Informal Land Development on the Urban Fringe

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Evolution of Land Development in China

2.1. Formal Land Development

2.2. Informal Land Development

2.3. The Coexistence of Multiple Land Development Modes

3. Data and Methods

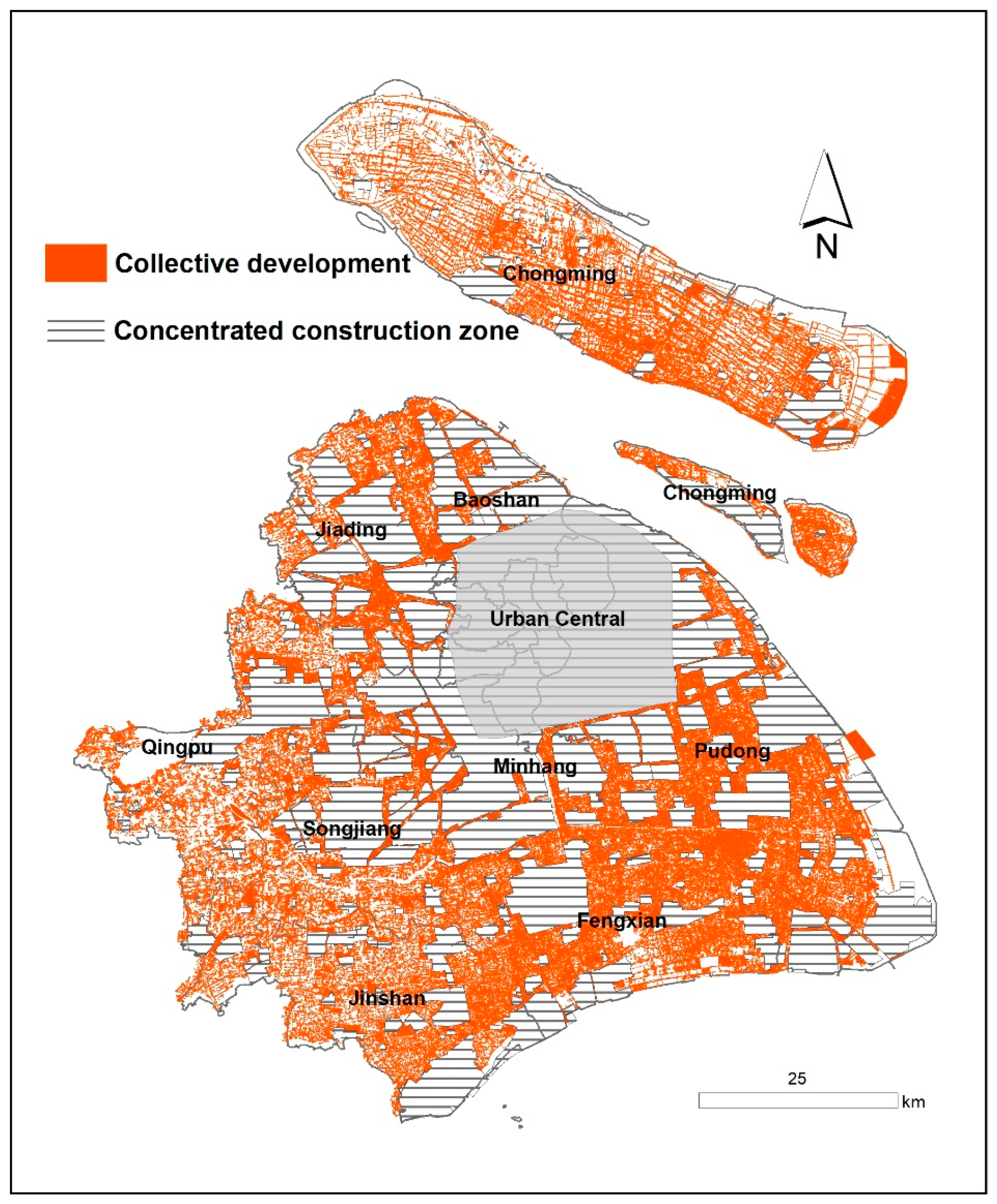

3.1. Urban Fringe in Shanghai

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Informal Modes of Land Development

4.1. Mode I: Village Collectives Act as Principal Agents and Property Is Developed Only for Rent

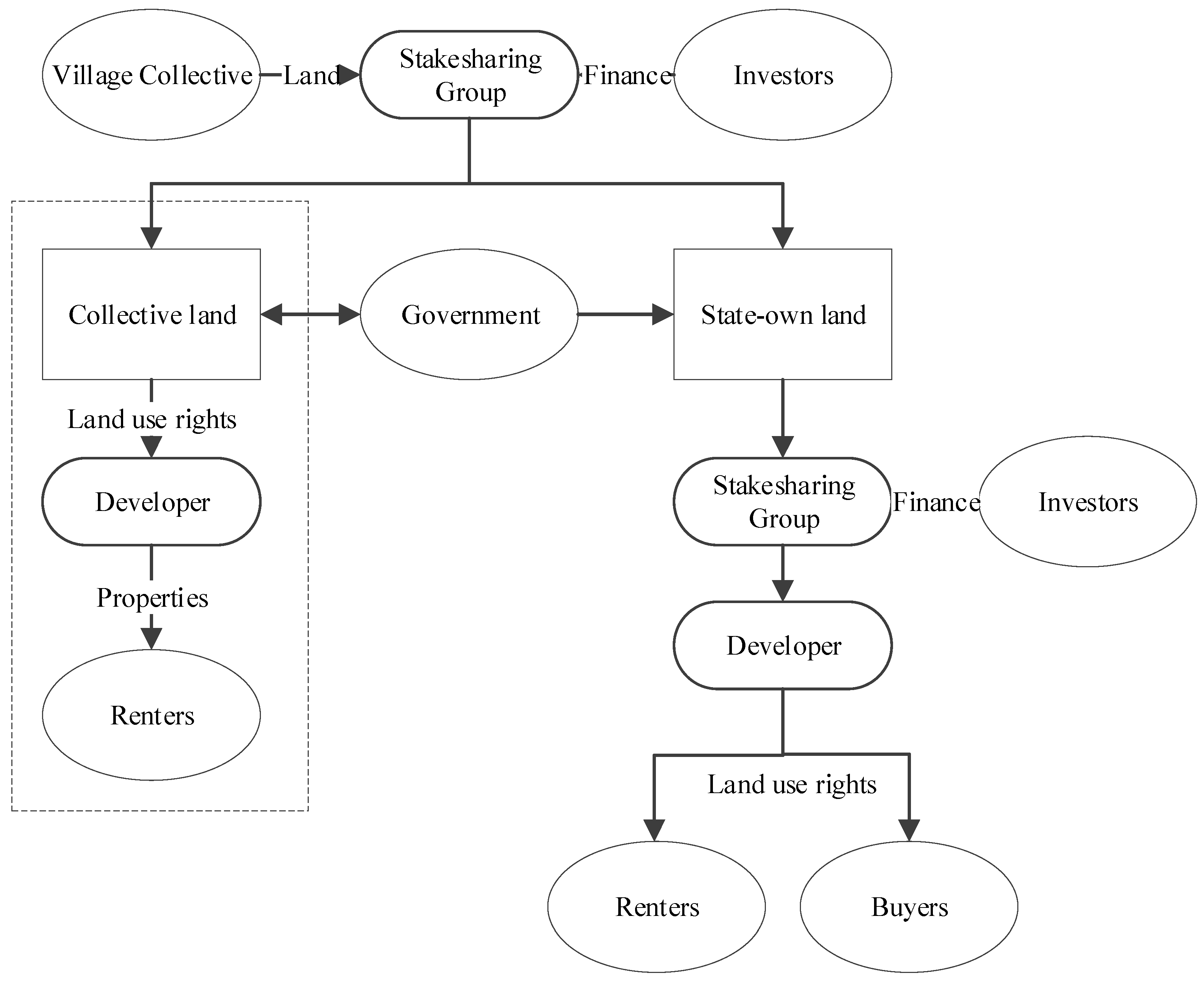

4.1.1. Structure

4.1.2. Operating Mechanism

4.1.3. The Problem

4.1.4. Case Analysis: Minhang Jiuxing and the Jiuxing Market

4.2. Mode II: Land Developers, Village Collectives, and Third-Party Enterprises Are Primary Joint Developers

4.2.1. Structure

4.2.2. The Operating Mechanism

4.2.3. The Problem

4.2.4. Case Analysis: Putuo Xinyang Industrial Zone

4.3. Mode III: Piloting of Collective Construction Land Transfers

4.3.1. Structure

4.3.2. Operating Mechanisms

4.3.3. The Problem

4.3.4. Case Analysis: Pudong Yimin

4.4. Mode IV: Piloting of Expropriation of Land Rights and Retention of Land Use Rights

4.4.1. Structure

4.4.2. Operating Mechanism

4.4.3. The Problem

4.4.4. Case Analysis: Hongqiao

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bryant, C.R.; Russwurm, L.; McLellan, A.G. The City’s Countryside. Land and Its Management in the Rural-Urban Fringe; Longman: Harlow, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Pryor, R.J. Defining the Rural-urban Fringe. Soc. Forces 1968, 47, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuo, A.D.M. Exploring Land Development Dynamics in Rural-Urban Fringes: A Reflection on Why Agriculture is Being Squeezed Out by Urban Land Uses in the Nairobi Rural–Urban Fringe? Int. J. Rural Manag. 2013, 9, 105–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.W. Cities Inside Out: Race, Poverty, and Exclusion at the Urban Fringe. UCLA Rev. 2007, 55, 1095–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.; Carter, C.; Reed, M.; Larkham, P.; Adams, D.; Morton, N.; Waters, R.; Collier, D.; Crean, C.; Curzon, R.; et al. Disintegrated Development at the Rural–urban Fringe: Re-connecting Spatial Planning Theory and Practice. Prog. Plan. 2013, 83, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F. China’s Changing Urban Governance in the Transition Towards a More Market-oriented Economy. Urban Stud. 2002, 39, 1071–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P. Sustainable Urban Expansion and Transportation in a Growing Megacity: Consequences of Urban Sprawl for Mobility on the Urban Fringe of Beijing. Habitat Int. 2010, 34, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.R.; Toll, D.L. Detecting Residential Land use Development at the Urban Fringe. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 1982, 48, 629–643. [Google Scholar]

- López, E.; Bocco, G.; Mendoza, M.; Duhau, E. Predicting Land-cover and Land use Change in the Urban Fringe: A Case in Morelia City, Mexico. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2001, 55, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.C. Reproducing Spaces of Chinese Urbanisation: New City-based and Land-centred Urban Transformation. Urban Stud. 2007, 44, 1827–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W. The Changing Dynamics of Land use Change in Rural China: A Case Study of Yuhang, Zhejiang Province. Environ. Plan. A 2004, 36, 1595–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y. In Situ Urbanization in Rural China: Case Studies from Fujian Province. Dev. Chang. 2000, 31, 413–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y. Beyond Large-city-centred Urbanisation: In-Situ Transformationof Rural Areas in Fujian Province. Asia Pac. Viewp. 2002, 43, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perotti, E.C.; Sun, L.; Zou, L. State-Owned versus Township and Village Enterprises in China. In China’s Economic Development; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 33–59. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.L. China’s Town and Village Enterprises and Its Implications for Sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Technol. Glob. 2015, 8, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.P.; Wang, Y.; Wu, J. Urbanization and Informal Development in China: Urban Villages in Shenzhen. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2009, 33, 957–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J. From Land Use Rights to Land Development Rights: Institutional Change in China’s Urban Development. Urban Stud. 2004, 41, 1249–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.C. Understanding Land Development Problems in Globalizing China. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2010, 51, 80–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, R.; Xu, W. Modes of Land Development in Shanghai. Land Use Policy 2017, 61, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaubatz, P. China’s Urban Transformation: Patterns and Processes of Morphological Change in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou. Urban Stud. 1999, 36, 1495–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Tan, K. Impact of Reform and Economic Restructuring on Rural Systems in China: A Case Study of Yuhang, Zhejiang. J. Rural Stud. 2002, 18, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, A.G.-O.; Li, X. Economic Development and Agricultural Land Loss in the Pearl River Delta, China. Habitat Int. 1999, 23, 373–390. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X. Urban Land Reform in China. Land Use Policy 1997, 14, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, A.G.-O.; Wu, F. The New Land Development Process and Urban Development in Chinese Cities. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 1996, 20, 330–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C. Land Policy Reform in China: Assessment and Prospects. Land Use Policy 2003, 20, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowall, D.E. Establishing urban land markets in the People’s Republic of China. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1993, 59, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C. Urban Spatial Development in the Land Policy Reform Era: Evidence from Beijing. Urban Stud. 2004, 41, 1889–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.C.; Ho, S.P. The State, Land System, and Land Development Processes in Contemporary China. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2005, 95, 411–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Ma, W. Government Intervention in City Development of China: A Tool of Land Supply. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F. The Role of Government and Farmers in Land Development and Transfer. Sociol. Stud. 2007, 1, 49–82. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, G.C. Developing China: Land, Politics and Social Conditions; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; Tan, K. Reform and the Process of Economic Restructuring in Rural China: A Case Study of Yuhang, Zhejiang. J. Rural Stud. 2001, 17, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.J.; Fan, M. Urbanisation from Below: The Growth of Towns in Jiangsu, China. Urban Stud. 1994, 31, 1625–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.R. Who Will Feed China; World Watch Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, C.; Lichtenberg, E. Land and Urban Economic Growth in China. J. Reg. Sci. 2011, 51, 299–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.; Zhao, X. The Influence of Bureaucratic Behavior on Land Apportionment in China: The Informal Process. Environ. Plan. C 1999, 17, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Zhao, X. Land market, land development and urban spatial structure in Beijing. Land Use Policy 2014, 40, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Thill, J.-C.; Peiser, R.B.; Feng, C. Urban land market and land use changes in post-reform China: A case study of Beijing. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 124, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.C.; Li, X.; Yang, F.F.; Hu, F.Z. Strategizing Urbanism in the Era of Neoliberalization: State Power Reshuffling, Land Development and Municipal Finance in Urbanizing China. Urban Stud. 2014, 52, 1962–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coase, R.; Wang, N. How China Became Capitalist; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F. Planning for Growth: Urban and Regional Planning in China; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, G.; Gao, J.; Liu, Y. Solving the Problem of “Agriculture, Farmer, and Rural Area” by Rule of Law; Hamilton Books; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Waley, P.; Gonzalez, S. Shanghai swings: The Hongqiao project and competitive urbanism in the Yangtze River Delta. Environ. Plan. A 2016, 48, 1928–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F. China’s Recent Urban Development in the Process of Land and Housing Marketisation and Economic Globalisation. Habitat Int. 2001, 25, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Zhang, J. Planning the Competitive City-region the Emergence of Strategic Development Plan in China. Urban Aff. Rev. 2007, 42, 714–740. [Google Scholar]

| Aspect | Elements |

|---|---|

| Land Source | State-owned |

| Collective-owned | |

| Both | |

| Main Agent | Government |

| Collective | |

| Developer | |

| Others | |

| Method of Land Acquisition | Rent |

| Expropriation | |

| Transaction | |

| Expropriation retention | |

| Infrastructure | Government |

| Collective | |

| Developer | |

| Enterprise | |

| Other | |

| Type of Land Development | Land rental |

| Property rental | |

| Property self-management | |

| Property transfer | |

| Land use rights transfer | |

| Holder of Rights to Land | State |

| Collective | |

| Both | |

| Coordinating Entity | Government |

| Collective | |

| Developer | |

| Enterprise | |

| Farmers | |

| Land or property user |

| Category | Selection | Mode I | Mode II | Mode III | Mode IV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Land Source | State-owned | ||||

| Collective-owned | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | |

| Both | |||||

| Main Agent | Government | ■ | ■ | ||

| Collective | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | |

| Developer | ■ | ||||

| Others | ■ | ||||

| Method of Land Acquisition | Rent | ■ | ■ | ||

| Expropriation | |||||

| Transaction | ■ | ||||

| Expropriation retention | ■ | ||||

| Infrastructure | Government | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ |

| Collective | ■ | ■ | ■ | ||

| Developer | ■ | ||||

| Enterprise | |||||

| Other | ■ | ||||

| Type of Land Development | Land rental | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ |

| Property rental | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | |

| Property self-management | ■ | ■ | ■ | ||

| Property transfer | ■ | ■ | ■ | ||

| Land use rights transfer | ■ | ■ | |||

| Holder of Rights To Land | State | ||||

| Collective | ■ | ■ | ■ | ||

| Both | ■ | ||||

| Coordinating Entity | Government | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ |

| Collective | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | |

| Developer | ■ | ■ | |||

| Enterprise | ■ | ||||

| Farmers | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | |

| Land or property user | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, J.; Qiu, R.; Li, K.; Xu, W. Informal Land Development on the Urban Fringe. Sustainability 2018, 10, 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10010128

Li J, Qiu R, Li K, Xu W. Informal Land Development on the Urban Fringe. Sustainability. 2018; 10(1):128. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10010128

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Jihong, Rongxu Qiu, Kaiming Li, and Wei Xu. 2018. "Informal Land Development on the Urban Fringe" Sustainability 10, no. 1: 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10010128

APA StyleLi, J., Qiu, R., Li, K., & Xu, W. (2018). Informal Land Development on the Urban Fringe. Sustainability, 10(1), 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10010128