From Collaborative to Hegemonic Water Resource Governance through Dualism and Jeong: Lessons Learned from the Daegu-Gumi Water Intake Source Conflict in Korea

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Considerations

2.1. Water Resource Governance

2.2. Collaborative Governance

“A governing arrangement where one or more public agencies directly engage non-state stakeholders in a collective decision-making process that is formal, consensus-oriented, and deliberative and that aims to make or implement public policy or manage public programs or assets”.[27]

“This definition stresses six important criteria: (1) The forum is initiated by public agencies or institutions, (2) participants in the forum include non-state actors, (3) participants engage directly in decision making and are not merely “consulted” by public agencies, (4) the forum is formally organized and meets collectively, (5) the forum aims to make decisions by consensus (even if consensus is not achieved in practice), and (6) the focus of collaboration is on public policy or public management”.[27]

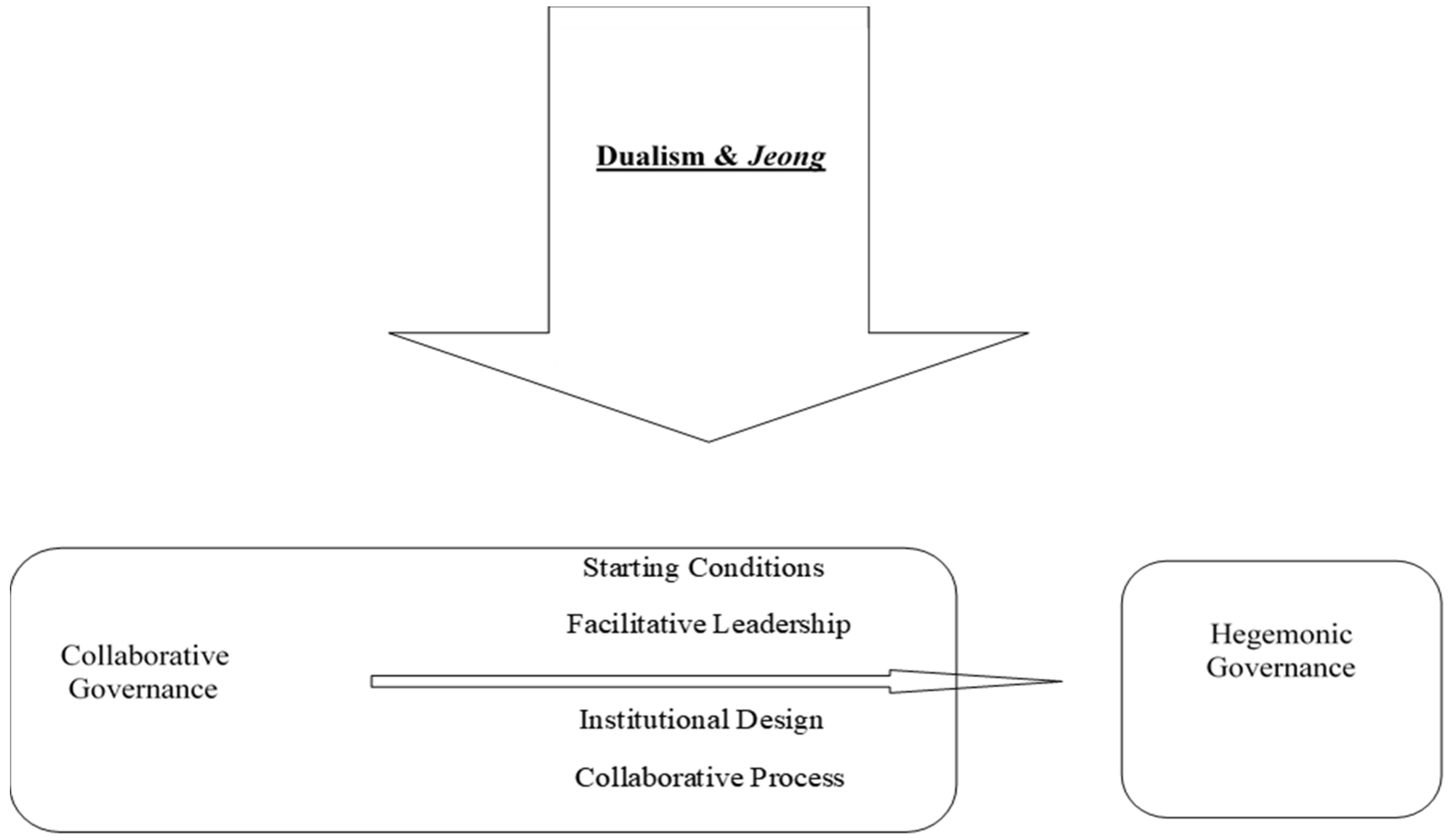

2.2.1. Limitations of Collaborative Governance: From Collaborative Governance to Hegemonic Governance

2.2.2. Hegemonic Governing Process

2.3. Dualism and Jeongish Citizenship in Korean Society

2.4. Research Design

2.5. Conflict on the Relocation of the Water Intake Plant: Water Resource Governance in Daegu–Gumi Water Intake Source Conflict

3. Application of the Theory to the Case Study

3.1. From Collaborative Governance to Hegemonic Governance because of Dualism and Jeongish Citizenship

3.1.1. Starting Conditions

3.1.2. Facilitative Leadership

3.1.3. Institutional Design

3.1.4. Collaborative Process

4. Conclusions

4.1. Contributions

4.2. Lessons Learned

4.3. Implications for Sustainability

4.4. Further Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reig, P.; Maddocks, A.; Gassert, F. World’s 36 Most Water-Stressed Countries. World Resources Institute. 12 December 2013. Available online: http://www.wri.org/blog/2013/12/world%E2%80%99s-36-most-water-stressed-countries (accessed on 1 September 2016).

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport (MOLIT) & K-Water. Water and Future; MOLIT & K-Water: South Korea, 2016.

- Kim, J.Y.; Kwak, M.S. A Study on the Governance System in the Process of Foreign Advance of Water Resource Management; Korean Association of Governmental Studies (KAGOS): South Korea, 2015; Volume 3, pp. 38–60. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, J.H. Water Shortage Grips Korean Peninsula. Korea Herald. 30 March 2010. Available online: http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20090323000074 (accessed on 1 September 2016).

- Kwon, K.D.; Yim, J.B.; Chang, W.Y. The Analysis of Intergovernmental Conflict Structure on the Use Water Resource. Korean Soc. Public Adm. 2004, 15, 551–580. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco, I. Analysing Urban Governance Networks: Bringing Regime Theory Back In. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2013, 31, 276–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Beyond Markets and States: Polycentric Governance of Complex Economic Systems. Am. Econ. Rev. 2009, 100, 641–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.D. Collaborative Governance and Development of the Yeongnam Region: A Conceptual Reconsideration. J. Korean Assoc. Reg. Geogr. 2015, 21, 427–449. [Google Scholar]

- Swyngedouw, E. Governance Innovation and the Citizen: The Janus Face of Governance-Beyond-the-State. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 1991–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akamani, K. Adaptive water governance: Integrating the human dimensions into water resource governance. J. Contemp. Water Res. Educ. 2016, 158, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lathem, K.W. The World Water Conferences at Mar del Plata. Can. Water Resour. J. 1977, 2, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirumachi, N.; Van Wyk, E. Cooperation at different scales: Challenges for local and international water resource governance in South Africa. Geogr. J. 2010, 176, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J. Assuming too much? Participatory water resource governance in South Africa. Geogr. J. 2011, 177, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzungu, E. Water for All: Improving Water Resource Governance in Southern Africa; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- K’akumu, O.A. Mainstreaming the participatory approach in water resource governance: The 2002 water law in Kenya. Development 2008, 51, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolavalli, S.; Kerr, J. Scaling up participatory watershed development in India. Dev. Chang. 2002, 33, 213–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennox, J.; Proctor, W.; Russell, S. Structuring stakeholder participation in New Zealand’s water resource governance. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 1381–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R.A.W. The New Governance: Governing without Government. Political Stud. 1996, XLIV, 652–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R.A.W. Understanding Governance: Ten Years On. Organ. Stud. 2007, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. An Assessment of the Institutional Analysis and Development Framework. In Theories of the Policy Process; Sabatier, P., Ed.; University of California: Davis, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Y.D. Public Administration in a Current Nation; Bubmoonsa: Seoul, Korea, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, K.W.; Brower, R.; Ahmad, M.S. Factors that Influence County Government Expenditures and Revenues: A Study of Florida County Governments. Lex Localis 2018, 16, 47–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Fording, R. Second-Order Devolution and Implementation of TANF in the U.S. States. State Politics Policy Q. 2010, 10, 341–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, J.M.; Tullock, G. The Calculus of Consent. Logical Foundations of Constitutional Democracy; University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Gamper, C.D.; Turcanu, C. Can public participation help managing risks from natural hazards? Saf. Sci. 2009, 47, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, J.B.; Cho, S.J.; Kim, P.D.; Park, H.Y.; Ha, D.H. Strategies to Reinforce Collaborative Governance of Local Government; Korea Research Institute for Local Administration: Seoul, Korea, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.S. Collaborative governance and publicness. Mod. Soc. Public Adm. 2010, 20, 23–53. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, H.; Skelcher, C. Working across Boundaries: Collaboration in Public Services; Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, J.S. Challenging Governance Theory: From Networks to Hegemony; Policy Press University of Bristol: Bristol, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, B.D.; Chae, E.H.; Yang, M.J. Daegu metropolitan government’s plan of relocation of water intake plant and collaborative governance between regions. J. Korean Assoc. Reg. Geogr. 2016, 22, 64–85. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. On Korean Dual Civil Society: Thinking through Tocqueville and Confucius. Contemp. Political Theory 2010, 9, 434–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidet, E. Explaining the Third Sector in South Korea. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2002, 13, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, T.K. Government Policy Attitude on Nonprofit Organizations and Activities: A Comparative Study between Japan and Korea. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Third Sector in Asia, Bangkok, Thailand, 20–22 November 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Deuchler, M. The Confucian Transformation of Korea: A Study of Society and Ideology; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, B. Confucianism in Contemporary Korea. In Confucian Traditions in East Asian Modernity: Moral Education and Economic Culture in Japan and the Four Mini-Dragons; Tu, W., Ed.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Baek, D.I.; Choi, B.K.; Lee, K.I.; Kim, S.H.; Shim, G.S.; Kim, I.Y.; Woo, Y.S.; Lee, J.G.; Shin, M.J.; Yoo, E.J. No More Neighborhood. Muddy Fight among Local Autonomous Governments on the Water Resource and Name of Bridge. 2016. Available online: http://www.yonhapnews.co.kr/bulletin/2016/07/01/0200000000AKR20160701167800055.HTML?input=1195m (accessed on 15 October 2016).

- Kim, H.T. [Contribution] Resolution for the Movement Daegu Water Intake Stations. Yeongnam Ilbo. 3 April 2014. Available online: http://www.yeongnam.com/mnews/newsview.do?mode=newsView&newskey=20140403.010250802030001 (accessed on 15 October 2016).

- Choi, S.H. Daegu-Gumi City will create a Daegu water intake source moving commission. Yonhap News. 17 February 2015. Available online: http://www.yonhapnews.co.kr/bulletin/2015/02/17/0200000000AKR20150217101551053.HTML (accessed on 22 October 2016).

- “We want clean water, too”: Moving Daegu Water Intake Sources Has Been in Conflict for Six Years. Yonhap News. 7 September 2015. Available online: http://www.yonhapnews.co.kr/bulletin/2015/09/03/0200000000AKR20150903193700053.HTML (accessed on 15 October 2016).

- Yoon, J.H.; Kim, B.J. [The Worst Draught, Water War] Neighborhoods in Youngnam Area is Worse than Strangers: Total Wars among Autonomous Entities. Herald Corporation. 21 February 2016. Available online: http://biz.heraldcorp.com/common_prog/newsprint.php?ud=20160221000102 (accessed on 23 October 2016).

- Kang, T.A. Drifting Un-Mun Dam’s Water Supply Water to Ulsan is Unavoidable. Ulsan Maeil. 24 February 2016. Available online: http://www.iusm.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=645462 (accessed on 23 October 2016).

- Daegu Water Intake Source Problems will be Discussed after General Election. Yeongnam Ilbo. 2 March 2016. Available online: http://www.yeongnam.com/mnews/newsview.do?mode=newsView&newskey=20160302.010150748210001 (accessed on 23 October 2016).

- Son, S.W. The Eighth Discussion of the Water Intake Source Moving was Unsuccessful. Yeongnam Ilbo. 2 June 2016. Available online: http://www.yeongnam.com/mnews/newsview.do?mode=newsView&newskey=20160602.010080736440001 (accessed on 23 October 2016).

- Kim, D.H. Daegu Water Intake Source Moving: Ninth Daegu-Gumi Citizens and Bureaucrats Commission Held. Youtong News. 18 November 2016. Available online: http://www.youtongnews.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=01_3&wr_id=1368 (accessed on 21 October 2018).

- Self-alternative Method is Necessary When Failing to Compromise: Daegu Water Intake Sources Moving with Gumi. Yonhap News. 28 August 2015. Available online: http://www.yonhapnews.co.kr/bulletin/2015/08/28/0200000000AKR20150828134400053.HTML (accessed on 23 October 2016).

- Kim, Y.T. Creating Special Committee for Daegu Water Intake Sources Moving. KyeongBuk Maeil. 20 October 2016. Available online: http://www.kbmaeil.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=396912 (accessed on 23 October 2016).

- Futrell, R. Technical Adversarialism and Participatory Collaboration in the US Chemical Weapons Disposal Program. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2003, 28, 451–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunton, T.I.; Day, J.C. The Theory and Practice of Collaborative Planning in Resource and Environmental Management. Environments 2003, 31, 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Imperial, M.T. Using Collaboration as a Governance Strategy: Lessons from Six Watershed Management Programs. Adm. Soc. 2005, 37, 281–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasbergen, P.; Driessen, P.P. Interactive Planning of Infrastructure: The Changing Role of Dutch Project Management. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2005, 23, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, J.A.; Comfort, M.E.; Weiner, B.J. Governance in Public-Private Community Health Partnerships: A Survey of the Community Care Network: SM Demonstration Sites. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 1998, 8, 311–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beierle, T.C.; Konisky, D.M. What Are We Gaining From Stakeholder Involvement? Observations from Environmental Planning in the Great Lakes. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2001, 19, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkerhoff, D.W. Exploring State—Civil Society Collaboration: Policy Partnerships in Developing Countries. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 1999, 28, 59–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdock, B.S.; Wiessner, C.; Sexton, K. Stakeholder Participation in Voluntary Environmental Agreements: Analysis of 10 Project XL Case Studies. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2005, 30, 223–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, C.; Winter, M. The Problem of Common Land: Towards Stakeholder Governance. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 1999, 42, 613–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tett, L.; Crowther, J.; O’Hara, P. Collaborative Partnerships in Community Education. J. Educ. Policy 2003, 18, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangen, S.; Huxham, C. Nurturing Collaborative Relations: Building Trust in Interorganizational Collaboration. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2003, 39, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentrup, G. Evaluation of a Collaborative Model: A Case Study Analysis of Watershed Planning in the Intermountain West. Environ. Manag. 2001, 27, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, P. Is There Space for Organisation from Below Within the UK Government’s Action Zones? A test of ‘Collaborative Planning. Urban Stud. 2000, 37, 1261–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl-Wostl, C.; Hare, M. Processes of Social Learning in Integrated Resources Management. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 14, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrislip, D.D.; Larson, C.E. Collaborative Leadership: How Citizens and Civic Leaders Can Make a Difference; Jossey-Bass Inc. Pub.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1994; Volume 24. [Google Scholar]

- Roussos, S.T.; Fawcett, S.B. A Review of Collaborative Partnerships as a Strategy for Improving Community Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2000, 21, 369–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warner, J.F. More sustainable participation? Multi-stakeholder platforms for integrated catchment management. Water Resour. Dev. 2006, 22, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weech-Maldonado, R.; Merrill, S.B. Building Partnership with the Community: Lessons from the Camden Health Improvement Learning Collaborative. J. Healthc. Manag. 2000, 45, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, T.; Howard-Pitney, B.; Feighery, E.C.; Altman, D.G.; Endres, J.M.; Roeseler, A.G. Characteristics and Participant Perceptions of Tobacco Control Coalitions in California. Health Educ. Res. 1993, 8, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.W.; Yi, S.H.; Choi, S.O. Does Blake and Mouton’s Managerial Grid Work? Int. Rev. Public Adm. 23, 103–118. [CrossRef]

- Huxham, C. Theorizing collaboration practice. Public Manag. Rev. 2003, 5, 401–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringham, E.P. Kaldor-Hicks efficiency and the problem of central planning. Q. J. Austrian Econ. 2001, 4, 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.E.; Chai, W.H.; Choi, J.H.; Kim, S.K. A Study of Cooperations among Local Governments. J. Local Gov. Stud. 2009, 21, 97–119. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, S.M. Conflict Management and Collaborative Governance in the Intergovernmental Relationship. J. Northeast. Asian Stud. 2006, 11, 101–120. [Google Scholar]

- Nelles, J. Cooperation and Capacity? Exploring the Sources and Limits of City-Region Governance Partnerships. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2013, 37, 1349–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.W. Political and Policy Responses to the Sewol Ferry Disaster: Examining Change through Multiple Theory Lenses. Ph.D. Thesis, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL, USA, 2017, unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative platforms as a governance strategy. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2017, 28, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Date | Content |

|---|---|

| 17 March 2015 | - Agreement on the venue, the election of a chief of the commission, and other operations [31]. |

| 9 April 2015 | - Review Report of the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport (MOLIT) is verified [31]. - Compromise reached for the City of Daegu to examine the conflicting sections [31]. |

| 23 May 2015 | - The decision to visit and refer to other domestic conflicting areas in South Korea [31]. |

| 22 July 2015 | - Debate on the validity of the MOLIT Review Report [31]. ➔ The City of Gumi distrusts the MOLIT Review Report [31]. |

| 3 September 2015 | - Debate on the validity of the MOLIT Review Report [31]. ➔ Presentation of the Review Report by the author from the Korea Institute of Civil Engineering and Building Technology [31]. |

| 14 January 2016 [41] | - While the members from Daegu suggested that water pollution problems must be the decision of the Ministry of the Environment, the members from Gumi delayed their response [41] and had the following questions: How would the plan deal with water problems in the case of water quality accidents?; how does the plan manage water from other dams? (Yeongcheon Dam); how does the plan develop the whole of the Nakdong River? [42]. From these questions, it was clear that Gumi’s position was almost the same as a rejection [41]. |

| 29 March 2016 [43] | - The City of Daegu suggested the two cities make a joint submission to the MOLIT to request a verification of whether relocating the Daegu water intake sources would cause a reduction in the quantity and quality of water around the Gumi area [44]. |

| 1 June 2016 | - The decision of the seventh meeting was delayed [44]. |

| 16 November 2016 | - Joint suggestion to verify the quality of water of Nakdong River [45] |

| - No follow-up meeting was reported until 21 October 2018. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cho, K.W.; Jung, K. From Collaborative to Hegemonic Water Resource Governance through Dualism and Jeong: Lessons Learned from the Daegu-Gumi Water Intake Source Conflict in Korea. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4405. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124405

Cho KW, Jung K. From Collaborative to Hegemonic Water Resource Governance through Dualism and Jeong: Lessons Learned from the Daegu-Gumi Water Intake Source Conflict in Korea. Sustainability. 2018; 10(12):4405. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124405

Chicago/Turabian StyleCho, Ki Woong, and Kyujin Jung. 2018. "From Collaborative to Hegemonic Water Resource Governance through Dualism and Jeong: Lessons Learned from the Daegu-Gumi Water Intake Source Conflict in Korea" Sustainability 10, no. 12: 4405. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124405

APA StyleCho, K. W., & Jung, K. (2018). From Collaborative to Hegemonic Water Resource Governance through Dualism and Jeong: Lessons Learned from the Daegu-Gumi Water Intake Source Conflict in Korea. Sustainability, 10(12), 4405. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124405