1. Introduction

Over the past decade, there has been growing recognition that cities play a critical role in addressing climate change and advancing sustainability goals. With increasing population and economic activity concentrating in cities globally, and the rapid growth of urban areas in many parts of the world, there is a renewed interest in fostering policies, technologies, and behavioral changes that promote urban sustainability and allow for the simultaneous provision of economic growth, environmental protection, and social equity. Such transformations imply a “fundamental change in the structures, cultures, and practices” of a city, in ways that “profoundly alter the way it functions” [

1].

At the heart of urban sustainability are the policies and practices that shape municipal services such as energy and water provision, roads and sewers, and waste removal and disposal. These services are central to achieving the public good of sustainability, but in many cities private sector actors play an important role in their maintenance and operation. Following the new public management reforms of the 1990s [

2], and often encouraged by higher levels of government and international funding organizations, city governments in the U.S. have increasingly turned to the private sector for service delivery in an effort to increase economic efficiencies and reduce transaction costs [

3,

4]. In some cases, the private sector may be better poised to borrow and leverage assets compared to local governments facing debt limitations, and also have the potential to be more flexible and productive [

5,

6]. While assessments of whether greater efficiency has been achieved as a result of privatization are mixed at best, e.g., [

7], many city governments engage with the private sector for service delivery in some way. Urban sustainability initiatives engage the authority, priorities, and politics of private sector actors participating in municipal service delivery, but the role of private sector power and agency in urban sustainability transformations is often underestimated or under-theorized [

8,

9]. If sustainability is to become a central aim for city governments, this shift will take place within the existing landscape of public–private engagement in municipal service delivery.

In this article, we seek to better understand the ways in which private sector involvement can shift the political and administrative landscapes of municipal service delivery. We take as a starting point the often-overlooked fact that private engagement in local service delivery can take a variety of forms, from informal collaboration to full privatization [

5,

10]. We use the case of waste management in the Twin Cities, Minnesota to examine and discuss the issues and tensions that can arise as governments try to steer city services toward more sustainable outcomes in the varying context of privately delivered municipal services. We find that private involvement in municipal service delivery can alter the presence and form of accountability mechanisms, norms and conditions for entrepreneurship, and the feasibility and appropriateness of traditional policy tools for achieving urban sustainability transformations.

This article begins by detailing our methods and providing an overview of the waste and recycling landscape in the Twin Cities, Minnesota. Drawing also on previous examinations of privatization and municipal service delivery, we find there are three important ways private sector involvement can shape urban sustainability initiatives. We conclude with a discussion of these findings and forward recommendations for policy and future research.

2. Case Study and Methods: Organic Waste Recycling in the Twin Cities, Minnesota

The Twin Cities metro area provides an instructive case through which to assess the impact of private sector service delivery on urban sustainability initiatives. With a population of 3.5 million, this metro area is home to 64% of Minnesota’s residents and encompasses the state’s two largest cities, Minneapolis and St. Paul, in addition to over 150 smaller municipalities [

11]. In 2014, the Minnesota state legislature adopted a 75% waste diversion goal for the Twin Cities metro area by 2030. The state and county governments have determined that organic waste recycling is necessary to achieve this goal and transform the metropolitan area’s waste management system into a more sustainable model. However, despite the state-wide mandate to reduce waste to landfills and increase organics recycling, local responses have varied.

Our analysis seeks to determine the ways in which variation in governing arrangements for waste management—and specifically the role played by the private sector—may be shaping local adoption of the sustainable waste management practice of organic waste recycling. In Minnesota, purely public waste collection is rare. Instead, municipalities have privatized waste collection either through “open” collection systems, in which households select from multiple haulers in a competitive open market, or “organized” collection systems, in which firms bid on municipal contracts to be the exclusive hauler of a given service area. While “open” collection systems are completely privatized, “organized” collection systems reflect a hybrid approach, in which municipalities contract out service delivery to private operators.

The Twin Cities are not unique in their varying approaches to waste management. Open collection systems are common in the U.S., particularly in small and mid-sized cities. According to a 2008 Skumatz Economic Research Associates survey of 700 North American municipalities, 29% of municipalities reported having public waste collection, 43% reported organized systems where services are contracted out to the private sector, and 23% reported fully privatized “open” waste and recycling collection systems [

12]. Even in the European Union, waste collection is “organized” under different public–private partnership (PPP) arrangements [

5]. The Twin Cities case study therefore illustrates a range of possible ways that the private sector can be involved in delivering municipal services and the implications that this range of involvement has on urban sustainability initiatives.

In May and June of 2015, we conducted 20 semi-structured interviews in the Twin Cities metro area in order to better understand the impact of different forms of private sector involvement on waste management and the advancement of local sustainability objectives. Interviewees included state, county, and local government officials, industry representatives, scientists, and citizen advocacy groups. We asked interviewees about their experiences providing waste and recycling services in the Twin Cities metro area and the challenges they encounter in introducing organics recycling and advancing the region’s sustainability targets. These interviews were subsequently transcribed and analyzed using qualitative data analysis software. We also reviewed applicable legislation and policy documents as part of our data collection.

3. Results

Our analysis of the Twin Cities’ experience with introducing organic waste recycling reveals three important ways private sector involvement matters for urban sustainability initiatives. We present and discuss each of these in relation to both our empirical work in the Twin Cities and the broader literature on privatization and municipal service delivery.

3.1. Finding #1: Variation in Accountability Mechanisms in Urban Sustainability Initiatives

The potential of privatization to shift or erode public accountability mechanisms has been one of the most persistent critiques of municipal service privatization, e.g., [

13,

14]. While once local governments may have provided a given service through taxpayer funds and were able to direct services in response to residents’ preferences, when such services are privatized, local governments’ power and authority to affect service delivery are stifled. In the Twin Cities, and indeed in many U.S. cities, private municipal waste haulers are under no legal obligation to meet publicly determined waste diversion goals.

At the same time, privatization may alter the level of government held accountable for a given municipal service. Private energy utilities are often regulated by higher levels of government, such as the California Energy Commission and the New York Public Service Commission in the United States. When higher levels of government regulate local service delivery and neoliberal reforms, they may inadvertently diminish traditional accountability mechanisms based on the relationship between local residents and their elected officials. For example, Kadirbeyoglu and Sümer found that while privatization was originally conceived of as a mechanism for decentralization, municipalities that have privatized services such as transportation, water, and sewage find that their development pathways “are still being determined and constrained to a large extent by the rules and regulations set out by the central government” [

15]. Still, it is important to note that these regulations imposed by higher levels of government—while at once “constraining” cities—can also be in place to ensure cities’ continued independence from private interests and ensure local governments’ authority over a given policy issue. Nevertheless, many cities choose to privatize services with the explicit intent to remove government from service delivery and de-politicize municipal services [

16]. This shift in authority changes the means by which public accountability can be pursued and may introduce new interests and transaction costs to the pursuit of urban sustainability transformations.

In our analysis, we find that accountability and transparency vary with the relationship between municipalities and the private sector. In the Twin Cities, open and organized waste collection systems present different challenges for accountability. In organized collection systems, such as Minneapolis, municipalities are able to set organics recycling as a service condition through the contract and bid selection process. The process allows for greater government oversight, and facilitates greater transparency by allowing residents to express their preferences and satisfaction levels directly to city government. However, traditional accountability mechanisms are obscured in municipalities with open collection systems. The representation and responsiveness functions of government are channelled through the private waste haulers who control information and are reluctant to share resources with competitors. Private waste haulers in open systems are responsive to the needs and preferences of their paying customers, whose desires may or may not reflect government objectives and the public good. For example, industry representatives repeatedly stressed the importance of a dedicated and consistent organics waste stream in order to make organics recycling economically viable, and expressed their reluctance to provide new services for only a small group of dedicated participants. Accountability is greater when private and public actors coordinate and partner than when authority is delegated and services are purely privately delivered.

3.2. Finding #2: Introducing Private Entrepreneurship and “Political Consumption” to Urban Sustainability Initiatives

The privatization of municipal services can also produce new drivers of, and obstacles to, urban sustainability. Entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship in particular have gained attention as important drivers of major system shifts in cities [

17,

18]. Policy entrepreneurs—political actors who promote policy ideas [

19]—can help new innovations to take hold, and can promote sustainability aims in the policy process [

20,

21]. Entrepreneurs can provide leadership and innovation, and exploit opportunities for change that others don’t see or aren’t willing to pursue.

In the context of municipal services, the growing role of the private sector means that entrepreneurs may come from either the public or private sector but will bring with them unique sets of motivations, goals, and opportunities. For example, Klein et al. [

22] argue that public and private entrepreneurship shares an interest in identifying new opportunities, making decisions under uncertainty, and innovating, but differs in terms of the relative clarity of their objectives, budget constraints, and opportunities for rent seeking. In some cases the private sector may lack any incentive to innovate or participate in sustainability initiatives [

23]. However, scholars have pointed to a rise in corporate “norm-entrepreneurship”, in which corporate sector entrepreneurs advocate for the explicit institutionalization of new—often socially or environmentally responsible—norms as a means for homogenizing their regulatory environments [

24].

Public and private entrepreneurs each have unique relationships to urban residents. While policy and bureaucratic entrepreneurs may succeed in changing municipal policies and agency practices, these are subject to public scrutiny (and at least nominally) motivated by the broader public’s interest in some way. Private sector entrepreneurs, on the other hand, relate to urban residents as consumers, and their choices and opportunities are driven by actual or perceived consumption demands. For example, public sector entrepreneurs may be driven to solve a sustainability related challenge such as water pollution or rising consumer waste production because it is in the public interest, while private sector entrepreneurs may be driven to solve the same problems because of a perceived market opportunity. When urban residents act as “citizen consumers” [

25] and entrepreneurs in their own right [

26], we must understand and account for the shift in political dynamics that accompanies this [

27,

28].

The experience of the Twin Cities reveals that sustainability initiatives in fully privatized, “open” systems must be rooted in individual residents’ capacity as ‘political consumers’ rather than in any form of public sector entrepreneurship. When service delivery is fully privatized, residents must express their policy preferences through their consumption behaviour rather than electoral means.

A select number of small- and medium-sized local businesses in the Twin Cities operate in open systems and offer organics recycling services. These companies have predicated their business models on increased consumer demand and government incentives. When asked if organic waste recycling can ever be profitable, one small business representative replied:

“I’m hoping so; otherwise I wouldn’t be doing it. Hopefully I won’t go broke in that process of building it up. But I think it’s definitely going to require some support and collaboration”.

(Interview 5 May 2015)

By comparison, in organized collection systems where municipalities award waste and recycling contracts to private service providers, public officials have greater capacity to act as policy entrepreneurs, with more direct influence over which services are provided. For example, the City of Minneapolis’ organized waste and recycling system provided Mayor Betsy Hodges the authority to advance her zero waste campaign promises and implement city-wide curbside organics collection as part of her electoral mandate. Private sector involvement in municipal service delivery shapes the extent and mechanisms by which residents’ preferences are translated into sustainable outcomes.

3.3. Finding #3: Availability of Policy Tools for Urban Sustainability

Privatization can alter the feasibility and appropriateness of many traditional policy tools for promoting urban sustainability. For example, traditional tax incentives for private actors can take on a variety of forms and can be effective in promoting the adoption of certain technologies [

29]. At the same time, however, voter aversion to the cost impositions associated with government intervention (such as carbon taxes) may mean that partial, if less comprehensive and efficient, measures may be more politically feasible [

30]. Furthermore, it is not clear that policies aimed at adjusting tax and pricing models can adequately capture the full economic benefits associated with many local sustainability polices [

31]; more collaborative and multi-faceted approaches may be needed. City governments can collaborate with the private sector to share the knowledge and resources needed to coordinate infrastructure investments through Public–Private Partnerships (P3s), for example, or household communications through joint advisory boards. When services are provided by the private sector through local government contracts, public officials can help advance policy aims by ensuring that these contracts are effectively managed and risk is properly allocated [

5,

32].

Where privatization is common, strategies aimed at promoting civic leadership and private entrepreneurship may be more promising than policies rooted in traditional government accountability and feedback mechanisms. Creating incentives for “corporate norm-entrepreneurs” [

24] and channels for them to reach citizen consumers may help municipalities advance sustainability targets. It may be useful for public organizations to target the broader cultural and normative narratives that frame certain services, for example through public awareness or information campaigns. For such campaigns to be effective, it will be necessary to think about how public–private dynamics go beyond immediate service delivery, and encompass the broader systems and social practices that underpin the service [

33].

In the Twin Cities metro area, we find that the policy tools employed by state, county, and municipal governments to advance organics recycling must be tailored according to the service arrangement in particular places. In organized systems, strong government leadership can have a large impact. Governments can wield significant influence over the contract process by being directly involved in the creation, selection and enforcement of service delivery contracts. In fully privatized “open” systems, on the other hand, effective policy tools may be more indirect in nature, and target individuals in their role as service consumers through advertising and education campaigns. Private industry representatives also indicated that governments could better incentivize organics recycling in open systems by building and maintaining waste infrastructure, such as transfer stations or compost facilities, that would make private collection economically viable. Greater involvement of private actors in the delivery of municipal services highlights the need to move away from direct intervention (i.e., hierarchical, managerial, and “command and control” government programs) and instead root policy prescriptions in governance models that promote negotiation, networking, and public–private collaboration [

32,

34].

4. Discussion and Conclusion: Fostering Coordination and Collaboration for Urban Sustainability

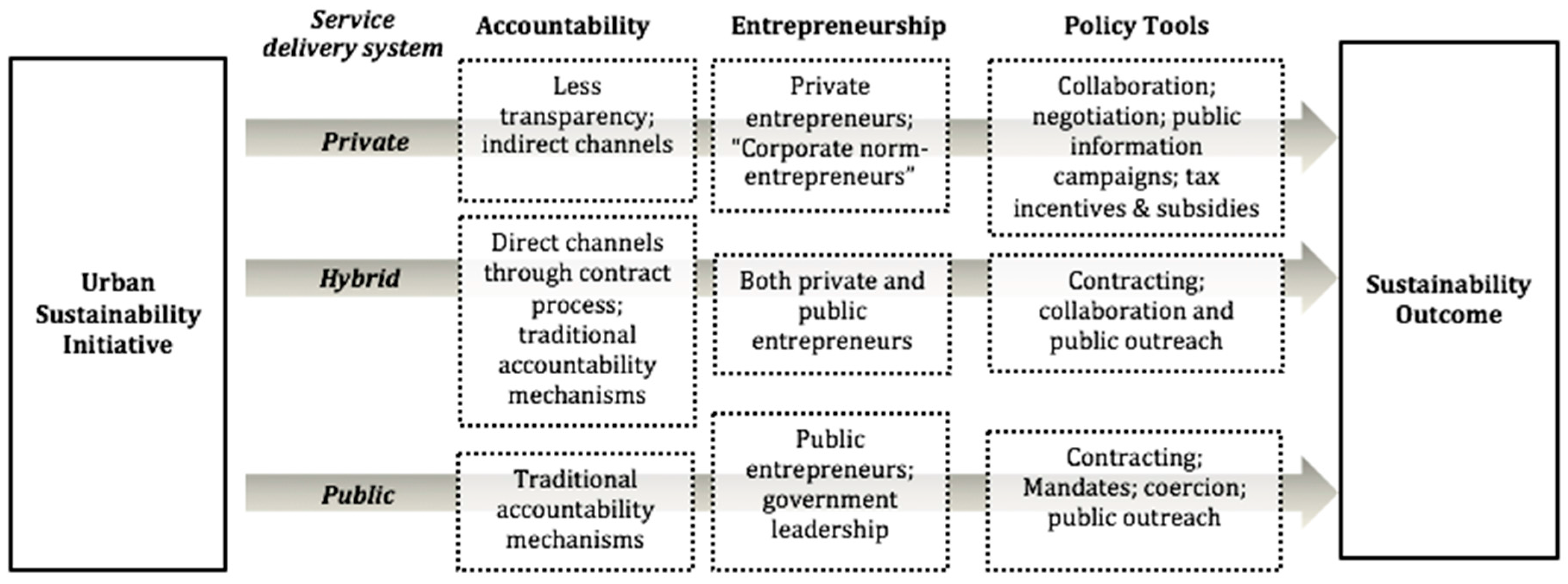

As city governments increasingly pursue sustainability initiatives and play a central role in larger sustainability transformations, understanding the specific local political and administrative dynamics of such work is critical. Our findings, based on the experience of organics recycling in the Twin Cities, point to the need for greater attention to the role of private sector involvement with municipal services in U.S. cities, and the implications for the process and outcomes of urban sustainability initiatives. Specifically, we identify three ways that private sector involvement shapes the political and administrative landscape of urban sustainability initiatives: by influencing accountability pathways, the role of public and private entrepreneurs, and the feasibility and availability of policy tools (

Figure 1). These findings make two contributions to our understanding of privatization and urban sustainability.

First, our findings underscore the importance of specifying and understanding the relationship between city governments and the private sector for the outcomes of urban sustainability initiatives. There can be significant variation in this relationship that extends beyond public versus private service delivery, with implications for the politics and administration of urban sustainability. For example, in the Twin Cities, both open and organized waste management systems involve private sector service delivery but have very different policy implications. Second, we provide useful insights for future research in this area by identifying three important mechanisms by which varied public–private relationships shape urban sustainability initiatives: accountability, entrepreneurship, and policy tools. These mechanisms serve both to specify causal pathways and generate hypotheses that can be tested in other cities and service areas.

Figure 1 demonstrates how accountability, entrepreneurship, and policy tools in urban sustainability initiatives vary depending on the private sector’s involvement in service delivery.

Our analysis also provides some initial insights for policy making, particularly that urban sustainability initiatives must account for the private sector’s involvement in providing municipal services and the likelihood that it will vary between cities. Relying on legislated goals and targets may be ineffective in a context where private service providers are not required to meet them. Conversely, there are models of privatization (such as organized waste management systems) that provide opportunities for public accountability and entrepreneurship, alongside many of the advantages to be had from privatization. Regardless of the form of service delivery, citizens must be properly engaged and at the center of the service delivery process to maintain transparency and accountability [

35,

36,

37]. However, the means by which municipal services are likely to translate into greater sustainability will again vary with the role of the private sector. If accountability and transparency are to be maintained in urban sustainability transitions, these metrics must be brought to bear on service delivery mechanisms and be given particular attention when services are privatized.

More research is needed to identify the best practices available to governments at various levels to develop municipal service arrangements that are conducive to more sustainable cities. As we noted earlier, there is a trend toward mixed-models and corporatization that show promise in their hybrid approach, but these hybrid approaches haven’t been examined from a sustainability perspective, or in light of the wide range of service needs and institutional arrangements that cities face as they move toward more sustainable forms. Future research should investigate the range of options cities are using, and identify which seem most promising for urban sustainability transformations.

Regardless of the exact form that public–private relationships take in municipal service delivery, public sector capacity is crucial [

38]. Even when services are entirely privatized, public sector capacity is necessary to develop and enforce contracts that serve public aims. However, such capacity varies widely between cities, particularly between developed and developing countries [

39]. More research is needed specifically for understanding the importance of public sector capacity in this context and strategies for increasing it when needed.

Finally, given that the private sector is likely to continue to play an important role in municipal service delivery going forward, a greater understanding of their motivations in this context is needed. When done right, there is significant potential for progressiveness through private sector engagement in sustainability transformations [

40,

41,

42,

43]. Tapping into the potential for corporate social responsibility in the realm of municipal service delivery may be a key tool for increasing the sustainability of the world’s cities.