Integrating Voluntary Sustainability Standards in Trade Policy: The Case of the European Union’s GSP Scheme

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Addressing the Compliance Gap in the EU’s Current Generalised Scheme of Preferences by Integrating VSS

2.1. EU’s Current Generalised Scheme of Preferences

2.2. The Compliance Gap

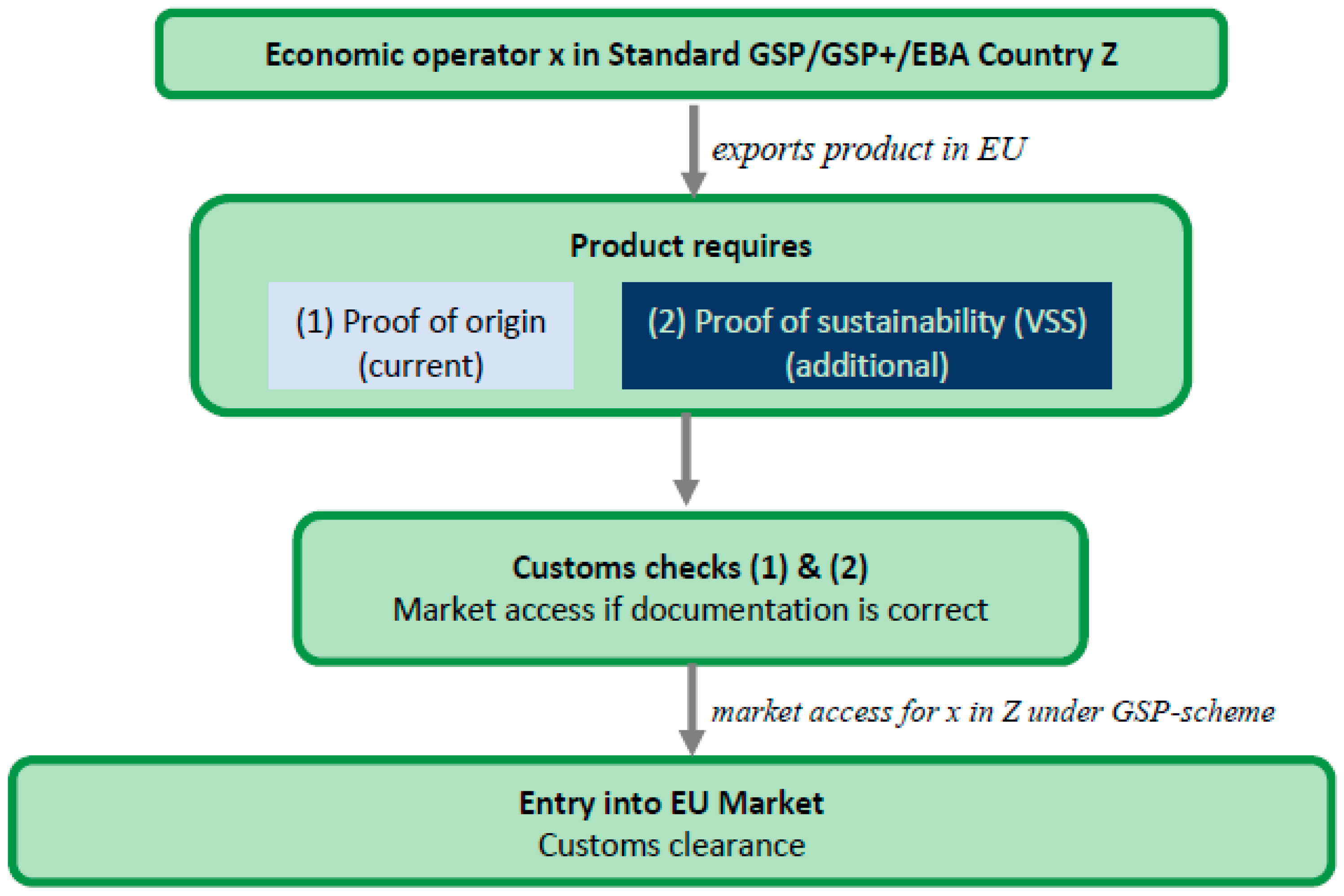

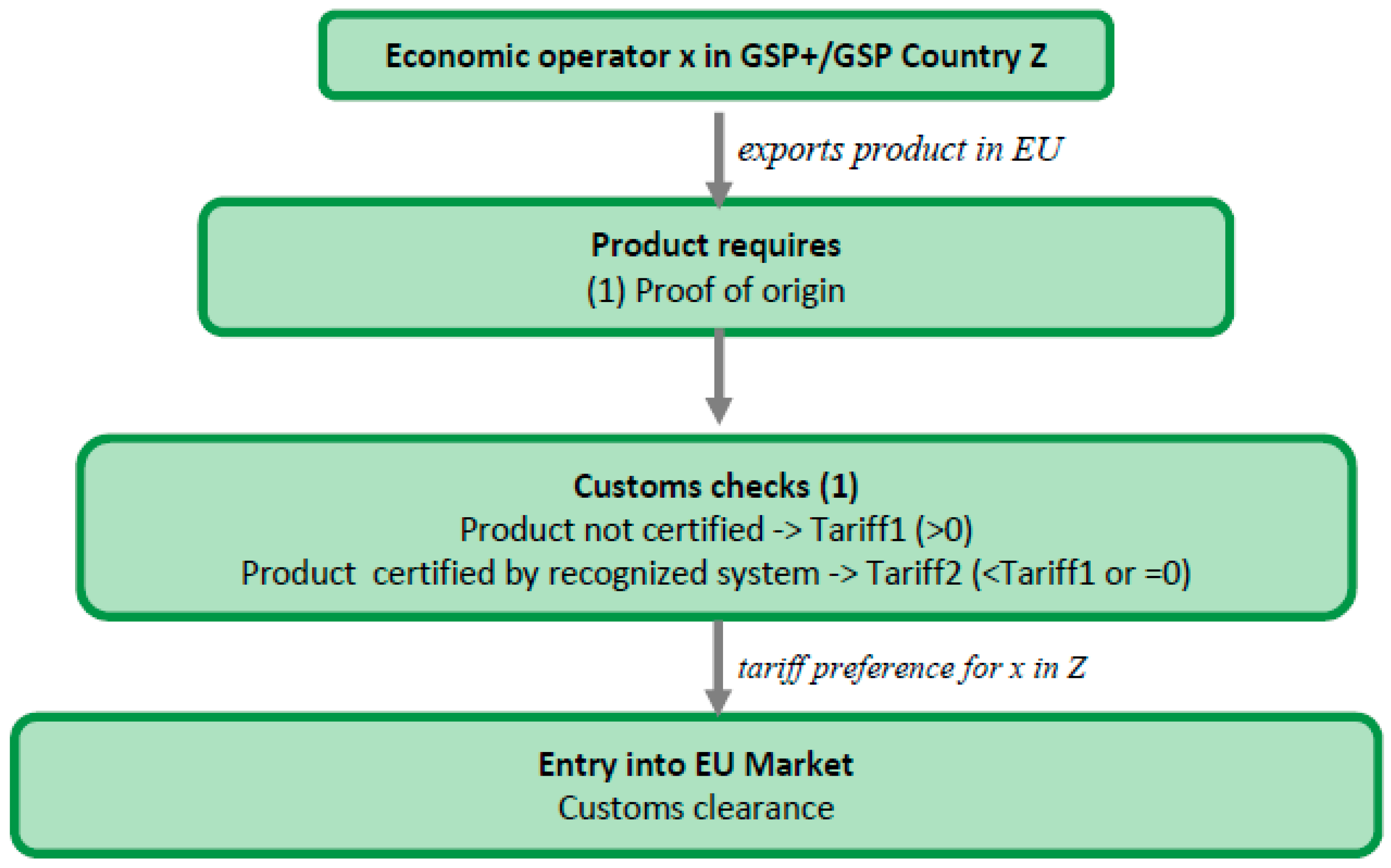

2.3. Two Models to Integrate VSS in GSP

3. Assessment of the Integration of VSS in the GSP Scheme

3.1. Overlap in Substantive Provisions

3.2. Impact on GSP

3.2.1. Impact on the State-to-State Nature of the GSP Scheme

3.2.2. Dynamic Nature of the GSP Scheme

3.2.3. Limitations on the Possibilities for Further Tariff Differentiation

3.2.4. Effects on the Utilisation Rate of GSP Tariffs

3.3. VSS as an Appropriate Tool

3.3.1. Effectiveness of VSS

3.3.2. Governance of VSS

3.3.3. Capacity of VSS

3.3.4. Availability of VSS and Applicability to Export Sectors

3.4. Cost Issues Related to VSS Certification

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marx, A.; Ebert, F.; Hachez, N.; Wouters, J. Dispute Settlement in the Trade and Sustainable Development Chapters of EU Trade Agreements: Report for the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 2017. Available online: https://ghum.kuleuven.be/ggs/publications/books/final-report-9-february-def.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2018).

- Marx, A.; Wouters, J.; Natens, B.; Geraets, D. Non-traditional Global Governance: The Case of Governing Through Trade. In Global Governance through Trade; Wouters, J., Marx, A., Geraets, D., Natens, B., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- REGULATION (EU) No 978/2012 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 25 October 2012 Applying a Scheme of Generalised Tariff Preferences and Repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 732/2008 (GSP Regulation). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32012R0978&from=EN (accessed on 21 November 2018).

- European Commission. Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on the Generalised Scheme of Preferences covering the period 2014–2015; COM (2016) 29 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2016; p. 3.

- Marx, A.; Brando, N.; Lein, B. Strengthening Labour Rights Provisions in Bilateral Trade Agreements. The case of voluntary sustainability standards. Glob. Policy 2017, 8, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schukat, P.; Rust, J. Tariff preferences for sustainable products. In An Examination of the Potential Role of Sustainability Standards in the Generalized Preference Systems Based on the European Union Model (GSP); Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH: Bonn, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schukat, P.; Rust, J.; Baumhauer, J. Tariff Preferences for Sustainable Products: A Summary. In Voluntary Standard Systems, Natural Resource Management in Transition; Schmitz-Hoffmann, C., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 419–430. [Google Scholar]

- Fiorini, M.; Solleder, O.; Hoekman, B.; Taimasova, R.; Jansen, M.; Wozniak, J.; Schleifer, P. Exploring Voluntary Sustainability Standards Using ITC Standards Map: On the Accessibility of Voluntary Sustainability Standards for Suppliers; ITC-Working Paper 04-2016; ITC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lambin, E.F.; Meyfroidt, P.; Rueda, X.; Blackman, A.; Börner, J.; Cerutti, P.O.; Dietsch, T.; Jungmann, L.; Lamarque, P.; Lister, J.; et al. Effectiveness and Synergies of Policy Instruments for Land Use Governance in Tropical Regions. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 28, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambin, E.; Thorlakson, T. Sustainability Standards: Interactions between private actors, civil society and governments. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2018, 43, 369–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberlein, B.; Abbott, K.; Black, J.; Meidinger, E.; Wood, S. Transnational Business Governance Interactions: conceptualization and framework for analysis. Regul. Gov. 2014, 8, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auld, G. Confronting trade-offs and interactive effects in the choice of policy focus: Specialized versus comprehensive private governance. Regul. Gov. 2014, 8, 126–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grime, M.; Wright, G. Delphi Method; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament Research Service. Human Rights in EU Trade Policy: Unilateral Measures; European Parliament Research Service: Brussels, Belgium, 2017; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission and European External Action Service. The EU Special Incentive Arrangement for Sustainable Development and Good Governance (‘GSP+’) Covering the Period 2014–2015, Joint Staff Working Document; SWD (2016) 8 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Mid-Term Evaluation of the EU’s Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. Available online: http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2017/september/tradoc_156085.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2018).

- Richardson, B.; Harrison, J.; Campling, L. Labour Rights in Export Processing Zones with a Focus on GSP+ Beneficiary Countries; European Parliament: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pakistani Workers Confederation. GSP Plus and Labor Standards in Pakistan: The Chasm between Conditions and Compliance; FES: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, B.A. Mobilizing for Human Rights: International Law in Domestic Politics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mosley, L. Labor Rights and Multinational Production; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hafner-Burton, E.M. Making Human Rights a Reality; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, A.; Soares, J. Does Integrating Labour Provisions in Free Trade Agreements Make a Difference? An exploratory analysis of freedom of association and collective bargaining rights in 13 EU Trade Partners. In Global Governance through Trade; Wouters, J., Marx, A., Geraets, D., Natens, B., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, A.; Soares, J.; van Acker, W. The protection of the rights of freedom of association and collective bargaining. A longitudinal analysis over 30 years in 73 countries. In Global Governance of Labour Rights; Marx, A., Wouters, J., Beke, L., Rayp, G., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- UNFSS. Voluntary Sustainability Standards. Today’s Landscape of Issues and Initiatives to Achieve Public Policy Objectives; United Nations Forum on Sustainability Standards: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Van Oorschot, M.; Kok, M.; Brons, J.; van der Esch, S.; Janse, J.; Rood, T.; Vixseboxse, E.; Wilting, H.; Vermeulen, W. Sustainability of International Dutch Supply Chains. Progress, Effects and Perspectives; PBL: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2014; Available online: www.pbl.nl/en (accessed on 15 October 2018).

- Marx, A.; Wouters, J. Competition and Cooperation in the Market of Voluntary Standards. In International standardization—Law, Economics and Politics; Delimatsis, P., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Potts, J.; Lynch, M.; Wilkings, A.; Huppé, G.; Cunningham, M.; Voora, V. The State of Sustainability Initiatives Review: Standards and the Green Economy; Joint Initiative of ENTWINED, IDH, IIED, FAST, IISD; State of Sustainability Initiatives: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ponte, S.; Daugbjerg, C. Biofuel Sustainability and the Formation of Transnational Hybrid Governance. Environ. Politics 2015, 24, 96–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleifer, P. Orchestrating sustainability: The case of European Union biofuel governance. Regul. Gov. 2013, 7, 533–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overdevest, C.; Zeitlin, J. Assembling an experimentalist regime: Transnational governance interactions in the forest sector. Regul. Gov. 2014, 8, 22–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meliado, F. Private Standards, Trade, and Sustainable Development: Policy Options for Collective Action; International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development (ICTSD): Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ugarte, S.; Van Dam, J.; Spijkers, S.; Gaebler, M. Recognition of Private Certification Schemes for Public Regulation. Lessons Learned from the Renewable Energy Directive; Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ): Bonn, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, B. The New Regulators? Assessing the Landscape of Multi-Stakeholder Initiatives; MSI Integrity and Kenan Institute for Ethics, Duke University: Durham, NC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Portela, C. Enforcing Respect for Labour Standards with Targeted Sanctions; Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung: Singapore, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Keck, A.; Lendle, A. New evidence on preference utilization. In Economic Research and Statistics Division; Staff Working Paper ERSD-2012–12; World Trade Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012; p. 6. Available online: https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/reser_e/ersd201212_e.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2018).

- FAO. Impact of International Voluntary Standards on Smallholder Market Participation in Developing Countries: A Review of Literature; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- International Trade Centre. The Impacts of Private Standards on Global Value Chains. In Literature Review Series on the Impacts of Private Standards Part I; International Trade Centre (ITC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Anner, M. Corporate Social Responsibility and Freedom of Association Rights the Precarious Quest for Legitimacy and Control in Global Supply Chains. Politics Soc. 2012, 40, 609–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egels-Zanden, N.; Lindholm, H. Do codes of conduct improve worker rights in supply chains? A study of Fair Wear Foundation. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 107, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fransen, L. Corporate Social Responsibility and Global Labor Standards: Firms and Activists in the Making of Private Regulation; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- LeBaron, G.; Lister, J.; Dauvergne, P. Governing Global Supply Chain Sustainability through the Ethical Audit Regime. Globalizations 2017, 14, 958–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, R. The Promise and Limits of Private Power. Promoting Labor Standards in a Global Economy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, A.; Wouters, J. Intermediaries in Global Labour Governance. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2017, 607, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, A. Legitimacy, Institutional Design and Dispute Settlement: The Case of Eco-certification systems. Globalizations 2014, 11, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, A. Varieties of Legitimacy: A Configurational Institutional Design Analysis of Eco-labels. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2013, 26, 268–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, E.A. Who Governs Socially-Oriented Standards? Not the Producers of Certified Products. World Dev. 2017, 91, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISEAL Alliance. Chain of Custody: Models and Definitions; ISEAL Alliance: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lund-Thomsen, P.; Nadvi, K. Clusters, Chains and Compliance: Corporate Social Responsibility and Governance in Football Manufacturing in South Asia. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 93, 201–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fair Wear Foundation (FWF). Fear Wear Foundation Annual Report; FWF: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fair Wear Foundation (FWF). Audit Manual; FWF: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Fair Wear Foundation (FWF). Brand Performance Check Guide for Affiliates; FWF: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Loconto, A. Models of assurance: Diversity and standardization of modes of intermediation. Ann. Am. Acad. 2017, 670, 112–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UTZ’ RESPONSE. To the report: ‘External Evaluation of the UTZ tea program in Sri Lanka’. By Nucleus Foundation and Fair & Sustainable Advisory Services. Available online: https://www.utz.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/UTZ-Response-External-evaluation-on-the-UTZ-tea-program-in-Sri-Lanka.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2018).

- Hidayat, N.; Offermans, A.; Glasbergen, P. On the Profitability of Sustainability Certification: An Analysis among Indonesian Palm Oil Smallholders. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 7, 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, A.; Wouters, J. Is Everybody on Board? Voluntary Sustainability Standards and Green Restructuring. Development 2015, 58, 511–520. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057/s41301-016-0051-z (accessed on 23 November 2018). [CrossRef]

- Marx, A.; Cuypers, D. Forest Certification as a Global Environmental Governance Tool: What is the Macro-impact of the Forest Stewardship Council. Regul. Gov. 2010, 4, 304–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayleur, C.; Balmford, A.; Buchanan, G.M.; Butchart, S.H.; Walker, C.C.; Ducharme, H.; Green, R.E.; Milder, J.C.; Sanderson, F.J.; Thomas, D.H. Where are commodity crops certified, and what does it mean for conservation and poverty alleviation? Biol. Conserv. 2018, 217, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, S.; Von Hagen, O. Linking Local Experiments to Global Standards: How Project Networks Promote Global Institution-building. Scand. J. Manag. 2010, 26, 398–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amengual, M.; Fine, J. Co-enforcing Labour Standards: the unique contributions of state and worker organizations in Argentina and United States. Regul. Gov. 2016, 11, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toffel MShort, J.; Ouellet, M. Codes in context: How states, markets, and civil society shape adherence to global labor standards. Regul. Gov. 2015, 9, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament Committee on the Environment, Public Health and Food Safety. Report on Palm Oil and Deforestation of Rainforests; European Parliament: Brussels, Belgium, 2017.

| Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (1948) | |

| International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (1965) | |

| International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966) | Fairtrade Textile Standard |

| International Covenant on Economic Social and Cultural Rights (1966) | |

| Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (1979) | |

| Convention Against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (1984) | Fairtrade Textile Standard |

| Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) | FT Gold Standard, FT International-Small Producers Organizations, FT Textile Standard, Goodweave |

| Convention concerning Forced or Compulsory Labour, No 29 (1930) | ASC-Salmon-Shrimp-Pangasius, FT Standard for Hired Labour–Gold Standard-Small Producers Organizations, FT Trader, FT Textile Standard, FSC-CoC/FM, Goodweave, MSC, Responsible Jewelry Council, Roundtable on Sustainable Biomaterials, RA, Union for Ethical Biotrade |

| Convention concerning Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise, No 87 (1948) | ASC-Salmon-Shrimp-Pangasius, BCI, Bonsucro, FT Standard for Hired Labour, FT Gold Standard, FT-Small Producers Organizations, FT Trader, FT Textile Standard, FSC CoC/FM, Goodweave, Responsible Jewelry Council, Roundtable on Sustainable Biomaterials, RA, Union for Ethical Biotrade, UTZ, 4C-GCP |

| Convention concerning the Application of the Principles of the Right to Organise and to Bargain Collectively, No 98 (1949) | ASC-Salmon-Shrimp-Pangasius, BCI, Bonsucro, FT Standard for Hired Labour, FT-Gold Standard, FT Small Producers Organizations, FT Trader, FT Textile Standard, FSC CoC/FM, Goodweave, Responsible Jewelry Council, Roundtable on Sustainable Biomaterials, RA, Union for Ethical Biotrade, UTZ, 4C-GCP |

| Convention concerning Equal Remuneration of Men and Women Workers for Work of Equal Value, No 100 (1951) | BCI, Bonsucro, FT Standard for Hired Labour, FT-Gold Standard, FT-Small Producers Organizations, FT Trader, FT Textile Standard, FSC CoC/FM, Goodweave, Responsible Jewelry Council, Roundtable on Sustainable Biomaterials, RA, Union for Ethical Biotrade, UTZ, 4C-GCP |

| Convention concerning the Abolition of Forced Labour, No 105 (1957) | BCI, Bonsucro, FT Standard for Hired Labour, FT-Gold Standard, FT Small Producers Organizations, FT Trader, FT Textile Standard, FSC CoC/FM, Goodweave, Responsible Jewelry Council, Roundtable on Sustainable Biomaterials, RA, Union for Ethical Biotrade, UTZ, 4C-GCP |

| Convention concerning Discrimination in Respect of Employment and Occupation, No 111 (1958) | ASC-Salmon-Shrimp-Pangasius, BCI, Bonsucro, FTStandard for Hired Labour, FT Gold Standard, FT Small Producers Organizations, FT Trader, FT Textile Standard, FSC-CoC/FM, Goodweave, Responsible Jewelry Council, Roundtable on Sustainable Biomaterials, RA, Union for Ethical Biotrade, UTZ, 4C-GCP |

| Convention concerning Minimum Age for Admission to Employment, No 138 (1973) | ASC-Salmon-Shrimp-Pagasius, BCI, Bonsucro, FT Standard for Hired Labour, FT Gold Standard, FT Small Producers Organizations, FT Trader, FT Textile Standard, FSC CoC/FM, Goodweave, Marine Stewardship Council, Responsible Jewelry Council, Roundtable on Sustainable Biomaterials, RA, Union for Ethical Biotrade, UTZ, 4C-GCP |

| Convention concerning the Prohibition and Immediate Action for the Elimination of the Worst Forms of Child Labour, No 182 (1999) | ASC-Salmon-Shrimp-Pangasius, BCI, Bonsucro, FT Standard for Hired Labour, FT Gold Standard, FT Small Producers Organizations, FT Trader, FT Textile Standard, FSC CoC/FM, Goodweave, Responsible Jewelry Council, Roundtable on Sustainable Biomaterials, RA, Union for Ethical Biotrade, UTZ, 4C-GCP |

| Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (1973) | ASC-Salmon-Pangasius, FSC CoC/FM, RA, Union for Ethical Biotrade, UTZ |

| Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer (1987) | Bonsucro, 4C-GCP |

| Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal (1989) | Responsible Jewelry Council |

| Convention on Biological Diversity (1992) | FT Standard for Hired Labour, FT Gold Standard, FT Small Producers Organizations, FT Trader, Fairtrade Textile Standard, FSC CoC/FM, MSC, Roundtable on Sustainable Biomaterials, RA, Union for Ethical Biotrade |

| The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (1992) | |

| Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety (2000) | |

| Stockholm Convention on persistent Organic Pollutants (2001) | ASC Shrimp, Bonsucro, Fairtrade Standard for Hired Labour, FT Small Producers Organizations, FT Trader, Union for Ethical Biotrade, 4C-GCP |

| Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (1998) | |

| United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs (1961) | |

| United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances (1971) | |

| United Nations Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (1988) | |

| United Nations Convention against Corruption (2004) |

| Current | Armenia, Bolivia, Cape Verde, Mongolia, Pakistan, Paraguay, Philippines (since December 2014), Kyrgyzstan (since February 2016) and Sri Lanka (since May 2017) |

| Left | Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Panama, Peru (exit January 2016), Georgia (exit January 2017) |

| GSP+ Country | Agricultural Products | Cereals | Dried Fruits | Fibres | Fresh Fruits | Horticulture | Herbs and Spices | Livestock | Nuts and Oilseeds | Beverages | Fruit Juice | Construction | Electronics | Energy | Fishing | Enhanced Fishing | Wildstock | Aquarium |

| Armenia | 20 | 16 | 15 | 13 | 18 | 18 | 16 | 13 | 16 | 13 | 13 | 9 | 11 | 9 | 14 | 14 | 11 | 11 |

| Bolivia | 39 | 27 | 28 | 25 | 32 | 31 | 29 | 23 | 30 | 23 | 23 | 14 | 16 | 18 | 22 | 22 | 19 | 18 |

| Cape Verde | 13 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 9 | 11 | 9 | 13 | 12 | 12 | 11 |

| Mongolia | 18 | 16 | 16 | 15 | 17 | 15 | 16 | 15 | 17 | 15 | 15 | 11 | 13 | 11 | 15 | 16 | 13 | 13 |

| Pakistan | 35 | 26 | 25 | 25 | 29 | 26 | 27 | 21 | 28 | 23 | 23 | 16 | 19 | 16 | 24 | 26 | 20 | 20 |

| Paraguay | 39 | 28 | 30 | 27 | 32 | 28 | 30 | 24 | 31 | 24 | 24 | 15 | 17 | 19 | 22 | 22 | 20 | 19 |

| Philippines | 19 | 28 | 28 | 27 | 31 | 30 | 29 | 24 | 30 | 23 | 23 | 15 | 18 | 18 | 23 | 23 | 20 | 18 |

| Kyrgyz Rep | 15 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 12 | 13 | 11 | 13 | 14 | 14 | 9 | 11 | 9 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 11 |

| Sri Lanka | 39 | 25 | 26 | 25 | 30 | 30 | 26 | 22 | 26 | 23 | 23 | 15 | 18 | 16 | 23 | 21 | 20 | 18 |

| GSP+ Country | Fertilize | Food Products | Forestry | Timber | Non-Timber | Mining | Handicrafts | Jewellery | Natural ingredients | NI Cosmetics | NI Food Products | Services | Tourism | Textiles | Toys | Wood Products | Consumer Products | |

| Armenia | 9 | 16 | 11 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 9 | 10 | 14 | 11 | 14 | 11 | 9 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 11 | |

| Bolivia | 13 | 27 | 21 | 20 | 20 | 18 | 17 | 14 | 22 | 18 | 22 | 16 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 16 | 17 | |

| Cape Verde | 8 | 13 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 12 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 12 | |

| Mongolia | 10 | 16 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 14 | 12 | 11 | 14 | 12 | 14 | 13 | 11 | 14 | 12 | 11 | 14 | |

| Pakistan | 15 | 28 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 20 | 19 | 16 | 20 | 17 | 20 | 18 | 18 | 24 | 18 | 17 | 20 | |

| Paraguay | 14 | 29 | 21 | 21 | 20 | 19 | 18 | 15 | 21 | 18 | 21 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 18 | 17 | 19 | |

| Philippines | 14 | 28 | 21 | 21 | 20 | 19 | 18 | 15 | 22 | 18 | 22 | 17 | 18 | 23 | 17 | 9 | 18 | |

| Kyrgyz Rep | 8 | 15 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 13 | 10 | 9 | 11 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 9 | 11 | 10 | 18 | 12 | |

| Sri Lanka | 14 | 27 | 20 | 20 | 19 | 20 | 19 | 16 | 19 | 16 | 19 | 17 | 18 | 23 | 19 | 19 | 18 |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marx, A. Integrating Voluntary Sustainability Standards in Trade Policy: The Case of the European Union’s GSP Scheme. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4364. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124364

Marx A. Integrating Voluntary Sustainability Standards in Trade Policy: The Case of the European Union’s GSP Scheme. Sustainability. 2018; 10(12):4364. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124364

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarx, Axel. 2018. "Integrating Voluntary Sustainability Standards in Trade Policy: The Case of the European Union’s GSP Scheme" Sustainability 10, no. 12: 4364. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124364

APA StyleMarx, A. (2018). Integrating Voluntary Sustainability Standards in Trade Policy: The Case of the European Union’s GSP Scheme. Sustainability, 10(12), 4364. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124364