A Scale Development of Retailer Equity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

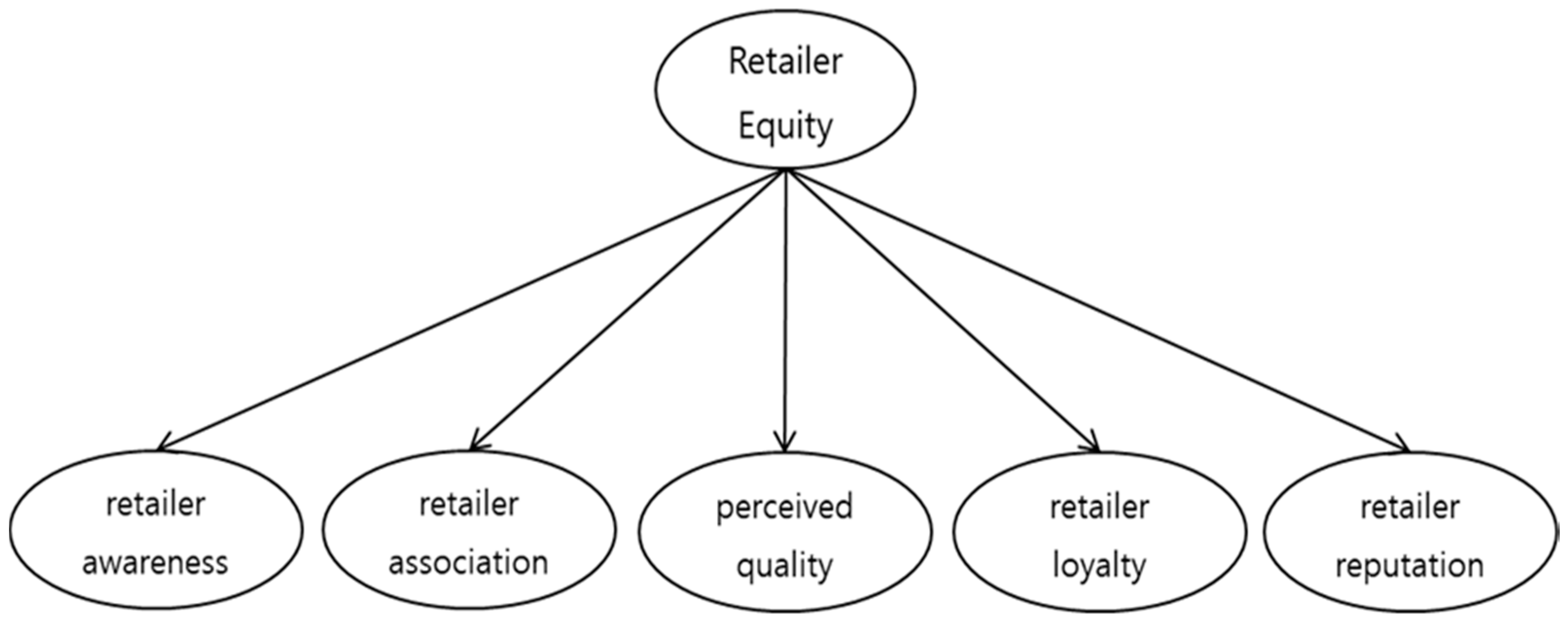

2.1. Retailer Equity

2.2. Conceptualization of Scale of Multi-Dimensional Retailer Equity

2.2.1. Retailer Awareness

2.2.2. Retailer Associations

2.2.3. Perceived Retailer Quality

2.3.4. Retailer Loyalty

2.3.5. Retailer Reputation

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Measures

3.2. Scale Development Procedure

3.2.1. Literature Search and Experience Survey

3.2.2. Exploratory and Formal Pretests

3.2.3. Field Study

4. Results

4.1. Construct Validation of Retailer Equity

4.2. Discriminant Validity of Retailer Equity

4.3. Nomological Validation of Retailer Equity

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications and Significance

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Items | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Retailer awareness | Some characteristics (symbol or logo) of X retail store come to my mind quickly. I am aware of X retail store. I can recognize this X retail store among other competing stores. | Arnett et al. (2003) Pappu and Quester (2006) Anselmsson et al. (2017) Londoño et al. (2017) El Hedhli and Chebat (2009) |

| Retailer associations | X retail store offers very good store atmosphere. X retail store offer very convenient facilities. X retail store offer very good customer service. X retail store offer very good variety of products. Merchandise at X retail store is a very good value. | Pappu and Quester (2006) Choi and Huddleston (2014) |

| Perceived retailer quality | X retail store provides excellent service to its customers. Overall, X retail store sells high quality merchandise. X retail store offers very reliable products. X retail store offers good deals relative to other offers available in the market There is a high likelihood that items bought at X retail store will be of extremely high quality. | Arnett et al. (2003) Pappu and Quester (2006) Anselmsson et al. (2017) Londoño et al. (2017) El Hedhli and Chebat (2009) Choi and Huddleston (2014) |

| Retailer loyalty | I consider myself to be loyal to X retail store. When buying some items, X retail store is my first choice. I would recommend X retail store to others | Arnett et al. (2003) Pappu and Quester (2006) Anselmsson et al. (2017) Londoño et al. (2017) Choi and Huddleston (2014) |

| Retailer reputation | I admire and respect the X retail store. I have total confidence in this X retail store. I trust the X retail store. X retail store has a clear vision for its future. X retail store is the most popular retailer in the category | Anselmsson et al. (2017) Ou et al. (2006) |

References

- Sirohi, N.; McLaughlin, E.W.; Wittink, D.R. A model of consumer perceptions and store loyalty intentions for a supermarket retailer. J. Retail. 1998, 74, 223–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloemer, J.M.M.; Odekerken-Schröder, G.J. Store satisfaction and store loyalty explained by customer-and store related factors. J. Consum. Satisf. Dissatisfaction Complain. Behav. 2002, 15, 68–80. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, P. An empirical study on the influence of store image on relationship quality and retailer brand equity. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on Future Information Technology and Management Engineering (FITME), Changzhou, China, 9–10 October 2010; Volume 2, pp. 146–149. [Google Scholar]

- Feuer, J. Retailing grows up, looks to image-building. Adweek 2005, 16, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Pappu, R.; Quester, P.G. Does brand equity vary between department stores and clothing stores? Results of an empirical investigation. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2008, 17, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, D.B.; Laverie, D.A.; Meiers, A. Developing parsimonious retailer equity indexes using partial least squares analysis: A method and applications. J. Retail. 2003, 79, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Brand equity management in a multichannel, multimedia retail environment. J. Interact. Mark. 2010, 24, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, G.; Datta, B.; Guin, K.K. From brands in general to retail brands: A review and future agenda for brand personality measurement. Mark. Rev. 2012, 12, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swoboda, B.; Berg, B.; Schramm-Klein, H.; Foscht, T. The importance of retail brand equity and store accessibility for store loyalty in local competition. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2013, 20, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Londoño, J.C.; Elms, J.; Davies, K. Conceptualising and measuring consumer-based brand–retailer–channel equity. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 29, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselmsson, J.; Burt, S.; Tunca, B. An integrated retailer image and brand equity framework: Re-examining, extending, and restructuring retailer brand equity. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 38, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, D.; Levy, M.; Lehmann, D.R. Retail branding and customer loyalty: An overview. J. Retail. 2004, 4, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ailawadi, K.L.; Keller, K.L. Understanding retail branding: Conceptual insights and research priorities. J. Retail. 2004, 80, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappu, R.; Quester, P. A consumer-based method for retailer equity measurement: Results of an empirical study. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2006, 13, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A. Managing Brand Equity; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991; ISBN 0-02-900101-3. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman, K.B.; Spiro, R.L. Recapturing store image in customer-based store equity: A construct conceptualization. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 1112–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinfeng, W.; Zhilong, T. The impact of selected store image dimensions on retailer equity: Evidence from 10 Chinese hypermarkets. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2009, 16, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L.; Lehmann, D.R. How do brands create value? Mark. Manag. 2003, 12, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Saura, I.; Ruiz-Molina, M.E.; Michel, G.; Corraliza-Zapata, A. Retail brand equity: A model based on its dimensions and effects. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2013, 23, 111–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, G. Impact of store attributes on consumer-based retailer equity: An exploratory study of department retail stores. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2015, 19, 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swoboda, B.; Weindel, J.; Hälsig, F. Predictors and effects of retail brand equity—A cross-sectoral analysis. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 31, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, B.; Donthu, N. Developing and validating a multidimensional consumer-based brand equity scale. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 52, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElHedhli, K.; Chebat, J.C. Developing and validating a psychometric shopper-based mall equity measure. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, W.B.; Monroe, K.B.; Grewal, D. Effects of price, brand, and store information on buyers’ product evaluations. J. Mark. Res. 1991, 28, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, D.; Krishnan, R.; Baker, J.; Borin, N. The effect of store name, brand name and price discounts on consumers’ evaluations and purchase intentions. J. Retail. 1998, 74, 331–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebat, J.C.; El Hedhli, K.; Sirgy, M.J. How does shopper-based mall equity generate mall loyalty? A conceptual model and empirical evidence. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2009, 16, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thang, D.C.L.; Tan, B.L.B. Linking consumer perception to preference of retail stores: An empirical assessment of the multi-attributes of store image. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2003, 10, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P. Marketing Management: Analysis, Planning, Implementation, and Control; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1997; ISBN 0132613638. [Google Scholar]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A. The behavioral consequences of service quality. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, G. Linkages of retailer personality, perceived quality and purchase intention with retailer loyalty: A study of Indian non-food retailing. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2014, 21, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, B.J.; Attaway, J.S. Atmospheric affect as a tool for creating value and gaining share of customer. J. Bus. Res. 2000, 49, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, J.; Chestnut, R.W. Brand Loyalty: Measurement and Management; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1978; ISBN 0471028452. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, C.; Sparks, L. Loyalty saturation in retailing: Exploring the end of retail loyalty cards? Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 1999, 27, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, D.W.; Giese, J.L.; Johnson, J.L. Customer retailer loyalty in the context of multiple channel strategies. J. Retail. 2004, 80, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmer, J.M.T. Corporate Identity: Past, Present and Future; Working Paper Series; University of Strathclyde: Glasgow, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Balmer, J.M.T. Corporate identity, corporate branding and corporate marketing: Seeing through the fog. Eur. J. Mark. 2001, 35, 248–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.; Leblanc, G. Corporate image and corporate reputation in customers’ retention decisions in services. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2001, 8, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotsi, M.; Wilson, A. Corporate reputation: Seeking a definition. Corp. Commun. 2001, 6, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C.J. Reputation; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Burt, S.; Carralero-Encinas, J. The role of store image in retail internationalisation. Int. Mark. Rev. 2000, 17, 433–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmer, J.M.T.; Wilson, A. Corporate identity: There is more to it than meets the eye. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 1998, 28, 12–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, W.-M.; Abratt, R.; Dion, R. The influence of retailer reputation on store patronage. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2006, 13, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C.J.; Van Riel, C.B. The reputational landscape. Corp. Reput. Rev. 1997, 1, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, L.; Huddleston, P. The effect of retailer private brands on consumer-based retailer equity: Comparison of named private brands and generic private brands. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2014, 24, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, G.A. A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbing, D.W.; Anderson, J.C. An updated paradigm for scale development incorporating unidimensionality and its assessment. J. Mark. Res. 1988, 25, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Some methods for respecifying measurement models to obtain unidimensional construct measurement. J. Mark. Res. 1982, 19, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappu, R.; Quester, P. A commentary on “conceptualizing and measuring Consumer-Based Brand-Retailer-Channel Equity”. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 37, 31–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarjana, S.; Kartini, D.; Rufaidah, P. Reputation development strategy for corporate operating in industrial estate. Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, D.S.; Kuo, M.J. A study on the customer-based brand equity of online retailers. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE/ACIS 9th International Conference on Computer and Information Science (ICIS), Yamagata, Japan, 18–20 August 2010; pp. 295–300. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, X.; Su, R. Drivers and dimensions of web equity for B2C retailers. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on E-Business and E-Government (ICEE), Shanghai, China, 6–8 May 2011; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | α | AVE | CR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived retailer quality | 1 | 0.788 | 0.919 | 0.614 | 0.888 | ||||

| 2 | 0.783 | ||||||||

| 3 | 0.809 | ||||||||

| 4 | 0.797 | ||||||||

| 5 | 0.741 | ||||||||

| Retailer associations | 1 | 0.837 | 0.964 | 0.735 | 0.932 | ||||

| 2 | 0.867 | ||||||||

| 3 | 0.873 | ||||||||

| 4 | 0.873 | ||||||||

| 5 | 0.838 | ||||||||

| Retailer reputation | 1 | 0.769 | 0.949 | 0.582 | 0.762 | ||||

| 2 | 0.786 | ||||||||

| 3 | 0.780 | ||||||||

| 4 | 0.750 | ||||||||

| 5 | 0.728 | ||||||||

| Retailer awareness | 1 | 0.758 | 0.889 | 0.631 | 0.794 | ||||

| 2 | 0.838 | ||||||||

| 3 | 0.786 | ||||||||

| Retailer loyalty | 1 | 0.757 | 0.898 | 0.636 | 0.797 | ||||

| 2 | 0.816 | ||||||||

| 3 | 0.819 | ||||||||

| Eigenvalue | 11.410 | 2.173 | 1.647 | 1.110 | 1.035 | ||||

| Varience (%) | 54.332 | 10.347 | 7.845 | 5.285 | 4.928 | ||||

| Fit statistics | |||||||||

| Chi-square with 179 degrees of freedom | 437.916 (p < 0.001) | ||||||||

| Goodness-of fit index | 0.898 | ||||||||

| Adjusted goodness-of-fit index | 0.868 | ||||||||

| Comparative fit index | 0.967 | ||||||||

| Normed fit index | 0.945 | ||||||||

| Relative fit index | 0.936 | ||||||||

| Incremental fit index | 0.967 | ||||||||

| Tucker-Lewis index | 0.961 | ||||||||

| Root mean square residual | 0.038 | ||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retailer awareness | 0.794 ** | ||||

| Retailer associations | 0.421 * | 0.857 ** | |||

| Perceived retailer quality | 0.515 * | 0.567 * | 0.783 ** | ||

| Retailer loyalty | 0.598 * | 0.469 * | 0.524 * | 0.797 ** | |

| Retailer reputation | 0.639 * | 0.618 * | 0.615 * | 0.639 * | 0.762 ** |

| Independent Variables | Dependent Variables | |

|---|---|---|

| Usage Intention | ||

| Standardized Beta | t-Value | |

| Retailer awareness | 0.258 | 5.940 (p < 0.001) |

| Retailer associations | 0.089 | 2.130 (p = 0.034) |

| Perceived retailer quality | 0.140 | 3.276 (p = 0.01) |

| Retailer loyalty | 0.278 | 6.389 (p < 0.001) |

| Retailer reputation | 0.211 | 4.154 (p < 0.001) |

| R-square | 0.640 | |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, S.H.; Lee, S.-H. A Scale Development of Retailer Equity. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3924. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10113924

Lee SH, Lee S-H. A Scale Development of Retailer Equity. Sustainability. 2018; 10(11):3924. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10113924

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Seong Ho, and Sun-Ho Lee. 2018. "A Scale Development of Retailer Equity" Sustainability 10, no. 11: 3924. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10113924

APA StyleLee, S. H., & Lee, S.-H. (2018). A Scale Development of Retailer Equity. Sustainability, 10(11), 3924. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10113924