1. Introduction

The proliferation of multi-stakeholder participation (MSP) is one of the most significant and studied changes in global governance of the past three decades. Such arrangements have been analyzed in a wide variety of areas assuming distinct terminologies, such as multi-stakeholder partnerships, platforms, networks, processes and approaches [

1,

2]. Despite their differences, these initiatives aim to integrate a variety of actors in collective decision-making, usually categorized under labels along the spectrum of public/governments, private sector organizations and civil society. Empirical studies have focused on the performance of these initiatives [

3,

4,

5], while others have discussed their political implications in relation to their potential to expand participation, reduce the exclusive nature of the international system and provide for enhanced accountability of global policy-making [

6,

7,

8]. Proponents argue that, ideally, such MSP arrangements represent forms of deliberative democracy at the international level that could contribute to overcoming the international systems’ undemocratic decision-making and related problems of legitimacy [

9,

10,

11], while others have criticized the very same potential of MSP from different angles [

12,

13].

A growing body of empirical work analyzes such arrangements in terms of processes, outputs or discourses [

4,

14], putting principles such as inclusion, transparency and accountability at the center of analysis. However, there is still much to be explored around the nuances and deliberative qualities of such MSP arrangements, including their ambiguities and dynamics.

This raises the question: how to analyze the extent and ways MSP is improving the deliberative quality of processes and institutions of global governance? The reasoning behind this question is to neither fully embrace, nor disregard MSP, but rather explore more deeply the specifics of these arrangements, with the aim of contributing to a heuristic framework of how MSP contributes to the deliberative quality of the international system.

To address this question, we apply Dryzek’s deliberative system framework [

15,

16,

17] to one United Nations’ Committee where multi-stakeholder participation features prominently: The Committee on World Food Security (CFS). The case of the CFS seems particularly fitting for analysis from the viewpoint of deliberative theory. Since it was reformed in 2009, the Committee has aspired to be a central global institution for policy debate on food security.

Data were collected through: (i) participant observation at the 42nd and the 43rd Plenary Sessions of the CFS (October 2015 and October 2016) and at the Second and Third meetings of the Open-Ended Working Group on the Sustainable Development Goals (February 2016 and March 2016); this included several different events that ran in parallel with the official agenda; (ii) 20 semi-structured interviews with key informants (6 with government representatives, 6 with civil society, 6 with private sector, 2 with international organizations; see

Appendix B for more information); (iii) numerous informal exchanges between the authors and participants of those meetings.

Our findings show that CFS’s deliberative quality is mixed. On the one hand, the CFS improves the deliberative capacity of food security governance by including and facilitating the transmission of a wide representation of discourses from the public to the empowered spaces. At the same time, the deliberative process suffers from poor performance in the areas of accountability and meta-deliberation and limits the capacity for CFS’s outcomes to achieve high adoption at national and local levels. The growing body of literature analyzing the CFS suggests that the lack of deliberative quality in the areas of accountability and meta-deliberation relate back to power asymmetries [

18]. Therefore, we argue, the use of Dryzek’s heuristic framework of a deliberative system would benefit from more explicit consideration of the different forms of power that play a central part in the social relations between the actors involved [

19]. One promising possibility would be to explicitly investigate how power asymmetries influence transmission, accountability and decisiveness. By proposing this analytical exercise, we expect to advance a heuristic framework for assessing deliberation in MSP that could be useful in the context of the growing importance of this instrument in sustainable development and global governance.

The paper proceeds as follows.

Section 2 reviews the literature on MSP and deliberative theory and introduces the analytical categories of Dryzek’s deliberative system framework.

Section 3 applies this framework to CFS. The paper concludes with a synthesis of heuristic and empirical observations (

Section 4).

2. MSP and Deliberation: Towards a Heuristic Framework

The consolidation of multi-stakeholder participation in global policy-making occurs in parallel with a “deliberative turn” in political sciences and democratic theory in the past two decades. This section briefly reviews this literature and then introduces Dryzek’s deliberative systems framework and the value of using it for assessing MSP.

2.1. MSP: From Experimental Trend to Mainstream

In global environmental governance, the emergence of MSP as a fundamental approach to intergovernmental policy-making can be traced to the UN Earth Summit, held in Rio in 1992 (Eco 1992). In this period, MSP approaches had already provided a major tool for fostering rural development at subnational to local levels, linked to approaches covered under Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA) [

20], where stakeholder platforms were conceived as a tool for rooting governmental policy-making more coherently to the visions, expectations and needs of “the people”.

Eco 1992 brought these experiments to the global stage, particularly through the recognition of NGOs by the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) [

21]. This trend became firmly established at the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) in 2002 in Johannesburg; Rio+20 in 2012; and the recent negotiations of the Sustainable Development Goals. In the latter, MSP features prominently as one of the key approaches for internally governing the implementation of the 2030 Agenda.

The debate on the nature of MSP covers empirical, as well as theoretical aspects. One thread of debate concerns the degree to which MSP in practice leads to measurable outcomes assigned to it by the promoters of such governance instruments, for example, if global environmental standards or voluntary guidelines for business generated by arrangements with MSP are in effect being used by the actors that participated in their construction [

3]. Empirical studies have examined the types, scopes and effectiveness of policies developed through MSP. The general tendency indicates limited effectiveness, as demonstrated by Pattberg et al. [

14], who analyzed 340 initiatives with MSP related to the implementation of the WSSD.

As a starting point, efforts to theorize global governance co-emerged with the increased importance of non-state actors in global politics since the 1990s. Proponents of including non-state actors in international organization and global governance tend to argue that (potentially) this constitutes a change that could be useful to counteract structural flaws in existing settings of international governance and multilateral institutions [

9]. It is argued that the inclusion of non-state actors might counteract the often undemocratic nature and legitimacy deficit of international politics, addressing long-term institutional problems of access, transparency and responsiveness [

10]. The inclusion of non-state actors, so the argument goes, addresses these legitimacy issues by changing the composition of actors towards more democratic procedures of representation and decision-making than the nation state-based system. In this view, this would ultimately lead to a higher degree of accountability by responsible actors and organizations [

11,

22]. Other proponents of multi-stakeholder participation in institutions and processes of global governance emphasize that non-state actor participation can also yield expert-driven decision-making as a source of input and outcome legitimacy [

23] and improve problem-solving capacity in global governance processes by sharing information and expertise [

24].

Critical theorists have come to challenge the comparatively liberal arguments presented above. They maintain that multi-stakeholder participation constitutes a form of liberalization that is not inherently a quick fix for democratizing global governance [

12,

25]; on the contrary, the undemocratic, unrepresentative and unaccountable features of existing international organizations offer little prospect for this [

26]. Critical assessments perceive MSP in global governance as a highly ambiguous development, dubiously concealing asymmetric dependencies [

13], inhibiting civil society critical contributions, as in “NGO contract fever” [

27], or in social movement co-optation [

28]. Other critical studies have elaborated on specific conditions needed in MSP to fulfil its potential to improve the deliberative quality of global governance. These would include the possibility that emergent critical discourses encounter public authority [

29]; and that weaker actors that carry those discourses be able to influence decision-making, thus acquiring more than just the formal right to participate [

30]. Other critiques contest the potential of MSP to reshape citizen and state relations, even under ideal conditions, implying that marginalized groups have no agency in contemporary processes of global governance [

31].

2.2. Deliberation Theory in a Nutshell

The literature above remains inconclusive on whether and to what degree the recent rise of multi-stakeholder participation contributes to improving the deliberative quality of global governance. For our following assessment, it is important to be aware of the framings and critiques voiced in political theory described in the previous section and to consider case-specific analysis of MSP. Deliberation theory offers elements to identify whether MSP enables progress toward this ideal by providing concepts for a sound and theoretically-robust analysis that goes beyond solely assessing outcomes.

With antecedents dating back to Greek philosophy, deliberative theory has been considered throughout the past few decades in quite different fields of scientific inquiry [

32]. In some situations, its broad and diverse use led to stretching, imprecision and confusion of the concept. A theory of deliberation is explored in Habermas’ the Theory of Communicative Action [

33], in which he defined a “behaviour oriented towards reaching a common understanding”. According to Habermas, actors switching from strategic to communicative action would not lean towards maximizing their fixed preferences, as rational theory would predict, but rather towards seeking a common understanding of a given position. Consequently, this requires that actors are open to preference change if they encounter better arguments, a process that also depends on a series of pre-conditions.

When applying Habermas to international relations, Risse [

34] uses the concept of “argumentative rationality”, to define when actors do not completely reject the rational behavior assumption, but also do not simply bargain for their fixed preferences. This behavior would also contrast with rule-guided behavior employed by social constructivism, which argues that human agency only exists embedded (or constrained by) in structural conditions formed around the social environment, such as culture and institutions.

An increasing number of authors have since taken Habermas’ initial theoretical postulations closer to the real-world situation of everyday politics [

35,

36]. These efforts included addressing the existence of diversity and pluralism, socio-economic inequalities and power asymmetries that hinder access to voice discourses and difficulties in creating large-scale deliberation [

37]. Moreover, questions on institutional designs to cope with such complexities became central to deliberative democracy studies in the past few years [

38]. In a world of evident power asymmetries, some of the conditions for deliberation are difficult to achieve, particularly those that require equal opportunities to voice discourses.

2.3. Dryzek’s Deliberation System Framework

The core of our heuristic framework to study MSP builds on Dryzek’s formulation of a deliberative system, which substantiates three principles for achieving deliberation: authenticity, inclusiveness and consequentiality [

15,

17]:

- (a)

To be authentic, deliberation ought to: (i) be able to induce reflection upon preferences in a noncoercive fashion; (ii) involve communicating in terms that those who do not share one’s point of view can find meaningful and accept.

- (b)

To be inclusive, deliberation requires the opportunity and ability of all affected actors (or their representatives) to participate.

- (c)

To be consequential, deliberation must somehow make a difference when it comes to determining or influencing collective outcomes. Such outcomes might include laws and other explicit and codified public policy decisions, international treaties, the more informal outcomes reached by governance networks or even cultural change.

This formulation tries to address several issues raised in the literature on deliberation theory, such as whether deliberation needs to lead to consensus [

39]. Dryzek responds that “the purpose of deliberation is not to secure consensus. Instead, the key goal of deliberation is to produce meta-consensus that structures continued disputes” [

15]. Another critique refers to communication formats that do not follow the standards of reasoned argumentation, such as rhetoric and storytelling [

40]. Evidence suggests that, by focusing mostly on reasoning, deliberation “privilege[s] dominant groups” and might suppress minority views [

15,

32]. The discussion on the role of rhetoric is remarkable in this regard. Rhetoric can play an important role when employed by marginalized persons who do not necessarily possess the skills of rational argumentation. There are also cases in which powerful rhetoric helped bring issues that were not usually meaningfully represented to the center of a political system [

41]. However, the issue is not as simple as just accepting or disregarding any type of rhetoric, since history frequently reminds us how rhetoric can be a powerful tool for creating social division, fueling conflict and violence; and thus, the opposite of deliberation.

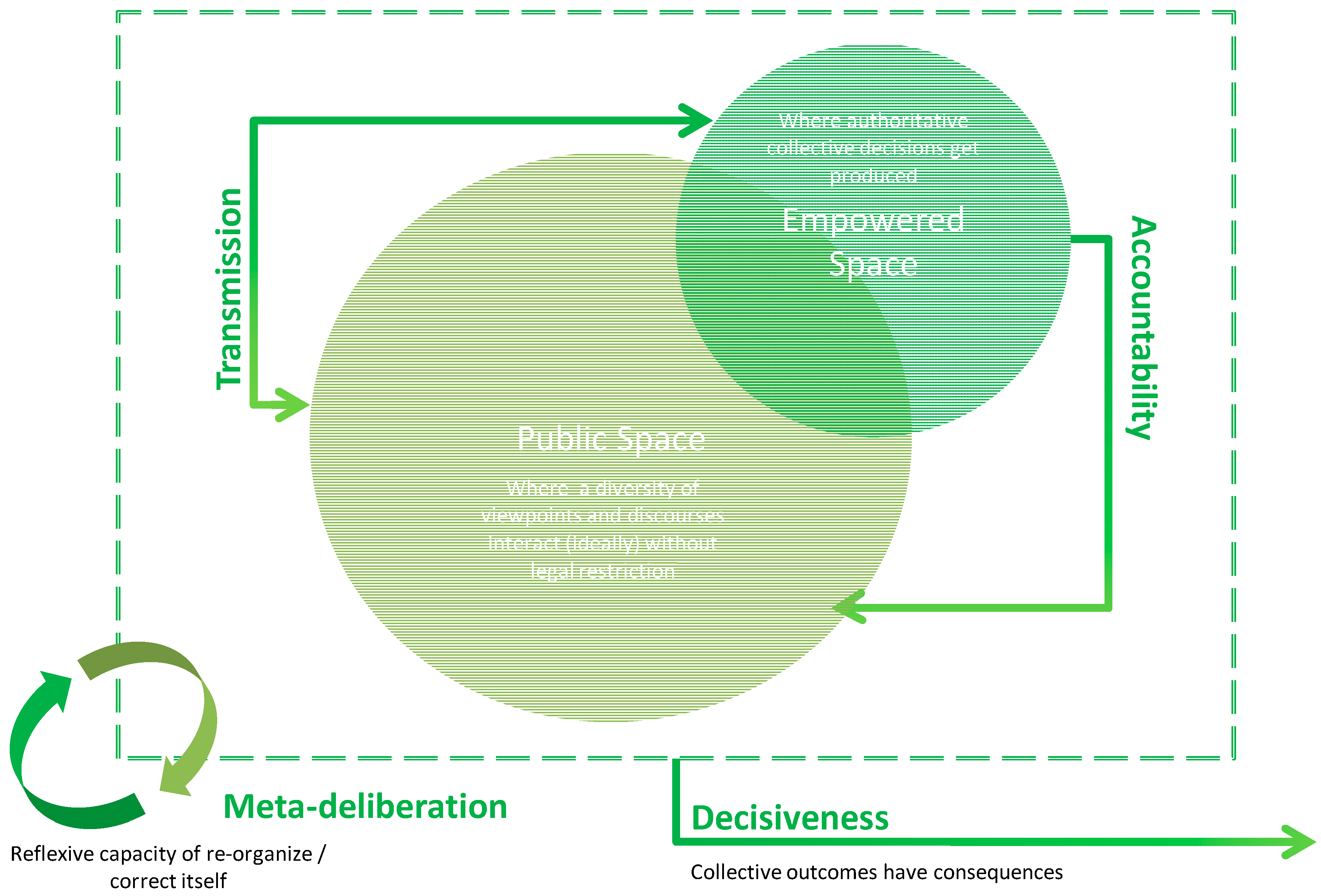

For operationalizing deliberative systems, Dryzek [

15] also offers an analytical framework (

Figure 1) that we use in our subsequent case study of deliberation in the CFS. The framework includes six elements to assess if a given system attends to the principles of authenticity, inclusiveness and consequentiality: (1) the existence of a public space, where a variety of discourses and wide-ranging communications take place, ideally with few barriers and legal restrictions; (2) the presence of an empowered space, which differentiates itself from the former by being a space where authoritative decisions are made; (3) transmission, understood as how deliberations in the public space influence those in the empowered space; (4) accountability, meaning mechanisms whereby actors pertaining to the empowered space give an account and justify their decisions and actions; (5) meta-deliberation, which is the reflexive capacity of the system as a whole to deliberate with its organization and reform if needed; and (6) decisiveness, understood as when the collective outcomes generated by the system cause consequences.

The framework does not conceptualize democracy from the perspective of the existence of particular institutions. This allows the researcher to apply the deliberation system framework to diverse political systems, from liberal democracies to single-party states, networks, and systems based on traditional authorities. In our application of Dryzek’s framework to study the deliberative quality of MSP at the CFS, we follow [

42,

43,

44], who applied the theory of deliberative systems to the analysis of global governance institutions.

Specifically, the application of Dryzek’s framework identifies four major flaws associated with governance initiatives based on multi-stakeholder participation: (i) that processes claiming to apply MSP generally fail to include all distinct groups and perspectives on the issue at stake; (ii) that MSP arrangements usually create unaccountable decision-making structures, especially on platforms without well-designed representation and participation rules, compared with other decision-making fora with more structured procedures for accountability reports; (iii) that MSP is often accompanied by un-reflexive decision-making structures, understood as the capacity of the system to identify problems in the decision-making process and formulating corrective strategies; and (iv) that most platforms based on MSP do not take into consideration the different forms of power in public participation, which is however a decisive component of the social relations of the actors involved.

Assessment of how participatory and inclusive MSP depends on the quality of the public and empowered spaces and the facilities permitting transmission between the two. That is, all discourses presented in the public space must also be able to infiltrate the empowered space. The most straightforward procedure consists of identifying and characterizing the different discourses that permeate the two spaces. This can be supplemented by analyzing the potential convergences, tensions and conflicts between them. Stakeholder mapping, where stakeholders are positioned according to their attachment of a particular discourse, can also provide orientation in assessing transmission.

As described previously, accountability is a crucial measure of whether the system is performing deliberatively. Accountability can be assessed by identifying formal and informal obligations between representatives and constituencies, as well as between higher and lower hierarchical bodies within organizations. These could include obligations towards information sharing, reporting and justification, among others, and should necessarily lead to an assessment of the level of transparency involved in these obligations, an essential element of accountability.

Within the deliberative framework, reflexivity correlates mostly with the elements of meta-deliberation. In other words, a deliberative system offers regular opportunities for its participants to analyze and discuss corrections in the decision-making procedures. Assessments of meta-deliberation could start by a time-scale analysis of the constitution and major decisions of a MSP. In particular, one should look for moments where participants receded from deciding on the issue itself and re-discussed the rules of engagement, for example, by reforming MSP governance rules. One could also investigate whether new feedback mechanisms were built into the reformed decision-making process.

Finally, while the conceptualization of power in MSP is challenging [

45], ignoring such an issue is inappropriate for treating MSP through an analytical lens, as power affects the capacity to effectively articulate, participate, represent, to hold accountable, among other factors. Clapp and Fuchs [

46] speak of three dimensions of power to analyze influence of powerful actors; in their case, corporates influencing global food governance: (i) instrumental; (ii) structural; and (iii) discursive power. While instrumental represents the direct influence achieved through political campaigning or lobby, structural power represents more indirect ways under which political options for certain actors are limited by more powerful ones even before bargaining starts, for example, by determining agenda-setting. Finally, discursive power is related to how the adoption of framings and world views of certain actors influence the formation of interests of other actors.

The deliberation system framework does not treat power asymmetries directly as one of its elements (as in the case of transmission, accountability and reflexivity), but it offers some ways of identifying them. One reason why power asymmetries are so central is because they can be the source of flaws in the three issues discussed above. That is, participants who lack the requisite capacities for addressing audiences and use the international technocratic language that permeates global negotiations might face constraints in organizing, voicing, and expressing their discourses, thus inhibiting truly inclusive MSP. Relating this to Clapp and Fuchs’ framework, the language that dominates negotiations would be an expression of the discursive and instrumental power. Furthermore, powerful representatives might not feel obliged to give an account of their actions, even to their constituencies. Furthermore, powerful participants might face disincentives to engage in reforming MSP rules, due to the risk of diminishing their capacity to influence decisions, thus reducing reflexivity. These two—denial of account and refuse of reform—would constitute expressions of structural power since they represent what should and what should not be part of the agenda. Additionally, even in systems with high levels of transmission, accountability and meta-deliberation, resolutions are not necessarily decisive; that is, the system might be jointly generating agreements that are not actually applied.

3. Results and Discussion: Deliberation and the Committee on World Food Security

To explore the applicability of deliberative theory to the assessment of MSP, we analyze evidence from the CFS. After a reform in 2009, which opened the Committee to more qualified participation of non-state actors, the CFS has tried to position itself as the “first and foremost inclusive platform” for addressing food governance globally. With almost a decade since this reform, this statement may sound over-enthusiastic, since the Committee suffers from well-known limitations in becoming the authoritative forum for global decision-making in an institutional landscape of global food governance that is characterized by institutional fragmentation [

47] and dominated by immense power asymmetries among actors [

18]. Still, without a doubt, the CFS’s reform did reposition the Committee in a much more prominent role in global food governance [

48].

Part of this growing recognition of CFS and claimed legitimacy follows the arguments of those promoting MSP as a way to improve deliberation and democratic choice in global governance. According to this line of reasoning, advancing MSP in global governance improves representation and contributes to expanded participation, inclusion and enhanced accountability. In fact, a vivid debate has ensued around these issues in the context of MSP at CFS [

49].

Brem-Wilson [

30] analyzed the engagement of a particular constituency, the global peasant movement and its most emblematic organization, La Vía Campesina (LVC), at the CFS, arguing that this encounter represents the case of a nascent transnational public sphere [

29]. In his analysis, LVC acts as an organized movement that articulates discourses and actions from affected publics within an institutionalized center of global decision-making; the CFS. However, the building of this transnational public sphere is not an automatic process, stresses the author, rather dependent on the fulfilment of certain requisites that translate the formal participation rights of affected publics into effective participation [

30,

50]. This reasoning that deliberation at CFS should imply more than the formality of being represented is also in line with the idea of meaningful participation, where consultations must be used to “guide and inform outcomes, and are not simply used to legitimize outcomes” ([

51], p. 150).

The conditions that allow expanded representation to translate into greater inclusivity at CFS has also been questioned by McKeon [

52], building on the differentiation between “multi-actor” and “multistakeholderism”. According to the author, while the first concept recognizes the different interests, roles, responsibilities and power resources of the parties, the former disregards those, for example, by diluting the distinction between “right-holders” (citizens, in the case of CFS, those affected by food insecurity) and “duty-bearers” (states) in international law within MSP arrangements. Recently, the Committee itself commissioned a study to its science-policy interface, the High-Level Panel of Experts (HLPE), about “Multistakeholder Partnerships to Finance and Improve Food Security and Nutrition in the Framework of the 2030 Agenda”. The background reasoning behind this request is related to the different understandings of how the CFS should position itself currently and in the future based on distinct interpretations of its 2009 reform blueprint [

49], as well as on its political capacity to assume centrality in the disputed and fragmented arena of global food governance.

Aiming to contribute to this debate, it seems valid to explore the applicability of deliberative theory in analyzing MSP using the case of the CFS. We start by characterizing actors and discourses at both the public and empowered spaces and cross analyzing the transmission between those. Then, we proceed by assessing accountability, meta-deliberation and decisiveness. Details on the mix-method package used to operationalize Dryzek’s deliberative system framework is provided in

Appendix A.

3.1. Characterization of Public and Empowered Spaces

One major step in characterizing public spaces starts by describing discourses that key actors reproduce. Comprehensive discourse analysis is beyond the scope of this article, considering its data intensity and length. While a complete discourse analysis can assist in illuminating factors that inhibit the transmission of discourses between public and empowered spaces, it offers less insights into the participation dynamics within MSP arrangements identified as key in the CFS-related literature. We prefer to present a simpler stylized content analysis based on analytical dichotomies of major discourses on food security, focusing on two dimensions that permeate numerous CFS debates: (i) food systems types; (ii) roles of states and market. Further, we support this with complementary analysis that refines the other essential elements of Dryzek’s framework: accountability, meta-deliberation and decisiveness.

To construct these analytical dichotomies, we reviewed key literature that employed similar approaches [

53,

54,

55] and coded and clustered content from the participant observations at Plenary Sessions and Open-Ended Working Groups mentioned in the Introduction, including official interventions, statements and web pages of all interviewed representatives and other key stakeholders. This provided enough elements for positioning actors active at the CFS within the range defined by the extremes of analytical dichotomies

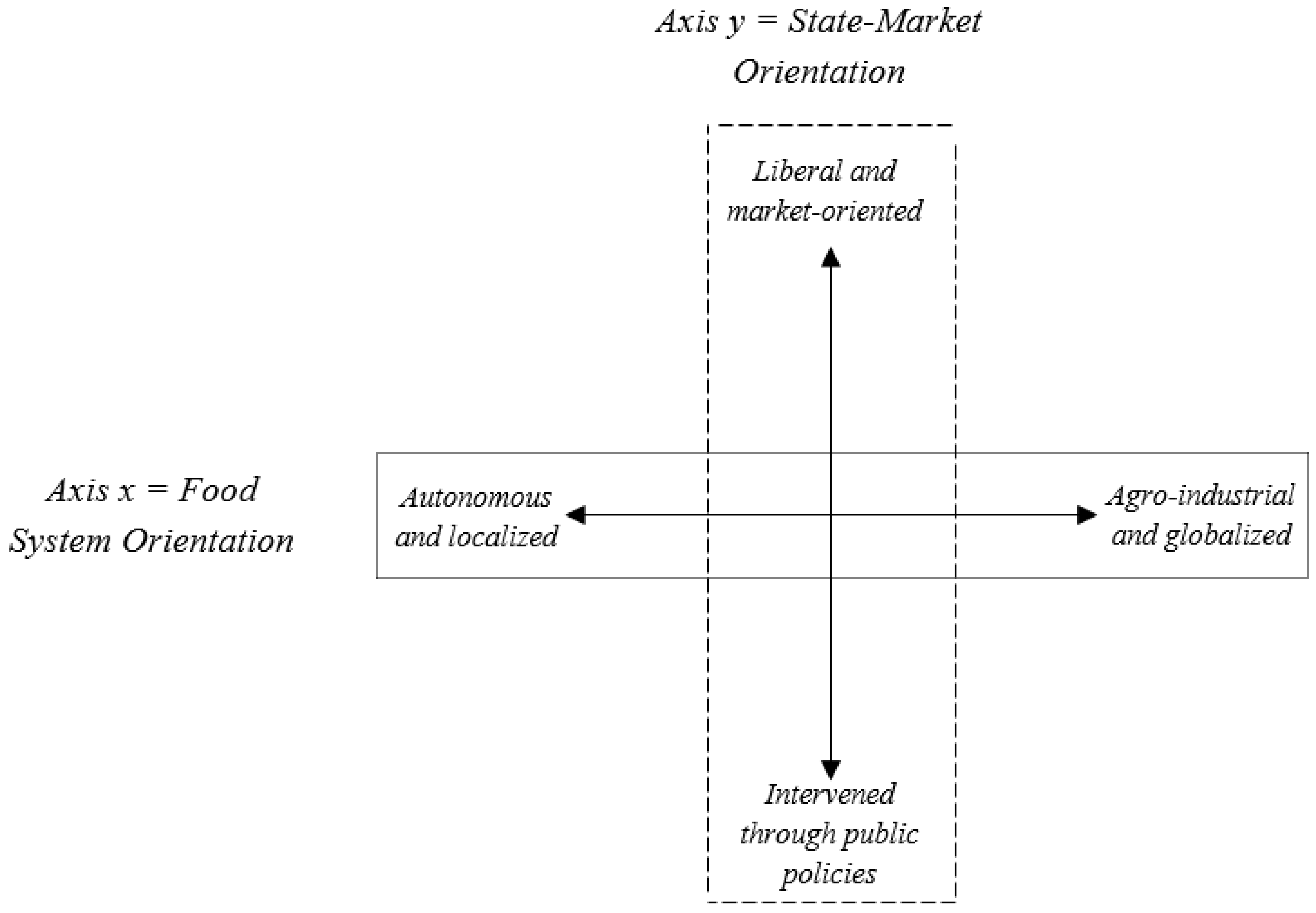

Considering the above, food security discourses can be categorized according to two dimensions as shown in

Figure 2.

Food system (axis x) refers to the distinct types of food systems that actors defend as the most appropriate to achieve food security. The extremes are:

Autonomous and localized: food systems composed of smaller production units, relatively autonomous in terms of labor and inputs. Whenever possible, input markets, processing and distribution are organized in short-circuits, but maintaining lower inputs usage and reduced food transportation. Consumers are generally close to production and processing stages, both in physical, as well as sociological terms, meaning consumers are interested in knowing food origins, their production sites and the actors participating in the food system. In terms of sustainability, agroecological agriculture [

56] has been increasingly identified with this food system perspective, as it shares focus on autonomy, reduced inputs’ use and fair relationships between actors across food systems;

Agro-industrial and globalized food systems represent vertically- and horizontally-integrated production systems, generally organized in larger production units. In these systems, economic efficiency tries to be optimized through industrial processes for standardized production. Labor is mostly hired, and inputs are mostly acquired in the market. Consumers can be close, but can also be located several thousand kilometers from production and processing sites, due to the lower transportation costs and lower preference from consumers on local food origins.

State-market orientation (axis y) refers to actor’s opinions on the role of states and markets in organizing food systems. The extremes are:

The liberal and market-led orientation considers the private-sector as the driver of agricultural growth and, ultimately, agricultural development. State intervention is relevant, but should be oriented toward facilitating private investments in economically-efficient agricultural activities. This can take the form of regulating (or de-regulating) labor and land markets, facilitating transactions, for example, by ensuring property rights, juridical security and lowering transaction costs. In this perspective, food security can be achieved by pursuing trade-oriented strategies, if trade is conducted with less barriers and more emphasis on economies of scale;

The intervened through public policies orientation does not disregard the importance of market forces in organizing agricultural production, processing and distribution. Nevertheless, it considers that markets constantly fail in their allocation role and that public policies are vital for orienting food systems. In this sense, the state, as the operator of public policies jointly negotiating with broader societal constituencies, continues to assume a regulatory role in similar terms as the liberal and market-led orientation, but assumes more active roles. These include: (i) providing rural public goods; (ii) protecting local production from international competition; (iii) supporting smallholder farmers with extensions, inputs and credit; (iv) protecting marginal farmers from land and resource expropriation; (v) reducing land concentration by agrarian reforms, among others. Trade can be an engine for complementing food security, but only if it “governed”, meaning when it does not come into contradiction or when it is used to support other government policies.

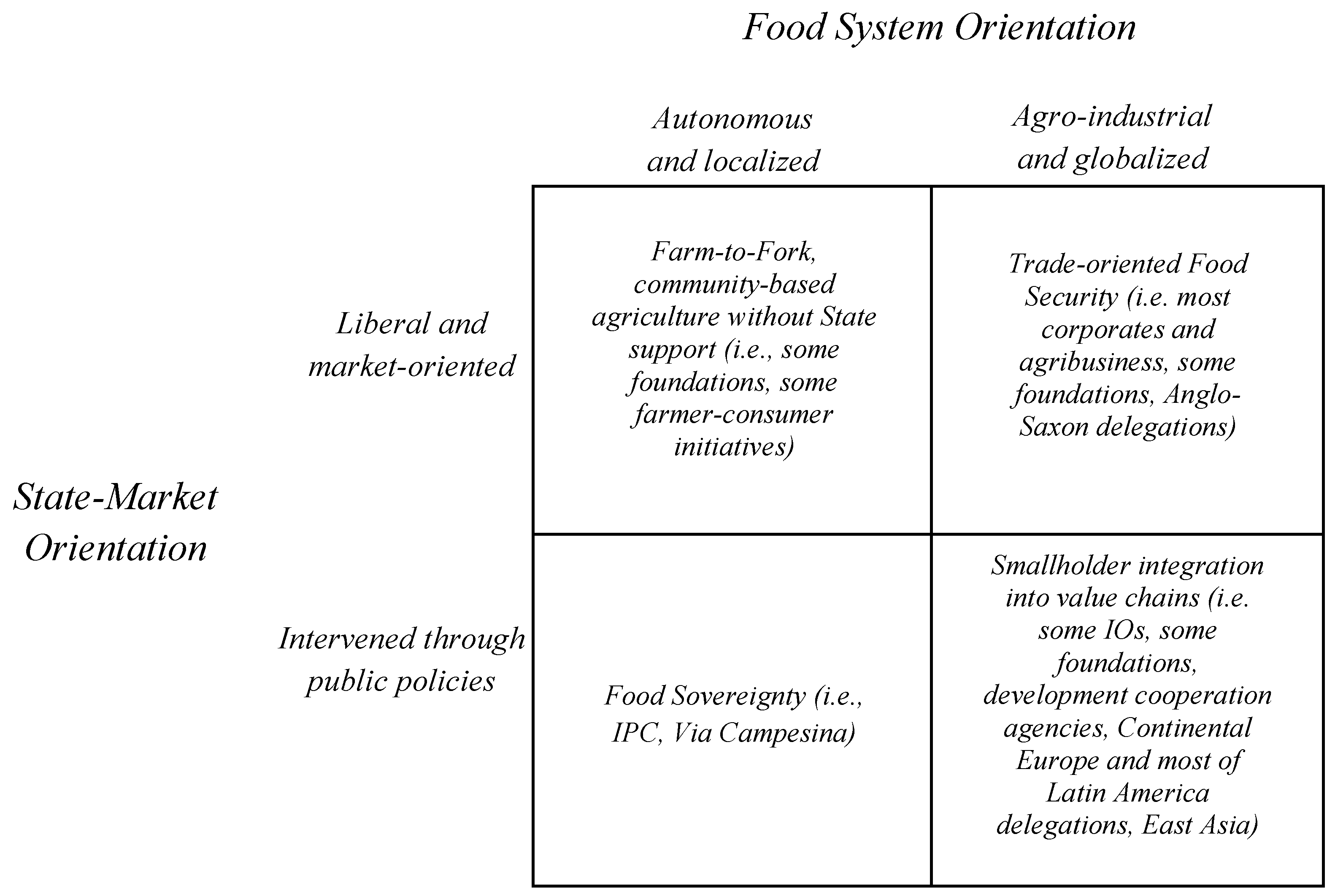

With this content analysis of food security discourses, it is possible to position certain actors that are active at the CFS along a matrix of the two dimensions, as shown in

Figure 3.

In the context of the CFS, the empowered space is the Committee itself. A detailed contextualization of this UN body and its important 2009 reform has been covered in recent literature [

48,

50,

57]. The institutional structure of CFS is similar to other UN committees: a plenary, where members discuss and make decisions; a bureau or chair, who sometimes represents the committee and propose decisions; and a secretariat, which facilitates the process. The Committee also counts the technical and scientific expertise supported by a body for scientific advice: the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE). There are however some important institutional innovations for understanding discursive representation and consequently the deliberative capacity of the Committee.

Its 2009 reform brought about two of these institutional innovations. The first is the active participation of non-state actors such as civil society, the peasant movement, the private sector, philanthropies, etc. (In its 2009 reform, the Committee was opened to participants of five categories of organizations: (i) UN agencies and bodies with specific mandates in the area of food security and nutrition; (ii) civil society and non-governmental organizations and their networks; (iii) international agricultural research systems; (iv) international and regional financial institutions; and (v) private sector associations and private philanthropic foundations ([

58], p. 6)). Non-state actors hold rights such as to intervene in plenaries, submit documents and contribute to intersessional activities. In principle, the only right that remains solely in the hands of the CFS members-states is the right to vote on final decisions. The second innovation is the facilitation of the participation of non-state actors in two autonomous and self-organized bodies, the Civil Society Mechanism (CSM), along with the Private Sector Mechanism (PSM).

The attendance during plenary meetings confirms this representation of a wide composition of actors. As an illustration, the CFS’s 42nd plenary (October 2015) was attended by 133 member-states; 6 states that were non-members of the Committee; 12 UN agencies; 98 civil society and non-governmental organizations, the vast majority of those through the CSM; 3 international agricultural research systems; 2 international financial institutions; 71 private sector associations and private philanthropic foundations, also the vast majority of those through the PSM; besides 42 observers and organizations not pertaining to the formal categories above.

In sum, the public space of food governance reveals discourses that can be broadly characterized as four categories, while in terms of formal representation, the empowered space of the CFS shows the substantial diversity of actors. The next sub-section looks at the transmission between those two spaces.

3.2. Transmission

Transmission refers to the processes through which discourses of the public space influence deliberation at the empowered space. This can be assessed by looking at three factors: (i) discourse representation: whether all discourses found in the public space are also found in the empowered space; (ii) if actors show signs of ideal deliberative procedure, meaning whether communication suggests truthfulness, respect and mutual justification without coercion and/or threats; and (iii) ability of actors to effectively participate and influence decisions. Discourse representation is a direct factor to consider when assessing transition since it can clearly show if the empowered space is closed to important discourse on the topic from the public sphere. This is key since actors that dominate the empowered space can be reluctant or resistant to considering more radical discourses. Truthfulness, respect and mutual justification in the empowered spaces are signs that actors are open to preference change, instead of just bargaining about their preferences derived from their discourses. Thus, it is logical to expect that transmission is higher if both discourse representation and signs of communicative action are present. However, this is not sufficient, since there might be cases where despite the two previous factors, certain actors are not able to engage and influence outcomes. In line with the insights of the transnational public sphere [

30] and meaningful participation [

51], the ability to influence decisions must also be assessed when evaluating transmission.

Looking at the case of the CFS, an assessment of the first factor is relatively straightforward. The CFS is widely regarded by its inclusivity, at least when compared to other global forums addressing food security. The observed high and diverse attendance of the plenary already suggests that this factor of transmission is relatively well achieved. Indeed, at the CFS, we find actors and positions that are clearly articulated with the discourse of autonomous and localized food systems, such as those actors that frame their interventions along the lines of the food sovereignty movement. We also find actors that can be clearly positioned at the other extreme, such as international financial institutions, actors from the private sector and delegates from countries with a strong neoliberal orientation.

Regarding the second factor, the clear majority of interviewees have strongly agreed with the statement that the atmosphere of the Committee is dominated by some sort of gentlemen’ code, which praises a high level of respect and truthfulness. This was affirmed even by organizations that defend opposite positions in several issues. Justification of positions is also pursued in many cases, said most of the interviewees, although not always. There were situations in which delegations were stuck in their reservations and did not attempt to justify these to the other participants, although this seems to be rather the exception than the rule.

The third factor is more challenging to assess. Brem-Wilson [

50] differentiates right to participate from substantive participation when analyzing the representation of peasant organizations at the CFS, thus focusing on the process. Another possibility is to consider one important CFS output and verify if it contains elements of the different discourses that characterize the public space, thus focusing on the outcomes. It is important to recognize the limitations of adopting just the second option, nevertheless. An exclusive focus on outcomes illuminates very little about the nuances of representation (who carries which discourse) and the actual degree of broad inclusivity. For example, the elite character, the professionalization and the technocratic communication found in intergovernmental negotiations such as the CFS can restrict the effective participation of grassroots constituencies that are to be the main beneficiaries and, thus, the legitimate carriers of food sovereignty discourses [

30,

57]. Thus, for more precisely evaluated transmission, the focus on assessing discourse success in influencing outcomes complements the other two factors of discourse representation and signs of ideal deliberative communication.

For these two aspects, we looked at the CFS policy recommendations on Connecting Smallholders to Markets [

59], considering that the production of this output was negotiated with energetic engagement by CFS actors [

30]. Regarding process, this engagement resulted in intense and high-quality policy debate, able to expand its initial restrictive and dominant framing of investing in smallholder agriculture that considered only the links to agro-industrial value chains. The process was opened after pressure and engagement of actors’ sharing views more associated with the autonomous and localized discourse and with the intervened through public policies discourse, leading to the organization of institutionalized forms of debate, such as the High-Level Forum on Connecting Smallholders to Markets [

59,

60]. A similar result is found when looking at the output. The policy recommendation contains a rather balanced view on the scale of food systems and on the role of states and markets in organizing these systems, an outcome that is particularly relevant considering that this is a topic where a liberal and market-oriented view tends to dominate, as in the case of discussions on this topic at the World Trade Organization (WTO), for example. It is important to highlight that this level of transmission was only achieved because participants identified the subject of smallholders and markets as one of high importance and consequently engaged and discussed extensively the issue within the CFS. This suggests engagement as one important condition for ensuring high levels of transmission, a point that could be further explored by analyzing other cases.

To summarize, transmission does seem to occur at rather unusual levels for a UN body, due to both the high diversity of representation, a regular mode of communication among CFS members and participants and the capacity of influencing debates. The achievement of relatively good levels of transmission is a positive achievement for the CFS in terms of its deliberative activity.

3.3. Accountability

Following Fuchs et al. [

61], we assessed accountability in terms of internal accountability (when representatives must give an account and be held responsible to their constituencies) and external accountability (when organizations should give an account to a broader range of affected stakeholders). Results were generated mostly through interviews, with questions focusing on formal and informal obligations towards their constituencies and between higher and lower hierarchical bodies.

Since the 2009 reform institutionalized the direct participation of publics affected by food insecurity within the Committee, external accountability can therefore be understood in two ways: (i) either as the CFS as a whole giving an account of their actions to external publics, for example when an external body is awarded the authority to evaluate the Committee’s performance, (ii) or as state actors giving an account of their actions to non-state actors represented in the CFS. The latter understanding of external accountability is in line with the vision brought by the 2009 reform, which adopted the right to food-based language [

58,

62] that strives for the accountability of duty-bearers (primarily national governments) towards rights-holders (citizens affected by food insecurity). In 2004, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) adopted the Voluntary Guidelines to support the progressive realization of the right to food in the context of national food security [

62]. In its vision approved in the 2009 Reform, the CFS adopts this instrument affirming that it “will strive for a world free from hunger where countries implement the voluntary guidelines for the progressive realization of the right to adequate food in the context of national food security” ([

58], p. 2).

Regarding internal accountability, the picture is mixed. Interviews have suggested that this type of accountability varies widely according to which organization is in question. Large representative democracies and many non-liberal democratic states have mechanisms for requiring delegates (mostly diplomats) to regularly report their activities to their capitals. Smaller states interviewed were revealed to not have those institutions, though in the end, this depends heavily on the capacities of the diplomatic corps, including the representative herself/himself. One can easily see that many small delegations have difficulties in following all the work streams of the Committee, which also implies difficulties in giving an account of their actions to constituencies.

A similar pattern was found when it comes to the civil society and private sector organizations. While the two mechanisms, CSM and PSM, facilitate accountability as formal and institutionalized groups, individually, only the larger and more resource-rich organizations were sufficiently organized to report back to their constituencies. It is still an open question whether what is reported effectively creates a real responsibility of the representative vis-à-vis the group that put her/him in the position. Some interviewees informed us that since the CFS is not a priority on their organizations’ agenda, it does not really create enough weight and responsibility for their representation.

External accountability is clearly a missing element of CFS deliberative capacity. Already by its status as a UN body that does not produce mandatory legislation of international character—such as conventions and treaties—CFS would by default have few reasons to be clearly held accountable by an external monitoring body. Since 2012, the CFS yearly reports to the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) preparing a document with “Main decisions and policy recommendations of the Committee on World Food Security”, which updates CFS activities and outputs. None of the interviewees have referred to this reporting as one of relevance to the building of CFS accountability. Furthermore, many interviews have suggested that this is also not a goal that members want to struggle with. On the other hand, many interviewees indicated that the fact that the CFS produces non-binding guidelines was as a strong point since this allows members and participants to interact in a freer and more open manner. A weak accountability is also found regarding state actors (duty-bearers) giving accounts of their actions to non-state actors represented in the CFS. Even though some state delegations organize periodical preparatory meetings with civil society and private sector actors from their nations, these are rarely institutionalized, and the practice is not the norm for most member-states. In other words, it is up to the discretion and interests of national governments to organize those consultations, which also opens up the possibility of instrumentalization.

Elements of external accountability can also be found in CFS’s 2017 Evaluation Report, which covers the 2009–2016 periods [

63]. Interviews identified (and the Evaluation Report confirmed) that there are different views on how far the Committee should engage in monitoring the application of its policy instruments at a national level. In general lines, civil society representatives tend to support a much stronger monitoring role for the CFS or, at least, stronger monitoring mechanisms conducted by national governments using CFS outputs, while national governments are those more reluctant to this. Even governments that were actively engaged in drafting key CFS policy instruments declared in interviews to be much less convinced of monitoring exercises that could create embarrassment and thus potentially fragilize their negotiation positions within the Committee.

The first monitoring exercise of the Committee took place recently at its 2016 Plenary, when members and participants discussed the application of the Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure (VGGTs), a major instrument produced by the CFS. Still, such periodical stocktaking exercises are seen by many—above all by civil society and international organizations’ representatives—as a profoundly weak accountability mechanism, with little significant impact on actions by participants. Its voluntary nature also offers little reason for expecting higher levels of accountability.

In sum, the CFS presents mixed results in terms of internal accountability and weak external accountability, which poses this as a factor to be better developed for those interested in increasing its deliberative capacity.

3.4. Meta-Deliberation

Arguably, the 2009 CFS Reform represents the first moments of meta-deliberation. Amid the world food crisis of 2007–2008, CFS members reformed its institutional structure and engagement rules, creating a much more relevant and dynamic committee. Reflexive capacity to understand how the food governance system is organized was necessary, and that made way for more structural changes to be approved by the Committee [

48]. When questioned whether this meta-deliberation capacity remains as high as before, interviewees indicated three factors eroding CFS’s meta-deliberative capacity.

The first factor was a lower political priority attached to food security issues driven by a substantial reduction of global food prices since the 2011 peaks. This important exogenous factor is used to drive member states to constantly reconsider the CFS role and operations. Even though food price volatility remains high, many interviewees—including those with Rome-based agency officers and current diplomatic representation of countries that were active in the reform process—have indicated that the political pressure derived from the global food crisis of 2009–2012 does not influence the work of the Committee as before. The “political urgency” of food security deviates the potential CFS members, and participants have to embark on a reflexive exercise on the institutional architecture of global food governance as a whole.

Second, we identify a growing misalignment among members and participants with respect to the directions the CFS should take in the long run. Reticence for supporting CFS activities is sustained by some actors, which also reflects the constant difficulties in securing funding for CFS operations. Delegations that played a very significant role in supporting and advancing the 2009 reform and an ambitious CFS agenda also show signs of misalignment. The EU, for example, which has been one of the leaders in post-reform initiatives, showed signs of internal struggle, while Latin America countries (another group that pioneered CFS reform) showed divided signs as to whether the Committee should address controversial issues or if it should try to put into practice what has already been agreed. Civil society continued to push for a stronger CFS, but is increasingly frustrated that some countries are unwilling to adopt a rights-based approach and instead redirect focus and time to re-negotiating rights-based language in every negotiation that is opened. This growing misalignment indicating an erosion of CFS’s reflexivity is related to the difficulties actors have in engaging in meta-debates, such as one that would discuss the diverging opinions on the direction of food systems and global food governance [

64].

Third, the issue of how to better represent farmers, a major constituency of any food debate, remains unresolved or, at least, sub-optimal according to all farmer groups interviewed. The authors conducted interviews with representatives of farmers groups participants in the Civil Society Mechanism (CSM), from both developed and developing countries, in the Private Sector Mechanism (PSM), from developing countries, as well as representatives from the World Farmers Organization (WFO) from developed countries. The issue was also raised by three government representatives and the Secretariat of the PSM that were interviewed. Farmers’ representation is complex, divided between different organizations, some aligning with the CSM and others following the PSM, and others as independent participants. Even within both mechanisms, farmer’s organizations revealed feeling uncomfortable in automatically aligning with these groups. The option of having some sort of independent farmers’ seat at the Bureau as a mechanism is a revolving and persistent item, also identified in the Evaluation Report. Proposed solutions have so far found very little support. Even though they are a relevant constituency in food governance, it is up for debate if the issue of farmers’ representation signifies an institutional concern requiring a Committee-wise solution rather than one based on the self-organization of farmer bodies themselves. It suggests, however, that possibilities for institutional reform in terms of representation rules are reduced in comparison with previous years and the 2009 Reform.

In sum, results lead us to believe that meta-deliberation at the CFS does exist, but it has been relatively eroded, thus inhibiting its larger deliberative capacity.

3.5. Decisiveness

Decisiveness is a key factor for assessing CFS’s deliberative capacity. Its status as an inter-governmental body producing voluntary instruments implies that CFS’s outcomes will only have consequences if actors have ownership and use them. The Committee identified this challenge and initiated monitoring processes to assess the implementation of its most relevant products. To more precisely analyze its decisiveness, we complemented interview results with findings from three processes conducted by the Committee to evaluate its own performance: (i) the CFS Effectiveness Survey of 2015 [

65]; (ii) a Global Thematic Event on the application of the VGGTs at its 2016 Plenary [

66]; and (iii) the 2017 Evaluation Report [

63]. One general remark made in most interviews is that CFS products are relatively new and that their potential consequences will require more time to unfold, implying that results discussed here should be taken as preliminary.

One of the nine criteria used by the CFS Effectiveness Survey of 2015 was CFS influence, defined as the “extent to which CFS is positively influencing policy processes and enhancement at regional and national levels through the delivery and promotion of its main outputs” ([

65], p. 7). When questioned about actual influence, 28–35% of respondents gave high ratings, 19–26% medium ratings and 26–34% low ratings on a five-point Likert-scale, depending on the CFS product in question. These results contrast with much higher values for potential helpfulness, with 59–65% high, 15–19% medium and 9–15% low ratings. This suggests that CFS products do have some influence, though not enough yet to fulfil the expectations that participants themselves associated with them.

Looking at a more specific case, the implementation of VGGTs that were widely discussed in a special event during the 43rd Session of the CFS, the Committee concluded that many awareness-raising and capacity-development activities are being organized to facilitate VGGT implementation. Interview results corroborate this finding, indicating that the VGGTs are being anchored in many regional frameworks and national development strategies, though it is difficult to assess the real impact of these legal reforms in land tenure dynamics at the local level. In fact, most constraints and challenges identified relate to reforming policy and legal framework, as well as operationalizing its implementation.

Consequentiality can be understood not only in terms of impact from policy instruments produced by CFS, but also if the CFS is fulfilling its expected roles assigned during its 2009 Reform process, a point examined at the 2017 Evaluation. On its 2009 reform, the CFS established six roles that would be sought in two phases: (i) coordination at global level (Phase 1); (ii) policy convergence (Phase 1); (iii) support and advice to countries (phase 1); (iv) coordination at national and regional levels (Phase 2); (v) promote accountability and share best practices at all levels (Phase 2) and develop a Global Strategic Framework for food security and nutrition (Phase 2) ([

58], pp. 2–3). The 2017 Evaluation assessed each of these six roles. As a general note, the report concluded that the Committee performs well on enhancing global coordination and that “[t]here is an uptake of main policy convergence products (VGGT), but it is too early as yet to assess the impact” ([

63], p. vii). Nevertheless, less positive performance was found in other roles such as the provision of support and advice to countries, coordination at national and regional levels and the promotion of accountability, which, in line with the previous sub-section, remains low at the level of sharing best practice.

The current analysis of CFS’s decisiveness has limitations considering that many of CFS’s instruments that could have consequences are relatively new and their usage and impacts are still unfolding. Still, interviews and CFS’s own reports suggest that the Committee has the potential to reach higher levels of decisiveness, in particular due to key instruments that receive more acknowledgements and recognition, such as the VGGTs.

In sum, results from the case study indicate that CFS includes a wide representation of food security discourses, institutionalized representations and facilitating mechanisms. This diversity of representation, aligned with deliberative modes of communication and influence, facilitates transmission, which seems to occur at unusually high levels for a UN body. Relatively strong levels of transmission are, therefore, a positive achievement of CFS in increasing deliberative capacity in food governance. This could be better developed if accountability were stronger, since we found mixed results of internal accountability and a weak external accountability mechanism. Furthermore, while meta-deliberation was found, so were signs of erosion in the reflexive capacity of the Committee. The analysis of decisiveness was limited due to the time spam of major CFS policy instruments. There are clear indications that CFS’s outcomes do have the potential to influence food dynamics at national and local levels, but the real impact of these instruments is still unfolding.

4. Conclusions

Multi-stakeholder participation has become a widespread feature of current approaches to global governance. The recently adopted 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development underlines this trend, stating that its follow-up processes should be “... open, inclusive, participatory and transparent for all people and will support reporting by all relevant stakeholders” [

67]. Given the prominence of this governance instrument, this paper explores the usefulness of a heuristic framework for better understanding the degree to which MSP contributes to making global governance more deliberative.

We therefore used the heuristic framework of Dryzek’s deliberation theory applied to the Committee on World Food Security (CFS), an intergovernmental body where participation of different stakeholders features prominently. The framework considers that deliberative systems are characterized by the core principles of authenticity, inclusiveness and consequentiality. It suggests that these principles can be operationalized by characterizing the deliberative system in question, its public and empowered spaces and the levels of transmission, accountability, meta-deliberation and decisiveness. This comprehensive approach complements recent academic efforts in better understanding the structures and patterns of global food and sustainability governance from a systemic point of view [

68].

In our assessment of the CFS case, we find achievements and limitations in the usefulness of this tool to analyze under which conditions the current MSP favors greater deliberation and more democratic decision making in global food governance. The framework clearly facilitates an overview analysis of the deliberative system, theoretically linking analytical elements that are generally treated separately in the literature, such as accountability and reflexive governance. Being built on a sound theoretical foundation rooted in the deliberation theory, the analysis goes beyond more comparative and empirical studies that only evaluate outcome performance. Indeed, it clearly links elements of MSP process (transmission) and outcomes (decisiveness), to comprehensively assess deliberation.

In terms of limitations, our assessment of CFS’s deliberative system would benefit from addressing power more explicitly, or more precisely how power influences each of one of the different elements of the deliberative system framework. Some elements for this analysis were suggested, e.g., identifying how power asymmetries shape criteria for selecting representatives, funding and rules of engagement. Thus, growing power asymmetries between participants can bring democratic decision-making into question, since this can hinder transmission of discourses, real accountability and the consequentiality of MSP decisions. In this regard, our content analysis of discourses was helpful in categorizing the different discourses that permeate the public and the empowered spaces, but it did not provide elements to precisely define the dominant discourses and those with more restricted access to decision-making. In this aspect, a full discourse analysis could bring more empirical evidence to how discourses are transmitting, also illuminating power dynamics.

There are also other avenues to investigate how power influences the different components of Dryzek’s framework. As mentioned when the framework was introduced, the concepts of instrumental, structural and discursive power [

46] can be used to assist the identification of flaws in transmission, accountability and reflexivity. Furthermore, Burnet and Duvall [

19] present a useful entry point for further conceptual development. Understanding power as social relations, their theoretical work shows that power can be compulsory or institutional in the form of structural circumstances and “through more diffuse constitutive relations to produce the situated social capacities of actors” ([

19], p. 48). In the assessment of the deliberative quality of MSP arrangements, this would mean taking note of the material, symbolic and normative resources that are part of relevant compulsory or institutional contexts and that play a role in the interaction of involved actors. Future research on MSP could point in these directions.

Finally, the case shows that MSP requires significant improvements to address deficits of accountability, meta-deliberation and decisiveness if such processes are to live up to the expectations associated with them. By proposing this analytical exercise, we expect to advance a heuristic framework useful for assessing deliberation in MSP that could be helpful in the context of the growing importance of this instrument in sustainable development and global governance.