Can Creating Shared Value (CSV) and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs) Collaborate for a Better World? Insights from East Asia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. The Beginnings of Creating Shared Value

2.2. Issues of Creating Shared Value

2.3. A Closer Look at Creating Shared Value in Asia

2.4. The Emerging Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

2.5. Research Questions

- (1)

- How and to what extent is CSV perceived in Asia? (Discovery 1);

- (2)

- are there differences in CSV between each Asian nation? Why, if any? (Discovery 2); and

- (3)

- how can CSV–SDGs collaboration contribute to better business and a better Asia? (Suggestion 1).

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Data

3.2. Abduction Approach and Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. East Asian Creating Shared Valueat a Glance: Chaos

4.1.1. Korea and the Creating Shared Value Syndrome

CSV may fade away soon as many companies want to ‘come back to the basic—philanthropy’. Korean businesses do not see any tangible outcome of CSV, and anyway, they should pursue philanthropy under the basic responsibility of business in Korean business culture. (Series of interviews conducted on 17 December 2015, 23 February 2016, and 2 February 2018 with the former Director of CSR Division at one of the Korean conglomerates.)

CSV might be replaced with another new term because Koreans are always chasing for trends (including ideas such as CSV) without critical thinking and future planning. (Series of interviews conducted on 25 February 2015 and 7 March 2017 with the founder and CEO of a non-profit organization in Seoul. She also advises the Korean government on CSR and related policies.)

4.1.2. Japanese Caution against Creating Shared Value

In Japan, traditionally, the rich are called to serve society, and it is all about CSV, which has been embedded in corporate culture, so that CSV is not new in Japan. (An interview conducted on 31 March 2017 with a researcher on Japanese traditional CSR philosophy and culture, and on “Omi Merchant” in particular.)

If a corporation says to Japanese society that it is searching for economic value through social contribution, Japanese people may regard it as arrogant and unethical, which is very dangerous in Japanese context. (Consultation meetings conducted on 28 September 2016 and 26 January 2017 with a government official in Japan.)

4.1.3. Chinese Apathy toward Creating Shared Value

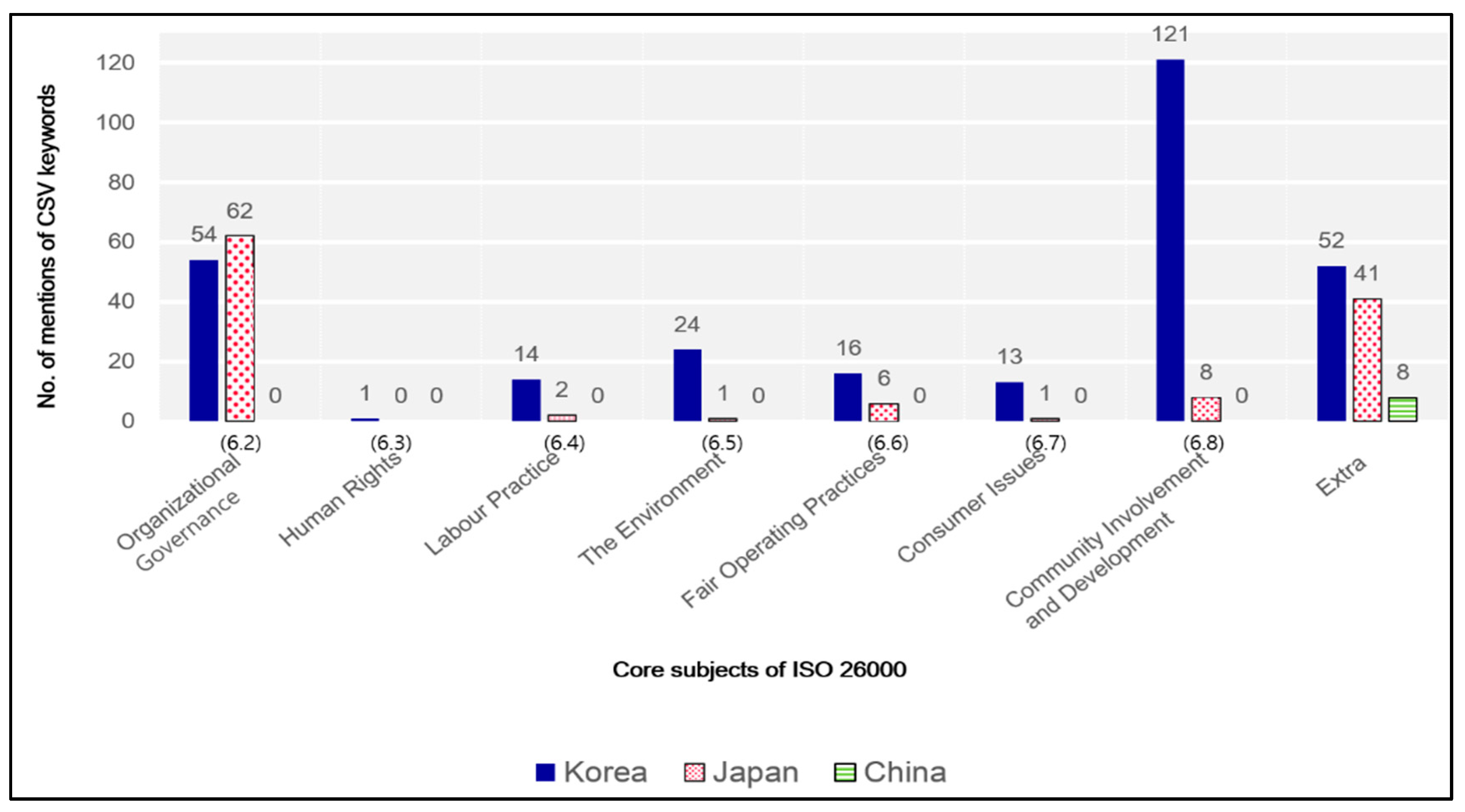

4.2. What Does “Creating Shared Value” Mean in Asia?

CSV is not new to Japanese companies when we compare with American companies. I believe that corporations need to stay with society and to stay with people. To build a relationship with society is the key to Japanese enterprise management. Why is ROI generally lower than America? A company has to pay employees, tax, expenditure to society before the first economic bottom line. (Interview conducted on 8 August 2014 with the General Manager of the CSR Team, one of the biggest trading companies in Japan. He has been leading the CSR policy of the company for many years and recently retired as the head of the CSR Team.)

5. Discussion

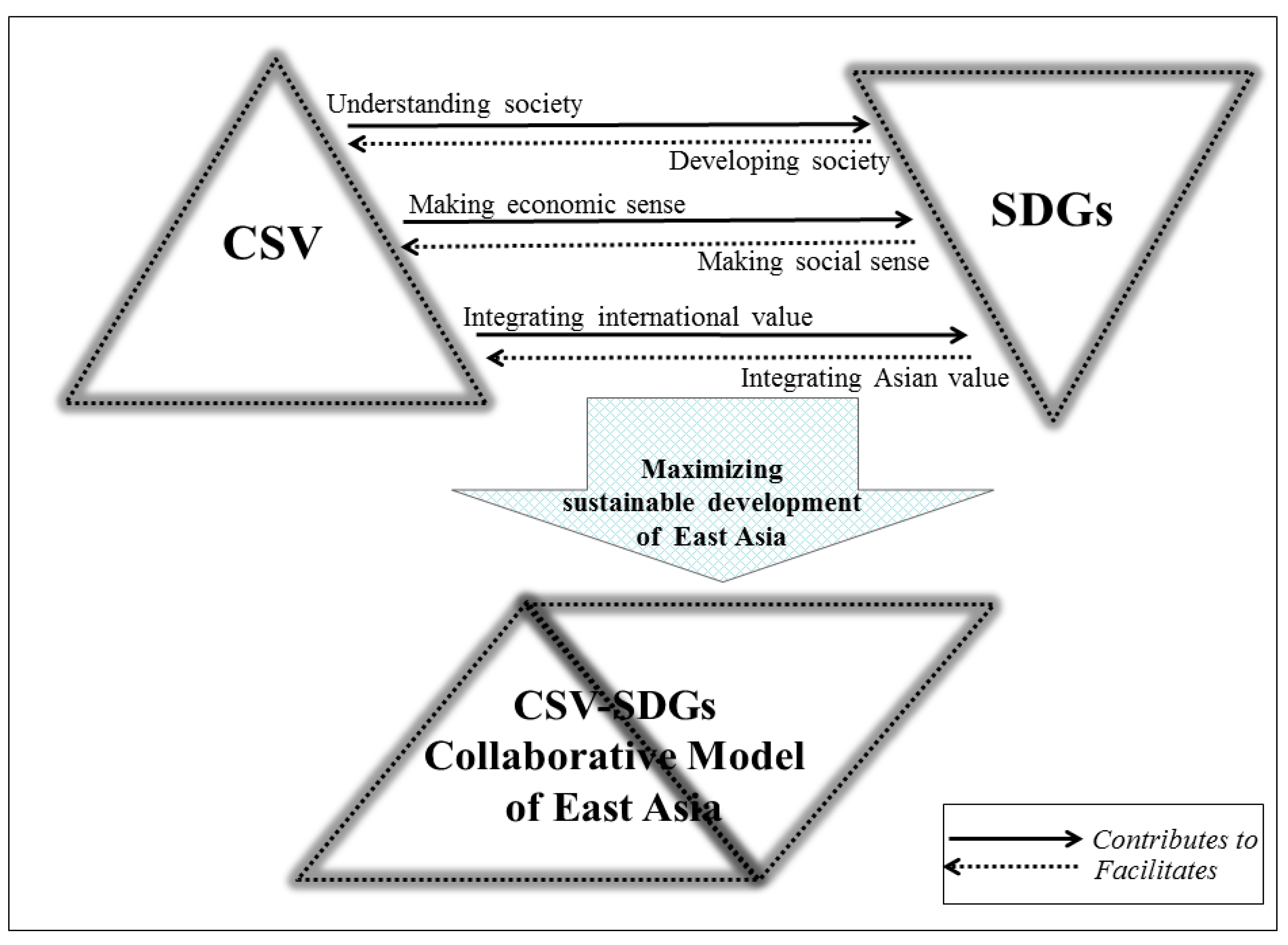

5.1. New Model

5.1.1. Tackling the Gap between Understanding and Developing Society

5.1.2. Encompassing Economic and Social Sensibilities into Business Strategy

5.1.3. Integration of International and Local Values

5.2. New Phenomena

5.2.1. Back to the Basics

5.2.2. New Methodology for Business Survival

5.2.3. Creating Shared Value–Sustainable Development Goals (CSV–SDGs) as a Social Issue

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

6. Final Remarks

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Toyota Motor | 1. Toyota Motor | 1. Toyota Motor | 1. Toyota Motor |

| 2. NTT DoCoMo | 2. Mitsubishi UFJ Financial | -. Softbank (N/A) | 2. Mitsubishi UFJ Financial |

| 3. Nippon Telegraph & Telephone | -. Honda Motor (N/A) | 2. Mitsubishi UFJ Financial | 3. Softbank |

| 4. Mitsubishi UFJ Financial | 3. NTT DoCoMo | -. Honda Motor (N/A) | 4. NTT DoCoMo |

| 5. Canon Inc. | 4. Japan Tobacco | 3. Sumitomo Mitsui Financial | 5. Nippon Telegraph & Telephone |

| -. Honda Motor (N/A) | 5. Nippon Telegraph & Telephone | 4. NTT DoCoMo | 6. KDDI Corp. |

| 6. Japan Tobacco | 6. Canon Inc. | 5. Japan Tobacco | 7. Japan Tobacco |

| 7. Nissan Motor | 7. Sumitomo Mitsui Financial | 6. Nippon Telegraph & Telephone | 8. Honda Motor |

| 8. Sumitomo Mitsui Financial | -. FANUC Corp. (N/A) | 7. KDDI Corp. | 9. Sumitomo Mitsui Financial |

| -. FANUC Corp. (N/A) | 8. Mizuho Financial Group | 8. Mizuho Financial Group | 10. Canon Inc. |

| 9. Takeda Pharmaceutical | 9. Nissan Motor | 9. Denso Corp. | 11. Denso Corp. |

| 10. Mitsubishi Corp. | -. Softbank (N/A) | -. FANUC Corp.(N/A) | 12. Mizuho Financial Group |

| -. Softbank (N/A) | 10. Takeda Pharmaceutical | 10. Fast Retailing Co. | 13. Nissan Motor |

| 11. Mizuho Financial Group | 11. Mitsubishi Estate | 11. Canon Inc. | -. FANUC Corp. (N/A) |

| 12. KDDI Corp. | 12. KDDI Corp. | 12. Mitsubishi Estate | 14. Fast Retailing Co. |

| 13. Mitsui | 13. Mitsubishi Corp. | 13. Nissan Motor | 15. Hitachi |

| 14. East Japan Railway | 14. Denso Corporation | 14. Hitachi | 16. Takeda Pharmaceutical |

| 15. Seven & I Holdings | 15. Hitachi | 15. Takeda Pharmaceutical | 17. Seven & I Holdings |

| 16. Denso Corporation | 16. Mitsui | 16. Seven & I Holdings | 18. Astellas Pharma |

| 17. Hitachi | 17. Fast Retailing Co. | 17. Nippon Steel & Sumitomo Metal | 19. Central Japan Railway |

| 18. Shin-Etsu Chemical | 18. Shin-Etsu Chemical | 18. Mitsui Fudosan | 20. Mitsubishi Corp. |

| 19. Panasonic | 19. East Japan Railway | 19. Mitsubishi Corp. | |

| 20. Mitsubishi Estate | 20. Seven & I Holdings | 20. East Japan Railway |

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Samsung Electronics | Samsung Electronics | Samsung Electronics | Samsung Electronics |

| 2 | Hyundai Motors | Hyundai Motors | Hyundai Motors | Hyundai Motors |

| 3 | POSCO | Hyundai Mobis | SK Hynix | Korea Electric Power |

| 4 | Hyundai Mobis | POSCO | Korea Electric Power | Samsung C & T |

| 5 | Kia Motors | SK Hynix | POSCO | SK Hynix |

| 6 | LG Chemical | NAVER | NAVER | Samsung |

| 7 | Korea Electric Power | Kia Motors | Hyundai Mobis | Amore Pacific |

| 8 | Samsung Life | Shinhan Financial | Shinhan Financial | Kia |

| 9 | Shinhan Financial | Korea Electric Power | Kia | SK Telecom |

| 10 | Hyundai Heavy Industries | Samsung Life | SK Telecom | Hyundai Mobis |

| 11 | SK Hynix | LG Chemical | Samsung Life | Hana Financial Group |

| 12 | SK Innovation | Hyundai Heavy Industries | KB Financial Group | Shinhan Financial |

| 13 | KB Financial Group | SK Telecom | Amore Pacific | LG Display |

| 14 | SK Telecom | KB Financial Group | Samsung Fire & Marine Insurance | LG Chemical |

| 15 | LG Electronics | SK Innovation | SK C & C | NAVER |

| 16 | S-Oil | Hana Financial Group | KT & G | POSCO |

| 17 | LG | Lotte Shopping | LG Chemical | KT & G |

| 18 | LG Display | Samsung Fire & Marine Insurance | LG Display | Samsung Fire & Marine Insurance |

| 19 | KT & G | LG Electronics | LG | KB Financial Group |

| 20 | Lotte Shopping | LG | Samsung C & T | LG Electronics |

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Petrochina | 1. Petrochina | 1. Petrochina | 1. Petrochina |

| 2. Industrial & Commercial Bank of China | 2. Industrial & Commercial Bank of China | 2. Industrial & Commercial Bank of China | 2. Industrial & Commercial Bank of China |

| 3. Bank of China | 3. Bank of China | 3. Agricultural Bank of China | 3. Agricultural Bank of China |

| 4. China Petroleum & Chemical | 4. China Petroleum & Chemical | 4. Bank of China | 4. Bank of China |

| 5. China Shenhua | 5. China Life | 5. China Petroleum & Chemical | -. China Life (N/A) |

| 6. China Life | 6. China Shenhua | 6. China Life | 5. China Petroleum & Chemical |

| 7. China Merchants Bank | 7. China Merchants Bank | 7. China Shenhua | 6. Ping An Insurance |

| -. Kweichow Moutai (N/A) | -. Kweichow Moutai (N/A) | 8. China Merchants Bank | 7. China Merchants Bank |

| 8. Ping An Insurance | 8. Ping An Insurance | 9. Ping An Insurance | 8. China Shenhua |

| 9. Bank of Communications | 9. Industrial Bank | 10. Minsheng Bank | 9. Citic Securities |

| 10. Industrial Bank | 10. Minsheng Bank | 11. Industrial Bank | 10. Industrial Bank |

| 11. Minsheng Bank | 11. SAIC Motor | 12. Pudong Development Bank | 11. Shanghai PuDong Development Bank |

| 12. SAIC Motor | 12. Bank of Communications | -. Kweichow Moutai (N/A) | 12. Minsheng Bank |

| 13. Citic Bank | 13. Pudong Development Bank | 13. SAIC Motor | 13. Shang Automotive |

| 14. Pudong Development Bank | 14. China Pacific Insurance | 14. Bank of Communications | 14. Bank of Communications |

| 15. China Pacific Insurance | 15. Citic Bank | 15. CITIC Securities | -. Kweichow Moutai (N/A) |

| 16. China Unicom | 16. CITIC Securities | 16. Citic Bank | 15. Citic Bank |

| 17. Daqin Railway | 17. China State Construction | 17. China Pacific Insurance | 16. Shanghai International Port |

| 18. CITIC Securities | 18. Daqin Railway | 18. Shanghai International Port | 17. China Pacific Insurance |

| 19. Sany Heavy Industry | 19. Poly Real Estate | 19. Daqin Railway | 18. Daqin Railway |

| 20. Baoshan Iron and Steel | 20. Baoshan Iron and Steel | 20. Everbright Bank | 19. Everbright Bank |

| 20. Yangtze Power |

References

- Zhou, Z.; Nakano, C.; Luo, B.N. Business Ethics as Filed of Training, Teaching, and Research in East Asia. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 104, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, A.; Clarke, A.; Huang, L. Multi-Stakeholder Partnerships for Sustainability: Designing Decision-Making Processes for Partnership Capacity. J. Bus. Ethics 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, R.C.; Moon, J. Dynamics of Corporate Social Responsibility in Asia: Knowledge and Norms. Asian Bus. Manag. 2015, 14, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tong, L.; Takeuchi, R.; George, G. Corporate Social Responsibility: An Overview and New Research Directions. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 534–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.; Kramer, M.R. Creating Shared Value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Crane, A.; Palazzo, G.; Spence, L.J.; Matten, D. Contesting the Value of “Creating Shared Value”. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2014, 56, 130–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voltan, A.; Hervieux, C.; Mills, A. Examining the Win-Win Proposition of Shared Value across Contexts: Implications for Future Application. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2017, 26, 347–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.D.; An, H.-T.; Myung, J.K.; Bae, S.M. Assessing CSV as a Successful Strategic CSR. Korea Bus. Rev. 2016, 20, 291–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, M.M.; Bergman, Z.; Berger, L. An Empirical Exploration, Typology, and Definition of Corporate Sustainability. Sustainability 2017, 9, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voegtlin, C.; Scherer, A.G. Responsible Innovation and the Innovation of Responsibility: Governing Sustainable Development in a Globalized World. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 143, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberger, P.A.; Pratt, M.G. Moving Forward by Looking Back: Reclaiming Unconventional Research Contexts and Samples in Organizational Scholarship. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 665–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberger, P.A. AMD—Clarifying What We Are about and Where We Are Going. Acad. Manag. Discov. 2018, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thagard, P.; Shelley, C. Abductive Reasoning: Logic, Visual Thinking, and Coherence. In Logic and Scientific Methods; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1997; pp. 413–427. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, M. The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits. The New York Times Magazine, 19 September 1970; 122–124. [Google Scholar]

- Wieland, J. Creating Shared Value: Concepts, Experience, Criticism; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; Capstone: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Dunning, J.H. Making Globalization Good: The Moral Challenges of Global Capitalism; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Reich, R.B. Supercapitalism: The Battle for Democracy in an Age of Big Business; Icon: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-184831-007-0. [Google Scholar]

- Harvard Magazine. Bill Gates on “Creative Capitalism” (13 October 2008). Available online: http://harvardmagazine.com/2008/10/bill-gates-on-creative-capitalism (accessed on 14 August 2017).

- Corner, P.D.; Pavlovich, K. Shared Value through Inner Knowledge Creation. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 135, 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyllick, T. The Opposing Perspectives on Creating Shared Value. Financial Times, 20 April 2014. [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D.; Wright, P.M. Corporate Social Responsibility: Strategic Implications. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matten, D.; Moon, J. “Implicit” and “Explicit” CSR: A Conceptual Framework for a Comparative Understanding of Corporate Social Responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 404–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestle. Contributing to the Global Goals 2018. Available online: https://www.nestle.com/csv/what-is-csv/contribution-global-goals (accessed on 10 July 2018).

- Dembek, K.; Singh, P.; Bhakoo, V. Literature Review of Shared Value: A Theoretical Concept or a Management Buzzword? J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 137, 231–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S. Michael Porter Is a Pirate. ManagementNext. 10/1 (January 2013). Available online: http://managementnext.com/pdf/2013/MN_Jan_2013.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2017).

- Carroll, A.B. Corporate social responsibility: The centerpiece of competing and complementary frameworks. Organ. Dyn. 2015, 44, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfitzer, M.; Bockstette, V.; Stamp, M. Innovating for Shared Value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2013, 91, 101–107. [Google Scholar]

- Moss, M. Salt, Sugar, Fat: How the Food Giants Hooked Us; Random House Trade Paperbacks: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Badaracco, J.L. Defining Moments: When Managers Must Choose between Right and Right; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D.; Mayer, R.C.; Tan, H.H. The Trusted General Manager and Business Unit Performance: Empirical Evidence of a Competitive Advantage. Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 563–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beschorner, T. Creating Shared Value: The One-Trick Pony Approach. Bus. Ethics. J. Rev. 2013, 1, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De los Reyes, G.; Scholz, M.; Smith, N.C. Beyond the “Win-Win”: Creating Shared Value requires ethical frameworks. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2017, 59, 142–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, L.P.; Werhane, P.H. Proposition: Shared Value as an Incomplete Mental Model. Bus. Ethics J. Rev. 2013, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovring, C.M. Corporate social responsibility as shared value creation: Toward a communicative approach. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2017, 22, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noronha, C. Culture and Business in Asia. In Asian Business & Management: Theory, Practice and Perspectives; Hasegawa, H., Noronha, C., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2009; pp. 101–123. [Google Scholar]

- Barr, M.D. Lee Kuan Yew and the “Asian Values” Debate. Asian Stud. Rev. 2000, 24, 309–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodpaster, K.E.; Matthews, J.B. Can a corporation have a conscience? Harv. Bus. Rev. 1982, 60, 132–141. [Google Scholar]

- Paine, L.S. Value Shift: Why Companies Must Merge Social and Financial Imperatives to Achieve Superior Performance; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Takashi, N. Creating Shared Value for Management Innovation; Toyo Keizai Inc.: Tokyo, Japan, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Juslin, K. The Impact of Chinese Culture on Corporate Social Responsibility: The Harmony Approach. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 88, 433–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Soto, H. The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Carney, M.; Gedajlovic, E.; Yang, X. Varieties of Asian capitalism: Toward an institutional theory of Asian enterprise. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2009, 26, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amsden, A. Asia’s Next Giant: South Korea and Late Industrialization; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Nolan, J.; Rowley, C.; Warner, M. Business Networks in East Asian Capitalisms, 1st ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, D.C. Transaction Costs and Crony Capitalism in East Asia. Comp. Politics 2003, 35, 439–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, M.A.; Redding, G. The Oxford Handbook of Asian Business Systems; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, D.W.; Kim, K.B.; Lee, S.M. Impact of the creating shared value’s motivation and performance on the stakeholders. J. Corp. Manag. 2015, 22, 153–174. [Google Scholar]

- Blanc, D.L. Towards Integration at Last? The Sustainable Development Goals as a Network of Targets. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 23, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedd, G.; The UN Has Started to Talk Business. Financial Times, 22 September 2017. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/11b19afc-9d97-11e7-9a86-4d5a475ba4c5 (accessed on 28 September 2018).

- The Economist. Meeting the SDGs: A Global Movement Gains Momentum. Available online: https://eiuperspectives.economist.com/sites/default/files/Meeting%20the%20SDGs_A%20global%20movement%20gains%20momentum.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2018).

- Kumar, S.; Kumar, N.; Vivekadhish, S. Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Addressing Unfinished Agenda and Strengthening Sustainable Development and Partnership. Indian J. Commun. Med. 2016, 41, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. Nestlé Commits to Expanding Nutrition Education to Teenage Girls in All Its Milk Villages in India to Help Increase Their Knowledge about Good Nutrition and Healthy Diets. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/partnership/?p=1231 (accessed on 2 October 2018).

- Allianz. Reposing to Tomorrow’s Challenge. Available online: https://www.allianz.com/en/sustainability/strategy-and-governance/un-sdgs-and-allianz/ (accessed on 27 September 2018).

- Eccles, B. UN Sustainable Development Goals: Good for Business. Forbes. 20 October 2015. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/bobeccles/2015/10/20/un-sustainable-development-goals-good-for-business/#d1aca222b50c (accessed on 28 September 2018).

- Ethical Corporation. Risk of ‘SDG Wash’ as 56% of Companies Fail to Measure Contribution to SDGs. Available online: http://www.ethicalcorp.com/risk-sdg-wash-56-companies-fail-measure-contribution-sdgs (accessed on 30 September 2018).

- Mueller, J. Finding New Kinds of Needles in Haystacks: Experimentation in the Course of Abduction. Acad. Manag. Discov. 2018, 4, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebiringa, O.T.; Yadirichukwu, E.; Chigbu, E.E.; Obi Joseph Ogochukwu, O.J. Effect of Firm Size and Profitability on Corporate Social Disclosures: The Nigerian Oil and Gas sector in Focus. Br. J. Econ. Manag. Trade 2013, 3, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peong, Y.-S.; Dashdeleg, A.-U. Nonlinear Relationships between R&D, Firm Size and Corporate Social Responsibility. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2015, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickert, C.; Scherer, S.G.; Spence, L.J. Walking and Talking Corporate Social Responsibility: Implications of Firm Size and Organizational Cost. J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 53, 1169–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, L.J. Small Business Social Responsibility. Bus. Soc. 2016, 55, 23–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marano, V.; Tashman, P.; Kostova, T. Escaping the Iron Cage: Liabilities of Origin and CSR Reporting of Emerging Market Multinational Enterprises. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2017, 48, 386–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S. Building a New Institutional Infrastructure for Corporate Responsibility. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2008, 22, 87–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapple, W.; Herzig, C.; Slager, R.C. The Dynamics of Corporate Social Responsibility in Asia: A 6 Country Study. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortanier, F.; Kolk, A. On the Economic Dimensions of Corporate Social Responsibility. Bus. Soc. 2007, 46, 457–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marano, V.; Kostova, T. Unpacking the Institutional Complexity in Adoption of CSR Practices in Multinational Enterprises. J. Manag. Stud. 2015, 53, 28–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KPMG. The KPMG Survey of Corporate Responsibility Reporting 2013, KPMG International 2013. Available online: https://home.kpmg.com/ru/en/home/insights/2013/12/the-kpmg-survey-of-corporate-responsibility-reporting-2013.html (accessed on 15 March 2017).

- KPMG. Sustainability and Reporting Trends in 2025—Preparing for the Future. May 2015. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/resourcelibrary/Sustainability-and-Reporting-Trends-in-2025-1.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2017).

- Chapple, W.; Moon, J. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in Asia: A Seven-Country Study of CSR Web Site Reporting. Bus. Soc. 2005, 44, 415–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Brink, T.W.M.; van den Woerd, F. Industry Specific Sustainability Benchmarks: An ECSF Pilot Bridging Corporate Sustainability with Social Responsible Investments. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 55, 87–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbohn, K.; Walker, J.; Loo, H.Y.M. Corporate social responsibility: The link between sustainability disclosure and sustainability performance. Abacus 2014, 50, 422–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behfar, K.; Okhuysen, G.A. Perspective Discovery within validation logic: Deliberately surfacing, complementing and substituting abductive reasoning in hypothetico-deductive inquiry. Organ. Sci. 2018, 29, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeb, D.; Sakakibara, M.; Mahmood, I. From the Editors: Endogeneity in international business research. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2012, 43, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M.; Whited, T. Endogeneity in Corporate Finance; Working Paper; Wharton: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Issa, A. The Factors Influencing Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2017, 11, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, A.; García de los Salmones, M.D.M.; López, C. Corporate Reputation in The Spanish Context: An Interaction Between Reporting to Stakeholders and Industry. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 129, 733–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Turunen, H.; Bondas, T. Content Analysis and Thematic Analysis: Implications for Conducting a Qualitative Descriptive Study. Nurs. Health. Sci. 2013, 15, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grbich, C. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Introduction, 1st ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, H.Z. Empirical Research on the Relationship between Board Governance and Corporate Performance [Gongxiang jiazhi yu qiye jixiao guanxi yanjiu]. Xibu Luntan 2015, 23, 102–108. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, D.D. Four basic principles of creating shared value [Chuangzao gongxiang jiazhi de sixiang jiben yuanze]. WTO Jingji Daokan 2016, 3, 34. [Google Scholar]

- Marquis, C.; Yang, Z. Embracing shared value in China [Zhongguo yingjie “gongxiang jiazhi” shidai]. Zhongguo Jingji Baogao 2014, 7, 115–116. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, R. ISO 26000 and the Standardization of Strategic Management Processes for Sustainability and Corporate Social Responsibility. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2012, 22, 442–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueckenberger, U.; Jastram, S. Transnational Norm-Building Networks and the Legitimacy of Corporate Social Responsibility Standards. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprar, D.V. Foreign Locals: A Cautionary Tale on the Culture of MNC Local Employees. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2011, 42, 608–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Park, K. Cooperation between large and small companies—Focused on Creating Shared Value (CSV) perspectives. Prod. Rev. 2015, 29, 253–275. [Google Scholar]

- Boardman, C.M.; Kato, H.K. The Confucian Roots of Business Kyosei. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 48, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaku, R. The path of Kyosei. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1997, 75, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fortune. China’s Global 500 Companies Are Bigger than Ever—And Mostly State-Owned. Fortune (22 July 2015). Available online: http://fortune.com/2015/07/22/china-global-500-government-owned/ (accessed on 17 March 2017).

- Chen, H.; Li, X.; Zeng, S.; Ma, H.; Lin, H. Does State Capitalism Matter in Firm Internationalization? Pace, Rhythm, Location Choice, and Product Diversity. Manag. Decis. 2016, 54, 1320–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Yoshikawa, T. Contingent Value of Director Identification: The Role of Government Directors in Monitoring and Resource Provision in an Emerging Economy. Strateg. Manag. J. 2016, 37, 1787–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsung. Samsung Electronics Sustainability Report 2013. Available online: https://www.samsung.com/us/smg/content/dam/samsung/us/aboutsamsung/2017/about-us-sustainability-report-and-policy-sustainability-report-2013-en.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2018).

- Hyundai. 2013 Hyundai Motor Global Social Contribution Activities White Paper. Available online: https://csr.hyundai.com/upfile/report/scw/SocialContributionActivitiesWhitePaper(ENG)_2013.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2018).

- SKT. SK Telecom Annual Report 2013. Available online: https://www.sktelecom.com/img/kor/persist_report/20140806/SUSTAIN_REPORT_2013_ENG.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2018).

- Samsung Life Insurance. 2014 Samsung Life Insurance Integrated Report. Available online: http://www.samsunglife.com/companyeng/sustainability/report/report.html (accessed on 10 June 2018).

- Mitsubishi. Mitsubishi Estate Group CSR Report 2013. Available online: http://www.mec.co.jp/e/csr/csrreport/pdf/2013/csr2013_e.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2018).

- Xing, L.; Shaw, T.M. The Political Economy of Chinese State Capitalism. J. Chin. Int. Relat. 2013, 1, 88–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiss, S. From Implicit to Explicit Corporate Social Responsibility: Institutional Change as a Fight for Myths. Bus. Ethics Q. 2009, 19, 433–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthaud-Day, M.L. Transnational Corporate Social Responsibility: A Tri-Dimensional Approach to International CSR Research. Bus. Ethics Q. 2005, 15, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, R.C.; Yoo, K.I.; Uddin, H. The Korean Air nut rage scandal: Domestic versus international responses to a viral incident. Bus. Horiz. 2018, 61, 522–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoek, M. CSV and the SDGs—Creating Shared Value Meets the Sustainable Development Goals. 2017. Available online: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/csv-and-the-sdgs-creating-shared-value-meets-the_us_58eb9ceae4b0acd784ca5a63 (accessed on 1 October 2018).

- Kim, C.H.; Amaeshi, K.; Harris, S.; Suh, C.-J. CSR and the National Institutional Context: The Case of South Korea. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 2581–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, C.K. CSR and CSV (Creating Shared Value). Corp. Gov. Rev. 2013, 66, 57–66. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. Cultures Consequences: International Differences in Work-Relates Values; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1980; ISBN 0-8039-1306-0. [Google Scholar]

- Katzenstein, P.J.; Shiraishi, T. Network Power: Japan and Asia; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1997; ISBN 0-8014-3314-2. [Google Scholar]

- Handy, C. What’s a business for? Harv. Bus. Rev. 2002, 80, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Smith, J. Globalization and transnational social movement organizations. In Social Movements and Organizational Theory; Davis, G.F., Mcadam, D., Scott, W.R., Zald, M.N., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 226–248. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, G.; Moran, P. Corporate Reputations: Built in or Bolted on? Calif. Manag. Rev. 2012, 54, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangan, K.; Chase, L.; Karim, S. The truth about CSR. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2015, 93, 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Illia, L.; Zyglidopoulos, S.C.; Romenti, S.; Rodríguez-Cánovas, B.; del Valle Brena, A.G. Communicating Corporate Social Responsibility to a Cynical Public. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2013, 54, 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, J.C.; Mintzberg, H. Why Corporate Social Responsibility Isn’t a Piece of Cake. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2015, 56, 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- ISO. ISO 26000 and SDGs. 2016. Available online: https://www.iso.org/files/live/sites/isoorg/files/archive/pdf/en/iso_26000_and_sdgs.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2018).

- Gao, Y. Corporate Social Performance in China: Evidence from Large Companies. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 89, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, R.C. Can Creating Shared Value (CSV) and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs) Collaborate for a Better World? Insights from East Asia. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4128. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114128

Kim RC. Can Creating Shared Value (CSV) and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs) Collaborate for a Better World? Insights from East Asia. Sustainability. 2018; 10(11):4128. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114128

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Rebecca Chunghee. 2018. "Can Creating Shared Value (CSV) and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs) Collaborate for a Better World? Insights from East Asia" Sustainability 10, no. 11: 4128. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114128

APA StyleKim, R. C. (2018). Can Creating Shared Value (CSV) and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs) Collaborate for a Better World? Insights from East Asia. Sustainability, 10(11), 4128. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114128