Examining the Conflicting Relationship between U.S. National Parks and Host Communities: Understanding a Community’s Diverging Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Framework for Analysis

3.1. The Substance Dimension

3.2. The Procedure Dimension

3.3. The Relationship Dimension

4. Methods

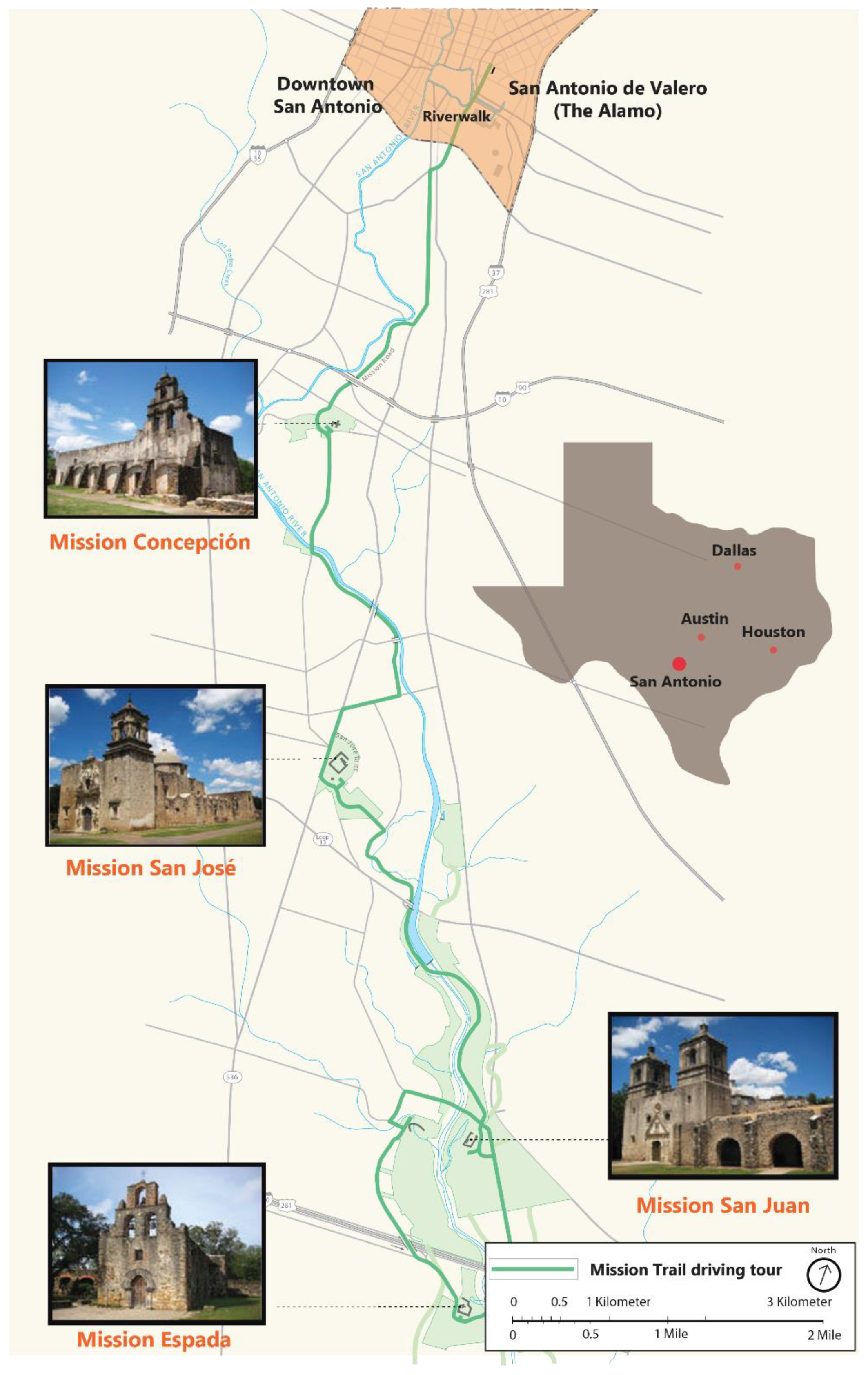

4.1. Site Selection

4.2. Data Collection

4.3. Research Instrument

4.4. Data Analysis

5. Findings

5.1. The Substance Dimension

5.1.1. History and Culture

5.1.2. Value and Interest

5.2. The Procedure Dimension

5.2.1. Formal Forms of Involvement

5.2.2. Informal Forms of Involvement

5.3. The Relationship Dimension

5.3.1. Attitude toward Park Management

5.3.2. Future Relationship

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Folke, C.; Carpenter, S.; Elmqvist, T.; Gunderson, L. Resilience and sustainable development: Building adaptive capacity in a world of transformations. Ambio 2002, 31, 437–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meffe, G.; Nielsen, L.; Knight, R.L.; Schenborn, D. Ecosystem Management: Adaptive, Community-Based Conservation; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-1559638241. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, R.B.; Vagias, W.M. The benefits of stakeholder involvement in the development of social science research. Park Sci. 2010, 27, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Berkes, F. Rethinking community-based conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2004, 18, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosius, J.P.; Russell, D. Conservation from above: An anthropological perspective on transboundary protected areas and ecoregional planning. J. Sustain. For. 2003, 17, 39–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K. Innovations for conservation and development. Geogr. J. 2002, 168, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilshusen, P.R.; Brechin, S.R.; Fortwangler, C.L.; West, P.C. Reinventing a square wheel: Critique of a resurgent “protection paradigm” in international biodiversity conservation. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2002, 15, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achana, F.T.; O’Leary, J.T. The transboundary relationship between national parks and adjacent communities. In National Parks and Rural Development: Practice and Policy in the United States; Machlis, G.E., Field, D.R., Eds.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; pp. 67–87. [Google Scholar]

- Fortin, M.J.; Gagnon, C. An assessment of social impacts of national parks on communities in Quebec, Canada. Environ. Conserv. 1999, 26, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, P.; Igoe, J.; Brockington, D. Parks and Peoples: The Social Impact of Protected Areas. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2006, 35, 251–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, M.A.; Anderson, D.H. Getting From Sense of Place to Place-Based Management: An Interpretive Investigation of Place Meanings and Perceptions of Landscape Change. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2005, 18, 625–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrod, B. Local participation in the planning and management of ecotourism: A revised model approach. J. Ecotour. 2003, 2, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative governance in theory and practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, H.D.; Barbuto, V.; Jonas, H.C.; Kothari, A.; Nelson, F. New steps of change: Looking beyond protected areas to consider other effective area-based conservation measures. Parks 2014, 20, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, S. Indigenous Peoples, National Parks, and Protected Areas: A New Paradigm Linking Conservation, Culture, and Rights; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2014; ISBN 0816530912. [Google Scholar]

- Esfehani, M.H.; Albrecht, J.N. Roles of intangible cultural heritage in tourism in natural protected areas. J. Herit. Tour. 2018, 13, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buta, N.; Holland, S.M.; Bustam, T.D. Residents’ interactions with and attachments to Retezat National Park, Romania: Implications for environmental responsibility. World Leis. J. 2014, 55, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šorgo, A.; Špur, N.; Škornik, S. Public attitudes and opinions as dimensions of efficient management with extensive meadows in Natura 2000 area. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 183, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutanga, C.N.; Vengesayi, S.; Muboko, N.; Gandiwa, E. Towards harmonious conservation relationships: A framework for understanding protected area staff-local community relationships in developing countries. J. Nat. Conserv. 2015, 25, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mombeshora, S.; Le Bel, S. Parks-people conflicts: The case of Gonarezhou National Park and the Chitsa community in south-east Zimbabwe. Biodivers. Conserv. 2009, 18, 2601–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougill, A.J.; Fraser, E.D.G.; Holden, J.; Hubacek, K.; Prell, C.; Reed, M.S.; Stringer, L.C. Learning from doing participatory rural research: Lessons from the Peak District National Park. J. Agric. Econ. 2006, 57, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremer, T.S. Inside the National Park. In Blessed with Tourists: The Borderlands of Religion and Tourism in San Antonio; Univ of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2004; pp. 117–146. ISBN 978-0-8078-5580-5. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, G.B. Conflict and the Challenges of Community-Based Collaboration: A Case Study of Oregon’s Illinois Valley; Oregon State University: Corvallis, OR, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, S.E.; Walker, G.B. Working through Environmental Conflict: The Collaborative Learning Approach; Praeger: Westport, CT, USA, 2001; ISBN 0275964736. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, A.; Lemos, M.C. A Greener Revolution in the Making?: Environmental Governance in the 21st Century. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 2007, 49, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunton, T.I.; Peter, T.; Day, J.C. Evaluating collaborative planning: A case study of a land and resource management planning process. Environments 2006, 34, 19–37. [Google Scholar]

- McGee, G.J. Evaluating Collaborative Planning: A Case Study of the North Coast Land and Resource Management Plan; Simon Fraser University: Burnaby, BC, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, A.; Gibson, C.C. Enchantment and disenchantment: The role of community in natural resource conservation. World Dev. 1999, 27, 629–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, C.G.; Luloff, A.E. Natural Resource-Based Communities, Risk, and Disaster: An Intersection of Theories. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2005, 18, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emborg, J.; Walker, G.; Daniels, S. Forest Landscape Restoration Decision-Making and Conflict Management: Applying Discourse-Based Approaches. In Forest Landscape Restoration; Stanturf, J., Lamb, D., Madsen, P., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 131–153. ISBN 978-94-007-5325-9. [Google Scholar]

- Borrini-Feyerabend, G.; Pimbert, M.; Farvar, M.T.; Kothari, A.; Renard, Y.; Jaireth, H.; Murphree, M.; Pattemore, V.; Warren, P. Sharing Power: Learning-By-Doing in Co-Management of Natural Resources throughout the World; Borrini, G., Ed.; Earthscan: Sterling, VA, USA, 2007; ISBN 1-84369-444-1. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, R.K.; Agle, B.R.; Wood, D.J. Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 853–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N. Equitable Gender Participation in Local Water Governance: An Insight into Institutional Paradoxes. Water Resour. Manag. 2008, 22, 925–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prell, C.; Reed, M.; Racin, L.; Hubacek, K. Competing structure, competing views: The role of formal and informal social structures in shaping stakeholder perceptions. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunasekaran, P.; Gill, S.S.; Ramachandran, S.; Shuib, A.; Baum, T.; Afandi, S.H.M. Measuring Sustainable Indigenous Tourism Indicators: A Case of Mah Meri Ethnic Group in Carey Island, Malaysia. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, C.G.; Luloff, A.E.; Finley, J.C. Where is “community” in community-based forestry? Soc. Nat. Resour. 2008, 21, 526–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G.B.; Daniels, S.E. Assessing the promise and potential for collaboration: The Progress Triangle framework. In Finding Our Way(s) in Environmental Communication: Proceedings of the Seventh Biennial Conference on Communication and the Environment, Silver Falls Conference Center, Sublimity, Oregon, 19–22 July 2003; Walker, G.B., Kinsella, W.J., Eds.; Oregon State University Department of Speech Communication: Corvallis, OR, USA, 2005; pp. 188–201. [Google Scholar]

- Keitumetse, S.O. Cultural resources as sustainability enablers: Towards a community-based cultural heritage resources management (COBACHREM) model. Sustainability 2013, 6, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruckmeier, K. Interdisciplinary conflict analysis and conflict mitigation in local resource management. Ambio 2005, 34, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCleave, J.; Espiner, S.; Booth, K. The New Zealand people-park relationship: An exploratory model. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2006, 19, 547–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, S.; Shwom, R.; Jordan, R. Understanding Factors That Influence Stakeholder Trust of Natural Resource Science and Institutions. Environ. Manag. 2012, 49, 669–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heemskerk, M.; Duijves, C.; Pinas, M. Interpersonal and institutional distrust as disabling factors in natural resources management: Small-scale gold miners and the government in Suriname. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2015, 28, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarrita-Cascante, D.; Zunino, H.; Sagner-Tapia, J. Amenity/lifestyle migration in the Chilean Andes: Understanding the views of “The other” and its effects on integrated community development. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkins, J.R.; Beckley, T.; Comeau, L.; Stedman, R.C.; Rollins, C.L.; Kessler, A. Can Distrust Enhance Public Engagement? Insights From a National Survey on Energy Issues in Canada. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2017, 30, 934–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ouyang, Z.; Miao, H. Environmental attitudes of stakeholders and their perceptions regarding protected area-community conflicts: A case study in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2010, 91, 2254–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito-Jensen, M.; Nathan, I. Exploring the Potentials of Community-Based Natural Resource Management for Benefiting Local Communities: Policies and Practice in Four Communities in Andhra Pradesh, India. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2011, 24, 1142–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Manning, R.; Perry, E.; Valliere, W. Public Awareness of and Visitation to National Parks by Racial/Ethnic Minorities. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2018, 31, 908–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ouyang, Z.; Miao, H. Environmental attitudes of stakeholders and their perceptions regarding protected area-community conflicts: A case study in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2010, 91, 2254–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wondolleck, J.M.; Yaffee, S.L. Making Collaboration Work: Lessons from Innovation in Natural Resource Managment; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; ISBN 1-55963-462-6. [Google Scholar]

- Hargrove, E. Foundations of Environmental Ethics. Available online: https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc52172/ (accessed on 8 October 2018).

- Stephens, B.; Wallace, C. Recreation, tourism and leisure through the lens of economics. In Leisure, Recreation and Tourism; Perkins, H.C., Cushman, G., Eds.; Longman Paul: Auckland, New Zealand, 1993; pp. 190–203. [Google Scholar]

- Payton, M.A.; Fulton, D.C.; Anderson, D.H. Influence of Place Attachment and Trust on Civic Action: A Study at Sherburne National Wildlife Refuge. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2005, 18, 511–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiallo, E.A.; Jacobson, S.K. Local Communities and Protected Areas: Attitudes of Rural Residents Towards Conservation and Machalilla National Park, Ecuador. Environ. Conserv. 1995, 22, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormsby, A.; Kaplin, B.A. A framework for understanding community resident perceptions of Masoala National Park, Madagascar. Environ. Conserv. 2005, 32, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doganer, S.; Dupont, W. Cultural heritage tourism and authenticity: San Antonio Missions Historic District. WIT Trans. Built Environ. 2013, 131, 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- National Park Service San Antonio Missions NHP NHP. Available online: http://www.nature.nps.gov/stats (accessed on 8 October 2018).

- Luyet, V.; Schlaepfer, R.; Parlange, M.B.; Buttler, A. A framework to implement stakeholder participation in environmental projects. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 111, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolcott, H. Transforming Qualitative Data: Description, Analysis, and Interpretation; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; ISBN 0-8039-5281-3. [Google Scholar]

- Guba, E.G.; Lincoln, Y.S. Fourth Generation Evaluation; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1989; ISBN 978-0803932357. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. An Introduction to Qualitative Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; ISBN 9781446267790. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. World Heritage List: San Antonio Franciscan Missions. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1466 (accessed on 16 February 2018).

- Doganer, S.; Dupont, W. Accelerating Cultural Heritage Tourism In San Antonio: A Community-based Tourism Development Proposal For The Missions Historic District. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2015, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehm, J.M.; Eisenhauer, B.W.; Stedman, R.C. Environmental Concern: Examining the Role of Place Meaning and Place Attachment. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2012, 26, 522–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.W.; Davenport, M.A.; Anderson, D.H.; Leahy, J.E. Place meanings and desired management outcomes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 101, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, E.A.; Thwaites, R.; Curtis, A.; Millar, J. Trust and trustworthiness: Conceptual distinctions and their implications for natural resources management. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2013, 56, 1246–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarrita-Cascante, D. Moving the amenity migration literature forward: Understanding community-level factors associated with positive outcomes after amenity-driven change. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 53, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, G.; Matarrita-Cascante, D.; Fernanda Rodriguez, M. International amenity migration: Implications for integrated community development opportunities. Community Dev. 2014, 45, 507–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Topic | Questions |

|---|---|

| Substance | What do the San Antonio Missions mean to you? How would you characterize them? In what way(s) do you use the San Antonio Missions? Think of any type of activity that you perform in or related to the missions and how often you engage in those. |

| Procedure | Are you actively involved in any effort to improve the San Antonio Missions? If yes, what kind of efforts and with whom? |

| Relationship | What is your relationship with San Antonio Mission’s park management or any group that is related or interested in the San Antonio Missions in this community? Has this relationship(s) changed over time? Where do you see this relationship going in the future? How would you like the future of the San Antonio Missions to be? |

| Respondent | Substance | Procedure | Relationship | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History and Culture | Values and Interests | Formal Forms of Involvement | Informal Forms of Involvement | Attitude Toward the Park Management | Future Relationship | |

| Respondent 1 (Native American) | Family history (History of our ancestors) | Roots of our family Spiritual connection with our ancestors | Uninterested about World Heritage designation | Fundraising (e.g., Father David’s group) | Negative relationship Lack of culture of community They are trying to erase Indian culture | No changes would be made |

| Respondent n | ||||||

| Stakeholder | History and Culture | Values and Interests |

|---|---|---|

| Native Americans | The history of Native Americans | The honoring of their ancestors |

| Non-native locals | A blend of Spanish, Mexican, and Native American history and culture | The promotion of a sense of community |

| Members of a friends-of-the-park (FoP) group | Historical monuments that show the past of the city of San Antonio | Educational values for locals and visitors |

| Representatives of the local government and public agencies | The origins of the city of San Antonio | Economic values for the community |

| Stakeholder | Formal Forms of Involvement | Informal Forms of Involvement |

|---|---|---|

| Native Americans | They were the least involved in the World Heritage (WH) project. | Most were involved in improvement of the church cemeteries. |

| Non-native locals | Only a few locals were engaged in the WH project. | A few were involved in maintenance of mission areas (e.g., cleaning the road, fundraising events). |

| Members of an FoP group | An official chartered FoP group played a key role in restoration of the four churches in the missions. | Unofficial FoP groups (e.g., San Jose Neighborhood Association) were involved in fundraising events and volunteering activities. |

| Representatives of the local government and public agencies | Members actively worked with the National Park Service (NPS) for the nomination of WH site. | Volunteer work or fundraising activities were not reported. |

| Stakeholder | Attitude Toward the Park Management | Future Relationship |

|---|---|---|

| Native Americans | Negative relationship: There was considerable suspicion and mistrust toward federal government. | Same or negative: Pessimistic about their future relationship with the NPS. |

| Non-native locals | Neutral relationship: Most of them had no interaction with park staff. | No intention to form relationship: Despite their interests about development, no intention to form relationships with park staff was reported. |

| Members of an FoP group | Supportive relationship: For preservation and restoration of the missions, they supported and respected park management. | Desired a different relationship with the NPS: They believe that collaboration work with the NPS should be continued to preserve cultural heritage rather than to encourage commercial development. |

| Representatives of the local government and public agencies | Beneficial relationship: Collaboratively worked in union and harmony for the WH nomination by supporting and funding the NPS. | Expected better and stronger relationship: They expected continuous economic development of the missions for the WH designation. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, J.H.; Matarrita-Cascante, D.; Xu, Y.; Schuett, M. Examining the Conflicting Relationship between U.S. National Parks and Host Communities: Understanding a Community’s Diverging Perspectives. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3667. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103667

Lee JH, Matarrita-Cascante D, Xu Y, Schuett M. Examining the Conflicting Relationship between U.S. National Parks and Host Communities: Understanding a Community’s Diverging Perspectives. Sustainability. 2018; 10(10):3667. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103667

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Jae Ho, David Matarrita-Cascante, Ying Xu, and Michael Schuett. 2018. "Examining the Conflicting Relationship between U.S. National Parks and Host Communities: Understanding a Community’s Diverging Perspectives" Sustainability 10, no. 10: 3667. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103667

APA StyleLee, J. H., Matarrita-Cascante, D., Xu, Y., & Schuett, M. (2018). Examining the Conflicting Relationship between U.S. National Parks and Host Communities: Understanding a Community’s Diverging Perspectives. Sustainability, 10(10), 3667. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103667