Events and Tourism Development within a Local Community: The Case of Winchester (UK)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Multiform Concept of Wellbeing

2.1. The Quality of Life (QOL)

2.2. Festivals and Community Quality of Life (QOL)

2.3. Tourism and Quality of Life (QOL) of Residents: Anatomy of the Investigated Phenomenon

3. Methodology

3.1. Background

3.2. Contextual Framework: Winchester

3.3. Winchester: A Special Interest Tourism and Events (SITE) Destination

3.4. Survey

- Facebook Groups (We Are Winchester; Winchester Rants; Winchester Pics; Winchester Bloggers; etc.)

- LinkedIn

- Twitter (Winchester Business Improvement District [BID], Festivals in Winchester, Visit Winchester, Winchester City Council)

- Winchester (BID) newsletter

- Alumni mailing list for the University of Winchester

3.5. Data Analysis

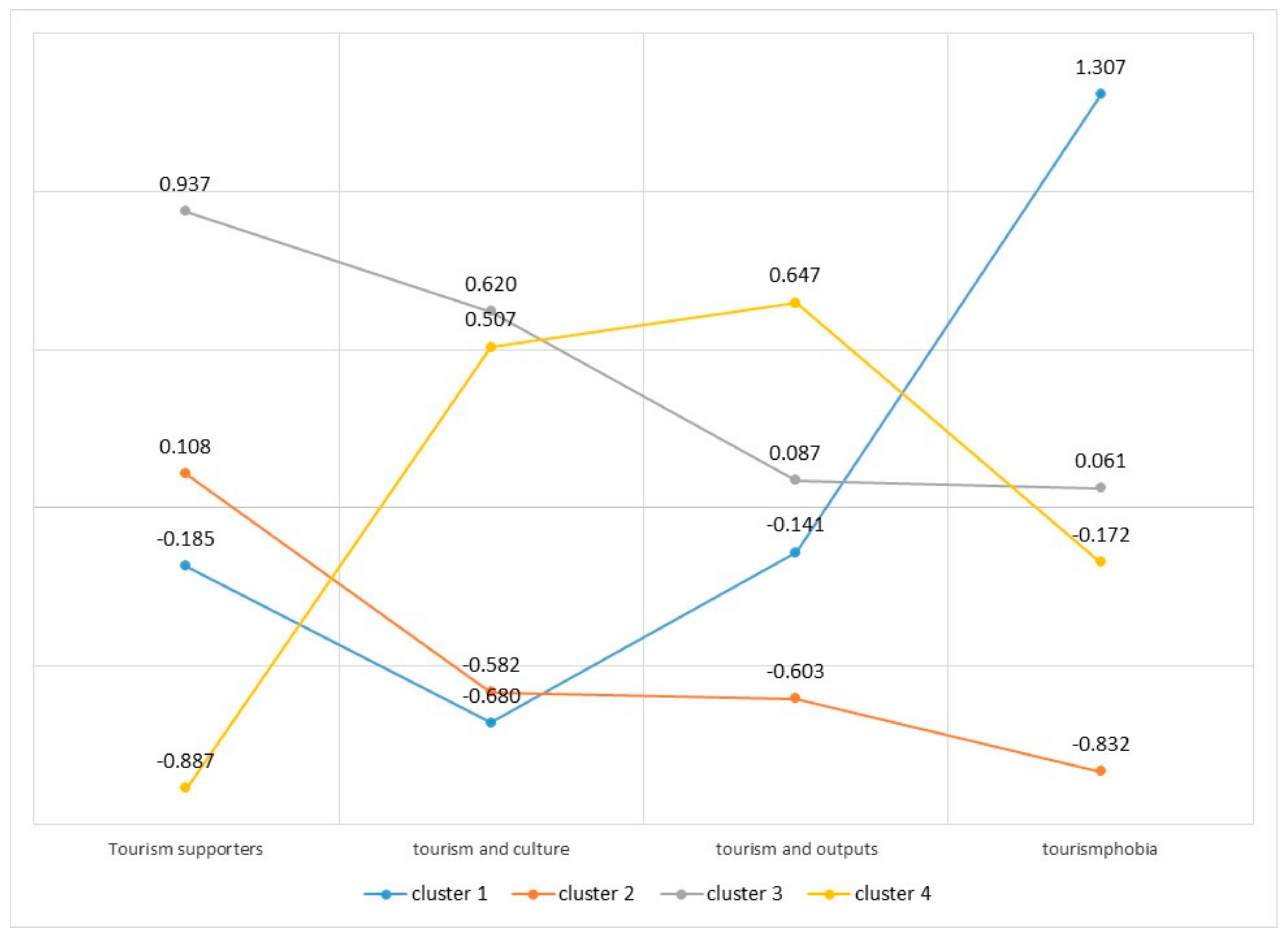

4. Results

4.1. Brief Overview

4.2. Link between Tourism and the Level of Happiness of Residents

4.3. Link between the Level of Happiness of Residents and Events

5. Conclusions

5.1. Summary

5.2. Key Findings and Contributions

5.3. Implication for Winchester

5.4. SITE Destinations’ Branding as a Way to Avoid Overtourism

5.5. Limitations of the Paper and Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Sections | Statements |

|---|---|

| sociodemographic information | |

| Living residence (express in wards) | |

| Age | |

| Number of children | |

| occupation | |

| Gender | |

| wellbeing dimension * | |

| If I could live my life over, I would change nothing | |

| I can find the time to do most everything I want to do | |

| I laugh a lot | |

| I often think of what I should have done differently in my life | |

| I think about the good things that I have missed out on in my life | |

| It gives me pleasure to think of my past | |

| I make decisions on the spur of the moment | |

| It is important to put excitement in my life | |

| In uncertain times, I usually expect the best | |

| I am always optimistic about my future | |

| Overall, I expect that more good things will happen to me than bad things | |

| tourism impact * | |

| Tourism brings more investment opportunities to Winchester’s economy | |

| Winchester’s local businesses benefit from tourism | |

| Tourism creates a variety of jobs in Winchester | |

| Tourism development in Winchester disrupts my life | |

| I see tourists in Winchester as intruders | |

| Tourism growth in Winchester has taken advantage of the community | |

| Tourism increases my pride in my culture | |

| Tourists respect my community’s culture | |

| Tourism preserves my community’s culture | |

| Tourism in Winchester makes me more conscious of the need to maintain and improve the appearance of the city | |

| There is a better infrastructure (hotels, car park space, etc) in Winchester due to tourism development | |

| I am satisfied with the manner in which tourism development and planning in Winchester is currently taking place | |

| Tourism development is done with the best interests of Winchester and environment in mind | |

| Tourism in Winchester is a major reason for entertainment and recreational opportunities | |

| Events contribute to the local community enjoyment of life * | |

| Architecture (e.g., Winchester Cathedral’s Stonemasonry Festival) | |

| Children’s (e.g., Children of Winchester Festival) | |

| Christmas (e.g., Winchester Christmas Lights Switch On) | |

| Comedy (e.g., Winchester Comedy Festival, Winchestival) | |

| Fashion (e.g., Winchester Fashion Week) | |

| Film (e.g., Winchester Short Film Festival) | |

| History (e.g., Heritage Open Days) | |

| Horticulture (e.g., Winchester Cathedral’s Festival of Flowers) | |

| Food and drink (e.g., Ginchester, Hampshire Food Festival) | |

| Literature (e.g., Winchester Poetry Festival, Winchester Writers Festival) | |

| Music (e.g., Alresford Music Festival, Boomtown, Graze Festival) | |

| Science (e.g., Winchester Science Festival) | |

| Sports (e.g., Winchester Community Games, Winchester Criterium and Cyclefest) | |

| Arts (e.g., Hat Fair, Winchester Festival, Winchester Mayfest)Events development in Winchester is done with the best interests of the local community and environment in mind | |

References

- Park, S.-Y.; Petrick, J.F. Destinations’ Perspectives of Branding. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 262–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshnevis Yazdi, S.; Khanalizadeh, B. Tourism demand: A panel data approach. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 787–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, G.; Lennon, J.L. (Eds.) Dark Tourism: Practice and Interpretation; Routledge: Abingdon/Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, P.M.; Adams, K.M. The Janus-faced character of tourism in Cuba. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monterrubio, C. Protests and tourism crises: A social movement approach to causality. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 22, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seraphin, H.; Yallop, A.C.; Capatîna, A.; Gowreesunkar, V.G. Heritage in tourism organisations’ branding strategy: The case of a post-colonial, post-conflict and post-disaster destination. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2018, 12, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivlevs, A. Happy Hosts? International Tourist Arrivals and Residents’ Subjective Well-being in Europe. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 599–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croes, R.; Rivera, M.A.; Semrad, K.; Khalizadeh, J. Happiness and Tourism: Evidence from Aruba; The Dick Pope Sr. Institute for Tourism Studies: Orlando, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.; Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J. How does tourism in a community impact the quality of life of community residents? Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benckendorff, P.; Edwards, D.; Jurowski, C.; Liburd, J.J.; Miller, G.; Moscardo, G. Exploring the future of tourism and quality of life. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2009, 9, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimonte, S.; Faralla, V. Does residents’ perceived life satisfaction vary with tourist season? A two-step survey in a Mediterranean destination. Tour. Manag. 2016, 55, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J.; Woo, E.; Kim, H.L. Quality of life (QOL) and well-being research in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Barrios, L.J.; Giraldo, M.; Khalik, M.; Manjarres, R. Services for the underserved: Unintended well-being. Serv. Ind. J. 2015, 35, 883–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croes, R.; Ridderstaat, J.; van Niekerk, M. Connecting quality of life, tourism specialization, and economic growth in small island destinations: The case of Malta. Tour. Manag. 2018, 65, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, L.S.; Wrenn, B. The Essentials of Marketing Research, 3rd ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dolnicar, S.; Lazarevski, K.; Yanamandram, V. Quality of life and tourism: A conceptual framework and novel segmentation base. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 724–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Woo, E.; Uysal, M. Tourism experience and quality of life among elderly tourists. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobson, J.S.P.; Dietrich, U.C. Tourism, Health and Quality of Life. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1995, 3, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, F. Wellbeing: Concepts and Challenges Discussion Paper; Sustainable Development Research Network: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe, S.; Joldersma, T.; Li, C. Understanding the benefits of social tourism: Linking participation to subjective well-being and quality of life. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2010, 12, 761–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Niekerk, M. Community perceptions on the impacts of art festivals and its impact on overall quality of life: A case study of the Innibos National Art Festival, South Africa. In Focus on World Festivals: Contemporary Case Studies and Perspectives; Newbold, C., Jordan, J., Eds.; Goodfellow Publishers Limited: Woodeaton, UK, 2016; p. 333. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, M.; Croes, R.; Lee, S.H. Tourism development and happiness: A residents’ perspective. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2016, 5, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubomirsky, S.; Lepper, H.S. A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and construct validation. Soc. Indic. Res. 1999, 46, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helliwell, J.; Layard, R.; Sachs, J. (Eds.) World Happiness Report 2017; Sustainable Development Solutions Network: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder, K. Cultural Values and Sustainable Tourism Governance in Bhutan. Sustainability 2015, 7, 16616–16630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B.; Lane, B. (Eds.) Tourism Collaboration and Partnerships: Politics, Practice and Sustainability; Channel View Publications: Clevedon, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Crouch, G.I.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Tourism, Competitiveness, and Societal Prosperity. J. Bus. Res. 1999, 44, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeoman, I.; Robertson, M.; Ali-Knight, J.; Drummond, S.; McMahon-Beattie, U. (Eds.) Festival and Events Management: An International Arts and Culture Perspective; Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Laing, J. Festival and event tourism research: Current and future perspectives. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 25, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Kendall, K.W. Hosting mega events. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 603–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, D.M.; Fairley, S. What about the event? How do tourism leveraging strategies affect small-scale events? Tour. Manag. 2018, 64, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jago, L.; Dwyer, L.; Lipman, G.; van Lill, D.; Vorster, S. Optimising the potential of mega-events: An overview. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2010, 1, 220–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, H.; Leopold, T. Events and the Social Sciences, 1st ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, G.; Palmer, R. Eventful Cities: Cultural Management and Urban Revitalisation; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Seny Kan, A.K.; Adegbite, E.; El Omari, S.; Abdellatif, M. On the use of qualitative comparative analysis in management. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1458–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, A.W.; Fernando, I.K. Routine and Project-Based Leisure, Happiness, and Meaning in Life. J. Leis. Res. 2012, 44, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, A.W.; Kang, H.-K.; Schmidt, C. Leisure Routine and Positive Attitudes. J. Leis. Res. 2016, 48, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimonte, S.; Faralla, V. Happiness and nature-based vacations. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 46, 176–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimonte, S.; Faralla, V. Tourist types and happiness a comparative study in Maremma, Italy. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 1929–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimonte, S.; Faralla, V. Happiness and Outdoor Vacations Appreciative versus Consumptive Tourists. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, X.R. Does a happy destination bring you happiness? Evidence from Swiss inbound tourism. Tour. Manag. 2018, 65, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, Y.M.; Chu, M.J.T. Moderating effects of presenteeism on the stress-happiness relationship of hotel employees: A note. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 55, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholipour, H.F.; Tajaddini, R.; Nguyen, J. Happiness and inbound tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 57, 251–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillet, S.; Schmitz, P.; Mitas, O. The Snap-Happy Tourist. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2016, 40, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, J.P.-H.; Jaw, C.; Huan, T.-C.; Woodside, A.G. Applying complexity theory to solve hospitality contrarian case conundrums. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 608–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalilzadeh, J.; Ghahramani, L.; Tabari, S. From “Hypercritics” to “Happy Campers”: Who Complains the Most in Fine Dining Restaurants? J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2017, 26, 451–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, S.; Saayman, M.; Ellis, S. The Influence of Travel Motives on Visitor Happiness Attending a Wedding Expo. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2014, 31, 649–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, J.; Mao, Z.; Hu, L. Cruise experience and its contribution to subjective well-being: A case of Chinese tourists. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 20, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, S.; Johnson, S. The happiness factor in tourism: Subjective well-being and social tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 41, 42–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawijn, J. The holiday happiness curve: A preliminary investigation into mood during a holiday abroad. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2010, 12, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawijn, J. Determinants of Daily Happiness on Vacation. J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, Y.; Nawijn, J.; Peeters, P.M. Happiness and limits to sustainable tourism mobility: A new conceptual model. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 1017–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiers, A.; Walker, G.J. The Effects of Ethnicity and Leisure Satisfaction on Happiness, Peacefulness, and Quality of Life. Leis. Sci. 2008, 31, 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorakis, N.D.; Kaplanidou, K.; Karabaxoglou, I. Effect of Event Service Quality and Satisfaction on Happiness Among Runners of a Recurring Sport Event. Leis. Sci. 2015, 37, 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaur, S.-H.; Yen, C.-H.; Hsiao, S.-L. Transcendent Experience, Flow and Happiness for Mountain Climbers. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 15, 360–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G.J.; Ito, E. Mainland Chinese Canadian Immigrants’ Leisure Satisfaction and Subjective Well-Being: Results of a Two-Year Longitudinal Study. Leis. Sci. 2017, 39, 174–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Huang, S.; Stodolska, M.; Yu, Y. Leisure Time, Leisure Activities, and Happiness in China. J. Leis. Res. 2015, 47, 556–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.; Weiler, B. Introduction. What’s special about special interest tourims? In Special Interest Tourism; Hall, M., Weiler, B., Eds.; Bellhaven Press: London, UK, 1992; p. 224. [Google Scholar]

- Trauer, B. Conceptualizing special interest tourism—Frameworks for analysis. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H. Heritage Tourism; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, X.C.; Sparks, B. Barriers to offering special interest tour products to the Chinese outbound group market. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, W. Events Feasibility and Development: From Strategy to Operations; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Raj, R.; Walters, P.; Rashid, T. Events Management. Principles & Practice, 3rd ed.; SAGE: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bowdin, G.; Allen, J.; Harris, R.; McDonnell, I.; O’Toole, W. Events Management, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, A. Tourism, Poverty and Development; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kirillova, K.; Fu, X.; Lehto, X.; Cai, L. What makes a destination beautiful? Dimensions of tourist aesthetic judgment. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, P.; Sharpley, R. Local perceptions of the relative contributions of enclave tourism and agritourism to community well-being: The case of Mauritius. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2016, 5, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesonen, J.; Komppula, R. Rural Wellbeing Tourism: Motivations and Expectations. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2010, 17, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zografos, C.; Allcroft, D. The Environmental Values of Potential Ecotourists: A Segmentation Study. J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 15, 44–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konu, H. Identifying potential wellbeing tourism segments in Finland. Tour. Rev. 2010, 65, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrovski, D.; Todorović, A. Clustering wellness tourists in spa environment. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 16, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesonen, J.A. Testing Segment Stability: Insights from a Rural Tourism Study. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2014, 31, 697–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullagh, P. Regression Models for Ordinal Data. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 1980, 42, 109–142. [Google Scholar]

- Alegre, J.; Cladera, M. Repeat Visitation in Mature Sun and Sand Holiday Destinations. J. Travel Res. 2006, 44, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott Long, J. Regression Models for Categorical and Limited Dependent Variables; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Seraphin, H.; Gowreensunkar, V.; Ambaye, M. The Blakeley Model applied to improving a tourist destination: An exploratory study. The case of Haiti. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2016, 5, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, L. Cointégration et causalité entre développement touristique, croissance économique et réduction de la pauvreté: Cas de Haïti [Cointegration and Causality Between Tourist Development, Economic Expansion and proverty reduction in Haiti]. Études Caribéennes 2009, 13–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, K.S.; Rice, E. Social Exchange Theory. In Handbook of Social Psychology; Springer US: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 53–76. [Google Scholar]

- Haifeng, Y.; Jing, L.; Mu, Z. Rural community participation in scenic spot. A case study of Danxia Mountain of Guangdong, China. J. Hosp. Tour. 2012, 10, 76–112. [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social Exchange Theory: An Interdisciplinary Review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muresan, I.; Oroian, C.; Harun, R.; Arion, F.; Porutiu, A.; Chiciudean, G.; Todea, A.; Lile, R. Local Residents’ Attitude toward Sustainable Rural Tourism Development. Sustainability 2016, 8, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitras, D.; Muresan, I.; Ilea, M.; Jitea, I. Agritourism—A Potential Linkage Between Local Communities and Parks to Maintain Sustainability. Bull. UASVM Horitc. 2013, 70, 300–309. [Google Scholar]

- Pera, R.; Viglia, G. Turning ideas into products: Subjective well-being in co-creation. Serv. Ind. J. 2015, 35, 388–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowreesunkar, V.G.B.; Séraphin, H.; Morrison, A. Destination Marketing Organisations: Roles and Challenges. In The Routledge Handbook of Destination Marketing; Gursoy, D., Chi, C.G., Eds.; Taylor & Francis Ltd.: London, UK, 2018; pp. 16–34. [Google Scholar]

- Seraphin, H.; Sheeran, P.; Pilato, M. Over-tourism and the fall of Venice as a destination. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 374–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, K.B. Researching Internet-Based Populations: Advantages and Disadvantages of Online Survey Research, Online Questionnaire Authoring Software Packages, and Web Survey Services. J. Comput. Commun. 2006, 10, JCMC1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewlett, D.; Harding, L.; Munro, T.; Terradillos, A.; Wilkinson, K. Broadly engaging with tranquillity in protected landscapes: A matter of perspective identified in GIS. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 158, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modica, G.; Zoccali, P.; Di Fazio, S. The e-Participation in Tranquillity Areas Identification as a Key Factor for Sustainable Landscape Planning. In Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2013, Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Murgante, B., Misra, S., Carlini, M., Torre, C.M., Nguyen, H.-Q., Taniar, D., Apduhan, B.O., Gervasi, O., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 7973, pp. 550–565. [Google Scholar]

- Johansen, S. Statistical analysis of cointegration vectors. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 1988, 12, 231–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granger, C.W.J. Some recent development in a concept of causality. J. Econom. 1988, 39, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author(s) | Year | Article | Journal | Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bailey & Fernando [36] | 2017 | Routine and project-based leisure, happiness and meaning in life | Journal of Leisure Research | Leisure activities (outdoor) contribute to happiness |

| Bailey, Kang & Schmidt [37] | 2017 | Leisure routine and positive attitudes: Age-graded comparisons of the path to happiness | Journal of Leisure Research | Leisure activities (routine) contribute to happiness |

| Bimonte & Faralla [38] | 2014 | Happiness and nature-based vacations | Annals of Tourism Research | Nature contributes to tourists’ well-being |

| Bimonte & Faralla [39] | 2012 | Tourist types and happiness a comparative study in Maremma, Italy | Annals of Tourism Research | Type of vacation impacts on tourists’ happiness |

| Bimonte & Faralla [11] | 2016 | Does residents’ perceived life satisfaction vary with tourist season? A two-step survey in Mediterranean destination | Tourism Management | Life satisfaction of residents vary with tourist season |

| Bimonte &Faralla [40] | 2015 | Happiness and outdoor vacations appreciative versus consumptive tourists | Journal of Travel Research | Tourists involved in more appreciative activities are more concerned about the environment and are happier |

| Chen & Li [41] | 2018 | Does a happy destination bring you happiness? Evidence from series from Swiss inbound tourism | Tourism Management | Tourist satisfaction has an effect on tourist happiness |

| Chia & Chu [42] | 2016 | Moderating effects of presentism on the stress-happiness relationship of hotel employees: A note | International Journal of Hospitality Management | Employees’ happiness |

| Croes, Ridderstaat, Van Van Niekerk [14] | 2018 | Connecting quality of life, tourism specialisation and economic growth in small island destinations: The case of Malta | Tourism Management | Tourism specialisation improves the residents QOL but only on the short term |

| Gholipour, Tjajaddini & Nguyen [43] | 2016 | Happiness and inbound tourism | Annals of Tourism Research | The level of happiness of the locals contribute to attract visitors |

| Gillet, Schmitz & Mitas [44] | 2013 | The snap-happy tourist. The effects of photographing behaviour on tourists’ happiness | Journal of Hosp Tourism Research | There is a correlation between the level of tourists’ happiness and photography |

| Hsiao, Jaw, Huan & Woodside [45] | 2015 | Applying complexity theory to solve hospitality contrarian case conundrums: Illuminating happy-low and unhappy-high performing frontline service employees | International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, | Model to evaluation of employees’ happiness |

| Ivlevs [7] | 2017 | Happy hosts? International tourists’ arrivals and residents’ subjective well-being in Europe | Journal of Travel Research | Tourist arrivals impact negatively residents’ life satisfaction |

| Khalizadeth, Ghahramani &Tabari [46] | 2017 | From ‘hypercritics’ to ‘happy campers’: Who complains the most in fine dining restaurants? | Journal Hosp Marketing Management | Happy customers are unlikely to complain |

| Kruger, Saayman & Ellis [47] | 2014 | The influence of travel motives on visitor happiness attending a wedding expo | Journal of Travel Tourism Marketing | Attribute of wedding expo contribute to enhance visitors happiness QOL |

| Lyu, Mao & Hu [48] | 2018 | Cruise experience and its contribution to subjective well-being: A case of Chinese tourists | International Journal of Tourism Research | Holidays contributes to subjective well-being |

| Mcabe, Joldersmna & Li [20] | 2010 | Understanding the benefits of social tourism: Linking participation to subjective well-being and quality of life | International Journal of Tourism Research | Holidays contribute to the increase in QOL of low-income families |

| McCabe & Johnson [49] | 2013 | The happiness factor in tourism: Subjective well-being and social tourism | Annals of Tourism Research | Tourism contributes to social tourist’s well-being |

| Nawjin [50] | 2010 | The holidays curve: A preliminary investigation into mood during a holiday abroad | International Journal of Tourism Research | Level of happiness of tourists fluctuates during holidays |

| Nawjin [51] | 2011 | Determinants of daily happiness on vacation | Journal of Travel Research | Tourism industry as a whole contribute to people happiness despite the fact there is room for improvement |

| Ram, Nawjin & Peeters [52] | 2013 | Happiness and limits to sustainable tourism mobility: A new conceptual model | Journal of Sustainable Tourism | Happy tourists in life are more likely to have sustainable attitude when travelling |

| Spiers & Walker [53] | 2008 | The effects of ethnicity and leisure satisfaction on happiness, peacefulness and quality of life | Leisure Sciences | There is a link between ethnicity and happiness |

| Theodorakis, Kaplanidou & Karabaxoglou [54] | 2015 | Effect of event service quality and satisfaction on happiness among runners of a recurring sport event | Leisure Sciences | Events positively impact on the satisfaction of participants |

| Tsaur, Yen & Hsaio [55] | 2012 | Transcendent experience, flow and happiness for mountain climbers | International Journal of Tourism Research | Mountain climbing contribute to tourists’ well-being |

| Walker & Ito [56] | 2017 | Mainland Chinese Canadian immigrants’ leisure satisfaction and subjective well-being: results of a two-year longitudinal study | Leisure Sciences | Leisure satisfaction positively affect happiness and satisfaction of life |

| Wei, Huang, Stodolska & Yu [57] | 2017 | Leisure time, leisure activities and happiness in China | Journal of Leisure Research | Leisure activities contribute to happiness |

| Jan | Feb | March | April | May | June | July | Aug | Sept | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children of Winchester Festival | Winchester Beer Festival | Easter Bunny Hop | Winchester Mayfest | Winchester Speakers Festival | Winchester Festival | Boomtown | SC4M Americana Music Festival | Harvest Weekend | Bonfire and Fireworks | Woolly Hat Fair | |

| Winchester Fashion Week | Ginchester Fete | Hampshire Food Festival | Cheese & Chilli Festival | Winchester Community Games | Winchester Comedy Festival | Winchester Short Film Festival | |||||

| Winchester Chamber Music Festival | Winchester Criterium and Cyclefest | Southern Cathedrals Festival | Graze Festival | Winchester Jazz Festival | Winchester Poetry Festival | Winchester Christmas Light Switch On | |||||

| Winchester Writers’ Festival | Winchester Science Festival (Winscifest) | Christmas Market and Ice Rink | Christmas Market and Ice Rink | ||||||||

| Winchester School of Art Degree Show | Wine Festival Winchester | ||||||||||

| Winchestival Hat Fair |

| Fashion event | Science events | ||

| Music & comedy events | Children events | ||

| Art & literature events | Food & drink events | ||

| Sport events |

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 244 | 79.2 |

| Male | 64 | 20.8 |

| Age | ||

| Gen z | 83 | 26.9 |

| Gen x | 151 | 49.0 |

| Baby boomers | 74 | 24.0 |

| Respondents with children | 196 | 63.6 |

| Activity | ||

| Employed | 206 | 66.9 |

| Homemaker | 26 | 8.4 |

| Other | 20 | 6.5 |

| Retired | 31 | 10.1 |

| Student | 22 | 7.1 |

| Unemployed | 3 | 1.0 |

| Tourism Dimension Variables Used for Segmentation * | Component | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| fac 1 | Tourism brings more investment opportunities to Winchester’s economy | 0.787 | |||

| fac 2 | Winchester’s local businesses benefit from tourism | 0.833 | |||

| fac 3 | Tourism creates a variety of jobs in Winchester | 0.806 | |||

| fac 4 | Tourism development in Winchester disrupts my life | 0.681 | |||

| fac 5 | I see tourists in Winchester as intruders | 0.774 | |||

| fac 6 | Tourism growth in Winchester has taken advantage of the community | 0.794 | |||

| fac 7 | Tourism increases my pride in my culture | 0.717 | |||

| fac 8 | Tourists respect my community’s culture | 0.746 | |||

| fac 9 | Tourism preserves my community’s culture | 0.767 | |||

| fac 10 | Tourism in Winchester makes me more conscious of the need to maintain and improve the appearance of the city | 0.684 | |||

| fac 11 | There is a better infrastructure (hotels, car park space, etc.) in Winchester due to tourism development | 0.768 | |||

| fac 12 | I am satisfied with the manner in which tourism development and planning in Winchester is currently taking place | 0.853 | |||

| fac 13 | Tourism development is done with the best interests of Winchester and environment in mind | 0.800 | |||

| fac 14 | Tourism in Winchester is a major reason for entertainment and recreational opportunities | 0.644 | |||

| % of variance | 21,744 | 18,515 | 17,563 | 14,762 | |

| Item Code | Item Description | Sample ** | 1 Cluster *** | 2 Cluster *** | 3 Cluster *** | 4 Cluster *** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| It 1 | If I could live my life over, I would change nothing | 3.25 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 1.07 | 1.01 |

| It 2 | I can find the time to do most everything I want to do | 3.31 | 1.08 | 0.95 | 1.01 | 1.01 |

| It 3 | I laugh a lot | 3.92 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 1.03 | 1.01 |

| It 4 | I often think of what I should have done differently in my life | 2.81 | 0.99 | 1.03 | 0.92 | 1.06 |

| It 5 | I think about the good things that I have missed out on in my life | 2.34 | 1.10 | 1.03 | 0.96 | 0.94 |

| It 6 | It gives me pleasure to think of my past | 3.62 | 1.01 | 0.91 | 1.06 | 1.04 |

| It 7 | I make decisions on the spur of the moment | 3.14 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 1.04 | 1.03 |

| It 8 | It is important to put excitement in my life | 3.92 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 1.04 | 1.00 |

| It 9 | In uncertain times, I usually expect the best | 3.30 | 1.01 | 0.93 | 1.02 | 1.05 |

| It 10 | I am always optimistic about my future | 3.66 | 0.98 | 0.92 | 1.04 | 1.06 |

| It 11 | Overall, I expect that more good things will happen to me than bad things | 3.82 | 0.98 | 0.93 | 1.03 | 1.06 |

| Factors | Estimation | Wald | Sig | Exp (B) | % Variance in the Odds |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tourism supporters | 1.630 | 125,322 | 0.000 | 5.101 | 410.1 |

| Tourism culture | 0.945 | 58,446 | 0.000 | 2.572 | 157.2 |

| Tourism and outputs | 0.694 | 33,838 | 0.000 | 2.003 | 100.3 |

| Tourismphobia | 0.746 | 38,985 | 0.000 | 0.474 | −52.6 |

| Cox and Snell: 0.546; Nagelkerke: 0.574 | |||||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Séraphin, H.; Platania, M.; Spencer, P.; Modica, G. Events and Tourism Development within a Local Community: The Case of Winchester (UK). Sustainability 2018, 10, 3728. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103728

Séraphin H, Platania M, Spencer P, Modica G. Events and Tourism Development within a Local Community: The Case of Winchester (UK). Sustainability. 2018; 10(10):3728. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103728

Chicago/Turabian StyleSéraphin, Hugues, Marco Platania, Paul Spencer, and Giuseppe Modica. 2018. "Events and Tourism Development within a Local Community: The Case of Winchester (UK)" Sustainability 10, no. 10: 3728. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103728

APA StyleSéraphin, H., Platania, M., Spencer, P., & Modica, G. (2018). Events and Tourism Development within a Local Community: The Case of Winchester (UK). Sustainability, 10(10), 3728. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103728