The Investigation of Consumers’ Behavior Intention in Using Green Skincare Products: A Pro-Environmental Behavior Model Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Can the PERA model be applied to analyzing the female Indonesian customers’ intention to purchase green skincare products?

- What are the factors and key factors that influence the female Indonesian customers’ intention to purchase green skincare products?

- What managerial recommendations can be provided to increase female Indonesian customers’ intention to purchase green skincare products?

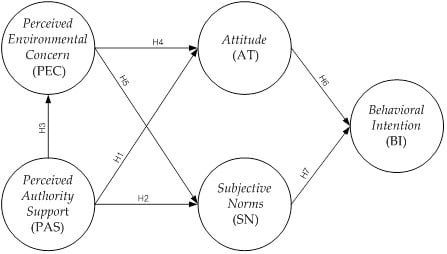

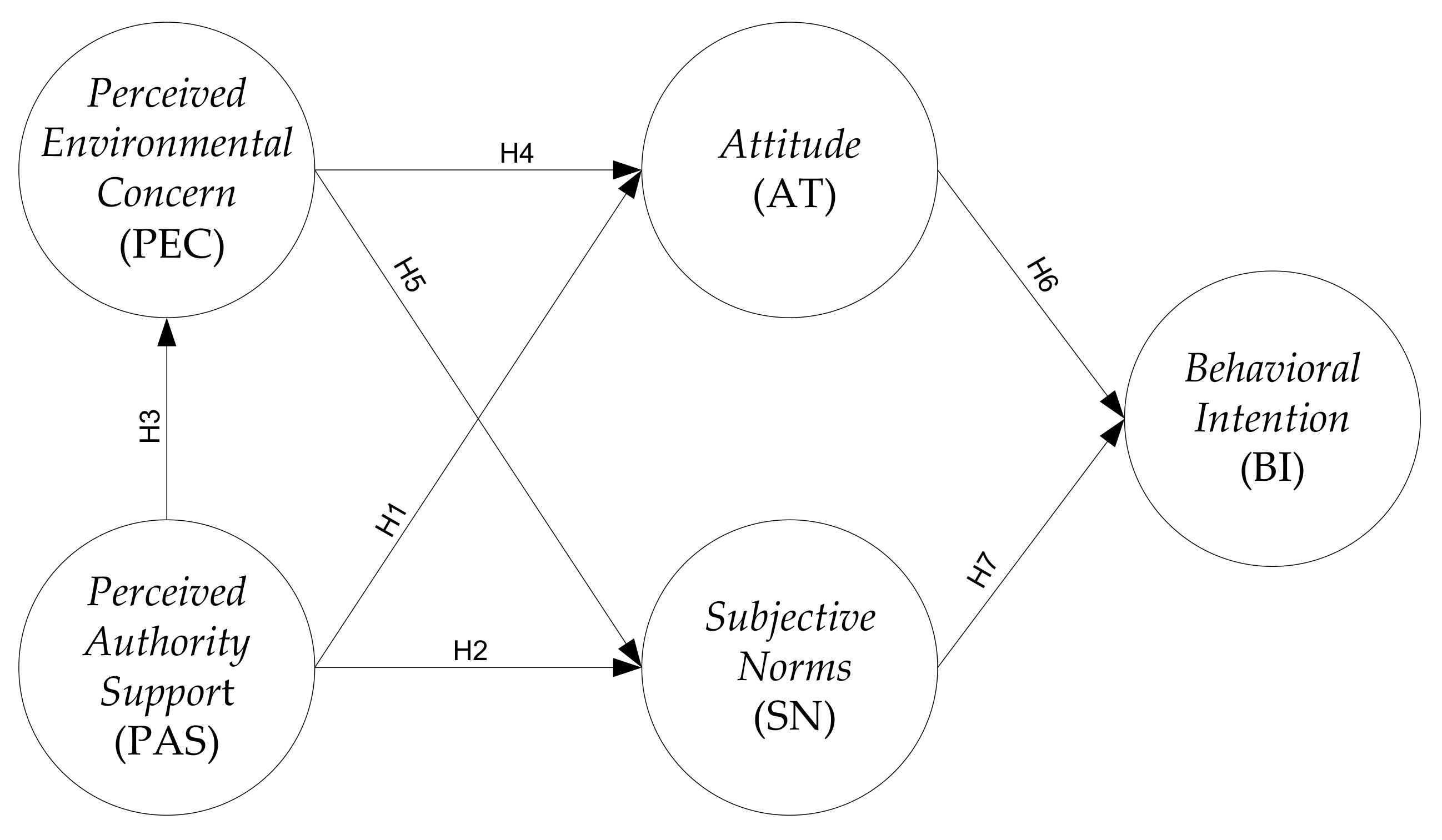

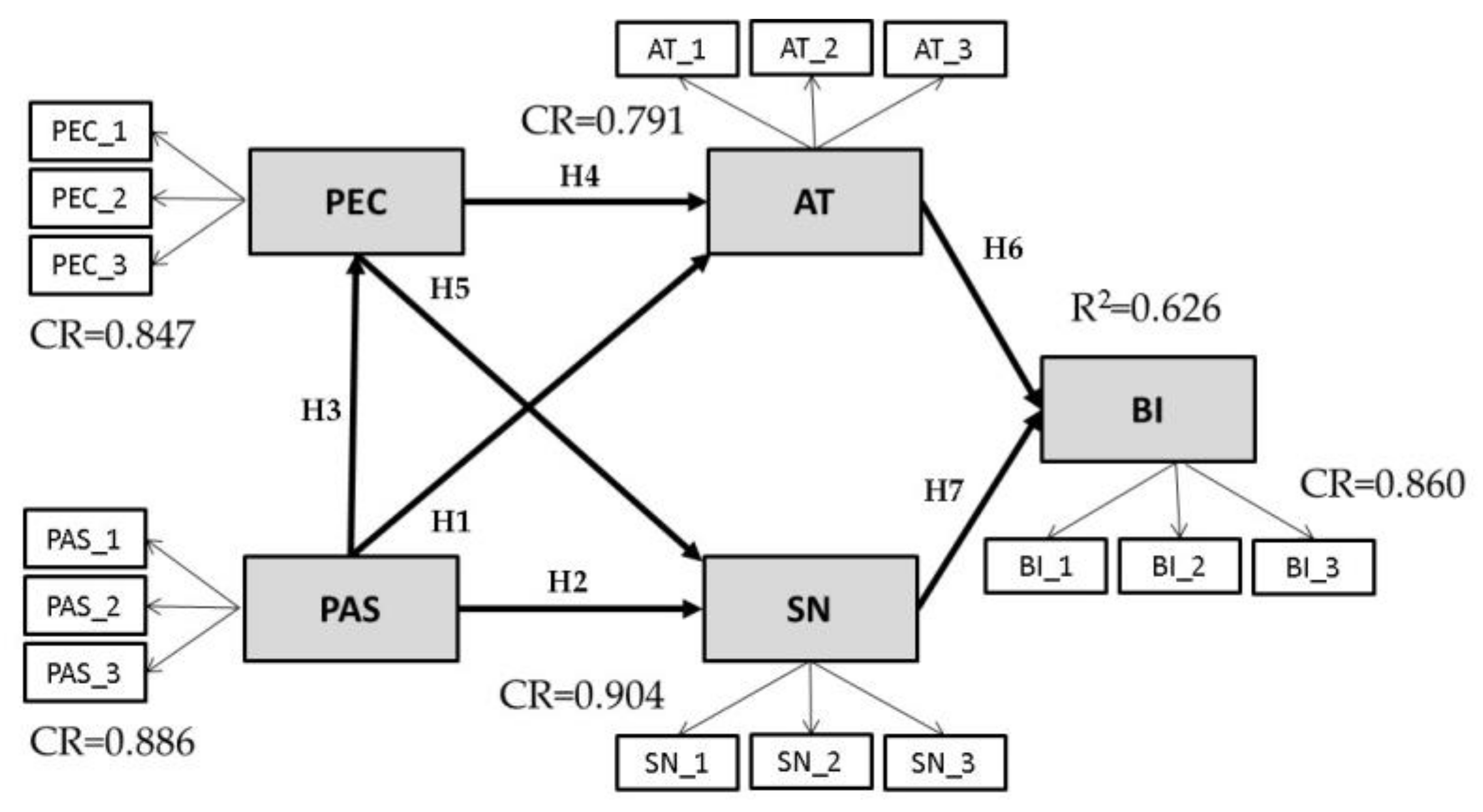

2. Hypothesis Development and Research Model

2.1. Description of Green Cosmetics and Green Skincare

2.2. Theory of Reasoned Action and Pro-Environmental Reasoned Action

2.3. Methodology

2.3.1. Participants and Procedure

2.3.2. Measures of the Construct

2.3.3. Statistical Analysis

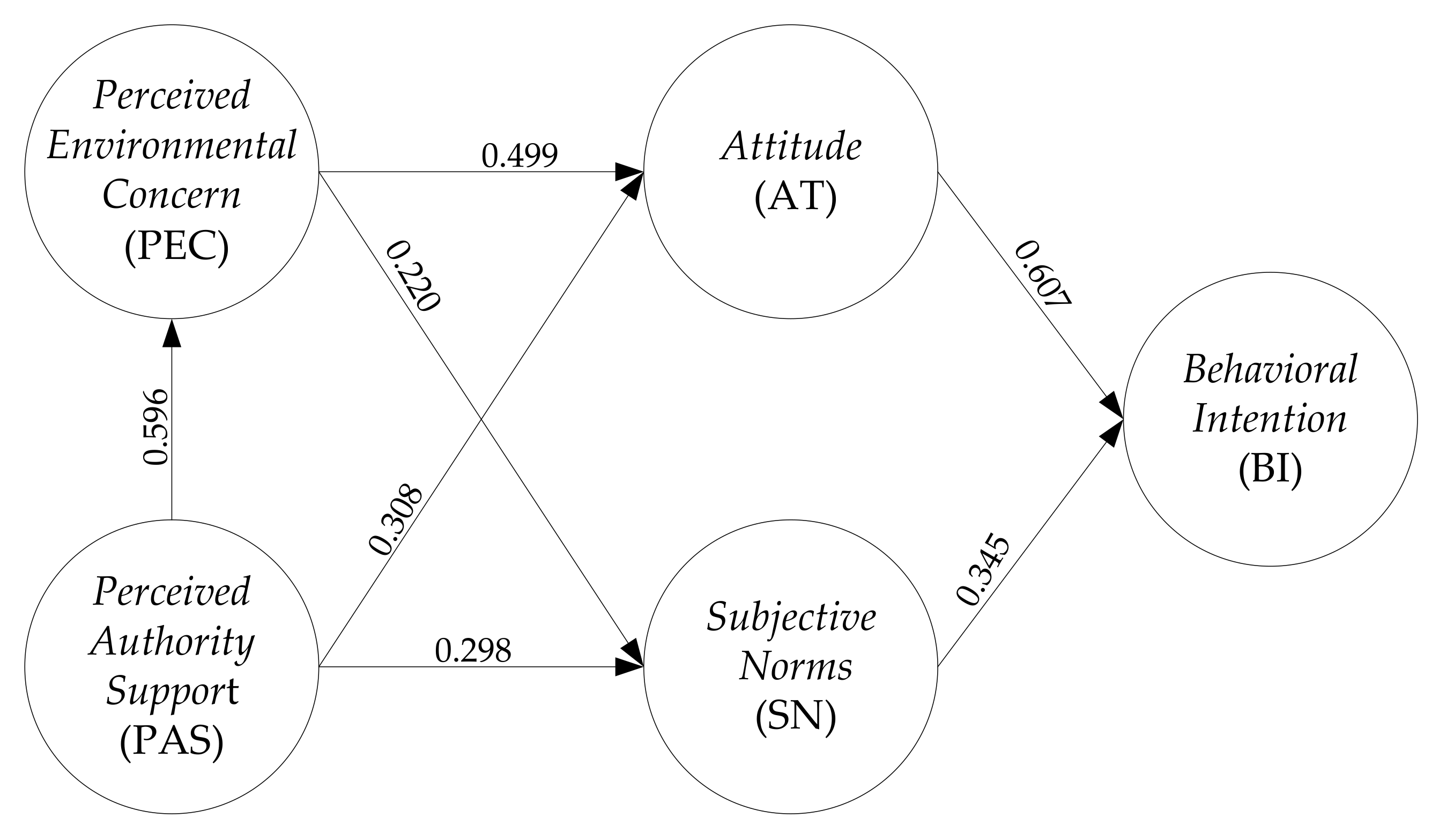

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Statistical Interpretation

4.2. Managerial Interpretation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Delafrooz, N.; Taleghani, M.; Nouri, B. Effect of green marketing on consumer purchase behavior. QSci. Connect 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Harun, A.; Sulong, R.S.; Lily, J. The influence of consumers’ perception of green products on green purchase intention. Int. J. Asian Soc. Sci. 2014, 4, 924–939. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen. Looking to Achieve New Product Sucess. Nielsen Global New Product Innovation Report June 2015; Nielsen: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C.-L.; Chang, C.-Y.; Yansritakul, C. Exploring purchase intention of green skincare products using the theory of planned behavior: Testing the moderating effects of country of origin and price sensitivity. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 34, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluczek, A. Quick green scan: A methodology for improving green performance in terms of manufacturing processes. Sustainability 2017, 9, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, M.; Darnton, G. Green companies or green con-panies: Are companies really green, or are they pretending to be? Bus. Soc. Rev. 2005, 110, 117–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Modi, A.; Patel, J. Predicting green product consumption using theory of planned behavior and reasoned action. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottman, J.A. Green Marketing; NTC Business Book: Chicago, IL, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cheong, S.-K.; Coulthart, J.; Kanawati, J.; Han, A.; Li, J.; Maryarini, P.; Ono, C.; Pookan, M.; Robles, D.; Rumeral, Y.; et al. Asia Personal Care & Cosmetic Market Guide; U.S. Department of Commerce: Washington, DC, USA, 2016.

- Ribeiro, A.S.; Estanqueiro, M.; Oliveira, M.B.; Sousa Lobo, J.M. Main benefits and applicability of plant extracts in skin care products. Cosmetics 2015, 2, 48–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Bergeron, J.; Barbaro-Forleo, G. Targeting consumers who are willing to pay more for environmentally friendly products. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pudaruth, S.; Juwaheer, T.D.; Seewoo, Y.D. Gender-based differences in understanding the purchasing patterns of eco-friendly cosmetics and beauty care products in mauritius: A study of female customers. Soc. Responsib. J. 2015, 11, 179–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basumbul, A.N. Consumer’s Attitude in Mediating the Influence of Green Marketing on the Purchase Intention; University of Lampung: Lampung, Indonesia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, D.; Akman, I.; Mishra, A. Theory of reasoned action application for green information technology acceptance. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 36, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postmus, J.-K. Influence of Corporate Green Reputation on Sustainable Consumer Buying Behaviour; Wageningen UR: Wageningen, Holland, 2017; pp. 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Sukato, N.; Elsey, B. A model of male consumer behaviour in buying skin care products in thailand. ABAC J. 2009, 29, 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, B.K. The Impact of Consumer Innovativeness, Attitude, and Subjective Norm on Cosmetic Buying Behavior: Evidence from Apu Female Students; Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University: Beppu, Japan, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nikdavoodi, J. The Imapct of Attitude, Subjective Norm and Consumer Innovativeness on Cosmetic Buying Behavior; Lund University: Lund, Sweden, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Leow, S.M.Y.S.; Ling, B.H.; Yeo, S.L. Factors Influencing the Awareness and Purchase of “Green” Cosmetics; Nanyang Technologycal University: Singapore, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, T.; Risborg, M.S.; Steen, C.D. Understanding consumer purchase of free-of cosmetics: A value-driven tra approach. J. Consum. Behav. 2012, 11, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askadilla, W.; Krisjanti, M. Understanding indonesian green consumer behavior on cosmetic products: Theory of planned behavior model. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2017, 15, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liobikienė, G.; Bernatonienė, J. Why determinants of green purchase cannot be treated equally? The case of green cosmetics: Literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadlifatin, R.; Lin, S.-C.; Rachmaniati, Y.P.; Persada, S.F.; Razif, M. A pro-environmental reasoned action model for measuring citizens’ intentions regarding ecolabel product usage. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soerjanatamihardja, K.A.; Fachira, I. Study of perception and attitude towards green marketing of indonesian cosmetics consumers. J. Bus. Manag. 2017, 6, 160–172. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca-Santos, B.; Corrêa, M.A.; Chorilli, M. Sustainability, natural and organic cosmetics: Consumer, products, efficacy, toxicological and regulatory considerations. Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 51, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambín, J.-J.P. Marketing Estratégico; McGraw-Hill Interamericana: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ottman, J.A. Green Marketing: Challenges and Opportunities for the New Marketing Age; NTC Business Books: Lincolnwood, IL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Rawat, S.R.; Garga, P.K. Understanding Consumer Behaviour towards Green Cosmetics; SSRN: Rochester, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Penzer, R.; Ersser, S. Principles of Skin Care: A Guide for Nurses and Health Care Practitioners; John Wiley & Sons: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Southey, G. The theories of reasoned action and planned behaviour applied to business decisions: A selective annotated bibliography. J. New Bus. Ideas Trends 2011, 9, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Trafimow, D. The theory of reasoned action: A case study of falsification in psychology. Theory Psychol. 2009, 19, 501–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, J.L.; Householder, B.J.; Greene, K.L. The Theory of Reasoned Action. In The Persuasion Handbook: Developments in Theory and Practice; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 259–286. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, L.J.; Bahnan, N.; Kelkar, M.; Curry, N. Walking the walk: How the theory of reasoned action explains adult and student intentions to go green. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 2011, 27, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelkar, M.; Coleman, L.J.; Bahnan, N.; Manago, S. Green consumption or green confusion. J. Strateg. Innov. Sustain. 2014, 9, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Persada, S.F. Pro Environmental Planned Behavior Model to Explore the Citizens’ Participation Intention in Environmental Impact Assessment: An Evidence Case in Indonesia. Ph.D. Thesis, Industrial Management Department, National Taiwan University of Science and Technology, Taipei, Taiwan, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Biloslavo, R.; Trnavčevič, A. Web sites as tools of communication of a “green” company. Manag. Decis. 2009, 47, 1158–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-C.; Persada, S.F.; Nadlifatin, R.; Tsai, H.-Y.; Chu, C.-H. Exploring the influential factors of manufacturers’ initial intention in applying for the green mark ecolabel in taiwan. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. -Green Technol. 2015, 2, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadlifatin, R.; Razif, M.; Lin, S.-C.; Persada, S.F.; Belgiawan, P.F. An assessment model of indonesian citizens’ intention to participate on environmental impact assessment (EIA): A behavioral perspective. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2015, 28, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persadaa, S.F.; Lina, S.-C.; Nadlifatina, R.; Razifb, M. Investigating the Behavior of Citizens To Use ICT in Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA). In Proceedings of the Third Information System International Conference (ISICO 2015), Surabaya, Indonesia, 2–4 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.-C.; Rachmaniati, Y.P.; Nadlifatin, R.; Razif, M.; Persada, S.F.; Lin, A. Understanding the Consumers’ Perspective in Accepting the Ecolabel Product by a Structural Reasoned Model Assessment. In Proceedings of the 17th Asia Pacific Industrial Engineering and Management System Conference, Taipei, Taiwan, 7–10 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fransson, N.; Gärling, T. Environmental concern: Conceptual definitions, measurement methods, and research findings. J. Environ. Psychol. 1999, 19, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaola, P.; Potiane, B.; Mokhethi, M. Environmental concern, attitude towards green products and green purchase intentions of consumers in lesotho. Ethiop. J. Environ. Stud. Manag. 2014, 7, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranz, J.; Picot, A. Why Are Consumers Going Green? The Role of Environmental Concerns in Private Green-Is Adoption; ECIS: London, UK, 2011; p. 104. [Google Scholar]

- Ming, B.H.; Gan, G.G.G.; Ramasamy, S. The role of concern for the environment and perceived consumer effectiveness on investors’ willingness to invest in environmentally-friendly firms. Kaji. Malays. J. Malays. Stud. 2015, 33, 173–190. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, T.K.; Ab Majid, N.F.N.; Harun, N.H.; Othman, N. Assessing the Variables that Influence the Intention of Green Purchase. In Proceedings of the Social Sciences Research ICSSR, Sabah, Malaysia, 9–10 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persada, S.; Lin, S.; Nadlifatin, R.; Razif, M. Investigating the citizens’ intention level in environmental impact assessment participation through an extended theory of planned behavior model. Glob. NEST J. 2015, 17, 847–857. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.-C.; Nadlifatin, R.; Amna, A.R.; Persada, S.F.; Razif, M. Investigating citizen behavior intention on mandatory and voluntary pro-environmental programs through a pro-environmental planned behavior model. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denscombe, M. The Good Research Guide: For Small-Scale Social Research Projects; McGraw-Hill Education (UK): London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, I.-L.; Wu, K.-W. A hybrid technology acceptance approach for exploring e-CRM adoption in organizations. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2005, 24, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, N. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, J.; Lin, S.-C. Investigating users’ perspectives in building energy management system with an extension of technology acceptance model: A case study in indonesian manufacturing companies. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 72, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, J.; Lin, S.-C. A behavioral model of managerial perspectives regarding technology acceptance in building energy management systems. Sustainability 2016, 8, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turaga, R.M.R.; Howarth, R.B.; Borsuk, M.E. Pro-environmental behavior. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1185, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trafimow, D. Predicting intentions to use a condom from perceptions of normative pressure and confidence in those perceptions. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 24, 2151–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinodkumar, M.; Bhasi, M. Safety climate factors and its relationship with accidents and personal attributes in the chemical industry. Saf. Sci. 2009, 47, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Reliability analysis. In Research Methods II; Sage: London, UK, 2006; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.-C.; Mufidah, I.; Persada, S.F. Safety-culture exploration in taiwan’s metal industries: Identifying the workers’ background influence on safety climate. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ek, Å.; Runefors, M.; Borell, J. Relationships between safety culture aspects—A work process to enable interpretation. Mar. Policy 2014, 44, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-C.; Persada, S.F.; Nadlifatin, R. A Study of Student Behavior in Accepting the Blackboard Learning System: A Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) Approach. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE 18th International Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work in Design (CSCWD), Hsinchu, Taiwan, 21–23 May 2014; pp. 457–462. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jani, M.A.; Sari, G.I.P.; Pribadi, R.C.H.; Nadlifatin, R.; Persada, S.F. An investigation of the influential factors on digital text voting for commercial competition: A case of indonesia. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 72, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shook, C.L.; Ketchen, D.J.; Hult, G.T.M.; Kacmar, K.M. An assessment of the use of structural equation modeling in strategic management research. Strat. Manag. J. 2004, 25, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, P.W.; Wu, Q. Introduction to structural equation modeling: Issues and practical considerations. Edu. Meas. Issues Pract. 2007, 26, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.P.; Ho, M.-H.R. Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, E.J.; Harrington, K.M.; Clark, S.L.; Miller, M.W. Sample size requirements for structural equation models: An evaluation of power, bias, and solution propriety. Edu. Psychol. Meas. 2013, 73, 913–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Construct | Measurement Item | |

|---|---|---|

| PAS | PAS 1 | I have had a chance to use green skincare products through the pro-environmental policy implemented in the green company. |

| PAS 2 | Green skincare companies give me the freedom to make my own decision to use green skincare products. | |

| PAS 3 | I feel that I have the option to use green skincare products. | |

| PEC | PEC 1 | Environmental awareness is influencing me to use green skincare products. |

| PEC 2 | Environmental awareness makes me want to purchase green skincare products. | |

| PEC 3 | I am very worried about the state of the world environment and what that will mean for my future, so I need to protect the environment by using green skincare products. | |

| AT | AT 1 | For me, using green skincare products occurs when the manufacturer appropriately implements their green business. |

| AT 2 | For me, using the green skincare is wise. | |

| AT 3 | For me, using the green skincare is favorable/enjoyable. | |

| SN | SN 1 | My family and close friends recommend that I use green skincare products. |

| SN 2 | My family and close friends would prefer that I use green skincare products. | |

| SN 3 | My family and close friends want me to use green skincare products. | |

| BI | BI 1 | I am likely to buy green skincare products. |

| BI 2 | I will buy green skincare products as soon as I run out of the skincare products I am currently using. | |

| BI 3 | I will recommend green skincare products to other people. | |

| Factor | Item | Factor Loading (≥0.7) 1 | Cronbach Alpha (≥0.7) 1 | CR (≥0.6) 1 | AVE (≥0.5) 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAS | PAS1 | 0.760 | 0.842 | 0.847 | 0.650 |

| PAS2 | 0.831 | ||||

| PAS3 | 0.825 | ||||

| PEC | PEC1 | 0.917 | 0.880 | 0.886 | 0.722 |

| PEC2 | 0.865 | ||||

| PEC3 | 0.760 | ||||

| AT | AT1 | 0.705 | 0.790 | 0.791 | 0.559 |

| AT2 | 0.795 | ||||

| AT3 | 0.740 | ||||

| SN | SN1 | 0.827 | 0.905 | 0.904 | 0.760 |

| SN2 | 0.888 | ||||

| SN3 | 0.899 | ||||

| BI | BI1 | 0.838 | 0.895 | 0.860 | 0.673 |

| BI2 | 0.841 | ||||

| BI3 | 0.780 |

| Statistic | Value | |

|---|---|---|

| The Proposed Model | Recommended | |

| 1. /df | 2.096 | ≤3 [57] |

| 2. CFI | 0.96 | ≥0.9 [57] |

| 3. TLI | 0.95 | ≥0.9 [57] |

| 4. RMSEA | 0.066 | <0.08 [67] |

| Correlation between Factors | Β | P | Hypothesis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT | <--- | PAS | 0.308 | 0.016 ** | H1: supported |

| SN | <--- | PAS | 0.298 | 0.008 *** | H2: supported |

| PEC | <--- | PAS | 0.596 | 0.002 *** | H3: supported |

| AT | <--- | PEC | 0.499 | 0.003 *** | H4: supported |

| SN | <--- | PEC | 0.220 | 0.100 * | H5: supported |

| BI | <--- | AT | 0.607 | 0.003 *** | H6: supported |

| BI | <--- | SN | 0.345 | 0.002 *** | H7: supported |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chin, J.; Jiang, B.C.; Mufidah, I.; Persada, S.F.; Noer, B.A. The Investigation of Consumers’ Behavior Intention in Using Green Skincare Products: A Pro-Environmental Behavior Model Approach. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3922. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10113922

Chin J, Jiang BC, Mufidah I, Persada SF, Noer BA. The Investigation of Consumers’ Behavior Intention in Using Green Skincare Products: A Pro-Environmental Behavior Model Approach. Sustainability. 2018; 10(11):3922. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10113922

Chicago/Turabian StyleChin, Jacky, Bernard C. Jiang, Ilma Mufidah, Satria Fadil Persada, and Bustanul Arifin Noer. 2018. "The Investigation of Consumers’ Behavior Intention in Using Green Skincare Products: A Pro-Environmental Behavior Model Approach" Sustainability 10, no. 11: 3922. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10113922

APA StyleChin, J., Jiang, B. C., Mufidah, I., Persada, S. F., & Noer, B. A. (2018). The Investigation of Consumers’ Behavior Intention in Using Green Skincare Products: A Pro-Environmental Behavior Model Approach. Sustainability, 10(11), 3922. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10113922