This study examined how physiotherapists in Cyprus adhere to internationally recommended management strategies for RCRSP. Almost all respondents recommended some form of education and exercise as management, minimal use of imaging, injection, and surgery, indicating consistency with guideline-recommended care. However, some discrepancies exist, particularly in exercise prescription and adjunct therapies. Findings are comparable to those found internationally in nations such as the United Kingdom, Belgium/the Netherlands, Australia, Italy and Greece; Cypriot physiotherapists exhibited variability in the prevalence and methodology of guideline-congruent management. Such variations may be attributed to local educational frameworks, healthcare system characteristics, and patient expectations.

4.1. Imaging, Injection, Surgery

The study findings on Cypriot physiotherapists’ referral practices for imaging, injections, and surgery reveal a strong inclination towards conservative management strategies, consistent with international guidelines that advocate for non-invasive approaches in the absence of red flags [

16,

25]. Imaging is indicated if a 4–6 week trial of active treatment fails, and both injection therapy and surgical consultation should only be considered after 12 weeks of conservative management [

16,

18,

25]. Consistent with guideline recommendations, most respondents (64%, n = 91/143) would not recommend imaging for the patient in the case vignette and would not consider a surgical opinion (73%, n = 104/143). This is encouraging, as premature imaging and early surgical referral have been associated with increased healthcare costs, patient anxiety, and unnecessary interventions in musculoskeletal disorders [

54]. Over-reliance on imaging may reinforce pathoanatomical beliefs in patients, potentially undermining self-management and recovery [

55].

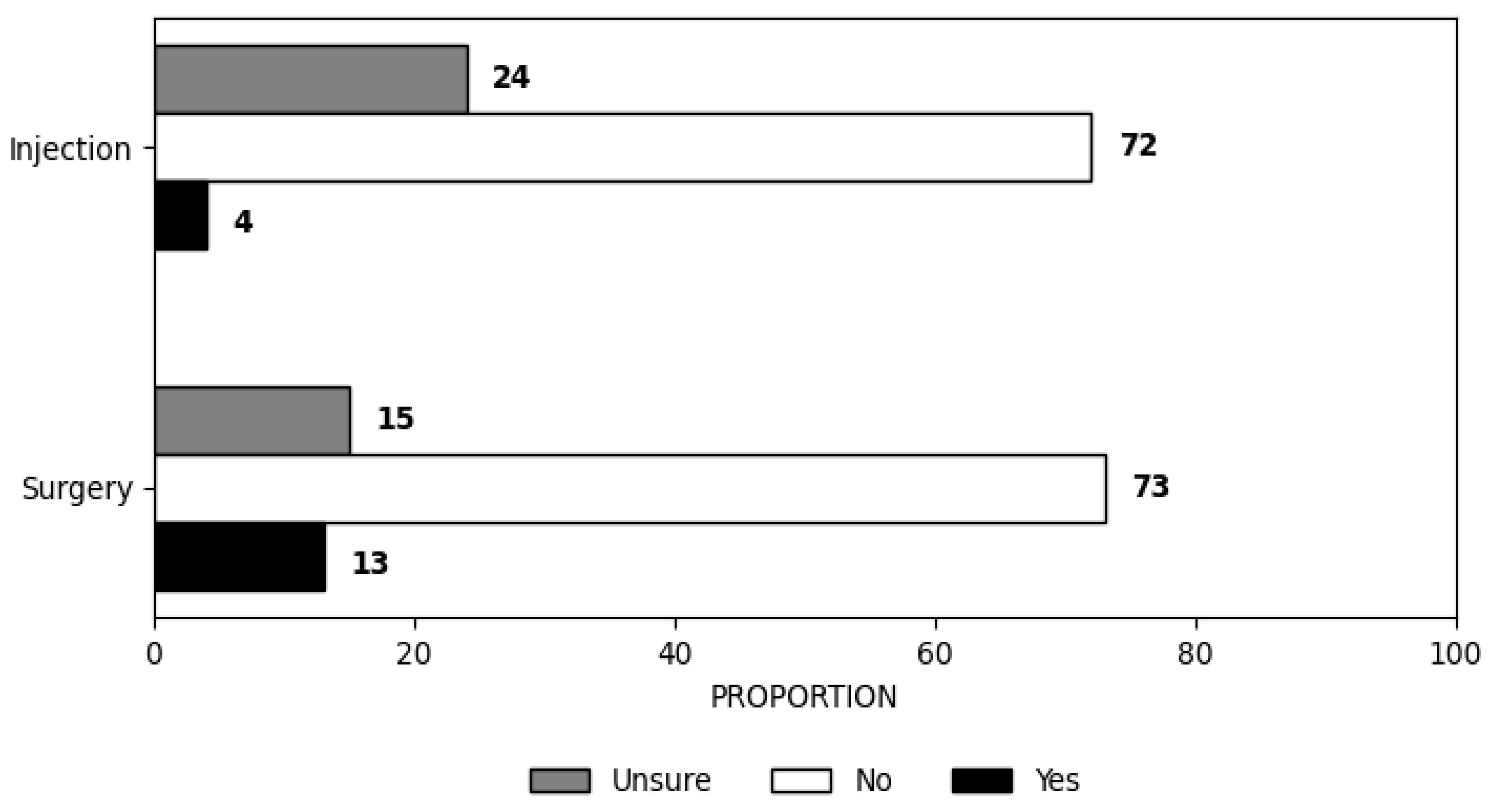

Injection was not recommended by most respondents (72%, n = 103/143) in line with guideline recommendations. The remaining respondents were uncertain (24%, n = 34/143), and only a minority would recommend injection (4%, n = 6/143). However, it is noteworthy that a subset of physiotherapists exhibited deviations from these guidelines, indicating variability in practice that may be influenced by personal interest or specialisation in shoulder-related conditions.

A statistically significant association was observed between special interest in shoulder pain or rotator cuff-related pain, surgery, and injection (

p = 0.026 and

p = 0.002, respectively). The association with surgery was weak (Cramer’s V = 0.186), while the association with injection was moderate (Cramer’s V = 0.253). This finding suggests that physiotherapists with a special interest in shoulder pain or rotator cuff-related pain were more likely to recommend surgical interventions and injections. This finding is counterintuitive, as one might expect that physiotherapists with a special interest in shoulder conditions would demonstrate stronger alignment with evidence-based guidelines. However, it is important to note that this “special interest” was self-reported and may not equate to formal training or advanced clinical expertise. Previous literature suggests that self-perceived expertise does not always translate into guideline adherence [

38,

39]. It is also possible that increased interest may lead to a more biomedical interpretation of pathology, influencing decisions towards diagnostic imaging or interventional referrals. Studies have also shown that clinicians with a strong interest in a specific area may also be more confident in deviating from guidelines based on personal experience, perceived clinical complexity, or outdated knowledge [

38,

56]. This highlights the need for continuous professional development and critical appraisal skills to ensure that clinical interests are aligned with current evidence-based practice.

Despite the noted associations, most physiotherapists (76%) preferred basic imaging techniques, reserving advanced imaging such as MRI for specific cases, particularly when considering surgery or injections. The study found that MRI use was significantly associated with recommendations for surgery (“Yes/Unsure”), with those recommending MRI being almost seven times more likely to do so (Exp(B) = 6.944,

p < 0.001), suggesting a reliance on advanced imaging to inform surgical decisions. This aligns with the established role of MRI in confirming surgical indications, such as assessing rotator cuff integrity or ruling out other complex shoulder pathologies. The reliance on MRI in these cases reflects its utility in enhancing diagnostic accuracy and guiding invasive interventions, consistent with global practices [

57,

58,

59]. Nevertheless, this tendency towards advanced imaging raises concerns about the potential for overdiagnosis and overtreatment, as highlighted by previous studies linking premature diagnostic imaging to adverse outcomes, including the nocebo effect [

60,

61,

62]. For example, patients with shoulder pain may misinterpret imaging findings, such as tendon tears, as necessitating surgical intervention, even when conservative management could suffice [

63,

64]. Therefore, physiotherapists must contextualise imaging results accurately and align them with evidence-based care principles to mitigate misconceptions.

Physiotherapists working in non-private settings were five times more likely to use MRI than those in private practice (Exp(B) = 5.049,

p = 0.014). This suggests that access to advanced imaging modalities may be more readily available in public or institutional work settings, where structured diagnostic protocols often govern patient care [

65,

66]. Additionally, economic and administrative factors, such as equipment availability, reimbursement incentives, or pressure to justify care pathways, can influence clinical decisions, potentially leading to the overuse of imaging [

58,

67]. These system-level considerations may partly explain why physiotherapists in non-private settings were significantly more likely to recommend MRI, highlighting the importance of aligning institutional protocols with up-to-date clinical guidelines. In contrast, private practice settings may prioritise cost-effectiveness and favour conservative approaches, aligning with international recommendations to reserve MRI for cases where it directly influences management decisions [

67,

68].

In terms of injection practices, the study found that 28% of physiotherapists were either uncertain about or recommended injections despite guidelines discouraging their routine use without clear indications [

16,

25]. The long-term efficacy of corticosteroid injections remains contentious, with research indicating potential risks such as persistent pain and tendon degradation and an increased likelihood of injury recurrence [

69,

70,

71]. This underscores the necessity for ongoing professional development to keep patients informed about the adverse effects and limited benefits of such interventions. Furthermore, only 27% of participants suggested surgery, reinforcing the conservative approach observed among the majority. However, the association between MRI use and surgical recommendations suggests a reliance on advanced diagnostics that may inadvertently influence decision-making towards more invasive options.

Compared to other countries, Cypriot physiotherapists were consistent in their recommendations for injection management, considering guideline recommendations (72%), similar to France and Australia, with over 70% [

36,

37]. The referral rate for imaging by Cypriot physiotherapists (36%, n = 52/143) is higher than those in Australia (6.4%), the United Kingdom (9.0%), France (12.6%), and Belgium/the Netherlands (31.0%), but lower than in Italy (42.0%) and Greece (44%) [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. No indication for surgery was stated in 73% (n = 104/143) of Cypriot physiotherapists compared to Greece (74%), Australia (90.0%), France (89.3%), Italy (62.0%), Belgium/the Netherlands (70.0%) [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. This pattern may be due to different practice standards; in practices in countries like France, Australia, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom, physiotherapists have expanded their scope of practice as first-contact practitioners, necessitating decision-making regarding referral for interventionalist care [

72,

73,

74,

75,

76] compared to Belgium, Italy, Greece, and Cyprus [

56].

4.2. Education

Education is recommended as an essential component of RCRSP management; however, guidelines provide limited detail on specific educational topics and delivery methods beyond advice related to activity modification and risk factors [

16,

18,

25]. This is evident in the education approaches adopted by practitioners. Consistent with guideline recommendations, all Cypriot physiotherapists reported providing some form of education, although there was variability in the specific topics covered. Cypriot physiotherapists were more likely to recommend education on activity modification (81%, n = 116/143) compared to physiotherapists in France (69.9%), but this was similar to rates in Australia (85.3%), Greece (83%), and Belgium/the Netherlands (80.0%) [

35,

36,

37,

39]. They were also less likely to recommend education concerning the timing and indication for imaging (38%, n = 55/143), injection (13%, n = 18/143) and surgery (16%, n = 23/143) compared to Australian physiotherapists (50.4% 35.7% and 25.1%, respectively) [

36], but more likely than French (14.6%, 7.8% and 6.3%, respectively) [

37] and Greek physiotherapists (28%, 9% and 12%, respectively [

39]. This may be because, in Australia, physiotherapists are first-contact practitioners [

72], meaning patients can access their services without a referral from another medical professional. In contrast, in Cyprus, Greece, and France, such referrals are typically required [

73]. However, there was considerable variation in the educational strategies used, highlighting a lack of consistency. This emphasises the need for more precise guidelines to reduce this variability and promote uniformity in educational approaches.

4.3. Exercise Prescription

The physiotherapeutic management of RCRSP is characterised by a high prevalence of exercise prescription among Cypriot practitioners, with 99% (n = 142/143) of surveyed physiotherapists incorporating exercise as an integral component of their treatment protocols. This practice is in line with guideline recommendations, as evidenced by responses to the clinical vignette [

16,

18,

25,

46]. However, this widespread adoption is accompanied by significant variability in the specific practices used to deliver exercise, such as dosage, progression, type of exercise, etc. This variability can be attributed to the extensive range of exercise trials and the inherent heterogeneity of interventions documented in the literature [

21,

77] and the lack of evidence demonstrating the superiority of any specific type of exercise over another [

21].

The survey demonstrated that a significant proportion of physiotherapists prioritised exercise interventions targeting the rotator cuff musculature (76%, n = 109/143), isometric shoulder exercise (67%, n = 96/143), global exercises addressing the entire upper limb kinetic chain (63%, n = 90/143) and scapula-specific exercises (57%, n = 82/143). These exercises are consistent with evidence-based recommendations in the current literature [

24,

26,

31,

78,

79] and reflect similar findings in France, Australia, Belgium/The Netherlands, Italy and Greece [

33,

34,

35,

36]. Regarding contraction type, more respondents recommended isometric exercise (67%, n = 96/143) than eccentric (53%, n = 76/143) or isotonic (34%, n = 49/143). This was similar to findings in Australia, France, Italy, and Greece that recommended isometric exercise despite the limited evidence supporting its effectiveness [

21].

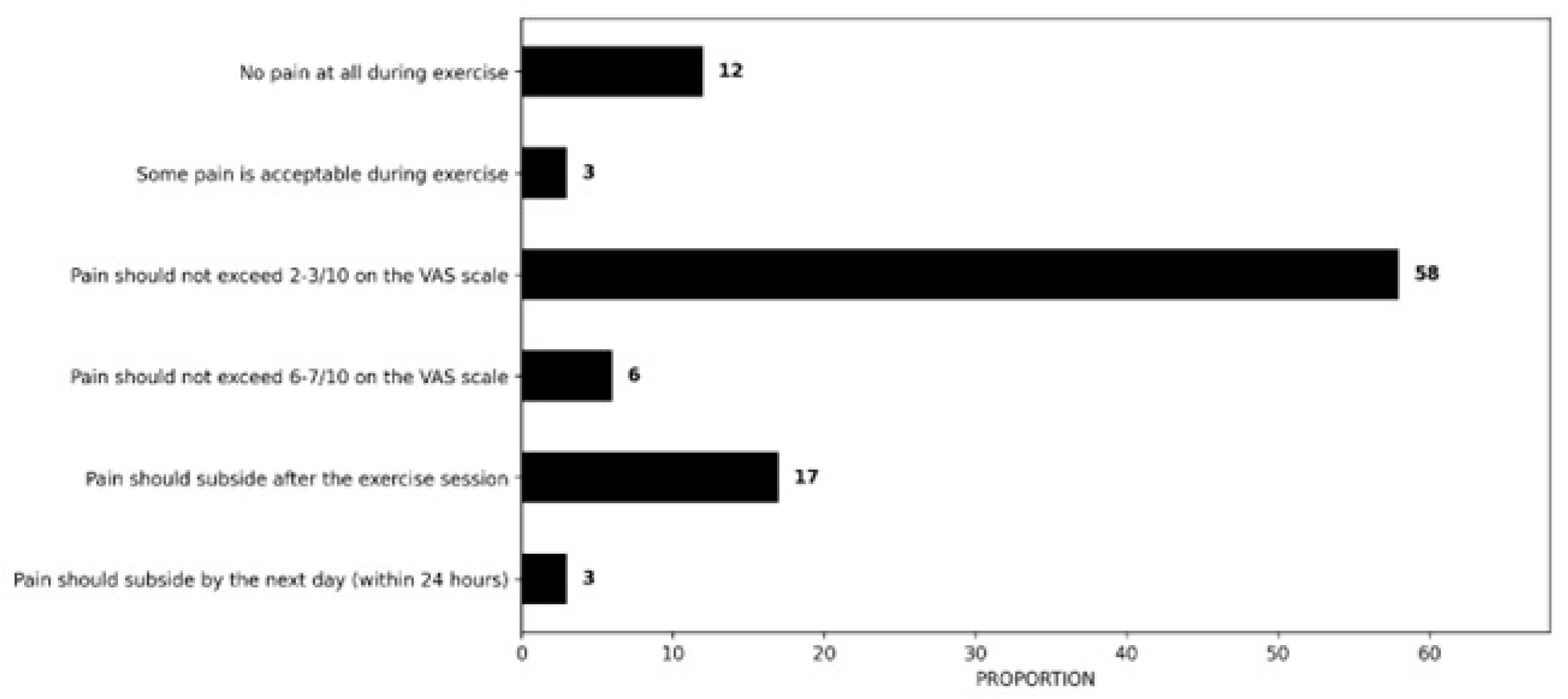

Patient symptoms were the primary factor influencing decisions to consider or adjust exercise parameters. Pain was consistently a major factor in determining exercise parameters. However, the specific symptom thresholds used to guide these decisions varied considerably. Most respondents (58%, n = 83/143), when explaining, identified pain scale values of up to 2–3/10 as acceptable, while 17% (n = 24/143) reported pain should subside after the exercise session. This is consistent with research suggesting that moderate pain levels, up to 5/10, may offer potential benefits compared to pain-free exercise in the management of RCRSP [

80]. Additionally, a consensus study suggests that experiencing mild to moderate pain (NRS/VAS ≤ 4/10) during exercise is acceptable as long as it returns to baseline levels within 12 h [

81]. However, some experts argue that exercise should not trigger patient-specific pain [

39]. A systematic review and meta-analysis on chronic musculoskeletal pain found that “painful” exercise provided significant short-term benefits compared to “pain-free” exercise [

82]. The potential effects of exercising with pain have been partly attributed to the modulation of the nociceptive-inhibitory system. Additionally, it has been suggested that exercising at higher loads, often associated with increased pain, may promote greater tissue adaptation and accelerate recovery [

83].

Recommendations regarding exercise parameters varied considerably, highlighting again the heterogeneity of exercise protocols in the literature [

26,

78]. There was notable variation in recommendations related to exercise load, sets, repetitions, and frequency. Most respondents (43%, n = 61/143) reported determining load intensity based on patient symptoms (e.g., selecting a load that does not provoke pain exceeding 4–5/10 on the VAS scale), while 29% (n = 42/143) preferred starting with a low load (e.g., a 1–2 kg dumbbell). The majority of respondents (77%, n = 110/143) suggested that sets and repetitions should be adjusted according to the patient’s symptoms and irritability. Regarding exercise frequency, most physiotherapists recommended either daily exercise (31%, n = 45/143) or tailoring the frequency based on the patient’s symptoms (30%, n = 43/143). Overall, physiotherapists consistently highlighted the importance of progressively increasing exercise difficulty by modifying load or other dosage parameters, such as sets and repetitions. This approach aligns with current evidence and clinical guidelines [

16,

25].

4.4. Treatment Timeline

Almost all physiotherapists would recommend seeing patients with RCRSP either weekly (62%, n = 88/143) or fortnightly (30%, n = 43/143) to review or adjust exercises. A frequency of one therapy session per week was also frequently recommended in France (70%) [

37], Australia (49.8%) [

36] and Greece (55%) [

39], consistent with expert consensus [

83].

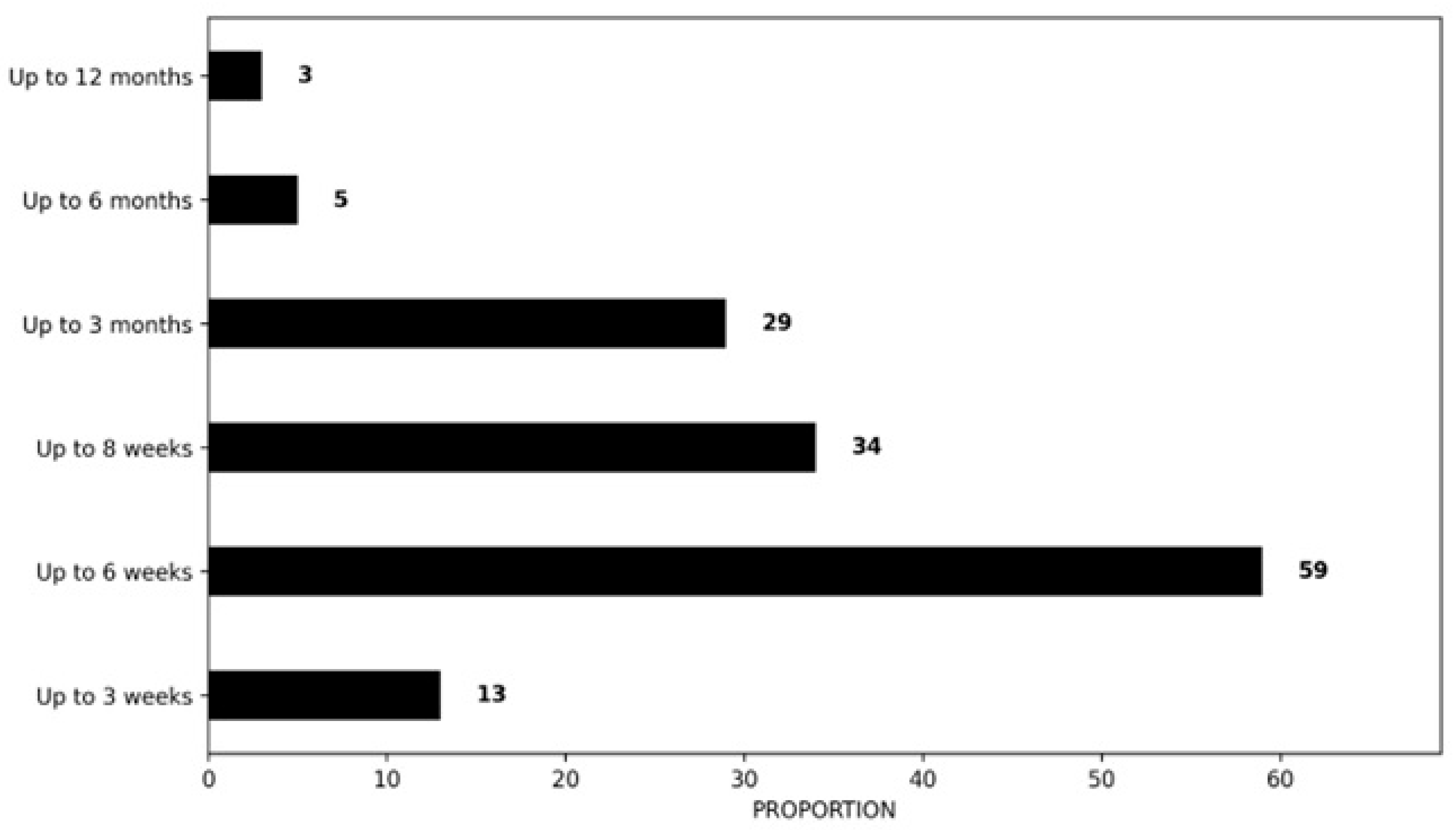

Regarding treatment frequency, 41% (n = 59/143) of the respondents would expect to treat RCRSP patients for 6 months or longer, whereas 24% (n = 34/143) would expect a treatment period of up to 8 weeks, results similar to those of Greek physiotherapists, which contradict the current guidelines that exercise programs should be undertaken for at least 12 weeks [

16,

25,

27,

46]. This diversity was also observed in the comparative countries [

33,

35,

36,

37,

39]. Findings from France suggested that 84.0% of respondents would expect to see a RCRSP patient for up to 12 weeks of treatment, 60.2% in Australia, 50% in the United Kingdom, 38.8% in Belgium/the Netherlands, and 12% in Greece.

The need for further investigation into the dosage parameters for exercise management in RCRSP and the clinical reasoning physiotherapists employ when prescribing exercise is evident. As previously noted, the existing literature demonstrates significant variability in specific exercise prescriptions, as indicated by the findings of this study. Furthermore, the absence of a unified approach to exercise treatment for RCRSP may be attributed to the diverse clinical presentations of pain and dysfunction, which necessitate an individualised adjustment to exercise management. In this context, clinical reasoning plays a crucial role, enabling physiotherapists to effectively customise treatment strategies to meet each patient’s unique needs, thereby enhancing therapeutic outcomes [

84,

85].

4.5. Adjunctive Treatment

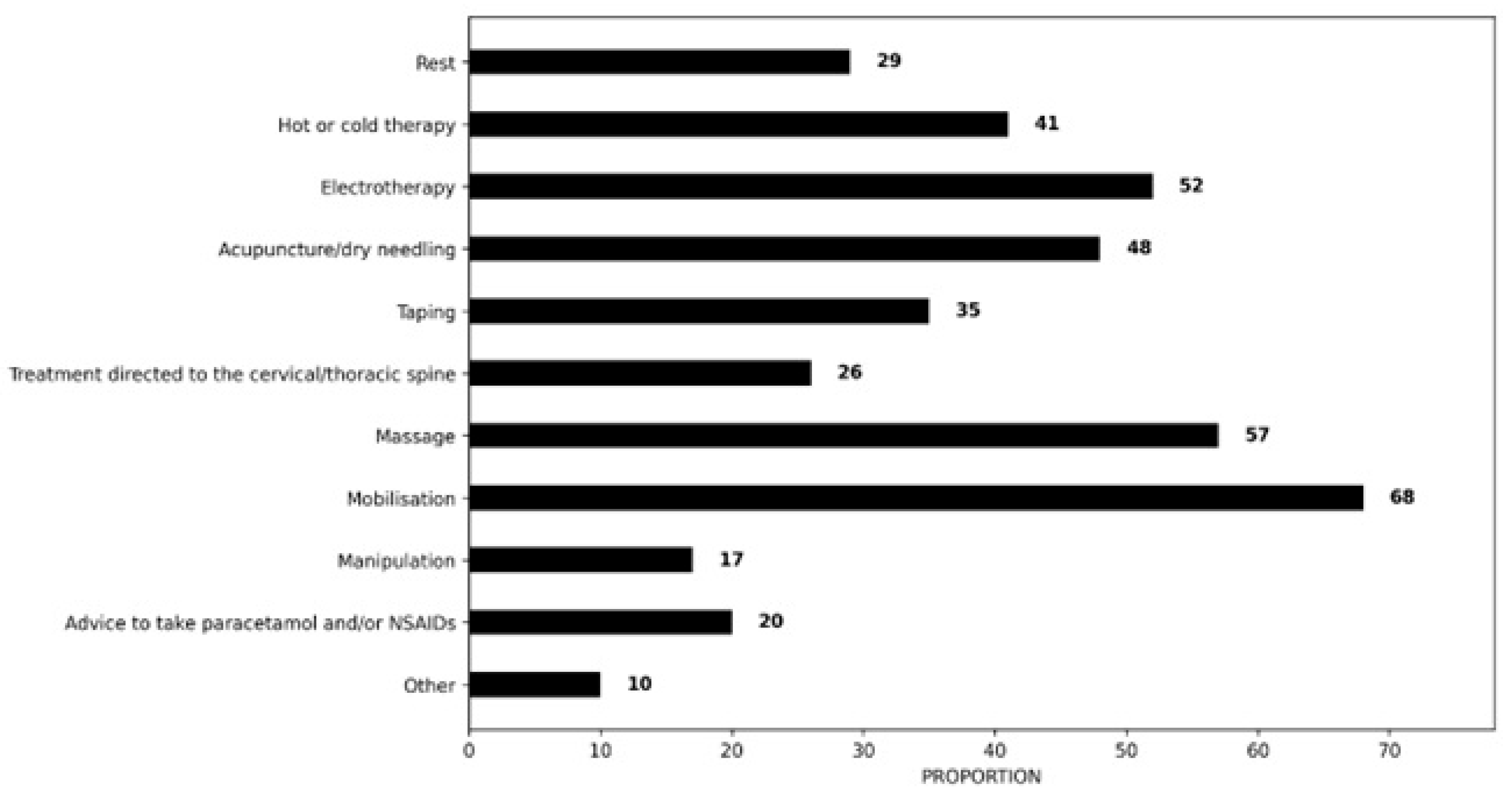

In addition to education and exercise therapy, respondents selected a range of treatment methods, varying in type and frequency. Most physiotherapists would provide some form of manual therapy [mobilisation (68%, n = 97/143)] based on the clinical scenario. This is consistent with guideline recommendations demonstrating short-term effects for manual therapy in combination with active exercise therapy in terms of pain reduction [

16,

18,

25]. The findings are comparable to those of French (70%), Australian (62%) and Greek (67%) physiotherapists [

36,

37,

39]. However, it is important to note that more recent research has raised concerns about the clinical relevance of incorporating manual therapy techniques in the management of RCRSP [

86,

87]. Recent evidence also suggests that cervical or thoracic spinal joint manipulation does not improve short-term pain intensity or function in persons with painful shoulder [

88].

The findings of this survey highlight the use of adjunctive treatment interventions with limited (electrotherapy) or inconclusive (acupuncture, taping, massage) clinical value [

24,

25,

26]. Despite evidence indicating that massage and electrotherapy provide no therapeutic benefit in the management of RCRSP, a considerable proportion of Cypriot physiotherapists reported their use in response to the clinical vignette (57%, n= 81/143 and 52%, n = 74/143, respectively), a pattern comparable to Greek physiotherapists (58% and 56%, respectively). This contrasts markedly with lower usage rates of electrotherapy observed among Australian (11.2%), French (12.1%), Belgian/Dutch (4%), and British (1%) physiotherapists [

33,

35,

36,

37], suggesting potential variability in clinical practice patterns across different healthcare contexts. Furthermore, the consequences of employing ineffective treatment modalities extend beyond simple inefficiency; they may significantly compromise the effectiveness of conservative management approaches, contribute to prolonged symptoms, and elevate the risk of patients requiring more invasive interventions, including imaging, injections, or surgical procedures, but also a cost-efficacy issue using ineffective treatments. This is particularly concerning in the context of shoulder pain management, where clinical decision-making should be firmly grounded in evidence-based practices that optimise patient outcomes while ensuring the judicious use of healthcare resources [

24,

25,

26].

4.6. Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. Firstly, using convenience sampling introduces a risk of sampling bias [

89]. Invitation to survey participation was through social media platforms, e-mail distribution lists and physiotherapy associations. This approach likely excludes physiotherapists who are less active on these platforms and will not have had the opportunity to respond. Due to how the survey was distributed, it is impossible to determine how many individuals viewed the advertisement versus those who completed it. Therefore, the findings may not accurately reflect the broader population of physiotherapists in Cyprus. Additionally, the reliance on self-reported data introduces the potential for response bias, where participants may provide answers influenced by social desirability or personal beliefs, potentially influencing the results [

90]. Furthermore, the total number of respondents (n = 143), although lower than in similar studies conducted in larger countries, represents approximately 11% of all registered physiotherapists in Cyprus. Considering the smaller size of the national workforce, the sample may still offer a reasonably representative snapshot of current clinical practice. Additionally, the relatively small sample size, along with the limited expertise (36% of respondents) and experience (40% with ≤5 years of practice) among a significant portion of participants, may further constrain the robustness and applicability of the study’s conclusions.

Another significant limitation is the survey methodology. The online survey was developed using a translated and adapted questionnaire based on existing literature; however, its reliability and validity have not yet been evaluated. The language and cultural adaptation of the survey instrument pose additional limitations. While the questionnaire was translated into Greek and modified to suit the local context, the adequacy of the translation process and the effectiveness of the cultural adaptation are not fully assured, raising concerns about potential misinterpretations or cultural biases. Additionally, the Greek-translated version of the questionnaire did not undergo formal reliability testing (e.g., internal consistency or test–retest analysis), which should be considered when interpreting the findings.

Evidence indicates that vignette studies are valid, reliable, cost-effective, and practical for investigating clinical practice [

42,

91,

92]. Vignette-based study designs offer valuable insights into clinical decision-making processes, facilitating the evaluation of care quality and adherence to guideline standards in a structured, reproducible manner [

91]. Careful development of the case vignette, grounded in current research evidence, helps minimise the risk of bias [

93]. Additionally, this vignette has undergone continuous updates, adaptations, and multiple pilot tests as part of international comparative studies [

91]. The depiction of a typical patient presenting with symptoms and functional impairments related to rotator cuff pathology was adapted from Smythe et al. [

36] and translated into Greek [

39].