1. Introduction

In recent years, a business ecosystem has been changed rapidly by the new era like an information society and knowledge economy. Since the numerous information and knowledge exist all around our society and economy, consumers can easily gather and access their own customized information for buying goods and services. Moreover, amid the accelerated development of information and communication technologies (ICTs), the boundary of a market for goods and services is no longer limited in the off-line and online marketplaces, but it has extended to the mobile market [

1,

2,

3]. In this situation, firms are required to establish new management strategies for their sustainable business development [

4]. The general strategies for firms’ sustainable business development or sustainable growth can be recognized by several definitions and concepts such as making certified business purposes, utilizing collaborations with external partnerships, enhancing innovation activities, etc. However, the most important matter is how the firm can realize the strategies for their sustainable business models amid the enormous and irregularly scattered information. Especially for the case of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), they generally cannot afford to build a system or organization for responding new market conditions and facilitating strategy management. For that reason, SMEs usually handle and solve their business problems through advising services from external experts, in which situation is called business or management consulting.

One of the main issues in business consulting, in which the topic areas include business strategies, management of human resources, finance and accounting, improvement of production and process, IT system, total quality management (TQM), and so on, concerns what are the effective factors for the completion of consulting projects and how the results affect the business performance of the consulting client firms. In recent years, numerous studies have explored the structure of the consulting process and the methodology of consulting models [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. These studies have contributed to the understanding that consulting leads to the positive business performance and commercial innovation as well as sustainable business development. The importance of business consulting has been addressed by researchers for only a few decades. Of particular importance in this regard is the potential of business consulting as knowledge-based activities and services to affect both revitalization of small and medium-sized enterprises directly and preparation of the new industrial revolution indirectly [

12,

13,

14].

In a variety of circumstances, however, the effect of consulting results on business performance is hard to evaluate by a one-dimensional analysis, which focuses on one-sided perspective such as either details of consultant competency or environments of consulting client firms. In order to analyze the consulting models without loss of generality, one should take into account consultant competency, consulting environment of client firms, and innovation activities of client firms simultaneously. From the previous studies, consultant competency generally has a positive impact on the completion of consulting projects [

5,

8,

9,

10,

15] and is positively related to the business performance of client firms [

9,

11,

16]. Moreover, the consulting environment of client firms, such as institutional conditions, commitment and willingness of CEOs to participate, and so on, are also important to the completion of consulting projects and the contribution to the business performance [

16,

17,

18].

Furthermore, with regard to the innovation systems of consulting client firms, understanding the effects of their innovation activities on business performance improves the sophistication of analysis of consulting models [

19,

20]. Although the innovation activities, which consists of knowledge-based activities and capabilities, can neither be codified nor standardized (a.k.a. tacit knowledge), it has been much paid attention to by many researchers, industrial stakeholder, and even policy makers for understanding the importance of research and development (R and D) and creating a new technology and process [

21,

22]. In general, the proxy variables of innovation activities such as exploration and exploitation for seeking new knowledge and utilizing existing knowledge, respectively [

23,

24,

25] are the most useful indicators for solving the puzzle of the consulting process and evaluating a firm’s innovation system that contributes to the business performance [

26,

27,

28,

29]. However, due to the innovation ambidexterity, it is highly probable that the relationships between innovation activities and consulting factors have somewhat different impacts on the consulting performance. In other words, firms should consider not only to utilize and refine their existing knowledge and resources but also to seek new knowledge and future changing demand in the market [

23,

27,

28,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34], so it requires to establish the different consulting strategies and plans across the different innovation activities like exploration and exploitation. Moreover, this innovation ambidexterity can be also used to establish sustainable business development strategies for firms, but the two components of innovation ambidexterity, exploration and exploitation, have different impacts on the firm’s strategies. While exploration makes it possible to establish the firm’s long-term and distant search strategies, exploitation is to provide the firm’s short-term and local search strategies [

35].

In this study, we explore the strategies for sustainable business development via the process and performance of business consulting by using a survey with 200 samples across the different industries in South Korea. In so doing, we build upon the structural equation model for the consulting model framework and attempt to analyze the relationships between consulting factors and consulting performance via the characteristics of innovation activities such as exploration and exploitation (and ambidexterity). There are several research questions in this paper: what are the relationships between the consultant competency and the innovation activities; how do these relationships differ for the different types of innovation activities; also what are the relationships between the consulting environment of client firms and innovation activities via the role of CEOs and their institutional conditions for consulting projects; how do these relationships differ for the different types of innovation activities; how do the innovation activities affect the business performance through the consulting process and performance; which consulting factors have higher impact on the contribution to business performance; if so how do the factors affect the strategies for sustainable business development? Moreover, this paper has the following research purposes: (1) to build the consulting model framework, which will be used for establishing strategies for sustainable business development; (2) to analyze the relationships between consulting factors and consulting performance through innovation activities for finding the key variables in the model, which might affect the firms’ business performance and the strategies for sustainable business development; (3) to provide and suggest implications for the sustainable growth of firms with regard of innovation ambidexterity.

The rest of this paper is organized into five sections.

Section 2 reviews previous studies of business consulting and innovation activities, and derives key research hypotheses.

Section 3 develops conceptual model frameworks and describes the model methods.

Section 4 shows results of the model hypotheses and path coefficient analysis. Moreover, this section also provides the importance-performance mapping analysis (IPMA).

Section 5 discusses the strategies for sustainable business development.

Section 6 summarizes the main conclusions and insights of this paper, and discusses shortages and further studies.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Characteristics of Innovation Activities

There are several different types of innovation activities in the firm, but as mentioned previous section, this paper uses exploration and exploitation as proxy variables for innovation activities. Historically, the concepts of exploration and exploitation are almost firstly introduced by March [

23]. This seminal paper has been generating numerous studies related with innovation techniques [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]. First of all, the general definition of exploration presents one aspect of characteristics of innovation which includes the ability to search for new knowledge, experimentation, variation, risk-loving, future demand, emerging markets, and so on [

23,

24,

28,

31,

33,

42]. In contrast, exploitation, which is also known as another aspect of characteristics of innovation, is defined as the ability to utilize for existing knowledge, efficiency, risk-neutral or risk-avoiding, refinement of original resources, and so on [

23,

26,

27,

28,

30,

32]. According to Benner and Tushman [

35], exploitation has characteristics for local search, which can be measured by knowledge used in previous innovation, whereas exploration generally shows the attribution of distant search, which can be measured by knowledge to be used for further innovation Moreover, following Bierly and Daly [

32], exploration and exploitation are usually distinct, but they have complementary constructs. The relationship between exploration and organizational performance is linear and it has a more impact on dynamic and high-technology environments, whereas the relationship between exploitation and organizational performance is concave and it has a more impact on stable and high-technology environments. Therefore, using the binary concepts of innovation techniques simultaneously are sometimes called “innovation ambidexterity.” With regard of the innovation ambidexterity, the most of firms generally require to pursue organizational ambidexterity that has a balance between the two distinguished types of innovation techniques, such as exploration and exploitation [

35,

41,

43].

Although ambidexterity is the ability to use both exploration and exploitation simultaneously, many of recent studies has shown contradicting results from organizational ambidexterity. This phenomenon is called “ambidexterity as a paradox” [

37,

39,

40,

43]. According to Benner and Tushman [

37,

43], within the context of dynamic capabilities, exploratory and exploitative activities are originated from the same root, but the process management activities are likely to have more beneficial for organizations in stable circumstances (with exploitation) even though these activities must be buffered from exploration, which shows the inconsistent results of ambidextrous activities. Similarly, Koryak et al. [

39] shows that utilizing exploration and exploitation simultaneously, such as organizational ambidexterity, can cause persistent organizational conflicts and tensions. Despite of paradoxical problems of innovation ambidexterity, it is highly probable that there still exists a positive relationship between innovation process and ambidexterity performance [

36,

38,

40]. Moreover, according to Martini et al. [

41], the synergic combination between exploration and exploitation makes it possible to foster a synergic combination between operational efficiency and strategic flexibility. Therefore, when conducting consulting projects, the two different types of innovation activities, exploration and exploitation, should be considered appropriately. Moreover, it also requires to consider balancing trade-off relationships between exploration and exploitation for achieving successful consulting projects and for improving business performance.

2.2. Consultant Competency and Innovation Activities

According to Kubr [

10], management or business consulting is an independent professional advisory service for achieving the business purposes and objectives of companies or organizations by solving their business problems. By the definition, business consulting is one of the most important sources for creating a new knowledge or improving existing technologies in the firms. In order to achieve the business purposes and objectives in the consulting client firms, the consultant competency plays a significant role in the consulting projects [

8,

9,

10,

11,

15]. Consultants generally lead the whole consulting project from beginning to end, and empower the client firms by advising and analyzing their existing problems [

10,

18,

44]. Moreover, Consultants also advice and help the client firms to take new technology or business opportunities in the market [

10,

15]. Since the consultant is the key factor in the consulting projects, the completion or quality of consulting projects can be depended upon the consultant competency [

11,

15,

16,

17,

18,

45]. Analogously, the consultant competency, especially task competency, which is to utilize consulting skills and methods, solving problems, planning consulting strategies, gathering and to apply information, demonstrating written and oral communication, etc., significantly affects not only the completion of consulting projects but the contribution to business performance via the innovation system in the client firms [

5,

6,

7,

9,

16,

46].

Moreover, it is also important to take into account the relationships between consultant competency and innovation activities in client firms across the different types of innovation activities, such as exploration and exploitation [

23,

44,

45]. As shown in previous section, exploration is defined as the ability to seek for new knowledge, risk-taking, flexibility, discovery from new information and resources. Therefore, consultant competency, especially task competency, generally takes into account the ability to establish new business strategies and to provide the knowledge and information required for pioneering new market opportunities when working consulting projects with consulting client firms. This competency makes it possible to enhance the firm’s innovation activities associated with exploration. Analogously, during the consulting projects, the task competency of consultants also can increase the ability of consulting client firms to utilize existing technology and resources for producing new products and new processes. This ability is highly associated with the firm’s innovation activities related with exploitation. Moreover, this logic and theoretical background can confirm whether or not the task competency of consultant has innovation ambidexterity. Therefore, we can generate the research hypotheses as below.

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Task competency of consultants has a positive relationship with exploration.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Task competency of consultants has a positive relationship with exploitation.

2.3. Consulting Environment of Client Firms and Innovation Activities

The consulting environments of client firms are generally consisted of two parts: one is CEO’s support and their decision making for consulting projects; another is the firm’s institutional conditions for consulting projects [

15,

16]. Due to this, these two factors arguably affect not only the completion of consulting projects but the contribution to firms’ business performance [

5,

6,

7,

8,

10]. However, the characteristics and effects of these two consulting environmental factors on the structural relationships with other variables are somewhat different. Relatively, the CEOs’ support is more significant than the institutional conditions due to the influence of leader or executive board [

6,

13]. Additionally, the support of CEOs and their decision making tends to affect their companies’ institutional conditions both explicitly and implicitly [

15]. In consulting environment of client firms, the support of CEOs plays a significant role in their innovation activities for both consulting projects and business performance. However, finding a relationship between the support of CEOs and their innovation activities is generally somewhat difficult because of complication of innovation systems in the firm [

8,

9,

10,

11,

15,

16]. Nevertheless, the support of CEOs for consulting projects can have a positive impact on the firm’s innovation activities. In particular, the support of CEOs to use existing resources and information for consulting projects can also have a positive impact on the firm’s exploitative activities within their innovation system. Likewise, in terms of exploratory activities, the support of CEOs is more likely to empower the ability to seek for new knowledge and discovery of new market opportunities. Moreover, analyzing the relationship between the support of CEOs and institutional conditions is structured around the influence of CEOs’ decision making on the team organization and the system of innovation in the firm. Hence, the support of CEOs can affect the institutional conditions through their understanding and commitment for the consulting projects as well as financial support [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Thus, we can set up the research hypotheses as below.

The consulting environments of client firms are generally consisted of two parts: one is CEO’s support and their decision making for consulting projects; another is the firm’s institutional conditions for consulting projects [

15,

16]. Due to this, these two factors arguably affect not only the completion of consulting projects but the contribution to firms’ business performance [

5,

6,

7,

8,

10]. However, the characteristics and effects of these two consulting environmental factors on the structural relationships with other variables are somewhat different. Relatively, the CEOs’ support is more significant than the institutional conditions due to the influence of leader or executive board [

6,

13]. Additionally, the support of CEOs and their decision making tends to affect their companies’ institutional conditions both explicitly and implicitly [

15]. In consulting environment of client firms, the support of CEOs plays a significant role in their innovation activities for both consulting projects and business performance. However, finding a relationship between the support of CEOs and their innovation activities is generally somewhat difficult because of complication of innovation systems in the firm [

8,

9,

10,

11,

15,

16]. Nevertheless, the support of CEOs for consulting projects can have a positive impact on the firm’s innovation activities. In particular, the support of CEOs to use existing resources and information for consulting projects can also have a positive impact on the firm’s exploitative activities within their innovation system. Likewise, in terms of exploratory activities, the support of CEOs is more likely to empower the ability to seek for new knowledge and discovery of new market opportunities. Moreover, analyzing the relationship between the support of CEOs and institutional conditions is structured around the influence of CEOs’ decision making on the team organization and the system of innovation in the firm. Hence, the support of CEOs can affect the institutional conditions through their understanding and commitment for the consulting projects as well as financial support [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Thus, we can set up the research hypotheses as below.

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Support of CEOs has a positive relationship with exploration.

Hypothesis 4 (H4). Support of CEOs has a positive relationship with exploitation.

Hypothesis 5 (H5). There is a positive relationship between support of CEOs and institutional conditions.

Moreover, the firms’ institutional conditions for consulting projects are highly associated with their innovation system. If the firms’ innovation system has a more hierarchical structure, their degree of autonomy and competency of knowledge adoption and management from external resources are probably low, but if their system tends to pursue a network or team-based system, they have a higher degree of autonomy and absorptive capability [

47,

48]. Moreover, it is highly probable that institutional conditions have more direct impacts on their innovation activities than the support of CEOs even though it has a structural relationship with the support of CEOs’ role and support [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

15,

16]. By and large, the institutional conditions are more likely to relate their innovation activities and their effects on both exploration and exploitation are probably similar. One of the important institutional conditions of the consulting client firm is that it involves the innovation system and culture for encouraging consulting engagement and seeking new knowledge. This innovation system and culture are highly associated with their exploratory activities [

49,

50,

51]. Moreover, the institutional conditions also take into account the system of conducting innovation activities and the internal resources to use the consulting projects. These conditions make it possible to utilize existing knowledge and resource for inducing innovation, and to connect the characteristics of exploitation [

52]. Hence, we can derive the research hypotheses below.

Hypothesis 6 (H6). Institutional conditions have a positive relationship with exploration.

Hypothesis 7 (H7). Institutional conditions have a positive relationship with exploitation.

2.4. Innovation Activities and Business Performance

Most knowledge-based firms and private sectors are engaged in their commercial or industrial innovation. Moreover, their innovation activities are highly collaborated with other entities, especially public sectors like universities and public research centers [

22,

53]. According to Siren et al. [

42], although there is not much empirical evidence that the direct effects of exploration and exploitation on the firms' profit performance because those are generally recognized as mediating constructs, those are still the core elements of firm’s business strategies and innovation performance [

54]. Moreover, following previous studies, the exploration and exploitation are basically connected with the process of innovation and slack resources [

23,

24,

25,

55,

56]. Since exploration and exploitation can be defined as opportunity-seeking and advantage-seeking, respectively [

42,

57,

58,

59], those are affiliated with the firms’ innovation system and affect their business performance [

23,

24,

25,

56,

60,

61]. Yet, each exploration and exploitation seems to have different impacts on contribution to business performance. If both of them have a positive relationship with the contribution to business performance, we can interpret that there exists innovation ambidexterity for the consulting projects even though their size of effect is probably different. In contrast, if one activity has a negative relationship with the contribution to business performance, it tells us that one activity hinders another activity. Thus, this result can be proved by previous studies dealing with the paradox of innovation ambidexterity. Therefore, the hypotheses can be generated as below.

Hypothesis 8 (H8). Exploration has a positive impact on contribution to business performance.

Hypothesis 9 (H9). Exploitation has a positive impact on contribution to business performance.

3. Research Model and Method

3.1. Research Model Framework

A consulting model, describing the technical relationship between consulting factors and consulting performance, is structurally analogous to the structural equation model (SEM) within the context of partial least square (PLS).

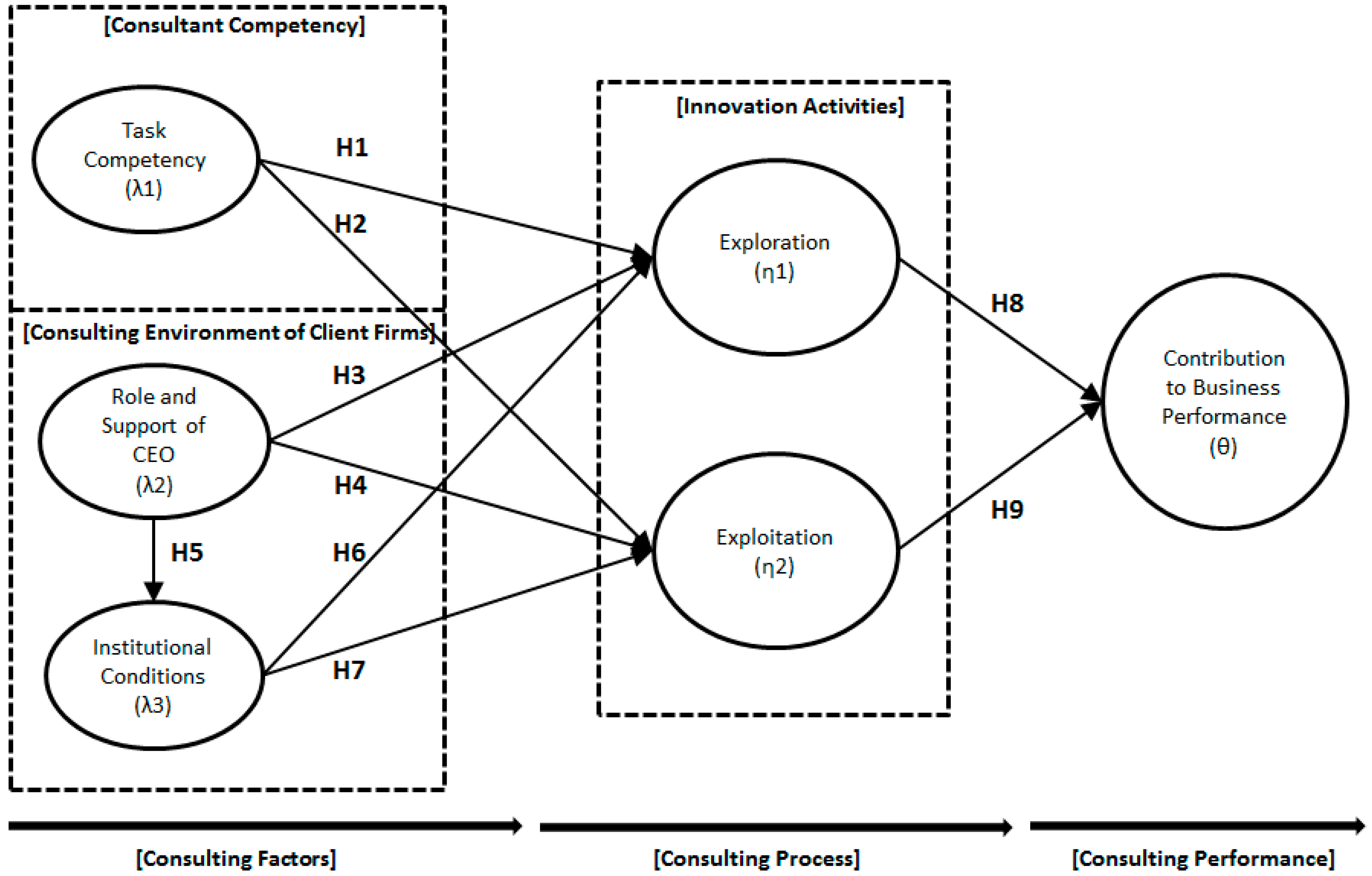

Figure 1 represents a research model framework for consulting and it projects the research hypotheses of this study that already mentioned previous section.

This model framework basically consists of three distinct parts: (1) the part of consulting factors contains three latent variables, task competency of consultants, support of CEOs, and institutional conditions; (2) the part of consulting process represents the system of innovation activities with exploration and exploitation; (3) the part of consulting performance provides the contribution to business performance after the completion of consulting projects. In

Figure 1, each path indicates key hypotheses in this paper. Where

λi is an

i independent variable,

ηi is an

i intervening variable, and

θ is a dependent variable. The major criterion for selecting the consulting inputs and output is based on the previous studies described in the Literature Review and Hypotheses section. These previous studies utilize various latent variables related with consulting models, so in this study, we adopt above five latent variables for our consulting model by preliminary tests with respect to the statistical criteria.

3.2. Data Description

The cross-section data describing both consulting inputs and output were conducted by a survey of 200 samples across several different industry sectors such as knowledge service (18.5%), information technology and service (16.5%), machinery (15.5%), electronic engineering (13.0%), bio and medical sciences (11.5%), chemistry (5.0%), energy (2.0%), etc. (18.0%), in South Korea for a year 2016.

Of the 200 respondents, the survey consists of 113 males (56.3%) and 87 females (43.5%), and the average age of respondents is 43.2, the lowest age is 20, and the highest age is 71. The list of the consulting types includes financial advisory consulting (26.5%), management consulting (19.0%), human resource consulting (14.0%), marketing consulting (14.0%), strategy consulting (12.5%), IT consulting (12.5%), etc. (1.5%).

Table 1 displays a univariate frequency distribution table for the characteristics of survey sample.

Table 2 represents the characteristics of measurement variables in each latent variable. Generally, in survey-type research, especially in seven-point Likert-type scale, the responses are consisted of 1—strongly disagree, 2—disagree, 3—somewhat disagree, 4—neither agree or disagree, 5—somewhat agree, 6—agree, 7—strongly agree. Moreover, each measurement items are based on the previous studies and associated with research hypotheses as well as research model framework (see

Figure 1).

3.3. Model Specification

The consulting model is configured with inputs and an output, but before testing the empirical model with hypotheses in the later section, there needs to check the statistical validity and reliability. In social science related research, the structural equation models should control not only the intangible or tacit factors, such as abilities, skills, experiences, knowledge, but also consider with psychological aspects, such as personality, achievement, sincerity, and so on.

Table 3 represents the results of validity and reliability test for latent variables in

Figure 1 across the various statistical measurement tools.

First, factor loadings, in which any number that lies between 0 and 1, are the standardized path weights connecting the factors to the latent variables. A criterion for the statistically minimum value is generally greater than 0.5, but in

Table 3, all factor loading is at least 0.801. Second, since all coefficients of Cronbach’s α in

Table 3 are greater than 0.7, it is highly probable that there exists a high internal consistency for the consulting model. Third, for testing validity for models, there are two different types: one is a convergent validity, which is demonstrated by coefficients of average variance extracted (AVE) that are greater than 0.7; another is a discriminant validity, which is demonstrated by a minimum value of the squared root of AVE that is greater than any inter-constructed correlations. As shown in

Table 3, all coefficient of AVE is at least 0.836 and it is identically similar to the results of Cronbach’s α. Third, for testing reliability in the consulting model, in

Table 3, all coefficient of composite reliability is at least 0.903, in which the value is much greater than quality criteria for the minimum value, 0.7.

Table 4 represents results of the discriminant validity test and all coefficient of the square root of the AVE is greater than any value for the inter-constructed correlations. The basic idea and purpose of the discriminant validity test is that the measurement variable should not be related with other latent variables. In

Table 4, the test results indicate that the square root of the AVE values of each latent variable are greater than each off-diagonal values. As a result, the measurement scales can be fulfilled with the valid criteria of the discriminant validity test. Therefore, the overall test results provide that the consulting model may have both appropriate convergent and discriminant validity. So, in the statistical specification, the results indicate that the consulting model has significantly high validity and reliability for testing the research hypotheses in later section.

4. Results

4.1. Results of Hypothesis Testing

Again, the consulting model represents a technical relationship between the consulting factors and consulting performance. The conceptual or structural equation model has already figured out via

Figure 1 and it contains key research hypotheses.

Table 5 shows the results of hypothesis testing, which is known as statistical inference. Through the test results, we can interpret the meaning of path coefficients and its direct and indirect effects on the dependent variable, and explain the key research questions in this paper.

In

Table 5, while most of hypotheses can be accepted, H1 and H3 are rejected by the 5% level of statistical significance. The task competency of consultants for consulting projects tends to have a positive impact on exploitation in the consulting client firms, whereas it does not have a statistically significant impact on exploration. Moreover, there is a different magnitude of each path coefficient, so the effect of task competency of consultant on the exploitation is greater than the effect on the exploration in both statistically and numerically. There exist two major interpretations of the rejection problem (H1). First, with regard of the theoretical background on the previous literature, it is highly probable that task competency of consultant is more effective in exploitation than exploration during the consulting projects because task competency implies a deep knowledge of a given area or a specific field. Second, since a dependent variable in the consulting model is the contribution to business performance after the completion of consulting project (denoted as long-term performance), task competency of consultants has a more impact on the business performance through exploitation. Again, since exploitation can be defined as the ability to utilize existing knowledge and resources (include the outcome of consulting projects), it is highly probable that exploitative activities have a greater impact on the contribution to business performance than exploratory activities. However, if the dependent variable were the completion of consulting projects (denoted as short-term performance), the effects of both exploration and exploitation on this kind of a dependent variable are probably similar each other.

In the consulting environment of client firms, basically, we assume that the support of CEOs plays a central role in both their innovation activities and institutional conditions, but the test results show that it does not have a statistical significance with exploration. There are also two main interpretations of this rejection problem (H3). First, in general, CEOs are often interested in short-term results, so they would prefer avoiding risky situations to taking challenges via exploratory activities. Second, in connection with the first interpretation, the support of CEOs may indirectly affect the exploratory activities by strengthening the institutional conditions rather than directly affecting the explorative activities. Thus, this interpretation can be proved by the test result of H5.

Next, the institutional conditions for consulting projects have a positive impact on both exploration and exploitation by 0.1% and 1% levels of statistical significance, respectively. Again, as mentioned earlier, the institutional conditions are highly associated with their system of innovation and its activities. In the magnitude of path coefficients, a relationship degree between institutional conditions and exploration is relatively greater than a relationship degree with exploitation. Thus, it can be interpreted that institutional conditions may have a greater impact on exploratory activities with respect to the ability to seek new knowledge and innovation. Although the effect of the two different types of innovation activities is ostensibly different, they are not only carried out in order to utilize existing knowledge and technology efficiently, but it is also carried out in order to pioneer new market opportunities and to establish business strategies to cope with rapidly changing market environment.

In the results of hypothesis testing, both exploration and exploitation play a significant role in the consulting model. These variables have a positive impact on the contribution to business performance with 1% level of statistical significance. Although the magnitude of both exploration and exploitation are almost similar, exploitation has a relatively more impact on the contribution to business performance because of inherent characteristics of exploitation which are defined as continuity with existing solutions, improvement via refinement, and knowledge utilization within an established framework.

4.2. Effect of Path Coefficients

In the partial least squared (PLS) algorithm of this model, latent variables are normalized to have a mean of 0 and a variance of 1 with a path weighting scheme. Both outer model (measurement) and inner model (structural) path coefficients can be varied from 0 to ±1. In the absolute value of any rational number of path coefficient between 0 and 1, the closest to 1 is the strongest impact on the indicator variables. As shown in

Table 5, the value of each path coefficient has somewhat meaningful explanations of unknown relationships among latent variables in the structural equation model [

62,

63].

First, the rule of path coefficients is used to estimate direct and indirect effects. In

Table 5, all input variable, such as task competency of consultant, support of CEOs, and institutional conditions, have a direct effect on two different types of innovation activities (exploration and exploitation), but not have on a contribution to business performance variable. Second, the indirect effect is the estimation of the path coefficient from one path to another path or multilateral path. Finally, the total effect is the sum of all possible direct and indirect effects. Thus, the detail schemes of direct, indirect, and total effects of this model (see still in

Figure 1 and

Table 5) is below:

Task competency of Consultant: ceteris paribus, a direct effect on both exploration (λ1→η1) and exploitation (λ1→η2) can be calculated by each path coefficient itself, 0.197 and 0.304, respectively, but there is no direct effect on contribution to business performance. In the indirect effect on contribution to business performance, there are two ways to reach the dependent variable, contribution to business performance: one is an exploration path, the product of the path coefficient for λ1→η1 = 0.197 times the path coefficient for η1→θ = 0.283, so the indirect effect is λ1→η1→θ = 0.197 × 0.283 = 0.056; another is an exploitation path and similarly, the indirect effect is λ1→η2→θ = 0.304 × 0.303 = 0.092. By definition, the total effect on contribution to business performance is the sum of exploration and exploitation paths, 0.056 + 0.092 = 0.148.

Support of CEOs: ceteris paribus, a direct effect on both exploration (λ2→η1) and exploitation (λ2→η2) is 0.199 and 0.293, respectively. A direct effect on institutional conditions (λ2→λ3) is 0.560. The indirect effect on contribution to business performance in this case is a little bit complex, but there are four ways to reach the dependent variable: (a) exploration path (λ2→η1→θ = 0.199 × 0.283 = 0.056), (b) exploitation path (λ2→η2→θ = 0.293 × 0.303 = 0.089), (c) institutional conditions-exploration path (λ2→λ3→η1→θ = 0.560 × 0.385 × 0.283 = 0.061), and (d) institutional conditions-exploitation path (λ2→λ3→η2→θ = 0.560 × 0.237 × 0.303 = 0.040). The total effect on contribution to business performance is 0.056 + 0.089 + 0.061 + 0.040 = 0.246.

Institutional conditions: ceteris paribus, a direct effect on both exploration (λ3→η1) and exploitation (λ3→η2) is 0.385 and 0.237, respectively. The indirect effect on contribution to business performance ceteris paribus, is an exploration path (λ3→η1→θ = 0.385 × 0.283 = 0.109) and an exploitation path (λ3→η2→θ = 0.237 × 0.303 = 0.072). The total effect on contribution to business performance is 0.109 + 0.072 = 0.181.

Innovation activities: ceteris paribus, a direct (total) effect of exploration and exploitation on contribution to business performance is their path coefficients themselves, 0.283 and 0.303, respectively.

In the indirect effect on the dependent variable, the contribution to business performance, the institutional conditions with an exploration path (0.109) have a higher impact than all other input variables. Similarly, the task competency of consultant with an exploitation path (0.092) is the second highest and the support of CEOs with an exploitation path (0.089) is the third highest. In the total effect on the contribution to business performance, except exploration and exploitation, the consulting environment of client firms, especially the support of CEOs (0.246), is relatively more important than the consultant competency (0.148) for the contribution to business performance.

It is highly probable that the task competency of consultants is a relatively more standardized factor in the consulting model, whereas the consulting environment of client firms is more likely to have heterogeneous characteristics across the different companies. Thus, the consulting environment of client firms, again, especially the support of CEOs, not only can increase the capability of consultant's task for consulting project, but their institutional conditions. These sophisticated relationships, in which we cannot see or codify, are reflected by the innovation activities and make it possible to improve the business performance.

4.3. Importance and Performance Map Analysis

In this paper, we adopt five major latent variables, except a dependent variable, but there is little information about determination of the relative importance and performance of latent variables in the consulting model [

62,

63].

Table 6 presents the result for latent variable (LV) index values, in which the values are extracted from the PLS algorithm in SmartPLS software package, (importance) and for total effects on the dependent variable (performance). Most of LV index values (again, importance) are similar to each other around 4.5~5.0, but the support of CEOs (5.002) has the highest importance among latent variables and the task competency of consultants (4.976) as well.

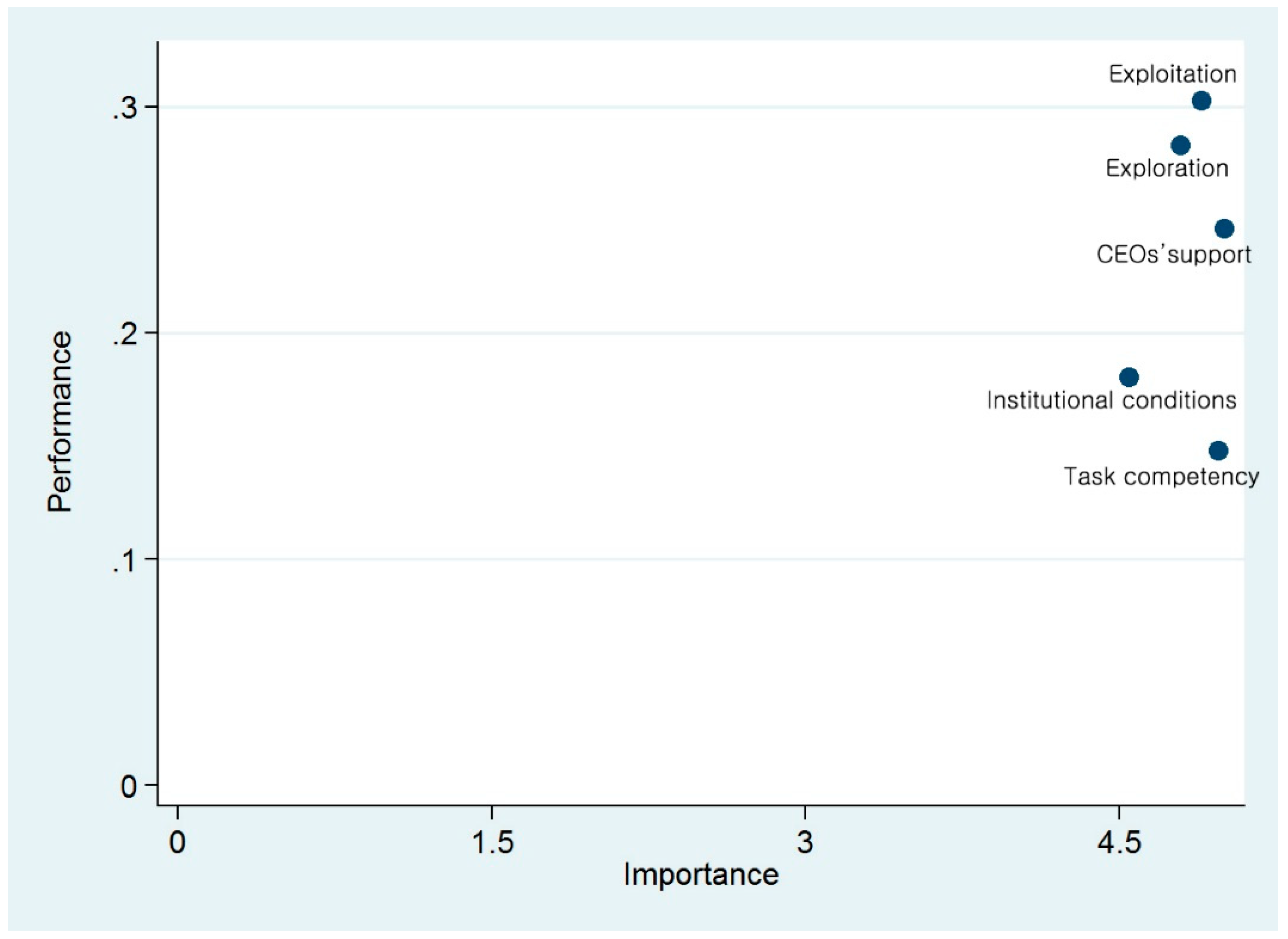

On the other hand, the complicated relationship between importance and performance can be treated by importance-performance map analysis (IPMA).

Figure 2 illustrates IPMA of the dependent variable, contribution to business performance. Both proxy variables, exploration and exploitation, of innovation activities in client firms are primary importance and performance for establishing business performance after consulting projects, especially exploitation. Clearly, the results of IPMA can be classified into two performance groups: a group of high-performance (exploration, exploitation, and CEOs’ support) and a group of low-performance (institutional conditions and task competency of consultant). Again, bear in mind, the level of importance of each latent variable is similar (see in

Table 6).

Although the task competency of consultants’ works is very high on the importance side, its performance for contribution to business performance in client firms is not high enough, relatively speaking. If a dependent variable is about the consulting projects, the task competency of consultants plays a highly significant role in that performance crucially and directly, but the contribution to business performance as a dependent variable has somewhat different stories. Again, within the performance side for the dependent variable in this model, consulting environments of client firms has a greater impact than the consultant competency because the evaluation of business performance after consulting projects depends directly upon the capability of client firms, such as their innovation system and support of CEOs.

5. Discussion

In the rapid changing market environment and information technology, the sustainable business development has become one of the important issues to the researchers, industrial stakeholder and even policy makers. However, in the previous studies of business strategies for firms’ sustainable growth, there have been many ideas and suggestions, but most of them were not related with the business consulting which is known as the most effective way to help firms’ business performance and their sustainable growth. Based on the empirical test results of this paper, we propose some strategies for sustainable business development with regard to the business consulting. First, the CEOs’ support and their decision making for consulting projects are highly important for both the completion of consulting projects and the improvement of their business performance. The successful consulting projects and improved business performance can serve as an engine to reach their sustainable business development. Following the total effect of CEOs’ support for consulting projects on the contribution to business performance, ceteris paribus, CEOs’ support goes up by one unit of Likert scale, on average, the contribution to business performance goes up by about 0.246 Likert scale. Moreover, the test result of IPMA tells us that CEOs’ support for consulting projects has the highest index value, which is an indicator for evaluating the rate of importance among other latent variables in the model.

Second, in order to make sustainable business development, firms’ innovation activities are also significantly important as much important as CEO’s support for consulting projects. Exploration and exploitation are denoted by the proxy variables for firms’ innovation activities. These proxies are also known as variables for innovation ambidexterity. The firms’ innovation activities via business consulting can increase their ability to utilize and absorb the external resources and knowledge. These abilities are used not only to induce their business innovation internally but also an outlet to pioneer new markets amid a rapidly changing market environment. According to the empirical test results in this paper, both exploration and exploitation have the highest impacts on the contribution to business performance, Moreover, the indirect effects of task competency of consultant via exploitation on the contribution to business performance are also higher than the effects of other latent variables. The results of IPMA indicate that in the combination between importance and performance indices, exploitation and exploration are the first and second place, respectively (see detail in

Figure 2). However, in the result of hypothesis testing, the relationship between task competency of consultants and exploration does not have a statistical significance and it is rejected by 5% level. As mentioned in the Results section, the relationship can be affected by two characteristics: one is that consultants are likely to favor exploitative activities because their task competency usually implies a deep knowledge of a given area; another is that the dependent variable, the contribution to business performance, relies more on exploitative activities in the long-term perspective.

Third, the CEOs’ competency for recognizing the awareness of newly changing market conditions and the importance of utilizing business consulting is the most important factor to make strategies for their sustainable business development. By the same token, it is highly probable that the business consulting can improve firms’ innovation system and its activities for utilizing and detecting external resources and knowledge. Therefore, within the context of importance of business consulting, focusing on increasing the support of CEOs for consulting projects and enhancing innovation activities via exploration and exploitation are meaningful for establishing strategies for sustainable business development. Nevertheless, the test result indicates that there is statistically no significance between the support of CEOs and exploration. Since CEOs are often interested in short-run outcomes, they are likely to favor risk-avoiding situations via exploitative activities. Instead, the support of CEOs can affect exploratory activities indirectly via the institutional conditions. Considering the characteristics of CEOs and their supports not only makes it possible to carry out efficient consulting projects but also to establish strategies for sustainable business development.

6. Conclusions

This study has explored the strategies for sustainable business development via the process and performance of business consulting by using 200 samples of different industry sectors in South Korea. We have built upon the consulting model framework with taking into account the relationship between consulting factors and consulting performance. The empirical test results show meaningful and intuitive research outcomes. Almost all of consulting factors have a positive relationship with the two different types of innovation activities, exploration and exploitation, and the contribution to business performance. The test results are as follows. First, we found that while the task competency of consultants has a statistical positive impact on exploitation, the relationship between task competency of consultants and exploration is not statistically significant and the hypothesis is rejected by 5% level of significance. The result can be explained by two interpretations: one is that consultants are likely to favor exploitative activities because their task competency usually implies a deep knowledge of a given area; another is that the dependent variable, the contribution to business performance, relies more on exploitative activities in the long-term perspective. Second, in the consulting environment of client firms, the test result indicates that the support of CEOs for consulting only affects exploitation, but not exploration. Since CEOs are often interested in short-run outcomes, they are likely to favor risk-avoiding situations via exploitative activities. However, institutional conditions for consulting have a positive significant impact on both exploration and exploitation. Although the test results do not support the relationship between the support of CEOs and exploration statistically and directly, it affects exploratory activities indirectly via institutional conditions. Finally, the two different types of innovation activities, exploration and exploitation, have a statistically positive impact on the contribution to business performance.

Within the context of indirect effects, the institutional conditions via an exploration path has the highest impact on the contribution to business performance. Moreover, both the task competency of consultant and the CEOs’ support via an exploitation path have almost similar impacts on the contribution to business performance. In the total effects, clearly the firms’ innovation activities with exploitation have the highest impact and with exploration have the second highest impact on the contribution to business performance, but in the consulting factors, the support of CEO has a higher impact on the contribution to business performance than other consulting factors. In the importance-performance map analysis (IPMA), this analysis provides insightful interpretations of the consulting factors. As mentioned before, in the indirect effects on the contribution to business performance, the institutional conditions and the task competency of consultant have relatively higher impacts than other latent variables, but the results from IPMA are somewhat different. These latent variables are placed in a group of high-importance, but not in a group of high-performance. However, the support of CEOs and the innovation activities, exploration and exploitation (and ambidexterity), are placed in both a group of high importance and performance in the model. Thus, the support of CEOs and innovation activities, exploration and exploitation (and ambidexterity), play a central role in the consulting model.

These results can be useful for understanding the implications for the strategies with respect to the sustainable business development. The sustainable business development has become one of the important issues amid a rapid changing market environment and information technology. The test results in this paper provide some meaningful implications. First, the support of CEOs for consulting projects can increase not only their innovation activities but also their business performance. This kind of CEOs’ support can be associated with the competency for recognizing the awareness of newly changing market conditions and the importance of utilizing business consulting. These factors can serve as an engine to reach their sustainable business development. Moreover, considering the characteristics of CEOs and their supports not only makes it possible to carry out efficient consulting projects but also to establish strategies for sustainable business development. Second, the firms’ innovation activities, exploration, exploitation (and ambidexterity), via business consulting can increase their ability to utilize and absorb the external resources and knowledge. These abilities are used not only to induce their business innovation internally but also to pioneer new market opportunities amid a rapidly changing market environment. Therefore, focusing on the importance of the support of CEOs for consulting projects and enhancing the firm’s innovation activities (balancing between exploration and exploitation) can play an important role in establishing strategies for sustainable business development.

Despite interesting preliminary findings, there are at least three major shortcomings in our approaches. First, which we hope to address in further studies, the consulting model should take into account the relationships between the contribution to business performance and the completion of consulting projects. We expect that the relationships can be treated by the system of equations or the sequential effect. Second, since the range of consultant competency in the study is quite simple (adopted only a single latent variable), we will add more latent variables like management competency and commitment of consultants, in further studies. Third, in this study, we used various types of industries, but not take its heterogeneous and specific characteristics into account in the model in order to prevent the loss of generality. Therefore, in further study, we will consider the industry-specific characteristics through using a group analysis.

Furthermore, this study provides some meaningful suggestions for further studies related with the business consulting and its model framework. First, the role of CEOs or board of directors and their decision making processes should be considered in depth when establishing a consulting model, especially for SMEs. Second, with regard to the model analysis, it is highly important to utilize the interpretation of path coefficients, which can show not only the details and implicit meanings from the test results, but also the evaluation of the impact size of each consulting factor.