Tourism as an Approach to Sustainable Rural Development in Post-Socialist Countries: A Comparative Study of Serbia and Slovenia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. An Overview on Rural Tourism in Transitional Societies

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis Findings

4.2. Statistical Correlation Findings

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Horakova, H. Post-Communist Transformation of Tourism in Czech Rural Areas: New Dilemmas. Anthropol. Noteb. 2010, 16, 59–77. [Google Scholar]

- Leanza, P.; Porto, S.; Sapienza, V.; Cascone, S.A. Heritage Interpretation-Based Itinerary to Enhance Tourist Use of Traditional Rural Buildings. Sustainability 2016, 8, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilbao-Terol, C.; Cañal-Fernández, V.; Valdés, L.; Del Valle, E. Rural Tourism Accommodation Prices by Land Use-Based Hedonic Approach: First Results from the Case Study of the Self-Catering Cottages in Asturias. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Sustainable Development Strategy (Serbia). 2007. Available online: http://www.un.org/esa/agenda21/natlinfo/countr/serbia/nsds_serbia.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2017).

- Petrović, M.D.; Blešić, I.; Ivolga, A.; Vujko, A. Agritourism Impact toward Locals’ Attitudes—An Evidence from Vojvodina Province (Serbia). J. Geogr. Inst. Jovan Cvijić SASA 2016, 66, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koscak, M. Integral Development of Rural Areas, Tourism and Village Renovation, Trebnje, Slovenia. Tour. Manag. 1998, 19, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erjavec, E.; Rednak, M.; Volk, T. The European Union enlargement—The case of agriculture in Slovenia. Food Policy 1998, 23, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knežević, A.A.; Cvelbar, L.J. Privatization, Market Competition, International Attractiveness, Management Tenure and Hotel Performance: Evidence from Slovenia. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lock, K.; Gabrijelcic-Blenkus, M.; Martuzzi, M.; Otorepec, P.; Kuhar, A.; Robertson, A.; Wallace, E.; Dora, C.; Maucec Zakotnic, J. Conducting an HIA of the Effect of Accession to the European Union on National Agriculture and Food Policy in Slovenia. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2004, 24, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L.; Knežević Cvelbar, L.J.; Edwards, D.; Mihalič, T. Fashioning a Destination Tourism Future: The Case of Slovenia. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estol, J.; Font, X. European Tourism Policy: Its Evolution and Structure. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenski, T.; Gomezelj, D.; Djurdjev, B.; Ćurčić, N.; Dragin, A. Tourism Destination Competitiveness—Between Two Flags. Econ. Res. Ekon. Istraž. 2012, 25, 485–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potočnik-Slavič, I.; Schmitz, S. Farm Tourism across Europe. Eur. Countrys. 2013, 4, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, S.; Aitchison, C. The Role of Gastronomy Tourism in Sustaining Regional Identity: A Case Study of Cornwall, South West England. J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursache, M. Tourism—Significant Driver Shaping a Destinations Heritage. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 188, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirović, D.; Petrović, M.D.; Neto Monteiro, L.C.; Stjepanović, S. An Examination of Competitiveness of Rural Tourism Destinations from the Supply Side Perspective—Case of Vojvodina (Serbia). J. Geogr. Inst. Jovan Cvijić SASA 2016, 66, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, M.D.; Lukić, D.; Radovanović, M.; Vujko, A.; Gajić, T.; Vuković, D. “Urban geosites” as potential geotourism destinations—Evidence from Belgrade. Open Geosci. 2017, 9, 442–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komppula, R. The Role of Individual Entrepreneurs in the Development of Competitiveness for a Rural Tourism Destination—A Case Study. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva-Álvaro, J.; Mondéjar-Jiménez, J.; Sáez-Martínez, F. Rural Tourism: Development, Management and Sustainability in Rural Establishments. Sustainability 2017, 9, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campón-Cerro, A.; Folgado-Fernández, J.; Hernández-Mogollón, J. Rural Destination Development Based on Olive Oil Tourism: The Impact of Residents’ Community Attachment and Quality of Life on Their Support for Tourism Development. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L.; Kim, C. Destination Competitiveness: Determinants and Indicators. Curr. Issues Tour. 2003, 6, 369–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, B.; Kastenholz, E. Rural tourism: The evolution of practice and research approaches—Towards a new generation concept? J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1133–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.; Fesenmaier, D.R.; Fesenmaier, J.; Van Es, J.C. Factors for success in rural tourism development. J. Travel Res. 2001, 40, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D. Rural tourism development in southeastern Europe: Transition and the search for sustainability. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2004, 6, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R. Rural tourism and the challenge of tourism diversification: The case of Cyprus. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrick, M.; Gramzow, A. Harnessing Communities, Markets and the State for Public Goods Provision: Evidence from Post-Socialist Rural Poland. World Dev. 2012, 40, 2342–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulcak, F.; Haider, J.L.; Abson, D.J.; Newig, J.; Fischer, J. Applying a Capitals Approach to Understand Rural Development Traps: A Case Study from Post-Socialist Romania. Land Use Policy 2015, 43, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, M.D.; Blešić, I.; Vujko, A.; Gajić, T. The Role of Agritourism’s Impact on the Local Community in a Transitional Society: A Report from Serbia. Transylv. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2017, 13, 146–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, M.D.; Gelbman, A.; Demirović, D.; Gagić, S.; Vuković, D. The Examination of the Residents’ Activities and Dedication to the Local Community—An Agritourism Access to the Subject. J. Geogr. Inst. Jovan Cvijić SASA 2017, 67, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, D. ‘Facing the Future’: Tourism and Identity-Building in Post-Socialist Romania. Political Geogr. 2001, 20, 1053–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.A.; Balaž, V. The Czech and Slovak Republics: Conceptual Issues in the Economic Analysis of Tourism in Transition. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrschel, T. Between Difference and Adjustment—The Re-/Presentation and Implementation of Post-Socialist (Communist) Transformation. Geoforum 2007, 38, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Săvoiu, G.; Ţaicu, M. Foreign Direct Investment Models, Based on Country Risk for Some Post-Socialist Central and Eastern European Economies. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2014, 10, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeković, S.; Vujošević, M.; Maričić, T. Spatial Regularization, Planning Instruments and Urban Land Market in a Post-Socialist Society: The Case of Belgrade. Habitat Int. 2015, 48, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujko, A.; Gajić, T. Opportunities for Tourism Development and Cooperation in the Region by improving the Quality of Supply—The “Danube Cycle Route” Case Study. Econ. Res. Ekon. Istraž. 2014, 27, 847–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaine, T.W.; Mohammad, G.; Var, T. Demand for Rural Tourism: An Exploratory Study. Ann. Tour. Res. 1993, 20, 770–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sznajder, M.; Przezbórska, L.; Scrimgeour, F. Agritourism; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Todorović, М.; Bjeljac, Ž. Rural Tourism in Serbia as a Concept of Development in Undeveloped Regions. Acta Geogr. Slov. 2009, 49, 453–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EuroGites—European Federation of Rural Tourism. Available online: http://eurogites.org/documents/ (accessed on 16 December 2017).

- Knickel, K.; Renting, H. Methodological and Conceptual Issues in the Study of Multifunctionality and Rural Development. Sociol. Rural. 2000, 40, 512–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohe, Y. Multifunctionality and rural tourism: A perspective on farm diversification. J. Int. Farm Manag. 2007, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Petrović, M.D.; Radović, G.; Terzić, A. An Overview of Agritourism Development in Serbia and European Union Countries. Int. J. Sustain. Econ. Manag. (IJSEM) 2015, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L.; Mellor, R.; Livaic, Z.; Edwards, D.; Kim, C.W. Attributes of Destination Competitiveness: A Factor Analysis. Tour. Anal. 2004, 9, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomezelj, O.D.; Mihalič, T. Destination Competitiveness—Applying Different Models, the Case of Slovenia. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 294–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragićević, V.; Jovičić, D.; Blešić, I.; Stankov, U.; Bošković, D. Business Tourism Destination Competitiveness: A Case of Vojvodina Province (Serbia). Econ. Res. Ekon. Istraž. 2012, 25, 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, C.H.; Lo, M.C.; Songan, P.; Nair, V. Rural Tourism Destination Competitiveness: A Study on Annah Rais Longhouse Homestay, Sarawak. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 144, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulec, I.; Wise, N. Indicating the Competitiveness of Serbia’s Vojvodina Region as an Emerging Tourism Destination. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 8, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujko, A.; Petrović, M.D.; Dragosavac, M.; Gajić, T. Differences and Similarities among Rural Tourism in Slovenia and Serbia—Perceptions of Local Tourism Workers. Ekon. Poljopr. Econ. Agric. 2016, 63, 1459–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

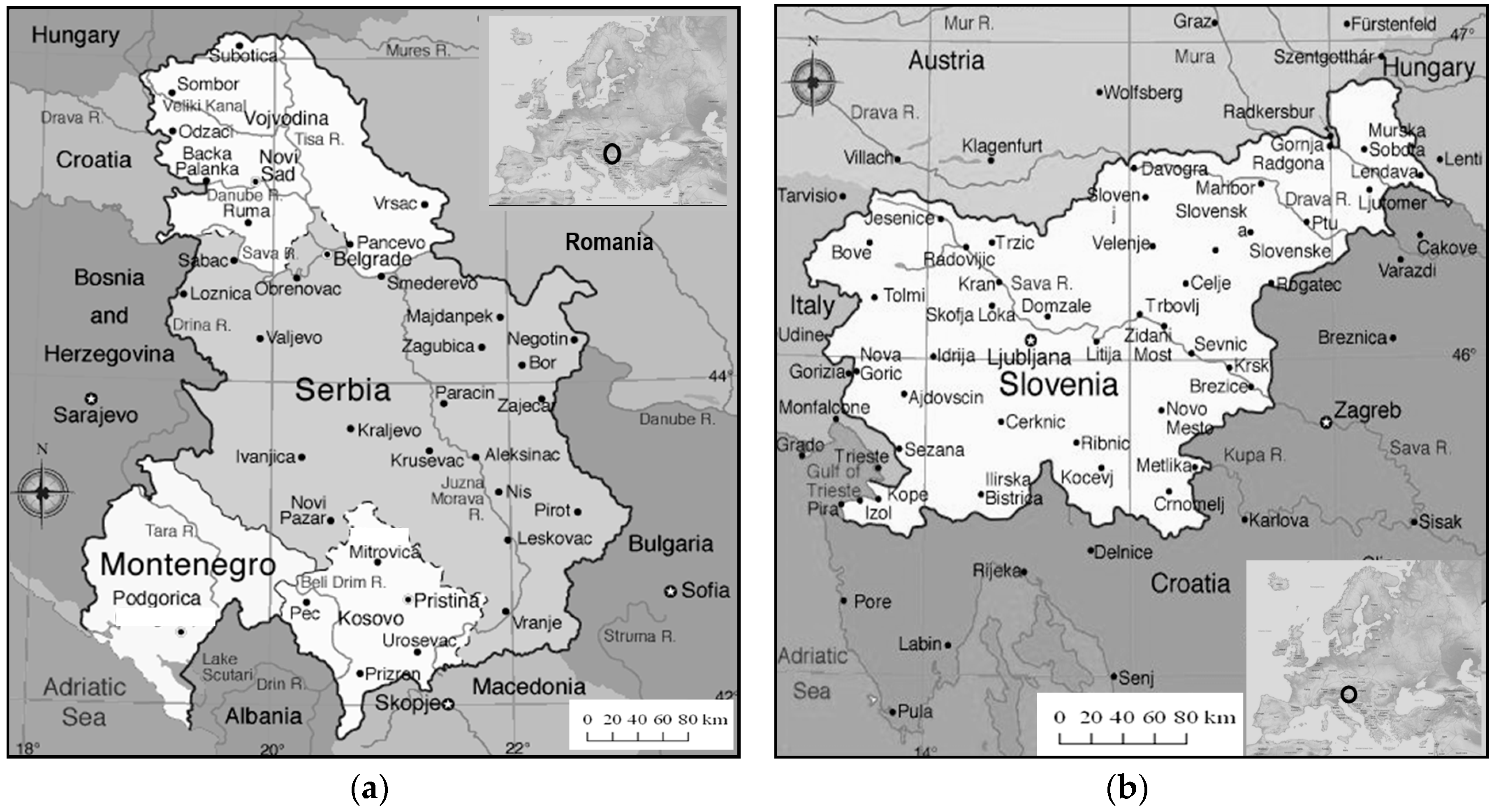

- Magellan Geographix. Available online: https://www.pinterest.com/geographylovin/europe-geography/ (accessed on 22 November 2017).

- Rey, V.; Groza, O. Balkans. In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography; Kitchin, R., Thrift, N., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 265–272. [Google Scholar]

- Grum, B.; Kobal Grum, D. Satisfaction with Current Residence Status in Comparison with Expectations of Real Estate Buyers in Slovenia and Serbia. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 109, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia (SORS, 2017). Available online: http://www.stat.gov.rs/website/public/pageview.aspx?pkey=180 (accessed on 30 May 2017).

- Statistical Office of Slovenia (SURS, 2017). Available online: http://pxweb.stat.si/pxweb/database/economy/economy.asp (accessed on 2 June 2017).

- Šprah, L.; Novak, T.; Fridl, J. The Wellbeing of Slovenia’s Population by Region: Comparison of Indicators with an Emphasis on Health. Acta Geogr. Slov. 2014, 54, 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R.D. Tourism Development and Sustainability Issues in Central and South-Eastern Europe. Tour. Manag. 1998, 19, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cracolici, M.F.; Nijkamp, P. The attractiveness and competitiveness of tourist destinations: A study of Southern Italian Regions. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.R.B.; Crouch, G.I. The Competitive Destination. A Sustainable Tourism Perspective; CABI Publishing: Oxon, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Woosnam, K.M. Using Emotional Solidarity to explain residents’ attitudes about tourism and tourism development. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Respondent from Serbia | f | % |

| Members of National Association “Rural Tourism of Serbia” | 46 | 22.0 |

| Members of Business Association of Hotel and Restaurant Industry in Serbia | 47 | 22.5 |

| Managers and employees from six traditional farmsteads (Dida Hornjakov salaš near Sombor, Salaš 137 in Čenej, Majkin salaš in Palić, Katai salaš in Mali Idjoš, Cvejin salaš in Begeč and Perkov salaš near Neradin) | 37 | 17.7 |

| Managers and employees from Panacomp Rural Hospitality Net and Magelan Travel Agency | 9 | 4.3 |

| Members of Association “UGONS 1946” | 29 | 13.9 |

| Members of Association of Tourists Guides of City of Novi Sad | 41 | 19.6 |

| Total | 209 | 100 |

| Type of Respondent from Slovenia | f | % |

| Members of Slovenian Tourist Guides | 27 | 20.3 |

| Members of Association of Tourists Agencies of Slovenia | 32 | 24.1 |

| Members of National Tourists Association—NTA | 42 | 31.6 |

| Members of International Tourism Institute and Association of Tourists Farms of Slovenia | 32 | 24.1 |

| Total | 133 | 100 |

| Serbia n = 209 | Slovenia n = 133 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| f | % | f | % | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 111 | 53.1 | 78 | 58.6 |

| Female | 98 | 46.9 | 55 | 41.4 |

| Age | ||||

| 15–24 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3.0 |

| 25–34 | 37 | 17.7 | 4 | 3.0 |

| 35–44 | 102 | 48.8 | 59 | 44.4 |

| 45–54 | 62 | 29.7 | 61 | 45.9 |

| 55–64 | 6 | 2.9 | 3 | 2.3 |

| >65 | 2 | 1.0 | 2 | 1.5 |

| Educational level | ||||

| Elementary school | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| High school | 34 | 16.3 | 1 | 0.8 |

| College | 97 | 46.4 | 69 | 51.9 |

| Faculty | 65 | 31.1 | 52 | 39.1 |

| M.Sc./Ph.D. studies | 13 | 6.2 | 11 | 8.3 |

| Average monthly income | ||||

| <200 € | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 201–500 € | 135 | 64.6 | 0 | 0 |

| 501–1000 € | 18 | 8.6 | 2 | 1.5 |

| >1001 € | 0 | 0 | 100 | 75.2 |

| Incomplete responses | 56 | 26.8 | 31 | 23.3 |

| Profession | ||||

| Student | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Full time job | 185 | 88.5 | 133 | 100 |

| Part time job | 24 | 11.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Retired | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Components | Serbia | Slovenia |

|---|---|---|

| Rural area (% of the total territory) | 85% | 90% |

| Rural population (% of the total population) | 48% | 57% |

| Population density in rural areas (inhabitants/km2) | 84 | 102 |

| Mean unemployment rate in rural areas | 21% | 9% |

| Number of households offering tourism services | 300 | 600 |

| Mean annual number of overnight stays | 150,000 | 300,000 |

| Mean length of stay (days) | 2.8 | 3.7 |

| Total accommodation capacities (number of beds) | 8000 | 6000 |

| Mean utilization of capacities | 40% | 70% |

| Mean profit per a household (annual in Euros) | 2500 | 10,000 |

| Competitiveness Indicators | Serbia | Slovenia | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| SF1 | Friendliness of residents towards tourists. | 3.35 | 0.819 | 4.21 | 0.970 |

| SF2 | Distance/flying time to destination. | 3.84 | 0.686 | 4.10 | 0.912 |

| SF3 | Ease of communication between residents and tourists. | 4.52 | 0.589 | 4.44 | 0.899 |

| SF4 | Financial institution and currency exchange facilities. | 2.09 | 0.761 | 3.51 | 0.974 |

| SF5 | Telecommunication system. | 3.84 | 0.748 | 4.92 | 0.471 |

| SF6 | Resident support for the tourism industry. | 2.24 | 0.658 | 4.70 | 0.603 |

| SF7 | Ease/cost of obtaining entry Visa. | 2.48 | 0.760 | 4.32 | 0.744 |

| SF8 | Ethnic ties with major tourist origin markets. | 2.93 | 0.690 | 4.53 | 0.774 |

| SF9 | Ease of combining travel to destination. | 4.19 | 0.611 | 4.30 | 0.738 |

| SF10 | Awareness of tourism employees about quality of services. | 3.42 | 0.743 | 4.67 | 0.660 |

| SF11 | Sporting links with major tourist origin markets. | 2.93 | 0.784 | 4.38 | 0.725 |

| SF12 | Health/medical facilities to serve tourists. | 4.10 | 0.567 | 4.29 | 0.734 |

| SF13 | Business ties/trade links with major tourist origin markets. | 2.44 | 0.625 | 3.89 | 0.794 |

| SF14 | Tourism companies have programs to ensure/monitor visitors’ satisfaction. | 3.35 | 0.909 | 4.52 | 0.670 |

| SF15 | Adequacy of infrastructure. | 2.31 | 0.652 | 4.64 | 0.620 |

| SF16 | Local transport systems. | 1.93 | 0.744 | 4.37 | 0.764 |

| SF17 | Existence of resident hospitality development programs. | 3.29 | 0.885 | 4.49 | 0.745 |

| SF18 | Development of training programs to enhance quality of service. | 2.83 | 0.609 | 4.58 | 0.809 |

| SF19 | Waste disposal. | 2.08 | 0.817 | 3.72 | 0.932 |

| SF20 | Tourism/hospitality companies have well defined performance standards. | 1.99 | 0.658 | 4.08 | 0.785 |

| Competitiveness Indicators | Serbia | Slovenia | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| DF1 | Overall perception of country as a tourism destination. | 4.16 | 0.548 | 4.65 | 0.618 |

| DF2 | Destination awareness. | 3.92 | 0.678 | 4.53 | 0.634 |

| DF3 | Awareness of tourism products of country abroad. | 4.18 | 0.530 | 4.84 | 0.534 |

| DF4 | Destination image and perception in the world. | 2.39 | 0.700 | 4.78 | 0.569 |

| DF1 | DF2 | DF3 | DF4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRB | SLO | SRB | SLO | SRB | SLO | SRB | SLO | |

| SF1 | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.24 | 0.44 | 0.24 | 0.44 | 0.52 | 0.66 |

| SF2 | 0.67 | 0.71 | 0.28 | 0.39 | 0.28 | 0.39 | 0.22 | 0.31 |

| SF3 | 0.72 | 0.79 | 0.88 | 0.92 | 0.88 | 0.92 | 0.21 | 0.23 |

| SF4 | 0.33 | 0.41 | 0.24 | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.27 | 0.21 | 0.44 |

| SF5 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.14 | 0.29 | 0.14 | 0.29 | 0.48 | 0.49 |

| SF6 | 0.77 | 0.83 | 0.21 | 0.44 | 0.21 | 0.44 | 0.21 | 0.28 |

| SF7 | 0.10 | 0.24 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.22 |

| SF8 | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.11 | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.31 | 0.52 | 0.81 |

| SF9 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.54 | 0.66 | 0.54 | 0.66 | 0.24 | 0.31 |

| SF10 | 0.31 | 0.36 | 0.25 | 0.41 | 0.25 | 0.41 | 0.11 | 0.23 |

| SF11 | 0.14 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.44 | 0.21 | 0.44 | 0.25 | 0.44 |

| SF12 | 0.71 | 0.92 | 0.14 | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.24 |

| SF13 | 0.43 | 0.48 | 0.72 | 0.76 | 0.72 | 0.76 | 0.26 | 0.26 |

| SF14 | 0.24 | 0.27 | 0.21 | 0.31 | 0.21 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.35 |

| SF15 | 0.78 | 0.86 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.28 | 0.36 |

| SF16 | 0.63 | 0.74 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.22 |

| SF17 | 0.33 | 0.43 | 0.21 | 0.44 | 0.21 | 0.44 | 0.20 | 0.29 |

| SF18 | 0.21 | 0.35 | 0.18 | 0.24 | 0.18 | 0.24 | 0.33 | 0.46 |

| SF19 | 0.52 | 0.53 | 0.24 | 0.33 | 0.24 | 0.33 | 0.17 | 0.21 |

| SF20 | 0.61 | 0.66 | 0.68 | 0.77 | 0.68 | 0.77 | 0.81 | 0.82 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Petrović, M.D.; Vujko, A.; Gajić, T.; Vuković, D.B.; Radovanović, M.; Jovanović, J.M.; Vuković, N. Tourism as an Approach to Sustainable Rural Development in Post-Socialist Countries: A Comparative Study of Serbia and Slovenia. Sustainability 2018, 10, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10010054

Petrović MD, Vujko A, Gajić T, Vuković DB, Radovanović M, Jovanović JM, Vuković N. Tourism as an Approach to Sustainable Rural Development in Post-Socialist Countries: A Comparative Study of Serbia and Slovenia. Sustainability. 2018; 10(1):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10010054

Chicago/Turabian StylePetrović, Marko D., Aleksandra Vujko, Tamara Gajić, Darko B. Vuković, Milan Radovanović, Jasmina M. Jovanović, and Natalia Vuković. 2018. "Tourism as an Approach to Sustainable Rural Development in Post-Socialist Countries: A Comparative Study of Serbia and Slovenia" Sustainability 10, no. 1: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10010054

APA StylePetrović, M. D., Vujko, A., Gajić, T., Vuković, D. B., Radovanović, M., Jovanović, J. M., & Vuković, N. (2018). Tourism as an Approach to Sustainable Rural Development in Post-Socialist Countries: A Comparative Study of Serbia and Slovenia. Sustainability, 10(1), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10010054