1. Introduction

Stone’s [

1] regime theory (RT) has been widely applied to analyze the rise of governing coalitions and public-private coordination since the late 1980s. However, RT studies have mostly focused on urban areas. In contrast, rural communities are often located at the human-nature interface with traditional cultures, agricultural production, and ecological landscape. Owing to the loss of population and agriculture under urbanization, good rural governance relies on coordination between the government and communities. This idea is related to RT [

2]; however, the explanatory ability must be explored further even if the theory has been applied to a few rural studies [

3,

4,

5,

6].

Exploring rural regimes can help explain the capacity to act in rural communities. It is useful to audit whether the participatory action is powerful for community members, whether empowerment is sufficient to shape the community networks, and whether the communication medium is effective for integrating local actions. These questions are associated with the collaborative network of rural communities and the informal arrangement stressed by the RT [

1].

RT inspires two critical issues to explore the experience of rural governance. First, most studies on RT have focused on the issues of urban governance in the last five years [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Second, the information society had been premature when the RT emerged in the 1980s. Currently, social network services (SNSs) that work over electronic communication media have become an essential tool for interpersonal interactions. Therefore, we must rethink whether the rise of e-participation through SNSs enables the formation of rural regimes.

Thus, this study explores the case of the Balien River basin conservation in New Taipei City, Taiwan. We focused on the coordinative experience of river-basin conservation to highlight these issues: (1) How do community members, organizations, and public authorities set up governing agendas to execute river-basin conservation? (2) Why has the mode of river-basin conservation been transformed from government-led top-down intervention to community-based bottom-up governance? (3) How does the power geometry change with the help of SNSs in the process of regime formation? To deal with these issues, we conducted several interviews in the research area and a performed social network analysis by examining the context of group messages on LINE, a popular mobile communication app in Taiwan.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews key concepts such as community, governance, and regime.

Section 3 presents research propositions based on rural regimes and e-participation.

Section 4 introduces some background regarding the research area and an outline of community organizations.

Section 5 highlights the institutional evolution of rural community conservation.

Section 6 examines the social production of rural regimes and the influence of network communities through SNSs. Finally,

Section 7 presents the conclusions.

2. Community, Governance, and Regime

2.1. Community as Arena of Network Governance

The community is the basic social place and geographical scale of public affairs as well as an interactive platform between public and private spheres. It is often defined as “people in a specific area who share common ties and interact with one another” [

13]. Accordingly, the management of community affairs, place-remaking, and interpersonal interactions reveal complicated social networks and the difficulty of conducting government intervention. Furthermore, people play a key role in community networks because “governments rarely have sufficient means to solve all problems in an area. Local people can bring additional resources, which are often essential…[and] create a sense of community” [

14]. Undoubtedly, the community is the arena of network governance.

Contemporary policy-making processes are usually situated in a complex and ever-changing environment, which covers multiple sectors or boundary-spanning spheres. Unlike ‘government’, ‘governance’ can be termed as a flexible policy-making process based on individual networks, especially strong associations between governments and non-governmental actors [

15]. Accordingly, network governance integrates non-formal social networks of non-state actors in addition to formal government systems of actors [

16].

Beyond the market or hierarchy, the network is the agent of governance. It can share resources or knowledge through interpersonal relationships and trust mechanisms to help individual groups cooperate with each other beyond formal procedures or frameworks. Furthermore, the network often spans the boundary and eliminates the restrictions of legislatures. The maintenance of coherence is led by common values and not by a single policy goal [

17]. Successful community development relies on informal networks among people, groups, and organizations. The major function of a community network is to “enhance people’s ability to cope with difficulties and disasters” [

17].

2.2. Community as Social Network of Regime Production

Many studies have noted the importance of citizen participation in community development since the 1950s. The most representative studies are from Hunter [

18] and Dahl [

19]. Hunter’s study is considered elitist because it argues that community affairs are determined by a few local elites with a good reputation and social status. In contrast, Dahl’s study is considered pluralist because it stresses that community affairs in a democratic society are not oligarchic politics but are games played by diversified actors. Despite the different viewpoints, both recognize that participation is a measure of sharing power and rectifying the problem of government corruption. However, community affairs have been complicated gradually and have come to rely on information technology. It is difficult to make decisions correctly with either approach. As stated in one study, “even experts were sometimes baffled…[but] participation may not always be such a good thing” [

20].

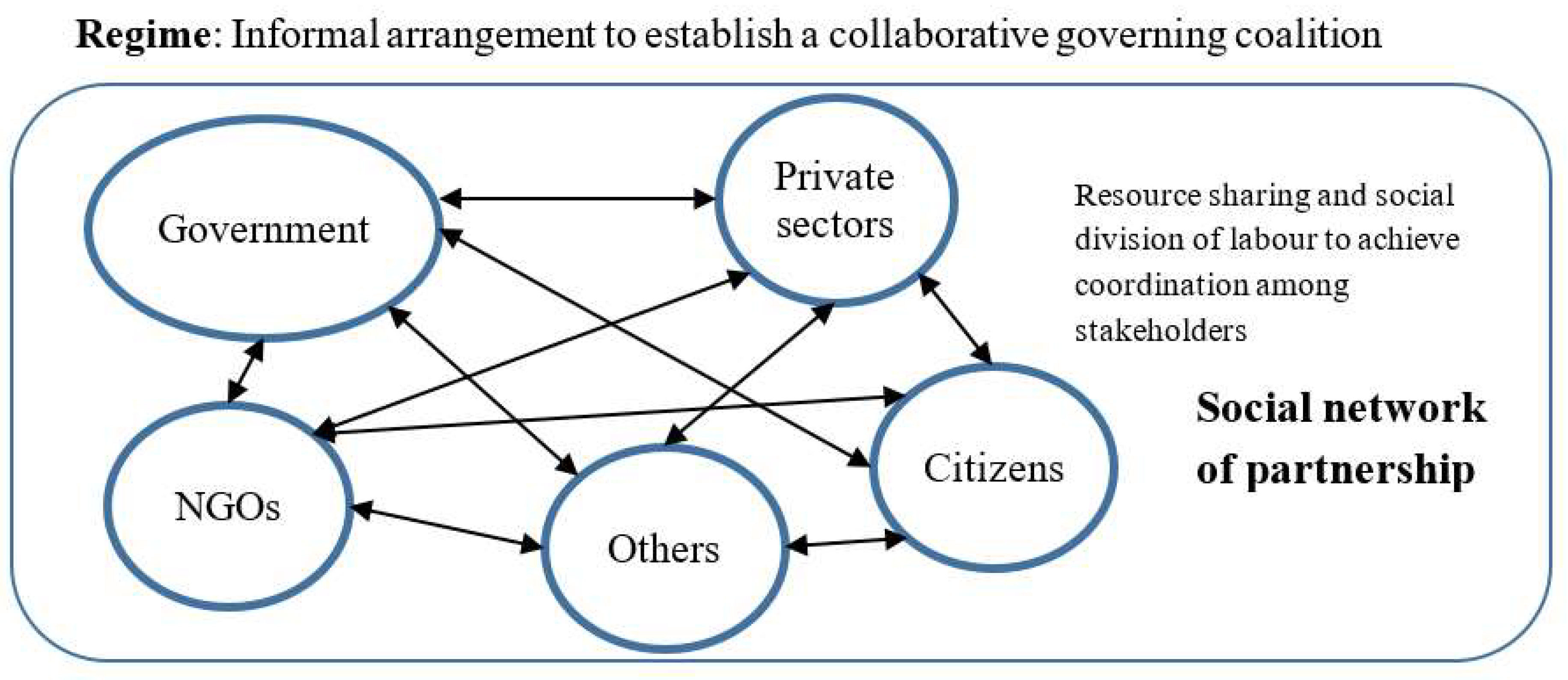

Stone [

1] adopted both viewpoints but slightly favors the pluralist perspective. He proposed RT to explain community governance and the pattern of power allocation. A regime is defined as “the informal arrangements by which public bodies and private interests function together to be able to make and carry out governing decisions” [

1] (6). Governing coalition is a way of regime making to bring together various elements of a community and the different resources [

1]. An informal arrangement is crucial in this coalition because the government alone cannot create effective governance unless non-governmental actors engage in the cooperation with their various resources. Thus, regime theory can be defined as a diffuse and interactive decision-making process based on an informal cooperation between governments and non-governmental agencies to create governing capacities (

Figure 1).

RT has also faced several criticisms. First, RT focuses on the local level in which it is difficult to explore the influence of outer, interscalar, and global factors on local governance [

10,

21]. Second, most urban regimes, in the context of multiple involvements, are business-led or corporate-led [

10,

22], although Marxists and regulationists often doubt whether governing coalition is truly formed equally and publicly without any prevailing bias in a capitalist society [

23,

24,

25]. Third, RT originates from American urban politics, and therefore, its applicability to non-American cases is doubted [

26]. Last, RT seldom investigates the socio-economic transformation and the evolution of new agenda-setting [

11].

Although RT seldom considers external or global socio-economic factors, it is a suitable approach for analyzing community networks because community development belongs to the governance at the grassroots level and is not necessarily related to global forces or does not require a set of grand discourses as an analytic framework [

27]. In addition, plural participation still matters even if the power domination or bias may occur in a capitalist society [

11,

28]. RT can help understand how the decision-making process of community affairs establishes partnerships among multiple stakeholders, shares resources, delivers knowledge, and exchanges information, thereby contributing to the linkage of community organizations and networks [

9,

29]. Even if RT is less synthetic than urban governance theory in the context of time-space shifts [

10], Stone [

12] has refashioned RT to encompass new concepts such as multitier political order and periodization for cross-time comparison.

To sum up, the premise of a successful regime is underpinned by its shared goal, direction, and viability. Viability can connect the actors with useful resources and promote the achievement of easier and less problematic goals. Many variegated regimes are beyond the scope of economic growth or property development [

7,

28,

30,

31]. A regime is associated with political empowerment of coalition members to create a governing capacity for cooperation, negotiation, mobilization, and resource-sharing among multi-actors and to generate the network governance at the community level. Thus, community-led river conservation is certainly in consistent with RT.

3. Research Propositions

Variegated community contexts can generate a variety of governing agendas. RT is useful for analyzing the power structures produced by cooperation between the government and various types of communities and by the evolution of community regimes [

13]. However, contemporary regime studies seldom concern rural development and ignore the influence of information and communications technology (ICT) on interpersonal interaction. Considering the application of RT in rural communities and the involvement of ICT in rural life, we address three propositions in this study.

3.1. Regime Theory Can Be Translated to Explain the Governing Experience of Rural Community

RT mainly originates from urban politics, the exception being a set of rural studies by Horlings and her colleagues [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Their works focused on the public-private cooperation network and governance of rural(-urban) regions in the spatial planning system of the European Union and the Netherlands. They considered that owing to the effects of urbanization and regional integration, rural development in the Netherlands is facing the rapid transformation of society, culture, environment, and landscape, thus requiring new network management of public-private partnerships and production–consumption cooperation to deal with challenges. Successful rural sustainable development relies on the ‘vital coalition’ established by community actors—“the relations between public and private partners that are energizing and productive and can create political power and ‘capacity to act’’ [

3]; that is, “self-organized networks of actors that occur in ‘niches” (incubation rooms for innovation)’ [

4]).

These studies indicate that translating RT from urban to rural areas can help clarify the problem of regional policy and self-governing organizations, thereby making interactions among coalition members more feasible [

3,

4]. In fact, either a regime or a vital coalition is characterized as the policy network with reference to the “informal gatherings of semiautonomous actors or individuals that come together for a common purpose and use resources to achieve it” [

32]. The differences between the two are that the regime is conceptually more extensive and stresses the specific integration and co-evolution between public and private sectors at the system level, whereas the vital coalition involves actors, projects, and networks at the grassroots level exercising energetic and productive capacity to act between public and private partners. Hermans [

6] noted that rural regimes represent not only the actor coalition and the rule of achieving goals but also collective knowledge and future visions. This is particularly true in the framework of sustainable development in which no single solution exists among various stakeholders; instead, the common collaborative foundation is pursued under a set of varied discourses.

However, these studies focus on the experiences of rural governance or urban-rural coordination at the regional scale and even elevate the concept into a regional regime at the macro level. Because the community level is still the major research field of RT, our paper intends to examine the explanatory ability of RT in the context of rural communities.

3.2. Influence of SNS Media in Virtual Places on the Regime Formation

RT emerged in the 1980s when ICT and the Internet were less mature and popular than they are today. Nowadays, the Internet can facilitate social activities, interactions, negotiations, and communications in physical places. Horan [

33] noted that digital places at the grassroots level can promote positive interactions between the place community and the interested community. The place community can gather people together at a specific location, and the interested community can transcend a specific location to form a community based on common interests and link physical places. Various community activities such as information sharing, social and professional interactions, networking, and sponsorships can be performed over electronic media (e.g., Internet) that are not bound to fixed places. Mitchell [

34] noted that the traditional meaning of community is challenged as the Internet becomes more popular and pervasive. If computers and the Internet are readily accessible, citizens can enter virtual places to perform social, economic, cultural, and political activities.

Furthermore, the birth of mobile communication devices and the popularity of SNS media have made e-participation platforms more crucial in the field of urban planning and community development. Frick’s [

35] comparative study in Atlanta, Georgia, and the San Francisco Bay Area showed that ICT-based communication platforms have formed a new public virtual sphere that helps citizens set up an alternative channel separate from the official channel for participation and mobilization. Through these alternative media, a leader can instantly consolidate various emotions, connect people with similar viewpoints, create opposing discourses against official regional planning, and mobilize public voices. Digital platforms can also enable participants to produce materials using YouTube, videos, blogs, Facebook, and Twitter and to integrate directly with traditional media such as TV news and newspapers. Grabkowska [

36] noted the experience of e-democracy in Poland in terms of the use of e-media for participation on urban issues to establish a coalition among a set of small NGOs, improve the capacity of bottom-up activist mobilization, promote interactions among members, and consolidate the social network in real life. Peng [

37] focused on preserving the rural social-ecological-productive landscape in Taiwan. Highlighting the popularity of ICT in Taiwanese society, they explored the case of river preservation in the countryside by using a messenger application to enable communication between community actors and public authorities. They found that the messenger application, serving as a digital medium, promoted social interactions, expression of opinions, and effective social learning among actors, thereby helping to build a closer collaborative network for community participants.

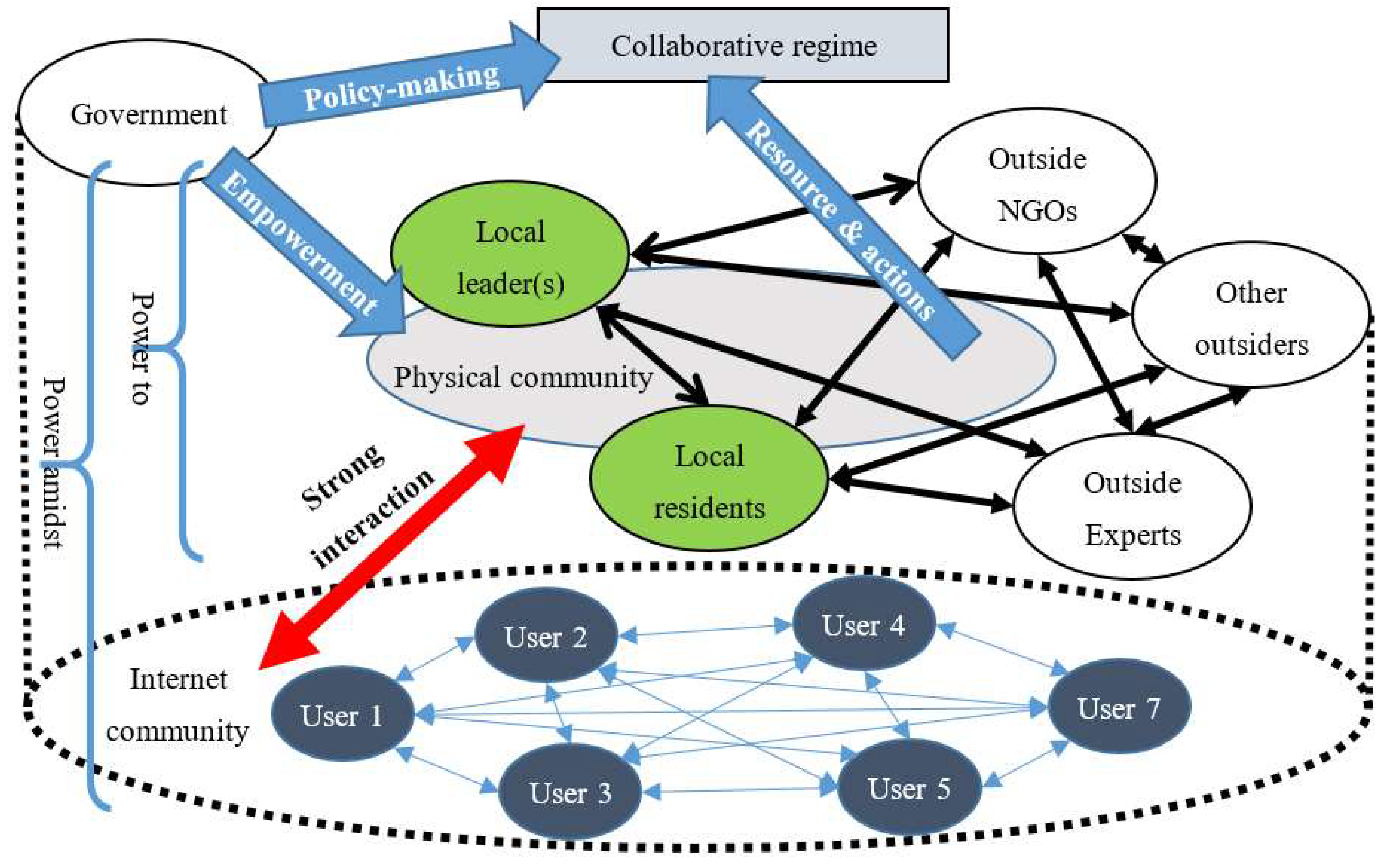

3.3. Power-Amidst—Physical Community and Network Community Can Jointly Construct a Regime

Whether urban, rural or regional, SNS media are undoubtedly beneficial to local cooperation and networked governance of communities. Interpersonal interactions in a virtual place do not entirely supersede those in the physical place; however, they create closer interdependent relationships. Therefore, we can further discuss how the new community and political economy brought about by SNSs affect the informal arrangements of a community regime.

From an RT viewpoint, community power arises from the process of social production among multiple stakeholders involved in the informal arrangement rather than from social control under the legislative framework of the government. In other words, the governing capacity of a community regime emanates from the synergy of power-to—the government empowers other non-governmental actors in a governing coalition—but not power-over—the government controls people through a hierarchical system (Stoker 1995). The concept of social production implies that governing coalitions can evolve with the enduring socio-economic transformation [

11,

12]. In addition, a new networking interaction exists between the virtual place based on SNSs and the physical place that requires face-to-face interaction. The new community network and collaborative coalition jointly constructed by both may reshape a type of community regime.

We argue that SNS-based communication media tend to promote an alternative power geometry facilitating “power-to”—that is, “power-amidst” (

Figure 2). The regime in a physical community is exercised by the governmental empowerment of the community residents, leaders, and related outsiders. By using the “power-to” approach, coalition members can negotiate around common interests, achieve a consensus, and build up a collaboration based on individual functions and divisions between the public and private sectors. However, SNS offers advantages such as instant messaging, just-in-time delivery, simultaneous access, and easy forwarding, and recording. Messaging from virtual places can strengthen interpersonal interactions in physical places, thereby promoting actor networking for informal arrangements in a community regime.

In addition, information in Internet-based communities is public and synonymous. Compared with interactions in a physical community, SNS platforms speed up message feedback, knowledge sharing, and opinion exchanges. A virtual place penetrates geographical boundaries and blurs the social boundaries of members (e.g., profession, status, gender) as “Internet users”, thereby freeing social interactions in Internet-based communities from the constraints of personal identity. The power geometry transforms from “power-to” to “power-amidst”. The emergence of an Internet-based community destructs the given hierarchical system and strengthens informal coordination “amidst” the “Internet users”. If the regime of the physical community has developed a mature collaborative foundation, an Internet-based community can contribute to an advanced, coherent, and networking mode of flexible decisions.

4. Research Area and Methods

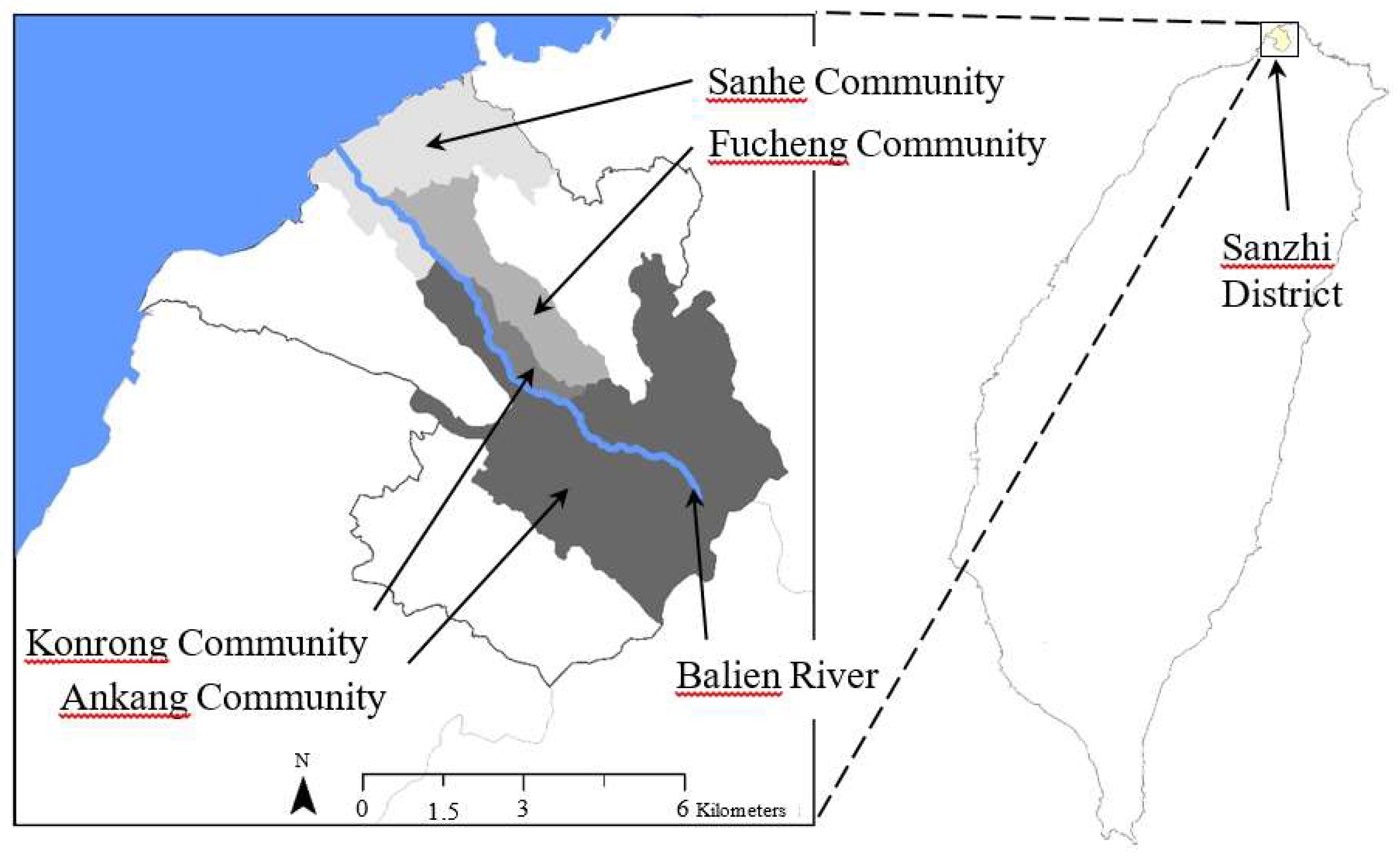

4.1. Background of Communities

This case focuses on four rural communities along the Balien River basin of New Taipei City. We conduct fieldwork in the research area as well as interviews with governmental agencies, community leaders, and residents to explore whether river conservation actions based on community self-governance have stimulated the social production of rural regimes. We also analyze whether the application of SNS media has strengthened the governing capacity of rural collaborative networks. As shown in

Figure 3, the research area is in Sanzhi District in the northern New Taipei City, Taiwan. New Taipei City is currently a special municipality; its predecessor before 2010 was Taipei County. Unlike in Taipei City, the capital of Taiwan, administrative resources at the county level were deficient. Moreover, New Taipei City has an extremely large jurisdiction. Sanzhi District is in a peripheral area with sharp urban-rural disparity. According to official information obtained from the Sanzhi District Office, agriculture is still the paramount local economic base. Although many factories were built in the 1980s, the manufacturing sector has declined owing to industrial outflows since the 2000s. Most of the non-agricultural population includes commuters working in Taipei City. Therefore, the research area is geographically characterized as ‘rural’ although it is jurisdictionally labelled as a part of an urban area.

Owing to the aging population and rapid urbanization, local agriculture is declining, family structure is loosening, and the water and ecology of Balien River are being destroyed by inappropriate engineering. These negative impacts have awakened the need for self-governance through inter-community cooperation to mitigate the environmental problems. The actors of local communities cooperated with each other to address the idea of river conservation with the aim of “river closing and fish protection” (RCFP) in 2006. They formed the Balien River Conservation Guard (BRCG) through inter-community cooperation along the river basin in 2007. Recently, they have engaged in rural regeneration projects promoted by the central government to carry out rural renovation with social, economic, ecological, and cultural dimensions.

Currently, the BRCG contains 34 volunteers. Four patrol segments cover the four communities—Ankang, Gongrong, Fuchen, and Sanhe—from the upper to lower streams. Each segment has a group with a captain and 7–8 teammates. River conservation actions cover a region with 11-km length and 15-km2 area. “Being rural”, the space of each community is not delineated by the administrative jurisdiction of the village but by the natural landscape and significant geometrical features.

4.2. Rural Survey Methodology

This study investigated the evolution of community-led river conservation, with a focus on BRCG, by adopting a qualitative method to retrieve related literature such as research reports, community events, local chronicles, and newspapers. Then, we conducted fieldwork and performed in-depth interviews during March and April 2015 to discuss how community actors affect the proceedings of the governing coalition around conservation actions. Even if several authorities account for the river basin, the Agriculture Economy Division at Sanzhi District Office and the Agriculture Bureau at New Taipei City Government are the major corresponding agencies to contact BRCG and the rural communities owing to the division of governmental accountabilities. Thus, we focus on these agencies and selected 11 interviewees from 34 BRCG members and 3 officers (

Table 1). We used semi-structured interviews of sampled actors who agreed with the opinion survey. When we encountered unclear questions or matters worthy of further exploration from the literature and interviews, we sought more detailed answers from the interviewees through theoretical sampling until we obtained sufficient information. By combining field notes and transcript coding, we qualitatively analyzed various issues in community-led river conservation.

This study also used social network analysis. A social network refers to the relational set between the community actors and their community. Social network analysis investigates the relationships among actors in a place with social interactions [

38]. This method emphasizing the collaboration among different interests and actors is very similar to the concept RT and can visualize the power structure of a regime [

9]. Recently, several RT studies have used social network analysis to analyze the power structure and the interaction among stakeholders because a regime is multilevel networks interlocking actors from the state, market, and civic institutions [

9,

39,

40].

Conceptualizing regimes as fluid networks of interchanging stakeholders can clarify the local interactions and wider geographical settings [

39]. The source of the data is that the researcher draws the LINE conversation data and identifies each message, which is sent to the specific actor (or for the entire group), thereby generating a dual utterance data matrix. Since discussing the structural relationship of power networks is the focus of community development, the concepts of “creating people”, “empowerment” and “bottom-up” are very important.

SNS is a virtual social network for connecting Internet users and enabling their continuous participation, idea exchange, communication, and routine operation [

41]. Notwithstanding, the influence of SNS on a rural regime remains further studied by social network analysis. From interviews with community actors, we found that BRCG’s conservation tasks used traditional interactive channels such as face-to-face contact and telephone calls as well as SNS media such as LINE and Facebook. These facts provide us with the materials to investigate the social network of regime actors.

In the past, most of the social network materials were obtained by means of questionnaires. Through the analysis of LINE content, we can directly understand the changes in the use of resources and the power of different actors in different periods, and the application of new communication technology tools can be clarified. By applying Ucinet 6 social network analysis, we used normalized centrality measures to explore the shift in ‘betweenness centrality’ from 19 July 2014 to 30 September 2015. ‘Betweenness centrality’ refers to the betweenness proportion of the beeline that an actor situates. Specifically, it refers to the rate of the number of beelines passing through an actor and the total number of beelines between two actors. Betweenness centrality can help measure the magnitude that an action can engage in between two actors. The greater its value is, the greater its power is.

5. From Government to Governance: Evolution of Community-led Conservation Action

According to fieldwork in the research area, we acknowledge that the major mission of BRCG is RCFP based on bottom-up collaborative networks. The main subject of river conservation is the water environment intermeshed by the river, surrounding farms, and communities. The community collaborative network originates from the local identity of community residents for whom the river is a living space, the complexity of the bureaucratic system, and the lack of time and human resources to contact the grassroots level and to realize the local embeddedness of culture, life, and nature. The establishment of BRCG reflects the social asymmetry between the mode of top-down government intervention and the local identity of community residents. Owing to the discontent from local people, community-led conservation emerges and further creates the network governance of inter-community cooperation.

5.1. Government Aspect: Multilateral Administration and One-way Hierarchy

In a traditional bureaucratic system, river basin management often involves the problem of the natural hydrology spanning over jurisdictions and conflicts from overlapping authorities along the river basin. In addition to vertical and horizontal inter-governmental integration, inter-sectoral reconciliation is required for reducing functional contestation. Therefore, river basin management involves complicated trade-offs [

42]. In our case study, BRCG was not set up until 2005. Before its establishment, the Balien River was managed by multilateral public authorities with a top-down hierarchy.

The administrative system covers several authorities from central to local levels (

Table 2). In this hierarchy, Pei Kee Irrigation Association is responsible for water resource utilization and the Water Resource Bureau, for river management. The Taipei Branch of the Water and Soil Conservation Bureau is responsible for the upper-stream water and soil conservation zone and the Agriculture Bureau, for supervising ecological conservation along the Balien River. North Coast and Guanyinshan National Scenic Area Administration sometimes performs several public works such as waterfront corridor and river straightening. The District Office plays the roles of negotiator and policy implementer. At this level, Agricultural Economy Division is the major coordinator with BRCG and the public works by Public Work Division has affected the river ecology.

The research area covers multilateral agencies with overlapping accountabilities, fragmentary jurisdictions, and blurred responsibility. For some matters, the problem is that no known authority is clearly responsible. In addition, Pei Kee Irrigation Association is simply a government-funded association whose actions are hardly constrained by the given administrative system. General residents have no chance to participate in the system and have no idea about the individual accountability of each agency. Only Agricultural Economy Division and Public Work Division at the district level are the main agencies interacting with the locals. Social asymmetry exists between public authorities and the communities, resulting in discontent from community leaders:

“District Office does nothing! Fire Bureau does nothing! Police Office does nothing! City Government does nothing! Who is responsible? Only we, just like the troublemakers, fight for every matter at protests.” (Interview F2, 8 March 2015)

5.2. Community Aspect: From the River as a Collective Memory to Rurality Conservation

Community actors consider the Balien River as not only a place for everyday life and leisure but also a source of food production and resource acquisition. The rurality based on the social-ecological-productive landscape links the community life to the natural system of the Balien River. Owing to the emotional relationship between humans and nature, actors are encouraged to be volunteers. However, water pollution influences the quality of life in communities because of pesticide abuse to increase farmland productivity. Moreover, inappropriate river straightening by governmental agencies has exacerbated the destruction of the landscape, biological habitat, and water ecological system.

“If there was no river, there would be no community and neighborhood. Because water is the origin of community life, everyone certainly needs water.” (Interview A2, 21 March 2015)

In the Balien River basin, the water environment, farmland, and rural communities together constitute the life space of farmers, agricultural resources, collective memory, and nature. From the environmental recognition of residents, traditional living has been embedded in the river, representing the multifunctionality with social-ecological-production complexes and consolidating the people, river, and agriculture. Owing to the effects of urbanization and incorrect policy, residents try to recover their traditional feelings about the river, thus stimulating community-led actions for river conservation and rural regeneration.

5.3. Crossover Gap: From Conflicts to Coordination

Since the establishment of BRCG in 2005, the community-led and bottom-up self-governance has started. In the beginning, the public sector still had to become acclimated to managing the river basin under the top-down administrative hierarchy; this opposed the environmental cognition of residents and aroused local resistance. With increased communication between the public and private sectors, a collaboration between the government and communities has emerged with a set of community-led improvements such as reinventing BRCG, confirming community autonomy and division of labor, adopting a digital communication medium, and integrating rural events. Based on the timing of reorganizing BRCG in 2009, the experience can be divided into two stages.

5.3.1. Initial Stage: Conflict and Coordination between Hierarchical Politics and Community Values

The first is the initial stage during 2005–2009. When BRCG was established in 2005, governmental authorities thought about the possibility of community empowerment. However, in practice, they could not eliminate the hierarchical framework owing to the influence of the given administrative system. For example, village heads were initially responsible for BRCG, and patrol areas were delineated according to village jurisdictions, which is the smallest administrative unit in Taiwan. Considering village elections, village heads who were elected by the local residents often tended to deal with illegal activities passively and avoided conflicts. Moreover, village heads served as policy transmitters for superior authorities and as negotiators between the government and residents. Their tasks were often too heavy to handle well, so the residents thought that the practice of river conservation was full of political compromises and that it performed ineffectively.

“It was a mere formality…because they feared to offend the local people with voting rights who illegally went fishing!…I think the patrol area delineated with the village jurisdiction was meaningless because its operation was based on political considerations! The river closing was a formalism.” (Interview F9, 20 April 2015)

“The tasks of river conservation had achieved a little performance before 2011, but BRCG was a loose organization. To do or not to do it was just a nominal routine.” (Interview DG1, 21 March 2015)

Although BRCG could contribute to community participation, the major approach in this stage was still government-led. The Agricultural Economy Division of the District Office could contact the communities, but they only responded to local voices to superior authorities. When faced with matters beyond its jurisdiction, the Agricultural Economy Division had no right to intervene. For example, the river straightening performed by the Public Work Division significantly impacted the water environment; however, the Agricultural Economy Division had no right to rectify it. The Public Work Division never directly provided information about this work to BRCG, and therefore, the community actors often acknowledged activities afterwards and felt no trust toward each other. Owing to many inappropriate public works, the river ecological system deteriorated further and required longer recovery times. The governmental failure saddened BRCG members and exacerbated the government-community conflict.

5.3.2. Developing Stage: Local Rural Vital Coalitions

Owing to the ineffectiveness of river conservation in the prior period, BRCG made use of the upscaling of Taipei County to New Taipei City to introduce new community members and reinvent the organization. As the main agent was transferred from the government to communities, BRCG could be in line with the community residents to negotiate with public authorities and supervise the implementation of river engineering. One interviewee suggested that the reinvention indicates that the key institutional change is ‘taking the locals as the managers’:

“I suggested the task of river conservation again. Then, I changed the operation from the community level. …My idea was to use the locals as the managers to manage the local affairs.” (Interview F2, 8 March 2015)

With increased community-led conservation, community actors could use their local advantage, such as local knowledge about the people and nature, as well as the enthusiasm for river conservation to achieve their goal more easily. Except in the case of river conservation, community division of labor emerged:

“Fuchen community is responsible for the river stream; Gongron community, for riverside pollution; and Ankang Community, for rural culture conservation. We can synchronize these agendas to let the public know of our efforts.” (Interview F9, 20 April 2015)

In addition to the positive interaction between the government and communities, new outside resources have been adopted as communication tools for community networks. Recently, community actors have improved their ecological knowledge by establishing a LINE group and Facebook group for BRCG. Indeed, ICT-based communication platforms can help to instantly report information, share knowledge, and mobilize members for patrols. Community actors suggested setting up a platform, and the Agricultural Economy Division actively participated in communication over the Internet to affirm the use of ICT:

“The benefit of applying LINE in the management is that at any time, we can manage everything because of messaging instantly and operating efficiently. For example, the District Office can collect many resources to reduce the disaster in time.” (Interview F9, 20 April 2015)

“Yep! It is instant, instant! Hey, they just sent back some information today. Sanzhi District Office is organizing a flower festival, so some members like to express their opinions on the LINE group. …He is visiting the festival along the Balien River and sending back the information about the place. It is totally instant and public! That’s it.” (Interview DG1, 21 March 2015)

In the physical communities, various new empowerments have been introduced and transformed into educational and action schemes to manage everyday community affairs. In the past, the residents could only receive information and knowledge from traditional media such as TV, broadcast, and newspapers. The ecological knowledge the residents got was relatively less. As the central government has promoted the application of a rural regeneration programme since 2009, residents prefer to join in community activities such as ecological lectures and rural regeneration training courses organized by the District Office. In addition to the river conservation performance, communities have attempted to promote farmer markets and flower festivals by broadening the community participation and collaborative networks to other dimensions and showing the capacity of rural vitality. With this transformation, key community actors have started to care about the possible future of eco-tourism and local economic development.

6. Social Production of Rural Regime, Integration of Network Community, and Capacity to Conserve under ‘Power-Amidst’

As the BRCG has been reinvented, the bottom-up approach has indeed led to progress in the tasks of river conservation and community division of labor. As noted in the first section, three questions were posed in this study. First, can RT explain the community transformation in the research area? Second, can an ICT-based SNS platform (e.g., LINE and Facebook) help promote the conservation agenda of the rural regime in the research area? Third, how does the Internet community as a communication platform change the power geometry of the rural regime? We explore these questions from the following three aspects.

6.1. Upgrading River Conservation to Rural Regime with Vitality

By observing the evolution of river conservation actions, we found that the governing capacity of BRCG in the initial stage was constrained to the jurisdiction and political consideration. After its reinvention, new members joining the organization exercised the development of community empowerment and dispersion of rural vitality. Recently, community actors have tried to enlarge the categories of the agendas covering a set of new experiments such as environmental education, rural regeneration, farmer’s market, flower festival, and tourism branding to integrate river closing, fish protection, community development, and local revitalization for promoting the benefits of rural conservation.

Before establishing the BRCG in 2005, community residents lacked a channel through which to participate. River management under a jurisdictional system only used a traditional top-down model of governmental intervention without consolidation. They seldom consulted or coordinated with community residents for the details of the project implementation. Their policy-making was distant from actual local demands, so public authorities were often seen as ‘the outsider’, that is, as external public servants, by the local people.

“Before implementing the projects, they’d better inform the details to local people. We can coordinate with each other about how to make it. They will leave here after finishing the engineering, but we still live here! That’s why they should respect the locals.” (Interview F9, 20 April 2015)

The social production of regimes is premised on long-term, stable, and intimate cooperation for creating a common interest between the public and private sectors. Once the collaborative coalition has been established, all participants will engage in fostering the common interest functioned in the long run [

31]. According to Stone’s concept [

1,

30], we argued that three judgements specify the formation of regimes. First, power is underpinned by the ‘social production’ process associated with sufficient empowerment. Second, the regime is premised on an informal arrangement for achieving public-private cooperation. Third, the governing capacity will be generated if the division of labor can be coordinated between the public and private sectors for the collaborative agendas. In our case study, these conditions were not clear before 2005 because the river management policy had no concept of ‘governance’ and only had the typical hierarchical, formalized, and centralized mode of governmental intervention [

15]. Based on the system of ‘power-over’, the decision-making process focused on the administrative authority enforced under the jurisdiction, showing the mode of ‘social control’ [

1]. Therefore, public authorities never cared about whether the locals had been informed or consulted when enforcing their policies; instead, they merely administered projects according to individual jurisdictions.

Even if the circumstances have changed since 2005, we can further divide the latest progress into two periods according to BRCG’s reinvention in 2009. The first is 2005–2009. The municipal government and District Office have recognized the importance of community empowerment; however, the institutional legacy of the hierarchical system was still inherited in the initiative, and the governing mechanism was designed following the formal jurisdictional framework, with the village as the basic unit responsible for river conservation. Because the village heads were the chief promoters, they could not make progress under the pressure of voters and re-election. A transitional period was characterized by institutional dependency in which the mechanism was neither a pure ‘government’ approach nor a fully empowered ‘governance’ mode but a trial-and-error process between the public and private stakeholders searching for a new institution. A gap existed between the policy enforcement and local identity. The initiative was a formalist governance representing ‘social control’ behind the policy-making process. Therefore, river conservation was ineffective, and it exacerbated the social opposition between the government and community actors.

The second stage is after 2009. We can find the significant features of rural regimes according to the three judgements. First, the reinvented BRCG has been community-led and has focused on local identity and environmental ethics. Community actors can fully handle the organization, mobilization, and agenda to make progress with conservation tasks. Local efforts have affected the attitude of public authorities and showed them that they should inform and consult communities before performing river engineering works. Self-governance has matured with improved community empowerment and transformed social control into the social production of power.

Second, the new BRCG has not been constrained to the given administrative system and is now capable of allocating tasks flexibly. By using SNS media such as LINE and Facebook, the governing coalition found it easier to shape the community division of labor, task assignment, information reporting, and objection submission. The mechanism of river basin management has been transformed from a hierarchical system to a flexible collaborative network in a manner similar to the public-private coordination in informal arrangements.

Finally, a consensus has been achieved between the public and private sectors. The cognitive gap and social conflicts have been replaced with positive communications forming collaborative networks in which inter-community cooperation, knowledge learning, and opinion feedbacks contribute to effective governing capacity and create new socio-economic events with rurality. With improved performance and credibility, community solidarity toward river conservation actions led by the BRCG strengthened, thus contributing toward a vital coalition for rural regeneration.

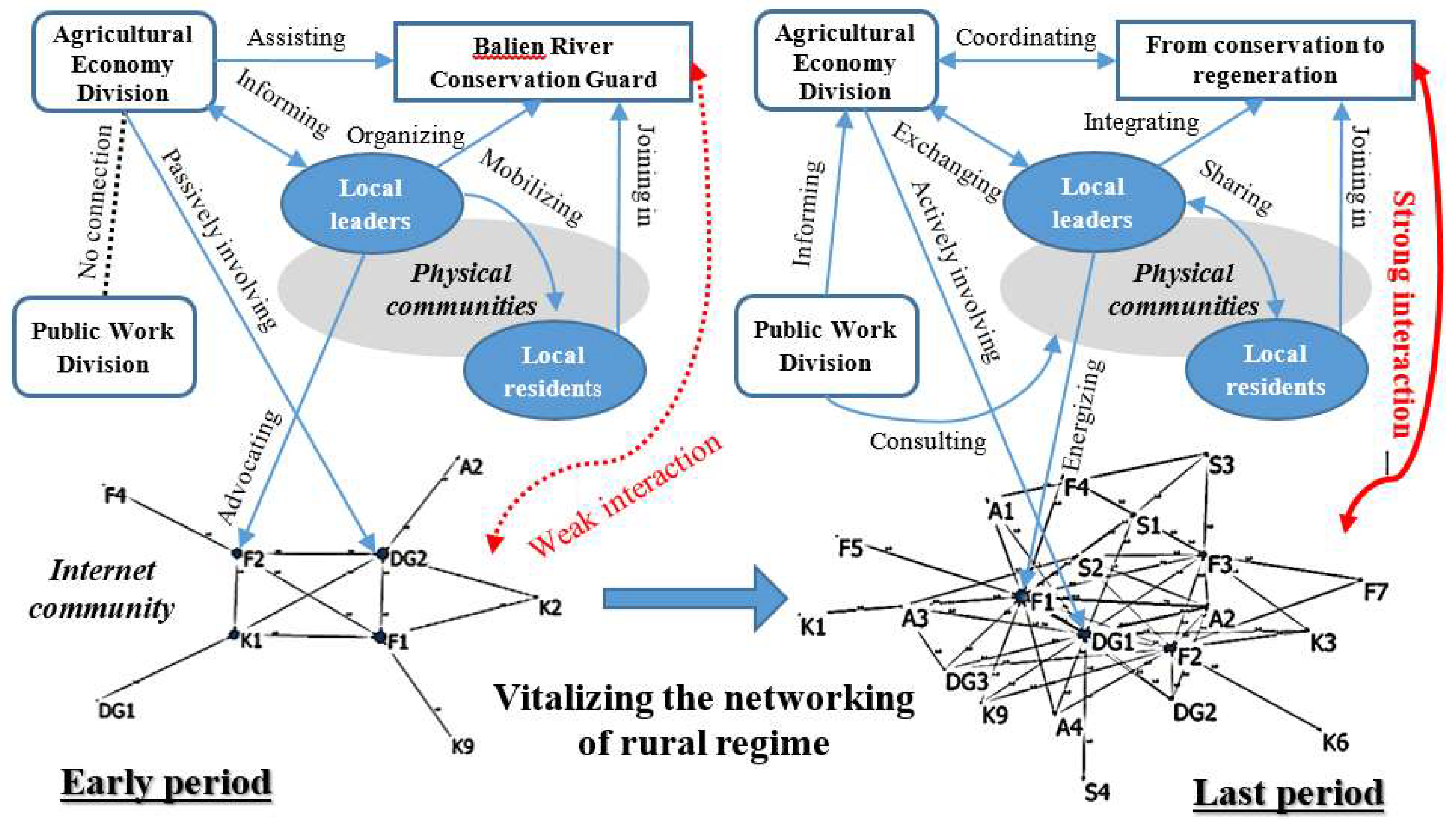

6.2. Influence of SNS Media on Conservation Action of Physical Communities

With the popularity of mobile phones and the Internet, BRCG members decided to use LINE as a communication platform to facilitate contacts related to patrol tasks after 2014. They set up a LINE group to report the situations and problems in the patrol area. Later, Agricultural Economy Division members from the District Office also joined the group, thus improving the coordination, communication, and information exchange between the District Office and communities.

Most BRCG members have joined the LINE group. The group had 30 users. Of these, 27 are locals, including captains, teammates, the chief captain, and the chief executive from the four communities, and three are from the Agricultural Economy Division, including the division chief and two staff members. We conducted social network analysis according to messages in the LINE group during the period from 19 July 2014 to 30 September 2015 to analyze the influence of Internet communication on the action and mobilization of community-led conservation.

Our survey collected 3211 messages and divided them into three periods. In the early period (19 July 2014 to 31 December 2014), the number of messages was relatively low. The maximum number of daily messages was 40. In the middle period (1 January 2015 to 20 June 2015), the maximum number of daily messages increased to 70. In the last period (21 June 2015 to 6 September 2015), the average number of daily messages exceeded 80 and the maximum number exceeded 100.

In addition, the chief captain (F1) and chief executive (F2) are residents of Fuchen Community, and therefore, most messages (1423) were sent by F1 (556) and F2 (312). This fact shows that both actors played the role of leaders in the physical and virtual places to guide others to complete the patrol tasks. Indeed, the use of LINE encouraged collaboration among actors. The role of key actors in SNS media is especially paramount because they can promote effective communication, direct agenda setting and consolidate the emergence of the governing coalition.

According to the Ucinet 6 social network analysis, this study uses normalized centrality measures to explore the shift in betweenness centrality in different periods (

Figure 4 and

Table 3). Betweenness centrality refers to the betweenness proportion of the beeline that an actor situates. This refers to the rate of the number of beelines passing through an actor and the total number of beelines between two actors. Betweenness centrality can help measure the magnitude of an action between two actors. If its value is greater, the power is greater. For each actor, the centrality increases in the later period (e.g., F2, F3, and S1). F1 showed the maximum value (15.147). DG1 is an Agricultural Economy Division staff member who assisted BRCG. He played no role in the early and middle periods, but he actively engaged in the LINE group in the last period. This fact reveals that assigning a role to a public servant can affect his/her participation in SNS media.

6.3. Strengthening Governing Capacity of Physical Communities through Internet Community

Unlike in physical communities, the Internet community based on SNS media can create a virtual place that is instant, public, and sometimes anonymous for every user [

33]. Compared with the public hearings organized under the legislative framework, the Internet platform provides a more informal gateway for interpersonal interaction and simultaneous, clear, and private security for information exchange. When functioning through SNS media, we argue that the social production of regimes tends to evolve a new pattern of power geometry with a diffused, proactive, and permeable social network which can enable member communication and more effective governing capacity. Internet apps (e.g., LINE and Facebook) introduced as tools for routine management after 2014 have had positive impacts on the conservation actions of rural regimes.

6.3.1. LINE Has Become the Major Communication Tool among Community Actors

A captain traditionally assigns and confirms conservation tasks by making a phone call or visiting teammates’ houses. If something illegal happens, traditional communication tools are inconvenient and may require considerable time for teammates to mobilize other partners. After LINE was adopted as the main communication tool, an increasing number of community members and public servants joined the message group. Instant communication improved the efficiency of the daily patrol process.

“The function is instant. …When you patrol the river and find some illegal situations, you alone may not possibly enforce a ban because a phone call is inconvenient. If you send the pictures and messages on LINE, everyone can see what’s the matter and partner assistance will be available soon.” (Interview F9, 20 April 2015)

Through instant interactions using the LINE group, BRCG members can quickly report various information and opinions, including routine contacts, task reports, emergency assistance, river engineering records, and environmental surveys after natural disasters. LINE also provides image and video sharing functions for instantly recording illegal matters and natural impacts. Therefore, the LINE group has become a major bridge connecting BRCG and the Sanzhi District Office.

6.3.2. Informal Interaction between Communities and Public Authorities Increases

As the major communication bridge, the Agricultural Economy Division chief and staff members have also gradually got used to engaging in the group discussion and responding to messages from community members. When BRCG members encounter illegal fishing, other teammates as well as Agricultural Economy Division staff go to the place and call the police for assistance. By using the LINE group, BRCG can rapidly send messages to the District Office and improve the response efficiency to crisis events.

“The most important is the Agricultural Economy Division staff (DG1), a very earnest guy! He goes to the place almost immediately after receiving the message! The efficiency of task enforcement has improved so much!” (Interview F9, 20 April 2015)

“From the perspective of the District Office, we will go to the location where illegal matters are happening at the first time if the teammate calls for assistance and tells me what’s the place.” (Interview DG1, 21 March 2015)

Figure 3 shows the change in the betweenness centrality of the social network between the early and the later periods. In the early period, the main intervenors in the social network were only F1, F2, DG2, and K1. By the later period, the associated users in the group increased and the closer betweenness among F1, DG1, and F2 indicates the strong connection between the chief leaders of the BRCG and Agricultural Economy Division staffs. As the relationships among the LINE group users strengthen, the active interaction between the government and the communities becomes more significant. Compared with the concept shown in

Figure 1, the LINE group as a virtual place has strengthened the positive effect of the collaborative network on consolidating the governing capacity toward community-led conservation.

6.3.3. Community Leaders Use Public Voices on the Internet to Stimulate the Rise of ‘Power-Amidst’

Compared with the privacy of the LINE group, Facebook enjoys the advantages of higher publicity and clarity in the Internet community, and it encourages community actors to post opinions on the platform to express their discontent against inappropriate policies and justify the community-led agenda of river conservation. Interviews with community actors revealed an excellent case in 2015. Owing to improper engineering work by the Public Work Division that endangered the upper stream of the Balien River, locals were discontent with the attitude of the Public Work Division, who did not perform public consultations beforehand and refused to accept the objections from the communities.

Therefore, some community leaders took measures by posting dissenting opinions and propagating the performance of BRCG on Facebook. By using the publicity generated through Facebook, the locals exerted pressure on the public authorities to face the public voice and change their attitudes to solve the problem.

“I surely want to disclose the event through public voices. You can see the article on Facebook. …The headline is ‘To the Outsider Public Servants!’. After posting the article, everybody in Sanzhi heard the news. Then, the District Chief came here to express his apology.” (Interview F9, 20 April 2015)

Subsequently, the District Office and Public Work Division made the Agricultural Economy Division convey relevant engineering information to communities. This event showed that Facebook publicity prompted the generation of public voices and spread influence that helped achieve the aims of the locals. As the shift in network centrality in

Figure 3, the interaction between the government and communities have been closer in the last period, and the instant response and public information have become necessary conditions to consolidate the rural regime. By using Facebook, the locals publicized information that forced the authorities to reply to their voices instantly and transformed the bureaucratic mentality toward active consultation with communities. The virtual place upgraded the social production of ‘power-to’ to ‘power-amidst’, thus highlighting the benefits of the collaborative network.

SNS media used as communication tools have strengthened the governing capacity of river conservation and cultivated informal channels for public-private coordination to exchange opinions. Owing to the publicity generated through Facebook, the requirement for public consultation has pressed the government into rediscovering local demands. As communication channels used by Internet communities have matured, the cognitive disparity between the ‘outsiders’ and the ‘locals’ has been reduced. In the governing context of ‘power-amidst’ prompted by ICT, the ‘informal arrangement of effective public-private coordination’ advocated by Stone [

1] has been created to solidify the social formation of rural regimes in the research area.

7. Conclusions

By translating RT from urban to rural areas, this study tries to explore whether the rural regime has occurred in the collaborative network of river conservation led by rural communities. Then, it analyses how the adoption of SNS media (e.g., LINE and Facebook) to facilitate community-led conservation have affected the governing capacity of inter-community collaborative networks. From the experience of Balien River conservation, we find that the paradigm shift from ‘government to governance’ has emerged in the community-led agenda of river conservation. As the ‘locals’ living in rural communities, the residents have their own environmental ethics and local identity from the experience of everyday life, and it differs from the top-down policy goals from governmental authorities, who are ‘outsiders’ merely concerning jurisdiction.

This case study suggests that the government-centered, top-down, hierarchical system is not highly compatible with local demands arising from the community grassroots level. Instead, the community-led association can be a suitable agency for complementing the institutional vacuum at the grassroots level of the formal administrative system through promoting self-governance and community division of labor. It is a key transition that has contributed to the maturity of the rural regime for carrying out river conservation after 2009.

We consider whether this case conforms to the concept of the regime. The community-led reinvention of BRCG indicates the rise of rural regimes in the inter-community collaborative network. Before 2005, no evidence about governance was available. The major institution of river management was government-led ‘social control’ focusing on the mode of ‘power-over’. Though BRCG was established during 2005–2009, the institutional legacy of the bureaucratic system was still deeply inherited in the process of policy implementation. Constrained by the ideas of jurisdiction and political consideration, river conservation underperformed under formalist governance. After 2009, the reinvention of BRCG contributed to the emergence of community self-governance and agenda set by locals. Hereafter, positive interactions between the government and communities increased. Because of the rise of community division of labor, diversified agendas, including environmental education, knowledge dispersion, rural regeneration, local revitalization, and tourism branding, were created or imagined. The inter-community collaborative network went beyond the scope of environmental conservation and additionally sought comprehensive rural sustainable development with balanced social, environmental, and economic values. The new governing capacity has turned the actions of river conservation into a synergetic vital coalition. The center of community affairs has developed the model of ‘social production’ with the basic features of regimes, namely, the mode of ‘power-to’, informal arrangement, and governing capacity for inter-community cooperation.

In addition, the application of SNS media has facilitated the social production of rural regimes. An analysis of the content of messages on the LINE group of BRCG after 2014 shows that the messages focused on everyday routine patrols, environmental surveys after natural disasters, and engineering supervision. Dividing the experience of using the LINE group into three stages, the number of messages and magnitude of user interaction, revealed that interactions were more frequent in the later period. The social network in the virtual place became more energetic. In particular, the chief leaders of BRCG and Agricultural Economy Division staff interacted with each other actively.

Social network analysis of the LINE group shows that the betweenness centrality increased from the early to the later periods. The data indicated that the solidarity among coalition members improved with frequent interactions on the Internet community, wherein the most intensive interactions came from the community leaders and Agricultural Economy Division staff. This indicates that the informal public-private coordination is improving as it pushes forward the governing capacity of community-led river conservation.

Finally, qualitative interviews on the user experience of SNS media clearly indicate that the LINE group was an effective platform for social interactions. It can improve the quality of communications and discussions and facilitate the reporting of routine patrols or environmental surveys. The social distance between the public and private sectors has decreased. In addition, Facebook, unlike LINE, is much more public and transparent about the posted information; this can force public authorities to listen to public voices. Therefore, these ICT tools help to establish a gateway for informal arrangements complementary to problems the formal administrative system cannot solve. The Internet community can do things in a public and instant manner, thus advancing the governing structure from ‘power-to’ to ‘power-amidst’ and prompting the government to reply to citizens’ opinions in time and fully empower the grassroots level. The Internet community has strengthened the coherence of the governing coalition between the authorities and physical communities. The phenomenon of ‘power-amidst’ brings about the social production of the inter-community collaborative network. Within the new power geometry, the rural regime has been stabilized in the collaborative communities along the Balien River basin.

The institutional transformation of community development evolves gradually and is not observed immediately in the short-term. Our study focuses on the primary stage of BRCG reinvention and the influence of SNS media on community-led river conservation. 2014-2015 is an infancy period for the community actors to adopt in SNS media to operate their coalition. This period provides the key timing to observe the socio-political change of BRCG and the emergence of a governing coalition. However, it is also our limitation in this research. Considering the importance of long-term tracking, the focus of our further research will collect and follow up more long-term data of SNS messages among the stakeholders in the regime to investigate the advanced transformation of existent members and newcomers. Even if the data we used have not covered longer period at this moment, the primary result of this study has revealed the policy implication that the locals are the key actors and central partners for public authorities to achieve better policy effectiveness. The governments should reduce the extent of top-down intervention and empower the locals to self-govern their localities. The vitality of rural communities can energize governing capacities and the use of SNS media advances the progress of governing coalitions.