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 691–718. [Google Scholar]

- Adnan Khurshid, M.; Al-Aali, A.; Ali Soliman, A.; Mohamad Amin, S. Developing an Islamic corporate social responsibility model (ICSR). Compet. Rev. 2014, 24, 258–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Rucker, D.D.; Hayes, A.F. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2007, 42, 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hackston, D.; Milne, M.J. Some determinants of social and environmental disclosures in New Zealand companies. Account. Audit. Account. J. 1996, 9, 77–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S. Board size and the variability of corporate performance. J. Financ. Econ. 2008, 87, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, J.B.; Sundgren, A.; Schneeweis, T. Corporate social responsibility and firm financial performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1988, 31, 854–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, L.R.; Brett, J.M. Mediators, moderators, and tests for mediation. J. Appl. Psychol. 1984, 69, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeghal, D.; Ahmed, S.A. Comparison of social responsibility information disclosure media used by Canadian firms. Account. Audit. Account. J. 1990, 3, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tuwaijri, S.A.; Christensen, T.E.; Hughes, K.E. The relations among environmental disclosure, environmental performance, and economic performance: A simultaneous equations approach. Account. Org. Soc. 2004, 29, 447–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooks, J.; van Staden, C.J. Evaluating environmental disclosures: The relationship between quality and extent measures. Br. Account. Rev. 2011, 43, 200–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, M.; Jaggi, B. Global warming, commitment to the Kyoto protocol, and accounting disclosures by the largest global public firms from polluting industries. Int. J. Account. 2005, 40, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skouloudis, A.; Evangelinos, K.; Kourmousis, F. Development of an evaluation methodology for triple bottom line reports using international standards on reporting. Environ. Manag. 2009, 44, 298–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hambrick, D.C.; Geletkanycz, M.A.; Fredrickson, J.W. Top executive commitment to the status quo: Some tests of its determinants. Strateg. Manag. J. 1993, 14, 401–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Siguaw, J.A.; Cadogan, J.W. Export peformance: The impact of cross-country export market orientation. In Proceedings of the AMA Winter Educators’ Conference, Chicago, IL, USA, 12 June 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle, J. Amos Users’ Guide, version 3.6; Marketing Division, SPSS Incorporated: Chicago, IL, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Barki, H.; Hartwick, J. Interpersonal conflict and its management in information system development. Mis Q. 2001, 25, 195–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, J.E.; Deshon, R.P.; Bergh, D.D. Decision points for mediational type inferences in organizational behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 2006, 27, 1031–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.R.; Lambert, L.S. Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Fairchild, A.J.; Fritz, M.S. Mediation analysis. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 593–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueredo, A.J.; Garcia, R.A.; Cabeza De Baca, T.; Gable, J.C.; Weise, D. Revisiting mediation in the social and behavioral sciences. J. Methods Meas. Soc. Sci. 2013, 4, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizul Islam, M.; Deegan, C. Motivations for an organisation within a developing country to report social responsibility information: Evidence from Bangladesh. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2008, 21, 850–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C.J.; Gardberg, N.A.; Sever, J.M. The Reputation QuotientSM: A multi-stakeholder measure of corporate reputation. J. Brand Manag. 2000, 7, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Models | ||

|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| IV | Gender Diversity, Foreigner Diversity | Gender Diversity, Foreigner Diversity |

| DV | Corporate Performance | Corporate Performance |

| Controls | Firm Risk, Firm Risk, CEO Age | Firm Risk, Firm Risk, CEO Age |

| Mediator (CSRR) | yes | yes |

| Moderator (Country) | no | yes |

| Goodness of Fit Index | Research Models | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cut off Value | M1 | M2 | |

| df | positive | 37 | 64 |

| p-Value | ≥0.05 | 0.236 | 0.123 |

| RMSEA | ≤0.08 | 0.024 | 0.028 |

| GFI | ≥0.90 | 0.975 | 0.954 |

| CFI | ≥0.90 | 0.964 | 0.967 |

| RChisq/df | ≤2.00 | 1.157 | 1.207 |

| Total Result | good | good | good |

| Convergent Validity | Discriminant Validity | Reliability | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR > 0.7 | MSV < AVE | α > 0.7 | |||

| CR > AVE | ASV < AVE | CR > 0.7 | |||

| Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE | MSV | ASV | |

| Gender Diversity | 0.876 | 0.798 | 0.663 | 0.547 | 0.187 |

| Foreigner Diversity | 0.918 | 0.941 | 0.763 | 0.723 | 0.342 |

| ROA | 0.787 | 0.663 | 0.646 | 0.234 | 0.155 |

| Tobin’s Q | 0.814 | 0.826 | 0.720 | 0.654 | 0.379 |

| CSRR | 0.898 | 0.847 | 0.734 | 0.679 | 0.329 |

| Number | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROA | 264 | −0.16 | 0.41 | 0.0973 | 0.08705 |

| Tobin’s Q | 264 | 0.45 | 9.77 | 3.7061 | 2.04196 |

| gender | 264 | 0.00 | 0.500 | 0.1013 | 0.10983 |

| foreigner | 264 | 0.00 | 0.71 | 0.2179 | 0.18419 |

| CEO age | 264 | 1.58 | 1.68 | 1.7279 | 0.04925 |

| SIZE | 264 | 0.26 | 1.05 | 0.8750 | 0.10998 |

| CSRR level | 264 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 1.8631 | 0.71801 |

| Country | 264 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 2.4373 | 1.06419 |

| Board Diversity (X) CSRR (M) Corporate Performance (Y) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Effect | Indirect Effect | Direct Effect | ||||||

| Hypo | Description | P.Co | p-Value | P.Co | p-Value | P.Co | p-Value | Relationship Conclusions |

| H1 | Gender→ ROA | 0.531 | 0.041 * | 0.481 | 0.029 * | 0.572 | 0.042 * | Partial Supported |

| H2 | Foreigner→ ROA | 0.872 | 0.013 * | 0.664 | 0.005 * | 0.915 | 0.068 | Full Supported |

| Description | P.Co | p-Value | P.Co | p-Value | P.Co | p-Value | Relationship Conclusions | |

| CEO age | CEO age→ ROA | −0.533 | 0.031 * | 0.442 | 0.864 | −0.564 | 0.564 | Direct |

| Firm Size | Size→ ROA | 0.262 | 0.023 * | −0.453 | 0.264 | 0.336 | 0.336 | Direct |

| Firm Risk | Risk→ ROA | −0.756 | 0.214 | 0.000 | 0.0 | −0.821 | −0.821 | No |

| R Square (ROA) 0.245 R Square (CSRR) 0.403 | ||||||||

| Board Diversity (X) CSRR (M) Corporate Performance (Y) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Effect | Indirect Effect | Direct Effect | ||||||

| Hypo | Description | P.Co | p-Value | P.Co | p-Value | P.Co | p-Value | Relationship Conclusions |

| H1 | Gender→ Tobin’s Q | 0.234 | 0.009 * | 0.451 | 0.005 * | 0.289 | 0.006 * | Partial Supported |

| H2 | Foreigner→ Tobin’s Q | 0.312 | 0.410 | 0.516 | 0.005 * | 0.312 | 0.068 | Indirect Supported |

| Description | P.Co | p-Value | P.Co | p-Value | P.Co | p-Value | Relationship Conclusions | |

| CEO age | CEO age→ ROA | 0.255 | 0.017 * | −0.151 | 0.231 | 0.274 | 0.019 * | Direct |

| Firm Size | Size→ ROA | 0.296 | 0.161 | −0.146 | 0.049 * | 0.276 | 0.171 | Indirect |

| Firm Risk | Risk→ ROA | −0.212 | 0.851 | 0.285 | 0.216 | −0.289 | 0.643 | No |

| R Square (ROA) 0.278 R Square (CSRR) 0.512 | ||||||||

| Hypothesis | Malaysia | Indonesia | Singapore | Philippines | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3 (with ROA) | Supported (Partial Mediation) | Supported (Partial Mediation) | Rejected | Rejected | There is a difference with moderator (accepted) |

| H4 (with ROA) | Rejected | Supported (Partial Mediation) | Supported (Partial Mediation) | Rejected | There is a difference with moderator (accepted) |

| H3 (with Tobin’s Q) | Rejected | Supported (Partial Mediation) | Rejected | Rejected | There is a difference with moderator (accepted) |

| H4 (with Tobin’s Q) | Rejected | Rejected | Supported (Full Mediation) | Rejected | There is a difference with moderator (accepted) |

| Testing Path | S.E | β | Sig |

|---|---|---|---|

| Path c DV = ROA | |||

| IV = gender | 0.048 | 0.532 | 0.035 |

| Path a DV = CSRR | |||

| IV = gender | 0.0937 | 0.248 | 0.001 |

| Path b and c’ DV = ROA | |||

| IV = gender | 0.035 | 0.320 | 0.049 |

| IV = CSRR | 0.023 | 0.432 | 0.021 |

| Total (a)*(b) | 0.110 | ||

| Testing Path | S.E | β | Sig |

|---|---|---|---|

| Path c DV = ROA | |||

| IV = foreigner | 0.048 | 0.465 | 0.035 |

| Path a DV = CSRR | |||

| IV = foreigner | 0.423 | 0.815 | 0.001 |

| Path b and c’ DV=ROA | |||

| IV = foreigner | - | - | Not Sig |

| IV = CSRR | 0.3221 | 0.342 | 0.014 |

| Total (a)*(b) | 0.278 | ||

| Testing Path | S.E | β | Sig |

|---|---|---|---|

| Path c DV = Tobin’s Q | |||

| IV = gender | 1.351 | 0.221 | 0.003 |

| Path a DV = CSRR | |||

| IV = gender | 0.0937 | 0.248 | 0.001 |

| Path b and c’ DV = Tobin’s Q | |||

| IV = gender | 1.123 | 0.164 | 0.000 |

| IV = CSRR | 0.093 | 0.229 | 0.043 |

| Total (a)*(b) | 0.057 | ||

| Testing Path | S.E | β | Sig |

|---|---|---|---|

| Path c DV = Tobin’s Q | |||

| IV = foreigner | - | - | Not Sig |

| Path a DV = CSRR | |||

| IV = foreigner | 0.423 | 0.815 | 0.001 |

| Path b and c’ DV=Tobin’s Q | |||

| IV = foreigner | - | - | Not Sig |

| IV = CSRR | 0.156 | 0.324 | 0.023 |

| Total (a)*(b) | 0.264 | ||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

E-Vahdati, S.; Zulkifli, N.; Zakaria, Z. A Moderated Mediation Model for Board Diversity and Corporate Performance in ASEAN Countries. Sustainability 2018, 10, 556. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020556

E-Vahdati S, Zulkifli N, Zakaria Z. A Moderated Mediation Model for Board Diversity and Corporate Performance in ASEAN Countries. Sustainability. 2018; 10(2):556. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020556

Chicago/Turabian StyleE-Vahdati, Sahar, Norhayah Zulkifli, and Zarina Zakaria. 2018. "A Moderated Mediation Model for Board Diversity and Corporate Performance in ASEAN Countries" Sustainability 10, no. 2: 556. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020556

APA StyleE-Vahdati, S., Zulkifli, N., & Zakaria, Z. (2018). A Moderated Mediation Model for Board Diversity and Corporate Performance in ASEAN Countries. Sustainability, 10(2), 556. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020556