Education Beats at the Heart of the Sustainability in Thailand: The Role of Institutional Awareness, Image, Experience, and Student Volunteer Behavior

Abstract

1. Introduction

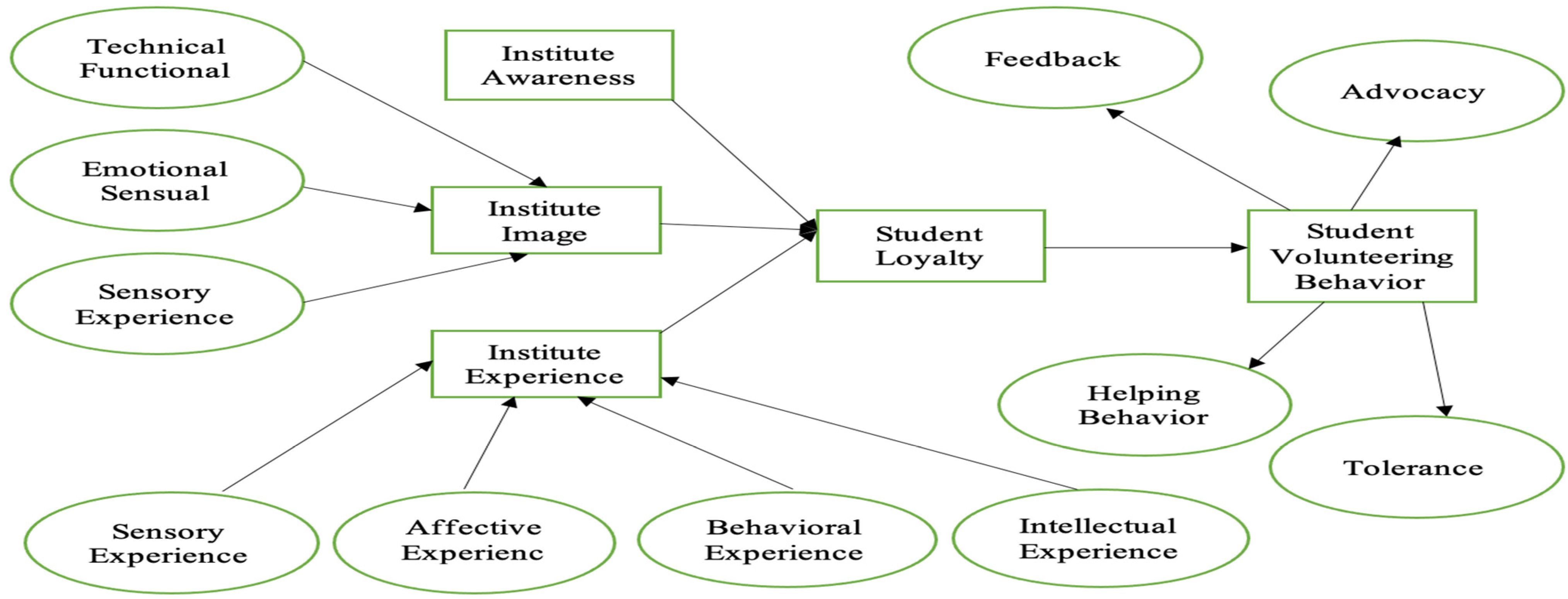

2. Literature Review

2.1. Student Volunteer Behavior (SVB)

2.2. Determinants of Student Volunteer Behavior

2.2.1. Institute Experience

2.2.2. Institute Image

2.2.3. Institute Awareness

2.2.4. Student Loyalty

3. Materials and Methods

Pilot Testing

4. Results

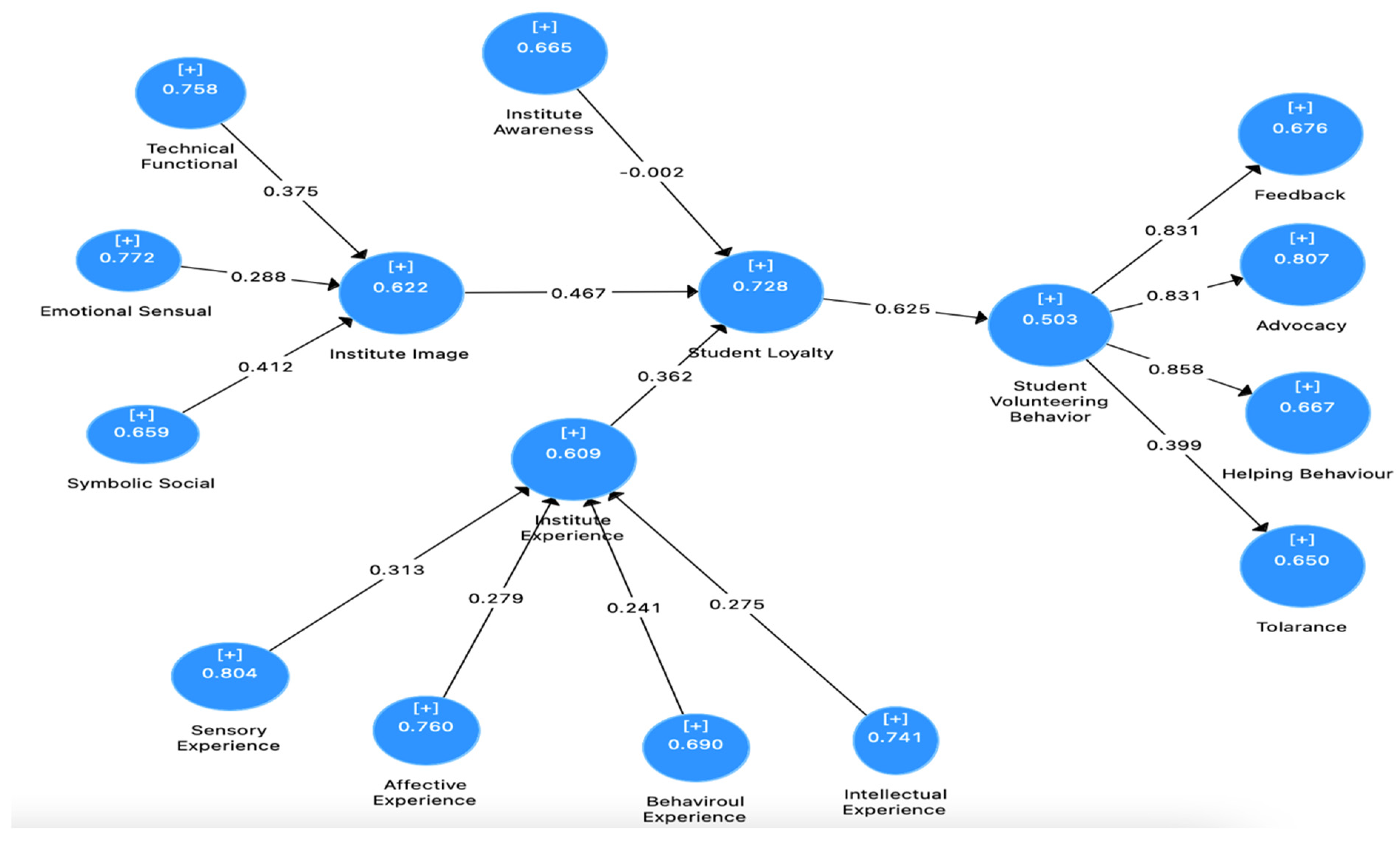

4.1. Measurement Model Assessment

4.2. Discriminant Validity

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Limitations, Implications, and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anaza, N.; Zhao, J. Encounter-based antecedents of e-customer citizenship behaviors. J. Serv. Mark. 2013, 27, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, L.; Lotz, S.L.; Kim, M. The impact of social exchange-based antecedents on customer organizational citizenship behaviors (cocbs) in service recovery. J. Mark. Dev. Compet. 2014, 8, 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, S.; Saxena, T.; Purohit, N. The New Consumer Behaviour Paradigm amid COVID-19: Permanent or Transient? J. Health Manag. 2020, 22, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Nataraajan, R.; Gong, T. Customer participation and citizenship behavioral influences on employee performance, satisfaction, commitment, and turnover intention. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curth, S.; Uhrich, S.; Benkenstein, M. How commitment to fellow customers affects the customer-firm relationship and customer citizenship behavior. J. Serv. Mark. 2014, 28, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Choi, B. The effects of three customer-to-customer interaction quality types on customer experience quality and citizenship behavior in mass service settings. J. Serv. Mark. 2016, 30, 384–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T.; Yi, Y. A review of customer citizenship behaviors in the service context. Serv. Ind. J. 2019, 41, 169–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyffenegger, B.; Kähr, A.; Krohmer, H.; Hoyer, W.D. How Should Retailers Deal with Consumer Sabotage of a Manufacturer Brand? J. Assoc. Consum. Res. 2018, 3, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polo, Y.; Sese, F.J.; Verhoef, P.C. The effect of pricing and advertising on customer retention in a liberalizing market. J. Interact. Mark. 2011, 25, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, R.; Raza, M.; Sawangchai, A.; Somtawinpongsai, C. The challenging factors affecting women entrepreneurial activities. J. Lib. Int. Aff. 2022, 8, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.H.; Yoo, J.J. Customer-to-customer interactions on customer citizenship behavior. Serv. Bus. 2017, 11, 117–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, L.; Lotz, S.L. Exploring antecedents of customer citizenship behaviors in services. Serv. Ind. J. 2017, 38, 607–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettencourt, L.A. Customer voluntary performance: Customers as partners in service delivery. J. Retail. 1997, 73, 383–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, A.; Arndt, A.D. How personal costs influence customer citizenship behaviors. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 39, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Gong, T. Customer value co-creation behavior: Scale development and validation. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1279–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lishan, X.; Wenxuan, Z.; Yinmei, P. Mediation effect of brand relationship quality between airline brand experience and customer citizenship behavior. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Service Systems and Service Management, Beijing, China, 25–27 June 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revilla-Camacho, M.; Vega-Vázquez, M.; Cossío-Silva, F.J. Customer participation and citizenship behavior effects on turnover intention. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1607–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaakkola, E.; Alexander, M. The role of customer engagement behavior in value co-creation. J. Serv. Res. 2014, 17, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wei, M. Hotel servicescape and customer citizenship behaviors: Mediating role of customer engagement and moderating role of gender. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 587–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lyu, S.O. Relationships among green image, consumer attitudes, desire, and customer citizenship behavior in the airline industry. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2019, 14, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Chen, M. Research on Influence of the Congruence of Self-Image and Brand Image on Consumers’ Citizenship Behavior. Open J. Bus. Manag. 2018, 6, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nagy, E.-S.A.; Marzouk, W.G. Factors affecting customer citizenship behavior: A model of university students. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2018, 10, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.S.Y.; Gaur, S.S.; Chew, K.W.; Khan, N. Gender roles and customer organisational citizenship behaviour in emerging markets. Psychol. Mark. 2017, 30, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Poon, P.; Zhang, W. Brand experience and customer citizenship behavior: The role of brand relationship quality. J. Consum. Mark. 2017, 34, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, V.W.S.; Chen, P.-J.; Schuckert, M. Managing customer citizenship behaviour: The moderating roles of employee responsiveness and organizational reassurance. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-Y.D.; Wu, S.-H.; Huang, S.C.-T. From mandatory to voluntary: Consumer cooperation and citizenship behaviour. Serv. Ind. J. 2017, 37, 521–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tonder, E.; Fullerton, S.; De Beer, L.T.; Saunders, S.G. Social and personal factors influencing green customer citizenship behaviours: The role of subjective norm, internal values and attitudes. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 71, 103–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Education Dropout Figures Keep Rising. Bangkok Post. 25 June 2021. Available online: https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/general/2138011/education-dropout-figures-keep-rising (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Saokaew, D. COVID-19: Thailand’s School Dropout Rate Soars. CGTN. 8 July 2021. Available online: https://news.cgtn.com/news/2021-07-08/COVID-19-Thailand-s-school-dropout-rate-soars-11JmsBKXkv6/index.html (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- Malaysia to Recalibrate Its Strategy as 200k Int’l Student Target by 2020 Looks Unlikely. The Pie News, 27 September 2020.

- Balaji, M.S. Managing customer citizenship behavior: A relationship perspective. J. Strateg. Mark. 2014, 22, 222–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, C. The Functions of the Executive; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Groth, M. Customers as good soldiers: Examining citizenship behaviors in internet service deliveries. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.-C.; Luo, S.-J.; Yen, C.-H.; Yang, Y.-F. Brand attachment and customer citizenship behaviors. Serv. Ind. J. 2016, 36, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Gong, T. The antecedents and consequences of service customer citizenship and badness behavior. Seoul J. Bus. 2006, 12, 145–176. Available online: http://strathprints.strath.ac.uk/38577/ (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Hansong, Y.; Keyi, W.; Dan, Y.; Rong, L. The influences of customer citizenship behaviors on brand reputation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Management, Innovation Management and Industrial Engineering, Sanya, China, 20–21 October 2012; pp. 393–396. [Google Scholar]

- Lacey, R.; Morgan, R.M. Customer advocacy and the impact of B2B loyalty programs. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2008, 24, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.-C.; Wu, C.-S.; Yen, C.-H.; Chen, C.-Y. Tour leader attachment and customer citizenship behaviors in group package tour: The role of customer commitment. Asia Pacific J. Tour. Res. 2015, 21, 642–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; Groth, M.; Walsh, G.; Hennig-Thurau, T. Consumer perceptions of online shopping environments. Psychol. Mark. 2014, 30, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoghbi-Manrique-De-Lara, P.; Suárez-Acosta, A.M.; Guerra-Báez, R.M. Customer citizenship as a reaction to hotel’s fair treatment of staff: Service satisfaction as a mediator. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2017, 17, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamim, A.; Ghazali, Z.; Jamak, A.B.S.A. Extrinsic experiential value as an antecedent of customer citizenship behavior. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Technology Management and Emerging Technologies (ISTMET), Langkawi Island, Malaysia, 25–27 August 2015; pp. 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, V.; Quoquab, F.; Ahmad, F.S.; Mohammad, J. Mediating effects of students’ social bonds between self-esteem and customer citizenship behaviour in the context of international university branch campuses. Asia Pacific J. Mark. Logist. 2017, 29, 305–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Hirschman, E.C. The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feeling, and fun. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, B. Experiential marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 1999, 15, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brakus, J.J.; Schmitt, B.H.; Zarantonello, L. Brand experience: What is it? How is it measured? Does it affect loyalty? J. Mark. 2009, 73, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarantonello, L.; Schmitt, B.H. Using the brand experience scale to profile consumers and predict consumer behaviour. J. Brand Manag. 2010, 17, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleff, T.; Walter, N.; Xie, J. The effect of online brand experience on brand loyalty: A web of emotions. IUP J. Brand Manag. 2018, 15, 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Shamim, A.; Ghazali, Z. An integrated model of corporate brand experience and customer value co-creation behaviour. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2016, 44, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarantonello, L.; Schmitt, B.H. The impact of event marketing on brand equity: The mediating roles of brand experience and brand attitude. Int. J. Advert. 2013, 32, 255–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, J.U.; Rahman, Z. Examining the effects of brand love and brand image on customer engagement: An empirical study of fashion apparel brands. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2016, 7, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirsehan, T.; Kurtuluş, S. Measuring brand image using a cognitive approach: Representing brands as a network in the Turkish airline industry. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2018, 67, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyadzayo, M.W.; Khajehzadeh, S. The antecedents of customer loyalty: A moderated mediation model of customer relationship management quality and brand image. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 30, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, M.; Pan, S.; Setiono, R. Dimensions and Purchase Behavior: A multicountry analysis. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2004, 32, 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-Based Brand Equity. Source J. Mark. 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdiawan, Y.; Hermawan, A.; Wardana, L.W.; Arief, M. Satisfaction as effect mediation of brand image and customer relationship management on customer’s loyalty. In Proceedings of the The First International Research Conference on Economics and Business, Medan, Indonezia, 8–9 October 2018; pp. 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sondoh, L.; Omar, M.; Wahid, N.; Ismail, I.; Harun, A. The effect of brand image on overall satisfaction and loyalty intention in the context of color cosmetic. Asian Acad. Manag. 2007, 12, 83–107. Available online: http://web.usm.my/aamj/12.1.2007/AAMJ 12-1-6.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2022).

- Lucas, D.B.; Britt, S.H. Advertising Psychology and Research; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Langaro, D.; Rita, P.; Salgueiro, M. Do social networking sites contribute for building brands? Evaluating the impact of users’ participation on brand awareness and brand attitude. J. Mark. Commun. 2018, 24, 146–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A. Managing Brand Equity; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, M.; Martín-Consuegra, D.; Díaz, E.; Molina, A. Determinants and outcomes of price premium and loyalty: A food case study. J. Consum. Behav. 2018, 17, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rompas, I.A.; Pangemanan, S.S.; Rumokoy, F.S. The impact of price and brand awareness toward brand loyalty of tri provider in north sulawesi case study: University students UNKLAB, DE LA SALLE, UNIMA, AND, UNSRAT. J. EMBA 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bove, L.L.; Pervan, S.J.; Beatty, S.E.; Shiu, E. Service worker role in encouraging customer organizational citizenship behaviors. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 698–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, G.S. A Two-Dimensional concept of brand loyalty. J. Advert. Res. 1969, 9, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, A.S.; Basu, K. Customer loyalty: Toward an integrated conceptual framework. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1994, 22, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, J.; Kyner, D.B. Brand loyalty vs. repeat purchasing behavior. J. Mark. Res. 1973, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, M.T. Relation of consumers’ buying habits to marketing methods. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1923, 1, 282–289. [Google Scholar]

- Bartikowski, B.; Walsh, G. Investigating mediators between corporate reputation and customer citizenship behaviors. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karjaluoto, H.; Jayawardhena, C.; Leppäniemi, M.; Pihlström, M. How value and trust influence loyalty in wireless telecommunications industry. Telecomm. Policy 2012, 36, 636–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiee, M.M.; Sanayei, A.; Shahin, A.; Dolatabadi, H.R. The role of brand image in forming airlines passengers’ purchase intention: Study of Iran aviation industry. Int. J. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2014, 19, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buil, I.; Martínez, E.; de Chernatony, L. The influence of brand equity on consumer responses. J. Consum. Mark. 2013, 30, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Chen, J.; Shirkey, G.; John, R.; Wu, S.R.; Park, H.; Shao, C. Applications of structural equation modeling (SEM) in ecological studies: An updated review. Ecol. Process. 2016, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, G.A.; Brooks, G.P. Initial scale development: Sample Size for pilot studies. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2010, 70, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, H.H. Modern Factor Analysis; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner, H.; Weijters, B.; Pieters, R. The biasing effect of common method variance: Some clarifications. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2021, 49, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.R.; Schindler, P.S. Business Research Methods; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1998; Volume 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekaran, U.; Bougie, R. Research Methods for Business; A Skill Building Approach; John and Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ursachi, G.; Horodnic, I.A.; Zait, A. How reliable are measurement scales ? External factors with indirect influence on reliability estimators. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 20, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Plan. 2013, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Thiele, K.O. Mirror, mirror on the wall: A comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In Modern Methods for Business Research; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Am. Mark. Assoc. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The Use of Partial Least Squares Path Modeling In International Marketing; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Smith, D.; Reams, R.; Hair, J.F., Jr. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): A useful tool for family business researchers. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2014, 5, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hult, G.T.M.; Hair, J.F., Jr.; Proksch, D.; Sarstedt, M.; Pinkwart, A.; Ringle, C.M. Addressing endogeneity in international marketing applications of partial least squares structural equation modeling. J. Int. Mark. 2018, 26, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Using partial least squares path modeling in advertising research: Basic concepts and recent issues. In Handbook of Research on International Advertising; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N.B. A Primer for Soft Modeling; University of Akron Press: Akron, OH, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Hollingsworth, C.L.; Randolph, A.B.; Chong, A.Y.L. An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2017, 117, 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Rahman, Z.; Fatma, M. The role of customer brand engagement and brand experience in online banking. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2016, 34, 1025–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, V.; Thomas, S. Direct and indirect effect of brand experience on true brand loyalty: Role of involvement abstract. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2018, 30, 725–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Westhuizen, L.-M. Brand loyalty: Exploring self-brand connection and brand experience. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2018, 27, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahi, S. Impact of customer value, public relations perception and brand image on customer loyalty in services sector of Pakistan. Arab. J. Bus. Manag. Rev. 2016, 3, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinomona, R.; Maziriri, E.T. The influence of brand awareness, brand association and product quality on brand loyalty and repurchase intention: A case of male consumers for cosmetic brands in South Africa. J. Bus. Retail Manag. Res. 2017, 12, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratama, H.; Suprapto, B. The Effect of Brand Image, Price, and Brand Awareness on Brand Loyalty: The Rule of Customer Satisfaction as a Mediating Variable. Glob. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2017, 5, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Chang, A. Factors affecting college students’ brand loyalty toward fast fashion. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2018, 46, 90–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, P.G.; Razzaque, M.A.; Terry, C.S.L. Customer citizenship behaviour in service organisations: A social exchange model. In Proceedings of the Australian and New Zealand Academy Conference, Fremantle, Australia, 2–5 December 2003; pp. 2079–2089. [Google Scholar]

- Shahzad, A.; Hassan, R.; Aremu, A.Y.; Hussain, A.; Lodhi, R.N. Effects of COVID-19 in E-learning on higher education institution students: The group comparison between male and female. Qual. Quant. 2020, 55, 805–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennings, R. Malaysian COVID-19 Cases Soar to Thousands per Day. Voanews, 22 January 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Owens, T.R.; Wang, C. Community-based learning: A foundation for meaningful educational reform. Sch. Improv. Res. Ser. 1996. Available online: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/slceslgen/37 (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Kornbluh, M.; Wilking, J.; Roll, S.; Banks, L.; Stone, H.; Candela, J. Learning and Doing Together: Student Outcomes from an Interdisciplinary, Community-Based Research Course on Homelessness in a Local Community. J. Community Engagem. Scholarsh. 2020, 13, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaque, I.; Khan, M.R.; Zahra, R.; Fatima, S.M.; Ejaz, M.; Lak, T.A.; Rizwan, M.; Awais-E-Yazdan, M.; Raza, M.; Psychologist, G.S.M.T.H.C. Prevalence of Coronavirus Anxiety, Nomophobia, and Social Isolation Among National and Overseas Pakistani Students. J. Popul. Soc. Stud. 2022, 30, 408–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, A.D.; Ibáñez-Carrasco, F.; Craig, S.L.; Carusone, S.C.; Montess, M.; Wells, A.; Ginocchio, G.F. A blended learning curriculum for training peer researchers to conduct community-based participatory research. Action Learn. Res. Pract. 2018, 15, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsin, M.; Jamil, K.; Naseem, S.; Sarfraz, M.; Ivascu, L. Elongating Nexus Between Workplace Factors and Knowledge Hiding Behavior: Mediating Role of Job Anxiety. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, 15, 441–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarfraz, M.; Ivascu, L.; Belu, R.; Artene, A. Accentuating the interconnection between business sustainability and organizational performance in the context of the circular economy: The moderating role of organizational competitiveness. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2021, 30, 2108–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioca, L.I.; Ivascu, L.; Turi, A.; Artene, A.; Gaman, G.A. Sustainable Development Model for the Automotive Industry. Sustain. J. 2019, 11, 6447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Student Volunteer Behavior |

| I provide useful ideas to institute staff to improve their services. |

| I give my feedback to the institute whenever I receive its services. |

| I always seek help from institute staff if I have any problem. |

| I say constructive words about this institute to others. |

| I recommend this institute to others. |

| I am inspired by this institute and endorse it to others. |

| I assist fellow students when they seek help. |

| I help fellow students when they face any problem. |

| I teach fellow students the right use of services. |

| I give advice to fellow students about the provided services of this institute. |

| I tolerate it if services are not delivered as per my expectations. |

| If the institute makes a mistake during encounters, I prefer to be persistent. |

| I choose to wait if I have to wait longer than normal to receive the service. |

| Student Loyalty |

| I prefer this institute more than any other institute. |

| I consider this institute best serves my purpose. |

| I choose the services of my institute over those of its competitors. |

| I trust that my institute is better than other institutes. |

| The offers of my institute always superior to those of others. |

| Institute Experience |

| This institute leaves a positive impression on my senses. |

| This institute is interesting in a sensory way. |

| This institute is appealing to my senses. |

| This institute creates positive feelings. |

| I have positive feelings about this institute. |

| This institute focuses on creating positive emotions. |

| I engage in physical actions that favor this institute. |

| This institute encourages me to think about lifestyle. |

| This institute emphases experiences through activities. |

| I engage in a lot of positive thinking when I encounter this institute. |

| I always have positive thinking about this institute. |

| This institute stimulates my curiosity. |

| Institute Image |

| This institute is a good choice for study. |

| This institute acts as expected from an institute. |

| My opinion is good about the study and related issues of this institute. |

| I choose this institute due to its advantages in comparison with other institutes. |

| This institute is exciting. |

| I have profound interest in this institute. |

| The institute is luxurious. |

| This institute creates a positive image of me. |

| This institute fits my personality. |

| This institute is a good fit for my social status. |

| This institute leaves a positive impression on other students as well. |

| I have a progressive image of the institute owning the country. |

| Institute Awareness |

| I am aware of the services of this institute. |

| When I consider institutes for study, this institute is the first to come to my mind. |

| I am familiar with this institute. |

| I know what the institute looks like. |

| I can differentiate this institute from another institute. |

| First Order | Second Order | Item Labeling | Loadings | CR | AVE | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensory | 0.925 | 0.804 | 0.878 | |||

| IE1 | 0.906 | |||||

| IE2 | 0.888 | |||||

| IE3 | 0.896 | |||||

| Affective | 0.908 | 0.767 | 0.848 | |||

| IE4 | 0.858 | |||||

| IE5 | 0.897 | |||||

| IE6 | 0.859 | |||||

| Behavioral | 0.885 | 0.719 | 0.805 | |||

| IE7 | 0.821 | |||||

| IE8 | 0.823 | |||||

| IE9 | 0.849 | |||||

| Intellectual | 0.900 | 0.750 | 0.833 | |||

| IE10 | 0.861 | |||||

| IE11 | 0.860 | |||||

| IE12 | 0.861 | |||||

| Institute Experience | 0.942 | 0.802 | 0.942 | |||

| Sensory | 0.916 | |||||

| Affective | 0.907 | |||||

| Behavioral | 0.873 | |||||

| Intellectual | 0.907 | |||||

| Technical Functional | 0.924 | 0.752 | 0.890 | |||

| II1 | 0.874 | |||||

| II2 | 0.890 | |||||

| II3 | 0.879 | |||||

| II4 | 0.839 | |||||

| Emotional Sensual | 0.909 | 0.770 | 0.850 | |||

| II5 | 0.873 | |||||

| II6 | 0.867 | |||||

| II7 | 0.901 | |||||

| Symbolic Social | 0.907 | 0.663 | 0.872 | |||

| II8 | 0.862 | |||||

| II9 | 0.846 | |||||

| II10 | 0.799 | |||||

| II11 | 0.847 | |||||

| II12 | 0.706 | |||||

| Institute Image | 0.948 | 0.859 | 0.943 | |||

| Technical Functional | 0.915 | |||||

| Emotional Sensual | 0.934 | |||||

| Symbolic Social | 0.937 | |||||

| Institute Awareness | Unidimensional | 0.908 | 0.665 | 0.876 | ||

| IA1 | 0.795 | |||||

| IA2 | 0.864 | |||||

| IA3 | 0.865 | |||||

| IA4 | 0732 | |||||

| IA5 | 0.814 | |||||

| Student Loyalty | Unidimensional | 0.931 | 0.731 | 0.908 | ||

| SL1 | 0.832 | |||||

| SL2 | 0.886 | |||||

| SL3 | 0.876 | |||||

| SL4 | 0.865 | |||||

| SL5 | 0.805 | |||||

| Feedback | 0.881 | 0.712 | 0.798 | |||

| SVB1 | 0.846 | |||||

| SVB2 | 0.880 | |||||

| SVB3 | 0.803 | |||||

| Advocacy | 0.926 | 0.806 | 0.879 | |||

| SVB4 | 0.878 | |||||

| SVB5 | 0.916 | |||||

| SVB6 | 0.899 | |||||

| Helping Behavior | 0.889 | 0.668 | 0.834 | |||

| SVB7 | 0.817 | |||||

| SVB8 | 0.800 | |||||

| SVB9 | 0.829 | |||||

| SVB10 | 0.832 | |||||

| Tolerance | 0.876 | 0.702 | 0.787 | |||

| SVB11 | 0.835 | |||||

| SVB12 | 0.829 | |||||

| SVB13 | 0.848 | |||||

| Student Volunteering Behavior | 0.604 | 0.856 | 0.891 | |||

| Feedback | 0.789 | |||||

| Advocacy | 0.876 | |||||

| Helping Behavior | 0.785 | |||||

| Tolerance | 0.566 |

| Hypothesis/Paths | Beta | Sig | VIF | Effect | Q2 | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Institute Experience ----> Student Loyalty | 0.359 | 0.000 | 3.726 | 0.095 | 0.172 | 0.442 |

| Institute Image ----> Student Loyalty | 0.468 | 0.000 | 3.879 | 0.155 | ||

| Institute Awareness ----> Student Loyalty | 0.001 | 0.987 | 1.330 | 0.000 | ||

| Student Loyalty ----> Student Volunteering Behavior | 0.667 | 0.000 | 1.00 | 0.800 | ||

| Institute Experience ----> Student Loyalty ----> Student Volunteer Behavior | 0.239 | 0.000 | ||||

| Institute Image ----> Student Loyalty ----> Student Volunteer Behavior | 0.312 | 0.000 | ||||

| Institute Awareness ----> Student Loyalty ----> Student Volunteer Behavior | 0.001 | 0.987 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Raza, M.; Khalid, R.; Ivascu, L.; Kasuma, J. Education Beats at the Heart of the Sustainability in Thailand: The Role of Institutional Awareness, Image, Experience, and Student Volunteer Behavior. Sustainability 2023, 15, 918. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15020918

Raza M, Khalid R, Ivascu L, Kasuma J. Education Beats at the Heart of the Sustainability in Thailand: The Role of Institutional Awareness, Image, Experience, and Student Volunteer Behavior. Sustainability. 2023; 15(2):918. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15020918

Chicago/Turabian StyleRaza, Mohsin, Rimsha Khalid, Larisa Ivascu, and Jati Kasuma. 2023. "Education Beats at the Heart of the Sustainability in Thailand: The Role of Institutional Awareness, Image, Experience, and Student Volunteer Behavior" Sustainability 15, no. 2: 918. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15020918

APA StyleRaza, M., Khalid, R., Ivascu, L., & Kasuma, J. (2023). Education Beats at the Heart of the Sustainability in Thailand: The Role of Institutional Awareness, Image, Experience, and Student Volunteer Behavior. Sustainability, 15(2), 918. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15020918